Abstract

Gender-specific differences in the treatment of epilepsy are a continuous challenge in the choice of treatment. Earlier studies on antiseizure medication often only or predominantly included male patients. The establishment of pregnancy registries including girls and women of childbearing age with epilepsy in Europe and North America have given many more insights into the side effects as well the teratogenic effects of antiseizure medications (ASM) on their children. The SANAD II study provided essential new data on the clinical effectiveness as well as the cost-effectiveness of the most frequently used antiseizure medications in focal, generalized and unclassifiable epilepsies. These results were taken into account for the new revised guidelines of the German, Austrian and Swiss neurological societies on epilepsy treatment in adults; however, several aspects regarding the gender-specific choice of antiseizure medication remain controversial, especially the use of valproate in generalized epilepsy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The results of the first SANAD (Standard and New Antiepileptic Drugs) study were published in 2007. In a randomized controlled trial, the standard drug at the time, carbamazepine (CBZ), was compared with the then newer antiseizure medications lamotrigine (LTG), topiramate (TPM), gabapentin (GBP), and oxcarbazepine (OXC) in patients with focal epilepsy. Lamotrigine was found to be more effective and cost-effective in focal epilepsy than CBZ or the other antiseizure drugs, which were newer by the standards of the time. In this regard, LTG was significantly better than CBZ, GBP, and TPM in terms of time to treatment discontinuation due to lack of efficacy or intolerable side effects and showed a nonsignificant advantage over OXC, the assessability of which was limited owing to small case numbers when the drug was subsequently considered [6].

In the second part of the study, the then first-line agent, valproate (VPA), was investigated in patients with generalized and unclassifiable epilepsy in comparison to LTG and TPM. Here, VPA was found to be better tolerated than TPM and more effective than LTG and was therefore recommended as the first-line agent, although it was noted that due to the side effects of VPA when used during pregnancy, the benefits in terms of seizure control in women of childbearing age should be reconsidered [7]. The results of these two initial SANAD studies found their way into the German, Austrian, and Swiss neurological society guidelines, which were still valid until recently [2].

However, a major limitation of the SANAD I trials for implementation in guidelines and thus into daily clinical practice was that no comparison was made with levetiracetam (LEV). However, LEV is recommended as the first-line agent, along with LTG, for focal epilepsy according to the guidelines of the German, Austrian, and Swiss neurological societies and, as such, is widely used.

In addition, LEV has also been increasingly used in generalized and unclassifiable epilepsy in recent years—particularly in women of childbearing age. The only slight, but statistically nonsignificant, superiority of VPA over LEV presented in the KOMET study [12] needs to be included here. However, one must bear in mind that LEV is in fact approved for idiopathic generalized epilepsy only as an additional treatment, with minor country-specific differences.

The question now is whether the SANAD II studies published in 2021 can fill this information gap.

Results of the SANAD II study

Like the SANAD I study, the SANAD II study comprises two study parts: On the one hand, patients with newly diagnosed focal epilepsy and on the other, patients with newly diagnosed generalized or unclassifiable epilepsy were studied. LTG as the “winner” of the SANAD I trial for focal epilepsy was compared with LEV and zonisamide (ZNS), while VPA as the winner of the SANAD I trial for generalized and unclassifiable epilepsy was compared with LEV [8, 9].

Unexpected outcome: levetiracetam inferior to lamotrigine in focal epilepsy

In the study arm for newly diagnosed focal epilepsy, 990 patients aged ≥ 5 years were included from May 2013 to June 2017 and followed up for 2 years [8]. Patients were randomly assigned to therapy with LTG (n = 330), LEV (n = 332), or ZNS (n = 328). All patients were included in the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis; for the per-protocol (PP) analysis, patients with significant protocol deviations and patients in whom the diagnosis of epilepsy could not be confirmed in the further course were excluded, meaning that ultimately 324 patients with LTG, 320 patients with LEV, and 315 patients with ZNS were included in the PP analysis. A hazard ratio (HR) of 1.329, corresponding to an absolute difference of 10%, was set as the noninferiority limit for the primary outcome parameter, time to 12-month seizure remission. This threshold is recommended by the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) for evidence of equivalence or noninferiority. In the ITT analysis for the primary outcome parameter—time to 12-month seizure remission—LEV did not meet the noninferiority criteria compared with LTG (HR: 1.18; 97.5% confidence interval [CI]: 0.95–1.47; CI included the predefined noninferiority limit of 1.329), whereas ZNS met the noninferiority criteria compared with LTG (HR: 1.03; 97.5% CI: 0.83–1.28). In the PP analysis, time to 12-month seizure remission was significantly better for LTG than for LEV (HR: 1.32; 97.5% CI: 1.05–1.66) and for ZNS (HR: 1.37; 97.5% CI: 1.08–1.73). By contrast, for the secondary outcome parameter regarding seizure control—time to 24-month seizure remission—there was no significant difference between the substances. For one of the secondary outcome parameters regarding treatment discontinuation, namely, time to treatment discontinuation for any cause (inadequate seizure control and/or unacceptable side effects), LTG was significantly better than LEV and ZNS. Treatment failure occurred significantly more often for both LEV and ZNS than for LTG due to side effects, whereas no significant difference was found with respect to inadequate seizure control. Side effects were reported by 33% of patients on LTG, by 44% on LEV, and by 45% on ZNS. The main difference was in psychiatric side effects (13% under LTG, 30% under LEV, 23% under ZNS). The cost–benefit analysis also showed a significant benefit for LTG. The authors concluded that LEV and ZNS cannot be recommended as first-line agents in the treatment of newly diagnosed focal epilepsy, that LTG should be the sole first-line agent, and that it should be used as the standard of care or reference drug for future studies [8]. One drawback of the SANAD II trial, in addition to the lack of blinding, is doubtless that other newer antiseizure medications approved for focal epilepsy in monotherapy, particularly lacosamide (LCM), were not included.

SANAD II challenges: valproate versus levetiracetam

The second part of the SANAD II trial compared VPA and LEV in patients with newly diagnosed generalized and unclassifiable epilepsy. The phase IV multicenter noninferiority trial enrolled a total of 520 patients aged ≥ 5 years with ≥ two unprovoked seizures between 2013 and 2016 and followed them up for 2 years [9]. After randomization, 260 participants received LEV and 260 VPA at an age-adjusted dose. The primary endpoint was noninferiority of LEV versus VPA in the period to remission at 12 months. Patients were randomly assigned to treatment with VPA (n = 260) or LEV (n = 260). All patients were included in the ITT analysis, and 255 patients with VPA and 254 patients with LEV remained in the PP analysis (patients with significant protocol deviations and patients in whom the diagnosis of epilepsy could not be confirmed at further follow-up were excluded for the PP analysis). The median age of the study participants was 13.9 years (range: 5.0–94.4 years); thus, most patients were children and adolescents; 65% were men, 35% were women, 397 (76.3%) had generalized epilepsy, and 123 (23.7%) had nonclassifiable epilepsy. A hazard ratio of 1.314 corresponding to an absolute difference of 10% was set as the noninferiority limit for the primary outcome parameter—time to 12-month seizure remission. In the ITT analysis for the primary outcome parameter, LEV did not achieve the noninferiority criteria compared with VPA (HR: 1.19; 95% CI: 0.96–1.47; the CI included the predefined noninferiority limit of 1.314). Valproate was significantly superior to LEV in the PP analysis. In a post hoc subgroup analysis, there was a clear advantage for VPA in patients with generalized epilepsy in whom the precise idiopathic generalized epilepsy syndrome remained unclear (e.g., patients with generalized tonic–clonic seizures and generalized spike-wave discharges on EEG), but not for absence epilepsy nor for nonclassifiable epilepsy. Valproate was also significantly superior to LEV for the secondary outcome parameter for seizure control—time to 24-month remission (HR: 1.43; 95% CI: 1.06–1.92). Treatment discontinuations for any reason (inadequate seizure control and/or unacceptable side effects) were significantly less frequent with VPA than with LEV, with a significant advantage for VPA in terms of treatment discontinuations due to lack of efficacy, but no significant difference was detectable for treatment discontinuations due to side effects. Side effects were reported by 37% of patients on VPA and by 42% on LEV. Psychiatric side effects were more common under LEV (26% vs. 14%), while weight gain was more common under VPA (10% vs. 3%). The cost–benefit analysis showed a significant benefit for VPA.

The authors concluded that LEV was neither as clinically effective nor as cost-effective as VPA. This meant that the counseling of girls and women of childbearing age had to discuss even more carefully than previously whether VPA could be dispensed with [9].

In summary, the two SANAD II studies question the previously valid guideline recommendations of the German, Austrian, and Swiss neurological societies for the treatment of newly diagnosed epilepsy, especially focal epilepsy. Accordingly, a revision of these guidelines was undertaken, and the new guideline recommendations—S2k guideline on the treatment of epilepsy—were presented for the first time in a lecture on March 18, 2023, at the joint annual meeting of the German and Austrian Societies for Epileptology and the Swiss Epilepsy League. The final version will soon be available online [5].

What conclusions for gender-specific treatment should be drawn from the results of the SANAD II study?

In patients with focal epilepsy, the results of the SANAD II study once again confirmed LTG as the first-line agent. Previous data from pregnancy registries indicated at most only slightly increased teratogenicity in a dose-dependent manner when LTG was taken at a dose of > 325 mg/day at the time of conception. Although in routine clinical practice LEV is frequently prescribed for focal epilepsy, no doubt in part due to the option of faster dosing, LTG is probably still the more effective and cost-efficient form of treatment as the agent of first choice in men and women. It must also be noted here that the slow dose escalation required with LTG does not lead to an increased risk of seizures in this dose escalation phase compared to LEV. Thus, in the LaLiMo Trial, in which LTG and LEV were compared in the initial monotherapy of newly diagnosed focal and generalized epilepsy, no difference was seen between LTG and LEV with regard to seizure control in the first 6 weeks of treatment (= primary outcome parameter: [10]). Likewise in the SANAD II study, there was no difference in seizure control between LTG, LEV, and ZNS in the first weeks of treatment [8]. Thus, an initial bridging combination therapy with LEV and LTG cannot be recommended.

Lamotrigine has been confirmed as the first-line agent in focal epilepsy

Nevertheless, in clinical practice, LEV is increasingly used as the first-line medication for focal and generalized epilepsy. This choice is supported by the ILAE and the Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften e. V., AWMF) guideline 030/041 of 2017. A recent prospective study conducted by the Epilepsy Center Hessen, Germany, on the clinical reality in the initial treatment of focal epilepsy, presented at the German-speaking Tri-Country Conference, showed that LEV is used in the majority of patients (64%). A statistical comparative analysis is currently not yet possible in the study, which has been ongoing since 2018 [3]. However, SANAD II also showed there was no longer a difference between LEV and LTG for 24-month remission in this treatment group. Since neither drug has yet shown increased teratogenicity or developmental delay in children with intrauterine exposure, the choice between LEV and LTG is not influenced by the sex of the patient.

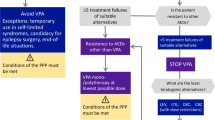

Even more exciting are the implications of the SANAD II trial results in generalized epilepsy. There is certainly no doubt among experts that VPA is the most effective drug in generalized as well as in difficult-to-classify epilepsy. This was also the general consensus even before the publication of the SANAD II results. Nevertheless, in routine clinical practice, LEV is very often prescribed for women of childbearing age even for generalized or difficult-to-classify epilepsy.

However, once the results of the SANAD II study are available, one will certainly need to discuss more intensively whether and under what circumstances a woman of childbearing age can or may also be deprived of the most effective treatment method. At the very least, despite the teratogenicity of VPA as well as its negative effects on cognitive development and the increased risk for autism spectrum disorders in children exposed to the drug during pregnancy [1], treatment with VPA must be discussed with the patient, and the efficacy of the treatment must be weighed against the side effects and especially the negative effects in each individual case. This is certainly only possible if the patients themselves are sufficiently informed about all positive and negative aspects. After all, the therapeutic goal remains freedom from seizures, and one should not lose sight of this.

Having said that, a 2021 European expert opinion published on the use of VPA in girls and women of childbearing age was that seizure-associated risks during pregnancy must be weighed against the teratogenicity-associated risks of VPA, but that, in general, VPA should not be used as a first-line medication in girls older than 10 years and women [11]. Also, the demonstrated increased teratogenicity due to VPA and its negative impact on the cognitive development of the unborn child have led the European Medicines Agency (EMA) to make a strong recommendation (EMA, 21 Nov 2014) to limit the use of VPA to cases where it is essential. In evaluating the various pregnancy registries, it appears that dosages above 650 mg/day should not be sought when VPA is essential. The form filled in annually by the specialist physician confirming that the patient has been provided with the information on risks should be completed.

The problem of the individual counseling situation has now become even more acute. It is not so easy to refuse patients—as is often the case—the most effective treatment virtually apodictically from the outset. As justiciable as teratogenic effects of VPA may rightly be if patients are uninformed of the risks, it is now quite conceivable with the availability of the SANAD II study that forensically relevant questions could be raised in the case of serious consequences of an obviously second-best epilepsy treatment (regardless of whether with LTG or LEV) that has omitted the use of VPA.

In men, on the other hand, the decision is much easier, since VPA is the drug of first choice for generalized and difficult-to-classify epilepsy. There are currently no known negative effects on a child conceived by a man receiving VPA treatment.

Valproate is the first-choice drug for men with generalized and difficult-to-classify epilepsy

However, in December 2022, the public health authorities in the United Kingdom, citing studies on the adverse effect of VPA on testicular size and sperm motility, also restricted the use of VPA in men under 55 years of age: The UK’s Commission on Human Medicines (CHM) recommends that no patient under the age of 55 years should be placed on VPA unless two specialists independently conclude that there is no other effective or tolerated treatment in the individual case [13].

At the recent Epilepsy Congress in Berlin, Germany, in March 2023, the new guidelines for the treatment of first seizures and adult-onset epilepsy were presented for the first time in a lecture, incorporating the results of the SANAD II study [5]. In summary, the gender-specific recommendations within these new guidelines are as follows.

New guidelines on focal epilepsy

For focal, new-onset epilepsy, LTG should be used as the first-line agent in monotherapy. If LTG is not an option, LCM or LEV should be used in monotherapy. If LCM, LTG, or LEV are not an option, other alternatives approved for monotherapy may be considered in monotherapy depending on individual circumstances.

New guidelines on generalized epilepsy

It is recommended that in men, as well as in women in whom conception can be excluded with a high degree of certainty, with genetic generalized epilepsy and predominantly myoclonic and tonic–clonic seizures, VPA be used as the first-line agent in monotherapy. If VPA is not considered as the first-line drug in these patients, LTG or LEV should be used. The safest method of contraception recommended for women with epilepsy on antiseizure medication (ASM) is the hormonal intrauterine device (IUD).

In women of childbearing age with genetic generalized epilepsy in whom conception cannot be ruled out, LTG or LEV should be used in monotherapy; this also applies to absence epilepsy.

New guidelines on unclassified epilepsy

In patients with unclassified epilepsy, LTG, LEV, or VPA should be used as first-line drugs in monotherapy—the latter only in men and in those women in whom conception can be ruled out with a high degree of certainty.

New guidelines on the treatment of women with epilepsy who wish to have children

For women with epilepsy who wish to have a child, ASM should be in the form of monotherapy.

In women with focal epilepsy who wish to have a child, LTG should be given at the lowest effective dose possible (not to exceed 325 mg/day before conception) or LEV. If LTG or LEV are not an option, OXC should be given at the lowest effective dose possible. If LTG, LEV, and OXC are not an option, the use of other alternatives approved for monotherapy may be considered on a case-by-case basis.

In women with genetic generalized or unclassified epilepsy who wish to have a child, LTG at the lowest effective dose possible (not to exceed 325 mg/day before conception) or LEV should be given as the first-line drug. Valproate may be considered only if other reasonable ASMs have not been effective or tolerated. The dose of VPA should not exceed 650 mg/day. To reduce the teratogenic risk of VPA, spreading the daily dose over three to four individual doses may be considered. Prior to and during pregnancy, detailed counseling should be provided by a certified specialty outpatient unit or specialist practice or by a certified epilepsy center.

The authors’ comments on the new guidelines

In addition to the recommendations of the European Medicines Agency (EMA), the new guidelines take into account in particular the results of the various European pregnancy registries. Critically, the authors note that the use of VPA is consistently excluded only in cases of pregnancy. On the other hand, they propose replacing “women wishing to become pregnant” with “girls and women of childbearing age,” thereby further restricting or making even more critical the indication for treatment with VPA in generalized or unclassified epilepsy. It is certainly welcome that LCM has been ranked as a possibility alongside LTG and LEV based on its favorable properties. However, it is regrettable and limiting that despite the undoubted benefits of LCM, no robust data on teratogenicity are available and the drug did not find its way into the SANAD II study. In a recent observational study conducted by the Pharmacovigilance and Consultation Center for Embryonic Toxicology at the Charité University Hospital Berlin, Germany, no evidence for an increased risk of major malformations or spontaneous abortions was found in 55 prospectively and 10 retrospectively analyzed pregnancies while using LCM [4].

Currently, the question arises as to whether the results of the SANAD II studies are really taken into account in clinical reality. Currently, several multicenter studies on treatment after initial diagnosis of both focal and generalized or difficult-to-classify epilepsy are ongoing in all German-speaking countries. Their results will hopefully provide us with additional valuable data in the coming years.

Practical conclusion

-

Gender differences in treatment choices pose an ongoing challenge in epilepsy care.

-

The SANAD (Standard and New Antiepileptic Drugs) II trial has yielded substantial new data on the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of the most commonly used antiseizure medications in both focal and generalized as well as unclassifiable epilepsy.

-

However, several issues remain problematic in drug selection, particularly with regard to the use of valproate in generalized epilepsy and in girls and women of childbearing age.

References

Bjørk MH, Zoega H, Leinonen MK, Cohen JM, Dreier JW, Furu K, Gilhus NE, Gissler M, Hálfdánarson Ó, Igland J, Sun Y, Tomson T, Alvestad S, Christensen J (2022) Association of prenatal exposure to Antiseizure medication with risk of autism and intellectual disability. JAMA Neurol 79(7):672–681

Elger, CE, Berkenfeld, R (geteilte Erstautorenschaft) et al (2017) S1-Leitlinie Erster epileptischer Anfall und Epilepsien im Erwachsenenalter. Online: www.dgn.org/leitlinien

Fuchs A, Weil JC, Linka L, Müller C, Krause K, Habermehl L, Knake S (2023) SANAD-II vs. klinische Realität

Hoeltzenbein M, Slimi S, Fietz AK, Stegherr R, Onken M, Beyersmann J et al (2023) Increasing use of newer antiseizure medication during pregnancy: An observational study with special focus on lacosamide. Seizure 107:107–113

Holtkamp M, Weber Y et al. (2023) S1-Leitlinien Erster epileptischer Anfall und Epilepsien im Erwachsenenalter. Präsentiert bei der gemeinsamen Jahrestagung der Deutschen und Österreichischen Gesellschaften für Epileptologie und der Schweizerischen Epilepsie-Liga am 18. März 2023in Berlin

Marson AG, Al-Kharusi AM, Alwaidh M et al (2007) The SANAD study of effectiveness of carbamazepine, gabapentin, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, or topiramate for treatment of partial epilepsy: an unblinded randomised controlled trial. Lancet 369:1000–1015

Marson AG, Al-Kharusi AM, Alwaidh M et al (2007) The SANAD study of effectiveness of valproate, lamotrigine, or topiramate for generalised and unclassifiable epilepsy: an unblinded randomised controlled trial. Lancet 369:1016–1026

Marson A, Burnside G, Appleton R et al (2021) The SANAD II study of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of levetiracetam, zonisamide, or lamotrigine for newly diagnosed focal epilepsy: an open-label, non-inferiority, multicentre, phase 4, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 397:1363–1374

Marson A, Burnside G, Appleton R et al (2021) The SANAD II study of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of valproate versus levetiracetam for newly diagnosed generalised and unclassifiable epilepsy: an open-label, non-inferiority, multicentre, phase 4, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 397:1375–1386

Rosenow F, Schade-Brittinger C, Burchardi N et al (2012) The LaLiMo Trial: lamotrigine compared with levetiracetam in the initial 26 weeks of monotherapy for focal and generalised epilepsy—an open-label, prospective, randomised controlled multicenter study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 83:1093–1098

Toledo M, Mostacci B, Bosak M, Jedrzejzak J, Thomas RH, Salas-Puig J, Biraben A, Schmitz B (2021) Expert opinion: use of valproate in girls and women of childbearing potential with epilepsy: recommendations and alternatives based on a review of the literature and clinical experience—a European perspective. J Neurol 268(8):2735–2748

Trinka E, Marson AG, Van Paesschen W, Kälviäinen R, Marovac J, Duncan B, Buyle S, Hallström Y, Hon P, Muscas GC, Newton M, Meencke HJ, Smith PE, Pohlmann-Eden B for the KOMET Study Group (2013) KOMET: an unblinded, randomised, two parallel-group, stratified trial comparing the effectiveness of levetiracetam with controlled-release carbamazepine and extended-release sodium valproate as monotherapy in patients with newly diagnosed epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 84(10):1138–1147

Update on MHRA review into safe use of valproate—GOV.UK (www.gov.uk) Government UK: 12 December 2022

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

B. Tettenborn has received honoraria from Eisai and Angelini in the past 5 years. C. Baumgartner received consulting/lecturing fees from Eisai, UCB, Jazz, Angelini, and Precisis in the past 5 years. B. Schmitz has received honoraria from Arvelle/Angelini, Desitin, Eisai, Precisis, Sanofi, and UCB-Pharma in the past 5 years. B. J. Steinhoff has received speaking honoraria from Al Jazeera, Angelini, Bial, Desitin, Eisai, GW, Hikma, Medscape, Tabuk, and UCB in the past 5 years.

For this article no studies with human participants or animals were performed by any of the authors. All studies mentioned were in accordance with the ethical standards indicated in each case.

The supplement containing this article is not sponsored by industry.

Additional information

Scan QR code & read article online

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tettenborn, B., Baumgartner, C., Schmitz, B. et al. Does SANAD II help with gender-specific problems in epilepsy treatment?—English Version. Clin Epileptol 36 (Suppl 2), 115–119 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10309-023-00626-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10309-023-00626-9