Abstract

Background

To obtain a pathologically negative proximal margin (PM) for gastric cancer with gross esophageal invasion (EI) or esophagogastric junction (EGJ) cancer, we should transect the esophagus beyond the proximal boundary of gross EI with a safety margin because of a discrepancy between the gross and pathological boundaries of cancer. However, recommendations regarding the esophageal resection length for these cancers have not been established.

Methods

Patients who underwent proximal or total gastrectomy for gastric cancer with gross EI or EGJ cancer were enrolled. A parameter ΔPM, which corresponded to the length of a discrepancy between the gross and pathological proximal boundary of the tumor, was evaluated. The maximum ΔPM, which corresponded to the minimum length ensuring a pathologically negative PM, was first determined in all patients. Then subgroup analyses according to factors associated with ΔPM ≥ 10 mm were performed to identify alternative maximum ΔPMs.

Results

A total of 289 patients with gastric cancer with gross EI or EGJ cancer were eligible and analyzed in this study. The maximum ΔPM was 25 mm. Clinical tumor (cTumor) size and growth and pathological types were independently associated with ΔPM ≥ 10 mm. In subgroup analyses, the maximum ΔPM was 15 mm for cTumor size ≤ 40 mm and superficial growth type. Furthermore, the maximum ΔPM was 20 mm in the expansive growth type.

Conclusions

Required esophageal resection lengths to ensure a pathologically negative PM for gastric cancer with gross EI or EGJ cancer are proposed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gastric cancer is the fifth most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer death worldwide, with approximately 1,089,000 new diagnoses and 768,000 deaths recorded each year [1]. Recently, the incidence of upper-third gastric cancer and esophagogastric junction (EGJ) cancer has increased in East Asian countries [2, 3]. Surgical resection is an indispensable treatment to cure such disease, but it is more technically demanding than surgery for middle to lower cancer [4, 5]. Even though the disease is dominantly located in the upper stomach, additional procedures around the lower esophagus are similarly integral in EGJ cancer when it grossly involves the esophagus.

Obtaining a pathologically negative margin is an essential issue in surgery with curative intent. A pathologically positive resection margin is associated with poor prognosis [6,7,8,9]. To obtain a pathologically negative margin for gastric cancer with gross esophageal invasion (EI) and EGJ cancer, we should transect the esophagus beyond the proximal boundary of gross EI in total gastrectomy (TG) or proximal gastrectomy (PG) with a safety margin because of a discrepancy between the gross and pathological boundaries of cancer [10].

Several guidelines for gastric cancer recommend different extents of resection margin in gastrectomy. The Japanese Gastric Cancer Treatment Guidelines (JGCTGs) suggest that a gross proximal margin (PM) of at least 2 cm should be obtained for T1, 3 cm for T2 or deeper (T2–4) tumors with expansive growth type (Exp), and 5 cm for infiltrative growth type (Inf) [11]. However, the recommendations do not refer to scientific evidence. Furthermore, not only the JGCTGs but also guidelines in other countries solely mention the safety margin in distal gastrectomy [11,12,13]. We recently published a study that revealed the minimum length of esophageal resection in TG for gastric cancer without gross EI [14]. However, no study has indicated the safety margin for gastric cancer with gross EI or EGJ cancer.

In gastric cancer with gross EI or EGJ cancer, obtaining a longer PM is more difficult than that in gastric cancer without gross EI because of the anatomical features of the esophagus. When a longer specimen of the esophagus is harvested to obtain a longer PM length, the esophagus is transected in the deeper and narrower space of the posterior mediastinum. Furthermore, in reconstruction, bringing up the jejunum or the remnant stomach and connecting it to the edge of the esophagus is also difficult whatever type of reconstruction is selected. Additionally, when the anastomosis has failed postoperatively, mediastinitis sometimes occurs and may be associated with lethal problems. Thus, identifying the minimum length of esophageal resection is particularly useful and important.

In this study, we evaluated the discrepancy between the clinical and pathological PM lengths of gastric cancer with gross EI or EGJ cancer to obtain useful proposals regarding minimum gross PM lengths to ensure a pathologically negative PM in TG or PG.

Patients and methods

Patient selection

In this retrospective study, data were retrieved from our prospectively developed database. We collected consecutive patients who underwent TG or PG for gastric cancer with gross EI or Siewert type II or III EGJ cancer at the Cancer Institute Hospital, Tokyo, Japan, between January 2005 and August 2021. We excluded patients who underwent endoscopic submucosal dissection, who had received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, or who had missing clinical data. Patients with a finally positive pathological PM, who did not undergo an additional resection, were excluded because we could not measure their PM length. Patients with EGJ cancer with gross EI > 40 mm were also excluded because the JGCTGs recommend the right transthoracic approach with upper mediastinal dissection for such disease [11, 15]. Patients with cT1 disease were classified into the superficial growth type (Sup), and those with cT2–4 disease were divided into two groups based on their preoperative examination findings of Exp or Inf. The classification basically fits the gross type of tumor defined by the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma (JCGC), 3rd English edition [16]; that is, type 1 and 2 tumors were classified as Exp, and type 3 and 4 tumors were classified as Inf. In patients with type 5 tumors, the findings of preoperative examinations were re-evaluated, and the tumors were then classified as Exp or Inf. Additionally, patients were divided into two groups on the basis of their postoperative histopathological findings: differentiated and undifferentiated types (Dif and Und). Dif contained well or moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma and papillary adenocarcinoma, while Und contained solid or non-solid types of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, signet-ring cell carcinoma, and mucinous adenocarcinoma according to the JCGC [16]. The clinical tumor status was also determined based on the JCGC [16] using endoscopy and enhanced computed tomography findings.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Cancer Institute Hospital (IRB No. 2020-0308).

Surgical procedures

All patients enrolled in the present study underwent TG or PG with D1 + lymphadenectomy for cT1N0 disease or D2 lymphadenectomy for cT1N (+) or cT2–4 disease involving lower esophagectomy via a transhiatal approach. The esophageal resection length was finally determined by attending surgeons according to tumor findings in intraoperative palpation and inspection of the serosal surface, considering the preoperative endoscopic and meal-study findings. Some patients preoperatively underwent another endoscopy to place marking clips on the pathologically intact mucosa proximal to the boundary of the tumor. In such patients, intraoperative endoscopic identification of the clips was mainly referred to when determining a transection line.

Measurement of gross and pathological PM lengths

As we previously reported [10, 14], fresh specimens were opened longitudinally, and the lymph nodes were removed for pathological examination; the specimen was then naturally spread out and pinned to a flat board with the mucosal side facing upward. The clinical tumor boundary was determined on the basis of the surgeons’ visual and tactile examinations of the tumor or the marking clips placed preoperatively. Furthermore, indigo carmine was sometimes applied to clarify the boundary. Gross findings were written in the individual chart and the specimen was finally photographed with a scale. The clinical tumor (cTumor) size, gross EI length, and gross PM length were referred to on the chart and additionally measured using these images to confirm them. Then, each specimen was fixed in a 10% buffered formalin solution for 48 h. Serial longitudinal sections of the tumor were made and subsequent pathological evaluation was performed according to the JCGC [16]. After pathological evaluation, the tumor was mapped using photographs of the fixed specimen. The location of the pathological proximal boundary and the pathological PM length were determined using this map** in the pathological report for daily practice.

Definition of parameters

In our previous study, we defined the length of a discrepancy between the gross and pathological proximal boundary of the tumor as the ΔPM, which shows how long the pathological tumor boundary extends beyond the gross boundary towards the proximal resection stump [10, 14]. In this study, the ΔPM was defined similarly. Details of the ΔPM are shown in Fig. 1. In a pathologically negative PM, the ΔPM could be calculated as follows: ΔPM = gross PM length − pathologically negative PM length.

Definition of parameters used in this study. We defined several parameters in this study to identify the minimum esophageal resection length. ΔPM indicates the length of discrepancies between clinical and pathological PM lengths in cases of a pathologically negative PM and b pathologically positive PM. PM proximal margin

When a PM was pathologically positive in the initial transection but negative in the additional transection, tumor lesions existed not only in the initially resected specimen but also in the additional resected specimen. Thus, the ΔPM could be calculated as follows: ΔPM = gross PM length in the initial specimen + pathologically positive PM length in the additional specimen.

In patients undergoing intraoperative frozen section (IFS) analysis, 3 mm, which was the width of specimens excised from the proximal stump for analysis, was added to this calculation.

Significance of ΔPM and analysis

We analyzed the ΔPM in the same way as in previous studies [10, 14]. We constructed histograms with the horizontal axis corresponding to the range of ΔPM length in 5-mm increments and the vertical axis corresponding to the number of patients. We defined the maximum ΔPM as the first value at which the number of patients became 0 in the plus direction on the respective histogram. According to this definition, no patient had cancer tissue of the length of the maximum ΔPM apart from the gross tumor boundary. Thus, we should transect the esophagus over the maximum ΔPM apart from the gross tumor boundary of the esophagus to obtain a pathologically negative PM.

Analysis of factors associated with long ΔPM

To identify risk factors of unexpected long ΔPM, we analyzed which factors were associated with ΔPM ≥ 10 mm using univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses. In the univariate analysis, type of disease (gastric cancer vs EGJ cancer), cTumor size (> 40 mm vs ≤ 40 mm), growth type (Inf vs Sup/Exp), gross EI length (> 13 mm vs ≤ 13 mm), and pathological type (Und vs Dif) were input as variates. Applying ROC analysis to the ΔPM status (ΔPM ≥ 10 mm or not), the optimal cutoff levels for the cTumor size and the gross EI length were 40 mm and 13 mm, respectively, with the area under the curve values of 0.706 and 0.551, respectively. In multivariate analysis, variates that were significantly associated with ΔPM ≥ 10 mm in the univariate analysis were input as covariates. Using selected factors that were independently associated with ΔPM ≥ 10 mm, subgroup analysis was performed to identify the maximum ΔPM in each subgroup.

Statistical analysis

Data on the patients’ clinicopathological parameters, including their tumor stage, were obtained by reviewing their medical charts, as we previously reported [10, 14]. Differences between variables were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test. All analyses were performed with JMP 13 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), and p values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

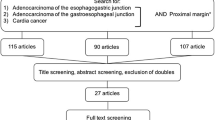

The data of 355 patients with gastric cancer with gross EI or EGJ cancer were collected; among these, the data of 289 patients were eligible and analyzed in this study (Supplementary Fig. 1). Table 1 lists the detailed clinicopathological characteristics of the eligible patients.

Histogram of ΔPM

A histogram of ΔPM in all patients is shown in Fig. 2. The maximum ΔPM was 25 mm.

Histograms of ΔPM in all patients. Histogram showing the distribution of ΔPM. The horizontal axes of the histograms correspond to the range of ΔPM in each increment and the longitudinal axes correspond to the number of patients. Dotted line indicates the first value at which the number of patients became 0 towards the plus direction, defined as the maximum ΔPM

Univariate and multivariate analyses of risk factors for ΔPM ≥ 10 mm.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses showed that cTumor size (> 40 mm), growth type (Inf), and pathological type (Und) were independently associated with ΔPM ≥ 10 mm (Table 2).

Histograms of ΔPM according to the risk factors

The maximum ΔPM was 15 and 25 mm when cTumor size was ≤ 40 and > 40 mm, respectively (Fig. 3a, b). The maximum ΔPM was 15, 20, and 25 mm when the growth type was Sup, Exp, and Inf, respectively (Fig. 3c–e). Furthermore, the maximum ΔPM was 25 and 20 mm when the pathological type was Dif and Und, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Histograms of ΔPM in subgroups. Histograms showing the distribution of ΔPM in the subgroups according to the factors that were associated with ΔPM ≥ 10 mm. a cTumor size ≤ 40 mm and b > 40 mm. c Sup growth type d Exp growth type, and e Inf growth type. cTumor clinical tumor, Sup superficial growth type, Exp expansive growth type, Inf infiltrative growth type

Possible incidences of pathologically positive PM

Tables 3 and 4 show the possible incidences of pathologically positive PM by respective gross PM length in each cTumor size and growth type. The minimum gross PM length is the shortest length at which the incidence of a pathologically positive PM is 0. The length has an equal meaning to the maximum ΔPM in the analysis of the histogram. Although the maximum ΔPM was 25 mm in cTumor size > 40 mm and Inf, the incidence of a pathologically positive PM was 0.53% and 0.68%, respectively, when the gross PM length was 20 mm in both diseases. The incidences according to the pathological type were not calculated because the calculation seemed improper.

Recommendation of minimum gross PM length

The minimum gross PM lengths to ensure a pathologically negative PM were suggested according to the analyses described above. Maintaining 25 mm is first recommended. When cTumor size is ≤ 40 mm or the growth type is Sup, 15 mm is alternatively recommended. When the growth type is Exp, 20 mm is an alternative. In other situations, considering the possible incidences of a pathologically positive PM, which are presented in Table 3 and 4, surgeons may transect the esophagus and submit the cutting edge to an IFS analysis to confirm it is pathologically negative.

Analysis of patients with pathologically positive PM

In this study, 13 patients were excluded from the main analysis because their PMs were pathologically positive for cancer, and an additional resection to obtain negative margins was not performed. All 13 patients had Inf disease, and 12 of the patients clinically had shorter PM lengths than our recommended PM lengths. However, in the remaining patient, the resected PM length was longer than our recommendation. The patient had an unexpected pathological extension of 24 mm beyond the gross proximal boundary of the tumor even though cTumor size was 35 mm. IFS analysis was not performed for this patient (Supplementary Table 1).

Survival outcomes according to ΔPM and pathological PM (pPM) length

Survival outcomes according to ΔPM and pPM length were evaluated. Applying ROC analysis to the survival status, the optimal cutoff levels for the ΔPM and the pPM length were 5 mm and 7 mm, respectively, with area under the curve values of 0.576 and 0.541, respectively. Supplementary Fig. 3 shows that the overall survival (OS) of the ΔPM ≥ 5 mm group was significantly worse than that of the ΔPM < 5 mm group (p < 0.0001). Furthermore, Supplementary Fig. 4 shows that the OS of the pPM ≥ 7 mm group was significantly better than that of the pPM < 7 mm group (p = 0.024).

To evaluate the relationship between the ΔPM and the pPM length, we constructed scatterplots of pPM length according to ΔPM. A significant negative correlation between ΔPM and pPM length was identified (p < 0.0001) (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Discussion

In this retrospective study, we focused on an unexpected pathological extension to the proximal side to identify the minimum gross PM length necessary to ensure a pathologically negative PM for gastric cancer with gross EI or EGJ cancer. There are three novel findings. First, the maximum ΔPM was 25 mm in all the patients. Second, cTumor size > 40 mm, Inf and Und were independently associated with ΔPM ≥ 10 mm. Third, in a subgroup analysis of ΔPM to possibly shorten the maximum ΔPM, the maximum ΔPM was 15 mm when cTumor size was ≤ 40 mm and the growth type was Sup. Furthermore, the maximum ΔPM was 20 mm when the growth type was Exp. On the basis of these new findings, we proposed new recommendations of gross PM length for gastric cancer with gross EI or EGJ cancer. They may make the safety margin to transect the esophagus more scientific and may also be useful in determining where surgeons should transect the esophagus, not only according to their tactile or visual examination but also based on scientific evidence.

A gross PM length of 25 mm as the first recommendation is relatively long. The esophageal resection length is critical in the procedure of transection and reconstruction in TG or PG for gastric cancer with gross EI or EGJ cancer. For such diseases, the length of EI plus a safety margin of 25 mm is a harvested esophageal length. A transhiatal resection of only 5 mm longer increases the difficulty of transection and anastomosis because of the anatomical features of the esophagus. Thus, providing all patients with such diseases with a gross PM length of 25 mm may increase the difficulty of surgery, although the incidence of each postoperative complication [17] was not different between the enrolled patients with long and short esophageal resection lengths (Supplementary Table 2).

Considering the discussion described above, we analyzed the relationship between the long ΔPM and several factors to identify patients who need a shorter PM length. In this analysis, we found that cTumor size > 40 mm, Inf and Und independently affected the length of ΔPM. Regarding the pathological type, the maximum ΔPM of Dif was longer than that of Und, even though Und included more patients with ΔPM ≥ 10 mm. Because of this discrepancy, we judged that the pathological type was not suitable for determining a shorter PM length that ensures a pathologically negative PM. We analyzed the possible incidences of pathologically positive PM only for cTumor size and growth type.

cTumor size and growth type information to modify the resection length are easily available. A PM length of 15 mm may be enough for cTumor size ≤ 40 mm and Sup disease. It may be natural that small or superficial disease has a shorter unexpected EI. This PM length is relatively shorter than other recommended lengths that were previously reported for gastric cancer [18]. However, the length is not so short considering that we have to resect the esophagus corresponding to the EI and PM. A length of 20 mm for Exp disease is also short compared with other recommendations. Although the difference of 5 mm between the recommendations for small tumors or Sup and Exp diseases is tiny, it may be adjustable in the magnified surgical view of laparoscopy. The shorter the esophageal resection length, the easier the dissection, transection, and reconstruction by the transhiatal approach. According to the difficulties of procedures, it may be possible to modify the esophageal resection length of cTumor size > 40 mm and Inf disease. On the basis of the results of this study, the incidences of pathologically positive PM with a gross PM length of 20 mm for cTumor size > 40 mm and Inf disease were less than 1%. When it is difficult to maintain a PM length of 25 mm for such disease, transecting the esophagus 20 mm apart from the proximal boundary of tumor and submitting it to IFS analysis is an acceptable way considering both technical and oncological safety. In other situations, some modifications using the current data regarding the incidences of pathologically positive PM in each type of disease may be reasonable according to the patient’s background.

Analyzing patients whose PMs were pathologically positive is quite useful. The esophagus was additionally resected because most of them had incurable factors in addition to a pathologically positive PM. Because 12 of 13 patients had shorter PM lengths than those we recommended, our new recommendations are reliable to a certain extent. However, we experienced a patient whose tumor was ≤ 40 mm in size but whose unexpected pathological EI was > 15 mm, which does not meet the results of the present study. This finding strongly indicates that the results of the present study are not definitive and that IFS analysis should be considered even if a resection length is maintained as per our recommendations.

The association between PM length and long-term survival outcomes remains controversial in gastric cancer. Several studies reported that the PM length did not influence survival outcomes in patients undergoing distal gastrectomy [19,20,21]. In contrast, Mine et al. [22] reported that a gross PM length ≤ 2 cm was an independent prognostic factor for patients with Siewert type II or III adenocarcinoma of EGJ cancer undergoing transhiatal esophagectomy. Although the results of the present study indicate only the minimum length required to obtain a secure PM length, the lengths obtained from previous and present studies are very similar. Therefore, not only to ensure a pathologically negative PM but also to obtain better survival outcomes, the lengths that we recommend based on the results of the present study should be maintained in daily practice. However, further studies are needed to truly determine whether the PM length influences the survival outcomes of patients with gastric cancer with gross EI or EGJ cancer.

Although we first recommend 25 mm for the gross PM length, several previous studies showed that a gross proximal margin length of 5–12 cm for EGJ cancer, which is much longer than our recommendations, is necessary because distant skip metastasis was often found [23,24,25,26]. However, these tumors with distant intramural skip metastasis often involve many lymph node or distant metastasis, leading to a poor prognosis even if removed completely [27, 28]. In this study, there were no patients with distant intramural skip metastasis detected by either preoperative examination or as a relapse in the residual esophagus.

This study has several limitations. First, it was a single-institution retrospective study. The total number of patients was relatively large, but the number of patients decreased when they were classified into subgroups. This may have reduced the reliability of our results for each subgroup. Second, we measured the gross PM length of the resected specimen stretched on the board. However, the intraoperative in-vivo gross PM length might be different to that measured on the back table. The length of the gross PM was affected by shrinkage of the esophagus after resection. A length of 20 mm in resected specimens corresponds to 23 mm before resection, based on the analysis performed by Siu et al. [29]. Finally, in the pathological examination, whole tumor sections were not always generated in daily practice. Thus, the longest pathological extension could exist at the site where a section was not made for pathological evaluation, potentially resulting in an overestimation of the pathological PM length. Considering these limitations, the results of this study should be carefully applied to daily practice.

Although the study had several indispensable weak points, we herein propose the first recommended PM lengths to ensure a pathologically negative PM for gastric cancer with gross EI or EGJ cancer. Surgeons can reasonably transect the esophagus using our recommendations instead of each surgeon’s individual decision according to visual and/or tactile sensation. However, our recommendations do not completely confirm the negativity of the PM. Combining our recommendations with IFS analysis is essential for daily practice.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–49.

Zhou Y, Zhang Z, Wu J, Ren D, Yan X, Wang Q, et al. A rising trend of gastric cardia cancer in Gansu Province of China. Cancer Lett. 2008;269:18–25.

Ahn HS, Lee HJ, Yoo MW, Jeong SH, Park DJ, Kim HH, et al. Changes in clinicopathological features and survival after gastrectomy for gastric cancer over a 20-year period. Br J Surg. 2011;98:255–60.

Ebihara Y, Okushiba S, Kawarada Y, Kitashiro S, Katoh H. Outcome of functional end-to-end esophagojejunostomy in totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2013;398:475–9.

Tsunoda S, Okabe H, Obama K, Tanaka E, Hisamori S, Kinjo Y, et al. Short-term outcomes of totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy: experience with the first consecutive 112 cases. World J Surg. 2014;38:2662–7.

Bozzetti F, Bonfanti G, Bufalino R, Menotti V, Persano S, Andreola S, Doci R, Gennari L. Adequacy of margins of resection in gastrectomy for cancer. Ann Surg. 1982;196:682–90.

Ha TK, Kwon SJ. Clinical importance of the resection margin distance in gastric cancer patients. J Korean Gastric Cancer Assoc. 2006;6:277–83.

Bissolati M, Desio M, Rosa F, Rausei S, Marrelli D, Chiari D, et al. Risk factor analysis for involvement of resection margins in gastric and esophagogastric junction cancer: an Italian multicenter study. Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:70–82.

Hallissey MT, Jewkes AJ, Dunn JA, Ward L, Fielding JW. Resection-line involvement after gastric cancer: a continuing problem. Br J Surg. 1993;80:1418–20.

Hayami M, Ohashi M, Kumagai K, Sano T, Hiki N, Nunobe S, et al. A “Just Enough” gross proximal margin length ensuring pathologically complete resection in distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Ann Surg Open. 2020;1(2):e026.

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2018 (ver. 5). Gastric Cancer. 2021;24:1–21.

Ajani JA, Bentrem DJ, Besh S, Gerdes H, Hayman JA, Scott WJ, et al. Gastric cancer, version 2.2013: featured updates to the NCCN Guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:531–46.

Smyth EC, Verheij M, Allum W, Cunningham D, Cervantes A, Arnold D, ESMO Guidelines Committee. Gastric cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:38–49.

Koterazawa Y, Ohashi M, Hayami S, Kumagai K, Sano T, Nunobe S, et al. Minimum esophageal resection length to ensure negative proximal margin in total gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Ann Surg Open. 2022;3(1):e127.

Kurokawa Y, Takeuchi H, Doki Y, Mine S, Terashima M, Yasuda T, et al. Map** of lymph node metastasis from esophagogastric junction tumors: a prospective nationwide multicenter study. Ann Surg. 2021;274:120–7.

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:101–12.

Clavien PA, Barkin J, de Oliveria ML, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complication: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009;250:187–96.

Berlth F, Kim WH, Choi JH, Park SH, Kong SH, Lee HJ, et al. Prognostic impact of frozen section investigation and extent of proximal safety margin in gastric cancer resection. Ann Surg. 2020;272:871–8.

Ohe H, Lee WY, Hong SW, Chang YG, Lee B. Prognostic value of the distance of proximal resection margin in patients who have undergone curative gastric cancer surgery. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;23(12):296.

Kim MG, Lee JH, Ha TK, Kwon SJ. The distance of proximal resection margin dose not significantly influence on the prognosis of gastric cancer patients after curative resection. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2014;87:223–31.

Hayami M, Ohashi M, Ishizuka N, Hiki N, Kumagai K, Souya N, et al. Oncological impact of gross proximal margin length in distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer: is the japanese recommendation valid? Ann Surg Open. 2021;2(1):e036.

Mine S, Sano T, Hiki N, Yamada K, Kosuga T, Nunobe S, et al. Proximal margin length with transhiatal gastrectomy for Siewert type II and III adenocarcinomas of the oesophagogastric junction. Br J Surg. 2013;100:1050–4.

Barbour AP, Rizk NP, Gonen M, Tang L, Bains MS, Coit DG, et al. Adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction: influence of esophageal resection margin and operative approach on outcome. Ann Surg. 2007;246:1–8.

Ito H, Clancy TE, Osteen RT, Swanson RS, Bueno R, Ashley AW, et al. Adenocarcinoma of the gastric cardia: what is the optimal surgical approach? J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:880–6.

Tsujitani S, Okuyama T, Orita H, Kakeji Y, Maehara Y, Sugimachi K, et al. Margins of resection of the esophagus for gastric cancer with esophageal invasion. Hepatogastroenterology. 1995;42:873–7.

Mariette C, Castel B, Balon JM, Seuningen IV, Triboulet JP, et al. Extent of oesophageal resection for adenocarcinoma of the oesophagogastric junction. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2003;29:588–93.

Takubo K. Pathology of the esophagus: an atlas and textbook. 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer; 2010.

von Rahden BH, Stein HJ, Feith M, Becker K, Siewert JR. Lymphatic vessel invasion as a prognostic factor in patients with primary resected adenocarcinomas of the esophagogastric junction. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:874–9.

Siu KF, Cheung HC, Wong J. Shrinkage of the esophagus after resection for carcinoma. Ann Surg. 1986;203:173–6.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YK and MO designed the protocol and drafted the manuscript, and all other authors participated in the design of the study. YK and MO analyzed the data. MH, RM, SI, KK, TS, and SN interpreted the data and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

10120_2023_1369_MOESM1_ESM.tif

Supplementary Figure 1. Patient flowchart of the enrollment process. From January 2005 to August 2021, 355 patients who had gastric cancer with esophageal invasion and esophagogastric junction cancer underwent total gastrectomy or proximal gastrectomy. After some patients were excluded, 289 patients were finally enrolled in this study. TG, total gastrectomy; PG, proximal gastrectomy; EI, esophageal invasion; EGJ, esophagogastric junction (TIF 103 KB)

10120_2023_1369_MOESM2_ESM.tif

Supplementary Figure 2. Histograms of ΔPM in subgroups. Histograms showing the distribution of ΔPM in the subgroups according to pathological type. (a) Dif and (b) Und disease. Dif, differentiated type; Und, undifferentiated type (TIF 80 KB)

10120_2023_1369_MOESM3_ESM.tif

Supplementary Figure 3. Kaplan–Meier estimates of OS according to ΔPM. The OS of the ΔPM ≥ 5 mm group (red line) was significantly worse than that of the ΔPM < 5 mm group (blue line) (p < 0.0001). The 5-year OS rates of the ΔPM ≥ 5 mm and < 5 mm groups were 36% and 60%, respectively. OS, overall survival (TIF 87 KB)

10120_2023_1369_MOESM4_ESM.tif

Supplementary Figure 4. Kaplan–Meier estimates of OS according to pPM length. The OS of the pPM ≥ 7 mm group (blue line) was significantly better than that of the pPM < 7 mm group (red line) (p = 0.024). The 5-year OS rates of the pPM ≥ 7 mm and < 7 mm groups were 57% and 43%, respectively. OS, overall survival. pPM, pathological PM (TIF 88 KB)

10120_2023_1369_MOESM5_ESM.tif

Supplementary Figure 5. Scatterplots of pPM length according to ΔPM. Scatterplots revealed a significant negative correlation between ΔPM and pPM length (p < 0.0001). pPM, pathological PM (TIF 108 KB)

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Koterazawa, Y., Ohashi, M., Hayami, M. et al. Required esophageal resection length beyond the tumor boundary to ensure a negative proximal margin for gastric cancer with gross esophageal invasion or esophagogastric junction cancer. Gastric Cancer 26, 451–459 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-023-01369-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-023-01369-2