Abstract

Purpose

To investigate a possible link between acute Epstein-Barr virus infection and Lemierre syndrome, a rare yet life-threatening infection.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted adhering to the 2020 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. Diagnosis criteria for Lemierre syndrome were established, and data extraction encompassed demographic data, clinical, and laboratory information.

Results

Out of 985 initially identified papers, 132 articles were selected for the final analysis. They reported on 151 cases of Lemierre syndrome (76 female and 75 male patients with a median of 18 years) alongside interpretable results for Epstein-Barr virus serology. Among these, 38 cases (25%) tested positive for acute Epstein-Barr virus serology. There were no differences in terms of age, sex, or Fusobacterium presence between the serologically positive and negative groups. Conversely, instances of cervical thrombophlebitis and pulmonary complications were significantly higher (P = 0.0001) among those testing negative. The disease course was lethal in one case for each of the two groups.

Conclusions

This analysis provides evidence of an association between acute Epstein-Barr virus infection and Lemierre syndrome. Raising awareness of this link within the medical community is desirable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Lemierre syndrome, also known as postanginal sepsis or necrobacillosis, is an infrequent yet potentially fatal infection, that usually affects immunocompetent individuals. It is characterized by an acute oropharyngeal inflammation, which is followed by a septic cervical (mostly jugular) thrombophlebitis, which, in turn, leads to the dissemination of septic emboli [1,2,3,4]. Fusobacterium species, part of the oral microbiota, are the primary causative agents [1,2,3,4]. The condition was initially documented in 1900 by Paul Courmont [5], followed by Mark S. Reuben in 1936 [6]. However, André Lemierre in France provided the most detailed description in 1936 [7].

Viral agents may compromise mucous membrane integrity, providing an entry point for bacterial pathogens and increasing the susceptibility to various invasive infections, including those caused by meningococci [8, 9]. A link between acute infection caused by the human herpes virus 4, also known as Epstein-Barr virus [10, 11], and Lemierre syndrome has been suggested [3]. This report aims to systematically explore this association.

Methods

This systematic review (registered on INPALSY, number 202410102) adhered to the 2020 edition of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [12]. The data were sourced from Web of Science, the United States National Library of Medicine, and Excerpta Medica. The search strategy focused on the term "Lemierre syndrome" across the three databases. Additionally, articles identified in the references of retrieved records, reports available in Google Scholar, and articles already familiar to the authors were included [13]. The searches were conducted in July 2023 and repeated prior to submission (February 28, 2024).

Eligible were reports of apparently immunocompetent patients with a diagnosis of Lemierre syndrome and with either a positive or negative serology for Epstein-Barr virus.

Since a formal case definition for Lemierre syndrome has not yet been established [1,2,3,4], we established this diagnosis in patients with an acute onset pharyngeal inflammation associated with (a) isolation of Fusobacterium species from a blood culture or a normally sterile site, or (b) a cervical thrombophlebitis associated with one of the following features: pulmonary involvement (infiltrates, septic emboli, abscesses, or empyema; an isolated pleural effusion was not considered sufficient to define lung impairment); metastatic extra-pulmonary involvement such as abscesses or septic emboli; or isolation of a germ other than Fusobacterium from a blood culture or a normally sterile site. Cases of Lemierre syndrome temporally associated with a urogenital infection, or surgery were excluded. Cases related to a significant odontogenic infection were also not included [14]. A local spread of the oropharyngeal infection was not regarded as systemic involvement in the diagnosis of Lemierre syndrome.

Patients with a positive Paul-Bunnell-Davidsohn heterophile test, IgM and IgG antibodies to the Epstein-Barr viral capsid, or IgG antibodies to the early Epstein-Barr viral antigen were deemed to have a positive serology for acute Epstein-Barr Virus infection [10, 11]. Conversely, the serology for acute Epstein-Barr Virus infection was considered negative in cases with isolated IgG antibodies to the Epstein-Barr viral capsid; negativity for IgM antibodies to the Epstein-Barr viral capsid; positivity for IgG to Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen; or negative Paul-Bunnell-Davidsohn test [10, 11]. Cases that were reported as serologically positive respectively negative for an acute Epstein-Barr virus infection but lacked information regarding the performed serological tests were also included. For both Epstein-Barr virus positive and negative cases, demographic details, clinical and laboratory data, and outcomes were collected.

Two authors in duplicate conducted the literature search, selected eligible studies, extracted data, and assessed the comprehensiveness of each included case. Disagreements were resolved through discussions, involving a senior author if needed. One author inputted data into a worksheet, and the second author verified data accuracy.

The omnibus normality test disclosed that continuous variables were not normally distributed [15]. Hence, the latter are presented as median and interquartile range, and their analysis was conducted using the Mann–Whitney-Wilcoxon test for two independent samples [16]. Categorical variables are expressed as counts and were analyzed by means of the Fisher exact test [16]. A significance level was assigned at < 0.05 for a two-sided P-value.

Results

The literature search process is outlined in Fig. 1. The full-text of 1001 papers was assessed. For the final analysis, we included 132 articles [see: supplementary document] published after 1979: 70 from America (United States of America, N = 64; Canada, N = 5; Jamaica, N = 1), 53 from Europe (United Kingdom, N = 15; Germany, N = 6; France, N = 5; Greece, N = 5; Spain, N = 4; Denmark, N = 3; Netherlands, N = 3; Belgium, N = 2; Italy, N = 2; Portugal, N = 2; Sweden, N = 2; Switzerland, N = 2; Austria, N = 1; Norway, N = 1) and 9 from Asia (Türkiye, N = 3; Israel, N = 2; Japan, N = 2; Pakistan, N = 1; Sri Lanka, N = 1). One hundred twenty-two articles were written in English, three in French, three in German, two in Spanish, and each one in Norwegian and Swedish. The mentioned 132 articles [15–146] described subjects with a Lemierre syndrome and an interpretable serology for Epstein-Barr virus.

The mentioned reports provided information about 151 cases of Lemierre syndrome (76 female and 75 male individuals 18 [16–23] years of age) with an interpretable serology for Epstein-Barr virus infection (Table 1). The acute Epstein-Barr virus serology was positive in 38 (25%) and negative in 113 (75%) cases. Cases with and without serological evidence of acute Epstein-Barr virus infection did not significantly differ with respect to female-male-ratio, age, positivity for Fusobacterium species or extrapulmonary involvement. A cervical thrombophlebitis (75% versus 39%) and a pulmonary involvement (87% versus 55%) were more frequently (P = 0.0001) observed in cases with a negative acute Epstein-Barr virus serology. The disease course was lethal in one case for each of the two groups.

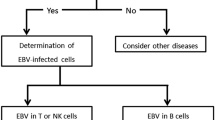

The serology for acute Epstein-Barr virus infection was never positive in individuals ≤ 10 and ≥ 41 years of age (Fig. 2).

Discussion

Lemierre syndrome [1,2,3,4] and Epstein-Barr virus [10, 11] infectious mononucleosis predominantly occur in otherwise healthy teenagers and young adults. A link between Lemierre syndrome and serological evidence of acute Epstein-Barr virus infection was first proposed in the eighties of last century [3]. In this analysis of the literature, we identified a positive serology for an acute Epstein-Barr virus infection in 38 (25%) out of 151 patients diagnosed with Lemierre syndrome. Hence, these data allow to infer that Epstein-Barr virus infection may sporadically predispose individuals to develop Lemierre syndrome.

At least two mechanisms might underly the link between Epstein-Barr virus infection and Lemierre syndrome. Firstly, there is a higher prevalence of Fusobacterium positivity in individuals with infectious mononucleosis as opposed to those who are healthy [17]. Furthermore, in instances where the Fusobacterium swab yields positive results, the bacterial load is elevated in patients with infectious mononucleosis [17]. Secondly, the infiltration of bacteria into the tonsillar epithelium is increased in individuals with Epstein-Barr virus infectious mononucleosis [18].

Cervical thrombophlebitis and pulmonary involvement occurred more frequently in instances where there was a negative acute Epstein-Barr virus serology. The reasons behind this observation remain unexplained.

This analysis exhibits both limitations and strengths. The main weakness is the limited dataset: only 151 instances of Lemierre syndrome with associated Epstein-Barr virus serology were detected, highlighting the need for broader, prospective research. However, the rarity of this condition, evidenced by a Danish report of an incidence rate of 3.6 per million annually [19], complicates such research efforts. In contrast, the study’s strengths include adherence to established methodologies and the comprehensive analysis of data from three distinct databases.

Conclusion

This literature review, taken together with experimental data [127, 18], support the link between Epstein-Barr virus infectious mononucleosis and Lemierre syndrome, highlighting the importance of increasing awareness within the medical community. Even though it is rare, healthcare providers should keep Lemierre syndrome in mind when infectious mononucleosis patients acutely present with high fever, deterioration of general well-being, unilateral neck pain, or shortness of breath.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were generated in this study.

References

Sinave CP, Hardy GJ, Fardy PW (1989) The Lemierre syndrome: suppurative thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein secondary to oropharyngeal infection. Medicine (Baltimore) 68(2):85–94

Chirinos JA, Lichtstein DM, Garcia J, Tamariz LJ (2002) The evolution of Lemierre syndrome: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 81(6):458–465. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005792-200211000-00006

Riordan T (2007) Human infection with Fusobacterium necrophorum (Necrobacillosis), with a focus on Lemierre’s syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev 20(4):622–659. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00011-07

Wright WF, Shiner CN, Ribes JA (2012) Lemierre syndrome. South Med J 105(5):283–288. https://doi.org/10.1097/SMJ.0b013e31825581ef

Courmont P, Cade A (1900) Sur une septico-pyohémie de l’homme simulant la peste et causée par un strepto-bacille anaérobie. Arch Med Exp Anat Pathol 12(4):393–418

Reuben MS (1931) Post-anginal sepsis: sepsis of oro-naso-pharyngeal origin. Arch Dis Child 6(32):115–128. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.6.32.115

Lemierre A (1936) On certain septicaemias du to anaerobic organisms. Lancet 227(5874):701–703. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)57035-4

Cartwright KA, Jones DM, Smith AJ, Stuart JM, Kaczmarski EB, Palmer SR (1991) Influenza A and meningococcal disease. Lancet 338(8766):554–557. https://doi.org/10.1016/0140-6736(91)91112-8

Salomon A, Berry I, Tuite AR, Drews S, Hatchette T, Jamieson F, Johnson C, Kwong J, Lina B, Lojo J, Mosnier A, Ng V, Vanhems P, Fisman DN (2020) Influenza increases invasive meningococcal disease risk in temperate countries. Clin Microbiol Infect 26(9):1257.e1-1257.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2020.01.004

Jenson HB (2011) Epstein-Barr virus. Pediatr Rev 32(9):375–384. https://doi.org/10.1542/pir.32-9-375

Balfour HH Jr, Dunmire SK, Hogquist KA (2015) Infectious mononucleosis. Clin Transl Immunol 4(2):33. https://doi.org/10.1038/cti.2015

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol 134:178–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.03.001

Haddaway NR, Collins AM, Coughlin D, Kirk S (2015) The role of Google Scholar in evidence reviews and its applicability to grey literature searching. PLoS ONE 10(9):e0138237. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138237

Ogle OE (2017) Odontogenic infections. Dent Clin North Am 61(2):235–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cden.2016.11.004

Poitras G (2006) More on the correct use of omnibus tests for normality. Econ Lett 90(3):304–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2005.08.016

Brown GW, Hayden GF (1985) Nonparametric methods. Clinical applications. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 24(9):490–498. https://doi.org/10.1177/000992288502400905

Jensen A, Hagelskjaer Kristensen L, Prag J (2007) Detection of Fusobacterium necrophorum subsp. funduliforme in tonsillitis in young adults by real-time PCR. Clin Microbiol Infect. 13(7):695–701. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007

Stenfors LE, Bye HM, Räisänen S, Myklebust R (2000) Bacterial penetration into tonsillar surface epithelium during infectious mononucleosis. J Laryngol Otol 114(11):848–852. https://doi.org/10.1258/0022215001904149

Hagelskjaer LH, Prag J, Malczynski J, Kristensen JH (1998) Incidence and clinical epidemiology of necrobacillosis, including Lemierre’s syndrome, in Denmark 1990–1995. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 17(8):561–565. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01708619

Acknowledgements

We gratefully dedicate this work to the memory of Professor Jürg Pfenninger (15 October 1943 – 25 August 2014), who made us aware of the possible connection between Epstein-Barr mononucleosis and Lemierre syndrome.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Milano within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. The study was partially funded by the Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Corrente).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: AAD, SMMAM, RG, SAGL, GPM, MGB, GB; Formal analysis: AAD, SMMAM; Project administration: SAGL, GPM, MGB; Supervision: PBF, LK; Original draft of the manuscript: AAD, SMMAM, MGB, PBF, LK; Review and editing of the manuscript: all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no competing interests relevant to the content of this article. The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Ethical approval.

The study was performed in accordance with ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Helsinki Declaration.

Consent for participation

Not applicable (literature review).

Consent for publication

Not applicable (literature review).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Delcò, A.A., Montorfani, S.M.M.A., Gualtieri, R. et al. Epstein-Barr virus as promoter of Lemierre syndrome: systematic literature review. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-024-08767-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-024-08767-x