Abstract

Pastoralism as a mode of production has had an important bearing on the livelihoods of many people in arid and semiarid environments. In the recent decades’ policies for land management in pastoral communities have changed from customary to statutory policies. This study analysed the dynamics of land management and their influence on the pastoral livelihood system at Kimana and Njoro villages in Kiteto district, northern Tanzania. Data for the study were collected from two focus groups, six key informants at the district level, and 296 households (equivalent to 10.1%) using household questionnaires, Findings show that whereas land is managed under customary and statutory laws, the emphasis is more on statutory laws. Statutory laws foster individualization of land ownership to some activities such as crop production, whereas communal lands are left for animal grazing only. Under statutory laws, individual land ownership is likely to be influenced by crop production, male-headed households, climate change, and resource use conflicts. However, statutory laws cannot guarantee sustainable resource management as the natural resources management institutions cannot dictate activities done in individual lands, as opposed to traditional systems. There is a need to harmonize traditional and modern forms of land management for increasing productivity and enhancing sustainable natural resources management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Pastoralism is a way of livestock production in which livestock keepers move their cattle, sheep and goats from place to place to take advantage of pasture and water which are available at different times during the year (Olengurumwa 2010).

Transhumance refers to seasonal migration between locations in which they have regular settlements with permanent houses See Leshan and Standslause (2013).

The Maasai compound.

1 USD = TZS 2236.80 in May, 2017

The Maasai homestead.

References

Andrachuk M, Armitage D (2015) Understanding social-ecological change and transformation through community perceptions of system identity. Ecol Soc 20(4):26. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-07759-200426.

Anebo LN (2016) Assessing the efficacy of African Boundary Delineation Law and Policy: the Case of Ethio – Eritrea Boundary Dispute Settlement.

Arsel Z (2017) Asking questions with reflexive focus: a tutorial on designing and conducting interviews. J Consumer Res https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucx096.

Basupi L, Quinn C, Dougill A (2017) Pastoralism and land tenure transformation in sub-saharan Africa: conflicting policies and priorities in Ngamiland, Botswana. Land 6(4):89. https://doi.org/10.3390/land6040089.

Boyce C, Neale P (2006) Conducting in-depth interviews: a guide for designing and conducting in-depth interviews. Evaluation 2(May):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730210154225.

Ekaya WN (2005) The shift from mobile pastoralism to sedentary crop-livestock farming in the drylands of eastern Africa: Some issues and challenges for research Afr Crop Sci Conf Proc 7(September):1513–1519.

Gaur MK, Squires VR (2017) Geographic extent and characteristics of the world’s arid zones and their peoples. In Climate Variability Impacts on Land Use and Livelihoods in Drylands (pp. 3–20). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56681-8_1.

Gibbs A (1997) Focus Groups. Social Research Update Issue 19, Guilford. http://sru.soc.surrey.ac.uk/SRU19.html.

Haile R (2017) Sedentarization and the creation of alternative livelihood among Saho Pastoralists in the Qohaito Plateau of Eritrea. Senri Ethnological Stud 95:293–318.

Kipkeu ML, Mwangi SW, Njogu J (2014) Community participation in wildlife conservation in Amboseli Ecosystem. Kenya IOSR J Environ Sci Ver II 8(4):2319–2399. https://www.iosrjournals.org.

Kiteto District Council (KDC) (2013) Kiteto District Council Strategic Plan 2013–2016. Kiteto.

Kratli S, Huelsebusch C, Brooks S, Kaufmann B (2013) Pastoralism: a critical asset for food security under global climate change. Anim Front 3(1):42–50.

Leshan MT, Standslause OEO (2013) Adaptation to the harsh conditions of the arid and semi-arid areas of Kenya: Is Pastoralism the best livelihood option? Asian J Appl Sci 2(4):22–29.

Lind JSW, Kohnstamm R, Caravani S, Eid M, Nightingale AM, Oringa DC (2016) Changes in the drylands of Eastern Africa: implications for resilience-strengthening efforts [Data set]. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies.

Lissu T (2000) Law, Social Justice & Global Development Policy and Legal Issues on Wildlife Management in Tanzania’s Pastoral Lands: The Case Study of the Ngorongoro Conservation Area. Law Social Justice and Global Development Jornal.

Morgan DL (1996) Focus groups. Annu Rev Sociol 22(1):129–152.

Mwamfupe D (2015) Persistence of farmer-herder conflicts in Tanzania. Int J Sci Res Publ 5(2):8.

National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) (2013) A 2012 Population and housing census; Population Distribution by Administrative Areas. National Bureau of Statistics.

Neely C, Bunning S (2008) Review of Evidence on Dryland Pastoral Systems and Climate Change: Implications and opportunities for mitigation and adaptation. FAO – NRL Working Paper. FAO: Rome.

Nelson F (2012) Natural conservationists? Evaluating the impact of pastoralist land use practices on Tanzania’s wildlife economy, 1–19.

Ogutu JO, Piepho HP, Said MY, Kifugo SC (2014) Herbivore dynamics and range contraction in Kajiado County Kenya: climate and land use changes, population pressures, Governance, policy and human-wildlife conflicts Open Ecol J 7(1):9–31.

Okello MM (2005) Land use changes and human-wildlife conflicts in the Amboseli area, Kenya. Hum Dimens Wildl 10(1):19–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871200590904851.

Olengurumwa OPK (2010) The bill of rights in Tanzania. The best or the worst? Paper presented during the workshop prepared by the Tanzania Teachers ‘Union.

Platteau JP (1996) The Evolutionary Theory of Land Rights as Applied to Sub-Saharan Africa: A Critical Assessment. Dev Change 27:29–86.

Redmond R, Curtis E (2009) Focus groups: principles and process. Nurse Researcher 16(3):57–69.

Reid RS, Nkedianye D, Said MY, Kaelo D, Neselle M, Makui O, Clark WC (2016) Evolution of models to support community and policy action with science: Balancing pastoral livelihoods and wildlife conservation in savannas of East Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci 113(17):4579–4584.

Rwegasira A (2012) Land as a Human Right. A History of Land Law and Practice in Tanzania. Dar es Salaam: Nkuki na Nyota Publisers Ltd.

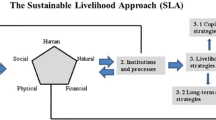

Scoones I (2009) Livelihoods perspectives and rural development. J Peasant Stud 36(1):171–196.

Secretariat of the Convention of the Biological Diversity CBD (2010) Pastoralism, Nature, Conservation and Development: A Good Practica Guide. Montreal.

Tesfay Y, Tafere K (2008) Indigenous Rangeland resources and Conflict Management by the North Afar Pastoral Groups in Ethiopia. Q J Int Agriculture 31:191–216.

Tynan CA, Drayton JL (1988) Conducting Focus Groups — a Guide for First‐Time Users. Mark Intell Plan 6(1):5–9.

United Republic of Tanzania (URT) (1997) The National Land Policy. Dar es Salaam: Ministry of Lands and Human Settlements Development.

URT (2006) National Livestock Policy. Dar es Salaam, Government Publishing House.

Yanda PZ, Mung’ong’o CG (2016) (Eds.) Pastoralism and Climate Change in East Africa. Dar es Salaam: Mkuki na Nyota Publishers Ltd.

Acknowledgements

The authors convey their heartfelt gratitude for significant contributions from those who, in one way or another, ensured an accomplishment of this task. Sincere thanks go to financial support from the project for Building Knowledge to Support Climate Change Adaptation for Pastoralist Communities in Eastern Africa Funded by Open Society Initiative for Eastern Africa (OSIEA). The project is implemented by the University of Dar es Salaam through the Centre for Climate Change Studies. We would like to acknowledge the contributions of all who were involved in data collection, including local government authorities for research clearance and logistical support. We send gratitude to Officers in Kiteto District Council, village leaders, and all respondents at large for their invaluable cooperation during field surveys. We recognize that the information they provided was instrumental in the successful completion of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yanda, P.Z., Mabhuye, E., Mwajombe, A. et al. Dynamics of Land Management and Implications on Pastoral Livelihoods in Northern Tanzania. Environmental Management 71, 29–39 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-021-01568-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-021-01568-6