Abstract

Purpose

Numerous studies have demonstrated effectiveness for acupuncture in the treatment of seasonal allergic rhinitis (SAR). However, the underlying mechanism remains still unclear.

Methods

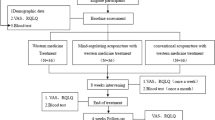

29 SAR patients were recruited from a large randomized, controlled trial investigating the efficacy of acupuncture in SAR. 16 patients were treated by acupuncture plus rescue medication (RM, cetirizine), 6 patients received sham acupuncture plus RM and 8 patients RM alone over 8 weeks. Patients were blinded to the allocation to real or sham acupuncture. At baseline and different time-points during intervention, plasma and nasal concentration of mediators of various biological functions were determined in addition to validated disease-specific questionnaires.

Results

The concentration of biomarkers related to the Th1-, Th2-, and Treg-cluster was not changed in patients who received acupuncture, in neither plasma nor nasal fluid. However, with respect to eotaxin and some unspecific pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1b, IL-8, IP-10, MIP-1b, MCP-1), acupuncture led to a, partially significantly, lower nasal concentration than sham acupuncture or RM. Furthermore, the nasal symptom score was significantly reduced in patients only after real acupuncture.

Conclusion

In SAR, acupuncture reduces the intranasal unspecific inflammation, but does not seem to act immunologically on the Th1–Th2-imbalance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Acupuncture, as a complementary and integrative medicine therapy, aims to target certain specific acupoints to improve the treatment of various diseases [1]. As acupuncture is a rather safe therapy, many patients try to alleviate various symptoms through acupuncture. Among patients with allergic rhinitis (AR), the estimated lifetime prevalence of acupuncture use even ranges at about 19% [2].

Numerous reviews and meta-analysis have demonstrated effectiveness for acupuncture in the treatment of both seasonal and perennial AR [3,4,5]. Due to its lasting and stable efficacy in alleviating AR symptoms, acupuncture is widely used with this indication not only in China, but all across the world [6]. As a consequence, acupuncture is even included as a therapy option in the United States’ current clinical guideline for ENT diseases [7].

Despite a variety of high-quality trials confirming efficacy of acupuncture in AR [8,9,10,11,12], acupuncture is often criticised as “unproven” [13], as strong evidence of the underlying mechanism is still missing. Most studies focus on semi-objective variables as rescue medication use or symptom scores or disease-related quality of life. Objective parameters such as changes in cytokine levels are mainly investigated in animal studies [14,15,16,17]. In the literature, only very few trials can be found analysing the molecular basis of acupuncture in AR in humans. One study on differential gene expression in the peripheral blood of patients with AR before and after acupuncture treatment suggest that the balance between T-helper 1 (Th1) and T-helper 2 (Th2) cell-derived pro-inflammatory versus anti-inflammatory cytokines might be improved by acupuncture treatment [18]. However, no control group was included in this study. In another trial, some interleukin (IL) titers were determined demonstrating a tendency of an increasing IL-10 value in the acupuncture group vs. an antihistamine treated group [19]. Although this result indicates the probability of an immunomodulatory effect [19], the evidence is limited due to a missing sham-acupunctured control group. To our knowledge, there is only one randomized, sham-controlled trial of acupuncture for persistent allergic rhinitis in adults investigating a possible modulation of mucosal immune responses [20]: after acupuncture, allergen specific IgE for house dust mite and the pro-inflammatory substance P were down-regulated, whereas all other measured mediators remained stable in saliva and plasma. Nasal secretion, which could reflect changes in mucosal immune response better than saliva, was not analysed.

As acupuncture—despite its positive clinical evidence—will only be fully accepted as treatment of allergic diseases, if a specific mechanism is proved [21], we initiated the present sub-study of a large three-armed randomised controlled trial of acupuncture in seasonal allergic rhinitis (ACUSAR) which had shown a positive outcome of acupuncture compared to sham acupuncture and to rescue medication alone [9, 22]. The aim of the sub-study was to investigate the immediate and prolonged immunomodulatory effects of acupuncture in seasonal AR by determining various mediators in nasal fluid and plasma.

Patients and methods

The underlying data of the present study originate from the ACUSAR trial, a three-armed, randomised, controlled multicenter study on the efficacy of acupuncture in seasonal allergic rhinitis (SAR) with regard to rhinitis-related quality of life and rescue medication score. Further details of the study protocol and the results have been published previously [9, 22]. In a sub-study, which was performed at the study center at the Technical University Munich, blood and nasal discharge was taken to investigate the effect of the interventions on various cytokine and chemokine profiles.

The ACUSAR trial as well as the present sub-study were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Written informed consent was provided by all study participants. The study protocol of the ACUSAR trial and of the present sub-study was authorised by the ethics review committee of the Technical University Munich.

Study population

The inclusion criteria were patients aged 16–45 years, suffering from moderate to severe SAR (according to ARIA criteria) lasting for at least 2 years. Sensitization towards birch or grass had been proven; in cases of doubt with regard to the clinical relevance of sensitization, nasal allergen challenges have been performed. The exclusion criteria were perennial AR, allergic asthma, a history of anaphylactic reactions, moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, autoimmune disorders, severe chronic inflammatory diseases, hypersensitivity to cetirizine or related drugs, specific immunotherapy during the last 3 years or planned in the next 2 years, pregnancy or breastfeeding, previous acupuncture treatment for SAR, and any further use of complementary and alternative medicine.

Randomisation and interventions

In the beginning of the pollen season and after the appearance of first SAR symptoms, the patients started to participate in the study. For randomisation, a 2:1:1 allocation ratio was used and carried out through a centralised telephone randomisation procedure. The patients receiving acupuncture were blinded to the treatment allocation (acupuncture or sham acupuncture) for the entire study.

The patients of the acupuncture group received in sum 12 sessions of semi-standardized acupuncture, 2 sessions per week during the first 4 weeks and one session weekly during the further 4 weeks of study. The patients were treated by trained physicians with additional extensive acupuncture training at four obligatory basic Chinese medicine acupuncture points (LI4, LI11, LI20 bilaterally and Yintang), at least three of eight facultative basic points (Bitong, GB20, LR3, LU7, ST36, SP6, TE17 or BL13) and at least three additional points. The patients of the sham acupuncture group were treated according to the same time protocol, however, they received superficial needling without provoking the Deqi-sensation or at pre-defined non-acupuncture points without any link to the disease.

The rescue medication (RM) group did not receive any acupuncture. All patients, regardless of their allocation, were allowed to take a second-generation oral antihistamine (cetirizine) up to twice daily. Further details are described in the study protocol previously [22].

Data collection

Nasal fluid was collected at baseline (before the first acupuncture session), directly after the first acupuncture session, at week 4 (day 28) and week 8 (day 56). Blood samples were taken at baseline, on day 28 and on day 56.

For collecting of nasal secretion, the cotton wool method as described by Rasp et al. [23] was carried out with minor modifications according to Kramer et al. [24]. Nasal fluid was gained by introducing small cone-shaped cotton wool pieces (absorbent cotton, Hartmann, Heidenheim/Brenz, Germany) with a length of about 30 mm and a diameter of about 4–6 mm into the middle meatus of the nose. After 20 min, the cotton wool pieces were taken out and subsequently centrifuged (+ 4 °C, 3000 g) on a sieve for 10 min. The hereby gained nasal secretions were frozen at − 18 °C.

Furthermore, within the scope of the ACUSAR study, patients reported on changes in their symptoms and medication need which was assessed in a standardized manner using the Rhinitis Quality of Life Questionnaire (RQLQ) and the Rescue Medication Score (RMS).

Biochemical and immunological methods

After dilution to 1:5, nasal fluids were analysed for the concentration of various, below-mentioned cytokines using a human cytokine 27-plex panel according to manufacturer`s instructions (Bio-Plex Pro Human Cytokine Standard 27-Plex, Group I, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, California, USA). This assay uses fluorescently labelled polystyrene beads which are conjugated to capture antibodies directed to the cytokines. After washing, the fluorescently addressed detection antibody forms an immunoassay with the cytokine. For analysis, the fluorochromes are excited by two lasers: one for classifying each bead, the other for quantifying the amount of bound substrate [25]. The same procedure was performed with plasma, however, after dilution to 1:4. The detection threshold was 0.5 pg/ml. The determined cytokines were eotaxin as eosinophilic marker, IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 as part of the Th2-cluster, IL2, IL-12 and IFN-gamma as markers of the Th1-cluster, IL-10 as representative of the Treg-Cluster, and unspecific inflammatory markers such as IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-17, TNF-alpha, MCP-1, MIP-1β and IP-10.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SigmaStat (Jandel Corp., San Rafael, CA, USA). For descriptive statistics, we used median values with range due to the small sample sizes.

Almost all data failed normality testing (Shapiro–Wilk); therefore, non-parametric tests have been used: The Mann–Whitney rank sum test was carried out to compare concentrations between different cohorts at the same time point (inter-group comparison). The Friedman analysis was used to compare the concentration at different time-points among one study group (intra-group comparison). A p-value ≤ 0.05 was judged significant.

Results

Characterization of the study population

29 patients meeting the above-mentioned inclusion criteria were included in this sub-study, which was performed at the Technical University Munich in cooperation with the medical center of the University Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin. According to allocation ratio 2:1:1 of the ACUSAR trial, 15 patients received real acupuncture plus RM, 6 patients sham acupuncture plus RM and further 8 patients RM alone. The seventh patient receiving sham acupuncture plus RM within the ACUSAR study refused the participation in the sub-study.

Demographic and clinical data of the three study cohorts are given in detail in Table 1, separated according to the treatment arm of acupuncture plus RM, sham acupuncture plus RM and RM alone. Concerning most parameters, the three groups were well comparable.

Concentration of biomarkers

In plasma as well as in nasal secretion, the concentration of many determined biomarkers was below the cut-off value (IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, IL-12 and IL-17). For IL-13, almost all measured concentrations were below the cut-off value. Therefore, no meaningful conclusion could be drawn with regard to a potential effect on these markers by acupuncture.

Concerning all other measured cytokines, we found levels above the cuff-off-level, at least in nasal secretion. In general, the concentration of most cytokines was significantly higher locally in nasal fluid than measured systemically in the plasma (concentration in plasma vs. in nasal secretion: median p value 0.002, range from < 0.001 to 0.310).

Concentration of biomarkers in plasma

Regardless of the concerned mediator and its baseline level in plasma, we did not register any statistically significant changes in plasma concentration within one treatment arm at different time points during intervention. Data are given in the Supplement (Suppl. Table 1).

Due to the large individual variation range of cytokine concentrations, the median change from baseline concentration was used for inter-group comparison: However, no statistically significant difference could be observed between the three treatment groups, which is displayed in the Supplement (Suppl. Table 2).

Thus, no intervention significantly affected the plasma level of any of the analysed biomarkers, regardless of its biological function.

Concentrations of biomarkers in nasal secretion

Similarly, as in plasma, no clear trend could be observed locally in nasal concentrations of biomarkers related to the Th1-, Th2-, and Treg-cluster. For some cytokines belonging to these clusters, nasal concentrations were below the cut-off (IL-4, IL-5, IL-12, IL-10). In those cytokines of which the level was above the cut-off (e.g. IL-13 as Th2-marker or IFN-gamma as Th1-marker), no relevant consistent change could be found while intervention in any treatment arm.

In the group of unspecific pro-inflammatory mediators, IL-2 and IL-17 remained below the cut-off, whereas TNF-alpha and IL-6 had values above the cut-off, but did not show any uniform trend of change in concentration throughout intervention.

However, there was a similar trend with respect to some other biomarkers of unspecific inflammation, namely IL-1β, IL-8, IP-10 and MCP-1, and less pronounced MIP-1β and IL-7. As displayed by the red graphs in Fig. 1, the nasal concentration of most analysed pro-inflammatory mediators increased from baseline to the end of intervention in patients treated by sham acupuncture and rescue medication alone. In patients undergoing real acupuncture, however, the final nasal level of inflammatory cytokines was relatively similar to baseline values.

Percentage change from baseline nasal concentration of various pro-inflammatory cytokines throughout intervention consisting of a acupuncture, b sham acupuncture and c rescue medication. The red graphs show the change of nasal mediator level from baseline to the end of intervention. Patients treated by sham acupuncture (b) or rescue medication (c) experienced an increase in nasal concentration of most pro-inflammatory mediators. Patients treated by real acupuncture (a), however, had a rather equal nasal concentration of most inflammatory cytokines at the end of treatment. The grey graphs show the course of each individual analysed cytokine, which appears rather uniform in patients undergoing real acupuncture—with an initial decrease after the first session of acupuncture, followed by an increase and finally a reduction to near baseline

Furthermore, as shown by the grey graphs in Fig. 1, the course of nasal concentrations of the individual mediators resemble each other, particularly in the acupuncture group: directly after the first session of treatment, all patients had a lower nasal cytokine level than at baseline, especially patients treated with real acupuncture. This initial decrease was less frequently observed in patients receiving sham acupuncture or RM alone. Four weeks later, under ongoing therapy, the concentration of unspecific inflammatory markers increased in almost all groups, however, at discrepant amounts. At the latest time point of measurement, after 8 weeks of intervention, the nasal level of pro-inflammatory cytokines was the highest among patients with sham acupuncture, except for MIP-1β.

Figure 2 displays the effect of the three treatments (acupuncture, sham acupuncture and rescue medication alone) on the nasal concentration of each affected pro-inflammatory mediator.

With respect to IL-1β, IL-8, IP-10, MCP-1 and MIP-1β, the final nasal concentration was lower after acupuncture compared to sham acupuncture, even reaching statistical significance concerning IL-1β. RM led to lower pro-inflammatory cytokine levels than sham acupuncture, with the exception of MIP-1β.

The characteristic trend, which was registered in the nasal concentration of several unspecific pro-inflammatory cytokines mentioned above, could be seen regarding eotaxin, a biomarker of eosinophilia, too (see Table 2). Directly after the first treatment, as displayed in Fig. 3, the nasal concentration of eotaxin was reduced in all treatment arms, however, particularly after real acupuncture. At the subsequent time-points of measurements, the nasal level of eotaxin increased again. After 12 sessions of real acupuncture, the final eotaxin level was still lower than at baseline, whereas both alternative treatments, sham acupuncture or RM alone, led to eotaxin concentrations rather equal to baseline. As seen in IL-1β, the difference in final nasal eotaxin concentration was statistically significant between real acupuncture and sham acupuncture (p = 0.017).

Median change to baseline nasal concentration of eotaxin throughout intervention in acupuncture (bold black line), sham acupuncture (white triangles) and RM (white squares). Directly after the first treatment, all patients had a lower nasal concentration of eotaxin compared to baseline, however particular after real acupuncture. At the subsequent two time-points, the nasal eotaxin level had increased. After 8 weeks of intervention, patients treated by real acupuncture had a significantly lower nasal eotaxin concentration than patients having undergone sham acupuncture

The tendency, that most pro-inflammatory cytokine levels were the lowest after real acupuncture and the highest after sham acupuncture, whereas RM let to less or more lower concentrations than sham acupuncture, was accompanied by a similar trend in the quality of life data, as given in Table 3.

Discussion

In the literature, there is an increasing number of studies revealing effectiveness of acupuncture in treating various diseases. Not least, the ACUSAR trial, which the data of this study originate from, could show a significant improvement in disease-specific quality of life and antihistamine use in patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis after 8 weeks of acupuncture compared with sham acupuncture or rescue medication alone [9]. However, the underlying mechanisms still remains speculative. As allergies are caused by an imbalance between Th1- and Th2-cell response, one possible point of action could be a modulation of the Th1/Th2-balance by acupuncture. However, our analysis did not reveal any acupuncture-related significant change in concentrations of cytokines associated to the Th1- or Th2-pathway, neither locally in nasal fluid nor systemically in plasma. When looking into the literature, a decrease in IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 after acupuncture could be seen in animal experiments, namely in rats suffering from allergic rhinitis [26]. Two studies on humans with AR, however, revealed constant concentrations of IL-4 in the blood [19, 20]. However, there is, to our knowledge, no published study analysing nasal fluid in this context. Concerning total and specific IgE which are considered as representative markers of allergy, too, controversial results have been found [19, 20, 27]. However, even in a study revealing a statistically significant change in specific IgE against mites after acupuncture, the decrease (from 18 to 16 kU/l) is too low to expect a clinical significance of the finding [20].

Also with regard to the Th1-pathway, controversial results can be found in the literature. Whereas gene expression profiles in patients with AR before and after acupoint herbal plaster have shown an up-regulation of the Interferon (IFN)-signalling [28], the concentration of IFN-γ remained constant throughout acupuncture treatment in humans with AR in other trials [19, 20, 27].

One could go into detail and analyse the potential limitations of the various trials in order to rate the validity of each study and its result. However, it appears meaningful to us that acupuncture does not specifically affect the Th1/Th2-pathway, since acupuncture is known to improve many different disease entities suggesting a more general physiological mechanism of acting.

This suggestion is further underlined by our observation that the plasma and nasal level of IL-10, a marker of the Treg-cluster, remained constant despite acupuncture. IL-10 is able to hinder the histamine release of activated mast cells [29] and can be regarded as a biomarker reflecting the effectiveness of the anti-allergic therapy [30]. Our finding that acupuncture improved the disease-specific quality of life without affecting the IL-10 level, can be regarded as further hint that acupuncture does not act as specific anti-allergic therapy, but throughout a different mechanism.

One possible mode of action could be a reduction in unspecific inflammation. Some biomarkers of unspecific inflammation, such as IL-2 and IL-17, remained below the cut-off value, whereas the concentration of TNF-alpha and IL-6 were above the cut-off, but did not show any relevant change in concentration throughout intervention. With respect to IL-6, our finding is confirmed by another study [31].

Regarding all other assessed cytokine profiles, which are related to unspecific inflammation (IL-1β, IL-7, IL-8, IP-10, MCP-1 and MIP-1β), a general trend could be registered: directly after the first session of treatment, a decrease in cytokine level was found compared to baseline, especially after real acupuncture. One potential explanation could be a dilution effect due to a treatment-associated rhinorrhea. On the other hand, a small decrease was also seen in the two other groups—this result might be due to a local irritation of the nasal mucosa by the sampling of nasal fluid twice within a few hours.

Following this initial decrease, concentrations of most pro-inflammatory cytokines increased again and finally reached levels above the baseline value. This general increase during the intervention period is probably due to the ongoing pollen season enhancing the inflammation over time. Furthermore, as most patients were polysensitized to more allergens than birch and grass, most patients will have been exposed to a higher number of relevant allergen sources at the end of the study than in the beginning.

At the latest time point of measurement, after 8 weeks of intervention, the level of pro-inflammatory cytokines was the highest among the sham-acupunctured patients followed by the RM group. Patients who had been treated by real acupuncture for 8 weeks, had the lowest levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines. This partially statistically significant finding could be seen as confirmation that real acupuncture leads to a reduction of unspecific inflammation. As this treatment effect was only seen after real acupuncture, although patients were blinded to real acupuncture and sham acupuncture, this result cannot be regarded as placebo effect. One might speculate that the anti-inflammatory effect of acupuncture is of clinical relevance, as it was accompanied by a statistically significant improvement in the nasal symptom score of RQLQ, which was only experienced by patients receiving acupuncture.

Still, it remains to discuss why patients, who had received sham acupuncture, had higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines than patients treated with RM only. This discrepancy is not statistically significant, though it appears relevant as it goes along with the same trend in the quality of life results: in the present sub-study, patients treated by RM solely had a better nasal and overall quality of life compared to sham-acupunctured patients. At first sight, it appeared likely that this discrepancy in the level of inflammatory cytokines and in the quality of life between sham acupuncture and RM alone is due to a discrepant antihistamine use. Antihistamines are an effective drug for reducing inflammation and cytokine release. That is why histamine receptor antagonists are currently widely discussed in the context of COVID-19 as they might reduce the histamine-mediated pulmonary cytokine storm [32]. In the context of AR, it is proven that histamine upregulates the expression of various chemokines including MCP-1 and eotaxin in the nasal mucosa [33]. This increase can be inhibited by a second-generation antihistamine [33, 34], which also reduces the concentration of IP-10, MIP-1β, IL-8 [35] and IL-1β [36]. Indeed, the ACUSAR study had shown that the percentage of patients using RM and the taken dose was higher among patients receiving sham acupuncture than among patients without any acupuncture [37]. However, when focussing on individual patients in our study center, we could not find a clear correlation between rescue medication score and cytokine level.

With regard to non-allergic diseases, several studies could demonstrate an anti-inflammatory effect by acupuncture in animals, for example in rats suffering from peritonitis [38] or M. Alzheimer [39]. Human trials, which investigate a potential anti-inflammatory effect of manual acupuncture, are rare. Nevertheless, in one recent study, acupuncture has been found to reduce the serum concentration of IL-1β in patients suffering from knee osteoarthritis [40]. Furthermore, in the context of the therapeutic effect of acupuncture on type I hypersensitivity itch or histamine-induced itch, it has been speculated that the influence on itch is probably because of effects on inflammation (probably neurogenic inflammation) and probably not specifically antipruritic [41, 42].

With regard to eotaxin, our literature search revealed only one human study demonstrating a constant plasma level of eotaxin after 12 sessions of acupuncture in persistent AR [20] which is in line with our observation.

However, a direct comparison of our findings in nasal fluid with the literature is not possible, as the present study is to our knowledge the first published analysis of nasal fluid in the context of acupuncture in SAR.

There are several limitations in this study: the most relevant limitation is the small sample size of this sub-study, especially in both control groups due to the allocation ratio of the randomisation. Furthermore, the concentration of mediators in nasal secretion varies a lot among individuals prohibiting a comparison of concrete values. Consequently, the use of median change from baseline was required to allow comparability. In addition, the exposure to allergens was not standardized as it did not follow an experimental design, but was caused by natural airborne pollen of which the concentration and composition may differ locally.

Furthermore, the determination of other mediators, especially the local concentration of Substance P and (specific) IgE, would have been interesting. However, the volume of nasal fluid varies individually by a large amount. In most patients, there was too less material for a wider repertoire of measurements, especially as the determination of IgE by ImmunoCAP needs a rather large sample volume.

Another critical point might be that, according to the principle of segmental innervation by Head [43], the skin is linked to the inner organs. Although sham exposure did not include needling in the head and neck region penetrating sham exposure cannot be regarded as complete placebo treatment as an effect on the immune system is not fully excluded.

Despite several limitations, the present data are based on a study design and methodology of very high quality and represent, to our knowledge, the first analysis of nasal fluid in the context of acupuncture treating allergic rhinitis. Due to these advantages, the data are to be considered as an important step towards a better understanding of the acting mechanism of acupuncture in AR.

In the future, further investigations on the potential mechanism of acupuncture are crucial. A promising target might be mediators of the neuroendocrine pathways, as autonomic dysfunction has been shown to play an important role in the induction and aggravation of AR [44]. Furthermore, another sub-study of the ACUSAR trial has shown that acupuncture partially normalized SAR-related alterations of the autonomic function [45]. When focussing on rather unexplored autonomic neuroendocrine processes, Substance P, a pro-inflammatory neuropeptide, might be an interesting target to analyse as it might trigger the acupuncture-induced signalling [46]. Furthermore, Substance P has been deeply investigated in the context of idiopathic rhinitis in the past [47] and in recent times [48]. However, it might also play an essential role in AR [49].

In sum, our sub-study of the large ACUSAR trial reveals an inhibition of nasal pro-inflammatory cytokines in patients with SAR during real acupuncture. This anti-inflammatory effect by real acupuncture was not achieved by sham acupuncture. An immunological effect on the Th1/Th2 balance, however, could not be seen. Consequently, the effectiveness of acupuncture in the treatment of allergies does not seem to be caused by a specific immunologic anti-allergic mechanism. Instead, an unspecific anti-inflammatory effect appears to be more likely. It appears conceivable, that an anti-inflammatory effect might even explain the continuing treatment effect by acupuncture, as seen in the ACUSAR trial even in the subsequent pollen season although no further treatment had been applied after the end of the preceding pollen season.

The presented sub-study emphasizes the conduction of larger trials on this mechanism of acupuncture, especially as an anti-inflammatory effect might further explain the positive treatment effect of acupuncture on various non-allergic diseases.

References

Sundman E, Olofsson PS (2014) Neural control of the immune system. Adv Physiol Educ 38:135–139

Krouse JH, Krouse HJ (1999) Patient use of traditional and complementary therapies in treating rhinosinusitis before consulting an otolaryngologist. Laryngoscope 109:1223–1227

Taw MB, Reddy WD, Omole FS, Seidman MD (2015) Acupuncture and allergic rhinitis. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 23:216–220

Feng S, Han M, Fan Y, Yang G, Liao Z, Liao W, Li H (2015) Acupuncture for the treatment of allergic rhinitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Rhinol Allergy 29:57–62

Pfab F, Schalock PC, Napadow V, Athanasiadis GI, Huss-Marp J, Ring J (2014) Acupuncture for allergic disease therapy—the current state of evidence. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 10:831–841

Mi JP, He P, Shen F, Yang X, Zhao MF, Chen XY (2020) Efficacy of acupuncture at the sphenopalatine ganglion in the treatment of persistent allergic rhinitis. Medical acupuncture 32:90–98

Seidman MD, Gurgel RK, Lin SY, Schwartz SR, Baroody FM, Bonner JR, Dawson DE, Dykewicz MS, Hackell JM, Han JK, Ishman SL, Krouse HJ, Malekzadeh S, Mims JW, Omole FS, Reddy WD, Wallace DV, Walsh SA, Warren BE, Wilson MN, Nnacheta LC (2015) Clinical practice guideline: allergic rhinitis executive summary. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg Off J Am Acad Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 152:197–206

Brinkhaus B, Hummelsberger J, Kohnen R, Seufert J, Hempen CH, Leonhardy H, Nogel R, Joos S, Hahn E, Schuppan D (2004) Acupuncture and chinese herbal medicine in the treatment of patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis: a randomized-controlled clinical trial. Allergy 59:953–960

Brinkhaus B, Ortiz M, Witt CM, Roll S, Linde K, Pfab F, Niggemann B, Hummelsberger J, Treszl A, Ring J, Zuberbier T, Wegscheider K, Willich SN (2013) Acupuncture in patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 158:225–234

Choi SM, Park JE, Li SS, Jung H, Zi M, Kim TH, Jung S, Kim A, Shin M, Sul JU, Hong Z, Ji** Z, Lee S, Liyun H, Kang K, Baoyan L (2013) A multicenter, randomized, controlled trial testing the effects of acupuncture on allergic rhinitis. Allergy 68:365–374

Mi J, Chen X, Lin X, Guo J, Chen H, Wei L, Hong H (2018) Treatment of persistent allergic rhinitis via acupuncture at the sphenopalatine acupoint: a randomized controlled trial. Trials 19:28

Zhang L, Jiang L, Cheng K, Fu JH, Jian-Wu S, Wang KJ, Song YJ, Meng XZ, Xu ZX, Chen LH, Guo MM, Zhang LJ, Zhang LL, Shi DZ (2020) A multicenter randomized controlled pilot trial testing the efficacy and safety of pterygopalatine fossa puncture using one acupuncture needle for moderate-to-severe persistent allergic rhinitis. Evid-Based Complement Altern Med eCAM 2020:2975974

Agnihotri NT, Greenberger PA (2019) Unproved and controversial methods and theories in allergy/immunology. Allergy Asthma Proc 40:490–493

Wang Z, Lu M, Ren J, Wu X, Long M, Chen L, Chen Z (2019) Electroacupuncture inhibits mast cell degranulation via cannabinoid cb2 receptors in a rat model of allergic contact dermatitis. Acupunct Med J Br Med Acupunct Soc 37:348–355

Wang Y, Hou XR, Li LH, Zhang Y, Yang H, Liang X, Lu YW (2019) acupoint injection improves allergic rhinitis by balancing th17/treg in allergic rhinitis rats. Zhen Ci Yan Jiu Acupunct Res 44:276–281

Liu YL, Zhang LD, Ma TM, Song ST, Liu HT, Wang X, Li N, Yang C, Yu S (2018) Feishu acupuncture inhibits acetylcholine synthesis and restores muscarinic acetylcholine receptor m2 expression in the lung when treating allergic asthma. Inflammation 41:741–750

Wang Z, Yi T, Long M, Ding F, Ouyang L, Chen Z (2018) Involvement of the negative feedback of il-33 signaling in the anti-inflammatory effect of electro-acupuncture on allergic contact dermatitis via targeting microrna-155 in mast cells. Inflammation 41:859–869

Shiue HS, Lee YS, Tsai CN, Hsueh YM, Sheu JR, Chang HH (2008) DNA microarray analysis of the effect on inflammation in patients treated with acupuncture for allergic rhinitis. J Altern Complement Med (New York, NY) 14:689–698

Hauswald B, Dill C, Boxberger J, Kuhlisch E, Zahnert T, Yarin YM (2014) The effectiveness of acupuncture compared to loratadine in patients allergic to house dust mites. J Allergy 2014:654632

McDonald JL, Smith PK, Smith CA, Changli Xue C, Golianu B, Cripps AW (2016) Effect of acupuncture on house dust mite specific ige, substance p, and symptoms in persistent allergic rhinitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol Off Publ Am Coll Allergy Asthma Immunol 116:497–505

Brinkhaus B, Ortiz M, Dietzel J, Willich S (2020) acupuncture for pain and allergic rhinitis-from clinical experience to evidence. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 63:561–569

Brinkhaus B, Witt CM, Ortiz M, Roll S, Reinhold T, Linde K, Pfab F, Niggemann B, Hummelsberger J, Irnich D, Wegscheider K, Willich SN (2006) Acupuncture in seasonal allergic rhinitis (acusar)–design and protocol of a randomised controlled multi-centre trial. Forschende Komplementarmedizin 2010(17):95–102

Rasp G, Thomas PA, Bujia J (1994) Eosinophil inflammation of the nasal mucosa in allergic and non-allergic rhinitis measured by eosinophil cationic protein levels in native nasal fluid and serum. Clin Exp Allergy J Br Soc Allergy Clin Immunol 24:1151–1156

Kramer MF, Burow G, Pfrogner E, Rasp G (2004) In vitro diagnosis of chronic nasal inflammation. Clinical and Exp Allergy J Br Soc Allergy Clin Immunol 34:1086–1092

Vignali DA (2000) Multiplexed particle-based flow cytometric assays. J Immunol Methods 243:243–255

Tu W, Chen X, Wu Q, Ying X, He R, Lou X, Yang G, Zhou K, Jiang S (2020) Acupoint application inhibits nerve growth factor and attenuates allergic inflammation in allergic rhinitis model rats. J Inflamm (Lond, Engl) 17:4

Rao YQ, Han NY (2006) Therapeutic effect of acupuncture on allergic rhinitis and its effects on immunologic function. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu Chin Acupunct Moxibustion 26:557–560

Shiue HS, Lee YS, Tsai CN, Chang HH (2016) Treatment of allergic rhinitis with acupoint herbal plaster: an oligonucleotide chip analysis. BMC Complement Altern Med 16:436

Royer B, Varadaradjalou S, Saas P, Guillosson JJ, Kantelip JP, Arock M (2001) Inhibition of ige-induced activation of human mast cells by il-10. Clin Exp Allergy J Br Soc Allergy Clin Immunol 31:694–704

Woodfolk JA (2006) Selective roles and dysregulation of interleukin-10 in allergic disease. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 6:40–46

Petti FB, Liguori A, Ippoliti F (2002) Study on cytokines il-2, il-6, il-10 in patients of chronic allergic rhinitis treated with acupuncture. J Tradit Chin Med Chung i tsa chih ying wen pan 22:104–111

Hogan Ii RB, Hogan Iii RB, Cannon T, Rappai M, Studdard J, Paul D, Dooley TP (2020) Dual-histamine receptor blockade with cetirizine—famotidine reduces pulmonary symptoms in covid-19 patients. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 63:101942

Fujikura T, Shimosawa T, Yakuo I (2001) Regulatory effect of histamine h1 receptor antagonist on the expression of messenger rna encoding cc chemokines in the human nasal mucosa. J Allergy Clin Immunol 107:123–128

Wang J, Zhao Y, Yan X (2019) Effects of desloratadine citrate disodium on serum immune function indices, inflammatory factors and chemokines in patients with chronic urticaria. J Coll Phys Surg Pak JCPSP 29:214–217

Canonica GW, Blaiss M (2011) Antihistaminic, anti-inflammatory, and antiallergic properties of the nonsedating second-generation antihistamine desloratadine: a review of the evidence. World Allergy Org J 4:47–53

Plekhova NG, Eliseeva EV, Dubnyak IN (2021) Antihistamines modulate functional activity of macrophages. Bull Exp Biol Med 170:759–762

Adam D, Grabenhenrich L, Ortiz M, Binting S, Reinhold T, Brinkhaus B (2018) Impact of acupuncture on antihistamine use in patients suffering seasonal allergic rhinitis: Secondary analysis of results from a randomised controlled trial. Acupunct Med J Br Med Acupunct Soc 36:139–145

Ramires CC, Balbinot DT, Cidral-Filho FJ, Dias DV, Dos Santos AR, da Silva MD: Acupuncture reduces peripheral and brainstem cytokines in rats subjected to lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation. Acupunct Med J Br Med Acupunct Soc 2020:964528420938379.

Jang JH, Yeom MJ, Ahn S, Oh JY, Ji S, Kim TH, Park HJ (2020) Acupuncture inhibits neuroinflammation and gut microbial dysbiosis in a mouse model of parkinson’s disease. Brain Behav Immun 89:641–655

Shi GX, Tu JF, Wang TQ, Yang JW, Wang LQ, Lin LL, Wang Y, Li YT, Liu CZ (2020) Effect of electro-acupuncture (ea) and manual acupuncture (ma) on markers of inflammation in knee osteoarthritis. J Pain Res 13:2171–2179

Pfab F, Huss-Marp J, Gatti A, Fuqin J, Athanasiadis GI, Irnich D, Raap U, Schober W, Behrendt H, Ring J, Darsow U (2010) Influence of acupuncture on type i hypersensitivity itch and the wheal and flare response in adults with atopic eczema—a blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Allergy 65:903–910

Pfab F, Hammes M, Bäcker M, Huss-Marp J, Athanasiadis GI, Tölle TR, Behrendt H, Ring J, Darsow U (2005) Preventive effect of acupuncture on histamine-induced itch: a blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol 116:1386–1388

Head H (1898) Die sensibilitätsstörungen der haut bei viszeralerkrankungen. August Hirschwald Verlag, Berlin

Sarin S, Undem B, Sanico A, Togias A (2006) The role of the nervous system in rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 118:999–1016

Ortiz M, Brinkhaus B, Enck P, Musial F, Zimmermann-Viehoff F (2006) Autonomic function in seasonal allergic rhinitis and acupuncture - an experimental pilot study within a randomized trial. Forschende Komplementarmedizin 2015(22):85–92

Fan Y, Kim DH, Gwak YS, Ahn D, Ryu Y, Chang S, Lee BH, Bills KB, Steffensen SC, Yang CH, Kim HY (2021) The role of substance p in acupuncture signal transduction and effects. Brain Behav Immun 91:683–694

Anggård A (1979) Vasomotor rhinitis–pathophysiological aspects. Rhinology 17:31–35

Van Gerven L, Alpizar YA, Wouters MM, Hox V, Hauben E, Jorissen M, Boeckxstaens G, Talavera K, Hellings PW: Capsaicin treatment reduces nasal hyperreactivity and transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily v, receptor 1 (trpv1) overexpression in patients with idiopathic rhinitis. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 2014;133:1332–1339, 1339 e1331–1333.

Kavut AB, Kalpaklıoğlu F, Atasoy P (2013) Contribution of neurogenic and allergic ways to the pathophysiology of nonallergic rhinitis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 160:184–191

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Liliana Cifuentes Guiterrez, MD, for her assistance in collecting nasal fluids. Furthermore, we are grateful for the excellent technical support from Gabi Bärr, technician in Munich, and from Margit Cree in Berlin.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The ACUSAR trial was financially supported by the DFG (German Research Foundation, grant WI 957/16–1). The present sub-study had no external funding source.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DG designed the study, acquired, analysed and interpreted all data and drafted the article. FP designed the study, acquired all samples, was substantially involved in analysis and interpretation of data and in critically revising the article. MO and SB participated in the study design, acquisition and interpretation of data and revised the article critically. BB and MG designed the study, were substantially involved in acquisition and interpretation of data, helped to draft the manuscript and revised it critically. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that there are no financial or non-financial interests that are directly or indirectly related to the work submitted for publication.

Ethics approval

The ACUSAR trial as well as the present sub-study were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki Good Clinical Practice guidelines

Informed consent

Written informed consent was provided by all study participants. The study protocol of the ACUSAR trial and of the present sub-study was authorised by the ethics review committee of the Technical University Munich.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gellrich, D., Pfab, F., Ortiz, M. et al. Acupuncture and its effect on cytokine and chemokine profiles in seasonal allergic rhinitis: a preliminary three-armed, randomized, controlled trial. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 279, 4985–4995 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-022-07335-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-022-07335-5