Abstract

Iron is extremely insoluble in oxic seawater. The lack of a large aqueous reservoir means that sediments rich in authigenic iron are rare in the modern ocean. In the Middle Jurassic, however, condensed iron-rich sedimentary rocks are widely distributed. Their formation coincides with increased volcanic activity and continental weathering related to the breakup of Pangea, suggesting iron supply through one of these processes. We studied three Swiss shallow-marine iron oolites from Herznach, Windgällen and Erzegg, all from condensed sedimentary sequences of Middle to early Late Jurassic age, to constrain the source of iron to these rocks, combining radiogenic neodymium, strontium and stable iron isotope analyses. Leached authigenic neodymium isotope compositions, which appear to preserve the primary signature, serve as a tracer for the potential involvement of hydrothermal fluids in the formation of the iron oolites. The three iron oolite successions yield crustal Nd isotope compositions (εNd between − 9 and − 7), providing no evidence for the involvement of such fluids. It is, thus, more likely that iron in the sediments derived from detrital fluvial inputs. Strontium isotope compositions, which could potentially support these findings, point to metamorphic overprinting associated with Alpine thrusting. The light iron isotope signatures associated with Middle to early Late Jurassic condensed sequences, δ56Fe between − 1.49 and − 0.57‰, suggest that microbially-mediated iron reduction was also involved in generating these sediments.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The Jurassic Period exhibits high sedimentary facies diversity in the Alpine Tethys, resulting from major changes in plate tectonics, in paleoceanography and in paleoclimate (e.g. Bernoulli & Jenkyns, 1974; Dera et al., 2011; Norris & Hallam, 1995; Rais et al., 2007; Scotese, 1991; Ziegler, 1988). Peculiar oceanographic conditions were responsible for widespread deposition of condensed iron-rich sequences and hardgrounds during the Middle Jurassic (e.g. Bernoulli & Jenkyns, 1974; Jenkyns, 1971). A common feature of these deposits is their red or greenish color, originating from abundant iron minerals (e.g. Berner, 1969; Jenkyns, 1971). The source of iron (Fe) in these rocks is particularly enigmatic, given the low solubility of Fe in modern oxic seawater (e.g. Kraemer, 2004; Raiswell & Canfield, 2012; Worsfold et al., 2014). The particular geological setting suggests two possibilities for this source. First, the opening of Tethys was associated with seafloor spreading, leading to the suggestion of a hydrothermal source (e.g. Halliday & Mitchell, 1984; Holz, 2015; Scotese & Schettino, 2017). Second, a tropical climate may have caused enhanced weathering, suggesting continental Fe as another possible source (e.g. Donnadieu et al., 2006; Gehring, 1986a; Holz, 2015). Local enrichment of Fe and its incorporation into sediments is often associated with microbial activity, leading to locally reducing conditions within sediment porewaters and the mobilization of Fe in its reduced state (e.g. Dahanayake & Krumbein, 1986; Gehring, 1986b; Préat et al., 2008). Hence, irrespective of the source of Fe, redox related Fe cycling may have been involved in the formation of these iron-rich condensed sequences (e.g. Dahanayake & Krumbein, 1986; Gehring, 1985, 1986b; Glasauer et al., 2013; Kennedy et al., 2003; Salama et al., 2013).

Iron oolites are characteristic Fe-rich condensed sediments of Middle Jurassic age, and are widely distributed across Europe (e.g. Collin et al., 2005; Gehring, 1989). Iron oolites mainly represent condensed sequences, with low detrital sediment supply and low net sedimentation, that have formed in a shallow-marine setting (e.g. Burkhalter, 1995; Clement et al., 2020; Dollfus, 1961; Föllmi, 2016; Heikoop et al., 1996). Iron ooid formation and ooid sedimentation may geographically coincide, but sedimentary redistribution of iron ooids has also been suggested to occur (autochthonous and allochthonous iron oolites, respectively; e.g. Bhattacharyya & Kakimoto, 1982; Brunner, 1999; Harder, 1978; Siehl & Thein, 1989). Iron ooid formation today is restricted to isolated environments, so that it remains unclear how Fe-rich ooids could form pervasively in the Jurassic. Modern iron ooids are known from volcanic settings, in Mahengetang, Indonesia (less than 4.5 ka; Heikoop et al., 1996), and Panarea Island, Italy (actively forming; Di Bella et al., 2019), suggesting a hydrothermal Fe source for both deposits. No evidence for microbially-mediated Fe cycling has been found for these modern iron ooids but it cannot be excluded.

In this study we seek to test the two aforementioned hypotheses for the origin of Fe in Middle to lowermost Upper Jurassic iron-rich sedimentary rocks. We use a variety of geochemical tools, including radiogenic Nd (143Nd/144Nd), Sr (87Sr/86Sr) and stable Fe isotope variations (δ56Fe), to investigate the origin of Fe in Tethyan iron oolites and their ooid constituents. Contrasting with stable Fe isotope compositions, radiogenic Nd and Sr composition can provide robust information on fluid sources involved in the formation of marine sedimentary phases.

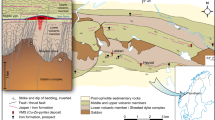

2 Studied iron oolites

Three iron oolite dominated condensed successions of Middle to earliest Late Jurassic age were studied, deriving from two different paleo-depositional realms: the iron oolites from Herznach (Herznach Member, Ifenthal Formation) were deposited on the Jura platform, while the Blegi Iron Oolite from Windgällen (Reischiben Formation) and the Planplatte Iron Oolite from Erzegg (Erzegg Formation) formed on the northern Tethyan shelf of the Helvetics (Fig. 1). Detailed information about the sampling locations is given in Table 1.

2.1 Iron oolites from Herznach

The Herznach region lies at the southern margin of the Tabular Jura Mountains in northwestern Switzerland (Diebold et al., 2005, 2006). Post-depositional burial temperatures prevailing in the area barely exceeded 100 °C (Frei, 1952; Gehring & Heller, 1989; Mazurek et al., 2006). Higher burial temperatures of 110–120 °C were recently reported for Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous dolomite veins (Looser et al., 2019), but whether these temperatures affected the Middle to lowermost Upper Jurassic iron oolites remains unclear. The Middle Jurassic succession in the Jura Mountains consists of several formations containing condensed iron oolite horizons (e.g. Bitterli-Dreher, 2012; Burkhalter, 1996). The studied iron oolite horizons of the Sissach Member (Passwang Formation) and of the Herznach Member (Ifenthal Formation) both represent the top of a shallowing upward succession (e.g. Bitterli-Dreher, 2012; Bläsi, 1987; Burkhalter, 1996; Gygi, 2000; Fig. 2). The deposition of the lower Passwang Formation (Early Aalenian to Early Bajocian) was influenced by sea level fluctuations and subsidence, which resulted in the formation of siliciclastic and carbonate rocks, and iron oolite horizons at the top of most sequences (Burkhalter, 1996). The Sissach Member has a thickness of 5–15 m that accumulated in less than 3 Ma (Early to Middle Aalenian; Burkhalter, 1996; Diebold et al., 2006) and is considered a condensed sequence in the sense of Jenkyns (1971).

Stratigraphic profile of the eastern Jura Mountains and the autochthonous sediment cover of the Aar Massif. Formation names in bold indicate the studied iron oolite deposits. The Herznach area corresponds to the eastern facies type of the Jura Mountains; the Windgällen area to the northern facies type (autochthonous), and the Erzegg area to the intermediate facies type of the Axen nappe. The sediment thickness increases towards more southerly paleopositions in the Aar Massif, which is most likely due to increased subsidence in southern regions (Gisler et al., 2020). Modified after Diebold et al. (2005, 2006), Gisler and Spillmann (2011), Gisler et al. (2020), Wohlwend et al. (2022)

The iron oolite of the Herznach Member is a thin succession of iron oolitic marls and limestones of the Ifenthal Formation (e.g. Bitterli-Dreher, 2012; Gygi, 2000; Fig. 2). Syn-sedimentary tectonics resulted in a seafloor structure characterized by oceanic highs and lows (Bitterli, 1977; Gygi, 2000). The rich ammonite fauna suggests a late Early Callovian to late Early Oxfordian age for the member (e.g. Bitterli-Dreher, 2012; Gygi, 1981; Gygi & Marchand, 1982; Jeannet, 1951). With a maximum thickness of 5–6 m (Bitterli-Dreher, 2012), which accumulated in around 4 million years, the Herznach Member is also a condensed sequence. Iron has been suggested to derive from lateritic weathering of adjacent continental areas (Gygi, 1981), and has been suggested to have been mobilized and locally enriched by microbial activity (Gehring, 1985; Glasauer et al., 2013). Remnants of microbial iron enrichment processes within the ooids are documented in cortical layering of ramified μm-sized structures of biological origin (Figs. 3A and B). The iron oolites from Herznach consist of poorly sorted iron ooids, which are often shattered and act as nucleii for other ooids, indicating that this process occurred during the formation of the iron ooids. Ooids with a nucleus made of either tiny quartz crystals or calcite fragments are also found (Bühler, 1986). The various cores are surrounded by concentric layers of limonite or chamosite (Bühler, 1986), goethite and apatite (e.g. Burkhalter, 1995; Gehring, 1985, 1986a) or limonite and hematite (Bodmer, 1978). Only small amounts of pyrite have been found (0.1–0.3%; Bühler, 1986). Other frequently found minerals in the iron oolite deposits from Herznach are, in order of decreasing abundance, calcite, celestine, dolomite, gypsum and sphalerite (Frei, 1952).

A Principal component map and B Fe/C-ratio map of iron oolite sample from Herznach (H1), showing concentric layering of the iron ooid. C Magnetite cubes growing at the expense of flattened green chamositic iron ooids related to the Windgällen folding events (WG6). D Poorly sorted iron ooids with broken ooid fragments or polyooid as ooid nuclei document ooid transportation processes in the iron oolites from Erzegg (EE-P1). E View from Unteres Furggeli to the eastern Windgällen region. The black Blegi Iron Oolite band (marked red) is clearly visible in the field. F Sampled profile at Erzegg, with interlayers of iron oolite and marls with clay schists (see profile in Fig. 4)

2.2 Blegi Iron Oolite from Windgällen

The Blegi Iron Oolite from Windgällen is a subordinate member of the Reischiben Formation (Brückner & Zbinden, 1987; Hantke and Brückner, 2011). It is composed of chamosite ooids embedded in a micritic limestone matrix (Déverin, 1945; Dollfus, 1965; Hänni, 1999). The iron oolite also contains clay detritus with areas of chamosite and pyrite crystals, as well as some fossils such as ammonites, belemnoids, bivalves, small gastropods, foraminifera and bryozoa (Déverin, 1945). The age of the Blegi Iron Oolite has been constrained using the ammonite fauna, which suggests stratigraphic ages of Late Bajocian to Early Callovian (e.g. Dollfus, 1961). The Blegi Iron Oolite has a maximal thickness of 3.5 m, accumulated over about 5 Myr (Dollfus, 1965), and is therefore also a condensed sequence. Despite its small thickness, the Blegi Iron Oolite is prominent in the Windgällen area (Fig. 3E). The deposition of the sediments containing the Blegi Iron Oolite was controlled by syn-sedimentary tectonics (Dollfus, 1965; Trümpy, 1949; Ziegler, 1993). In Early Jurassic times, the Windgällen depositional site was located in a continental setting on the Alemannic Land, the Windgällen Ridge (Trümpy, 1949). Marine transgression affected the Windgällen Ridge only in Late Bajocian times, which is expressed in the absence of the entire Triassic, and Lower Jurassic strata in the region (e.g. Dollfus, 1965; Fig. 2). The iron ooids formed on the flooded Windgällen Ridge, a pelagic rise, at depths greater than the wave base and therefore in a tranquil setting (e.g. Kugler, 1987). Temperature and pressure conditions in the Windgällen region exceeded those at Herznach, with maximal temperatures of 305–410 °C and pressures of 2.1 \(\pm\) 0.7 kbar (Schenker, 1980, 1986). Intense two-phase folding related to the Windgällen anticline resulted in ooid deformation and new mineral growth, including the decomposition of chamosite ooids and the formation of new plagioclase, quartz and magnetite (Heim, 1878; Déverin, 1945; Baker, 1964; Tan, 1976; Röthlisberger, 1990; Burkhard, 1999; Hantke and Brückner, 2011; Fig. 3C).

2.3 Planplatte Iron Oolite from Erzegg

The Upper Bajocian to Lower Oxfordian Erzegg Formation consists of a thick succession of marl and clay schists (Brunner, 1999; Gisler et al., 2020; Staeger et al., 2020; Tröhler, 1966; Fig. 4). The strongly Fe-impregnated marls show an interval with rare, laterally discontinuous intercalations of iron oolites (Brunner, 1999), the informally-named Planplatte Iron Oolite of Early to Middle Callovian age (Gisler et al., 2020; Tröhler, 1966). The Planplatte Iron Oolite is a few meters thick and crops out over a length of about 6 km, extending from the Erzegg in the east, over the Balmeregghorn, to the Planplatte in the west (Brunner, 1999; Tröhler, 1966; Fig. 3F). The iron ooids initially likely formed in a shallow-marine setting, where iron enrichment may have occurred in a reducing milieu at the sediment–water interface (Brunner, 1999). Iron ooids formed in slightly agitated waters in a clay-rich sediment. Occasional storm events shattered the iron ooids and transported them to the south into deeper and more argillaceous environments. Those iron oolitic claystones were later transformed into the schists of the Erzegg Formation (Brunner, 1999). This allochthonous origin of iron ooids of the Planplatte Iron Oolite (Brunner, 1999; Tröhler, 1966) contrasts with the autochthonous iron ooid formation of the Blegi Iron Oolite.

Typical minerals found in the Planplatte Iron Oolite are goethite, chamosite, calcite, clays, hematite, magnetite, siderite, dolomite, quartz, pyrite and muscovite (Tröhler, 1966). The core of the iron ooids are either broken ooids, several ooids (polyooid) or chamositic fragments of echinoderms (Brunner, 1999; Tröhler, 1966; Fig. 3D). The ooids themselves consist of goethite or chamosite (Brunner, 1999; Tröhler, 1966), but apatite has also been reported in the ooid cortex (Brunner, 1999). The clay minerals are believed to be mainly of detrital origin, but diagenetic formation is also possible (Tröhler, 1966). Angular to sub-rounded quartz grains in the matrix support the concept of detrital input and proximal sedimentation. The Erzegg area has been less affected by Alpine metamorphism than the Windgällen, with maximum temperature conditions of 250 °C at pressures of about 2 kbar (Berger et al., 2017; Frey et al., 1980; Herwegh et al., 2017).

3 Sampling and methods

We sampled two iron oolite horizons from Herznach (Herznach Member and Sissach Member), one from Windgällen (Blegi Iron Oolite) and several horizons of a detailed stratigraphic section of the Erzegg Formation at Erzegg (Table 1).

Neodymium, strontium and iron isotope compositions were measured on leached iron oolite samples from Herznach, Windgällen and Erzegg. Representative rock samples of each outcrop were collected and sawn into small blocks, avoiding weathered or fractured material and targeting representative portions in terms of ooid abundance. Appropriate rock cubes were hydraulically crushed and subsequently ground in an agate mill. These powders were reductively leached in the clean lab facilities at ETH Zürich, targeting authigenic sedimentary Fe-phases (Blaser et al., 2016). Rock powders (40–60 mg) were reacted with 5 ml of 1.5% acetic acid, 0.005 M hydroxylamine hydrochloride and 0.003 M EDTA (buffered to pH ~ 4 with ammonia) for 30 min on a vortex shaker. After centrifugation, 4 ml of the supernatant leach solution was pipetted off and dried down. The leachates were subsequently fluxed with 1 ml of concentrated HNO3 for at least 12 h. Sample stock solutions were prepared in 2 M HNO3 or 6 M HCl.

Elemental concentrations in the leachates were measured using a Thermo-Fisher Element XR ICP-MS at ETH Zürich, as described by Vance et al. (2016). Dilute stock solutions were run in 2% HNO3 doped with 1 ppb In for internal normalization. Concentrations were calculated relative to an in-house standard. Two secondary standards were run to assess precision and accuracy of the reported concentrations: NRC Canada river standard SLRS-6, and the USGS shale standard SGR-1. Accuracy of the reported concentration data (versus certified or literature values) ranges between 2 and 13%, precision is better than 5% (1 SD, Table 2).

Based on Nd concentrations from the Element runs, aliquots of the leachates were spiked with appropriate amounts of a mixed 149Sm/150Nd spike. Strontium and rare earth elements (REE) were separated from matrix elements and each other on cation resin (AG 50W-X8, 200–400 mesh, 1 ml resin bed). Neodymium and Sm were subsequently isolated from each other and all other REEs on LN spec resin in dilute HCl (50–100 µm, 0.3 ml resin bed; Pin & Zalduegui, 1997). Strontium was further purified on Sr spec resin (50–100 µm, 0.1 ml resin bed; Deniel & Pin, 2001).

Iron isotope compositions were obtained for a selection of seven sample leachates of the three studied iron oolite lithologies (Table 4). A sample aliquot containing 1 µg of Fe was spiked with a 57Fe-58Fe double spike (to achieve a sample/spike ratio of ~ 1) and processed through an anion column containing AG-MP-1M resin. The matrix and Cu were eluted in 7 M HCl with trace peroxide, prior to the elution of Fe in 1 M HCl. For all isotope measurements, the purified elements were fluxed in 14.5 M HNO3 with 30% hydrogen peroxide (ratio 9:1, 1 ml solution) to oxidize organic compounds deriving from the resins. Iron procedural blanks (< 0.1 ng) were insignificant compared to processed sample Fe.

Neodymium, Sr and Fe isotopes, as well as spiked Sm isotope ratios, were measured individually on a Thermo-Fisher Neptune Plus MC-ICP-MS. Instrumental mass bias correction followed Vance and Thirlwall (2002) for Nd and Thirlwall (1991) for Sr, using a 86Sr/88Sr ratio of 0.1194. Neodymium and Sr isotope compositions were renormalized to the accepted literature values of La Jolla and NIST SRM 987 (Thirlwall, 1991). Repeated standard measurements during each session yielded external error estimates < 15 ppm for 143Nd/144Nd (2 SD) and < 14 ppm for 87Sr/88Sr (2 SD). Samples were mostly run at similar concentrations as standards, yielding similar internal errors for both (Tables 3 and 4). Procedural blanks were < 30 pg for Nd and Sr and < 10 pg for Sm and were negligible compared to sample sizes.

Measured radiogenic Nd and Sr isotope compositions were corrected for ingrowth of 143Nd and 87Sr, respectively, since their time of formation (e.g. Faure & Mensing, 2005, and references therein) using biostratigraphic age constraints (see Sect. 2). The age uncertainty of the studied iron oolites has little effect on these corrections, less than the uncertainty on the measurements. Therefore, an intermediate age was used for all samples at one location (Tables 3 and 4). Age corrections on 143Nd used Sm/Nd ratios from isotope dilution, that are associated with uncertainties < 1‰. The uncertainty on Rb/Sr ratios measured on the Element was conservatively estimated to be 10%. This uncertainty was propagated through the age correction. Samples with elevated Rb/Sr were not processed for Sr isotope compositions. Maximal uncertainties on the age corrected 87Sr/86Sr ratio correspond to less than 2 ⋅ 10–5. Neodymium isotope compositions are reported in epsilon-notation relative to the Chondritic Uniform Reservoir (CHUR) at the time of sediment formation. The CHUR has a present-day 143Nd/144Nd ratio of 0.512638 and 147Sm/144Nd of 0.1967 (Jacobsen & Wasserburg, 1980).

Iron isotopic compositions, δ56Fe, are reported in delta notation relative to the standard IRMM-014, with an uncertainty of \(\pm\) 0.08‰ (2 SD) based on the long-term reproducibility of secondary standard NIST-3126 (Sun et al., 2021).

4 Results

The analyzed iron oolites consist of authigenic iron and carbonate minerals as well as detrital silicates (see Sect. 2). Success in selectively leaching the key phases of interest, authigenic iron minerals, can be assessed using elemental concentrations (Table 2). More specifically, we use Fe to track the leaching of iron minerals, Ca for carbonates, and Al for detritus (see discussion in Sect. 5.1). The iron oolite leachates from Herznach, Windgällen and Erzegg yield molar Ca/Fe ratios between 1 and 67 and Fe/Al ratios between 1 and 88. Al/Nd ratios were usually below 900.

Initial Sr isotope ratios at the time of formation of the iron oolites are more radiogenic than contemporary seawater (Table 3), yielding 0.707290 \(\pm\) 0.000013 (n = 2), 0.711820 \(\pm\) 0.000013 (n = 2) and 0.709486 \(\pm\) 0.000014 (n = 12) for Herznach, Windgällen and Erzegg, respectively. Initial εNd range between − 9 and − 7 except for sample EE-P23 (εNd = − 10.1). Measured δ56Fe are between − 1.5 and − 0.6‰ (Table 4). Authigenic Fe isotope compositions, corrected for detrital contributions, are marginally different from measured Fe isotope compositions (< 0.05‰; Table 4). These detrital corrections are based on three assumptions: (i) all sample Al is detrital, (ii) detrital contributions have a Fe/Al ratio like the continental crust (mass ratio of ~ 0.481; Rudnick et al., 2003) and (iii) a crustal Fe isotope composition (0.1‰; Beard et al., 2003).

5 Discussion

5.1 Limitations of the leaching approach

The iron oolites are composed mainly of a carbonate fraction and of iron ooids. It is therefore possible that the carbonate and the ooids carry different radiogenic isotope signatures if, for instance, the carbonate reflects mostly marine carbonate shells, while the iron ooids formed during mixing of hydrothermal fluids and seawater. Such a formation process has been suggested for modern iron ooids at Panarea in the Tyrrhenian Sea (Di Bella et al., 2019). The reductive leach used here was applied prior to carbonate removal to avoid leaching detrital material (Blaser et al., 2016). Although this resulted in generally low Al/Nd ratios (< 900 molar ratio, < 170 mass ratio; see Sect. 5.3), it failed to isolate a strongly Fe-enriched phase given Ca/Fe ratios of 1–67 (Table 2; Fig. 5A). However, there is no correlation between leached Ca/Fe ratios and Nd isotope compositions (Fig. 5A). Thus, though isotope variations between Fe-rich and Ca-rich portions of the iron oolites cannot be completely ruled out, it seems rather unlikely.

Leached Nd isotope composition vs. leached A Ca/Fe and B Al/Nd ratios. The solid blue lines are linear regressions to the data with calculated coefficients of determination (r2). The linear regression model excluded the clay-dominated sample EE-P23. The dashed black line in B depicts the Al/Nd threshold of ~ 535 as an indication of authigenic Nd isotope signatures (Huang et al., 2021). The lack of correlation between εNd and Ca/Fe suggests that Fe-rich sediment phases (e.g. goethite, chamosite) are not isotopically distinct from Ca-rich phases (e.g. calcite, dolomite). Similarly, the lack of correlation between εNd and Al/Nd suggests that the authigenic phases extracted by leaching are not contaminated by detrital contributions

5.2 Potential for metamorphic overprinting of strontium isotope compositions

Initial Sr isotope ratios at the time of formation of the iron oolites are more radiogenic than seawater at that time (Table 3; Fig. 6) yielding 0.707290 \(\pm\) 0.000013 (n = 2), 0.711820 \(\pm\) 0.000013 (n = 2) and 0.709486 \(\pm\) 0.000014 (n = 12) for Herznach, Windgällen and Erzegg, respectively. These offsets are most likely explained either by: (i) Sr isotope variability in coastal seawater at that time; (ii) allochthonous iron ooid formation on land and later transportation to the depositional basin or; (iii) post-sedimentary overprinting of Sr isotope compositions due to metamorphic fluids.

Reductively leached Sr isotope compositions of the Swiss iron oolites from Herznach, Windgällen and Erzegg compared to the Jurassic seawater Sr isotope curve (with a 95% confidence interval; Wierzbowski et al., 2017). Leached Sr isotopes are more radiogenic than contemporary seawater due to metamorphic overprint (Sect. 5.2). Error bars on ages reflect available age constraints (see Tables 1 and 3). Ages after Gradstein et al. (2012). Aal. Aalenian, Bj. Bajocian, Bt. Bathonian, Cl. Callovian, Oxf. Oxfordian, Kimm. Kimmeridgian, Tith. Tithonian, Berri. Berriasian

Due to the long residence time of Sr in seawater of ~ 3 Ma, significant isotopic variability is not expected (e.g. Hodell et al., 1990). Previous work has shown that the Sr isotope signature in coastal areas can deviate from the global open marine signature by up to about 0.00025 (e.g. El Meknassi et al., 2018, 2020; Huang et al., 2011; Ingram & Sloan, 1992). Such local offsets may be related to river runoff, which is isotopically highly variable (e.g. Pearce et al., 2015), or, although this seems less likely based on global Sr budgets (e.g. Paytan et al., 2021), to groundwater or diagenetic Sr fluxes. The offsets from contemporary seawater observed at Windgällen and Erzegg are, however, much larger, on the order of ~ 0.002 to ~ 0.005. Such offsets could only be explained if the sediments were formed in highly restricted basins, which is inconsistent with paleogeographic reconstructions (e.g. Scotese & Schettino, 2017; van Hinsbergen et al., 2020; Ziegler, 1993).

A continental origin of iron ooids has previously been proposed for the Paris Basin, where iron ooids may have been derived from latosols (Siehl & Thein, 1989). In Swiss iron oolites, the presence of fragmented iron ooids also imply transportation processes (e.g. Brunner, 1999; Gehring, 1989; Fig. 3D). However, such processes can also occur in marine environments affected by strong ocean currents (e.g. Gehring, 1989; Rais et al., 2007). Although a continental origin of the iron ooids cannot be fully precluded, it seems unlikely. Therefore, the radiogenic Sr isotope compositions of the studied Swiss iron oolites point to a metamorphic, fluid-related overprint, although marine Sr isotope signatures have been measured in some marine sediments in the region (Doldenhorn; Burkhard & Kerrich, 1990).

The studied Swiss iron oolites experienced different metamorphic pressures and temperatures (see Sect. 2). The Sr isotope system is known to be more susceptible to metamorphic alteration than Nd (Hradetzky & Lippolt, 1993; Jenkin et al., 2001; Schaltegger et al., 1994). Metamorphic fluids, usually radiogenic in Sr, are preferentially focused along thrusts where they affect adjacent rocks within a few meters to a few hundred meters (e.g. Burkhard & Kerrich, 1990; Burkhard et al., 1992; Hradetzky & Lippolt, 1993; Huon et al., 1994; Kirschner et al., 1999, 2003). Remnants of metamorphic fluids are documented from fluid inclusion studies for the Erzegg and Windgällen (e.g. Miron et al., 2013; Mullis et al., 1994). Whether the chamosite decomposition in the Windgällen was associated with metamorphic fluids is unclear (Déverin, 1945). Thrusting is documented in the vicinity of the iron oolites from Herznach, Windgällen and Erzegg (Brückner & Zbinden, 1987; Diebold et al., 2005, 2006; Gisler et al., 2020; Hantke and Brückner, 2011; Staeger et al., 2020), so that Sr isotope compositions have likely been altered.

5.3 Neodymium isotope compositions

There is no universally applicable approach for the identification of significant detrital contributions to authigenic Nd, given the diversity of depositional environments and diagenetic processes. A threshold ratio for unaffected authigenic Nd isotope signatures has been suggested for Quaternary marine sediments corresponding to a molar Al/Nd ratio of ~ 535 (mass ratio of 100; Huang et al., 2021). Apart from a few samples (EE-P4, EE-P23 and EE-P32), the leachates show Al/Nd ratios close to this threshold (Fig. 5B). Sample EE-P23 is a clay-dominated sample, which produced a distinctly high Al/Nd ratio and a low εNd of − 10.1, implying that this signature may not be fully authigenic. All further Nd isotope compositions of the iron oolites from Herznach, Windgällen and Erzegg are similar and range between − 9 and − 7, likely reflecting contemporary seawater (Fig. 7; Dera et al., 2015). In addition, leached Nd isotopes are not correlated with Al/Nd ratios, suggesting that detrital Nd does not affect the authigenic signatures (Fig. 5B).

Authigenic Nd isotope composition of the iron oolites from Herznach, Windgällen and Erzegg compared to the Tethyan Jurassic seawater Nd isotope curve (Dera et al., 2015) and proximal basins. Leached compositions are consistent with contemporary seawater, providing no evidence for the involvement of hydrothermal fluids. Error bars on ages reflect available age constraints (see Tables 1 and 4). Ages after Gradstein et al. (2012). Hett. Hettangian, Sine. Sinemurian, Pliensb. Pliensbachian, Aal. Aalenian, Bj. Bajocian, Bt. Bathonian, Cl. Callovian, Oxf. Oxfordian, Kimm. Kimmeridgian, Tith. Tithonian

These low Nd isotope compositions do not argue for the involvement of hydrothermal fluids in the formation of iron oolites. Indeed, they are similar to previous reconstructions of seawater signatures in the Middle Jurassic Tethys (Dera et al., 2015). Slight variations in εNd between samples are consistent with generally open depositional basins and can, for instance, be explained by isotopically different fluvial Nd inputs (Dera et al., 2015). Comparable conclusions have already been drawn for the Late Jurassic Swabian epicontinental basin, opening southward into the Helvetic facies belt (e.g. Olivier & Boyet, 2006; Stille & Fischer, 1990), and for Early Jurassic sediments of the Paris Basin (e.g. Dera et al., 2009; Fig. 7). Such an open basin model also suggests that the seawater was oxygenated, as is also documented by the rich fauna in iron oolites (e.g. Dollfus, 1961; Gygi, 2000). Overall, the authigenic neodymium isotope signatures in the studied iron oolites are crustal, and do not provide evidence for significant hydrothermal contributions of Nd. A riverine source of iron, derived from weathering of the adjacent hinterland, has also been proposed by other studies (e.g. Baioumy et al., 2017; Chowns, 1966; Gehring, 1986a; Li et al., 2021).

5.4 Iron isotope compositions

Iron supplied with the sediment load of rivers must be locally enriched to form Fe-rich condensed sequences. Elevated organic matter contents are often associated with iron-rich sediments (e.g. Lalonde et al., 2012), supporting the concept that Fe reduction may occur in restricted environments with oxygen depletion. Gehring (1985) proposed an iron ooid formation model in the vicinity of organic matter. Such an involvement of microbes in iron cycling should be reflected in iron isotope compositions. Microbially-mediated Fe(III) reduction preferentially utilizes the light 54Fe compared to 56Fe (Beard et al., 1999; Ellwood et al., 2015), resulting in low δ56Fe values, usually lower than average crustal rocks with δ56Fe of 0.1‰ (Beard et al., 2003).

The light δ56Fe isotope values, between − 1.49 and − 0.57‰, of the iron oolites are consistent with the involvement of microbial processes. Based on Nd isotopes, this Fe is likely supplied by rivers. Detrital Fe transported by rivers is expected to have an Fe isotope signature similar to that of average crustal rocks (0.1‰; Beard et al., 2003). Reductive dissolution of sedimentary Fe involving microbial processes would release isotopically light Fe to pore waters, subsequently incorporated into iron ooids. However, it remains unclear whether a locally reductive milieu is a general feature of the “ooid factory” or if reduction is restricted to the iron ooids themselves, since remnants of microbial structures inside the ooids are ambiguous (Burkhalter, 1995; Dahanayake & Krumbein, 1986; Gehring, 1986b).

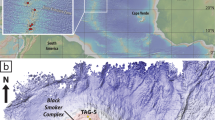

5.5 Iron oolite formation model

Sedimentary condensation tends to occur on topographic highs and in an active hydrodynamic regime, where the accumulation rate is low due to processes such as winnowing, erosion, bypassing and reworking (Föllmi, 2016; Gómez & Fernández-López, 1994; Jenkyns, 1971; Fig. 8). Both conditions are relevant for the three iron oolite deposits in Switzerland. A key factor controlling the formation of iron oolites was likely syn-sedimentary tectonics, which resulted in the subsidence of the European Tethyan continental margin, forming submarine plateaus and basins (e.g. Bitterli, 1977; Trümpy, 1949, 1952; Ziegler, 1993). Such plateaus are influenced by strong ocean currents that sweep away sediments, thus decreasing the accumulation rate (e.g. Eberli et al., 2010; Fürsich, 1979; Heezen & Hollister, 1964). This condensation process is likely intensified by presumably little, but not zero, terrigenous sediment input. Temporarily less intense ocean currents favored the deposition of clay minerals at the depositional site (Reineck & Singh, 2012, and references therein), supporting the enrichment of organic carbon, since clay minerals are attractive sites for both iron and organic matter (e.g. Kennedy et al., 2002; Oades, 1988). That clay minerals are relevant for the formation of iron oolites is also supported by their presence in all studied Swiss iron oolites. The same processes are also documented in the Middle to Late Jurassic condensed sequences of the northern continental margin of the Iberian Basin (García-Frank et al., 2012), and in the Late Bajocian to Tithonian condensed Rosso Ammonitico Veronese of the southern continental margin formed on the Trento Plateau (Bernoulli et al., 1979; Martire, 1992, 1996; Préat et al., 2006).

Schematic sketch for the formation of ancient and modern iron ooids. The formation of Jurassic iron ooids results from the coupling of sedimentary organic carbon enrichment (due to the delivery of carbon associated with detrital clays), microbially-mediated Fe cycling of sediment-sourced Fe, and sedimentary condensation processes related to agitated hydrodynamics. The variation in authigenic εNd between − 9 and − 7 of the studied iron oolites likely reflects variations in the weathered continental source areas. In contrast to ancient iron ooids, modern iron ooids form in a volcanic setting with intense submarine hydrothermal activity (Di Bella et al., 2019). Average continental and hydrothermal δ56Fe, the latter including mid-ocean ridge hydrothermal fluids, are from Beard et al. (2003). Continental εNd (− 10 to − 8) represents a range for four modern Swiss rivers (Rickli et al., 2013), which is similar to the average of detrital sedimentary rocks aged 0–200 Ma (− 10 ± 8, 1 SD; compiled in Garçon, 2021) and averaged world river suspended loads (− 11 ± 4, 1 SD; compiled in Garçon, 2021). Hydrothermal εNd represents averaged compositions of mid-ocean ridge basalts (± 1 SD; compiled in Gale et al., 2013). Middle Jurassic Tethyan Nd isotope composition cover the temporal variations given in Dera et al. (2015)

Similarly, the only known place where iron ooids are actively forming today is in a dynamic shelf setting, northeast of Panarea Island in the Tyrrhenian Sea (Di Bella et al., 2019). Several paleoshorelines document sea level changes related to global sea-level fluctuations and long-term uplift at the depositional site (Chappell & Shackleton, 1986; Di Bella et al., 2019; Lucchi, 2009; Lucchi et al., 2007). Fluctuations in sea level shift the zones of deposition and erosion in marine settings, resulting in oscillating sediment accumulation and erosion (e.g. Lewis, 1973; Paulay & McEdward, 1990; Swift & Thorne, 1991). Though rapid sea-level variations can account for low accumulation rates, this seems unlikely to be the sole process for the formation of ancient iron oolites since their formation spans several Myrs (Rais et al., 2007). Our Fe isotope data suggest that microbially-mediated Fe cycling contributed to the formation of iron oolites, whilst Nd isotope compositions provide evidence against hydrothermally sourced Fe.

6 Conclusion

Iron-rich condensed sequences are characteristic of the Middle Jurassic Period, and formed during significant changes in plate configuration and climate (e.g. Dera et al., 2011; Rais et al., 2007; Ziegler, 1988). The formation of condensed sequences coincides with increased hydrothermal activity and increased continental runoff related to the breakup of Pangea (e.g. Halliday & Mitchell, 1984; Holz, 2015), suggesting that one of these processes could be the source of iron. The breakup of Pangea formed a peculiar submarine relief, with plateaus and basins controlled by syn-sedimentary tectonics (e.g. Trümpy, 1949; Ziegler, 1993). Iron ooids accumulated on the plateaus or highs, where low sedimentation and high erosion rates were influenced by ocean currents and partly by sea level fluctuations, leading to sedimentary condensation.

Leached authigenic Nd isotope compositions yield constraints on the origin of Fe in the studied iron oolite successions in Switzerland. The crustal Nd isotope signature of the iron oolites suggests that the involvement of hydrothermal fluids in their formation is unlikely, and that Fe is instead derived from detrital material supplied by rivers. This contrasts with modern iron ooids, where the source of Fe is presumably hydrothermal (Di Bella et al., 2019; Sturesson et al., 2000). This difference between the ancient and modern Fe source might suggest that either iron ooid formation switched from a crustal setting in the Middle Jurassic to a hydrothermal setting today, or that iron ooids can form in different environments.

Aqueous iron concentrations are generally extremely low in the ocean, but increase in reducing settings due to microbially-mediated Fe reduction, suggesting that microbial mediation is an important process to locally enrich iron. Signs of microbial iron enrichment processes are still preserved in the Middle to earliest Late Jurassic iron oolites and documented in negative Fe isotope signatures.

Availability of data and materials

All discussed new data generated during this study are included in this publication.

Abbreviations

- Fe:

-

Iron

- Cu:

-

Copper

- Rb:

-

Rubidium

- Sr:

-

Strontium

- Nd:

-

Neodymium

- Sm:

-

Samarium

- REE:

-

Rare earth elements

- CHUR:

-

Chondritic Uniform Reservoir

- HNO3 :

-

Nitric acid

- HCl:

-

Hydrochloric acid

- EDTA:

-

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- SEM:

-

Scanning Electron Microscopy

- (MC-)ICP-MS:

-

(Multicollector) inductively coupled plasma mass spectroscopy

- NRC Canada:

-

National Research Council Canada

- USGS:

-

United States Geological Survey

- NIST:

-

National Institute of Standards and Technology

- IRMM:

-

Institute for Reference Materials and Measurements

- H:

-

Herznach

- WG:

-

Windgällen

- EE:

-

Erzegg

- Gr:

-

Gross Ruchen

- USM-I:

-

Lower Freshwater Molasse I

- E:

-

Early

- M:

-

Middle

- L:

-

Late

- U:

-

Upper

- Hett.:

-

Hettangian

- Sine.:

-

Sinemurian

- Pliensb.:

-

Pliensbachian

- Aal.:

-

Aalenian

- Bj.:

-

Bajocian

- Bt.:

-

Bathonian

- Cl.:

-

Callovian

- Oxf.:

-

Oxfordian

- Kimm.:

-

Kimmeridgian

- Tith.:

-

Tithonian

- Berri.:

-

Berriasian

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- r2 :

-

Coefficient of determination

References

Baioumy, H., Omran, M., & Fabritius, T. (2017). Mineralogy, geochemistry and the origin of high-phosphorus oolitic iron ores of Aswan, Egypt. Ore Geology Reviews, 80, 185–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oregeorev.2016.06.030

Baker, D.W. (1964). The Windgällen Fold: A restudy of a classical Alpine structure. Zurich, Switzerland, ETH Zurich, Diploma Thesis, unpublished, 79pp.

Beard, B. L., Johnson, C. M., Cox, L., Sun, H., Nealson, K. H., & Aguilar, C. (1999). Iron isotope biosignatures. Science, 285(5435), 1889–1892. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.285.5435.1889

Beard, B. L., Johnson, C. M., Skulan, J. L., Nealson, K. H., Cox, L., & Sun, H. (2003). Application of Fe isotopes to tracing the geochemical and biological cycling of Fe. Chemical Geology, 195(1–4), 87–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0009-2541(02)00390-X

Berger, A., Wehrens, P., Lanari, P., Zwingmann, H., & Herwegh, M. (2017). Microstructures, mineral chemistry and geochronology of white micas along a retrograde evolution: An example from the Aar massif (Central Alps, Switzerland). Tectonophysics, 721, 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2017.09.019

Berner, R. A. (1969). Goethite stability and the origin of red beds. Geochimica Et Cosmochimica Acta, 33(2), 267–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(69)90143-4

Bernoulli, D., & Jenkyns, H.C. (1974). Alpine, Mediterranean, and Central Atlantic Mesozoic facies in relation to the early evolution of the Tethys. In R.H. Dott, & R.H. Shaver (Eds.), Modern and ancient geosynclinal sedimentation. Special Publication 19, Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists, Tulsa, OK; 129–160. doi: https://doi.org/10.2110/pec.74.19.0129.

Bernoulli, D., Caron, C., Homewood, P., Kälin, O., & van Stuijvenberg, J. (1979). Evolution of continental margins in the Alps. Schweizerische Mineralogische Und Petrographische Mitteilungen, 59, 165–170.

Bhattacharyya, D. P., & Kakimoto, P. K. (1982). Origin of ferriferous ooids; an SEM study of ironstone ooids and bauxite pisoids. Journal of Sedimentary Research, 52(3), 849–857. https://doi.org/10.1306/212F8071-2B24-11D7-8648000102C1865D

Bitterli, P. (1977). Sedimentologie und Palaeogeographie des oberen Doggers im zentralen und nördlichen Jura. Mit einem Beitrag zum Problem der Eisenoolithbildung. Basel, Switzerland, University of Basel, Inauguraldissertation, 132pp.

Bitterli-Dreher, P. (2012). Die Ifenthal-Formation im nördlichen Jura. Swiss Bulletin for Applied Geology, 17(2), 93–117. https://doi.org/10.5169/seals-349246

Blaser, P., Lippold, J., Gutjahr, M., Frank, N., Link, J. M., & Frank, M. (2016). Extracting foraminiferal seawater Nd isotope signatures from bulk deep sea sediment by chemical leaching. Chemical Geology, 439, 189–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2016.06.024

Bläsi, H. R. (1987). Lithostratigraphie und Korrelation der Doggersedimente in den Bohrungen Weiach, Riniken Und Schafisheim. Eclogae Geologicae Helvetiae, 80(2), 415–430. https://doi.org/10.5169/seals-166004

Bodmer, P. (1978). Geophysikalische Untersuchung der Eisenoolithlagerstätte von Herznach-Wölflinswil. In Die Eisen- und Manganerze der Schweiz, Beiträge zur Geologie der Schweiz – Geotechnische Serie, 13/11 (pp. 1–63). Schweizerische Geotechnische Kommission.

Brückner, W., & Zbinden, P. (1987). LK 1192 Schächental. Geological Atlas of Switzerland 1:25 000, Map 83. Wabern: Federal Office of Topography swisstopo.

Brunner, B. (1999). Geologische Untersuchungen im Gebiet Tannalp—Rotsandnollen—Jochpass—Engstlenalp, Kanton Obwalden: mit Schwerpunkt Sedimentologie des Doggers und Bildung von Eisenoolithen der Erzegg. Zurich, Switzerland, ETH Zurich, Diploma Thesis, unpublished, 73pp.

Bühler, R. (1986). Bergwerk Herznach: Erinnerungen an den Fricktaler Erzbergbau. AT Verlag.

Burkhalter, R. M. (1995). Ooidal ironstones and ferruginous microbialites: Origin and relation to sequence stratigraphy (Aalenian and Bajocian, Swiss Jura mountains). Sedimentology, 42(1), 57–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3091.1995.tb01271.x

Burkhalter, R. M. (1996). Die Passwang-Alloformation (unteres Aalénien bis unteres Bajocien) im zentralen und nördlichen Schweizer Jura. Eclogae Geologicae Helvetiae, 89(3), 875–934. https://doi.org/10.5169/seals-167927

Burkhard, M. (1999). Strukturgeologie und Tektonik im Bereich AlpTransit. In S. Löw, R. Wyss, U. Briegel, B. Oddson, & L. Schlickenrieder (Eds.), Vorerkundung und Prognose der Basistunnels am Gotthard und am Lötschberg (pp. 45–57). Balkema.

Burkhard, M., & Kerrich, R. (1990). Fluid-rock interactions during thrusting of the Glarus nappe—evidence from geochemical and stable isotope data. Schweizerische Mineralogische Und Petrographische Mitteilungen, 70, 77–82.

Burkhard, M., Kerrich, R., Maas, R., & Fyfe, W. (1992). Stable and Sr-isotope evidence for fluid advection during thrusting of the Glarus nappe (Swiss Alps). Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 112, 293–311. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00310462

Chappell, J., & Shackleton, N. J. (1986). Oxygen isotopes and sea level. Nature, 324, 137–140. https://doi.org/10.1038/324137a0

Chowns, T. M. (1966). Depositional environment of the Cleveland Ironstone series. Nature, 211, 1286–1287. https://doi.org/10.1038/2111286a0

Clement, A. M., Tackett, L. S., Ritterbush, K. A., & Ibarra, Y. (2020). Formation and stratigraphic facies distribution of early Jurassic iron oolite deposits from west central Nevada, USA. Sedimentary Geology, 395, 105537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sedgeo.2019.105537

Collin, P. Y., Loreau, J. P., & Courville, P. (2005). Depositional environments and iron ooid formation in condensed sections (Callovian–Oxfordian, south-eastern Paris basin, France). Sedimentology, 52(5), 969–985. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3091.2005.00728.x

Dahanayake, K., & Krumbein, W. E. (1986). Microbial structures in oolitic iron formations. Mineralium Deposita, 21, 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00204266

Deniel, C., & Pin, C. (2001). Single-stage method for the simultaneous isolation of lead and strontium from silicate samples for isotopic measurements. Analytica Chimica Acta, 426(1), 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-2670(00)01185-5

Dera, G., Brigaud, B., Monna, F., Laffont, R., Pucéat, E., Deconinck, J. F., Pellenard, P., Joachimski, M. M., & Durlet, C. (2011). Climatic ups and downs in a disturbed Jurassic world. Geology, 39(3), 215–218. https://doi.org/10.1130/G31579.1

Dera, G., Prunier, J., Smith, P. L., Haggart, J. W., Popov, E., Guzhov, A., Rogov, M., Delsate, D., Thies, D., Cuny, G., Pucéat, E., Charbonnier, G., & Bayon, G. (2015). Nd isotope constraints on ocean circulation, paleoclimate, and continental drainage during the Jurassic breakup of Pangea. Gondwana Research, 27(4), 1599–1615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2014.02.006

Dera, G., Pucéat, E., Pellenard, P., Neige, P., Delsate, D., Joachimski, M. M., Reisberg, L., & Martinez, M. (2009). Water mass exchange and variations in seawater temperature in the NW Tethys during the Early Jurassic: Evidence from neodymium and oxygen isotopes of fish teeth and belemnites. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 286(1–2), 198–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2009.06.027

Déverin, L. (1945). Etude pétrographique des minerais de fer oolithiques du Dogger des Alpes suisses. In Die Eisen- und Manganerze der Schweiz, Beiträge zur Geologie der Schweiz—Geotechnische Serie, 13/2 (pp. 1–115). Schweizerische Geotechnische Kommission.

Di Bella, M., Sabatino, G., Quartieri, S., Ferretti, A., Cavalazzi, B., Barbieri, R., Foucher, F., Messori, F., & Italiano, F. (2019). Modern iron ooids of hydrothermal origin as a proxy for ancient deposits. Scientific Reports, 9, 7107. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-43181-y

Diebold, P., Bitterli-Brunner, P., & Naef, H. (2005). LK 1049/1069 Frick-Laufenburg. Geological Atlas of Switzerland 1:25 000, Map 110. Wabern: Federal Office of Topography swisstopo.

Diebold, P., Bitterli-Brunner, P., & Naef, H. (2006). LK 1049/1069 Frick-Laufenburg. Geological Atlas of Switzerland 1:25 000, Explanations 110. Wabern: Federal Office of Topography swisstopo.

Dollfus, S. (1961). Über das Alter des Blegi-Ooliths in der Glärnisch-Gruppe. In Mitteilungen der Naturforschenden Gesellschaft des Kantons Glarus, Serie C, Nr. 85 (pp. 91–108).

Dollfus, S. (1965). Über den Helvetischen Dogger zwischen Linth und Rhein. Eclogae Geologicae Helvetiae, 58, 453–554. https://doi.org/10.5169/seals-163277

Donnadieu, Y., Goddéris, Y., Pierrehumbert, R., Dromart, G., Fluteau, F., & Jacob, R. (2006). A GEOCLIM simulation of climatic and biogeochemical consequences of Pangea breakup. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GC001278

Eberli, G.P., Anselmetti, F.S., Isern, A.R., & Delius, H. (2010). Timing of changes in sea-level and currents along Miocene platforms on the Marion Plateau, Australia. In W.A. Morgan, A.D. George, P.M. Harris, J.A. Kupecz, & J.F. Sarg (Eds.), Cenozoic carbonate systems of Australasia (pp. 219–242). Society for Sedimentary Geology, Special Publication, 95. doi: https://doi.org/10.2110/sepmsp.095.219.

El Meknassi, S., Dera, G., Cardone, T., De Rafélis, M., Brahmi, C., & Chavagnac, V. (2018). Sr isotope ratios of modern carbonate shells: Good and bad news for chemostratigraphy. Geology, 46(11), 1003–1006. https://doi.org/10.1130/G45380.1

El Meknassi, S., Dera, G., De Rafélis, M., Brahmi, C., Lartaud, F., Hodel, F., Jeandel, C., Menjot, L., Mounic, S., Henry, M., Besson, P., & Chavagnac, V. (2020). Seawater 87Sr/86Sr ratios along continental margins: Patterns and processes in open and restricted shelf domains. Chemical Geology, 558, 119874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2020.119874

Ellwood, M. J., Hutchins, D. A., Lohan, M. C., Milne, A., Nasemann, P., Nodder, S. D., Sander, S. G., Strzepek, R., Wilhelm, S. W., & Boyd, P. W. (2015). Iron stable isotopes track pelagic iron cycling during a subtropical phytoplankton bloom. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(1), E15–E20. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1421576112

Faure, G., & Mensing, T. M. (2005). Isotopes, principles and applications. Wiley.

Federal Office of Topography swisstopo. (2005). Tectonic map of Switzerland 1:500 000. Wabern: Federal Office of Topography swisstopo.

Föllmi, K. B. (2016). Sedimentary condensation. Earth-Science Reviews, 152, 143–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2015.11.016

Frei, A. (1952). Die Mineralien des Eisenbergwerks Herznach im Lichte morphogenetischer Untersuchungen. In Die Eisen- und Manganerze der Schweiz, Beiträge zur Geologie der Schweiz—Geotechnische Serie, 13/6 (pp. 1–162). Studiengesellschaft für die Nutzbarmachung der schweizerischen Erzlagerstätten & Schweizerische Geotechnische Kommission.

Frey, M., Bucher, K., Frank, E., & Mullis, J. (1980). Alpine metamorphism along the Geotraverse Basel-Chiasso—a review. Eclogae Geologicae Helvetiae, 73, 527–546. https://doi.org/10.5169/seals-164971

Fürsich, F. T. (1979). Genesis, environments, and ecology of Jurassic hardgrounds. Neues Jahrbuch Für Geologie Und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen, 158, 1–63.

Gale, A., Dalton, C. A., Langmuir, C. H., Su, Y., & Schilling, J. G. (2013). The mean composition of ocean ridge basalts. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, 14(3), 489–518. https://doi.org/10.1029/2012GC004334

García-Frank, A., Ureta, S., & Mas, R. (2012). Iron-coated particles from condensed Aalenian-Bajocian deposits: Evolutionary model (Iberian Basin, Spain). Journal of Sedimentary Research, 82(12), 953–968. https://doi.org/10.2110/jsr.2012.75

Garçon, M. (2021). Episodic growth of felsic continents in the past 3.7 Ga. Science Advances. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abj1807

Gehring, A. U. (1985). A microchemical study of iron ooids. Eclogae Geologicae Helvetiae, 78(3), 451–457. https://doi.org/10.5169/seals-165664

Gehring, A. U. (1986a). Mikroorganismen in kondensierten Schichten der Dogger/Malm-Wende im Jura der Nordostschweiz. Eclogae Geologicae Helvetiae, 79(1), 13–18. https://doi.org/10.5169/seals-165822

Gehring, A. U. (1986b). Untersuchungen zur Bildung von Eisenoolithen. Mitteilungen aus dem Geologischen Institut der Eidg. Techn. Hochschule und der Universität Zürich, Ph.D. Thesis, 261, 1–114. doi: https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-a-000412585.

Gehring, A. U. (1989). The formation of goethitic ooids in condensed Jurassic deposits in northern Switzerland. In T.P. Young, & W.E.G. Taylor (Eds.), Phanerozoic Ironstones (pp. 133–139). Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 46(1). doi: https://doi.org/10.1144/GSL.SP.1989.046.01.13.

Gehring, A. U., & Heller, F. (1989). Timing of natural remanent magnetization in ferriferous limestones from the Swiss Jura mountains. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 93(2), 261–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/0012-821X(89)90074-5

Gisler, C., Labhart, T., Spillmann, P., Herwegh, M., Della Valle, G., Trüssel, M., & Wiederkehr, M. (2020). LK 1210 Innertkirchen. Geological Atlas of Switzerland 1:25 000, Explanations 167. Wabern: Federal Office of Topography swisstopo.

Gisler, C., & Spillmann, P. (2011). Die mesozoisch-alttertiäre Sedimentbedeckung. In P. Spillmann (Ed.), Geologie des Kantons Uri (pp. 49–78). Naturforschende Gesellschaft Uri, 24.

Glasauer, S., Mattes, A., & Gehring, A. U. (2013). Constraints on the preservation of ferriferous microfossils. Geomicrobiology Journal, 30(6), 479–489. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490451.2012.718408

Gómez, J. J., & Fernández-López, S. (1994). Condensation processes in shallow platforms. Sedimentary Geology, 92(3–4), 147–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/0037-0738(94)90103-1

Gradstein, F. M., Ogg, J. G., Schmitz, M. B., & Ogg, G. M. (2012). The geologic time scale 2012. Elsevier.

Gradstein, F. M., Ogg, J. G., Schmitz, M. D., & Ogg, G. M. (2020). Geologic time scale 2020. Elsevier.

Gygi, R. A. (1981). Oolitic iron formations: Marine or not marine? Eclogae Geologicae Helvetiae, 74(1), 233–254. https://doi.org/10.5169/seals-165102

Gygi, R. A. (2000). Integrated stratigraphy of the Oxfordian and Kimmeridgian (Late Jurassic) in northern Switzerland and adjacent southern Germany. Birkhäuser Verlag.

Gygi, R. A., & Marchand, D. (1982). Les faunes de Cardioceratinae (Ammonoidea) du Callovien terminal et de l’Oxfordien inférieur et moyen (Jurassique) de la Suisse septentrionale: Stratigraphie, paléoécologie, taxonomie préliminaire. Geobios, 15(4), 517–571. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-6995(82)80072-7

Halliday, A. N., & Mitchell, J. G. (1984). K-Ar ages of clay-size concentrates from the mineralisation of the Pedroches Batholith, Spain, and evidence for Mesozoic hydrothermal activity associated with the break up of Pangaea. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 68(2), 229–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/0012-821X(84)90155-9

Hänni, R. (1999). Der geologische Bau des Helvetikums im Berner Oberland. Bern, Switzerland, University of Bern, Ph.D. Thesis, 148pp.

Hantke, R., Brückner, W., Oberhänsli, R., Schenker, F., Haldimann, P., & Schreurs, G. (2011). LK 1192 Schächental. Geological Atlas of Switzerland 1:25 000, Explanations 83. Wabern: Federal Office of Topography swisstopo.

Harder, H. (1978). Synthesis of iron layer silicate minerals under natural conditions. Clays and Clay Minerals, 26, 65–72. https://doi.org/10.1346/CCMN.1978.0260108

Heezen, B. C., & Hollister, C. (1964). Deep-sea current evidence from abyssal sediments. Marine Geology, 1(2), 141–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/0025-3227(64)90012-X

Heikoop, J. M., Tsujita, C. J., Risk, M. J., Tomascik, T., & Mah, A. J. (1996). Modern iron ooids from a shallow-marine volcanic setting: Mahengetang, Indonesia. Geology, 24(8), 759–762. https://doi.org/10.1130/0091-7613(1996)024%3c0759:MIOFAS%3e2.3.CO;2

Heim, A. (1878). Untersuchungen über den Mechanismus der Gebirgsbildung im Anschluss an die geologische Monographie der Tödi-Windgällen-Gruppe. Schwabe.

Herwegh, M., Berger, A., Baumberger, R., Wehrens, P., & Kissling, E. (2017). Large-scale crustal-block-extrusion during late Alpine collision. Scientific Reports, 7, 413. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-00440-0

Hodell, D. A., Mead, G. A., & Mueller, P. A. (1990). Variation in the strontium isotopic composition of seawater (8 Ma to present): Implications for chemical weathering rates and dissolved fluxes to the oceans. Chemical Geology: Isotope Geoscience Section, 80(4), 291–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-9622(90)90011-Z

Holz, M. (2015). Mesozoic paleogeography and paleoclimates—A discussion of the diverse greenhouse and hothouse conditions of an alien world. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 61, 91–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsames.2015.01.001

Hradetzky, H., & Lippolt, H. J. (1993). Generation and distortion of Rb/Sr whole-rock isochrones—effects of metamorphism and alteration. European Journal of Mineralogy, 5(6), 1175–1194. https://doi.org/10.1127/ejm/5/6/1175

Huang, H., Gutjahr, M., Kuhn, G., Hathorne, E. C., & Eisenhauer, A. (2021). Efficient extraction of past seawater Pb and Nd isotope signatures from Southern Ocean sediments. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GC009287

Huang, K.-F., You, C.-F., Chung, C.-H., & Lin, I.-T. (2011). Nonhomogeneous seawater Sr isotopic composition in the coastal oceans: A novel tool for tracing water masses and submarine groundwater discharge. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. https://doi.org/10.1029/2010GC003372

Huon, S., Burkhard, M., & Hunziker, J.-C. (1994). Mineralogical, K-Ar, stable and Sr isotope systematics of K-white micas during very low-grade metamorphism of limestones (Helvetic nappes, western Switzerland). Chemical Geology, 113(3–4), 347–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-2541(94)90075-2

Ingram, B., & Sloan, D. (1992). Strontium isotopic composition of estuarine sediments as paleosalinity-paleoclimate indicator. Science, 255(5040), 68–72. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.255.5040.68

Jacobsen, S. B., & Wasserburg, G. J. (1980). Sm-Nd isotopic evolution of chondrites. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 50(1), 139–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/0012-821X(80)90125-9

Jeannet, A. (1951). Stratigraphie und Palaeontologie des oolithischen Eisenerzlagers von Herznach und seiner Umgebung. In Die Eisen- und Manganerze der Schweiz, Beiträge zur Geologie der Schweiz—Geotechnische Serie, 13/5 (pp. 1–240). Studiengesellschaft für die Nutzbarmachung der schweizerischen Erzlagerstätten & Schweizerische Geotechnische Kommission.

Jenkin, G. R. T., Ellam, R. M., Rogers, G., & Stuart, F. M. (2001). An investigation of closure temperature of the biotite Rb-Sr system: The importance of cation exchange. Geochimica Et Cosmochimica Acta, 65(7), 1141–1160. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7037(00)00560-3

Jenkyns, H. C. (1971). The genesis of condensed sequences in the Tethyan Jurassic. Lethaia, 4(3), 327–352. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1502-3931.1971.tb01928.x

Kennedy, C. B., Scott, S. D., & Ferris, F. G. (2003). Characterization of bacteriogenic iron oxide deposits from Axial Volcano, Juan de Fuca Ridge, northeast Pacific Ocean. Geomicrobiology Journal, 20(3), 199–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490450303873

Kennedy, M. J., Pevear, D. R., & Hill, R. J. (2002). Mineral surface control of organic carbon in black shale. Science, 295(5555), 657–660. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1066611

Kirschner, D. L., Masson, H., & Cosca, M. A. (2003). An 40Ar/39Ar, Rb/Sr, and stable isotope study of micas in low-grade fold-and-thrust belt: An example from the Swiss Helvetic Alps. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 145, 460–480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00410-003-0461-2

Kirschner, D. L., Masson, H., & Sharp, Z. D. (1999). Fluid migration through thrust faults in the Helvetic nappes (Western Swiss Alps). Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 136, 169–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004100050530

Kraemer, S. M. (2004). Iron oxide dissolution and solubility in the presence of siderophores. Aquatic Sciences, 66(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00027-003-0690-5

Kugler, C. (1987). Die Wildegg-Formation im Ostjura und die Schilt-Formation im östlichen Helvetikum—ein Vergleich. Mitteilungen aus dem Geologischen Institut der Eidg. Techn. Hochschule und der Universität Zürich, Ph.D. Thesis, vol. 259, pp. 1–209.

Lalonde, K., Mucci, A., Ouellet, A., & Gélinas, Y. (2012). Preservation of organic matter in sediments promoted by iron. Nature, 483, 198–200. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10855

Lewis, K. B. (1973). Erosion and deposition on a tilting continental shelf during Quaternary oscillations of sea level. New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics, 16(2), 281–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/00288306.1973.10431458

Li, F., Zhang, P., Ma, X., & Yuan, G. (2021). The iron oolitic deposits of the lower Devonian Yangmaba formation in the Longmenshan area, Sichuan Basin. Marine and Petroleum Geology, 130, 105137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2021.105137

Looser, N., Guillong, M., Laurent, O., Rickli, J., Fernandez, A., & Bernasconi, S.M. (2019). Constraining the Multi-Stage Burial and Tectonic History of Northern Switzerland over the Last 200 Ma with Carbonate Clumped Isotopes and LA-ICP-MS U-Pb Dating. Goldschmidt Abstracts, p. 2047.

Lucchi, F. (2009). Late-Quaternary terraced marine deposits as tools for wide-scale correlation of unconformity-bounded units in the volcanic Aeolian archipelago (southern Italy). Sedimentary Geology, 216(3–4), 158–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sedgeo.2009.03.003

Lucchi, F., Tranne, C. A., Calanchi, N., & Rossi, P. L. (2007). Late Quaternary deformation history of the volcanic edifice of Panarea, Aeolian Arc, Italy. Bulletin of Volcanology, 69, 239–257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00445-006-0070-9

Martire, L. (1992). Sequence stratigraphy and condensed pelagic sediments. An example from the Rosso Ammonitico Veronese, northeastern Italy. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 94(1–4), 169–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-0182(92)90118-O

Martire, L. (1996). Stratigraphy, facies and synsedimentary tectonics in the Jurassic Rosso Ammonitico Veronese (Altopiano di Asiago, NE Italy). Facies, 35, 209–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02536963

Mazurek, M., Hurford, A. J., & Leu, W. (2006). Unravelling the multi-stage burial history of the Swiss Molasse Basin: Integration of apatite fission track, vitrinite reflectance and biomarker isomerisation analysis. Basin Research, 18(1), 27–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2117.2006.00286.x

Miron, G. D., Wagner, T., Wälle, M., & Heinrich, C. A. (2013). Major and trace-element composition and pressure–temperature evolution of rock-buffered fluids in low-grade accretionary-wedge metasediments, Central Alps. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 165, 981–1008. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00410-012-0844-3

Mullis, J., Dubessy, J., Poty, B., & O’Neil, J. (1994). Fluid regimes during late stages of a continental collision: Physical, chemical, and stable isotope measurements of fluid inclusions in fissure quartz from a geotraverse through the Central Alps, Switzerland. Geochimica Et Cosmochimica Acta, 58(10), 2239–2267. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(94)90008-6

Norris, M. S., & Hallam, A. (1995). Facies variations across the Middle-Upper Jurassic boundary in Western Europe and the relationship to sea-level changes. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 116(3–4), 189–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-0182(94)00096-Q

Oades, J. M. (1988). The retention of organic matter in soils. Biogeochemistry, 5, 35–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02180317

Olivier, N., & Boyet, M. (2006). Rare earth and trace elements of microbialites in Upper Jurassic coral- and sponge-microbialite reefs. Chemical Geology, 230(1–2), 105–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2005.12.002

Paulay, G., & McEdward, L. R. (1990). A simulation model of island reef morphology: The effects of sea level fluctuations, growth, subsidence and erosion. Coral Reefs, 9, 51–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00368800

Paytan, A., Griffith, E. M., Eisenhauer, A., Hain, M. P., Wallmann, K., & Ridgwell, A. (2021). A 35-million-year record of seawater stable Sr isotopes reveals a fluctuating global carbon cycle. Science, 371(6536), 1346–1350. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaz9266

Pearce, C. R., Parkinson, I. J., Gaillardet, J., Charlier, B. L., Mokadem, F., & Burton, K. W. (2015). Reassessing the stable (δ88/86Sr) and radiogenic (87Sr/86Sr) strontium isotopic composition of marine inputs. Geochimica Et Cosmochimica Acta, 157, 125–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2015.02.029

Pin, C., & Zalduegui, J. S. (1997). Sequential separation of light rare-earth elements, thorium and uranium by miniaturized extraction chromatography: Application to isotopic analyses of silicate rocks. Analytica Chimica Acta, 339(1–2), 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-2670(96)00499-0

Préat, A., de Jong, J. T., Mamet, B. L., & Mattielli, N. (2008). Stable iron isotopes and microbial mediation in red pigmentation of the Rosso Ammonitico (Mid-Late Jurassic, Verona area, Italy). Astrobiology, 8(4), 841–857. https://doi.org/10.1089/ast.2006.0035

Préat, A., Morano, S., Loreau, J. P., Durlet, C., & Mamet, B. (2006). Petrography and biosedimentology of the Rosso Ammonitico Veronese (middle-upper Jurassic, north-eastern Italy). Facies, 52, 265–278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10347-005-0032-2

Rais, P., Louis-Schmid, B., Bernasconi, S. M., & Weissert, H. (2007). Palaeoceanographic and palaeoclimatic reorganization around the Middle-Late Jurassic transition. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 251(3–4), 527–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.05.008

Raiswell, R., & Canfield, D. E. (2012). The iron biogeochemical cycle past and present. Geochemical Perspectives, 1(1), 1–220.

Reineck, H. E., & Singh, I. B. (2012). Depositional sedimentary environments: With reference to terrigenous clastics (2nd ed.). Springer-Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-81498-3

Rickli, J., Frank, M., Stichel, T., Georg, R. B., Vance, D., & Halliday, A. N. (2013). Controls on the incongruent release of hafnium during weathering of metamorphic and sedimentary catchments. Geochimica Et Cosmochimica Acta, 101, 263–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2012.10.019

Röthlisberger, C. (1990). Geologie der Windgällenfalte und der Hoch Faulendecke in der Region Brunni—Gross Ruchen, Kanton Uri. Zurich, Switzerland, ETH Zurich, Diploma Thesis, unpublished, 192pp.

Rudnick, R., & Gao, S. (2003). Composition of the continental crust. In H. D. Holland & K. K. Turekian (Eds.), Treatise on geochemistry (Vol. 3, pp. 1–64). Elsevier.

Salama, W., El Aref, M. M., & Gaupp, R. (2013). Mineral evolution and processes of ferruginous microbialite accretion—an example from the Middle Eocene stromatolitic and ooidal ironstones of the Bahariya Depression, Western Desert. Egypt. Geobiology, 11(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/gbi.12011

Schaltegger, U., Stille, P., Rais, N., Piqué, A., & Clauer, N. (1994). Neodymium and strontium isotopic dating of diagenesis and low-grade metamorphism of argillaceous sediments. Geochimica Et Cosmochimica Acta, 58(5), 1471–1481. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(94)90550-9

Schenker, F. (1980). Geologische und mineralogische Untersuchungen im Gebiet der Kleinen und Grossen Windgälle, Maderanertal, Kt. Uri. Bern, Switzerland, University of Bern, Diploma Thesis, unpublished, 100pp.

Schenker, F. (1986). Spätpaläozoischer saurer Magmatismus und Beckenbildung im Aarmassiv unter kompressiver Tektonik. Bern, Switzerland, University of Bern, Inauguraldissertation, 116pp.

Scotese, C. R., & Schettino, A. (2017). Late Permian-Early Jurassic paleogeography of western Tethys and the world. In J. I. Soto, J. F. Flinch, & G. Tari (Eds.), Permo-Triassic salt provinces of Europe, North Africa and the Atlantic margins (pp. 57–95). Amsterdam: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-809417-4.00004-5

Scotese, C. R. (1991). Jurassic and Cretaceous plate tectonic reconstructions. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 87(1–4), 493–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-0182(91)90145-H

Siehl, A., & Thein, J. (1989). Minette-type ironstones. In T.P. Young, & W.E.G. Taylor (Eds.), Phanerozoic ironstones (vol. 46(1), pp. 175–193). Geological Society, London, Special Publications. doi: https://doi.org/10.1144/GSL.SP.1989.046.01.16.

Staeger, D., Labhart, T., Della Valle, G., Tröhler, B., Schwarz, H., Gisler, C., Rathmayr, B., & Wiederkehr, M. (2020). LK 1210 Innertkirchen. Geological Atlas of Switzerland 1:25 000, Map 167. Wabern: Federal Office of Topography swisstopo.

Stille, P., & Fischer, H. (1990). Secular variation in the isotopic composition of Nd in Tethys seawater. Geochimica Et Cosmochimica Acta, 54(11), 3139–3145. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(90)90129-9

Sturesson, U., Heikoop, J. M., & Risk, M. J. (2000). Modern and Palaeozoic iron ooids—a similar volcanic origin. Sedimentary Geology, 136(1–2), 137–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0037-0738(00)00091-9

Sun, M., Archer, C., & Vance, D. (2021). New methods for the chemical isolation and stable isotope measurement of multiple transition metals, with application to the earth sciences. Geostandards and Geoanalytical Research, 45(4), 643–658. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggr.12402

Swift, D.J.P., & Thorne, J.A. (1991). Sedimentation on continental margins, I: a general model for shelf sedimentation. In D.J.P. Swift, G.F. Oertel, R.W. Tillman, & J.A. Thorne (Eds.), Shelf sand and sandstone bodies: Geometry, facies and sequence stratigraphy (pp. 3–31). International Association of Sedimentologists, Oxford, Special Publications, 14.

Tan, B. K. (1976). Oolite deformation in Windgällen, Canton Uri, Switzerland. Tectonophysics, 31(3–4), 157–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-1951(76)90117-7

Thirlwall, M. F. (1991). Long-term reproducibility of multicollector Sr and Nd isotope ratio analysis. Chemical Geology: Isotope Geoscience Section, 94(2), 85–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-9622(91)90002-E

Tröhler, B. (1966). Geologie der Glockhaus-Gruppe: mit besonderer Berücksichtigung des Eisenoolithes der Erzegg-Planplatte. In Die Eisen- und Manganerze der Schweiz, Beiträge zur Geologie der Schweiz—Geotechnische Serie, 13/10 (pp. 1–137). Schweizerische Geotechnische Kommission.

Trümpy, R. (1949). Der Lias der Glarner Alpen. Zurich, Switzerland, ETH Zurich, Ph.D. Thesis, 192pp.

Trümpy, R. (1952). Der Nordrand der Liasischen Tethys in den Schweizer Alpen. Geologische Rundschau, 40, 239–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01803435

Van Hinsbergen, D. J., Torsvik, T. H., Schmid, S. M., Matenco, L. C., Maffione, M., Vissers, R. L., Gürer, D., & Spakman, W. (2020). Orogenic architecture of the Mediterranean region and kinematic reconstruction of its tectonic evolution since the Triassic. Gondwana Research, 81, 79–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2019.07.009

Vance, D., Little, S. H., Archer, C., Cameron, V., Andersen, M. B., Rijkenberg, M. J., & Lyons, T. W. (2016). The oceanic budgets of nickel and zinc isotopes: The importance of sulfidic environments as illustrated by the Black Sea. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society a: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 374(2081), 20150294. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2015.0294

Vance, D., & Thirlwall, M. (2002). An assessment of mass discrimination in MC-ICPMS using Nd isotopes. Chemical Geology, 185(3–4), 227–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0009-2541(01)00402-8

Wierzbowski, H., Anczkiewicz, R., Pawlak, J., Rogov, M. A., & Kuznetsov, A. B. (2017). Revised Middle-Upper Jurassic strontium isotope stratigraphy. Chemical Geology, 466, 239–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2017.06.015

Wohlwend, S., Bläsi, H.R., Feist-Burkhardt, S., Hostettler, B., Menkveld-Gfeller, U., Dietze, V., & Deplazes, G. (2022): TBO Bözberg-2–1: Data Report—Dossier IV: Microfacies, Bio- and Chemostratigraphic Analysis. Nagra Arbeitsbericht NAB 21–22. Wettingen: National Cooperative for the Disposal of Radioactive Waste, Nagra.

Worsfold, P. J., Lohan, M. C., Ussher, S. J., & Bowie, A. R. (2014). Determination of dissolved iron in seawater: A historical review. Marine Chemistry, 166, 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marchem.2014.08.009

Ziegler, P. A. (1993). Late Palaeozoic-Early Mesozoic plate reorganization: Evolution and demise of the Variscan Fold Belt. In J. F. von Raumer & F. Neubauer (Eds.), Pre-Mesozoic geology in the Alps (pp. 203–216). Springer.

Ziegler, P. A. (1988). Evolution of the Arctic-North Atlantic and the Western Tethys. American Association of Petroleum Geologists Memoirs, 43, 198.

Acknowledgements

SS would like to express his gratitude to Franz Schenker and Eric Reusser for arousing interest in this topic and for fruitful discussions. Corey Archer and Iván Hernández are thanked for analytical support in the laboratory. I thank Christian Gisler and Michael Wiederkehr for providing the stratigraphic profile of the Aar Massif. We would also like to acknowledge Sébastien Fabre and Josef Michalik for their critical and constructive reviews.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zürich.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SS, DV, HW, and SW conducted the field work and collected the samples. SS, JR, DV, and SW carried out the analyses. All authors discussed and interpreted the data. SS drafted the initial manuscript, all co-authors provided editorial support. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Editorial handling: Wilfried Winkler

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schunck, S., Rickli, J., Wohlwend, S. et al. Continental weathering as the source of iron in Jurassic iron oolites from Switzerland. Swiss J Geosci 116, 4 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s00015-023-00431-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s00015-023-00431-6