Abstract

Reducing individual fossil fuel use is an important component of climate change mitigation, but motivating behaviour change to achieve this is difficult. Protection motivation theory (PMT) is a psychological framework that outlines the conditions under which people are more likely to be persuaded to take a specific response or action. This experimental study investigated the impact six different protection motivation theory-based messages had on intention to reduce fossil fuel use in a sample 3803 US adults recruited via Amazon Mechanical (MTurk). Only messages targeting self-efficacy and response efficacy increased intention to reduce fossil fuel use relative to the control message. However, only the self-efficacy message had an impact on its target construct (i.e. self-efficacy). As such, the mechanism for action for the response efficacy message is unclear. Furthermore, while the current study demonstrates that many of the PMT-related messages did not achieve changes in intention, this it is still possible that messages targeting these constructs could still lead to changes in intention in other modalities and when other message content is used. Given the urgency of responding to climate change, the potential for additive benefits of combining effective PMT-based messages should be considered irrespective of their mechanism as should research focused on how to effectively target other key PMT constructs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Anthropogenic climate change represents an unprecedented existential threat to humanity (IPCC, 2021). According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) sixth assessment report, there is now robust evidence to suggest that a 2 °C increase in average global temperatures from pre-industrial levels will result in a high risk of exacerbated global food and water shortages, heat stress, disease, and extreme weather events (IPCC, 2018). Consumption of fossil fuels is among the most influential factors in climate change (Höök & Tang, 2013). Large-scale reductions in fossil fuel consumption, such as rapid transitions to renewable energy lead by business and governments, can lead to substantial reductions in total greenhouse emissions (Dietz, Gardner, Gilligan, Stern, & Vandenbergh, 2009). Yet encouraging individual behaviour is still important within this context, despite having less impact on carbon emission reduction when compared to enacting effective governmental and industry change (Steg, 2018). Not only can this strategy help to ensure the general population continues to be motivated and engage with climate action in all its forms (be it individual or collective), targeting and/or modifying individual behaviours can serve as “behavioural wedges”—low-cost, voluntary behavioural solutions individuals engage in which help to mitigate climate change but do not require governmental or industry intervention (Gilligan et al., 2010). Therefore, while individual behaviour change will not meet emissions targets alone, it is still an important part of the world’s response as it assists to further mitigate the impact of climate change (Dietz, Gardner, Gilligan, Stern, & Vandenbergh, 2009). In this regard, despite the availability of low-carbon and renewable energy sources, transition away from fossil fuels remains suboptimal (International Energy Agency, 2017).

A pressing goal in current efforts for climate change mitigation is therefore the development and implementation of effective evidence-based messaging strategies to promote the reduction of fossil fuel consumption by individuals (Clayton et al., 2015). However, there is currently a lack of consensus among researchers on how such messages should be framed to maximise their effectiveness. The desirability of fear-based appeals—which seek to evoke adaptive behaviour by stimulating fear or threats—has been uncertain (Kok, et. Al, 2018; Reser & Bradley, 2017). Meta-analysis indicates that across a wide range of behavioural domains, fear appeals are effective at engendering change in both intention and behaviour (see Bigsby & Albarracín 2022). More specifically, fear appeals have demonstrated effectiveness in eliciting pro-environmental behaviour and attitude change (Tannenbaum et al., 2015) such as increasing support for energy saving measures (Meijnders, Midden, & Wilke, 2001), and intentions to engage in pro-environmental collective action (Zomeren, Spears, & Leach, 2010), and intention to engage in green consumerism (Shin et. Al., 2017). That said, fear appeals have also been criticised for their tendency to evoke anxiety (O’Neill & Nicholson-Cole, 2009), and questions have been raised regarding their true effectiveness in achieving behavioural engagement in pro-environmental action rather than more distal outcomes such as policy support (O’Neill & Nicholson-Cole, 2009). Their use in circumstances where individuals have limited efficacy has also been criticised on ethical and practical grounds (Kok, et. Al, 2018). This has prompted calls for greater use of positively framed appeals that engender a sense of hope and efficacy (O’Neill & Nicholson-Cole, 2009; Stern, 2012), or focus on the potential benefits of climate action in promoting a better society (Bain et al., 2012). However, the evidence regarding effectiveness of positive frames has also been mixed (Ettinger, Walton, Painter, & DiBlasi, 2021), with some studies even suggesting that positively framed messaging may reduce motivations for mitigation (Hornsey & Fielding, 2016) and a recent meta-analysis indicating that combined fear and efficacy messages performed no better than fear only messages (Bigsby & Albarracín 2022). Such inconsistencies in the literature highlight the need for an overarching theoretical framework that accounts for the mechanisms by which fear appeals and positive appeals influence pro-environmental behaviour. To this end, we draw on protection motivation theory (PMT: Rogers, 1975), a framework of persuasion and behaviour change that accounts for both positive co**-based appraisals and threat-based (or fear-based) appraisals as relevant cognitive pathways to adaptive or maladaptive behaviour change. Specifically, the current study seeks to elicit changes in intentions to reduce their fossil fuel consumption through messages informed by the PMT framework.

1.1 Protection motivation theory

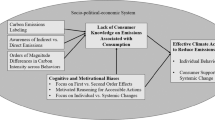

Protection motivation theory is a socio-cognitive model of persuasion and behaviour change that identifies specific appraisal processes that determine whether an individual’s protection motivation is activated in response to threatening information (or fear appeals), which in turn leads them to engage in (mal)adaptive behaviour (Rogers, 1975). The starting premise of PMT is that behaviour is determined by the two parallel cognitive processes—threat appraisal and co** appraisal (see Fig. 1; Rogers, 1975; Norman, Boer, Seydel, and Mullan , 2015). Importantly, PMT provides conceptual clarity to both threat and co** processes by differentiating each of these appraisal processes into six components. Threat appraisal is determined by three psychological constructs: threat severity (perceived seriousness of the threat); susceptibility (perceived vulnerability to the threat); and maladaptive response rewards (perceived benefits of engaging in a maladaptive response such as avoidance or denial: Norman, Boer, Seydel, & Mullan, 2015). According to PMT, individuals will experience the greatest threat appraisal when maladaptive response rewards are low, but susceptibility and severity are high. Co** appraisal is determined by three constructs: response efficacy (perceived effectiveness of behaviour in averting a threat); self-efficacy (perceived ability to perform the behaviour); and response costs (perceived costs and barriers associated with behaviour adoption; Norman, Boer, Seydel, and Mullan, 2015). The greatest level of co** appraisal will occur when response costs are low, but response efficacy and self-efficacy are high.

Although initially developed in the context of health interventions, PMT has broad applicability in domains with similar threat/co** dyads and has been applied effectively to predict behaviour change in a broad range of contexts such as information security (Menard, Bott, & Crossler, 2017) and flood mitigation (Bubeck, Wouter Botzen, Laudan, Aerts, & Thieken, 2018). Further, previous work has shown that PMT-based messages can be effective in changing beliefs and behaviour (Floyd, Prentice-Dunn, & Rogers, 2000; Milne, Sheeran, & Orbell, 2000). By investigating messages that elicit change in different PMT constructs, researchers have identified messages most effective at increasing a given behaviour. For example, Pechman et al. (2003) found that anti-smoking advertisements were most effective in reducing smoking intentions among adolescents when they elicited changes in cognitions of severity of social risks of smoking, self-efficacy in refusing cigarette offers, vulnerability to social disapproval risks, and vulnerability to health risks.

1.2 Protection motivation theory and pro-environmental behaviour

The potential magnitude and severity of consequences posed by unmitigated climate change mean that fear appeals are the inevitable starting point of many messaging campaigns that target climate change-mitigating behaviours (Cismaru, Cismaru, Ono, & Nelson, 2011; Reser & Bradley, 2017). However, as noted above, research also suggests that over-emphasis on fear alone may hinder adaptive behaviour change by engendering feelings of anxiety and hopelessness (O’Neill & Nicholson-Cole, 2009). As a theoretical framework that accounts for both threat and co** appraisal pathways as determinants of behaviour change, PMT has clear conceptual applicability to this context. This applicability was demonstrated by Cismaru et al. (2011), who found in a qualitative analysis of eleven major climate change campaigns that nine contained information that corresponded to at least four PMT constructs. However, the same analysis found that none of the campaigns had specified an underlying theory for the development of campaign messages. Such findings not only highlight the natural affinity of PMT as a framework for climate change messaging, but also the importance of systematically evaluating the effectiveness of behaviour change frameworks in predicting real-world environmental behaviour and attitude change (Cismaru et al. 2011; Kidd et al., 2019).

To this end, a growing number of studies have sought to evaluate the effectiveness of constructs derived from PMT in predicting a wide range of pro-environmental attitudes and behaviours. According to a recent review of twenty-two such studies by Kothe et al. (2019), there is now broad empirical support for the application of PMT to understand pro-environmental intentions. Indeed, there is now cross-sectional evidence for a relationship between all six PMT constructs and pro-environmental intentions (Kothe et al., 2019). Specifically, in terms of threat appraisals, both threat severity and susceptibility have been found to positively predict intentions to purchase of electric vehicles (Bockarjova & Steg, 2014), support for pro-environmental government policies (e.g. Lam, 2015), and intentions to increase a composite range of pro-environmental behaviours (e.g. Rainear & Christensen, 2017). Comparatively few studies have included a measure of maladaptive response rewards (Kothe et al., 2019); however, preliminary evidence has demonstrated that it is a negative predictor of electric vehicle purchasing intentions (Bockarjova & Steg, 2014) and intentions to adopt sustainable behaviours (Almarshad, 2017).

In terms of co** appraisals, both self-efficacy and response efficacy have been found to positively predict a range of pro-environmental behaviours. This includes such outcomes as intended and actual energy-saving tourist behaviours (Horng, Hu, Teng, & Lin, 2014), intentions to engage in green consumer behaviours (Ibrahim & Al-Ajlouni, 2018; Rainear & Christensen, 2017, Rainear & Christensen, 2022), and electric vehicle purchasing intentions (Bockarjova & Steg, 2014). Response costs have also been found to negatively predict electric vehicle purchasing intentions and intentions to engage in green consumer behaviours (Bockarjova & Steg, 2014; Rainear & Christensen, 2017). These studies support the value of applying the conceptualisations of threat and co** appraisal constructs proposed by PMT as a framework for guiding development of message-based interventions targeting environmental behaviour. However, to date, almost all studies investigating PMT in the context of pro-environmental behaviour have only included a subset of PMT constructs, meaning that few studies have evaluated PMT as an overall theoretical framework for predicting pro-environmental attitudes and behaviour (Kothe et al., 2019). This is despite frequent recommendations for the use of PMT in designing pro-environmental campaigns (see Cismaru, et al., 2011; Nelson et al., 2011; Scharks, 2016). Further, despite calls for experimental tests of psychological theory within environmental and conservation psychology (e.g. Kidd et al., 2019; Nelson et al., 2011), few studies have sought to test causal connections between PMT constructs and behaviour change intentions in this context and even fewer studies looking specifically at actions directly related to climate change mitigation (see Kothe et al., 2019).

While cross-sectional studies may indicate relationships between theorised constructs that exist within a sample, they do not necessarily indicate the suitability of the construct as a target for intervention, as they may already be negatively skewed in the population (Crutzen et al., 2017), or because they involve perceptions that are impractical to shift using non-invasive message-based interventions. The use of experimental tests is therefore an important step in evaluating the effectiveness of intervention strategies that target specific psychological mechanisms of interest and in identifying the most suitable target mechanisms for changing the desired behaviour in a given context.

1.3 The current study

In one of the largest and most comprehensive studies applying the whole PMT framework to target a pro-environmental behaviour, we systematically investigated the impact of short message-based interventions that target PMT constructs on intention to reduce fossil fuel consumption. Each message targeted one PMT construct; the impact of each construct on intention and its target construct was examined.

1.4 Hypotheses

-

The primary outcome was the intention to reduce fossil fuel consumption. It was hypothesised that intervention messages would increase intention relative to control.

-

The secondary outcomes were the PMT constructs. Consistent with the core premises of PMT (Cismaru et al., 2011; Rogers, 1975), it was hypothesised that intervention messages targeting a given PMT construct would affect that construct relative to control. Specifically, relative to control, the:

-

a.

Response cost message would decrease perceived response cost

-

b.

Maladaptive response rewards message would l decrease perceived maladaptive response rewards

-

c.

Response efficacy message would increase perceived response efficacy

-

d.

Severity message would increase perceived severity

-

e.

Susceptibility message would increase perceived susceptibility

-

f.

Self-efficacy message would increase self-efficacy

-

a.

2 Methods

This study was pre-registered using the template developed by van’t Veer and Giner-Sorolla (2016) https://osf.io/2g6bq/.

2.1 Participants

Participants were recruited via Amazon Mechanical (MTurk) to take part in a study entitled “Short study of responses to messages about scientific issues” in exchange for $1.10USD in Amazon credit. To avoid the potential of participants self-selecting themselves in or out of the study based on its topic, climate change or pro-environmental behaviour was not mentioned in the recruitment notice or plain language statement.

Sample size was determined a priori; we aimed to recruit a minimum of 526 participants per cell to detect an effect of d =.2, with 80% power and alpha of 0.0083. To account for missingness, we oversampled each cell by 20, leading to a recruitment target of 546 per condition and a total recruitment target of 3822. After removal of duplicate and incomplete submissions, 3803 participants were included in this study.

Gender identity was measured using a free-text question, and so was manually categorised post data collection. Four responses could not be categorised (i.e. they did not appear to reflect gender identity: “%” or “40”). Three participants reported an age below the allowed age for registration on MTurk or above 200 years. For both gender and age, these problematic values were converted to missing but data were otherwise retained (see Table 1 for a summary of participant characteristics).

2.2 Procedure

Participants completed an online questionnaire that included all measures and the experimental manipulation via Qualtrics. The first component of the questionnaire included demographic items. Participants were then randomly allocated (by Qualtrics) to one of the six intervention groups or control. Individuals allocated to receive an intervention message were shown a message-related instruction and then the target message. Individuals in the control group did not receive the instruction or message and instead proceeded directly to the next part of the survey. Participants were not notified of their condition. In the third part of the questionnaire, participants completed the PMT questionnaire. The order of items within the PMT questionnaire was randomised to reduce order effects. At the conclusion of the study, participants were invited to provide feedback on the survey via a free-text response box. The study took approximately 5–10 min to complete. Data for this project was collected concurrently with data for a second project in 2019 (described at https://osf.io/nhcfv?view_only=9ed9068c2f1d42eaa0c1a27430457df9). Each participant took part in only one project. Although the projects were not intended to be analysed or reported together, their structural similarity could cause unexpected effects for participants who participated in both (e.g. unblinding). The intention to analyse and report the studies separately was documented in the pre-registration.

2.3 PMT-related messages

Participants were randomised to receive one of six intervention messages or to a no message control group. Each intervention message was designed to target a single PMT construct. These final six messages were selected from a larger pool of candidate messages which were pilot tested to maximise the likelihood that each message would successfully manipulate the target construct. Message selection during this pilot testing occurred as follows. First, a set of 24 candidate messages (four per PMT construct) were developed by the first two authors and reviewed by the third author. These messages were then tested in a pilot study with a convenience sample of 546 Australian adults. Participants in the pilot study viewed a single candidate message relating to climate change or pro-environmental behaviour and responded to a single item related to the construct the measure that was intended to target (e.g. if a participant was given the severity message, they then completed a single item measure of severity). As per the pre-registered message selection strategy, the mean response was calculated for each candidate message, with the candidate message with the largest (or smallest in the case of maladaptive response rewards and response costs) mean value on the construct measure chosen for use within the current study. More details concerning the pilot testing and subsequent message selection strategy for the current can be found at the projects OSF webpage (see: https://osf.io/nhcfv?view_only=9ed9068c2f1d42eaa0c1a27430457df9).

The final six messages used for the current study are outlined below:

-

“The climate is changing. Climate change will lead to serious consequences in the United States including increased and more prolonged drought. Climate change is already contributing to water shortages around the globe.” – Severity

-

“The climate is changing. These changes put everyone at risk. Whether or not you realize it, climate change is already affecting your life, by making extreme weather events more frequent and increasing food prices.” – Susceptibility

-

“The climate is changing. Some people believe that climate change will lead to a more comfortable climate due to higher average daytime temperatures, but researchers agree that even in developed countries changes to our climate will disrupt basic necessities like food, clean air, and clean water.” – Maladaptive response rewards

-

“We need to reduce our use of fossil fuels in order to reduce the risks of climate change. Many households can save hundreds of dollars each year simply by installing more efficient lights. Small changes like this make a difference and allow you to save money and help the environment at the same time.” – Response efficacy

-

“We need to reduce our use of fossil fuels in order to reduce the risks of climate change. Reducing your fossil fuel dependence is easy. You can change your use of fossil fuels with lots of little steps by driving less or doing one big load of laundry rather than multiple small loads.” – Self-efficacy

-

“We need to reduce our use of fossil fuels in order to reduce the risks of climate change. It doesn’t take a lot of time and effort to reduce your fossil fuel usage, you can do something as simple as changing your electricity supply to one using more renewable energy sources.” – Response costs

2.4 Measures

2.4.1 Demographics

Participants completed a short demographic questionnaire at the beginning of the study. This included items regarding age, gender, highest level of education completed, annual household income, and political orientation.

Political orientation was measured using three self-placement items. Participants were asked to indicate “When it comes to … would you consider yourself” with reference to “politics in general,” “economic issues”, and “social issues.” Each item was measured on a 0–10-point scale (0 = “Very Liberal”; 10 = “Very Conservative”).

2.4.2 Intention

Intention was measured as the mean of three items (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) regarding the referent behaviour “reduce my use of fossil fuels from now on.” Higher scores indicate greater intention to reduce fossil fuel consumption (α = 0.94).

2.4.3 Severity

Severity was measured as the mean of three items (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) that indicated that the negative impact of climate change was severe. Higher scores indicate greater perceived severity of climate change (α = 0.85).

2.4.4 Susceptibility

Susceptibility was measured as the mean of three items (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) that indicated that participants are vulnerable to the negative impacts of climate change. Higher scores indicate greater perceived susceptibility to negative impacts of climate change (α = 0.83).

2.4.5 Maladaptive response rewards

Maladaptive response rewards was measured as the mean of three items (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) that indicated that there are benefits of doing nothing regarding climate change or to climate change occurring. Higher scores indicate greater perceived maladaptive response rewards (α = 0.51).

2.4.6 Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy was measured as the mean of three items (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) that indicated that individuals would be capable of reducing their use of fossil fuels. Higher scores indicate greater self-efficacy (α = 0.71).

2.4.7 Response efficacy

Response efficacy was measured as the mean of three items (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) that indicated that reducing their use of fossil fuels would be effective in reducing climate change. Higher scores indicate greater perceived response efficacy (α = 0.82).

2.4.8 Response costs

Response costs was measured as the mean of three items (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) that indicated that there are costs (including non-financial costs) associated with reducing fossil fuels. Higher scores indicate greater perceived response costs (α = 0.74).

2.5 Data analysis

We used R (Version 4.1.1; R Core Team, 2020) and the R-packages broom (Version 0.7.9; Robinson, Hayes, & Couch, 2021), cowplot (Version 1.1.1; Wilke, 2020), dplyr (Version 1.0.7; Wickham, François, Henry, & Müller, 2021), ggplot2 (Version 3.3.5; Wickham, 2016), here (Version 1.0.1; Müller, 2020), knitr (Version 1.34; ** review. Australian Journal of Psychology." href="/article/10.1007/s10584-023-03489-1#ref-CR25" id="ref-link-section-d21251831e3078">2019). Given this, the aim of this study was to systematically investigate the impact of messages targeting the six PMT constructs on intention to reduce fossil fuel consumption. It was hypothesised that these messages would increase intention to reduce fossil fuel use relative to control (Hypothesis 1) and that each of the messages would increase their target PMT construct (Hypothesis 2).

In the current study, messages designed to increase self-efficacy and response efficacy were effective in increasing fossil fuel reduction intentions when compared to control, providing partial support for Hypothesis 1. However, other messages that targeted severity, susceptibility, and maladaptive response rewards and response costs did not contribute to fossil fuel reduction intentions. Furthermore, of the six PMT constructs, only the self-efficacy message changed its target construct of self-efficacy, providing partial support for Hypothesis 2. This indicates that the remaining five PMT-related messages were not effective in changing their target construct. Exploratory indirect effect analyses suggest that the self-efficacy message may have impacted intention by influencing self-efficacy. However, the response efficacy message did not increase response efficacy and instead appeared to influence self-efficacy and response costs. While effect sizes suggest that, relative to control, the response efficacy message had a larger impact on intention than the self-efficacy message [Hedge’s g response efficacy: 0.24; Hedge’s g self-efficacy: 0.22]; this difference is small, and given the differences, the apparent mechanisms of action should be interpreted with caution.

That the self-efficacy and response-efficacy messages were found to increase one’s intention to reduce their fossil fuel use aligns with growing correlational research that demonstrates different efficacy types are positively related to pro-environmental behaviour and climate action (Bostrom et al., 2019; Doherty & Webler, 2016; Scafuto, 2018). This includes self-efficacy (the belief in one’s capacity to successfully perform climate action), response-efficacy (the belief that these climate actions will be effective), and collective-efficacy (the belief in one’s group’s ability to achieve climate change related goals) (Roser-Renouf et al., 2014; Scafuto, 2021). Nevertheless, this prior research has yet to systematically test the impact of self-efficacy messages in the context of the PMT as we have done. Further still, one previous study found no difference between individuals exposed to self-efficacy and control messages in intention to reduce carbon footprint (Greenhalgh, 2011). However, their results suggested a failure of the self-efficacy manipulation. As such, our results provide the first piece of experimental evidence of a causal relationship between self-efficacy, as conceptualised by PMT, and intention in the context of pro-environmental behaviour.

In the context of response efficacy messages, only a small number of studies have sought to experimentally manipulate response efficacy in the context of pro-environmental behaviour (Ahren, 2008; Kantola, Syme, & Nesdale, 1983). In one study, the response efficacy message did not change response efficacy (Ahern, 2008). While another found that their message induced change in response efficacy, it did not lead to increased intention to conserve water (Kantola et al., 1983). In our sample, the response efficacy group had higher average intention to reduce fossil fuel consumption than the control group; however, this was not accompanied by differences in response efficacy itself. Taken together with the previous studies (Ahern, 2008; Kantola, Syme, & Nesdale, 1983), this suggests there is limited evidence for changes in response efficacy leading to changes in intention within the context of pro-environmental behaviour. While the current study did pilot test, the response efficacy message to ensure it increased response efficacy, it is still possible that this process did not generate a message which adequately reflected response efficacy beliefs in the pro-environmental context. Therefore, this finding at least partially reflects the challenges in designing effective response efficacy messages, rather than simply implying a lack of a causal relationship between response efficacy and intention. Further research should look to examine the beliefs that underpin response efficacy in this context, including via qualitative methods, to develop messages which can further test the potential relationship between response efficacy and pro-environment outcomes.

Findings of the current study also indicated that messages targeting response costs, severity, susceptibility, and maladaptive response rewards also did not lead to changes in intention or in their target constructs. This is the first study to attempt to experimentally manipulate maladaptive response rewards or response costs (Kothe et al., 2019), and previous attempts to experimentally manipulate severity and susceptibility to bring about changes in intention have had limited success. For instance, while Huth, McEvoy, Morgan, and others (2018) reported an effect of a severity manipulation on purchasing intention, Chen (2016) found that individuals in their “high threat” condition actually reported lower evoked fear than their “low threat” condition in the context of an intervention that simultaneously targeted susceptibility and severity. Further still, Kantola et al. (1983) found that a message that was successful in increasing severity had no impact on intention. More recently, Rainear and Christensen (2022) found that while the group-wide impact of a threat-based public service announcement was not significant, these findings were moderated by pre-existing pro-environmental beliefs. For individuals with favourable pro-environmental beliefs, the message had a positive, although not significant, impact on both response efficacy and self-efficacy, and for those with unfavourable pre-existing beliefs, the message had a negative effect on both constructs. As a result, evidence for a causal relationship between threat appraisal constructs from the PMT and intentions to engage in pro-environmental behaviours is currently very limited. Nevertheless, it is important to note that while the messages targeting response costs, severity, susceptibility, and maladaptive response rewards did not result in changes to intention or to their target constructs, this does not automatically mean that the affiliated construct is ineffective in this context. This lack of impact from these PMT related constructs may have been a consequence of the message content itself and its alignment with the target outcome of fossil fuel reduction. Therefore, while the selection of messages for the current study was based on pilot data, messaging studies can still fail on the basis that other messages could be more effective because of differential message effects for different segments of the population. It is possible that different PMT-related messages which contain alternative information to our messages, such as content that is perceived by individuals as more closely aligned with the target outcome, could have been more effective for the current study’s outcome variable (or for other types of pro-environmental outcomes more broadly). The design of messages that effectively alter these PMT constructs is a necessary precondition for evaluating causality and as such should be a focus of future research.

One potential avenue to guide the development of theoretically driven intervention components comes from work on behaviour change techniques within the field of health psychology (Michie et. al, 2008, Michie & Johnston, 2012). Health psychology researchers have worked to identify behaviour agnostic common “behaviour change techniques” that can be used in intervention design and evaluation across a large range of behavioural domains. This work that could be useful for those seeking to build on the finding that self-efficacy messages can increase intention and for researchers who wish to identify messages that might be more effective at targeting other PMT constructs. For example, the severity message used in this study would be classified as a use of the behaviour change technique “Information about social and environmental consequences”, but messages that seek to increase the salience of those consequences or provoke anticipated regret would be an alternate strategy to targeting that construct (Carey et. al., 2019, Michie et. al., 2013). Similarly, while the message content used to target self-efficacy in this study would be classified as using the behaviour change technique “Verbal persuasion about capability”, self-efficacy can also be targeted by encouraging individuals to focus on their past successes or engage in mental rehearsal of successful performance of a target behaviour (Carey et. al., 2019, Michie et. al., 2013). The advantage of conceptualising message components in this way is that it makes clear that where it is not feasible to create realistic self-efficacy messages that are personalised to the individual or for some behaviours, generic prompts or strategies that are likely to be more broadly applicable may be useful to encouraging behaviour change. To our knowledge, this is the largest study to date to experimentally investigate pro-environmental behaviour change via all six PMT constructs (see: Kothe et al., 2019). As such, the study provides important insights regarding the applicability and effectiveness of messaging derived from the PMT framework in this context. The study provides limited support for messages that seek to target co** appraisal-related constructs from the PMT but provides no evidence to support the use of messages that target threat appraisal constructs. This provides an interesting contribution to the ongoing debate as to the relative utility of fear vs. hope based appeals in the context of pro-environmental behaviour change. As this study demonstrates, even when messages are effective in increasing intention, it cannot be assumed to be a function of change in the target construct (c.f. Chen, 2016). Such manipulation checks are often not conducted or reported within the PMT pro-environmental literature (Kothe et al., 2019) or in experimental papers based on similar theoretical approaches (e.g. Hardeman et al., 2002). These results highlight the importance of such manipulation checks to theory testing, particularly as the conceptual similarity between PMT constructs may make the creation of messages that target just one PMT construct difficult. Such findings may also be consequential in the development of messaging interventions based on PMT constructs, as they question the practical utility of constructing messages that are narrowly framed to target a single causal mechanism. The pilot stage of this project evaluated a set of candidate messages to select the message that appeared most likely to successfully manipulate the target construct; however, due to resource constraints we were not able to evaluate whether the message also led to spill over effects on other PMT constructs. This means we were unable to specifically select messages that led to change in the targeted construct without changes to any other PMT construct under study. Given the urgency of addressing climate change, identifying these causal mechanisms may be of limited importance when presented with an approach to changing intentions or behaviour that appears to be effective. More specifically, if it is the case that the response efficacy message described in this study is effective at increasing intention without increasing response efficacy itself, it may be fruitful to examine the longer-term impacts of the message even if the mechanism action remains unclear.

A key limitation of the current study is that it only measured changes in intentions to reduce fossil fuel consumption and did not measure effects on real-world behaviour. It is important to note that the core theoretical premise of PMT is the conceptualization of mediational processes that lead to changes in intention to engage in applicable (mal)adaptive responses (Rogers & Prentice-Dunn, 1997). Further, intentions to engage in adaptive behaviour have been found in past work to closely align with real-world behavioural changes across a wide range of contexts (Sheeran & Webb, 2016). However, given the urgency of real-world behaviour change in the effort for climate change mitigation, future studies seeking to implement messaging based on PMT should also investigate whether changes in intention do indeed predict downstream changes in behaviour.

4.1 Conclusion

Overall, the results of this study suggest that efficacy-based messages (specifically messages targeting self-efficacy and response efficacy) can be effective at increasing intention to engage in pro-environmental behaviours, such as one’s intention to reduce their fossil fuel use. However, as the effects were only evaluated immediately post message presentation, the extent to which these effects can be maintained over time requires further examination as does the extent to which the effects result in subsequent increases in engagement in actual pro-environmental behaviours. Further, given that the effects are small and would reasonably be expected to diminish over time, it may be useful to consider whether efficacy messages could be combined to increase their impact on pro-environmental behaviour.

Data availability

The de-identified data, all study materials, and the data analysis scripts for this study are openly available at: https://osf.io/2trbk/?view_only=cc4020ffcfd64375911dafcd3d81ee81.

References

Ahern L (2008) Psychological responses to environmental messages: the roles of environmental values, message issue distance, message efficacy and idealistic construal. The Pennsylvania State University

Almarshad SO (2017) Adopting sustainable behavior in institutions of higher education: a study on intentions of decision makers in the MENA region. European Journal of Sustainable Development 6(2):89–110

Aust, F., & Barth, M. (2020). papaja: create APA manuscripts with R markdown. https://github.com/crsh/papaja

Bockarjova M, Steg L (2014) Can protection motivation theory predict pro-environmental behavior? Explaining the adoption of electric vehicles in the Netherlands. Global Environmental Change 28:276–288

Bostrom A, Hayes AL, Crosman KM (2019) Efficacy, action, and support for reducing climate change risks. Risk analysis 39(4):805–828. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.13210

Bubeck P, Wouter Botzen W, Laudan J, Aerts JC, Thieken AH (2018) Insights into flood-co** appraisals of protection motivation theory: empirical evidence from Germany and France. Risk Analysis 38(6):1239–1257

Chen M-F (2016) Impact of fear appeals on pro-environmental behavior and crucial determinants. International Journal of Advertising 35(1):74–92

Cismaru M, Cismaru R, Ono T, Nelson K (2011) “Act on climate change”: an application of protection motivation theory. Social Marketing Quarterly 17(3):62–84

Clayton S, Devine-Wright P, Stern PC, Whitmarsh L, Carrico A, Steg L et al (2015) Psychological research and global climate change. Nature Climate Change 5(7):640

Crutzen R, Peters G-JY, Noijen J (2017) Using confidence interval-based estimation of relevance to select social-cognitive determinants for behavior change interventions. Frontiers in Public Health 5:165

Dietz T, Gardner GT, Gilligan J, Stern PC, Vandenbergh MP (2009) Household actions can provide a behavioral wedge to rapidly reduce US carbon emissions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106(44):18452–18456

Doherty KL, Webler TN (2016) Social norms and efficacy beliefs drive the alarmed segment’s public-sphere climate actions. Nature Climate Change 6(9):879–884. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3025

Ettinger J, Walton P, Painter J, DiBlasi T (2021) Climate of hope or doom and gloom? Testing the climate change hope vs. fear communications debate through online videos. Climatic Change 164(1):1–19

Greenhalgh, T. (2011). Assessing a combined theories approach to climate change communication.

Hardeman W, Johnston M, Johnston D, Bonetti D, Wareham N, Kinmonth AL (2002) Application of the theory of planned behaviour in behaviour change interventions: a systematic review. Psychology and Health 17(2):123–158

Höök M, Tang X (2013) Depletion of fossil fuels and anthropogenic climate change—a review. Energy Policy 52:797–809

Horng J-S, Hu M-LM, Teng C-CC, Lin L (2014) Energy saving and carbon reduction behaviors in tourism–a perception study of Asian visitors from a protection motivation theory perspective. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research 19(6):721–735

Hornsey MJ, Fielding KS (2016) A cautionary note about messages of hope: focusing on progress in reducing carbon emissions weakens mitigation motivation. Global Environmental Change 39:26–34

Huth WL, McEvoy DM, Morgan OA, & others (2018). Controlling an invasive species through consumption: the case of lionfish as an impure public good. Ecological Economics 149:74–79.

Ibrahim H, Al-Ajlouni MMQ (2018) Sustainable consumption: insights from the protection motivation (PMT), deontic justice (DJT) and construal level (CLT) theories. Management Decision 56(3):610–633

International Energy Agency (2017) CO2 emissions from fuel combustion 2017, p 529

IPCC (2018) Global warming of 1.5°c. An IPCC special report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°c above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

Kantola S, Syme G, Nesdale A (1983) The effects of appraised severity and efficacy in promoting water conservation: an informational analysis. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 13(2):164–182

Kidd LR, Bekessy SA, Garrard GE (2019) Neither hope nor fear: empirical evidence should drive biodiversity conservation strategies. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 34(4):278–282

Kothe EJ, Ling M, North M, Klas A, Mullan BA, Novoradovskaya L (2019) Protection motivation theory and pro-environmental behaviour: a systematic map** review. Australian Journal of Psychology.

Lam S-P (2015) Predicting support of climate policies by using a protection motivation model. Climate Policy 15(3):321–338

Larmarange, J. (2021). Labelled: manipulating labelled data. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=labelled

Meijnders AL, Midden CJ, Wilke HA (2001) Role of negative emotion in communication about CO2 risks. Risk Analysis 21(5):955–955

Menard P, Bott GJ, Crossler RE (2017) User motivations in protecting information security: protection motivation theory versus self-determination theory. Journal of Management Information Systems 34(4):1203–1230

Milne S, Sheeran P, Orbell S (2000) Prediction and intervention in health-related behavior: a meta-analytic review of protection motivation theory. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 30(1):106–143

Müller, K. (2020). Here: a simpler way to find your files. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=here

Nelson K, Cismaru M, Cismaru R, Ono T (2011) Water management information campaigns and protection motivation theory. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing 8(2):163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-011-0075-8

Norman P, Boer H, Seydel ER, Mullan BA (2015) Protection motivation theory. In: Predicting and changing health behaviour: research and practice with social cognition models. Open University Press

O’Neill S, Nicholson-Cole S (2009) “Fear won’t do it” promoting positive engagement with climate change through visual and iconic representations. Science Communication 30(3):355–379

Pechmann C, Zhao G, Goldberg ME, Reibling ET (2003) What to convey in antismoking advertisements for adolescents: the use of protection motivation theory to identify effective message themes. Journal of Marketing 67(2):1–18

R Core Team (2020) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria Retrieved from https://www.R-project.org/

Rainear AM, Christensen JL (2017) Protection motivation theory as an explanatory framework for proenvironmental behavioral intentions. Communication Research Reports 34(3):239–248

Reser, J. P., & Bradley, G. L. (2017). Fear appeals in climate change communication. In Oxford research encyclopedia of climate science.

Revelle W (2020) Psych: procedures for psychological, psychometric, and personality research. Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych

Robinson D, Hayes A, Couch S (2021) Broom: convert statistical objects into tidy tibbles. R package version 0.7 5 https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=broom

Rogers RW (1975) A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change. The Journal Of Psychology 91(1):93–114

Rogers RW, Prentice-Dunn S (1997) Protection motivation theory. In: Handbook of health behavior research 1: personal and social determinants. Plenum Press, New York, NY, US, pp 113–132

Roser-Renouf C, Maibach EW, Leiserowitz A, Zhao X (2014) The genesis of climate change activism: from key beliefs to political action. Climatic change 125(2):163–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-014-1173-5

Scafuto F (2021) Individual and social-psychological factors to explain climate change efficacy: the role of mindfulness, sense of global community, and egalitarianism. Journal of Community Psychology. 49(6):2003–2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22576

Scharks T (2016) Threatening messages in climate change communication. University of Washington Retrieved from https://digital.lib.washington.edu:443/researchworks/handle/1773/36393

Sheeran P, Webb TL (2016) The intention–behavior gap. Social and personality psychology compass 10(9):503–518. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12265

Stern PC (2012) Fear and hope in climate messages. Nature Climate Change 2(8):572–573. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1610

Tannenbaum MB, Hepler J, Zimmerman RS, Saul L, Jacobs S, Wilson K, Albarracin D (2015) Appealing to fear: a meta-analysis of fear appeal effectiveness and theories. Psychological Bulletin 141(6):1178

Van't Veer AE, Giner-Sorolla R (2016) Pre-registration in social psychology—a discussion and suggested template. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 67:2–12

Wickham H (2016) ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer-Verlag, New York Retrieved from https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org

Wickham, H. (2021). Tidyr: tidy messy data. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=tidyr

Wickham, H., & Hester, J. (2021). Readr: read rectangular text data. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=readr

Wickham, H., François, R., Henry, L., & Müller, K. (2021). Dplyr: a grammar of data manipulation. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dplyr

Wilke, C. O. (2020). Cowplot: streamlined plot theme and plot annotations for ’ggplot2’. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=cowplot

**e Y (2015) Dynamic documents with R and knitr, 2nd edn. Chapman; Hall/CRC, Boca Raton, Florida Retrieved from https://yihui.org/knitr/

Yoshida, K., & Bartel, A. (2021). Tableone: create ’table 1’ to describe baseline characteristics with or without propensity score weights. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=tableone

Zomeren, M. van, Spears, R., & Leach, C. W. (2010). Experimental evidence for a dual pathway model analysis of co** with the climate crisis. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(4), 339–346

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. This research was supported in part by the Deakin University’s Health Research Capacity Building Grant Scheme (HAtCH). The funder had no involvement in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E J. Kothe: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing-Original Draft, Supervision, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition. M Ling: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Resources, Data curation, Writing-Original Draft, Visualization, Supervision, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition. B A. Mullan: Methodology, Writing-Review and Editing, Funding Acquisition. J J. Rhee: Writing-Review and Editing. A Klas: Writing-Review and Editing

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This project was approved by Faculty of Health Human Ethics Advisory Group at Deakin University (Reference: HEAG-H 118_2018) and complies with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to participate

All participants provided informed consent.

Consent to publish

All authors have provided consent to publish this manuscript in Climatic Change.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author note

Emily J. Kothe, Misinformation Lab, School of Psychology, Deakin University, Australia; Mathew Ling, Misinformation Lab, School of Psychology, Deakin University, Australia; Barbara A. Mullan, Health Psychology and Behavioural Medicine Research Group, Enable Institute, Curtin University, Perth, Australia; Joshua J Rhee, Misinformation Lab, School of Psychology, Deakin University, Australia; Anna Klas, Misinformation Lab, School of Psychology, Deakin University, Australia

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kothe, E.J., Ling, M., Mullan, B.A. et al. Increasing intention to reduce fossil fuel use: a protection motivation theory-based experimental study. Climatic Change 176, 19 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-023-03489-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-023-03489-1