Abstract

Objectives

Studies on mortality differentials between international immigrants and non-immigrants produced mixed results. The mortality of interprovincial migrants has been less studied. Our objectives were to compare mortality risk between international immigrants, interprovincial migrants, and long-term residents of the province of Manitoba, Canada, and identify factors associated with mortality among migrants.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective matched-cohort study to examine all-cause and premature mortality of 355,194 international immigrants, interprovincial migrants, and long-term Manitoba residents (118,398 in each group) between January 1985 and March 2019 using linked administrative databases. Poisson regression was used to estimate adjusted incidence rate ratios (aIRR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

The all-cause mortality risk of international immigrants (2.3 per 1000 person-years) and interprovincial migrants (4.4 per 1000) was lower than that of long-term Manitobans (5.6 per 1000) (aIRR: 0.43; 95% CI: 0.42, 0.45 and aIRR: 0.81; 95% CI: 0.80, 0.84, respectively). Compared with interprovincial migrants, international immigrants showed lower death risk (aIRR: 0.50; 95% CI: 0.47, 0.52). Similar trends were observed for premature mortality. Among international immigrants, higher mortality risk was observed for refugees, those from North America and Oceania, and those of low educational attainment. Among internal migrants, those from Eastern Canada had lower mortality risk than those migrating from Ontario and Western Canada.

Conclusion

Migrants had a mortality advantage over non-migrants, being stronger for international immigrants than for interprovincial migrants. Among the two migrant groups, there was heterogeneity in the mortality risk according to migrants’ characteristics.

Résumé

Objectifs

Les études sur les écarts dans la mortalité entre les immigrants internationaux et les non-immigrants produisent des résultats mitigés. La mortalité des migrants interprovinciaux est moins étudiée. Nous avons cherché à comparer le risque de mortalité des immigrants internationaux, des migrants interprovinciaux et des résidents à long terme de la province du Manitoba, au Canada, et à cerner les facteurs associés à la mortalité chez les migrants.

Méthode

Nous avons mené une étude de cohorte assortie rétrospective pour examiner la mortalité toutes causes confondues et la mortalité prématurée chez 355 194 immigrants internationaux, migrants interprovinciaux et résidents à long terme du Manitoba (118 398 dans chaque groupe) entre janvier 1985 et mars 2019 à l’aide de bases de données administratives maillées. Par régression de Poisson, nous avons estimé les rapports de taux d’incidence ajustés (RTAa) avec des intervalles de confiance (IC) de 95 %.

Résultats

Le risque de mortalité toutes causes confondues des immigrants internationaux (2,3 pour 1 000 personnes-années) et des migrants interprovinciaux (4,4 pour 1 000) était plus faible que celui des résidents à long terme du Manitoba (5,6 pour 1 000) (RTAa : 0,43; IC de 95 % : 0,42, 0,45 et RTAa : 0,81; IC de 95 % : 0,80, 0,84, respectivement). Comparativement aux migrants interprovinciaux, les immigrants internationaux présentaient un risque de mortalité plus faible (RTAa : 0,50; IC de 95 % : 0,47, 0,52). Des tendances semblables ont été observées pour la mortalité prématurée. Chez les immigrants internationaux, un risque de mortalité plus élevé a été observé chez les réfugiés, les immigrants de l’Amérique du Nord et de l’Océanie et ceux ayant un faible niveau d’instruction. Chez les migrants intérieurs, ceux de l’Est du Canada présentaient un risque de mortalité plus faible que ceux de l’Ontario et de l’Ouest canadien.

Conclusion

Les migrants présentaient un avantage sur le plan de la mortalité par rapport aux non-migrants; cet avantage était plus prononcé chez les immigrants internationaux que chez les migrants interprovinciaux. Dans ces deux groupes de migrants, il y avait hétérogénéité dans le risque de mortalité selon les caractéristiques des migrants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Studies on the health status of migrants relative to that of non-migrants have produced mixed results. Some studies show immigrant advantage (Abraído-Lanza et al., 1999; Anson, 2004; Rosenwaike & Hempstead, 1990; Sharma et al., 1990) while others show more risk (DesMeules et al., 2005; Gadd et al., 2006; Hollander et al., 2012; Moullan & Jusot, 2014; Norredam et al., 2012; Sundquist & Li, 2006). These heterogeneous results are driven by different study populations, different baseline risk in the host population used for comparisons, different composition of immigrants, and different study methods. For example, in countries that predominantly receive immigrants based on humanitarian grounds (i.e., refugees), such as Sweden, immigrants exhibit higher mortality and heart disease than the native-born (Gadd et al., 2006; Sundquist & Li, 2006). Refugees appear to have a higher mortality risk because of the adverse circumstances preceding or acting during the migration process (DesMeules et al., 2005; Hollander et al., 2012; Norredam et al., 2012). On the other hand, studies conducted in countries that mainly receive economic migrants (i.e., those who self-select themselves for migration), such as Canada and the United States, generally reported lower mortality rates among international immigrants relative to non-migrants (Abraído-Lanza et al., 1999; Anson, 2004; Khan et al., 2017; Rosenwaike & Hempstead, 1990; Sharma et al., 1990), including all-cause mortality and cause-specific mortality (Ng & LHAD Research Team, 2011; Omariba et al., 2014). The concept of migrant mortality advantage (MMA), closely related to the Healthy Immigrant Paradigm (Beiser, 2005), reflects such empirical observations in high-income countries. However, the exact mechanisms behind the low mortality risk among immigrants remain unclear.

Potential mechanisms behind the MMA include selection of healthier individuals for migration, the “salmon bias”, and convergence over time. Selective migration may involve self-migration (i.e., the propensity of healthier individuals to emigrate) and immigration admission policies of the receiving country. Canada selects individuals based on a points system that rewards higher education, work experience, and other attributes conducive to adaptation and success in the labour market. In addition, immigration to Canada may be denied based on a medical examination that makes inadmissible individuals who may pose a danger to public health or safety, or put an excessive demand on health or social services. Selective migration is supported by evidence of favourable sociodemographic characteristics, which are associated with health behaviours and outcomes that are better than those of non-migrants, including mortality (Ali et al., 2004; DesMeules et al., 2005; Omariba et al., 2014). A second popular hypothesis, called the “Salmon Bias”, purports that many migrants return to their homeland after temporary employment, retirement, or severe illness, meaning that their deaths occur in their native land and therefore cannot be captured by the information systems of the country of immigration. The lower mortality of immigrants thus is regarded under this hypothesis as an artefact of including immigrants in the denominator but not in the numerator, creating a “statistically immortal” bias that artificially deflates mortality rates of immigrants (Abraído-Lanza et al., 1999; Wallace & Kulu, 2018). Finally, comparisons of mortality between immigrants and non-immigrants may be affected by a process of convergence (Beiser, 2005) related to duration of residence. While recent immigrants in Canada are generally healthier than the Canadian-born population, exposure to the physical, social, and cultural environment of the destination country may erode the health advantage of recent immigrants (Beiser, 2005; Ng, 2011).

Less is known about the health and mortality of interprovincial migrants. International and interprovincial migration are both influenced by various factors associated with migration (Westphal, 2016; Wingate & Alexander, 2006), such as prospects of upscale income mobility, employment, and social well-being. However, although internal migrants may need to cope with regional adjustments, they do not face challenges specific to foreign migrants such as official language barriers, cultural and political differences, socialization in the local culture, networking, educational gaps, employment and health service access barriers, difficulties of regulations for getting citizenship, and assimilation challenges. Building on the selective migration hypotheses, we expect that both international immigrants and interprovincial migrants will have lower mortality than non-migrants. However, the protective effect of migration is hypothesized to be correlated with the degree of migration, being greater among international immigrants (strong selection) than among interprovincial migrants (weaker selection) for whom the migration experience is less extreme. A secondary objective was to explore mortality differentials among subgroups of international immigrants, defined according to immigrant characteristics such as secondary migration, refugee status, and region of origin, and according to the province of origin of interprovincial migrants.

Methods

Data sources

Information on international immigrants was obtained from the Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) Permanent Resident database that contains the landing records of all legal immigrants to Canada from January 1, 1985 to December 31, 2017. This database also contains sociodemographic and immigration characteristics such as refugee status, country of birth, and knowledge of official languages. The Manitoba Health Insurance Registry (the Registry) was used to identify all Manitoba residents who had registered for provincial universal health care coverage between January 1, 1970 and March 31, 2019, some of whom may be international immigrants who settled in other Canadian provinces before 2018 but moved to Manitoba at any time until March 2019. Internal migrants from other Canadian provinces were also identified in the Registry from 1985 onwards. Mortality data were also obtained from the Registry, since death is a key reason for cancellation of health care coverage.

Study population

We included Manitoba residents of all ages. We included migrants who registered in the Registry between January 1, 1985 and March 31, 2014. The starting point was chosen because of data availability and to allow for a maximum follow-up of 34 years up until March 31, 2019. The exclusion of individuals immigrating after March 31, 2014 was to allow a minimum of 5 years of follow-up until the end of the study period on March 31, 2019. Temporary residents, including students, work permits, and refugee claimants waiting for a decision, could not be included. To estimate the risk of premature mortality, persons aged more than 70 years were censored.

Study design

We conducted a data linkage retrospective population-based matched-cohort study. The linkage of the IRCC Permanent Resident database with the Registry is of high quality, with a linkage rate of 96% (Urquia et al., 2021). The use of retrospective data made it possible to examine the mortality experience of a large pool of immigrants and non-immigrants over three decades.

For meaningful comparisons of mortality according to the type of migrants, international immigrants were 1:1 matched to long-term Manitobans and interprovincial migrants, as follows. First, international immigrants were hard matched without replacement to long-term Manitobans on birth year, sex, and place of residence at the time of their first registration for health care coverage in Manitoba. Second, due to the smaller pool of interprovincial migrants available for matching, international immigrants were matched without replacement to interprovincial migrants based on a propensity score with a caliper of 0.01. The propensity score was based on a logistic model regressing the probability of being an international immigrant and an interprovincial migrant, based on age, sex, place of first residence in Manitoba, and date of immigration to Manitoba (within 5 years). Because the same international immigrant was matched to one long-term Manitoban and one interprovincial migrant, the three formed a matching triad. The adequacy of the matching was deemed satisfactory based on comparisons of sociodemographics, with standardized differences consistently below 10%.

To explore mortality risk within international and interprovincial migrants according to the immigration characteristics and the province of origin, respectively, no matching was needed, and all individuals within each group were included because comparisons were internal to immigrants or interprovincial migrants, respectively.

Variable definitions

Outcome variables

We studied all-cause mortality and premature mortality (deaths up until age 70). The outcome variable was death between January 1985 and March 2019.

Comparison groups

International immigrants were all Manitoba residents with a landing record in the IRCC’s Permanent Resident database. International migrants were further subclassified as refugees, not refugees, primary immigrants (migrated from the country of origin), and secondary immigrants (migrated from a country other than their country of birth) (Urquia et al., 2010; Wanigaratne et al., 2016).

Interprovincial migrants were those who migrated to Manitoba from other Canadian provinces and were not foreign-born. Long-term Manitobans, the reference group, include those who registered to the provincial public health care insurance since birth due to being born in Manitoba after 1970 and came under insurance coverage since birth and those who resided in Manitoba before the creation of the Registry in 1970.

Sociodemographic characteristics

Sociodemographic characteristics available for the whole population were only obtained from the Registry and included year of first registration for health coverage, age, sex, relationship status, and place of residence. Place of residence was used to derive rural residence and neighbourhood income quintiles based on Canadian censuses at the dissemination area level, the smallest geographic unit at which census data are aggregated. The Registry also included the province from which internal migrants originated. Variables only available for international immigrants were obtained from the IRCC Permanent Resident database, including marital status at arrival, educational attainment, refugee status, country of birth, and last permanent residence. The two groups of migrants were categorized by decade of arrival and age at the start of follow-up, which extended to Manitobans who were matched to them.

Data analysis

Kaplan-Meier curves were used to describe the mortality experience of the three groups. Survival time was defined as time from immigration to Manitoba to death, or censorship due to move out-of-province (i.e., date of cancellation of health care coverage) or end of study period, expressed as person-years. For long-term Manitoba residents, we used the date of arrival of their matched immigrants as the date of start of the follow-up. Poisson regression models assessed the association between migrant status and all-cause and premature mortality, expressed as incidence rate ratios that account for differential follow-up time by using the log of person-years of follow-up as an offset variable. For the main analysis comparing the mortality risk of international and interprovincial migrants with that of non-migrants, we used conditional Poisson regression, which takes into account the matching between the comparison groups, according to age, sex, and region of residence at the time of arrival in Manitoba. Models were further adjusted for year of start of health care coverage, relationship status, neighbourhood income quintile, and rural residence. In analyses restricted to international and interprovincial migrants, respectively, where the focus was to explore heterogeneity of risk according to various immigration characteristics within each of these two groups, no matching was needed because the comparisons were internal to immigrants and unconditional Poisson regression analysis was used instead. All analyses were performed in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Ethics approval

Use of the data was approved by the University of Manitoba Health Research Ethics Board (HS22881 (H2019:216)) and was reviewed for data privacy and approved by the Government of Manitoba’s Health Information and Privacy Committee (File No. 2019/2020-17).

Results

Description of the final sample sizes

There were 263,711 international immigrants. Of these, 55,745 were excluded if they arrived on or after April 1, 2014, to allow for a minimum of 5 years of follow-up. We also excluded 552 immigrants with invalid postal code information. The final sample size for this group was 207,414.

There were 278,289 interprovincial migrants whose health care coverage started from 1985 to 2017. After exclusion of 24,661 individuals who did not have an international immigrant match arriving after April 2014 and 1336 with invalid postal code information, the final sample size for interprovincial migrants was 252,292.

In the Registry, there were 727,341 long-term Manitoba residents whose coverage started before 1970 and 692,515 born in the province since then, adding to 1,419,856 Manitobans. After matching on birth year, sex, and place of residence, the ratio of immigrants and interprovincial migrants to long-term Manitobans was 1. The final sample sizes for the matched analyses included 355,194 individuals (118,398 in each comparison group).

Characteristics of the matched study population

Table 1 depicts the characteristics of the three groups. There was an increasing gradient in crude mortality rates from international to interprovincial to long-term Manitobans. There were virtually no differences between the groups with respect to the matching variables year of start of the follow-up, age groups and sex. Differences between groups in the distribution of income quintiles and rural residence were greatly reduced because of the matching by place of residence. International immigrants were the most likely to have spouses, followed by interprovincial migrants. Most immigrants immigrated from Asia, followed by Europe. Most interprovincial migrants to Manitoba migrated from Ontario and Alberta, followed by Saskatchewan and British Columbia.

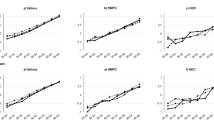

All-cause mortality and premature mortality rates

The all-cause mortality and premature mortality rates in the matched sample were highest for Manitobans (5.57 and 3.41 per 1000 person-years, respectively), followed by interprovincial migrants (4.38 and 2.16, respectively) and then international immigrants (2.30 and 1.03, respectively) (Table 1). Compared to long-term Manitobans, the adjusted risk of death of international migrants was substantially lower than that of Manitobans (aIRR: 0.43; 95% CI: 0.42, 0.45 for all-cause mortality and aIRR: 0.35; 95% CI 0.33–0.37 for premature mortality) (Table 2). Similarly, interprovincial migrants were less likely to experience all-cause and premature mortality relative to Manitobans (aIRR: 0.81; 95% CI: 0.80, 0.84 and aIRR: 0.70; 95% of CI: 0.66, 0.74, respectively). For all-cause and premature mortality, the rates of international migrants were significantly lower compared to those of interprovincial migrants (aIRR: 0.54; 95% CI: 0.51, 0.56 and 0.49, 95% CI 0.46, 0.53, respectively). These associations did not appreciably differ according to sex (Table 2). In analyses stratified by age at arrival groups, the mortality advantage of international immigrants was observed in all of them (data not shown), as it was observed in analyses stratified by period of the start of the follow-up (1985–1994, 1995–2004 and 2005–2014) (Supplemental Tables S1 and S2). Kaplan-Meier curves (Fig. 1) show that the mortality advantage of international immigrants was apparent across time after migration. The downward curvilinear pattern for all three groups, more visible for all-cause mortality (Fig. 1, left), indicates an acceleration of the risk of death, parallel to increasing age and time since migration.

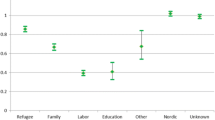

Mortality according to the characteristics of foreign-born migrants

Table 3 presents the rates for all-cause and premature death among all (matched and non-matched) international immigrants. Refugees had higher mortality risk relative to non-refugees, after adjustment. Secondary immigrants had higher mortality rates before but not after adjustment, due to being older on average than primary immigrants. Single never married individuals had higher mortality risk than those with a spouse, after adjustment. An inverse relationship existed between education level and risk of death; immigrants who had secondary education or less and those with some post-secondary education had higher all-cause and premature mortality risk than those with a university degree. Southeast Asians, South Asians, the rest of Asians, and those from Latin America and the Caribbean had a lower risk of all-cause mortality than Western Europeans, but these advantages were not observed for premature mortality. Immigrants from North America and Oceania, a group composed of 86.8% of immigrants from the USA, had a higher risk of both all-cause and premature mortality. A positive association among Eastern Europeans was observed for premature mortality but was no longer statistically significant for all-cause mortality, after adjustment.

Mortality among interprovincial migrants

Table 4 shows that migrants from all provinces except British Columbia—particularly those from Eastern Canada—had lower death risk than those from Ontario, the most populous Canadian province.

Discussion

Main findings

We found that both international immigrants and interprovincial migrants had lower mortality risk than the local Manitoban population. The migrant mortality advantage, however, was stronger for international than for interprovincial migrants. Among the two migrant groups, there was heterogeneity in the mortality risk according to migrants’ characteristics, mainly higher risk among refugees, those from North America and those with low educational attainment. Internal migrants from the eastern Canadian provinces had lower mortality risk.

Limitations

There were some limitations to this study. Sociodemographic information was only collected from the permanent residence data and the Registry. Temporary residents, such as international visa students, work permit holders, and refugee claimants waiting for a decision, were not included in this study. Although immigrants lost to follow-up were censored, it is possible that some of them may have died shortly after remigrating and could not contribute to the numerator, thus deflating their mortality risk (Andersson & Drefahl, 2017; Wallace & Kulu, 2018). This study could not distinguish those who left the province and returned to their country or province of origin due to ill health from those who remigrated to another destination and may be healthier. Some immigrant characteristics were measured at the time of arrival and could not be updated at a later time, such as education and marital status. This may have affected the efficiency of the adjustment and contributed to residual confounding. We also lacked measures of morbidity and information on the medical history of migrants before arriving in the country and the province. Finally, since the focus of the study was to examine the overall mortality gradient of international and interprovincial migrants and non-migrants, more detailed examinations of specific mechanisms that may affect particular subgroups defined by place of origin, period of arrival, and other migrant characteristics were beyond the scope of this study.

Interpretation

This study confirmed the lower mortality risk among immigrants in Canada. We found that both international and interprovincial migrants have a mortality advantage over the local Manitoban population. We also found that interprovincial migrants had death rates that are intermediate between those of the other two groups. This suggests that while migrants in general are healthier than non-migrants, international migration is associated with a stronger protective effect than internal migration, which may be a reflection of a stronger selection for migration. While interprovincial migrants share with the local population the language, political and cultural similarities, their migration decisions may be driven by better health status, which may be behind their mortality advantage (Westphal, 2016). However, since the migration experience of interprovincial migrants is less radical than that of international immigrants, so is the effect. Results also indicate that the difference between the rates of all-cause and premature mortality was higher between the two groups of migrants over Manitobans than between the two migrant groups. This observation suggests an influence of a lower life expectancy of Manitobans in general and of Indigenous groups in particular, which are prevalent in Manitoba and known to have lower life expectancy than the rest of the Manitoba population (Katz et al., 2021).

In analyses restricted to international immigrants, we found that refugees had higher all-cause and premature mortality risk than non-refugees, after adjustment. This association may reflect specific determinants of health not shared by their non-refugee counterparts, such as involuntary and forced migration, political unrest and persecution, possible exposure to refugee camps, and limited access to quality health care and living conditions during the migration process (Wanigaratne et al., 2016). In addition, in 2002, the Canadian Immigration and Refugee Protection Act updated immigration selection criteria by exempting certain immigrant classes (e.g., refugees and family class) from inadmissibility on health grounds (Government of Canada, 2001), which may have also contributed to the admission of less healthy refugees. Secondary immigrants exhibited higher unadjusted mortality rates, due to being older on average than primary immigrants, but the associations disappeared after adjustment. These findings do not support a secondary migration advantage in mortality that has been observed in reproductive health (Urquia et al., 2010), particularly among non-refugees (Wanigaratne et al., 2016). Finally, there were variations according to immigrants’ birthplace. Consistent with previous Canadian studies (Ng, 2011; Ng & LHAD Research Team, 2011), Asian immigrants had low mortality rates, presumably due to more favourable diet and health behaviours. East Europeans exhibited higher premature mortality in our study, which may be related to a higher prevalence of risk factors for chronic diseases and death, such as smoking, alcohol, and poor diet (McKee & Shkolnikov, 2001; Powles et al., 2005). Less clear are the reasons behind the excess mortality among those from North America and Oceania, a subgroup composed predominantly of immigrants from the USA. The possibility that migration from the USA to Manitoba is associated with a negative health selection should be investigated in future studies, without disregarding the potential contribution of various First Nations or American Indian Nations, which have cross-border rights due to their original territories and family and social life being disrupted by the US-Canada border (Assembly of First Nations, 2020).

In analyses restricted to interprovincial migrants, we found that migrants from the province of British Columbia had higher unadjusted mortality risk than migrants from Ontario. However, the excess risk was explained by observed individual characteristics. More robust is the lower mortality observed among those from Eastern Canada (Atlantic Canada and Quebec). Although we lacked additional data (i.e., socioeconomic status before migration, occupation, or reasons for migration) that may help explain these patterns, the selection hypothesis may suggest that migration from better-off places like British Columbia, which has a strong economy and the highest life expectancy among all Canadian provinces (Zhang & Rasali, 2015), may be negatively selected for health, whereas migration from provinces with economies either weaker than or similar to Manitoba’s, such as those of Eastern Canada (Statistics Canada, 2021), may be positively selected for health.

Conclusion

This study found a mortality gradient according to the degree of migration, being lower among international immigrants, intermediate among interprovincial migrants, and highest among long-term Manitobans. This gradient is likely to reflect different levels of selection for migration; the stronger the selection, the lower the mortality. Our findings suggest that efforts to achieve gains in life expectancy in the province of Manitoba may be better focused on the local population. Despite an overall mortality advantage, heterogeneity in mortality risk exists within immigrants. Understanding the protective factors that underlie the migrant mortality advantage may help with devising prevention strategies for the local population and the migrant subgroups at higher risk, such as refugees and those from the USA.

Contributions to knowledge

What does this study add to existing knowledge?

-

Our study provides novel evidence of the role of selective migration on mortality by including interprovincial migrants, a group rarely studied.

-

The stronger the selection associated with migration, the stronger the mortality advantage, as evidenced by the increasing mortality gradient from international immigrants to interprovincial migrants to long-term Manitoba residents.

-

The study also identifies factors associated with mortality differentials within migrant groups.

What are the key implications for public health interventions, practice, or policy?

-

Given the mortality advantage of both international immigrants and interprovincial migrants with respect to Manitoba residents, efforts to achieve gains in life expectancy in the province of Manitoba may be better focused on the local population and on high-risk migrant groups, such as refugees.

Data availability

This study’s data were accessed from the Manitoba Population Research Data Repository at Manitoba Centre of Health Policy. Use of the provincial data was approved by Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living. The study data can be accessed upon obtaining the required permissions.

Code availability

All programming was performed with SAS. SAS code is available from the authors upon request.

References

Abraído-Lanza, A. F., Dohrenwend, B. P., Ng-Mak, D. S., & Turner, J. B. (1999). The Latino mortality paradox: A test of the “salmon bias” and healthy migrant hypotheses. American Journal of Public Health, 89(10), 1543–1548.

Ali, J. S., McDermott, S., & Gravel, R. G. (2004). Recent research on immigrant health from Statistics Canada’s population surveys. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 95(3), I9–I13. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03403659

Andersson, G., & Drefahl, S. (2017). Long-distance migration and mortality in Sweden: Testing the salmon bias and healthy migrant hypotheses. Population, Space and Place, 23(4). https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2032

Anson, J. (2004). The migrant mortality advantage: A 70-month follow-up of the Brussels population. European Journal of Population, 20(3), 191–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-004-0883-1

Assembly of First Nations. (2020). Registration and the Canada-United States border. Available at: https://www.afn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/07-19-02-06-AFN-Fact-Sheet-Registration-and-the-Canada-US-Border-final-revised.pdf Last accessed: May 26, 2021.

Beiser, M. (2005). The health of immigrants and refugees in Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 96(2), S30–S44. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03403701

DesMeules, M., Gold, J., McDermott, S., Cao, Z., Payne, J., Lafrance, B., et al. (2005). Disparities in mortality patterns among Canadian immigrants and refugees, 1980-1998: Results of a national cohort study. Journal of Immigrant Health, 7(4), 221–232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-005-5118-y

Gadd, M., Johansson, S. E., Sundquist, J., & Wändell, P. (2006). Are there differences in all-cause and coronary heart disease mortality between immigrants in Sweden and in their country of birth? A follow-up study of total populations. BMC Public Health, 6, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-6-102

Government of Canada. (2001). Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (s.c.2001, c.27). Minister of Justice. Justice Laws Website. Available at: https://www.laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/I-2.5/page-6.html#docCont. Accessed 22 May 2018.

Hollander, A. C., Bruce, D., Ekberg, J., Burström, B., Borrell, C., & Ekblad, S. (2012). Longitudinal study of mortality among refugees in Sweden. International Journal of Epidemiology, 41(4), 1153–1161. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dys072

Katz, A., Urquia, M. L., Star, L., Lavoie, J. G., Taylor, C., Château, D., Enns, J. E., Tait, M. J., & Burchill, C. (2021). Changes in health indicator gaps between First Nations and other residents of Manitoba. CMAJ, 193(48), E1830–E1835. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.210201

Khan, A., Urquia, M., Kornas, K., Henry, D., Cheng, S., Bornbaum, et al. (2017). Socioeconomic gradients in all-cause, premature and avoidable mortality among immigrants and long-term residents using linked deaths records in Ontario, Canada. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 71(7), 625–632. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2016-208525

McKee, M., & Shkolnikov, V. (2001). Understanding the toll of premature death among men in Eastern Europe. British Medical Journal, 323(7320), 1051–1055. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.323.7320.1051

Moullan, Y., & Jusot, F. (2014). Why is the “healthy immigrant effect” different between European countries? European Journal of Public Health, 24(SUPPL.1), 80–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cku112

Ng, E. (2011). The healthy immigrant effect and mortality rates. Health Reports, 22(4), 25–29.

Ng, E., & LHAD Research Team. (2011). Insights into the healthy immigrant effect: Mortality by period of immigration and birthplace. Statistics Canada. Health Reports, 8, 1–16.

Norredam, M., Olsbjerg, M., Petersen, J. H., Juel, K., & Krasnik, A. (2012). Inequalities in mortality among refugees and immigrants compared to native Danes - A historical prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-757

Omariba, D. W. R., Ng, E., & Vissandjée, B. (2014). Differences between immigrants at various durations of residence and host population in all-cause mortality, Canada 1991-2006. Population Studies, 68(3), 339–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324728.2014.915050

Powles, J. W., Zatonski, W., Vander Hoorn, S., & Ezzati, M. (2005). The contribution of leading diseases and risk factors to excess losses of healthy life in Eastern Europe: Burden of disease study. BMC Public Health, 5, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-5-116

Rosenwaike, I., & Hempstead, K. (1990). Mortality among three Puerto Rican populations: Residents of Puerto Rico and migrants in New York City and in the balance of the United States, 1979-81. International Migration Review, 24(4), 684–702.

Sharma, R. D., Michalowski, M., & Verma, R. B. (1990). Mortality differentials among immigrant populations in Canada. International Migration, 28(4), 443–450.

Statistics Canada. (2021). “Gross domestic product, expenditure-based, provincial and territorial, annual”. Available at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/cv.action?pid=3610022201 Last accessed: May 27, 2021.

Sundquist, K., & Li, X. (2006). Coronary heart disease risks in first- and second-generation immigrants in Sweden: A follow-up study. Journal of Internal Medicine, 259(4), 418–427. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01630.x

Urquia, M., Walld, R., Wanigaratne, S., Eze, N., Azimaee, M., McDonald, J. T., & Guttmann, A. (2021). Linking national immigration data to provincial repositories: The case of Canada. International Journal of Population Data Science, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.23889/ijpds.v6i1.1412

Urquia, M. L., Frank, J. W., & Glazier, R. H. (2010). From places to flows. International secondary migration and birth outcomes. Social Science and Medicine, 71(9), 1620–1626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.08.006

Wallace, M., & Kulu, H. (2018). Can the salmon bias effect explain the migrant mortality advantage in England and Wales? Population, Space and Place, 24(8). https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2146

Wanigaratne, S., Cole, D. C., Bassil, K., Hyman, I., Moineddin, R., & Urquia, M. L. (2016). The influence of refugee status and secondary migration on preterm birth. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 70(6), 622–628. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2015-206529

Westphal, C. (2016). Healthy migrants? Health selection of internal migrants in Germany. European Journal of Population, 32(5), 703–730. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-016-9397-x

Wingate, M. S., & Alexander, G. R. (2006). The healthy migrant theory: variations in pregnancy outcomes among US-born migrants. Social Science and Medicine, 62(2), 491–498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.06.015

Zhang, L. R., & Rasali, D. (2015). Life expectancy ranking of Canadians among the populations in selected OECD countries and its disparities among British Columbians. Archives of Public Health, 73(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-015-0065-0

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy (MCHP) for the use of data contained in the Manitoba Population Research Repository under project #2019-012. The results and conclusions are those of the authors and no official endorsement by the MCHP, Manitoba Health, or other data providers is intended or should be inferred. We thank Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada for the sharing of data and for reviewing the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported through funding from Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living and the Canadian Foundation of Innovation. SB was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant awarded to MLU (grant number FDN-154280). MLU holds a Canada Research Chair in Applied Population Health (grant number 950-231324).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SB and MLU conceived the study. All authors contributed to the study design, analyzed the data, and interpreted the results. SB drafted the first version of the manuscript. MLU supervised the study. All authors critically appraised the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Use of the data was approved by the University of Manitoba Health Research Ethics Board (HS22881 (H2019:216)) and was reviewed for data privacy and approved by the Government of Manitoba’s Health Information and Privacy Committee (File No. 2019/2020-17).

Consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 26 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Debbarman, S., Prior, H., Walld, R. et al. Assessing the migrant mortality advantage among foreign-born and interprovincial migrants in Manitoba, Canada. Can J Public Health 114, 441–452 (2023). https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-022-00727-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-022-00727-4