Abstract

Purpose

Biallelic mutations in the CEP290 gene cause early onset retinal dystrophy or syndromic disease such as Senior-Loken or Joubert syndrome. Here, we present an unusual non-syndromic case of a juvenile retinal dystrophy caused by biallelic CEP290 mutations imitating initially the phenotype of achromatopsia or slowly progressing cone dystrophy.

Methods

We present 13 years of follow-up of a female patient who presented first with symptoms and findings typical for achromatopsia. The patient underwent functional and morphologic examinations, including fundus autofluorescence imaging, spectral-domain optical coherence tomography, electroretinography, color vision and visual field testing.

Results

Diagnostic genetic testing via whole genome sequencing and virtual inherited retinal disease gene panel evaluation finally identified two compound heterozygous variants c.4452_4455del;p.(Lys1484Asnfs*4) and c.2414T > C;p.(Leu805Pro) in the CEP290 gene.

Conclusions

CEP290 mutation causes a wide variety of clinical phenotypes. The presented case shows a phenotype resembling achromatopsia or early onset slowly progressing cone dystrophy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Inherited retinal diseases (IRD) are a clinically and genetically heterogenous group of conditions with dysfunction and/or degeneration of cells of the retina. Since cilia are essential for many cell types including photoreceptors, there is a wide range of retinal phenotypes associated with mutations in genes affecting the photoreceptor connecting cilium. Resulting diseases are called ciliopathies [1]. One of the most intriguing ciliopathy-associated disease genes is the gene for Centrosomal Protein 290 (CEP290), in which mutations cause various distinct retinal phenotypes, ranging from non-syndromic Leber congenital amaurosis, early onset IRD or retinitis pigmentosa over Senior-Loken, Joubert, and Bardet-Biedl, to lethal Meckel-Grüber syndrome [1, 2]. The CEP290 gene encodes a protein involved in ciliary assembly and trafficking. It is expressed in photoreceptors, but also in multiple other tissues. Today, more than 100 CEP290 mutations have been described, but the phenotype–genotype correlation is not fully understood [1]. In photoreceptors, CEP290 localizes to the connecting cilium, the transitional zone linking the inner and outer segments of rods and cones [3]. The most typical presentation of CEP290 intraretinal disease seems to be Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA), followed by retinitis pigmentosa and cone–rod dystrophy [4]. The LCA is the earliest and most severe form of all inherited retinal dystrophies, causing profound visual deficiency, nystagmus, and an undetectable or severely reduced ERG in the first year of life. [1] Retinitis pigmentosa or severe cone–rod-type retinal dystrophy phenotypes caused by CEP290 lead usually to severe visual impairment. Visual field deteriorate relatively fast and electroretinograms are undetectable in the majority of the patients [4]. Early fundus changes include white dots or a marbleized or salt and pepper aspect and progress to midperipheral nummular or spicule pigmentation [5]. However, milder cases with almost normal visual acuity in adult age are known, too [4, 5],

A detailed study of the retinal architecture of human CEP290-mutant retinas identified profound retinal remodeling in the peripheral rod-rich regions and no clear alterations in the cone-rich foveal region. This difference in rod and cone degeneration may point to a distinct function of CEP290 in both cell types [6].

In this report, we present a patient with cone-dominated IRD carrying biallelic heterozygous variants in CEP290, showing characteristics of achromatopsia, thereby broadening the spectrum of CEP290-associated disease.

Case presentation

A female patient of Caucasian origin presented at the University Eye Hospital Tübingen, Germany at 6 months of age with nystagmus which persisted since birth. No other developmental abnormalities were observed.

Ophthalmologic examination showed pendulum-shaped, rotational and also dissociated nystagmus beating in all directions. Additionally, the patient showed frequent rubbing of the eyes, especially when tired. At the age of 2 years, she also developed increased glare sensitivity and slight anisocoria. Visual acuity was always poor, and retinoscopy showed bilateral age-related hyperopia of ~ 3 diopters at the age of 2 years. Later, the patient developed divergent strabism with left eye fixation. Funduscopy showed normal retina, the remaining morphology of the anterior eye segment did not show any pathologies.

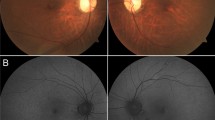

Multimodal diagnostics of the retina was performed at the age of 6 years. The best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was logMAR 1.6 on the right and 1.4 on the left eye. In the visual field (semiautomated kinetic perimetry), a slight concentric constriction and a central scotoma were seen; however, due to the young age, this could have been caused by reduced cooperation during perimetry, or by nystagmus. Photophobia persisted. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) showed macular layering with a slight diffuse atrophy of the outer segments (Fig. 1). Full-field electroretinography (ERG) at the age of 6 years showed normal scotopic responses, but abnormal shape of the oscillatory potentials and no reproducible photopic responses (Fig. 2). The Farnsworth test performed binocularly revealed color perception disorder along all three axes and anomaloscope examination suggested findings consistent with achromatopsia.

Despite repeated and extensive genetic analysis for mutations in upcoming known achromatopsia genes, no causative mutations were detected.

At the age of 14 years, the clinical findings did not reveal much progression (Fig. 1). Wide-field fundus autofluorescence performed at the age of 14 years showed a hypo- and hyperautofluorescent pattern (Fig. 1) not typical for achromatopsia.

Finally, IRD gene analysis out of whole genome sequencing data within a diagnostic genetic testing setup at the age of 14 years identified two heterozygous variants: c.4452_4455del;p.(Lys1484Asnfs*4) and c.2414T > C;p.(Leu805Pro) in CEP290 (ENST00000552810.1). Segregation analysis in both parents confirmed biallelic occurrence (Fig. 2).

Full-field electroretinography was performed at the age of 6 years and 14 years according to the ISCEV (international society for electrophysiology of vision) standards. Due to strong photophobia, some of the recordings are biased by lid and movement artifacts, but demonstrate a non-recordable light-adapted response at both visits and close-to-normal dark-adapted responses. The corresponding OCT images on the right show macular layering with a diffuse atrophy of the outer segments. The Fundus photographs and Autofluorescence of both eyes show central thinning of the retina which presents as a lighter appearance of the central part of the retina. DA, dark-adapted; LA, light-adapted; traces in red, right eye; traces in blue, left eye; green areas, age-adapted norm values

The variant c.4452_4455del;p.(Lys1484Asnfs*4) has already been associated with CEP290-associated phenotypes [2, 7, 8]. It results in frame shift and a truncated protein; the transcript is predicted to undergo nonsense mediated decay. It is classified as pathogenic. The variant c.2414T > C;p.(Leu805Pro) has also been reported in the literature and ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/866922/) is also associated with CEP290-related diseases [2]. This missense variant affects an evolutionary highly conserved amino acid residue in the coiled-coil domain CC IV of the SMC (structural maintenance of chromosome) homology domain of CEP290 [9]. Yet, prediction software ratings are inconsistent and classify this variant as variant of uncertain significance.

In the pedigree, no further family members were affected with a CEP290 phenotype or other type of inherited retinal degeneration.

Discussion

CEP290 mutations are associated with autosomal recessively inherited early childhood IRDs. Typically, the CEP290-related phenotype presents an early onset retinal dystrophy or LCA, or a severe cone–rod-type retinal dystrophy [4]. The CEP290 phenotype covers approximately 30% of patients with the typical LCA, whereas the most common variant is the deep intronic mutation c.2991 + 1665 [4]. In most of the cases, the CEP290 phenotype is characterized by an early onset of problems associated with rod and cone dysfunction, such as nystagmus, night blindness, visual field defect and reduced vision with a relatively rapid progression [4]. Still, cases of a typical retinitis pigmentosa with later onset and slower progression have been reported, too [4, 5]. The phenotype spectrum of CEP290 related retinal dystrophies is rather broad and includes also syndromic diseases such as Senior-Loken syndrome, Joubert syndrome, Bardet-Biedl syndrome or Meckel-Grüber syndrome [1, 2]. De Baere et al. described over 100 different mutations in CEP290 [1]. Resulting phenotypes are variable and can involve single or multiple organs. For the majority of mutations, no clear-cut genotype–phenotype correlation could be established.

Here, we describe an atypical case of a slowly progressing cone dystrophy caused by biallelic CEP290 variants, initially diagnosed as achromatopsia. Such a phenotype with early onset of visual impairment with nystagmus and photophobia demonstrating cone dysfunction from early age on; however, very slow progression up to the age of 14 years has not been published in the spectrum of CEP290 phenotypes to our knowledge yet. Due to this clinical presentation of barely progression cone dysfunction, the case was initially held for achromatopsia.

Achromatopsia is an inherited retinal disease with absent cone function resulting in congenital nystagmus, low vision, photophobia and inability to distinguish colors [10,11,12]. Patients with incomplete achromatopsia have a remaining cone function and present usually with milder symptoms. In its clinical presentation, it is mostly a stationary disease, but due to modern high-resolution imaging such as OCT, we know that there are progressive degenerative changes of cones in achromatopsia [13,14,15]. The initial presentation of achromatopsia is usually in the first month after birth with a life-long reduced visual acuity around 20/200 in the case of complete achromatopsia. In electroretinography, the cone signals are undetectable, or reduced in some cases of incomplete achromatopsia [13]. Based on clinical presentation, also other very slowly progressing cone dystrophies can be held for achromatopsia [16].

In our patient, the CEP290 variants lead to an early onset nystagmus, photophobia and low vision, along with unremarkable funduscopy, which clinically at first seemed consistent with achromatopsia. Additionally, during the first years, no clear progression could be documented. Moreover, the full-field electroretinography at the age of 6 showed undetectable cone responses with normal rod responses, which additionally supported the diagnosis of achromatopsia. Later, the diagnosis was corrected to cone dystrophy, especially based on the atypical fundus autofluorescence pattern that did not match to retinal imaging known for achromatopsia. Usually, patients with achromatopsia present with a normal or almost normal fundus autofluorescence with minimal foveal and perifoveal changes, thus such an autofluorescence pattern as in this case would be atypical for achromats [13].

Finally, by means of a genome sequencing, it could be shown that the case is a CEP290 phenotype, probably a cone dystrophy with a very slow progression.

Complete loss of function of both CEP290 alleles typically leads to Joubert syndrome, whereas patients with Leber congenital amaurosis and early onset IRD are expected to have a small amount of residual CEP290 activity [9].

CEP290-related IRD typically presents with congenital nystagmus or roving eye movements and hyperopia [6]. Both were also observed in our patient. Also, the severely reduced but not progressing loss of BCVA was reported earlier [17].

Swaroop et al. also described retinas of blind CEP290-related IRD patients did not show central degeneration and thinning [6]. This resembles our patients’ findings with only slight changes in the outer retinal layers and severe BCVA impairment despite normal central retinal structure. The central retina of the CEP290 phenotypes shows slowly progressive degeneration [6, 17]. In particular, the ellipsoid zone band width declined at a mean rate of about −2%/year [17]. However, these progression signs were not present in the first 14 years of our patient.

Also, Michaelides et al. previously described younger subjects are more likely to have a normal fundus, while older patients commonly showed evidence of peripheral retinal pigment migration [17, 18]. In addition, in our case, there is a discrepancy of well recordable scotopic ERG and a non-recordable photopic ERG in combination with a non-progressive IRD misleading the clinical diagnosis initially to achromatopsia, while typically CEP290-related IRD is associate with impaired or undetectable rod and cone responses [17].

The presented case expands the known spectrum of CPE290 related retinal disease. Long-term observation of this young patient is necessary to understand unusual genotype–phenotype correlations.

Conclusions

We present a patient with cone-dominated IRD, resembling initially achromatopsia and carrying biallelic compound heterozygous variants in CEP290, broadening the spectrum of CEP290-associated disease.

References

Coppieters F, Lefever S, Leroy BP, De Baere E (2010) CEP290, A gene with many faces: mutation overview and presentation of CEP290 base. Hum Mutat 31(10):1097–1108. https://doi.org/10.1002/humu.21337

Preising M, Schneider U, Friedburg C, Gruber H, Lindner S, Lorenz B (2019) The phenotypic spectrum of ophthalmic changes in CEP290 mutations. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd 236(3):244–252. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0842-3250

Roosing S, Riemslag F, Zonneveld-Vrieling M, Talsma H, Klessens-Godfroy F, den Hollander A, van den Born I (2017) A rare form of retinal dystrophy caused by hypomorphic nonsense mutations in CEP290. Genes (Basel) 22 8(8):208. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes8080208

Feldhaus B, Weisschuh N, Nasser F, Den Hollander A, Cremes F, Zrenner E, Kohl S, Zobor D (2020) CEP290 mutation spectrum and delineation of the associated phenotype in a large german cohort: a monocentric study. Am J Ophthalmol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2019.11.012

Rafalska A, Tracewska A, Turno-Krecicka A, Szafraniec M, Misiuk-Hojto M (2020) A mild phenotype caused by two novel compound heterozygous mutations in CEP290. Genes (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11111240

Cideciyan A, Aleman T, Jacobson S, Khanna H, Sumaroka A, Geoffrey K, Aguirre G, Schwartz S, Windsor E, Bo Chang S, Stone E (2007) Swaroop A (2007) Centrosomal-ciliary gene CEP290/NPHP6 mutations result in blindness with unexpected sparing of photoreceptors and visual brain: implications for therapy of Leber congenital amaurosis. Hum Mutat doi 28(11):1074–1083

Wiszniewski W, Lewis R, Stockton D, Peng J, Mardon G, Chen R, Lupski J (2010) Potential involvement of more than one locus in trait manifestation for individuals with Leber congenital amaurosis. Hum Genet 129(3):319–327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-010-0928-y

Bachmann-Gagescu R, Dempsey J, Phelps I, O'Roak B, Knutzen D, Rue T, Ishak G, Isabella C, Gorden N, Adkins J, Boyle E, de Lacy N, O'Day D, Alswaid A, Radha Ramadevi A , Lingappa L, Lourenço C, Martorell L, À Garcia-Cazorla, Ozyürek H, Haliloğlu G, Tuysuz B, Topçu M, University of Washington Center for Mendelian Genomics, Chance P, Parisi M, Glass I, Shendure J, Doherty D (2015) Joubert syndrome: a model for untangling recessive disorders with extreme genetic heterogeneity. J Med Genet 52(8):514-22. https://doi.org/10.1136/jmedgenet-2015-103087

Den Hollander A, Koenekoop R, Yzer S, Lopez I, Arends M, Voesenek K, Zonneveld M, Strom T, Meitinger T, Brunner H, Hoyng C, Van den Born I, Rohrschneider K, Cremers F (2006) Mutations in the CEP290 (NPHP6) gene are a frequent cause of leber Congenital Amaurosis. Am J Hum Genet 79(3):556–561. https://doi.org/10.1086/507318

Hess R, Sharpe L, Nordby K (1990) Total colour blindness: an introduction. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 253–289

Hess R, Sharpe L, Nordby K (1990) Night vision: basic, clinical and applied aspects. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 253–289

Thiadens A, Slingerland N, Roosing S, Van Schooneveld M, Van Lith-Verhoeven J, Van Moll-Ramiren N, Van den Born I, Hoyng C, Cremers F, Klaver C (2009) Genetic etiology and clinical consequences of complete and incomplete achromatopsia. Ophthalmology 116(10):1984–9.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.03.053

Zobor D, Werner A, Stanzial F, Benedicenti F, Rudolph G, Kellner U, Hamer C, Andreasson S, Zobor G, Strasse T, Wissinger B, Kohl S, Zrenner E (2017) The clinical phenotype of CNGA3-related achromatopsia: pretreatment characterization in preparation of a gene replacement therapy trial. IOVS 58:821–832. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.16-20427

Thiadens A, Somervuo V, Van den Born I, Roosing S, Schooneveld M, Kujipers R, Moll-Ramirez N, Cremes F, Hoyng C, Klaver C (2010) Progressive loss of cones in achromatopsia: an imaging study using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. IOVS 51:5952–5957. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.10-5680

Pompe M, Vrabic N, Volk M, Meglic A, Jarc-Vidmar M, Peterlin B, Hawlina M, Fakin A (2021) Disease progression in CNGA3 and CNGB3 retinopathy; characteristics of slovenian cohort and proposed oct staging based on pooled data from 126 patients from 7 studies. Curr Issues Mol Biol 43(2):941–957. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb43020067

Weisschuh N, Mazzola P, Bertrand M, Haack T, Wissinger B, Kohl S, Stingl K (2021) Clinical characteristics of POC1B-associated retinopathy and assignment of pathogenicity to novel deep intronic and non-canonical splice site variants. Int J Mol Sci 22(10):5396. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22105396

Testa F, Sodi A, Signorini S, Di Iorio V, Murro V, Brunetti-Pierri R, Valente M, Karali M, Melillo P, Banfi S, Simonelli F (2021) Spectrum of disease severity in nonsyndromic patients with mutations in the CEP290 gene: a multicentric longitudinal study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 62(9):1. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.62.9.1

Weleber R, Pennesi M, Wilson D (2016) Results at 2 years after gene therapy for RPE65-deficient Leber congenital amaurosis and severe early-childhood-onset retinal dystrophy. Ophthalmology 123:1606–1620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.03.003

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AB reviewed the patient data with the supervision of KS and wrote the first draft. KS, SK, UG and KSch performed the clinical and genetic examinations, analyses and consulting. All authors reviewed the draft and contributed to the manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this manuscript.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients’ parents for publication of this case report.

Statement of human rights

The article was written in agreement with the declaration of Helsinki.

Statement on the welfare of animals

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Binder, A., Kohl, S., Grasshoff, U. et al. An early onset cone dystrophy due to CEP290 mutation: a case report. Doc Ophthalmol 147, 203–209 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10633-023-09940-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10633-023-09940-z