Abstract

Background

In Western countries, gastric cancer (GC) is diagnosed when there is histological evidence of invasion into the lamina propria or beyond the submucosa. In Japan and some other countries, however, diagnosis of GC is based on the degree of structural and cytological abnormality of tumor glands. The aim of the present study was to compare the accuracy of the Western and Japanese criteria for diagnosis of GC.

Methods

The study included 233 consecutive patients with a postoperative diagnosis of submucosal invasive GC who underwent gastrectomy or endoscopic submucosal dissection. All pretreatment biopsy specimens were independently reviewed by two experts in gastrointestinal pathology employing both the Western and Japanese diagnostic criteria. Diagnostic agreement between pretreatment biopsy specimens and the corresponding resected specimens was evaluated, together with the interobserver agreement for each of the criteria.

Results

On the basis of the Western and Japanese criteria, the pretreatment biopsy diagnosis was noncancerous (including dysplasia) in 44 lesions and 1 lesion, respectively. Diagnostic accuracy based on biopsy was 81.1 % for the Western criteria and 99.5 % for the Japanese criteria (P < 0.001). Interobserver agreement based on the Western and Japanese criteria was 73.8 % and 96.5 %, respectively (P < 0.001). Invasion into the submucosa was detected by biopsy in only 25 cases.

Conclusions

The Japanese criteria are significantly more accurate for pretreatment biopsy diagnosis of GC. The Western criteria could lead to underdiagnosis of a lesion as high-grade dysplasia, even if submucosal invasive cancer is present.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The diagnostic criteria for “gastrointestinal cancer” differ between Western countries and Japan. In Western countries, gastric cancer (GC) is diagnosed when there is histological evidence of invasion into the lamina propria or beyond the submucosa [1–4], whereas in Japan and some other countries, diagnosis of GC is based on the degree of structural and cytological abnormality of the tumor glands [4–6]. In such a situation, lesions diagnosed as high-grade dysplasia (HGD) by Western pathologists have been diagnosed as GC by Japanese pathologists [2–4, 7, 8]. The differences in the two sets of diagnostic criteria are internationally well known. In the 1990s, gastrointestinal pathologists from all over the world proposed the Padova and Vienna gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasm classification as a means of interpreting the Western and Japanese diagnostic systems [9, 10]. However, the underlying difference between the two sets of diagnostic criteria has still not been resolved [11, 12], and they are still used independently in the West and East.

The choice of therapy is determined on the basis of pretreatment biopsy diagnosis. The lesion should be treated if it is diagnosed as cancer, but may be followed up if it is diagnosed as dysplasia. With improvements in endoscopy, small lesions can now be detected more easily than before [13, 14]. It has thus become increasingly important to diagnose pretreatment biopsy samples accurately. However, the Western diagnostic criteria, which are based on invasion, have a number of ambiguities, and similarly, the Japanese diagnostic criteria, which are based on structural and cytological abnormality, may have certain shortcomings. Accordingly, the main outcome of the present study was to compare the Western and Japanese diagnostic criteria in terms of accuracy for detection of GC. In addition, interobserver agreement of both diagnostic criteria was evaluated.

Materials and methods

Materials

We enrolled 233 consecutive patients with a postoperative diagnosis of submucosal invasive GC who underwent gastrectomy (142 cases) or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD, 91 cases) at Shizuoka Cancer Center Hospital (SCCH) between January 2010 and December 2011. All the patients underwent preoperative biopsy using endoscopic biopsy forceps (Radial Jaw 4, standard capacity; Boston Scientific, USA). The specimens obtained were fixed in 10 % formalin for 24 h at room temperature and then embedded in paraffin. Sections 3 μm thick were then cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

Specimens of submucosal invasive GC were used as controls, as definite submucosal invasion is the most acceptable definition of cancer for all pathologists. Submucosal invasive GC is diagnosed as “cancer” by both the Western and Japanese diagnostic criteria [15]. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) no pretreatment biopsy specimen obtained at SCCH; (2) previous chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy for GC.

All patients provided written informed consent for gastrectomy or ESD, and this study was approved by the institutional review board at our hospital (institutional code number: 24-J81-24-1-3).

Pathological review

Before pathological review, the defined histological findings of invasion (described below) were reconfirmed by four clinicians (M.Y., T.Sh, K.K., T.Su) through the use of training slide sets showing typical invasive lesions. All the pretreatment biopsy specimens were independently reviewed by two experts in gastrointestinal pathology (K.K., T.Su) who were blinded to the clinical information. These pathologists reviewed only H&E-stained slides and no immunohistochemically stained materials. In each case, biopsy specimens were diagnosed according to the Western and the Japanese diagnostic criteria. Biopsy specimens were also reviewed for the presence of the muscularis mucosa. After individual review, the two pathologists arrived at a final diagnosis through discussion.

Western diagnostic criteria

Histological evidence of invasion is required for diagnosis of GC [1, 4]. There are no universally accepted criteria for invasive growth into the lamina propria [16]. Therefore, histological findings of invasion are defined according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification and European management guidelines as follows: invasion into the muscularis mucosa or submucosa; lymphovascular invasion; infiltration of the stroma by single cells; small clusters of cells (small nest); small gland formation, and marked glandular crowding; excessive branching, budding, and a trabecular pattern; fused glands, cribriform glands; stromal response (desmoplasia) [6, 8]. For objective evaluation of invasion in this study, the Vienna Classification was used (Table 1) [9]. Category 5.1 or 5.2 was diagnosed as cancer because of evident invasion. Category 4.3 was also diagnosed as cancer because the lesion was suspected to be invasive. Categories 1, 2, 3, and 4.1 were diagnosed as noncancerous lesions because of lack of any evidence of invasion. Category 4.2 was not used in this study because it was created to understand the Japanese diagnosis of noninvasive carcinoma (carcinoma in situ) from a Western point of view.

Japanese diagnostic criteria

Structural and cytological abnormalities are necessary for diagnosis of GC regardless of the presence of invasion [5, 6]. Features of cytological abnormality included variation in nuclear size and shape; presence of hyperchromatic, large, spherical, vesicular nuclei; irregularly clumped chromatin; increased frequency of mitotic figures; pseudostratified nuclei; poor cellular differentiation; increased nuclear-to-cytoplasm (N/C) ratio; and loss of nuclear polarity. Features of structural abnormality included increased crypt complexity with crowding, branching glandular epithelium, fused glands, budding, a cribriform pattern, and variability of crypt size and shape [17, 18]. As an objective method of defining different levels of abnormality, the Group Classification of the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association was used (Table 2) [19]. Group 5 was diagnosed as cancer. Group 4 was defined as neoplasia or suspected cancer. Groups 1, 2, and 3 were diagnosed as noncancerous lesions.

Statistical analysis

The final pathological diagnosis based on resected specimens, which was submucosal invasive GC in all cases, was defined as the standard. Diagnostic agreement between pretreatment biopsy specimens and the corresponding resected specimens, and the interobserver agreement for each of the criteria, were evaluated.

Counts and percentages were calculated for all categorical variables. Interobserver agreement was calculated as the number of concordant lesions/total number of lesions. Accuracy was calculated as the number of cases diagnosed as carcinoma/total number of lesions. Statistical significance was defined as a P < 0.05 with two-tailed tests. Comparison of accuracy and interobserver agreement between the Western and Japanese criteria was performed using χ 2 test. The data were analyzed using the SPSS statistical analysis software package (IBM SPSS Statistics, version 21).

Results

Interobserver agreement

The diagnoses submitted by the two pathologists are detailed in Tables 3 and 4. Use of the Vienna Classification yielded 172 concordant cases and the Group Classification 225 concordant cases, the interobserver agreement being 73.8 % and 96.5 %, respectively (Table 5). There was a statistically significant difference in interobserver agreement between the Vienna Classification and the Group Classification (P < 0.001). There were 29 cases of disagreement between Categories 4.1 and 5.1 in the Vienna Classification, compared with 6 such cases between Groups 4 and 5 in the Group Classification.

Accuracy of diagnosis of gastric cancer

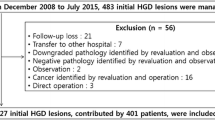

The submitted final diagnoses are detailed in Tables 6 and 7. The pretreatment biopsy diagnosis was noncancerous in 44 lesions based on the Western criteria, and in only 1 lesion based on the Japanese criteria, and the diagnostic accuracy based on biopsy was 81.1 % and 99.5 %, respectively, the difference being significant (P < 0.001). In disagreement cases between diagnosis based on the Western criteria and Japanese criteria, 43 lesions were diagnosed as Category 4.1 in the Vienna Classification and Group 5 in the Group Classification (Fig. 1). Among the biopsy specimens, 187 (80.2 %) contained the muscularis mucosa, and invasion into the submucosa was detected in 25 (10.7 %).

Disagreement case between the Western and Japanese diagnoses. a, b Pretreatment biopsy specimen. This lesion was diagnosed as high-grade dysplasia (Category 4.1) based on the Western criteria, and definite cancer (Group 5) based on the Japanese criteria. c, d The corresponding resected specimen. The lesion was submucosal invasive gastric cancer

Discussion

A tumor is considered a “cancer” only if its cells have acquired the ability to invade into surrounding tissue [20]. Therefore, pathologists always attempt to identify morphological features that suggest such invasiveness. The aim of the present study was to clarify those diagnostic criteria that would be more accurate indicators of invasive ability.

The Japanese diagnostic criteria had a significantly higher accuracy rate. Overall, histological discrepancy between diagnosis based on biopsy and that based on the corresponding resected specimens was seen in 44 cases (18.8 %) when the Western criteria were used, and in only 1 case (0.4 %) when the Japanese criteria were employed. Other recent studies have reported that the discrepancy rate based on the Western criteria is 2.7–44.5 % [21].

One hundred eighty-seven cases (80.2 %) contained the muscularis mucosa in preoperative biopsy specimens, and submucosal invasion was detected in only 25 cases (10.7 %). Most of the biopsy specimens were thus mucosal. Based on the Japanese criteria, pathologists were able to detect GC irrespective of biopsy status. Forty-three cases (18.4 %) were diagnosed as HGD. Thus, in the West, many patients with submucosal GC might be diagnosed as HGD on the basis of biopsy.

Use of the Japanese criteria also produced better interobserver agreement. It might not be fair to compare the Vienna Classification and the Group Classification because the Vienna Classification had more categories than the Group Classification. However, the disagreement cases of Japanese criteria were seen in only eight cases. Six of these disagreement cases were Group 4 (suspected carcinoma) versus Group 5 (definite carcinoma). Diagnosis of Group 4 was the result of the small and fragmented state of the biopsy specimens in all cases.

The prevalence of GC has been historically high in Japan. In the 1960s, the age-adjusted mortality rate from GC (annual number of newly recorded deaths adjusted by the standard world population, per 100,000 people) was approximately 65 for males and 35 for females, and GC was the most frequent cause of cancer death [22]. On the basis of the differences seen between biopsy and resection specimens, Japanese gastrointestinal pathologists established the Japanese diagnostic criteria [23, 24]. Japanese pathologists consider that structural and cytological abnormalities are indicative of invasive ability. With regard to this point, there is an essential difference between the West and Japan.

Advances in medical equipment and implementation of the Japanese pathological diagnostic system have led to early detection of GC and relatively good therapeutic results [15, 25–27]. In Japan, the number of new GC patients in 2006 was estimated to be 116,911 [28]; more than half of the newly diagnosed lesions were early GC, i.e., carcinoma limited to the mucosa or submucosa [29, 30], for which endoscopic curative treatment is indicated [31–33]. Early detection and accurate diagnosis have a strong impact on cancer care. In fact, the mortality rate from GC in Japan has been decreasing dramatically [10, 11, 28]; in 2006, the age-adjusted mortality rate was 21.7 for males and 8.4 for females [22].

Our results suggest that use of the Western criteria made it difficult to detect evidence of invasion in biopsy specimens, and in fact diagnostic discrepancy was evident between biopsy and resected specimens in many cases. A number of previous studies have suggested that low-grade dysplasia (LGD) progresses to HGD [34–37], and that HGD becomes invasive GC within several months [38–43]. In 20–40 % of cases, diagnostic discrepancy between dysplasia evident at biopsy and GC observed in the resection specimen has been reported [34, 37, 44]. In most cases, the lesions were thought to be cancer at the time of initial biopsy [1, 44–47].

From a Western point of view, the final diagnosis rests on examination of the surgical or ESD specimen, because there is some possibility of cancer even if the diagnosis is LGD or HGD [21, 23, 36, 46–48]. Some studies have indicated that LGD and HGD should be treated, because genomic instability may already be present [49–52]. However, the European guidelines recommend reassessment with biopsy sampling and surveillance at 6-month to 1-year intervals for patients with HGD in the absence of endoscopically defined lesions [8]. According to whether there is evidence of invasion, there is a potential risk of underdiagnosing a lesion as LGD or HGD, even if it is submucosal or advanced GC. Moreover, there is a higher possibility of LGD if only the WHO classification is used for diagnosis because the features of invasion are more strictly limited in this classification. Pretreatment biopsy drives therapeutic decision making, and if diagnoses are inconsequent, clinicians run the risk of misleading patients with regard to prognosis and treatment.

The limitation was that findings of invasion were limited. However, as there is no complete consensus about these features among pathologists worldwide, we did not expect complete consensus because interobserver agreement was insufficient [53]. Basically, it is crucial to bear in mind that some cases are impossible to diagnose as GC if evidence of invasion is the only criterion.

In conclusion, the Japanese diagnostic criteria are considered to be significantly more accurate for detection of GC than the Western criteria. Early detection and accurate diagnosis offer patients a much higher chance of cure. These diagnostic criteria should contribute to reducing mortality caused by GC in the era of minimally invasive treatment.

References

Lansdown M, Quirke P, Dixon MF, Axon AT, Johnston D. High grade dysplasia of the gastric mucosa: a marker for gastric carcinoma. Gut. 1990;31(9):977–83.

Schlemper RJ, Itabashi M, Kato Y, Lewin KJ, Riddell RH, Shimoda T, et al. Differences in the diagnostic criteria used by Japanese and Western pathologists to diagnose colorectal carcinoma. Cancer (Phila). 1998;82(1):60–9.

Schlemper RJ, Dawsey SM, Itabashi M, Iwashita A, Kato Y, Koike M, et al. Differences in diagnostic criteria for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma between Japanese and Western pathologists. Cancer (Phila). 2000;88(5):996–1006.

Schlemper RJ, Itabashi M, Kato Y, Lewin KJ, Riddell RH, Shimoda T, et al. Differences in diagnostic criteria for gastric carcinoma between Japanese and Western pathologists. Lancet. 1997;349(9067):1725–9.

Rubio CA, Kato Y. DNA profiles in mitotic cells from gastric adenomas. Am J Pathol. 1988;130(3):485–8.

Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND. WHO classification of tumors of the digestive system. 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); 2010. p. 10-4.

Kim JM, Cho MY, Sohn JH, Kang DY, Park CK, Kim WH, et al. Diagnosis of gastric epithelial neoplasia: dilemma for Korean pathologists. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(21):2602–10.

Dinis Ribeiro M, Areia M, de Vries AC, Marcos Pinto R, Monteiro Soares M, O’Connor A, et al. Management of precancerous conditions and lesions in the stomach (MAPS): guideline from the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), European Helicobacter Study Group (EHSG), European Society of Pathology (ESP), and the Sociedade Portuguesa de Endoscopia Digestiva (SPED). Endoscopy. 2012;44(1):74–94.

Schlemper RJ, Riddell RH, Kato Y, Borchard F, Cooper HS, Dawsey SM, et al. The Vienna classification of gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia. Gut. 2000;47(2):251–5.

Rugge M, Correa P, Dixon MF, Hattori T, Leandro G, Lewin K, et al. Gastric dysplasia: the Padova international classification. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24(2):167–76.

Kushima R, Kim KM. Interobserver variation in the diagnosis of gastric epithelial dysplasia and carcinoma between two pathologists in Japan and Korea. J Gastric Cancer. 2011;11(3):141–5.

Downs-Kelly E, Mendelin JE, Bennett AE, Castilla E, Henricks WH, Schoenfield L, et al. Poor interobserver agreement in the distinction of high-grade dysplasia and adenocarcinoma in pretreatment Barrett’s esophagus biopsies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(9):2333–40 (quiz 41).

Kato M, Kaise M, Yonezawa J, Toyoizumi H, Yoshimura N, Yoshida Y, et al. Magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging achieves superior accuracy in the differential diagnosis of superficial gastric lesions identified with white-light endoscopy: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72(3):523–9.

Ezoe Y, Muto M, Uedo N, Doyama H, Yao K, Oda I, et al. Magnifying narrowband imaging is more accurate than conventional white-light imaging in diagnosis of gastric mucosal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(6):2017.e3–2025.e3.

Stolte M. Diagnosis of gastric carcinoma: Japanese fairy tales or Western deficiency? Virchows Arch. 1999;434(4):279–80.

Rubio CA, Nesi G, Messerini L, Zampi GC, Mandai K, Itabashi M, et al. The Vienna classification applied to colorectal adenomas. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21(11):1697–703.

Lewin KJ, Appelman HD. Tumors of the esophagus and stomach. Washington, DC: American Registry of Pathology; 1996. p. 245–330.

Ming S-C, Goldman H. Pathology of the gastrointestinal tract. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1998. p. 607–47.

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14(2):101–12.

Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P. Molecular biology of the cell. 5th ed. New York: Garland Science; 2008. p. 1205–68.

Lee CK, Chung IK, Lee SH, Kim SP, Lee SH, Lee TH, et al. Is endoscopic forceps biopsy enough for a definitive diagnosis of gastric epithelial neoplasia? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25(9):1507–13.

Vital Statistics Japan. Cancer mortality 1958-2012 (internet). http://ganjoho.jp/professional/statistics/statistics.html. Accessed Dec 2013.

Schlemper RJ, Kato Y, Stolte M. Review of histological classifications of gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia: differences in diagnosis of early carcinomas between Japanese and Western pathologists. J Gastroenterol. 2001;36(7):445–56.

Takahashi T, Iwama N. Three-dimensional microstructure of gastrointestinal tumors. Gland pattern and its diagnostic significance. Pathol Annu. 1985;20(Pt 1):419–40.

Stolte M. The new Vienna classification of epithelial neoplasia of the gastrointestinal tract: advantages and disadvantages. Virchows Arch. 2003;442(2):99–106.

Hisamichi S, Sugawara N. Mass screening for gastric cancer by X-ray examination. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1984;14(2):211–23.

Ferlay J, Shin H-R, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin D. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(12):2893–917.

Matsuda T, Marugame T, Kamo K-I, Katanoda K, Ajiki W, Sobue T. Cancer incidence and incidence rates in Japan in 2006: based on data from 15 population-based cancer registries in the monitoring of cancer incidence in Japan (MCIJ) project. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2012;42(2):139–47.

Nashimoto A, Akazawa K, Isobe Y, Miyashiro I, Katai H, Kodera Y, et al. Gastric cancer treated in 2002 in Japan: 2009 annual report of the JGCA nationwide registry. Gastric Cancer. 2012. doi:10.1007/s10120-012-0163-4.

Kitano S, Shiraishi N. Current status of laparoscopic gastrectomy for cancer in Japan. Surg Endosc. 2004;18(2):182–5.

Ono H, Kondo H, Gotoda T, Shirao K, Yamaguchi H, Saito D, et al. Endoscopic mucosal resection for treatment of early gastric cancer. Gut. 2001;48(2):225–9.

Ono H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer. Chin J Dig Dis. 2005;6(3):119–21.

Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010, ver. 3. Gastric Cancer 2011;14(2):113–123.

Jung SH, Chung WC, Lee KM, Paik CN, Jung JH, Lee MK, et al. Risk factors in malignant transformation of gastric epithelial neoplasia categorized by the revised Vienna classification: endoscopic, pathological, and immunophenotypic features. Gastric Cancer. 2010;13(2):123–30.

Takenawa H, Kurosaki M, Enomoto N, Miyasaka Y, Kanazawa N, Sakamoto N, et al. Differential gene-expression profiles associated with gastric adenoma. Br J Cancer. 2004;90(1):216–23.

Park SY, Jeon SW, Jung MK, Cho CM, Tak WY, Kweon YO, et al. Long-term follow-up study of gastric intraepithelial neoplasias: progression from low-grade dysplasia to invasive carcinoma. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20(10):966–70.

Schlemper RJ, Kato Y, Stolte M. Well-differentiated adenocarcinoma or dysplasia of the gastric epithelium: rationale for a new classification system. Verh Dtsch Ges Pathol. 1999;83:62–70.

Kokkola A, Haapiainen R, Laxen F, Puolakkainen P, Kivilaakso E, Virtamo J, et al. Risk of gastric carcinoma in patients with mucosal dysplasia associated with atrophic gastritis: a follow up study. J Clin Pathol. 1996;49(12):979–84.

Rugge M, Farinati F, Di Mario F, Baffa R, Valiante F, Cardin F. Gastric epithelial dysplasia: a prospective multicenter follow-up study from the interdisciplinary group on gastric epithelial dysplasia. Hum Pathol. 1991;22(10):1002–8.

Rugge M, Farinati F, Baffa R, Sonego F, Di Mario F, Leandro G, et al. Gastric epithelial dysplasia in the natural history of gastric cancer: a multicenter prospective follow-up study. Interdisciplinary group on gastric epithelial dysplasia. Gastroenterology. 1994;107(5):1288–96.

Di Gregorio C, Morandi P, Fante R, De Gaetani C. Gastric dysplasia. A follow-up study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88(10):1714–9.

Saraga EP, Gardiol D, Costa J. Gastric dysplasia. A histological follow-up study. Am J Surg Pathol. 1987;11(10):788–96.

Fertitta AM, Comin U, Terruzzi V, Minoli G, Zambelli A, Cannatelli G, et al. Clinical significance of gastric dysplasia: a multicenter follow-up study. Gastrointestinal endoscopic pathology study group. Endoscopy. 1993;25(4):265–8.

Schlemper RJ, Kato Y, Stolte M. Diagnostic criteria for gastrointestinal carcinomas in Japan and Western countries: proposal for a new classification system of gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15(suppl):G49–57.

Yamada H, Ikegami M, Shimoda T, Takagi N, Maruyama M. Long-term follow-up study of gastric adenoma/dysplasia. Endoscopy. 2004;36(5):390–6.

Hull MJ, Mino-Kenudson M, Nishioka NS, Ban S, Sepehr A, Puricelli W, et al. Endoscopic mucosal resection: an improved diagnostic procedure for early gastroesophageal epithelial neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30(1):114–8.

Kim YJ, Park JC, Kim JH, Shin SK, Lee SK, Lee YC, et al. Histologic diagnosis based on forceps biopsy is not adequate for determining endoscopic treatment of gastric adenomatous lesions. Endoscopy. 2010;42(8):620–6.

Dixon MF. Gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia: Vienna revisited. Gut. 2002;51(1):130–1.

Otaki T, Kohli Y, Fujiki N, Imamura Y, Fukuda M. Early progression stage of malignancy as revealed by immunohistochemical demonstration of DNA instability: I. Human gastric adenomas. Eur J Histochem. 1994;38(4):281–90.

Sun A, Noriki S, Imamura Y, Fukuda M. Detection of cancer clones in human gastric adenoma by increased DNA-instability and other biomarkers. Eur J Histochem. 2003;47(2):111–22.

Fukuda M, Sun A. The DNA-instability test as a specific marker of malignancy and its application to detect cancer clones in borderline malignancy. Eur J Histochem. 2005;49(1):11–26.

Chung WC, Jung SH, Lee KM, Paik CN, Kwak JW, Jung JH, et al. Genetic instability in gastric epithelial neoplasias categorized by the revised Vienna classification. Gut Liver. 2010;4(2):179–85.

Patil D, Goldblum J, Rybicki L, Plesec T, Mendelin J, Bennett A, et al. Prediction of adenocarcinoma in esophagectomy specimens based upon analysis of preresection biopsies of Barrett esophagus with at least high-grade dysplasia: a comparison of 2 systems. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36(1):134–41.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank our institutional secretaries for assisting with the collection of the specimens. This work was supported by Shizuoka Cancer Center. M.Y. and T.Sh. designed the research study. M.Y. retrieved clinical and pathological data. Biopsy specimens were reviewed and diagnosed by K.K. and T.Su. Statistical analysis was performed by M.Y. The manuscript was written by M.Y., K.K., T.Su., T.N., H.O. and T.Sh. and approved by all contributing authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yoshida, M., Shimoda, T., Kusafuka, K. et al. Comparative study of Western and Japanese criteria for biopsy-based diagnosis of gastric epithelial neoplasia. Gastric Cancer 18, 239–245 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-014-0382-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-014-0382-y