Abstract

Non-monetary rewards are frequently used to promote pro-social behaviors, and these behaviors often result in approval from one’s peers. Nevertheless, we know little about how peer-approval, and particularly competition for peer-approval, influences people’s decisions to cooperate. This paper provides experimental evidence suggesting that people in peer-approval competitions value social approval more when it leads to unique and durable rewards. Our evidence suggests that such rewards act as a signaling mechanism, thereby contributing to the value of approval. We show that this signaling mechanism generates cooperation at least as effectively as cash rewards. Our findings point to the potential value of develo** new mechanisms that rely on small non-monetary rewards to promote generosity in groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Ellingsen and Johannesson (2007) documented work that relates to how non-monetary incentives (e.g., respect) influence worker productivity.

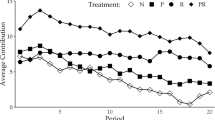

Pan and Houser (2011) report three of the seven treatments reported in this paper (new to this paper are the “Star”, “Competition-only,” “Cash” and “Control” treatments). The earlier paper connects the patterns in our data to theories in evolutionary psychology, with an emphasis on gender effects. The present paper pursues a very different approach, analyzing and interpreting aggregate data patterns through the lens of economic theory. Loosely speaking, the first paper is interested in identifying specifically who did and who did not respond to specific treatment contexts. It then develops an explanation for why. The present paper, in contrast, attempts to explain aggregate behavior using economic theory that might generalize across contexts in a way that informs the design of institutions to promote pro-sociality.

For simplicity, we refer to a participant as “he”.

For example, a player who receives the most approval points for three periods will see three gold stars displayed on their screen at the end of that period.

Also referred to as “image motives,” the idea is that an individual’s behavior can be directed by a desire to create a good impression in the eyes of others. Signaling motives have been invoked to explain a number of pro-social behaviors, including why charities advertise their donors’ names (Harbaugh 1998), why football teams place highly visible emblems on the helmets of high performers (Wired 2011), and why top employees are rewarded with prizes, e.g., gold cups for employees of the month.

Note that Holländer’s model cannot make predictions regarding the relationship between contributions and the approval rate in either the No-competition or Control treatments, because the environments are different.

Kumru and Vesterlund (2008) found the important role of status on voluntary contribution. Low status followers are likely to mimic contributions by high-status leaders; in turn, this encourages high-status leaders to contribute.

Note Holländer does not refer to these curves as Supply and Demand. We do so because they share features of supply and demand curves relevant for our purposes. Appendix 2 details the formation of these curves.

If more than one player in a group earned the most approval, we display the highest contribution among these winners.

All sessions were run in summer, with temperatures approaching eighty degrees Fahrenheit.

We invited another 30 students to participate in the Willingness-to-pay (WTP) elicitation game based on the Becker–DeGroot–Marschak (1964) random auction mechanism. We elicited values for the mug as well as the Haagen-Dazs ice cream bar (see Fig. 5 in Appendix 1). We found participants to have statistically insignificantly different WTP for the mug and the ice cream (mug vs. ice cream: $2.20 vs. $1.70, n = 30, p = 0.81).

We chose a cash value equal to $3, which is higher but marginally significantly different from the elicited point estimate of the value of the mug (p = 0.08, two-sided t test). The higher cash value works against our hypothesis of the dominance of mug rewards over cash.

There are two assumptions underlying this. One is that rewards with a greater number of these three (independent) features are more desirable than rewards with fewer. The other is that people compete more for more desirable rewards.

The number of observations reported in Results 1, 2 and 3 correspond to number of groups. In Result 4, where we compare among cooperators and among free-riders, the number of observations is number of individuals.

Unless otherwise noted, all p-values derive from two-sided Mann–Whitney tests.

We categorized this way due to the pattern of individual contributions: 83.6 % of all contribution decisions are at exactly 0, 5, 10, 15 or 20 (with 23 % at 0, 9 % at 5, 11 % at 10, 8 % at 15 and 33 % at 20).

Note that there is no approval assignment stage in the Control treatment. The No-competition treatment has approval, but no competition for approval.

Whether the No-competition treatment is included in this analysis does not affect the level of significance (p < 0.001, two-sided t test, n = 62 groups).

Note that Control is not reported here because it does not include approval points. However, contributions by cooperators in Control were significantly lower than in Mug (mean = 8.5 in Control, p < 0.01). The same results hold for free-riders when comparing between the two treatments (mean = 4.2 in Control, p < 0.01).

We also checked for the presence of anti-social approval patterns. In order to examine this, we created a group-level dummy variable which takes value 1 in a period if, in that period, the person who received the most approval also contributed the most in that group; and equals 0 otherwise. This gives 10 observations per group over ten periods, and by averaging over all groups and periods we found the overall frequency, for each treatment, that the person who received a highest approval also contributed the most. For all treatments, the frequency is 90 % or higher. Further, there are no significant differences in frequencies between these treatments and the No-Competition treatment where subjects have not been provided with any comparative information among group members.

Assume that individual contribution is negligible in calculating the society’s average contribution.

“We generally approve of cooperative behavior even if it does not make us significantly better off. In doing so, we often seem to consider the hypothetical advantage we would enjoy if everybody else behaved cooperatively in like manner. This motivates the assumption that an agent’s approval rate, his subjective value of another agent’s marginal contribution stimulating approval, is equal to the hypothetical advantage, measured in terms of the private good, that the former agent would enjoy if not only the latter but also all other agents except him increased their contributions marginally. (Holländer 1990).

References

Andrenoi, J., & Petrie, R. (2004). Public goods experiments without confidentiality: A glimpse into fund-raising. Journal of Public Economics, 88, 1605–1623.

Andreoni, J. (1995). Cooperation in public-goods experiments: Kindness or confusion? The American Economic Review, 85(4), 891–904.

Andreoni, J., & Bernheim, D. (2009). Social image and the 50–50 norm: A theoretical and experimental analysis of audience effects. Econometrica, 77(5), 1607–1636.

Andreoni, J., Harbaugh, W., & Vesterlund, L. (2003). The carrot or the stick: Rewards, punishments, and cooperation. American Economic Review, 93(3), 893–902.

Ariely, D., Bracha, A., & Meier, S. (2009). Doing good or doing well? Image motivation and monetary incentives in behaving prosocially. American Economic Review, 99(1), 544–555.

Bénabou, R., & Tirole, J. (2006). Incentives and pro-social behavior. American Economic Review, 96(5), 1652–1678.

Bochet, O., Page, T., & Putterman, L. (2006). Communication and punishment in voluntary contribution experiments. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 60(1), 11–26.

Charness, G., Masclet, D. and Villeval M.C. (2010) Competitive Preferences and Status as an Incentive: Experimental Evidence. IZA Discussion Paper 5034.

Chen, Y., Happer, M., Konstan, J., & Li, S. (2010). Social comparisons and contributions to online communities: A field experiment on movie lens. American Economic Review, 100, 1358–1398.

Denant-Boemont, L., Masclet, D., & Noussair, C. (2007). Punishment, counter punishment and Sanction Enforcement in a social dilemma environment, symposium on behavioral game theory. Economic Theory, 33, 154–167.

Dreber, A., Rand, D. G., Fudenberge, D., & Nowak, M. A. (2008). Winners don’t punish. Nature, 452, 348–351.

Duffy, J., & Kornienko, T. (2010). Does competition affect giving? Journal of Economic Behavior Organization, 74, 82–103.

Dugar, S. (2010). Non-monetary sanction and behavior in an experimental coordination game (2010). Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 73(3), 377–386.

Dugar, S. (2013). Non-monetary incentives and opportunistic behavior: Evidence from a laboratory public good game. Economic Inquiry, 51(2), 1374–1388.

Ellingsen, T., & Johannesson, M. (2007). Paying respect. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(4), 135–149.

Ellingsen, T., & Johannesson, M. (2011). Conspicuous generosity. Journal of Public Economics, 95(9–10), 1131–1143.

Eriksson, T., & Villeval, M. C. (2012). Respect and relational contracts. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 81, 286–298.

Fehr, E., & Gächter, S. (2000). Cooperation and punishment in public goods experiments. American Economic Review, 90, 980–994.

Fischbacher, U. (2007). z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Experimental Economics, 10, 171–178.

Fuster, A., & Meier, S. (2010). Another hidden cost of incentives: The detrimental effect on norm enforcement. Management Science, 56(1), 57–70.

Harbaugh, W. (1998). The prestige motive for making charitable transfers. American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings of the Hundred and Tenth Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association, 88(2), 277–282.

Herrmann, B., Thoni, C., & Gachter, S. (2008). Antisocial punishment across societies. Science, 319(5868), 1362–1367.

Holländer, H. (1990). A social exchange approach to voluntary cooperation. American Economic Review, 80(5), 1157–1167.

Kandel, E., & Lazear, E. P. (1992). Peer pressure and partnerships. Journal of Political Economy, 100(4), 801–817.

Kosfeld, M., & Neckermann, S. (2011). Getting more work for nothing? Symbolic awards and worker performance. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 3, 86–99.

Kumru, C., & Vesterlund, L. (2008). The effects of status on voluntary contribution. Journal of Public Economic Theory, 12(4), 709–778.

Lacetera, N., & Macis, M. (2010). Do all material incentives for pro-social activities backfire? The response to cash and non-cash incentives for blood donations. Journal of Economic Psychology, 31, 738–748.

Li, L., & **ao, E. (2014). Money talks? An experimental study of rebate in reputation system design. Management Science, 60, 2054–2072.

Mas, A., & Moretti, E. (2009). Peers at work. American Economic Review, 99(1), 112–145.

Masclet, D., Noussair, C., Tucker, S., & Villeval, M. C. (2003). Monetary and nonmonetary punishment in the voluntary contributions mechanism. American Economic Review, 93(1), 366–380.

Neckermann, S., Cueni, R., & Frey, B. (2014). Awards at work. Labour Economics, 31, 205–217.

Noussair, C., & Tucker, S. (2005). Combining monetary and social sanctions to promote cooperation. Economic Inquiry, 43(3), 649–660.

Pan, X. S., & Houser, D. (2011). Competition for trophies triggers male generosity. PLoS ONE, 6(4), e18050.

Rand, D. G., Dreber, A., Ellingsen, T., Fudenberg, D., & Nowak, M. A. (2009). Positive interactions promote public cooperation. Science, 325, 1272–1275.

Sefton, M., Shupp, R., & Walker, J. M. (2007). The effect of rewards and sanctions in provision of public goods. Economic Inquiry, 45(4), 671–690.

Stoop, J., Soest, D., Vyrastekova, J. (2011) Carrots without bite: On the ineffectiveness of ‘rewards’ in sustaining cooperation in social dilemmas. MPRA working paper 30538.

Visser, M. S., & Roelofs, M. (2011). Heterogeneous preferences for altruism: Gender and personality, social status, giving and taking. Experimental Economics, 14, 490–506.

Acknowledgments

We thank Omar Al-Ubaydli, David Eil, Ragan Petrie and seminar participants at George Mason University, University of Birmingham, University of East Anglia and University of St. Lawrence, University of Texas at Dallas, University of the Andes (Bogota) and the ESA American conference for helpful comments and discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendices

Appendices

1.1 Appendix 1

See Fig. 5.

1.2 Appendix 2: The framework of Holländer (1990)

An individual receives utility from private consumption, public goods, and social approval. As a result, an individual must make decisions regarding private consumption, contribution to the public good and amount of approval to dispense to others. In making these decisions, a typical agent is confronted with the respective behaviour of others, characterized by \( w \), the approval for each unit of contribution (i.e., the unit approval rate) and \( \bar{g} \), the average contribution of the society.Footnote 25 An individual responds to others’ behaviour by some rationally chosen contribution \( g_{i} \), and what Holländer refers to as an “emotionally” determined approval rate, \( v \), which he applies to others’ contributions. These are the key quantities underlying the hypotheses in the current paper, and the following two sub-sections explain how these two variables are determined in Holländer’s (1990) model.

1.2.1 Individual contribution \( g_{i} \)

Given that the unit approval rate of others is \( w \), the absolute contribution of the individual is \( g_{i} , \) the approval assigned due to absolute contribution is \( wg_{i} \), and approval assigned due to his contribution relative to the average contribution is \( w*\left( {g_{i} - \bar{g}} \right) \). If we assume that the overall approval assigned to any individual i is a weighted average of approval assigned due to an individual’s absolute contribution level (weight \( 1 - \beta ) \) and approval assigned due to an individual’s contribution relative to the average contribution (weight \( \beta ) \). we have

Approval assigned to individual \( i \)

Note that if one contributes the same as the average contribution \( \bar{g} \), the approval assigned to him is:

Holländer’s key departure from the traditional public goods literature is that he assumes people value receiving social approval. Intuitively, we not only want to receive approbation, but also care about how much approbation we receive in comparison to others. Therefore, assume that utility from approval received is determined by both the approval received by individual \( i \), that is, Eq. (1) (weight \( (1 - \alpha ) \)), and how much he receives relative to that received by the group average contribution, that is, \( w(g_{i} - \bar{g})w*\left( {g_{i} - \beta \bar{g}} \right) - \left( {1 - \beta } \right)w\bar{g} = w*(g_{i} - \bar{g}) \) (weight \( \alpha \)). Therefore, the total utility from received approval for individual \( i \) is:

Let \( \sigma = \alpha + \beta - \alpha \beta \), so that we have utility from received approval for individual i to be equal to:

Note that \( \sigma \) increases with both \( \alpha \) and \( \beta \). \( \beta \) is a weight parameter that captures how competition influences approval assignment while \( \alpha \) captures the role of competition on the way approval is valued. An increasing \( \beta \) indicates that approval assigned to a typical individual is based more on how much he contributes relative to the group average; an increasing \( \alpha \) captures how much a typical individual cares about the relative approval received. Intuitively, a more competitive environment will increase \( \alpha \) and \( \beta \) and thus increase \( \sigma \).

An individual’s total utility is characterized by additively separable preferences between private consumption, public goods, and approval received. Thus, the utility function for individual \( i \) is:

Taking the f.o.c. condition of \( U_{i} \) with respect to \( g_{i} \), we find:

We focus exclusively on symmetric equilibria, where an individual’s contribution is equal to the average contribution so that \( g_{i} = \bar{g} \). Substituting this equality into Eq. (5), we have \( U_{p}^{{\prime }} \left( {\pi - \bar{g}} \right) = wU_{A}^{{\prime }} [w*(\bar{g} - \sigma \bar{g})] \), so that,

As noted, this is referred as the \( g_{i} \bar{g} \) equilibrium in Holländer (1990).

Assuming all utility functions are concave, an increase in \( \bar{g} \) leads to an increased ratio \( \frac{{U_{p}^{{\prime }} \left( {\pi - \bar{g}} \right)}}{{U_{A}^{{\prime }} [w*\bar{g}(1 - \sigma )]}} \). That is, the \( g\bar{g} \) curve is an upward slo** curve, with approval rate w increasing with the average contribution \( \bar{g} \). This curve is referred as the supply curve in the main text.

1.2.2 The approval rate \( v \)

The approval rate is determined by the marginal rate of substitution between public goods and private consumption. Intuitively, the higher the pleasure one derives from contributions to the public goods relative to that of private consumption, the higher the approval rate should be, and vice versa.Footnote 26

In equilibrium, the individual approval rate must be equal to the approval rate of others, \( v = w \). Given (5), we know that \( \sigma wU_{A}^{{\prime }} [w*(g_{i} - \sigma \bar{g})] = \sigma U_{p}^{{\prime }} \left( {\pi - g_{i} } \right) \). Substituting this and \( v = w \) together into (7), we obtain \( w = \frac{{U^{{\prime }}_{g} \left( {\bar{g}} \right) - \sigma U_{p}^{{\prime }} \left( {\pi - g_{i} } \right)}}{{U_{p}^{{\prime }} \left( {\pi - g_{i} } \right)}} \), or

Equation (8) is referred as the VW equilibrium in Holländer’s paper. It occurs when the individual approval rate is equal to others’ approval rates. This is the structure of the demand curve. We characterize the demand curve in social exchange equilibrium below. See the discussion surrounding Proposition 1.

1.2.3 Social exchange equilibrium

Holländer (1990) denotes the simultaneous \( VW \) and \( g\bar{g} \) equilibrium as a social equilibrium. Substituting \( g_{i} = \bar{g} \) into (8), we have

Proposition 1

An increase in the competitiveness of the environment (\( \sigma \)) leads to a downward shift of the \( VW \) curve.

Assuming the utility function to be concave, based on Eq. (9), an increase in \( \bar{g} \) leads to a decrease in the ratio of \( \frac{{U_{{\bar{G}}}^{{\prime }} \left( {\bar{g}} \right)}}{{U_{p}^{{\prime }} (\pi - \bar{g})}} \), and thus the \( VW \) curve is negatively sloped. This is the demand curve mentioned in the manuscript. Meanwhile, an exogenous increase in the competitiveness of the environment \( \sigma \) leads to a downward shift of the \( VW \) curve (see movement (1) in Fig. 6 below).

The approval rate \( w \) is on the vertical axis and the average contribution \( \bar{g} \) on the horizontal axis. The solid black curve is the VW cruve, also referred as the demand curve in the main text. The solid grey curve is the \( g\bar{g} \) curve, also referred as supply curve in the main text. The black dashed line shows a downward shift of the VW curve [movement (1)] after an increase in the competitiveness of the environment. The dashed grey line shows a downward shift of the \( g\bar{g} \) curve after an increase in the competitiveness of the environment. The equilibrium changes from \( e_{1}^{*} \) to \( e_{2}^{*} \). We can see that the overall effect is a decreased approval rate w, and an ambiguous change in equilibrium contribution level

For the \( g\bar{g} \) equilibrium, we had Eq. (6) as:

Proposition 2

An increase in competitiveness of the environment \( \sigma \) shifts down the \( g\bar{g} \) curve, which is referred as the supply curve in the main text. In particular, observe that the \( g\bar{g} \) curve is influenced by two variables: the endowment \( \pi \) and the competitiveness of the environment \( \sigma \). An increase in \( \sigma \) leads to a decreased ratio of \( \frac{{U_{p}^{{\prime }} \left( {\pi - \bar{g}} \right)}}{{U_{A}^{{\prime }} [w*\bar{g}(1 - \sigma )]}} \), thus a downward shift of the \( g\bar{g} \) curve (see movement (2) in Fig. 6 below).

Proposition 3

When \( \sigma < \frac{{U_{{\bar{G}}}^{{\prime }} \left( 0 \right)}}{{U_{p}^{{\prime }} (\pi )}} - \frac{{U_{p}^{{\prime }} \left( \pi \right)}}{{U_{A}^{{\prime }} (0)}} \), there exists a unique social equilibrium with positive \( w^{*} \) and \( \bar{g}^{*} \).

The intersection of the \( VW \) curve with the vertical axis occurs where \( \bar{g} = 0 \). Substituting this into in (9), we have: \( w = \frac{{U_{{\bar{G}}}^{{\prime }} \left( 0 \right)}}{{U_{p}^{{\prime }} (\pi )}} - \sigma \). The intersection of the \( g\bar{g} \) curve with the vertical axis occurs where \( \bar{g} = 0 \), and substituting this into (6) we have \( w = \frac{{U_{p}^{{\prime }} \left( \pi \right)}}{{U_{A}^{{\prime }} (0)}} \). Thus, if \( \frac{{U_{{\bar{G}}}^{{\prime }} \left( 0 \right)}}{{U_{p}^{{\prime }} (\pi )}} - \sigma > \frac{{U_{p}^{{\prime }} \left( \pi \right)}}{{U_{A}^{{\prime }} (0)}} \), that is, \( 0 < \sigma < \frac{{U_{{\bar{G}}}^{{\prime }} \left( 0 \right)}}{{U_{p}^{{\prime }} (\pi )}} - \frac{{U_{p}^{{\prime }} \left( \pi \right)}}{{U_{A}^{{\prime }} (0)}} \), then there exists a unique social equilibrium with positive \( w^{*} \) and \( \bar{g}^{*} \).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pan, X., Houser, D. Social approval, competition and cooperation. Exp Econ 20, 309–332 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-016-9485-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-016-9485-0