Abstract

To depict the spectrum of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in Egypt in relation to other universal studies to provide broad-based characteristics to this particular population. This work included 10,364 adult RA patients from 26 specialized Egyptian rheumatology centers representing 22 major cities all over the country. The demographic and clinical features as well as therapeutic data were assessed. The mean age of the patients was 44.8 ± 11.7 years, disease duration 6.4 ± 6 years, and age at onset 38.4 ± 11.6 years; 209 (2%) were juvenile-onset. They were 8750 females and 1614 males (F:M 5.4:1). 8% were diabetic and 11.5% hypertensive. Their disease activity score (DAS28) was 4.4 ± 1.4 and health assessment questionnaire (HAQ) 0.95 ± 0.64. The rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) were positive in 73.7% and 66.7% respectively. Methotrexate was the most used treatment (78%) followed by hydroxychloroquine (73.7%) and steroids (71.3%). Biologic therapy was received by 11.6% with a significantly higher frequency by males vs females (15.7% vs 10.9%, p = 0.001). The least age at onset, F:M, RF and anti-CCP positivity were present in Upper Egypt (p < 0.0001), while the highest DAS28 was reported in Canal cities and Sinai (p < 0.0001). The HAQ was significantly increased in Upper Egypt with the least disability in Canal cities and Sinai (p = 0.001). Biologic therapy intake was higher in Lower Egypt followed by the Capital (p < 0.0001). The spectrum of RA phenotype in Egypt is variable across the country with an increasing shift in the F:M ratio. The age at onset was lower than in other countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic systemic autoimmune disease primarily affecting small synovial joints usually symmetrically. Symptoms for more than 6 months establish the diagnosis of RA [1]. An intricate network of cytokines and cells trigger synovial cell proliferation and cause damage to both cartilage and bone [2].

Alone the laboratory test for RA cannot confirm a diagnosis that is commonly challenging. A complete clinical approach is necessary to diagnose and avoid debilitating joint damage [1]. Yet, auto-antibodies signify a hallmark of RA, with the rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-cyclic citrullinated (anti-CCP) peptides being the most acknowledged. Seropositive patients present a certain disease course. With the recent improvements in diagnosis and the discovery of new autoantibodies, the group of seronegative patients is persistently shrinking [3]. Using applicable disease activity measures can help in clinical practice to take on treat-to-target strategies in RA patients [4]. There has been a rising importance for the early and demanding diagnosis and treatment of RA with the goal of reducing disability and mortality [5].

To improve the clinical outcome in RA, various therapeutic approaches are required [1], although current management recommendations may still support a 'one-size-fits-all' treatment strategy [6]. Early treatment with disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) is standard, yet many patients progress to disability with substantial morbidity over time [1]. The arrival of biologics has changed the treatment of RA due to their remarkable impact on disease manifestations and their ability to diminish joint damage [5]. With the development of biologics and Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors [2], these agents are being used by a rising number of patients including those with a mild disease. However, cost and safety issues remain key determinant [2, 5]. Personalized medicine is necessary to select special treatment strategies for certain clinical or molecular phenotypes of patients [6] and key factors of RA disease such as epidemiology, clinical presentations and treatment options should be presented.

In the milieu of the restricted information on the epidemiology and treatment patterns of RA across Egypt, the aim of the present study was to present the spectrum of RA in Egypt and compare it to other studies from around the world to provide broad-based characteristics to this particular population.

Patients and methods

Study population and design

This cross-sectional study included a large cohort of 10,364 adult RA patients (new and existing cases) fulfilling the American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism (ACR/EULAR) classification criteria [7] that were recruited from 26 specialized rheumatology departments and centers representing 22 major governorates across the country by members of the Egyptian College of Rheumatology (ECR) during the period from September 2018 till December 2021. Any patients with another rheumatic disease or below the age of 18 were excluded. The patients’ in the corresponding university-teaching hospitals provided informed consents to participate and the study was approved by the local ethics committee, in accordance to the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Measures and outcomes

Patients were subjected to full history taking and clinical examination. Juvenile-onset RA (JoRA) cases were considered for those who developed the disease before the age of 18 years. It is noteworthy that co-morbidities or manifestations relied on the records of the files. Presence of rheumatoid factor (RF) and/or anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) were determined. The use of medications to treat RA was described. Disease activity score (DAS28) [8] and health assessment questionnaire (HAQ) [9] were assessed.

Statistical analysis

Data were collected on a standardized data sheet and stored in an electronic database. Data missing completely at random (MCAR) as for the RF, anti-CCP and anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) positivity was handled by running a complete-case analysis (CCA), where all persons with missing values were excluded from the analysis of this test and imputation was not used. Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25 was used. Variables were presented as frequencies and percentages or mean and standard deviation. A comparison was done using Chi-square test, Mann Whitney U tests or analysis of variance (ANOVA). P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The study included 10,364 RA patients recruited from 22 governorates across Egypt. Their mean age was 44.8 ± 11.7 years. They were 8750 females and 1614 males (F:M 5.4:1). Characteristics of the patients and gender differences are presented in Table 1. 209 (2%) were Jo-RA. Steroids were received by 71.3% of the patients. DMARDs were received in the following descending frequency: methotrexate (MTX) (78%), hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) (73.6%), leflunomide (LFN) (54.8%), sulfasalazine (SAZ)(37.2%), cyclophosphamide (CYC) (2.4%), azathioprine (AZA)(2%), cyclosporine A (CSA)(0.5%) and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF)(0.46%). Steroids and DMARDs received were comparable between genders except for HCQ (male: 77.6% vs females 73%; p = 0.002). Biologic therapy was received by 11.6% with a significantly higher frequency by males vs females (15.7% vs 10.9%, p = 0.001). Biologic therapies received were etanercept (30.4%), adalimumab (18.4%), golimumab (14%), rituximab (7.9%), infliximab (3.3%), tofacitinib (1.6%), certolizumab (1%), upadacitinib (0.8%), baricitinib (0.39%), abatacept (0.39%) and undefined (17.8%). Patients also received low dose aspirin (4.6%), colchicine (1.3%) and oral anticoagulants (1.1%).

Certain variables according to the geo-location are presented in Table 2 and graphically presented in Figs. 1 and 2. The age at onset, gender distribution, disease activity, RF and anti-CCP positivity were significantly varied. The least age at onset, F:M, RF and anti-CCP positivity were present in Upper Egypt, while the highest DAS28 was reported in Canal cities and Sinai. The HAQ was significantly increased in Upper Egypt with the least disability in Canal cities and Sinai. Biological therapy intake was higher in Lower Egypt (46.3%), followed by the Capital (33.1%), Upper Egypt (20.3%) and the Canal cities and Sinai (0.2%) (p < 0.0001).

The age at onset, gender distribution, disease activity, rheumatoid factor and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide positivity as well as the main medications received by rheumatoid arthritis patients from the four main regions across Egypt. Lower Egypt (North coast and Delta); ALX: Alexandria, BH: Beheira, KS: Kafr El Sheikh, DM: Damietta, GB: Gharbia, DK: Dakahlia, SK: Sharkia, MNF: Menoufiya, KB: Kalyoubia. Canal cities and Sinai; PS: Port-Said, IS: Ismailia, SZ: Suez. Upper Egypt; FM: Fayoum, BS: Beni-Suef, MN: Minia, AST: Assuit, SO: Sohag, QN: Qena, LX: Luxor, ASW: Aswan. HCQ: hydroxychloroquine, MTX: methotrexate, LFN: leflunomide

Discussion

This cross-sectional study presented the socio-demographic, clinical, and therapeutic profile of 10,364 RA patients recruited across Egypt. In the present work the mean age at onset of RA patients in Egypt was 38 years which was significantly lower in females. The F:M was 5.4:1. The age at onset, gender distribution and disease characteristics of RA patients in countries from different continents were compared to the current study (Table 3). Interestingly, the age at onset was lower than that in other countries and nations [10,11,12,13,14,15] while it was comparable with that from Arab countries [16] and Turkey [17]. A potential explanation could be related to the lower average age of the populations in the Middle Eastern countries [18]. However, genetic and environmental factors cannot be excluded. The higher F:M was comparable to large registries from Latin America [13, 19, 20] thus raising the subject about an increasing shift in the ratio. Once more, the BMI in the RA patients of the current study were similar to that reported from Turkey [17]. RA, the most common inflammatory rheumatic disease, is no exception, with a F:M > 4 before 50 years old and < 2 after the age of 60 [21]. Furthermore, with the increasing incidence of spondyloarthritis (SpA) worldwide, it could have been that more male patients were misdiagnosed as having RA.

The misdiagnosis of SpA as RA leads to a delayed SpA diagnosis and inadequate therapeutic outcomes. Typical SpA-related clinical manifestations were present in RA patients. The advancements and accessibility of imaging modalities pave way for a more precise classification [12]. In this work, associated bronchial asthma and thyroid dysfunction, a family history of RA, Sjögren's syndrome, fibromyalgia syndrome and disease activity were significantly increased in females. It is notable that a lower frequency of females was receiving biologic therapy. On the contrary, males were significantly more smoking, had more renal manifestations, higher serum uric acid, more frequent positivity of RF and anti-CCP. Regarding the various clinical manifestations reported in this work, they were further compared to those from other countries.

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is a well-known potentially life-threatening complication in RA [22]. The enduring appraisal of the complex relationships between smoking, COPD, and other factors in RA-associated ILD is important [23]. In this work, the reported frequency of smoking in RA patients was lower (8.2%) than that from other studies from the UK (21.8%) [10], European Union (EU) and Canada (17.6%)[11] as well as Turkey (16.8%) [17].

In this work, neurological manifestations were reported at a low frequency. The frequencies of depression and anxiety were doubled in early RA than in long-standing disease. RA patients with short disease duration and functional limitation were more likely to suffer from depression and anxiety [24].

In this study, the reported frequency of cardiovascular manifestations was low. However, there is a considerable rise in mortality and morbidity in RA due to cardiovascular disease (CVD). The augmented risk for heart disease is related to disease activity and chronic inflammation with traditional risk factors and RA-related characteristics playing a central role [25]. RA patients had higher rates of obesity than the general population and this was strongly associated with physical dysfunction [26]. The BMI in this work was higher than that reported from other nations such as the UK [10] and EU [11]. Compared to osteoarthritis (OA), RA patients were significantly more frequently diabetic and smokers but had lower prevalence of obesity and dyslipidemia [27]. The frequency of metabolic syndrome in RA patients is doubled and raises the risks of stroke and heart disease [28]. The frequency of diabetes mellitus in this work was similar to the USA [12] and Latin American [19] registries, CVD was comparable to the USA CORRONA study [12] and chest involvement was in line to the Korean registry (KORRONA)[29].

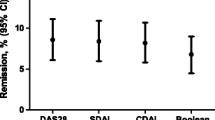

In this work, the RF was positive in 73.7% while the anti-CCP was positive in 66.7%. The frequency of RF was comparable to that from a large Colombian study on 68,247 cases [13] and to the CORONNA study from USA [12]. It was lower than Asian studies from Korea (86.8%)[29] and China (84.7%)[14]. Moreover, the frequency of anti-CCP positivity was lower than that reported in a Korean work (83.9%)[29] but higher than the registries from Colombia (24%)[13] and from the EU (32.7%)[11]. Anti-CCP and RF combined detection improves the diagnostic efficiency of RA, providing a potential strategy for early clinical screening [30]. The frequency of remission is three times higher in sero-negative patients with RA. However, the rate of remission does not depend on the serological status as almost two thirds of patients achieve remission in the first 6 months of DMARDs therapy. Anti-CCP and RF titers at the onset of the disease do not influence remission [31].

There was moderate disability in the present cases as measured by the HAQ. The functional capacity (physical and psychosocial) is a central treatment aspect to consider when the RA therapeutic strategy is personalized [32]. The average HAQ score reported in a population-based study was 0.49, and in RA was 1.2 [9]. The disease activity score in the present work was similar to that reported from the EU [11], higher than that from Turkey [17] and the USA [12] while it was lower than that from the UK [10] and China [14].

The medications received by the patients of the current study were diverse. In this study, more males were receiving HCQ and biologic therapy and with a lower disease activity. In early RA, targets can be achieved when the baseline level of diseases activity is low, with male gender and shorter disease duration [33]. In this work, MTX was received by 77.9%. Using MTX before initiating biologic therapy may contribute to a cost-effective RA care [34]. Variables related to MTX failure such as female gender, higher BMI, smoking, higher disease activity and diabetes can aid in predicting the disease process and outcome of treatment [35]. 54.8% of cases received leflunomide while 37.1% received sulfasalazine. Leflunomide is comparable to sulfasalazine in MTX-failed RA patients with similar safety profile [36]. 11.6% of the current patients were on biologics while in Korea a 6 times fold usage was reported [37].

Across the country there was a significant difference in the age at onset, gender distribution, disease activity, RF and anti-CCP positivity. A potential converse causal link between educational accomplishment and the risk of RA has been noticed [38].

National Registries are essential to direct current practice. RA registries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region are rarely presented [39]. On comparing the findings to countries from other continents, variations were easily noted.

In a study from Morocco on 225 RA cases, the age of onset (44 years), F:M (7.1:1), DAS28 (5.2 ± 1), RF positivity (90.5%), anti-CCP positivity (88.8%) were higher than the current findings however, those patients were all receiving biologic therapy [40].

In a study on 300 RA patients from Palestine, treatment with biologic therapy, younger age, having work, higher income, absence of morning stiffness and absence of co-morbidities were significantly associated with better quality of life and less disability [41]. In the work from a tertiary care hospital in KSA on 288 RA patients, the majority (88%) were females with a F:M 7.3:1. In agreement to this work, hypertension was the most common co-morbidity followed by diabetes and almost all of their patients had high disease activity at presentation time [42]. Compared to patients in Western countries, South Korean patients with RA, even those with better physical function, seem to have a lower quality of life [43]. In a study conducted by the Korean College of Rheumatology (KCR) on 2422 patients with a F:M 6.8:1, 19.4% were overweight and 16.1% obese, 13.6% smoked, 11.6% had dyslipidemia, 28% were hypertensive and 4.5% were diabetic. RF and anti-CCP were positive in 82.6% and 86.9%, respectively. The mean DAS28 was 4.7 ± 1.6, 79.9% were receiving steroids, 93.2% MTX, 68.8% HCQ and 46.3% LFN while 61.7% were on biologics [37].

In a large RA registry in the UK, of 27,607 patients, 70.6% were female (F:M 2.4:1) and their mean BMI was 27.3 [44]. In a study from 11 registries from 9 European countries: France, Sweden, Czech, UK, Denmark, Italy, Germany and Portugal on 130,315 RA patients; for biologic naive patients the age at onset was 56.4 years and F:M 2.6:1 and for those who received anti-TNF the age at onset was 46.5 years and F:M was 3:1 [45].

In a large nationwide US study, the F:M was 2.4:1. Obesity was present in 15.1%, diabetes in 20.4% and dyslipidemia in 48% [46].

Although this is currently the largest data of RA patients from across Egypt, there is a desperate need for effective and applicable national management strategies and guidelines. It seems that still across the country the diagnostic tests are not strictly considered for all patients. In spite that the medications received are mostly alike among the major cities, there is a disperse intake of biologic therapy being higher along a North to South gradient.

In conclusion, the spectrum of RA phenotype in Egypt is variable across the country with an increasing shift in the F:M ratio. The age at onset was lower than in other countries.

Data availability

Data are available upon request.

References

Chauhan K, Jandu JS, Goyal A, Bansal P, Al-Dhahir MA (2021) Rheumatoid arthritis. StatPearls [Internet]. Stat Pearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL)

Kondo N, Kuroda T, Kobayashi D (2021) Cytokine networks in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Mol Sci 22(20):10922

Sokolova MV, Schett G, Steffen U (2022) Autoantibodies in rheumatoid arthritis: historical background and novel findings. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 63(2):138–151

Salaffi F, Di Carlo M, Farah S, Marotto D, Atzeni F, Sarzi-Puttini P (2021) Rheumatoid arthritis disease activity assessment in routine care: performance of the most widely used composite disease activity indices and patient-reported outcome measures. Acta Biomed 92(4):e2021238

Curtis JR, Jain A, Askling J, Bridges SL Jr, Carmona L, Dixon W et al (2010) A comparison of patient characteristics and outcomes in selected European and U.S. rheumatoid arthritis registries. Semin Arthritis Rheum 40(1):2-14.e1

Heutz J, de Jong PHP (2021) Possibilities for personalised medicine in rheumatoid arthritis: hype or hope. RMD Open 7(3):e001653

Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, Funovits J, Felson DT, Bingham CO 3rd et al (2010) 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American college of rheumatology/ European league against rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum 62(9):2569–2581

Prevoo ML, van’t Hof MA, Kuper HH, van Leeuwen MA, van de Putte LB, van Riel PL (1995) Modified disease activity scores that include twenty-eight-joint counts. Development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 38(1):44–48

Bruce B, Fries JF (2003) The Stanford health assessment questionnaire: dimensions and practical applications. Health Qual Life Outcomes 1:20

Hamann PDH, Pauling JD, McHugh N, Shaddick G, Hyrich K, BSRBR-RA Contributors Group (2019) Predictors, demographics and frequency of sustained remission and low disease activity in anti-tumour necrosis factor-treated rheumatoid arthritis patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 58(12):2162–2169

Courvoisier DS, Alpizar-Rodriguez D, Gottenberg JE, Hernandez MV, Iannone F, Lie E et al (2016) Rheumatoid arthritis patients after initiation of a new biologic agent: trajectories of disease activity in a large multinational cohort study. EBioMedicine 11:302–306

Mease PJ, Bhutani MK, Hass S, Yi E, Hur P, Kim N (2022) Comparison of clinical manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis vs. spondyloarthritis: a systematic literature review. Rheumatol Ther 9(2):331–378

Santos-Moreno P, Castillo P, Villareal L, Pineda C, Sandoval H, Valencia O (2020) Clinical outcomes of patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated in a disease management program: real-world results. Open Access Rheumatol 12:249–256

Song X, Wang YH, Li MT, Duan XW, Li HB, Zeng XF, Co-authors of CREDIT (2021) Chinese registry of rheumatoid arthritis: IV. Correlation and consistency of rheumatoid arthritis disease activity indices in China. Chin Med J (Engl) 134(12):1465–1470

** S, Li M, Fang Y, Li Q, Liu J, CREDIT Co-authors (2017) Chinese registry of rheumatoid arthritis (CREDIT): II. Prevalence and risk factors of major comorbidities in Chinese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 19(1):251

Dargham SR, Zahirovic S, Hammoudeh M, Al Emadi S, Masri BK, Halabi H et al (2018) Epidemiology and treatment patterns of rheumatoid arthritis in a large cohort of Arab patients. PLoS ONE 13(12):e0208240

Ayhan FF, Ataman Ş, Rezvani A, Paker N, Taştekin N, Kaya T et al (2016) Obesity associated with active, but preserved joints in rheumatoid arthritis: results from our national registry. Arch Rheumatol 31(3):272–280

Youth UNPo (2011) Regional overview: youth in the Arab region

Ranza R, de la Vega MC, Laurindo IMM, Gómez MG, Titton DC, Kakehasi AM et al (2019) Changing rate of serious infections in biologic-exposed rheumatoid arthritis patients. Data from South American registries BIOBADABRASIL and BIOBADASAR. Clin Rheumatol 38(8):2129–2139

Castillo-Cañón JC, Trujillo-Cáceres SJ, Bautista-Molano W, Valbuena-García AM, Fernández-Ávila DG, Acuña-Merchán L (2021) Rheumatoid arthritis in Colombia: a clinical profile and prevalence from a national registry. Clin Rheumatol 40(9):3565–3573

Alpízar-Rodríguez D, Pluchino N, Canny G, Gabay C, Finckh A (2017) The role of female hormonal factors in the development of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 56(8):1254–1263

Qiu M, Jiang J, Nian X, Wang Y, Yu P, Song J et al (2021) Factors associated with mortality in rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Res 22(1):264

Zheng B, de Soares MC, Machado M, Pineau CA, Curtis JR, Vinet E, Bernatsky S (2022) Association between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, smoking, and interstitial lung disease onset in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 40(7):1280–1284

Geng Y, Gao T, Zhang X, Wang Y, Zhang Z (2022) The association between disease duration and mood disorders in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Clin Rheumatol 41(3):661–668

Rezuș E, Macovei LA, Burlui AM, Cardoneanu A, Rezuș C (2021) Ischemic heart disease and rheumatoid arthritis-two conditions, the same background. Life (Basel) 11(10):1042

Baker JF, Giles JT, Weber D, George MD, Leonard MB, Zemel BS et al (2021) Sarcopenic obesity in rheumatoid arthritis: prevalence and impact on physical functioning. Rheumatology (Oxford). https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keab710

Cacciapaglia F, Spinelli FR, Piga M, Erre GL, Sakellariou G, Manfredi A et al (2022) Estimated 10-year cardiovascular risk in a large Italian cohort of rheumatoid arthritis patients: data from the cardiovascular obesity and rheumatic disease (CORDIS) study group. Eur J Intern Med 96:60–65

Hee JY, Protani MM, Koh ET, Leong KP, Seng TT, Hospital Rheumatoid Arthritis Study Group (2022) Metabolic syndrome and its effect on the outcomes of rheumatoid arthritis in a multi-ethnic cohort in Singapore. Clin Rheumatol 41(3):649–660

Sung YK, Cho SK, Choi CB, Park SY, Shim J, Ahn JK et al (2012) Korean observational study network for arthritis (KORONA): establishment of a prospective multicenter cohort for rheumatoid arthritis in South Korea. Semin Arthritis Rheum 41(6):745–751

Yang X, Cai Y, Xue B, Zhang B (2021) Diagnostic value of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody combined with rheumatoid factor in rheumatoid arthritis in Asia: a meta-analysis. J Int Med Res 49(9):3000605211047714

Iaremenko O, Mykytenko G (2021) Achievement of clinical remission in patients with rheumatoid arthritis depending on the ACCP-and RF-serological status. Georgian Med News 318:99–104

Bywall KS, Esbensen BA, Lason M, Heidenvall M, Erlandsson I, Johansson JV (2022) Functional capacity vs side effects: treatment attributes to consider when individualising treatment for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol 41(3):695–704

Capelusnik D, Aletaha D (2022) Baseline predictors of different types of treatment success in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 81(2):153–158

Pardey N, Zeidler J, Nellenschulte TF, Stahmeyer JT, Hoeper K, Witte T (2021) Methotrexate treatment before use of biologics in rheumatoid arthritis: analysis of guideline compliance. Z Rheumatol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00393-021-01086-0

Siddiqui A, Totonchian A, Ali JB, Ahmad I, Kumar J, Shiwlani S et al (2021) Risk factors associated with non-respondence to methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Cureus 13(9):e18112

Belani PJ, Kavadichanda CG, Negi VS (2022) Comparison between leflunomide and sulfasalazine based triple therapy in methotrexate refractory rheumatoid arthritis: an open-label, non-inferiority randomized controlled trial. Rheumatol Int 42(5):771–782

Kim SK, Kwak SG, Choe JY (2020) Association between biologic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs and incident hypertension in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from prospective nationwide KOBIO registry. Medicine (Baltimore) 99(9):e19415

Huang G, Cai J, Li W, Zhong Y, Liao W, Wu P (2021) Causal relationship between educational attainment and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis: a Mendelian randomization study. BMC Rheumatol 5(1):47

Almoallim H, Hassan R, Cheikh M, Faruqui H, Alquraa R, Eissa A et al (2020) Rheumatoid arthritis Saudi database (RASD): disease characteristics and remission rates in a tertiary care center. Open Access Rheumatol 12:139–145

Eddaoudi M, Rostom S, Hmamouchi I, Binoune IE, Amine B, Abouqal R et al (2021) The first biological choice in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: data from the Moroccan register of biotherapies. Pan Afr Med J 38:183

Al-Jabi SW, Seleit DI, Badran A, Koni A, Zyoud SH (2021) Impact of socio-demographic and clinical characteristics on functional disability and health-related quality of life in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a cross-sectional study from Palestine. Health Qual Life Outcomes 19(1):241

AlOmair M, AlMalki H, AlShamrani N, Habtar G, AlAsmari M, Mobasher W et al (2021) Patterns of response to different treatment strategies in seropositive rheumatoid arthritis patients in a tertiary hospital in south-western Saudi Arabia: a retrospective study. Open Access Rheumatol 13:239–246

Suh CH, Lee K, Kim JW, Boo S (2022) Factors affecting quality of life in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in South Korea: a cross-sectional study. Clin Rheumatol 41(2):367–375

Hawley S, Edwards CJ, Arden NK, Delmestri A, Cooper C, Judge A et al (2020) Descriptive epidemiology of hip and knee replacement in rheumatoid arthritis: an analysis of UK electronic medical records. Semin Arthritis Rheum 50(2):237–244

Mercer LK, Askling J, Raaschou P, Dixon WG, Dreyer L, Hetland ML et al (2017) Risk of invasive melanoma in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with biologics: results from a collaborative project of 11 European biologic registers. Ann Rheum Dis 76(2):386–391

Peterson MN, Dykhoff HJ, Crowson CS, Davis JM 3rd, Sangaralingham LR, Myasoedova E (2021) Risk of rheumatoid arthritis diagnosis in statin users in a large nationwide US study. Arthritis Res Ther 23(1):244

Acknowledgements

Collaborators of the Egyptian College of Rheumatology: Gehad Elsehrawy, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1447-0543, Rheumatology Department, Faculty of Medicine, Suez-Canal University, Ismailia, Egypt. Soha Senara, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7495-8535, Rheumatology Department, Faculty of Medicine, Fayoum University, Fayoum, Egypt. Safaa Sayed, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4571-6638, Rheumatology Department, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt. Saad M Elzokm, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0623-6132. Rheumatology Department, Faculty of Medicine, Al-Azhar University, Damiette, Egypt. Emad El-Shebini, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9607-747X, Internal Medicine Department, Rheumatology Unit, Menoufia University, Menoufia, Egypt. Dina H El-Hammady, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5962-8255, Rheumatology Department, Faculty of Medicine, Helwan University, Cairo, Egypt. Ahmed Y Ismail, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8161-4666, Internal Medicine Department, Rheumatology Unit, Faculty of Medicine, Beni-Suef University, Beni-Suef, Egypt. Wael Abdel Mohsen, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6568-9847, Rheumatology Department, Faculty of Medicine, South Valley University, Qena, Egypt. Reem H Mohammed, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4994-7687, Rheumatology Department, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt. Hatem H El-Eishi, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6365-8024, Rheumatology Department, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt. Othman Hammam, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5195-5136, Assiut University Hospitals, Assiut University, Assiut Egypt.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

All co-authors contributed in line with the ICMJE 4 authorship criteria and take full responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of all aspects of the work. All co-authors take full responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gheita, T.A., Raafat, H.A., El-Bakry, S.A. et al. Rheumatoid arthritis study of the Egyptian College of Rheumatology (ECR): nationwide presentation and worldwide stance. Rheumatol Int 43, 667–676 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-022-05258-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-022-05258-2