Abstract

Aim

The present systematic review analyzes existing strategies and policies used for adult vaccination of seven countries of the European area, emphasizing weaknesses and strengths of immunization schedules. Selected countries were Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Italy, Spain, Sweden, and Romania.

Subject and methods

Three main scientific databases (PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science) were queried and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed. Studies assessing weaknesses or strengths factors, facilitators and barriers related to the adult vaccination plans were considered eligible. We included ten studies with a medium/high score at the quality assessment.

Results

The main barriers and strength factors for vaccination can be divided into the following categories: financial aspects (e.g., if the vaccine has a funding mechanism); logistic factors (e.g., convenience, opening times); factors related to healthcare professionals (e.g., recommendations, provision by different categories of healthcare professionals).

Conclusion

Substantial improvement in adult vaccination uptake is urgently necessary to decrease the burden of infectious disease on healthcare systems. Although decision-making regarding adult vaccination is complex and influenced by psychological and personal factors, addressing practical or logistical issues related to immunization plans can facilitate higher vaccination coverage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Vaccinations represent a key public health measure that has substantially contributed to the decrease in mortality and morbidity from several infectious diseases (Andre et al. 2008).

The success of vaccination programs is highly dependent on the vaccination coverage achieved nationally and globally. However, public skepticism toward vaccination has resulted in the minimum vaccination threshold not being met, resulting in several disease outbreaks, such as measles and diphtheria, in recent decades (Cadeddu et al. 2020).

The current context of the COVID-19 pandemic might be an opportunity to identify and implement actions that could have a lasting impact on vaccination coverage, ultimately preventing outbreaks of pandemics and saving lives (Stöckeler et al. 2021).

Adult vaccinations are a fundamental pillar of any preventive health strategy, dramatically reducing the burden on an overburdened acute health system, with surprising cost savings for all levels of government (De Gomensoro et al. 2018).

It is critical to protect both adults, especially women in childbearing age, from diseases including rubella, and also newborns from congenital rubella syndrome, as well as measles, hepatitis B, pneumococcal disease, influenza, and cancers and diseases caused by the human papilloma virus (HPV) (Vojtek et al. 2018).

Current adult vaccine coverage is lower than target vaccination rates in most developed countries; consequently, vaccine preventable diseases continue to represent a substantial burden on health and healthcare resources, especially in older individual (De Gomensoro et al. 2018).

Adults have far fewer vaccinations recommended in the vaccination schedules with respect to other group populations, in addition to reduced funding for these vaccinations, few registries for tracking and recall, and fewer incentives in place with significant differences all over the world (Johnson et al. 2008).

For instance, the USA, Australia, and Canada have on average the highest coverage rates for vaccinations among adults, perhaps attributable to a greater number of institutional guidelines, registries and delivery systems (Williams et al. 2015).

Countries with less comprehensive vaccination programs, such as India and China, have very few recommended vaccines in the adult cluster and lower vaccination coverage rates (Wang et al. 2022).

Also in the European context, the adult vaccination offer is not homogeneous and an increasing number of countries, such as Germany, France, United Kingdom (UK), Italy, Sweden, and Spain show very different vaccination coverage rates (Kanitz et al. 2012).

The aim of the present work is to analyze existing strategies and policies used for adult vaccination in seven countries of the European region: UK and Sweden for Northern Europe; Germany and France for Central Europe; Italy and Spain for Southern Europe; Romania for Eastern Europe. These countries represent different geographical regions of the European area and have different vaccination policies and practices, also in relation to their different health systems and cultures.

Methods

This systematic review is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al. 2021). The protocol of this systematic review has been included in an internal report of the project (Online Resource 1).

Search strategy

Data sources used were PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science. Each electronic database was searched to identify relevant articles published in English, French, Spanish and Italian language. Since in a preliminary analysis the documents published before 2011 were found to be excessively dated, documents published from 01/01/2011 to 01/01/2023 were included.

The search string was developed consisting of the following keywords “adult vaccinations,” “healthy adults,” “adult immunization,” “schedule,” “European countries,” “strengths,” “weaknesses,” “barriers,” and “management.” The full search string is available in the Online Resource 2.

Eligibility criteria

The search question and the eligibility criteria for inclusion in the systematic review were developed according to the PICOS framework.

-

P (population) – Healthy adult populations (aged 18–64) in the selected European Countries (France, Italy, Spain, Germany, UK, Sweden, and Romania);

-

I (intervention) – Vaccination/immunization schedules/plan available;

-

C (comparator) – There is not a comparator applicable for the studies in this systematic review;

-

O (outcome) – Weakness and strengths of the vaccination plans

-

S (study type) – Either quantitative and qualitative studies reporting primary/secondary data were included.

Based on the PICOS developed for this systematic review, studies assessing weaknesses or strengths factors, facilitators and barriers related to the adult vaccination schedules/plans in the selected European countries were considered eligible.

Only primary studies were used for the data extraction process of this systematic review, while reviews (narrative, sco**, or systematic), commentaries and conference abstracts were excluded.

Study selection

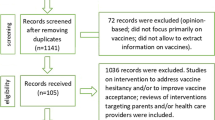

The identified articles from all the databases were uploaded to RAYYAN software (Rayyan Systems 2023) and the duplicates were removed. Four researchers (CC; TEL; AP; ST) independently performed the initial step of screening based on title and abstracts. As a second step, five independent researchers (CC; TEL; GSL; AP; ST) carefully read the articles with full texts available to decide upon the final articles to be included in the systematic review. Articles satisfying the eligibility criteria were selected for inclusion in the systematic review. Reasons for exclusion of full texts were recorded and were reported in the PRISMA flow chart (Fig. 1). The reference lists of the included articles were carefully hand-searched to retrieve additional eligible articles. Any discrepancies in the screening process and study selection were resolved by consulting a sixth researcher (ChC).

Data extraction and synthesis

Five researchers (CC; TEL; GSL; AP; ST) independently extracted from each article the following data:

-

Study identification (first author, year of publication).

-

Study characteristics (country, study design, population, study size).

-

Information related to the vaccination plan/schedule reported (type, age groups).

-

Barriers and success factors of the vaccination plan.

Any discrepancies in the data extraction process were resolved through discussion with a sixth author (ChC).

We performed a synthetic descriptive analysis of the studies according to the area of contextual factors.

Quality assessment

As the selected studies were all cross sectional, the Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS) (Downes et al. 2016) was used to assess the methodological quality of the included papers (questions of the AXIS tool available in the Online Resource 3).

Two independent researchers (AP and ST) evaluated each article, and any disagreements were resolved through group discussion.

Results

Results of the search strategy

A total of 10,536 articles were found from the three databases. Subsequently, 983 duplicates were removed and the remaining 9553 articles were screened by title and abstract. Overall, 230 papers were considered suitable for inclusion according to the eligibility criteria and were read in full text. Of these, 23 articles were not retrieved, 131 had a wrong outcome (not considering the strengths or weaknesses of vaccination plans), 32 considered a wrong population, 21 were in a language different from English, Italian, Spanish, or French and 14 had a wrong study design. Of these, nine articles were finally selected for inclusion in this systematic review. All of these articles had a cross-sectional study design. The selection process is reported in Fig. 1.

Results of the quality assessment

All the nine articles were evaluated as of “good quality.” None of the selected papers had a scarce or moderate quality.

The objectives of the study (question 1), the sample size (question 3), the reference population (question 4), the results presentation (question 16), the discussion and conclusions (question 17) were adequately described and the study design (question 2) was appropriate for all nine studies. The population sample (question 5) and the selection process (question 6) were always representative. On the other hand, only two of the studies reported the measures undertaken to address and categorize the non-responders (question 7). For some of the studies (5 out of 9), the response rate raised concerns about non-response bias (question 13). Furthermore, 7 out of 9 articles clearly discussed the limitations emerging from their studies (question 18) and 9 articles met the quality criteria about methods reproducibility (question 11).

Regarding conflict of interests and ethical reviews (questions 19 and 20), funding sources or conflicts of interest in three studies may have an impact on authors’ interpretation of the results. Five studies indicated they had ethical approval or consent of the participants. Two studies did not provide information on ethical clearance or whether they obtained consent of the survey participants.

Characteristics of the included studies

The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in the data extraction table, available in the Online Resource 4. A high percentage (4 studies, 45%) of the included studies took into account several EU/EEA states at the same time. One study (11%) was conducted in Italy; three studies (33%) in the UK; one study was conducted in Spain. All the included articles were published from 2011 to 2022. The vaccines taken into account in the included papers were influenza vaccine (5 studies); pertussis vaccine (2 studies); HPV vaccine (one study); pneumococcal vaccine (one study); several vaccines at the same time (2 studies).

The included studies investigated the vaccination schedules offered to the adult population (2 studies); the knowledge, attitudes and beliefs of healthcare professionals (4 studies); vaccination in specific groups of the adult population (i.e., migrants, 1 study; pregnant women, 2 studies).

Barriers and enablers for adult vaccination

We found that the main barriers or enablers for adult immunization, excluding personal beliefs toward vaccination (which were not analyzed in this systematic review), could be divided into three categories: financial factors; logistic factors; factors related to healthcare professionals.

Financial factors

Financial aspects may play a significant role in vaccine uptake. Most of the recommended vaccines have a public or private source of funding in the seven selected countries. A small minority of recommended vaccines, for instance the HPV vaccine, do not have a funding mechanism and the cost of these vaccines could represent a barrier to vaccine uptake. In this regard, lowering the costs of these types of vaccinations increases vaccine uptake, and an effective funding mechanism should be part of a comprehensive immunization strategy (Wu et al. 2013). On the opposite side, a European survey that investigated physicians’ attitudes toward pneumococcal vaccination showed that doubts regarding the cost of vaccination were low on the list of reasons against vaccination (Lode et al. 2013). As regards the population of adult migrants, a barrier that has been shown to hinder adult vaccination uptake is the inability to pay. While child migrants with uncertain vaccination status are in most countries re-vaccinated for free, adults may be charged for vaccination, which may discourage them from seeking vaccination. For this reason, most experts agreed that costs of vaccinations for migrants should be covered by national organizations and healthcare systems (Hargreaves et al. 2018).

Logistic factors

Practical aspects related to the organization and planning of the vaccination campaigns can influence the vaccination provision by healthcare professionals and the vaccination uptake by patients.

For instance, having a lead member for arranging the influenza vaccination campaign was associated with a higher influenza vaccine uptake in the <65 age group. At the same time, nominating a staff member with responsibility for identifying eligible patients was associated with increased uptake of the influenza vaccine in older age groups but not in under 65 (Dexter et al. 2012).

Appropriate computer programs to identify eligible or at-risk patients can be enablers of vaccination campaigns. Programs for identifying eligible patients are usually issued by the software providers. Modifying the IT supplier’s standard search or creating a separate in-house search was associated with significantly higher flu vaccine uptake rates for patients aged 65+ years than using an unmodified IT supplier’s search. A similar trend for under 65s did not reach statistical significance, perhaps due to insufficient power (Dexter et al. 2012).

Similarly, computer systems that identify patients who have not been vaccinated, and underline this information within the clinical notes, may also help improve vaccination rates by allowing primary care physicians to promote pneumococcal vaccination at each patient visit (Lode et al. 2013).

With regard to the methods of reaching the patients, using personal invitations, either alone or in combination with general publicity, was associated with higher rates of influenza vaccine uptake. More specifically, using both letters and telephone calls was not associated with significantly different vaccination rates than using either letters or phone calls alone (Dexter et al. 2012).

In a survey conducted among maternal care providers in the Catalonia region, Spain, an additional strategy to reach pregnant women was proposed: to include vaccine recommendations in the pregnancy booklet (an official booklet which comprises all medical check-ups during pregnancy), since the recommendation for influenza or pertussis vaccination is not mentioned in this booklet (Vilca et al. 2018).

With reference to vaccination against pertussis and influenza during pregnancy in an antenatal vaccination clinic at a tertiary hospital in the UK, convenience was the most important factor that encouraged uptake of vaccines at the vaccination clinic. The efficiency of the service was also an incentivizing factor. Nevertheless, women who were interviewed suggested increasing availability of appointments outside working hours to improve the service. In fact, vaccination at General Practitioner surgeries, as opposed to the vaccination at the antenatal vaccination clinic, has the benefits of providing vaccination on Saturdays and having free parking, while vaccination at work meant women did not have to travel (Ralph et al. 2022).

A study on pandemic influenza vaccination policies for pregnant women found that the decision to use vaccination centers instead of general practitioners for vaccination may have lowered the uptake of vaccination in some countries, such as France (Luteijn et al. 2011).

Considering that a barrier which has been shown to hinder migrants’ adult vaccination uptake in general is lack of coordination, most EU-experts agree that vaccination should be offered primarily at the point of entry or at a holding level (i.e., in reception centers, migrant camps, and detention centers) (Hargreaves et al. 2018).

While many of the included studied showed that opening times can be a barrier to vaccine uptake, a study investigating the strategies to increase influenza vaccination rates in the UK found that offering vaccinations at weekends, or before 8:00 or after 18:00, was not associated with a significant difference in the vaccination uptake rates achieved (Dexter et al. 2012).

Logistical issues were considered a barrier also in the viewpoint of a sample of midwives in the UK: 11% of respondents stated they had not received the seasonal influenza vaccine because vaccination was only offered at inconvenient times or they simply did not have time to attend a vaccination session. They suggested some strategies to boost uptake, such as providing access to information and evidence of the benefits of vaccination, effectively publicizing workplace vaccination, making vaccination available at more convenient times and places and where appropriate, providing mobile vaccinators (Ishola et al. 2013).

According to a sample of Italian general practitioners, useful actions to increase adherence to HPV vaccination practices were educational campaigns in the media (65.4%), school vaccination programs (48.8%), counseling courses for health workers (37.8%), creation of an “HPV space” within websites used by young people (37.3%), informative material (37.3%), and dedicated websites (19.7%) (Signorelli et al. 2014).

Factors related to healthcare professionals

Healthcare professionals (HCPs) can be key enablers to improve vaccination uptake, by encouraging vaccination and by reassuring the patients about vaccine safety and adverse effects. One of the papers included (Lode et al. 2013) showed that one of the main enablers of pneumococcal vaccination was the recommendation from a healthcare professional. Consequently, lack of physician recommendation or vaccine awareness can be barriers toward pneumococcal vaccination. In this regard, the main factors leading to a physician sometimes not recommending pneumococcal vaccination were that pneumococcal vaccination concerns only a subgroup of patients, the physician’s mind-set (i.e., vaccination is not at the top of the physician’s mind), and lack of time.

The recommendation from the HCPs was also pivotal in decision-making regarding pertussis and influenza vaccination during pregnancy (Ralph et al. 2022). Many women participating in this interview who did not receive the influenza vaccine were unaware of the recommendations for receipt during pregnancy due to lack of HCPs recommendation.

Another factor that can influence vaccine uptake is the provision of vaccination by HCPs other than doctors. A study conducted in UK general practice demonstrated that practices where community midwives were active in administering flu vaccinations to pregnant women had significantly higher uptake rates (Dexter et al. 2012). Similarly, vaccination rates of pneumococcal vaccines can be improved by nurse-led programs (Lode et al. 2013). In a study conducted in an antenatal vaccination clinic at a tertiary hospital in the UK, midwife endorsement, good relationship, and trust in the information given to women by their midwives encouraged vaccination among the women who were interviewed (Ralph et al. 2022). One reason for high vaccine uptake in the vaccination clinic reported in this study may be the additional contact with the vaccination team. In fact, the most common suggestion for improvement from the women’s point of view was to increase information provision. Many women felt that written information was not detailed enough, and that verbal discussion by midwives at booking appointments was needed to reinforce written information (Ralph et al. 2022).

Discussion

Our systematic review reports existing strategies and policies used for adult vaccination and it is the first one to summarize the main strength factors and barriers of immunization plans, focusing on some representative countries of the European region. Previous reviews on vaccination enablers or barriers have not addressed the practical issues influencing the vaccine uptake, nor have they focused on the policies for adult vaccination. Furthermore, previous reviews mainly analyzed data from North America, while we decided to concentrate on the factors that are peculiar to the countries of the European region.

Each of the nine included studies reported on a limited range of barriers or enablers relevant to a specific population, setting or vaccine. We found that financial factors (cost of vaccines, funding mechanisms, etc.), logistic factors (convenience, opening times, etc.), and factors related to Healthcare Professionals (recommendations, provision by different categories of HCPs, etc.) all play a part as enablers or barriers to adult vaccination in these countries.

Logistic factors are the most consistent and relatable determinants of vaccine uptake in all seven countries considered. Vaccine uptake can be influenced by practical considerations, which can be common across vaccines against different diseases or can be peculiar to one vaccine more than another. For instance, the organization of healthcare facilities, the use of appropriate software to recognize eligible patients (Dexter et al. 2012; Lode et al. 2013) or of personal reminders (Vilca et al. 2018) can determine the success of the vaccination campaign. Convenience factors, such as location and time of the vaccination facilities, can also play a role as barriers or enablers of vaccination uptake (Ralph et al. 2022; Luteijn et al. 2011; Hargreaves et al. 2018; Dexter et al. 2012; Ishola et al. 2013). In this context, proposed strategies are to arrange the vaccination facilities near to places where people work or live and to operate outside normal working hours (Siciliani et al. 2020).

Accessibility can also be improved by allowing different categories of healthcare professionals to take part in the vaccination campaigns. In different countries of the European region, in fact, vaccination administration is not permitted by pharmacists, nurses, midwives, and other healthcare professionals, with some exceptions such as Italy with pharmacists. In addition, the involvement of healthcare professionals other than doctors could foster vaccination in special categories of patients, for instance, midwives with pregnant women. Since physicians’ recommendation is an important factor influencing vaccination (Remschmidt et al. 2014; Ralph et al. 2022; Signorelli et al. 2014; Bödeker et al. 2014; Lode et al. 2013), the support of specialists who already take care of the patients (gynecologists and midwives for pregnant women; diabetologists for diabetics; etc) is also needed.

Finally, we found that where vaccines are not free of charge (e.g., HPV in some countries), costs remain a substantial barrier to vaccine uptake. Expanding the range of vaccines provided free of charge can be cost-effective and cost-saving and can help to achieve higher vaccination coverage (De Waure et al. 2012). This study should be read in the light of some limitations. While analyzing the studies, we found that there is scarce literature on this topic and many available documents are in the native language. This makes comparison between countries difficult and does not allow the sharing and implementation of best practices throughout the countries of the European region. In addition, each country has its own peculiarities, with different characteristics in the health systems organization and functioning. In Italy, for instance, the organization of healthcare varies from region to region, with regional authorities planning and organizing the practical aspects of vaccination campaigns independently (Ferre et al. 2014). These regional differences could lead to regional gaps in the barriers and strengths factors affecting vaccination, with some regions ensuring more accessible and convenient vaccination campaigns and others facing difficulties in the implementation of them. In addition, we only took into account practical barriers and strength factors toward vaccination, while scientific literature has widely demonstrated that the most influential factors affecting vaccination uptake are individual decision-making processes, the lack of easily accessible information for citizens, and vaccine literacy (Dubé et al. 2013). Vaccine literacy – the ability to find, understand and judge immunization-related information to make appropriate immunization decisions – is not homogeneous among the population (Cadeddu et al. 2022), thus leading to inequalities in vaccination coverage.

Providing clear and accessible information to citizens is something that institutions and stakeholders from the European region can all work together to improve. Accessibility of information about vaccination should be enhanced not only with regard to vaccine coverages, efficacy, and safety but also to functioning of vaccination services, vaccination schedules, and organization of vaccination campaigns. A suggested strategy to achieve an improvement of vaccine accessibility throughout the European region could be a common platform held by the main institutions working in the public health field – for example, the ECDC (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control) – proposing contents focused on the practical and logistical factors related to vaccination in the countries of this area. Such a platform, similar to the one used for infectious diseases surveillance (Surveillance Atlas of Infectious Diseases n.d.), could be a facilitating means to enable data sharing of best practices regarding the organization of vaccination services from one country to another. The improvement of the accessibility of these types of information could boost vaccine uptake in the category of population who intentionally delay vaccination because their decision is influenced by the quality and convenience of the vaccination services (Dubé et al. 2013).

Conclusion

In conclusion, substantial improvement in adult vaccination is urgently necessary to substantially reduce the burden of vaccine-preventable diseases on healthcare systems, not only for COVID-19. Although decision-making regarding adult vaccination is complex and influenced by several personal and psychological factors, addressing practical or logistical issues related to immunization plans can contribute to achieving a higher vaccination coverage.

This systematic review provides a comprehensive summary of existing strategies and policies of adult immunization policies in seven countries of the European region, and underlines the main practical barriers and strength factors of the vaccination plans in these countries. The evidence from this systematic review can be beneficial for stakeholders and policy-makers who discuss and implement vaccination strategies.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Andre F, Booy R, Bock H, Clemens J, Datta S, John T, Lee B, Lolekha S, Peltola H, Ruff T, Santosham M, Schmitt H (2008) Vaccination greatly reduces disease, disability, death and inequity worldwide. Bull World Health Organiz 86(2):140–146. https://doi.org/10.2471/blt.07.040089

Bödeker B, Walter D, Reiter S, Wichmann O (2014) Cross-sectional study on factors associated with influenza vaccine uptake and pertussis vaccination status among pregnant women in Germany. Vaccine 32(33):4131–4139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.06.007

Cadeddu C, Daugbjerg S, Ricciardi W, Rosano A (2020) Beliefs towards vaccination and trust in the scientific community in Italy. Vaccine 38(42):6609–6617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.07.076

Cadeddu C, Regazzi L, Bonaccorsi G, Rosano A, Unim B, Griebler R, Link T, De Castro P, D’Elia R, Mastrilli V, Palmieri L (2022) The determinants of vaccine literacy in the Italian population: results from the Health Literacy Survey 2019. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(8):4429. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084429

De Gomensoro E, Del Giudice G, Doherty TM (2018) Challenges in adult vaccination. Annals Med 50(3):181–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2017.1417632

De Waure C, Veneziano MA, Cadeddu C, Capizzi S, Specchia ML, Capri S, Ricciardi W (2012) Economic value of influenza vaccination. Human Vaccines Immunotherapeutics 8(1):119–129. https://doi.org/10.4161/hv.8.1.18420

Dexter LJ, Teare MD, Dexter M, Siriwardena AN, Read RC (2012) Strategies to increase influenza vaccination rates: outcomes of a nationwide cross-sectional survey of UK general practice. BMJ Open 2(3):e000851. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000851

Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, Dean RS (2016) Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open 6(12):e011458. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011458

Dubé E, Laberge C, Guay M, Bramadat P, Roy R, Bettinger JA (2013) Vaccine hesitancy. Human Vaccines Immunotherapeutics 9(8):1763–1773. https://doi.org/10.4161/hv.24657

Ferre F, de Belvis AG, Valerio L, Longhi S, Lazzari A, Fattore G, Ricciardi W, Maresso A (2014) Italy: health system review. Health Syst Trans 16(4):1–168

Hargreaves S, Nellums LB, Ravensbergen SJ, Friedland JS, Stienstra Y (2018) Divergent approaches in the vaccination of recently arrived migrants to Europe: a survey of national experts from 32 countries, 2017. Eurosurveillance 23(41). https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.es.2018.23.41.1700772

Ishola D, Permalloo N, Cordery R, Anderson S (2013) Midwives’ influenza vaccine uptake and their views on vaccination of pregnant women. J Public Health 35(4):570–577. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fds109

Johnson DR, Nichol KL, Lipczynski K (2008) Barriers to adult immunization. Am J Med 121(7):S28–S35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.05.005

Kanitz EE, Wu LA, Giambi C, Strikas RA, Levy-Bruhl D, Stefanoff P, Mereckiene J, Appelgren E, D’Ancona F (2012) Variation in adult vaccination policies across Europe: an overview from VENICE network on vaccine recommendations, funding and coverage. Vaccine 30(35):5222–5228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.06.012

Lode H, Ludwig E, Kassianos G (2013) Pneumococcal infection — low awareness as a potential barrier to vaccination: results of a European survey. Advances Ther 30(4):387–405. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-013-0025-4

Luteijn JM, Dolk H, Marnoch GJ (2011) Differences in pandemic influenza vaccination policies for pregnant women in Europe. BMC Public Health 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-819

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S et al (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Ralph KM, Dorey RB, Rowe R, Jones CE (2022) Improving uptake of vaccines in pregnancy: a service evaluation of an antenatal vaccination clinic at a tertiary hospital in the UK. Midwifery 105:103222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2021.103222

Rayyan Systems (2023) – Intelligent Systematic Review. Rayyan. https://www.rayyan.ai. Accessed 03/02/2023

Remschmidt C, Walter D, Schmich P, Wetzstein M, Deleré Y, Wichmann O (2014) Knowledge, attitude, and uptake related to human papillomavirus vaccination among young women in Germany recruited via a social media site. Human Vaccines Immunotherapeutics 10(9):2527–2535. https://doi.org/10.4161/21645515.2014.970920

Siciliani L, Wild C, McKee M, Kringos D, Barry MM, Barros PP, De Maeseneer J, Murauskiene L, Ricciardi W (2020) Strengthening vaccination programmes and health systems in the European Union: A framework for action. Health Policy 124(5):511–518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2020.02.015

Signorelli C, Odone A, Pezzetti F, Spagnoli FM, Visciarelli S, Ferrari AJL, Camia P, Latini C, Ciorba V, Agodi A, Barchitta M, Scotti S, Misericordia P, Pasquarella C (2014) Human Papillomavirus infection and vaccination: knowledge and attitudes of Italian general practitioners. Epidemiologia E Prevenzione 38(6 Suppl 2):88–92

Stöckeler AM, Schuster P, Zimmermann M, Hanses F (2021) Influenza vaccination coverage among emergency department personnel is associated with perception of vaccination and side effects, vaccination availability on site and the COVID-19 pandemic. PLOS One 16(11):e0260213. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0260213

Surveillance Atlas of Infectious Diseases (n.d.) http://atlas.ecdc.europa.eu/public/index.aspx. Accessed 03/04/2023

Vilca LM, Martínez C, Burballa M, Campins M (2018) Maternal care providers’ barriers regarding influenza and pertussis vaccination during pregnancy in Catalonia, Spain. Maternal Child Health J 22(7):1016–1024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-018-2481-6

Vojtek I, Dieussaert I, Doherty TM, Franck V, Hanssens L, Miller J, Bekkat-Berkani R, Kandeil W, Prado-Cohrs D, Vyse A (2018) Maternal immunization: where are we now and how to move forward? Annals Med 50(3):193–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2017.1421320

Wang J, Liu CH, Ma Y, Zhu X, Luo L, Ji Y, Tang H (2022) Two-year immune effect differences between the 0–1–2-month and 0–1–6-month HBV vaccination schedule in adults. BMC Infect Dis 22(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-022-07151-6

Williams WW, Lu P, O’Halloran A, Bridges CB, Kim DH, Pilishvili T, Hales CM, Markowitz LE (2015) Vaccination coverage among adults, excluding influenza vaccination - United States, 2013. Morbidity Mortal Weekly Report 64(4):95–102

Wu LA, Kanitz E, Crumly J, D’Ancona F, Strikas RA (2013) Adult immunization policies in advanced economies: vaccination recommendations, financing, and vaccination coverage. Int J Public Health 58(6):865–874. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-012-0438-x

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. This work was unconditionally supported by GlaxoSmithKline.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: TEL, ChC. Literature search and data analysis: TEL, GSL, ST, AP, CC. Quality assessment: ST, AP. Draft preparation and editing: TEL, GSL, ST. Supervision: ChC.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for this type of study is not required.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lanza, T.E., Lombardi, G.S., Tumelero, S. et al. Barriers and strength factors of adult immunization plans in seven countries of the European region. J Public Health (Berl.) (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-023-01986-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-023-01986-2