Abstract

The ability to generate novel ideas, known as divergent thinking, depends on both semantic knowledge and episodic memory. Semantic knowledge and episodic memory are known to interact to support memory decisions, but how they may interact to support divergent thinking is unknown. Moreover, it is debated whether divergent thinking relies on spontaneous or controlled retrieval processes. We addressed these questions by examining whether divergent thinking ability relates to interactions between semantic knowledge and different episodic memory processes. Participants completed the alternate uses task of divergent thinking, and completed a memory task in which they searched for target objects in schema-congruent or schema-incongruent locations within scenes. In a subsequent test, participants indicated where in each scene the target object had been located previously (i.e., spatial accuracy test), and provided confidence-based recognition memory judgments that indexed distinct episodic memory processes (i.e., recollection, familiarity, and unconscious memory) for the scenes. We found that higher divergent thinking ability—specifically in terms of the number of ideas generated—was related to (1) more of a benefit from recollection (a controlled process) and unconscious memory (a spontaneous process) on spatial accuracy and (2) beneficial differences in how semantic knowledge was combined with recollection and unconscious memory to influence spatial accuracy. In contrast, there were no effects with respect to familiarity (a spontaneous process). These findings indicate that divergent thinking is related to both controlled and spontaneous memory processes, and suggest that divergent thinking is related to the ability to flexibly combine semantic knowledge with episodic memory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The experiment was not preregistered. The data and code are available upon request.

Notes

The extent to which unconscious memory is its own process, or simply an expression of other types of memory (e.g., familiarity) below a threshold of subjective awareness is a subject of debate, and the present treatment is agnostic as to what type of representations or systems might underpin unconscious memory.

By convention, a BF10 < 0.33 indicates substantial evidence for the null hypothesis, and a BF10 < 0.01 indicates extreme evidence for the null (Jeffreys, 1961).

References

Addis, D. R., Pan, L., Musicaro, R., & Schacter, D. L. (2016). Divergent thinking and constructing episodic simulations. Memory, 24(1), 89–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2014.985591

Andreasen, N. C. (2011). A journey into chaos: Creativity and the unconscious. Mens Sana Monographs, 9(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-1229.77424

Bastin, C., Besson, G., Simon, J., Delhaye, E., Geurten, M., Willems, S., & Salmon, E. (2019). An integrative memory model of recollection and familiarity to understand memory deficits. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 42. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X19000621

Beaty, R. E., Silvia, P. J., Nusbaum, E. C., Jauk, E., & Benedek, M. (2014). The roles of associative and executive processes in creative cognition. Memory & Cognition, 42(7), 1186–1197. https://doi.org/10.3758/S13421-014-0428-8

Beaty, R. E., Thakral, P. P., Madore, K. P., Benedek, M., & Schacter, D. L. (2018). Core network contributions to remembering the past, imagining the future, and thinking creatively. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 30(12), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1162/JOCN_A_01327

Beaty, R. E., Chen, Q., Christensen, A. P., Kenett, Y. N., Silvia, P. J., Benedek, M., & Schacter, D. L. (2020). Default network contributions to episodic and semantic processing during divergent creative thinking: A representational similarity analysis. NeuroImage, 209, 116499. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2019.116499

Benedek, M., & Jauk, E. (2018). Spontaneous and controlled processes. In K. C. R. Fox & K. Christoff (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of spontaneous thought: Mind-wandering, creativity, and dreaming (pp. 285–298). Oxford University Press.

Benedek, M., Jauk, E., Fink, A., Koschutnig, K., Reishofer, G., Ebner, F., & Neubauer, A. C. (2014). To create or to recall? Neural mechanisms underlying the generation of creative new ideas. NeuroImage, 88, 125–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2013.11.021

Benedek, M., Jauk, E., Sommer, M., Arendasy, M., & Neubauer, A. C. (2014). Intelligence, creativity, and cognitive control: The common and differential involvement of executive functions in intelligence and creativity. Intelligence, 46(1), 73–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.INTELL.2014.05.007

Benedek, M., Kenett, Y. N., Umdasch, K., Anaki, D., Faust, M., & Neubauer, A. C. (2017). How semantic memory structure and intelligence contribute to creative thought: A network science approach. Thinking and Reasoning, 23(2), 158–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/13546783.2016.1278034

Benedek, M., Beaty, R. E., Schacter, D. L., & Kenett, Y. N. (2023). The role of memory in creative ideation. Nature Reviews Psychology, 2(4), 246–257. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-023-00158-z

Boettcher, S. E. P., Draschkow, D., Dienhart, E., & Võ, M.L.-H. (2018). Anchoring visual search in scenes: Assessing the role of anchor objects on eye movements during visual search. Journal of Vision, 18(13), 11. https://doi.org/10.1167/18.13.11

Carson, S. H., Peterson, J. B., & Higgins, D. M. (2005). Reliability, validity, and factor structure of the creative achievement questionnaire. Creativity Research Journal, 17(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326934CRJ1701_4

Condon, D. M., & Revelle, W. (2014). The international cognitive ability resource: Development and initial validation of a public-domain measure. Intelligence, 43(1), 52–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.INTELL.2014.01.004

de Leeuw, J. R. (2015). jsPsych: A JavaScript library for creating behavioral experiments in a web browser. Behavior Research Methods, 47(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-014-0458-y

Dewhurst, S. A., Thorley, C., Hammond, E. R., & Ormerod, T. C. (2011). Convergent, but not divergent, thinking predicts susceptibility to associative memory illusions. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(1), 73–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PAID.2011.03.018

Eichenbaum, H., Yonelinas, A. P., & Ranganath, C. (2007). The medial temporal lobe and recognition memory. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 30, 123–152. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094328

Ellamil, M., Dobson, C., Beeman, M., & Christoff, K. (2012). Evaluative and generative modes of thought during the creative process. NeuroImage, 59(2), 1783–1794. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2011.08.008

Frith, E., Kane, M. J., Welhaf, M. S., Christensen, A. P., Silvia, P. J., & Beaty, R. E. (2021). Kee** creativity under control: Contributions of attention control and fluid intelligence to divergent thinking. Creativity Research Journal, 33(2), 138–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2020.1855906

George, T., & Wiley, J. (2019). Fixation, flexibility, and forgetting during alternate uses tasks. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 13(3), 305–313. https://doi.org/10.1037/ACA0000173

Ghosh, V. E., & Gilboa, A. (2014). What is a memory schema? A historical perspective on current neuroscience literature. Neuropsychologia, 53(1), 104–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2013.11.010

Gilboa, A., & Marlatte, H. (2017). Neurobiology of schemas and schema-mediated memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 21(8), 618–631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2017.04.013

Gilhooly, K., Fioratou, E., Anthony, S., & Wynn, V. (2007). Divergent thinking: Strategies and executive involvement in generating novel uses for familiar objects. British Journal of Psychology, 98(4), 611–625. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317907X173421

Greve, A., Cooper, E., Tibon, R., & Henson, R. N. (2019). Knowledge is power: Prior knowledge aids memory for both congruent and incongruent events, but in different ways. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 148(2), 325–341. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000498

Guilford, J. P. (1967). Creativity: Yesterday, today and tomorrow. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 1(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/J.2162-6057.1967.TB00002.X

Hannula, D. E., & Greene, A. J. (2012). The hippocampus reevaluated in unconscious learning and memory: At a tip** point? Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6, 80. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2012.00080

Hannula, D. E., & Ranganath, C. (2009). The eyes have it: hippocampal activity predicts expression of memory in eye movements. Neuron, 63(5), 592–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2009.08.025

He, L., Kenett, Y. N., Zhuang, K., Liu, C., Zeng, R., Yan, T., Huo, T., & Qiu, J. (2020). The relation between semantic memory structure, associative abilities, and verbal and figural creativity. Thinking and Reasoning, 27(2), 268–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/13546783.2020.1819415

Hemmer, P., & Steyvers, M. (2009). A Bayesian account of reconstructive memory. Topics in Cognitive Science, 1(1), 189–202. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-8765.2008.01010.x

Huba, G. J., Singer, J. L., Aneshensel, C. S., & Antrobus, J. S. (1982). The short imaginal processes inventory. Research Psychologist Press.

Huttenlocher, J., Hedges, L. V., & Duncan, S. (1991). Categories and particulars: Prototype effects in estimating spatial location. Psychological Review, 98(3), 352–376. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.98.3.352

Huttenlocher, J., Hedges, L. V., & Vevea, J. L. (2000). Why do categories affect stimulus judgment? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 129(2), 220–241. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.129.2.220

Irish, M. (2016). Semantic memory as the essential scaffold for future-oriented mental time travel. In K. Michaelian, S. B. Klein, & K. K. Szpunar (Eds.), Seeing the future: Theoretical perspectives on future-oriented mental time travel (pp. 389–408). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190241537.003.0019

Irish, M. (2020). On the interaction between episodic and semantic representations–constructing a unified account of imagination. In A. Abraham (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of the imagination (pp. 447–465). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108580298.027

Jacoby, L. L., & Kelley, C. (1992). Unconscious influences of memory: Dissociations and automaticity. In A. D. Milner & M. D. Rugg (Eds.), The neuropsychology of consciousness (pp. 201–233). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-498045-7.50015-3

Jeffreys, H. (1961). Theory of probability (3rd ed.). Clarendon.

Kenett, Y. N. (2018). Investigating creativity from a semantic network perspective. In Z. Kapoula, E. Volle, J. Renoult, & M. Andreatta (Eds.), Exploring transdisciplinarity in art and sciences (pp. 49–75). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-76054-4_3

Kenett, Y. N., Anaki, D., & Faust, M. (2014). Investigating the structure of semantic networks in low and high creative persons. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 407. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00407

Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B., & Christensen, R. H. B. (2017). lmerTest Package: Tests in Linear Mixed Effects Models. Journal of Statistical Software, 82(13), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v082.i13

Lampinen, J. M., Faries, J. M., Neuschatz, J. S., & Toglia, M. P. (2000). Recollections of Things Schematic: The Influence of Scripts on Recollective Experience. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 14(6), 543–554. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-0720(200011/12)14:6%3c543::AID-ACP674%3e3.0.CO;2-K

Lampinen, J. M., Copeland, S. M., & Neuschatz, J. S. (2001). Recollections of things schematic: Room schemas revisited. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning Memory and Cognition, 27(5), 1211–1222. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.27.5.1211

Lee, C. S., & Therriault, D. J. (2013). The cognitive underpinnings of creative thought: A latent variable analysis exploring the roles of intelligence and working memory in three creative thinking processes. Intelligence, 41(5), 306–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.INTELL.2013.04.008

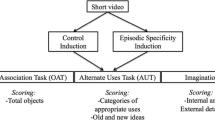

Madore, K. P., Addis, D. R., & Schacter, D. L. (2015). Creativity and memory: Effects of an episodic-specificity induction on divergent thinking. Psychological Science, 26(9), 1461–1468. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615591863

Madore, K. P., **g, H. G., & Schacter, D. L. (2016). Divergent creative thinking in young and older adults: Extending the effects of an episodic specificity induction. Memory & Cognition, 44(6), 974–988. https://doi.org/10.3758/S13421-016-0605-Z

Madore, K. P., Thakral, P. P., Beaty, R. E., Addis, D. R., & Schacter, D. L. (2019). Neural mechanisms of episodic retrieval support divergent creative thinking. Cerebral Cortex, 29(1), 150–166. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhx312

Mednick, S. (1962). The associative basis of the creative process. Psychological Review, 69(3), 220–232. https://doi.org/10.1037/H0048850

Miroshnik, K. G., Forthmann, B., Karwowski, M., & Benedek, M. (2023). The relationship of divergent thinking with broad retrieval ability and processing speed: A meta-analysis. Intelligence, 98, 101739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2023.101739

Nusbaum, E. C., & Silvia, P. J. (2011). Are intelligence and creativity really so different?. Fluid intelligence, executive processes, and strategy use in divergent thinking. Intelligence, 39(1), 36–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.INTELL.2010.11.002

Palmiero, M., Fusi, G., Crepaldi, M., Borsa, V. M., & Rusconi, M. L. (2022). Divergent thinking and the core executive functions: a state-of-the-art review. Cognitive Processing, 23(3), 341–366. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10339-022-01091-4

Persaud, K., Macias, C., Hemmer, P., & Bonawitz, E. (2021). Evaluating recall error in preschoolers: Category expectations influence episodic memory for color. Cognitive Psychology, 124, 101357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogpsych.2020.101357

Poincaré, H. (1914). Science and method. Dover.

Ramey, M. M., Yonelinas, A. P., & Henderson, J. M. (2019). Conscious and unconscious memory differentially impact attention: Eye movements, visual search, and recognition processes. Cognition, 185, 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COGNITION.2019.01.007

Ramey, M. M., Henderson, J. M., & Yonelinas, A. P. (2020). The spatial distribution of attention predicts familiarity strength during encoding and retrieval. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 149(11), 2046–2062. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000758

Ramey, M. M., Yonelinas, A. P., & Henderson, J. M. (2020). Why do we retrace our visual steps? Semantic and episodic memory in gaze reinstatement. Learning and Memory, 27(7), 275–283. https://doi.org/10.1101/lm.051227.119

Ramey, M. M., Henderson, J. M., & Yonelinas, A. P. (2022a). Eye movements dissociate between perceiving, sensing, and unconscious change detection in scenes. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 29(6), 2122–2132. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-022-02122-z

Ramey, M. M., Henderson, J. M., & Yonelinas, A. P. (2022b). Episodic memory processes modulate how schema knowledge is used in spatial memory decisions. Cognition, 225, 105111. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COGNITION.2022.105111

Renoult, L., Irish, M., Moscovitch, M., & Rugg, M. D. (2019). From knowing to remembering: The semantic-episodic distinction. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 23(12), 1041–1057. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TICS.2019.09.008

Ritter, S. M., & Dijksterhuis, A. (2014). Creativity-the unconscious foundations of the incubation period. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 215. https://doi.org/10.3389/FNHUM.2014.00215/BIBTEX

Ritter, S. M., van Baaren, R. B., & Dijksterhuis, A. (2012). Creativity: The role of unconscious processes in idea generation and idea selection. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 7(1), 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TSC.2011.12.002

Rosenthal, R., & Rosnow, R. L. (1991). Essentials of behavioral research: Methods and data analysis. McGraw-Hill.

Ryan, J. D., Althoff, R. R., Whitlow, S., & Cohen, N. J. (2000). Amnesia is a deficit in relational memory. Psychological Science, 11(6), 454–461. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00288

Seli, P., Risko, E. F., & Smilek, D. (2016). Assessing the associations among trait and state levels of deliberate and spontaneous mind wandering. Consciousness and Cognition, 41, 50–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CONCOG.2016.02.002

Silvia, P. J., Beaty, R. E., & Nusbaum, E. C. (2013). Verbal fluency and creativity: General and specific contributions of broad retrieval ability (Gr) factors to divergent thinking. Intelligence, 41(5), 328–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.INTELL.2013.05.004

Smith, S. M., Ward, T. B., & Schumacher, J. S. (1993). Constraining effects of examples in a creative generation task. Memory & Cognition, 21(6), 837–845. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03202751/METRICS

Squire, L. R., Wixted, J. T., & Clark, R. E. (2007). Recognition memory and the medial temporal lobe: A new perspective. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 8(11), 872. https://doi.org/10.1038/NRN2154

Sternberg, R. J., & Lubart, T. I. (1999). The concept of creativity: Prospects and parad. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of creativity (pp. 3–15). Cambridge University Press https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1998-08125-001

Sweegers, C. C. G., Coleman, G. A., van Poppel, E. A. M., Cox, R., & Talamini, L. M. (2015). Mental schemas hamper memory storage of goal-irrelevant information. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 9, 629. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2015.00629

Takeuchi, H., Taki, Y., Hashizume, H., Sassa, Y., Nagase, T., Nouchi, R., & Kawashima, R. (2011). Failing to deactivate: The association between brain activity during a working memory task and creativity. NeuroImage, 55(2), 681–687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.11.052

Thakral, P. P., Madore, K. P., Kalinowski, S. E., & Schacter, D. L. (2020). Modulation of hippocampal brain networks produces changes in episodic simulation and divergent thinking. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(23), 12729–12740. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2003535117

Thakral, P. P., Devitt, A. L., Brashier, N. M., & Schacter, D. L. (2021). Linking creativity and false memory: Common consequences of a flexible memory system. Cognition, 217, 104905. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COGNITION.2021.104905

Thakral, P. P., Yang, A. C., Addis, D. R., & Schacter, D. L. (2021). Divergent thinking and constructing future events: dissociating old from new ideas. Memory, 29(6), 729–743. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2021.1940205

Thakral, P. P., Barberio, N. M., Devitt, A. L., & Schacter, D. L. (2023). Constructive episodic retrieval processes underlying memory distortion contribute to creative thinking and everyday problem solving. Memory & Cognition, 51(5), 1125–1144. https://doi.org/10.3758/S13421-022-01377-0/FIGURES/7

van Kesteren, M. T. R., Ruiter, D. J., Fernández, G., & Henson, R. N. (2012). How schema and novelty augment memory formation. Trends in Neurosciences, 35(4), 211–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2012.02.001

Võ, M.L.-H., Boettcher, S. E., & Draschkow, D. (2019). Reading scenes: How scene grammar guides attention and aids perception in real-world environments. Current Opinion in Psychology, 29, 205–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.03.009

Weiss, S., Wilhelm, O., & Kyllonen, P. (2021). An improved taxonomy of creativity measures based on salient task attributes. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts.https://doi.org/10.1037/ACA0000434

Wixted, J. T. (2007). Dual-process theory and signal-detection theory of recognition memory. Psychological Review, 114(1), 152–176. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.114.1.152

Wixted, J. T., Mickes, L., & Squire, L. R. (2010). Measuring recollection and familiarity in the medial temporal lobe. Hippocampus, 20(11), 1195–1205. https://doi.org/10.1002/HIPO.20854

Yonelinas, A. P. (2002). The nature of recollection and familiarity: A review of 30 years of research. Journal of Memory and Language, 46, 441–517. https://doi.org/10.1006/jmla.2002.2864

Yonelinas, A. P., Ramey, M. M., & Riddell, C. (2022). Recognition memory: The role of recollection and familiarity. In M. J. Kahana & A. D. Wagner (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of human memory. University Press.

Zabelina, D. L., & Condon, D. M. (2020). The Four-Factor Imagination Scale (FFIS): A measure for assessing frequency, complexity, emotional valence, and directedness of imagination. Psychological Research, 84(8), 2287–2299. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00426-019-01227-W

Zabelina, D. L., & Ganis, G. (2018). Creativity and cognitive control: Behavioral and ERP evidence that divergent thinking, but not real-life creative achievement, relates to better cognitive control. Neuropsychologia, 118, 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NEUROPSYCHOLOGIA.2018.02.014

Zabelina, D. L., O’Leary, D., Pornpattananangkul, N., Nusslock, R., & Beeman, M. (2015). Creativity and sensory gating indexed by the P50: Selective versus leaky sensory gating in divergent thinkers and creative achievers. Neuropsychologia, 69, 77–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NEUROPSYCHOLOGIA.2015.01.034

Zabelina, D. L., Saporta, A., & Beeman, M. (2016). Flexible or leaky attention in creative people? Distinct patterns of attention for different types of creative thinking. Memory & Cognition, 44(3), 488–498. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-015-0569-4

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no financial or proprietary interests in any material discussed in this article.

Ethics approval and consent

The methodology for this study was approved by the University institutional review board. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Additional information about stimuli

The scene categories and targets consisted of kitchens (target: frying pan), dining rooms (target: wine glass), bedrooms (target: alarm clock), living rooms (target: coffee mug), and bathrooms (target: toothbrush cup). Eight different object exemplars were used per category, such that the visual features of the target object varied across different scenes within a category. In each scene, only one exemplar of the target object was present, and this was kept consistent across presentations. For example, in each living room scene, there was only one coffee mug present.

The congruent location for a target object was semantically consistent across all scenes in a category, such that targets were placed relative to larger objects with which the target objects co-occur with high probability in daily life (Boettcher et al., 2018; for review of scene grammar see Võ et al., 2019). Specifically, in bathroom scenes, the toothbrush cups were located next to sinks; in dining room scenes, the wine glasses were located on tables (within arm’s reach of a chair); in kitchen scenes, the pans were on stove burners; in bedroom scenes, the alarm clocks were on nightstands; and in living room scenes, the coffee mugs were on coffee tables. The spatial locations of the targets varied across scenes, as illustrated in Fig. 4.

Search time

The target was found on 98.9% of study phase trials. On trials in which the target was found, the average search time was (1) 2045 ms in congruent scenes and 2476 ms in incongruent trials (p = .0001), and (2) 2,482 ms on first presentation and 2,040 ms on second presentation (p < .0001). Thus, both semantic knowledge and episodic memory contributed to search speed in a similar fashion as to spatial accuracy.

Model equations

The equations for the models used for the primary (i.e., non-replication) analyses are specified below (Eqs 1–4). When these equations are discussed with respect to examining fluency and originality separately (in the Sensitivity Analyses section), the “AUT score” variable below was replaced with “fluency” or “originality,” depending on the analysis in question.

Recollection effects

For the difference between recollected and strength-matched familiar scenes, the analysis included old scenes that were given a response of 6 or 5, and the model was specified as:

For the congruency effects, the analysis included recollected scenes (old scenes that were given a response of 6) and was specified as:

Familiarity effects

For familiarity effects, the analyses included scenes across all levels of familiarity strength (old scenes that were given a response of 1-5). For the analysis that examined familiarity irrespective of congruency, the congruency parameter was removed:

Unconscious effects

For unconscious effects, analyses were conducted in old scenes given a response of “sure new,” and new scenes. For the analysis that examined unconscious memory irrespective of congruency, the congruency parameter was removed:

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ramey, M.M., Zabelina, D.L. Divergent thinking modulates interactions between episodic memory and schema knowledge: Controlled and spontaneous episodic retrieval processes. Mem Cogn 52, 663–679 (2024). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-023-01493-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-023-01493-5