Abstract

Redistribution is one of the most central functions of modern government. Against the backdrop of rising income inequality in many countries, policymakers and economists call for redistributive policies to address the rising inequality directly. Yet, there has been little systematic analysis of whether and how inequality influences redistribution and of the role of economic, political and institutional factors of redistribution. Our paper fills this important gap in the literature. To our knowledge, this is the first paper that systematically analyzes and presents evidence from a large panel of countries over 1967–2014 that high-income inequality is consistently associated with greater redistribution. Making it richer, evidence shows the role of economic factors such as trade openness, old age dependency, and financial development, and suggests that political institutions are important factors in understanding a cross-country variation in the size of redistribution. Extensive robustness checks confirm the results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Rising inequality has been attributed to a range of factors, including the globalization and liberalization of factor and product markets, skill-biased technological change, automation, weakening of labor bargaining power, superstar professionals and superstar firms, and declining top marginal income tax rates.

According to Jenkins et al. (2012), in the first two years following the Great Recession there was not much immediate change in disposable income distribution in many advanced economies because of government support via tax and benefits, with real income levels declining throughout the income distribution and large wealth losses for those at the top of the distribution. However, since then, widening inequality seems to have resumed in the recovery, as asset prices have risen, while wage growth has been stagnant (see Yellen 2014 and therein references). Some argue that post-crisis unconventional monetary policy has contributed to worsening inequality by inflating asset bubbles that tend to mostly benefit the wealthiest. See Bunn et al. (2018) on the recent UK experience.

Absolute redistribution (via taxes and social transfers) is measured by the difference between market income inequality and net income inequality, that is, absolute amount of the reduction in market income inequality due to taxes and transfers. Relative redistribution refers to the reduction in market income inequality as percent of initial market income inequality.

To put the order of magnitude in perspective, the median value of net income inequality (as measured by Gini coefficient on a 0–100 scale) is 29.15 and median size of redistribution (as measured by difference between market income inequality and net income inequality) is 15.77 in our LIS data for 47 countries in 1967–2014. On the other hand, the median value of 10-year change in the size of redistribution is 1.41.

Interestingly, Caminada et al. (2017) reach the similar conclusion by using a very different method (i.e., decomposition of the Gini coefficient of market income into net income Gini coefficient and contributions from 9 different benefits and income taxes and social contributions).

Related, Razin et al. (2004) develop a majority-voting model that predicts that tax rates on capital income could rise as the population ages, and find supporting evidence from a panel data for ten European Union countries in 1970–1996.

In a broad context, there have been debates on whether globalization would lead to a retrenchment of the welfare state by eroding the government’s capability to redistribute income and wealth, even when it makes the redistribution more desirable in more open economies, as multilateral trade liberalization and technological progress make borders less of a barrier to economic activity (e.g., relocation of firms to low-tax and low-cost countries). See Rodrik (1997), Garrett and Mitchell (2001) and Crepaz and Moser (2004) among others. More recently, globalization seems to have played an important role in driving up support for populist movements. See Rodrik (2021).

It takes a value of 1 if Democracy score from Polity IV is greater than 8 and 0 otherwise. Democracy score ranges between 0 (no democracy) and 10 (full democracy). Further details are provided in the text later.

Also, if we split the sample between democracies and non-democracies and run regression separately, we reach a similar conclusion.

For example, see Persson and Tabellini (2003) and Woo (2003) for empirical studies on fiscal policy outcomes of political systems; see Es**-Andersen (1991), Huber and Stephens (2001), and Jensen (2014) about the role of left-wing political parties as a driving force of social welfare expansion in advanced industrial democracies; see Hallerberg and von Hagen (1999), Woo (2003, 2009), Crepaz and Moser (2004), and König et al. (2011) about the role of institutionalized checks and balances in political decision makings; and see Alt and Lowry (1994) and Alesina and Rosenthal (2000) about policy outcomes of united versus divided governments.

It is because the distribution of political power is more equal than the distribution of income or wealth. To the extent that public decisions are made by majority rule, the decisive voter (i.e., median voter) will vote for higher redistributive spending which is accompanied with higher taxes because the benefit to the median voter from redistributive transfers outweighs the burden of taxation (i.e., the tax burden disproportionately falls on higher income voters).

Somewhat related to this, Acemoglu et al. (2015) finds that democracy is associated with an increase in tax revenue as a percent of GDP, but not significantly associated with lower income inequality. Their focus is on the direct effects of democratization per se on inequality and other variables such as tax revenue and secondary school enrollment.

The SWIID employs a missing-data algorithm that uses information from proximate years within the same countries, while taking the LIS as a benchmark. However, the increased coverage and comparability does not come without cost—for example, when the information from proximate years within the same countries is unavailable, the quality of imputation itself and how to account for multiply-imputed observations are the issues. This leads some (e.g., Jenkins 2014) to prefer to use the WIID with a dummy variable approach (that is, dummy variables indicating whether the data point is net income inequality or market income inequality, or it is per household or household adult equivalent, etc.) rather than the SWIID. However, for our purpose, this approach would not work.

For lack of the standard empirical model of redistribution, we consider a large empirical literature on the determinants of income inequality, which includes national income per capita, education, trade openness, and old age dependency as explanatory variables of cross-country variations in inequality (e.g., de Gregorio and Lee 2002; Barro 2008; Woo et al. 2017).

The time interval for each LIS Wave is not uniform. Historical Wave I (1967–1973) has a 7-year interval, and from Historical Wave II (1974–1978) through Wave V (1998–2002), each has a 5-year interval. Beginning with Wave VI (2003–2006), it is a 3-year interval.

The absolute measure of redistribution makes it easier to interpret the coefficients. On the other hand, the relative measures of redistribution tracked over time can be viewed as the “percentage change in percentage change” (Caminda et al. 2012).

This was performed given that redistribution and inequality are likely persistent over time. Note that the panel data has N = 47 (countries) and T = 11 (periods) where the periods are several years apart (3 or 5 or 7 years). The number of available data points on redistribution and inequality from the LIS tends to be fewer than 11 for most countries. For example, only Germany and the UK have 11 observations available; Australia (8 observations), Austria (6); Belgium (4); Brazil (4); China (1); Denmark (8); Egypt (1); France (7); Japan (1); Korea (4); South Africa (3); Spain (9); Switzerland (7); and the US (10). For practical purposes, this raises doubt about the power of augmented Dickey-Fuller test for a stationarity of redistribution and inequality. Nonetheless, for example, if we perform an augmented Dickey-Fuller test for Germany and the US, we can still reject the null hypothesis of a random walk (with drift) for redistribution at the conventional levels.

It refers to the tendency that as nations industrialize, the share of the public sector in the economy grows because of political pressure for social activities of the state, administrative and protective actions, and welfare functions. For example, Bojanic (2013) and Afonso and Alves (2017) provide evidence based on disaggregated expenditure data for Bolivia and 14 European countries, respectively.

The Kuznets curve implies that inequality exhibits an inverted U-curve as the economy develops: economic development (including shifts from agriculture to industry and services and adoption of new technologies) initially benefits a small segment of the population, causing inequality to rise. Subsequently, inequality declines as the majority of people find employment in the high-income sector. However, the existing evidence for the Kuznets curve is mixed (see Barro 2008 and references therein).

A similar argument can apply to terms-of-trade growth, including the ‘voracity effect’ in Tornell and Lane (1999) in which a windfall gain (e.g., oil boom) may perversely generate a more than proportionate increase in fiscal redistribution, when a country lacks legal, political, and institutional constraints on the government spending policy.

For economic variables such as income per capita, government size, old age dependency ratio, trade openness, and financial market depth, their initial values (i.e., measured at the beginning year of each period) are used in the regression. For political variables, their average values over the previous period are used to capture the slower yet long-lasting effects on redistribution of political institutions.

Intuitively, the within-transformation (i.e., demeaning) under FE may exacerbate the measurement error bias by decreasing the signal-to-noise ratio (Grilliches and Hausman 1987).

In an extensive evaluation of growth regressions in relation to macroeconomic policy variables, for example, Easterly (2005) argues that some of the large effects on growth of a policy variable in the earlier empirical studies are often caused by outliers that represent “extremely bad” policies.

It is essentially an iterated re-weighted least squares regression in which the outliers are dropped (if Cook’s distance is greater than 1) and the observations with large absolute residuals are down-weighted.

Importantly, the difference-in-Hansen tests of exogeneity of instrument subsets do not reject the null hypothesis that the instrument subsets for the level equations are orthogonal to the error (p value = 0.13), that is, the assumption that lagged differences of endogenous explanatory variables that are being used as instruments in levels is uncorrelated with the errors. This is the additional restriction that needs to be satisfied for the SGMM estimator.

The dynamic panel GMM can generate too many instruments, which may overfit endogenous variables and run a risk of a weak-instruments bias. However, a standard test of weak instruments in panel GMM regressions does not currently exist (Bazzi and Clemens 2013). See Stock et al. (2002) on why the weak instrument diagnostics for linear IV regression do not carry over to the more general setting of GMM. Given that, one recommendation when faced with a weak-instrument problem is to be parsimonious in the choice of instruments. Roodman (2009) and Kraay (2015) suggest restricting the number of lagged levels used in the instrument matrix or collapsing the instrument matrix or combining the two. We followed this recommendation and obtained the SGMM results for our paper by combining the “collapsed” instrument matrix with lag limits.

As an alternative variable of financial depth, we tried private credit extended by banks and other financial institutions (as a percent of GDP) and obtained similar results (not reported to save space).

A plausible idea is as follows. In a seminal paper, Galor and Zeira (1993) show that in the presence of credit markets’ imperfections and indivisibilities in investment in human capital, the initial distribution of wealth can perpetuate the initial inequality of wealth. It is because agents whose initial endowment is below a certain minimum needed to pay for education cannot accumulate human capital unless they have access to credit. Thus, to the extent that well-developed financial markets alleviate the budget constraint and provide the poor to access to credit, the poor can also accumulate human capital and earn higher income, thereby reducing their demand for income redistribution. However, access to credit may still remain unequitable despite the financial market development, which can then aggravate inequality and lead to a greater demand for redistribution, not less. Thus, it is fundamentally an empirical question.

In their original model of Meltzer and Richard (1981), the relative measure of redistribution can be viewed as a proxy for the linear income tax rate which they predict will rise as a result of greater market income inequality (as measured by the gap between average income and median voter’s income). The model assumes that taxes are levied on all private sector income using a linear tax rate and that all the proceeds from taxation are redistributed in an equal lump sum among the economic agents.

Put this in perspective, the mean value of market income inequality in the LIS data is 46.2; mean absolute redistribution is 14.4; and mean relative redistribution is 31. Thus, 0.45–0.47 percentage points of the average market income inequality are about 0.2 Gini points.

We also tried the 50th percentile as the threshold. The results do not change any appreciably.

The cutoff value of 8 for the dummy variable corresponds to the 39th percentile of available observations.

A caveat is that in the sample of non-democratic countries, the size and statistical significance of the coefficients of market income inequality tends to lessen.

They also find that in parliamentary regimes, spending (and particularly welfare spending) displays a more pronounced response than in presidential regimes to the common global events that led to the expansion of government spending from the 1960s to the mid-1980s.

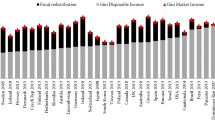

In the previous version, we presented the baseline regression results for the entire sample of 140 countries. They are qualitatively similar to the baseline results based on the LIS, especially with the coefficients of market income inequality being positive and all significant at 1–5% (the coefficients range from 0.210 to 0.245). The overall goodness of fit and statistical significance of other variables further weaken. Not surprisingly, this may reflect the fact that low-income develo** countries engage in much less fiscal redistribution because of their limited government budgets and effectiveness (recall Fig. 2).

References

Acemoglu D, Naidu S, Restrepo P, Robinson JA (2015) Democracy, redistribution, and inequality. In: Atkinson AB, Bourguignon F (eds) Handbook of income distribution, vol 2. North-Holland, Amsterdam, pp 1885–1966

Afonso A, Alves J (2017) Reconsidering Wagner’s law: evidence from the functions of the government. Appl Econ Lett 24(5):346–350

Alesina A, Rodrik D (1994) Distributive politics and economic growth. Q J Econ 109(2):465–490

Alesina A, Rosenthal H (2000) Polarized platforms and moderate policies with checks and balances. J Public Econ 75:1–20

Alt JE, Lowry RC (1994) Divided government, fiscal institutions, and budget deficits: evidence from the states. Am Polit Sci Rev 88(4):811–828

Alvaredo F, Atkinson AB, Piketty T, Saez E (2013) The top 1 percent in international and historical perspective. J Econ Perspect 27(3):3–20

Arellano M, Bover O (1995) Another look at the instrumental variables estimation of error-components models. J Econom 68:29–51

Atkinson AB, Brandolini A (2001) Promise and pitfalls in the use of secondary data-sets: income inequality in OECD countries as a case study. J Econ Lit 39(3):771–799

Babones SJ, Alvarez-Rivadulla MJ (2007) Standardized income inequality data for use in cross-national research. Sociol Inq 77(1):3–22

Barro R (2008) Inequality and growth revisited. Asian Development Bank Working Paper Series on Regional Economic Integration, No. 11, January

Bazzi S, Clemens M (2013) Blunt instruments: avoiding common pitfalls in identifying the causes of economic growth. Am Econ J Macroecon 5(2):152–186

Benabou R (1996) Inequality and growth. In Bernanke BS, Rotemberg JJ (eds) NBER macroeconomics annual 1996, vol 11, pp11–92

Berg A, Ostry JD, Tsangarides CG, Yakhshilikov Y (2018) Redistribution, inequality, and growth: new evidence. J Econ Growth 23(3):259–305

Blundell R, Bond S (1998) Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. J Econom 87(1):115–143

Bojanic AN (2013) Testing the validity of Wagner’s law in Bolivia: a cointegration and causality analysis with disaggregated data. Revista De Analisis Economico Econ Anal Rev 28(1):25–45

Boushey H (2019) Unbound: how inequality constricts our economy and what we can do about it. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Bunn P, Pugh A, Yeates C (2018) The distributional impact of monetary policy easing in the UK between 2008 and 2014. Bank of England, Staff Working Paper No. 720

Caminada K, Goudswaard K, Wang C (2012) Disentangling income inequality and the redistributive effect of taxes and transfers in 20 LIS countries over time. LIS Working Paper No. 581

Caminada K, Wang J, Goudswaard K, Wang C (2017) Income inequality and fiscal redistribution in 47 LIS-countries, 1967–2014. LIS Working Paper No. 724

Causa O, Hermansen M (2017) Income redistribution through taxes and transfers across OECD countries. OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1453

Crepaz MML, Moser AW (2004) Veto points, the impact of collective and competitive veto points on public expenditures in the global era. Comp Polit Stud 37(3):259–285

de Gregorio J, Lee J (2002) Education and income inequality: new evidence from cross-country data. Rev Income Wealth 48(3):395–416

de Mello LD, Tiongson ER (2006) Income inequality and redistributive government spending. Public Finance Rev 34(3):282–305

de Tocqueville A (1835) Democracy in America, Reprinted. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Deininger K, Squire L (1996) A new data set measuring income inequality. World Bank Econ Rev 10:565–591

Easterly W (2005) National policies and economic growth. In: Aghion P, Durlauf S (eds) Handbook of economic growth. North-Holland, Amsterdam

Easterly W (2007) Does inequality cause underdevelopment: insights from a new instrument. J Dev Econ 84(2):755–776

Eichengreen B (2020) The populist temptation. Oxford University Press, London

Epifani P, Gancia G (2009) Openness, government size and the terms of trade. Rev Econ Stud 76(2):629–668

Es**-Andersen G (1991) The three political economies of the welfare state. In: Kolberg JE (ed) The study of welfare state regimes. M. E. Sharpe, Armonk

Furceri D, Loungani P, Ostry JD, Pizzuto P (2021) Will COVID-19 have long-lasting effects on inequality? Evidence from past pandemics. IMF Working Paper 21/127

Galor O, Zeira J (1993) Income distribution and macroeconomics. Rev Econ Stud 60:35–52

Garrett G, Mitchell D (2001) Globalization, government spending and taxation in the OECD. Eur J Polit Res 39:145–177

Grilliches Z, Hausman J (1987) Errors in variables in panel data. J Econom 31(1):93–118

Hallerberg M, von Hagen J (1999) Electoral institutions, cabinet negotiations, and budget deficits in the European Union. In: Porterba JM, von Hagen J (eds) Fiscal institutions and fiscal performance. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Hauk W, Wacziarg R (2009) A Monte Carlo study of growth regressions. J Econ Growth 14(2):103–147

Huber E, Stephens JD (2001) Development and crisis of the welfare state: parties and policies in global markets. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

IMF (2014) Fiscal policy and income inequality. IMF Policy Paper, January 23, 2014

Jenkins SP (2014) World income inequality databases: an assessment of WIID and SWIID. London School of Economics, Working Paper

Jenkins SP, Brandolini A, Micklewright J, Nolan B (2012) The great recession and the distribution of household income. Oxford University Press

Jensen C (2014) The right and the welfare state. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Kakwani N (1986) Analyzing redistribution policies: a study using Australian data. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Kenworthy L, Pontusson J (2005) Rising inequality and the politics of redistribution in affluent countries. Perspect Polit 3:449–471

König T, Tsebelis G, Debus M (2011) Reform processes and policy change: veto players and decision-making in modern democracies. Springer, New York

Kraay A (2015) Weak instruments in growth regressions: implications for recent cross-country evidence on inequality and growth. World Bank Working Paper 7494

Luebker M (2014) Income inequality, redistribution, and poverty: contrasting rational choice and behavioral perspectives. Rev Income Wealth 60(1):133–154

Meltzer A, Richard S (1981) A rational theory of the size of government. J Polit Econ 89(5):914–927

Milanovic B (2000) The median-voter hypothesis, income inequality, and income redistribution: an empirical test with the required data. J Polit Econ 16:367–410

Mulligan CB, Gil R, Sala-i-Martin X (2004) Do democracies have different public policies than nondemocracies? J Econ Perspect 18(1):1–26

OECD (2015) Growth and income inequality: trends and policy implications. OECD Economics Department Policy Notes, No. 26 April 2015

Pastor L, Veronesi P (2020) Inequality aversion, populism, and the backlash against globalization. NBER, Working Paper No. 24900

Perotti R (1996) Growth, income distribution, and democracy: what the data say? J Econ Growth 1:149–187

Persson T, Tabellini G (1994) Is inequality harmful for growth? Am Econ Rev 84:600–621

Persson T, Tabellini G (2003) The economic effects of constitutions. MIT Press, Cambridge

Piketty T (2014) Capital in the 21st century. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Piketty T, Saez E, Zucman G (2018) Distributional national accounts: methods and estimates for the United States. Q J Econ 133(2):553–609

Razin A, Sadka E, Swagel P (2004) Capital income taxation under majority voting with aging population. Rev World Econ 140(3):476–495

Rodrik D (1997) Has the globalization gone too far? Institute for International Economics, Washington

Rodrik D (1998) Why do more open economies have bigger governments? J Polit Econ 106(5):997–1032

Rodrik D (2021) Why does globalization fuel populism? Economics, culture, and the rise of right-wing populism. Annu Rev Econ 13:133–170

Roodman D (2009) A note on the theme of too many instruments. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 71(1):135–158

Saez E, Zucman G (2016) Wealth inequality in the United States since 1913: evidence from capitalized income tax data. Q J Econ 131(2):519–578

Scervini F (2012) Empirics of the median voter: democracy, redistribution and the role of the middle class. J Econ Inequal 10:529–550

Shugart MS, Carey JM (1992) Presidents and assemblies: constitutional design and electoral dynamics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Stantcheva S (2022) Inequalities in the times of a pandemic. Econ Policy 37:5–41

Stiglitz J (2014) Inequality in America: a policy agenda for a stronger future. 2014 Moynihan Prize Lecture

Stiglitz J (2022) COVID has made global inequality much worse. Scientific American, March, 2022

Solt F (2016) The standardized world income inequality database. Soc Sci Q 97(5):1267–1281 (SWIID Version 6.2, March 2018)

Stock JH, Wright JH, Yogo M (2002) A survey of weak instruments and weak identification in generalized method of moments. J Bus Econ Stat 20(4):518–529

Tornell A, Lane P (1999) The voracity effect. Am Econ Rev 89(1):22–46

Woo J (2003) Economic, political, and institutional determinants of public deficits. J Public Econ 87(3–4):387–426

Woo J (2009) Why do more polarized countries run more procyclical fiscal policy? Rev Econ Stat 91(4):850–870

Woo J (2011) Growth, income distribution, and fiscal policy volatility. J Dev Econ 96(2):289–313

Woo J, Kumar M (2015) Public debt and growth. Economica 82(328):705–739

Woo J, Bova E, Kinda T, Zhang YS (2017) Distributional consequences of fiscal adjustments. IMF Econ Rev 65(2):273–307

Yellen J (2014) Perspectives on inequality and opportunity from the survey of consumer finances. Federal Reserve Board.

Funding

This study was financially supported by a research grant from the Kellstadt Graduate School of Business at DePaul University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that I have no conflict of interests with Bank of America Merrill Lynch (Hong Kong).

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This paper was partly written while I was Chief Korea Economist at Bank of America Merrill Lynch, Hong Kong. I would like to thank David Coady, John Berdell, Elva Bova, Animesh Goshal, Tidiane Kinda, Jimman Lee, Sebastien Mary, Marcos Poplawski-Rebeiro, Brian Phelan, Philippe Wingender, and participants in IMF and DePaul seminars for helpful discussions and comments. In particular, conversations with the then deputy director of Fiscal Affairs Department at the IMF, Sanjeev Gupta, rekindled my interest in the subject. I thank Editor-in-Chief Joakim Westerlund and two anonymous referees for their excellent comments and suggestions. Esmeralda Popo provided excellent research assistance. I gratefully acknowledge a research grant from the Kellstadt Graduate School of Business.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Country list

-

(1)

Luxembourg Income Study (LIS) data originally includes the following 47 countries. Among them, 21 advanced industrial democracies included in Columns 6–10 of Table 1 are with † mark.

Australia† | Finland† | Japan† | Slovak Rep |

Austria† | France† | Luxembourg† | Slovenia |

Belgium† | Georgia | Mexico | South Africa |

Brazil | Germany† | Netherlands† | South Korea |

Canada† | Greece† | Norway† | Spain† |

China | Guatemala | Panama | Sweden† |

Colombia | Hungary | Paraguay | Switzerland† |

Czech Republic | Iceland† | Peru | Taiwan |

Denmark† | India | Poland | United Kingdom† |

Dominican Rep | Ireland† | Romania | United States† |

Egypt | Israel | Russia | Uruguay |

Estonia | Italy† | Serbia |

-

(2)

59 OECD and emerging market economies included in the regression based on the SWIID data (Table 8): Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, China, Colombia, Czech Rep, Denmark, Egypt, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, India, Indonesia, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malaysia, Mexico, Morocco, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Pakistan, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Singapore, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Thailand, Turkey, Ukraine, United Kingdom, United States, and Venezuela.

Appendix 2: Description of data

2.1 Dependent variables

-

(1)

Absolute redistribution (as measured by difference between market income inequality and net income inequality), LIS data from Caminada et al. (2017) for Tables 1–2 and 4, 5, 6, 7.

-

(2)

Relative redistribution (as measured by difference between market income inequality and net income inequality divided by market income inequality), LIS data from Caminada et al. (2017) for Table 3.

-

(3)

Absolute redistribution (as measured by difference between market income inequality and net income inequality), SWIID data version 6.2 from Solt (2016) for Table 8.

2.2 Explanatory variables

-

(1)

Real GDP per capita (in log), PWT9.0 (2017)

-

(2)

Government size (percent of GDP), PWT9.0 (2017)

-

(3)

Aged-dependency ratio (ratio of population of age over 65 to working-age population), WDI (2018)

-

(4)

Trade openness (percent of GDP), WDI (2018)

-

(5)

Real GDP growth (in percent), PWT9.0 (2017)

-

(6)

Financial market depth (liquid liabilities as percent of GDP), Financial Structure Database (2018)

-

(7)

Private credit by banks and other financial institutions (percent of GDP), Financial Structure Database (2018)

-

(8)

Market income inequality, LIS data from Caminada et al. (2017) and SWIID (Solt 2016)

-

(9)

Democracy, Polity IV (2018)

-

(10)

Polity score, Polity IV (2018)

-

(11)

Constraints on executive decision-making, Polity IV (2018)

-

(12)

Political system (presidential, assembly-elected presidential, parliamentary), DPI (2017)

-

(13)

Economic policy orientation of the Chief Executive’s party (left, center, right), DPI (2017)

-

(14)

All house (indicator of whether party of executive control all relevant houses), DPI (2017)

-

(15)

Checks and balances (number of veto players), DPI (2017).

Appendix 3: Summary statistics

Variable | Obs | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Entire sample | |||||

LIS data | |||||

Market income inequality | 268 | 46.15 | 6.11 | 27.19 | 66.49 |

Size of redistribution (absolute) | 268 | 14.35 | 6.89 | 0.01 | 29.94 |

Size of redistribution (relative) | 268 | 30.95 | 14.23 | 0.02 | 54.80 |

SWIID data | |||||

Market income inequality | 696 | 46.22 | 6.59 | 28.00 | 68.50 |

Size of redistribution (absolute) | 696 | 8.51 | 6.89 | 0.10 | 31.60 |

Explanatory variables | |||||

Real GDP per capita (log) | 268 | 10.05 | 0.59 | 7.75 | 11.42 |

Trade openness | 267 | 76.83 | 46.02 | 12.45 | 325.83 |

Old age dependency | 268 | 19.10 | 5.79 | 6.28 | 32.68 |

Government size | 268 | 18.04 | 5.84 | 6.78 | 44.46 |

Financial market depth | 255 | 69.72 | 50.35 | 15.89 | 372.47 |

Private credit by financial institutions | 257 | 74.05 | 43.69 | 4.25 | 217.95 |

Economic growth | 266 | 3.74 | 2.62 | − 4.30 | 11.42 |

Democracy (0–10(full ldemocracy)) | 264 | 9.03 | 1.94 | 0.00 | 10.00 |

Dummy for democracy (1 if democracy > 8) | 264 | 0.79 | 0.41 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

Polity2 (= democracy—autocracy) | 264 | 8.77 | 2.82 | − 7.20 | 10.00 |

Policy-orientation (right(1), center(2), left(3)) | 251 | 1.80 | 0.93 | 0.00 | 3.00 |

Checks | 258 | 4.13 | 1.33 | 1.00 | 11.80 |

All houses controlled by party of executive | 253 | 0.24 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

Political system (presidential(1), assembly-elected presidential(2), parliarmentary(3)) | 258 | 1.41 | 0.87 | 0.00 | 2.00 |

Appendix 4: Panel regressions—alternative regression specification; dependent variable: first difference in size of redistribution

Explanatory variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

BE | Pooled OLS | RR | FE | SGMM | BE | Pooled OLS | RR | FE | SGMM | |

Real GDP per capita (log) | − 0.591* | − 0.728*** | − 0.543*** | − 1.588 | − 1.402*** | − 1.047* | − 1.150*** | − 0.889*** | − 2.475 | − 1.463 |

(− 1.90) | (− 3.40) | (− 2.99) | (− 1.30) | (− 2.75) | (− 1.87) | (− 3.22) | (− 2.84) | (− 1.60) | (− 1.64) | |

First difference in market income inequality | 0.291*** | 0.702*** | 0.583*** | 0.741*** | 0.775*** | 0.286*** | 0.712*** | 0.585*** | 0.760*** | 0.831*** |

(2.97) | (9.31) | (16.21) | (15.20) | (9.16) | (2.78) | (8.94) | (15.74) | (14.91) | (11.44) | |

Trade openness | 0.001 | − 0.002 | − 0.000 | − 0.001 | − 0.014** | |||||

(0.20) | (− 0.75) | (− 0.09) | (− 0.13) | (− 2.09) | ||||||

Old age dependency | 0.007 | 0.020 | 0.030 | − 0.112 | − 0.160** | |||||

(0.20) | (0.93) | (1.25) | (− 1.13) | (− 2.21) | ||||||

Government size | − 0.034 | − 0.022 | − 0.007 | 0.036 | 0.045 | |||||

(− 1.01) | (− 0.85) | (− 0.34) | (0.41) | (0.30) | ||||||

Financial market depth | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.008 | 0.012* | |||||

(0.61) | (1.38) | (0.52) | (0.78) | (1.74) | ||||||

Economic growth | − 0.107 | 0.090 | 0.073 | 0.134* | 0.089 | |||||

(− 0.99) | (1.41) | (1.58) | (1.67) | (0.64) | ||||||

Political system | 0.035 | 0.214 | 0.185 | 0.364 | 1.237 | |||||

(0.12) | (1.41) | (1.12) | (0.42) | (1.60) | ||||||

Arellano-Bond AR(2) test p valuea | 0.178 | 0.133 | ||||||||

Hansen J-statistics (p value)b | 0.116 | 0.355 | ||||||||

No. of obs | 214 | 214 | 214 | 214 | 214 | 202 | 202 | 202 | 202 | 202 |

No. of countries | 41 | 41 | 41 | 41 | 41 | 39 | 39 | 39 | 39 | 39 |

R 2 | 0.190 | 0.607 | 0.623 | 0.640 | 0.243 | 0.637 | 0.641 | 0.670 | ||

Time-fixed effects | N/A | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Appendix 5: Panel regressions—market income inequality, redistribution, and democracy; dependent variable: size of redistribution

Explanatory variables | Democracies | Non-democracies | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | |

BE | Pooled OLS | RR | FE | SGMM | BE | Pooled OLS | RR | FE | SGMM | |

Real GDP per capita (log) | 6.259*** | 5.207*** | 5.439*** | 2.611* | 11.020** | 2.204 | 2.522 | 1.936*** | 7.037*** | 7.964 |

(3.02) | (7.04) | (10.08) | (1.90) | (2.63) | (1.26) | (1.72) | (6.62) | (3.45) | (0.93) | |

Market income inequality | 0.374*** | 0.371*** | 0.412*** | 0.713*** | 0.782*** | 0.303* | 0.359*** | 0.270*** | − 0.020 | 0.243 |

(2.89) | (3.83) | (8.84) | (13.07) | (4.33) | (1.94) | (3.01) | (9.65) | (− 0.19) | (0.74) | |

Trade openness | 0.032 | 0.032*** | 0.028*** | − 0.010 | 0.041** | − 0.055 | − 0.011 | − 0.047*** | 0.038 | 0.037 |

(1.50) | (3.67) | (4.69) | (− 1.17) | (2.27) | (− 1.08) | (− 0.31) | (− 5.46) | (1.12) | (0.48) | |

Old age dependency | 0.502*** | 0.314*** | 0.247*** | − 0.028 | 0.093 | 0.697** | 0.645*** | 0.502*** | − 0.327 | 1.078 |

(3.39) | (2.84) | (4.72) | (− 0.34) | (0.31) | (2.70) | (5.85) | (11.03) | (− 0.76) | (1.07) | |

Government size | 0.196 | 0.359*** | 0.459*** | 0.061 | 0.492* | 0.179 | 0.192* | 0.443*** | 0.275** | 0.235 |

(1.57) | (3.14) | (10.48) | (0.67) | (1.80) | (1.01) | (1.91) | (12.54) | (2.68) | (0.80) | |

Financial market depth | − 0.050*** | − 0.032*** | − 0.029*** | 0.000 | − 0.034* | 0.008 | 0.026 | 0.062*** | − 0.016 | 0.009 |

(− 3.28) | (− 4.12) | (− 5.28) | (0.05) | (− 1.78) | (0.22) | (1.16) | (8.39) | (− 0.42) | (0.08) | |

Economic growth | 0.546 | − 0.163 | − 0.097 | − 0.037 | − 0.141 | − 0.638 | 0.081 | − 0.275*** | − 0.040 | 0.087 |

(0.75) | (− 1.32) | (− 0.97) | (− 0.54) | (− 0.55) | (− 1.24) | (0.89) | (− 5.39) | (− 0.59) | (0.36) | |

Political system | 2.430** | 1.177 | 1.282*** | 14.198** | − 1.513 | 1.205 | 0.635 | − 1.151*** | − 2.109** | − 2.878 |

(2.63) | (1.53) | (4.05) | (2.38) | (− 0.33) | (0.66) | (0.44) | (− 3.56) | (− 2.86) | (− 0.58) | |

Arellano-Bond AR(2) test p value1 | 0.578 | 0.767 | ||||||||

Hansen J-statistics (p value)2 | 0.592 | 1.000 | ||||||||

No. of obs | 195 | 196 | 197 | 198 | 199 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 47 |

No. of countries | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

R 2 | 0.838 | 0.796 | 0.823 | 0.756 | 0.901 | 0.904 | 0.989 | 0.951 | ||

Time-fixed effects | N/A | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Woo, J. The long-run determinants of redistribution: evidence from a panel of 47 countries in 1967–2014. Empir Econ 64, 1811–1860 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-022-02296-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-022-02296-4