Abstract

Background

Food safety is of global importance and has been of concern in university settings in recent years. However, effective methods to conduct food safety education are limited. This study aims to evaluate the effects of an intervention on food safety knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) by social media, WeChat, among university students.

Methods

A quasi-experimental study was conducted in Chongqing, China. Two departments were recruited randomly from a normal university and a medical university. One department from each university was randomly selected as the intervention group and the other as the control group. All freshmen students in each selected department were chosen to participate in this study. One thousand and twenty-three students were included at baseline, and 444 students completed the study. This intervention was conducted through food safety-related popular science articles with an average of three articles per week released by WeChat official accounts called "Yingyangren" for two months to the intervention group. No intervention was conducted in the control group. An independent t-test was used to test statistical differences in the food safety KAP scores between the two groups. A paired t-test was used to test statistical differences in the food safety KAP scores between before and after the intervention. And quantile regression analysis was conducted to explore the difference between the two groups across the quantile levels of KAP change.

Results

After the intervention, compared with control group, participants in the intervention group did not score significant higher on knowledge (p = 0.98), attitude (p = 0.13), and practice (p = 0.21). And the scores of food safety knowledge and practices slightly improved after the intervention both in the intervention group (p = 0.01 and p = 0.01, respectively) and in the control group (p = 0.0003 and p = 0.0001, respectively). Additionally, the quantile regression analysis showed that the intervention had no effect on improving the food safety KAP scores.

Conclusions

The intervention using the WeChat official account had limited effects on improving the food safety KAP among the university students. This study was an exploration of food safety intervention using the WeChat official account; valuable experience can be provided for social media intervention in future study.

Trial registration

ChiCTR-OCH-14004861.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Food safety is a global health goal. Foodborne diseases represent a growing public health problem in developed and develo** countries [1]. Global estimates that 31 foodborne hazards cause 600 million foodborne illnesses and 420,000 deaths annually, resulting in the loss of 33 million healthy life years [2]. According to Foodborne Diseases Surveillance Network, a total of 2,401 foodborne diseases occurred and resulted in 21,374 cases and 139 deaths in the 29 provinces of mainland China in 2015 [3]. Moreover, cases of foodborne diseases were often under-reported, especially in develo** countries [4].

Food safety has been of concern in university settings in recent years. University students are one of the high-risk population groups for food poisoning, who have inadequate knowledge [5,6,7] and risky food safety practices. University students typically eat out [8], consume takeaway food [9] and have unhealthy food handling [10]. Normal and medical university students belong to a population with unique features. Normal universities provide teacher education in China, in which various types of teachers were trained. Food safety cognition and practices of teachers and doctors are beneficial to their food safety incidence prevention and are expected to play important roles in health education and promotion after their graduation [6].

The World Health Organization stated that food safety education is vital in eliminating or reducing food contaminants and preventing micro-organism growth at levels that cause disease [11]. Some food safety intervention programs were conducted targeting food service employees [12,13,14] and students [15, 16], and traditional education methods were often used [17, 18]. These methods included providing reading materials (e.g. booklets and leaflets), conducting lectures and presentations and distributing posters [19]. A previous study demonstrated that methodology and approach adopted are important for a successful food safety training programme [20]. The limited effectiveness of traditional health education [21, 22] leads health education and promotion researchers worldwide to explore effective and innovative ways, which attempt to increase the efficacy of their interventions based on the worldwide web and other digital media [23].

One of the leading social networks worldwide, WeChat, developed by the Chinese company Tencent, placed fifth in the number of active users and had over 1.1 billion monthly active users in the first quarter of 2019 [24]. In accordance with the statistics provided by the China Internet Network Information Center in 2019 [25], the percentage of WeChat users reached 83.4% in China. Most of its users were between the ages of 20 and 29 by the end of December 2018. Like Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, WeChat offers a free instant messaging application for smartphones that enables the exchange of voice, text, pictures, videos and location information via mobile phone indexes [26]. WeChat official account is based on a new functional module. WeChat users can register an official account, which enables them to push feeds, interact with one another and provide subscribers with service. In addition, subscribers can read messages and communicate with others through these official accounts [27]. At present, WeChat, as a cost-effective and peer-to-peer supported educational tool, has been used for conducting health education or promotion to modify behaviours [27,28,29,30]. However, concerns exist about reliability and quality control of disseminated information via social media, as well as concerns about the intervention effects on promoting healthy behaviours [31,32,33]. Understanding the effect of WeChat on users is important as it gains popularity as a health intervention platform.

At present, most intervention strategies for improving food safety cognition and practices are mainly based on traditional education methods. Previous studies on social media and food safety were targeted at communication of food safety risks or public opinion on the Internet regarding food safety [27, 34, 46, 47], and medical students may have no time and energy to participate in this intervention. Thus, new methods to mobilize the enthusiasm and increase the participation of university students should be explored and attempted in a future intervention study, such as sending links or emails to invite participants to view relevant content [48]. In addition, the duration of social media intervention should avoid the period when university students would be busy with many examinations.

Secondly, part of intervention information through articles published in "Yingyangren" WeChat official account may not be appropriate for university students. "Yingyangren" WeChat official account is a relatively experienced platform for delivering health knowledge, university students in this intervention are a part of this official account followers. Some contents of the articles provided are related to popular issues to attract interest of official account followers, but the relevance to university students is under considered, such as the veterinary drug residue of meat and pesticide residues in vegetables; these topic can be hardly put into practice by the Chinese university students who mostly live a campus life. Information intervention may be invalid. WeChat official account should be set up specifically in future intervention for target population audience. In addition, KAP model was used to evaluate the intervention effects in this study. In order to ensure the reliability and validity of the KAP questionnaire, the items of questionnaire were selected. Hence, the final questions used to measure the intervention effects were not exactly kept in line with the intervention materials/science articles; this could be the one of the reasons for the limited intervention effects.

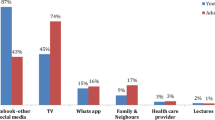

Thirdly, diversified health information acquisition amongst university students [49] may be another reason for the limited effects. In this study, popular science articles released by the "Yingyangren" WeChat official account would be re-tweeted via WeChat moment, QQ or Micro-blog to increase accessibility amongst the intervention group. However, during the process, the participants in the control group may also obtain the intervention information indirectly. Moreover, results of this study showed that more than half of the participants in the control group obtained food safety-related knowledge via other social media or network platforms. In addition to the provided intervention platform and information, the participants can also obtain food safety-related information through other channels, which may cause a considerable improvement in food safety knowledge and practices in the intervention and control groups after the intervention and the no difference between-group findings in this study.

Intervention strategies of social media could enhance the success rate, such as the integrated use of discussion boards, learning modules, tailored feedback and interactivity [50, 51]. However, in this study, the WeChat official account was used to release food safety-related popular science articles, and learning modules were mainly intervention strategies for participants, whilst other functions of WeChat are not utilized efficiently in this study. This factor may be considered in analysing the limited intervention effects. In future studies, discussion boards, tailored feedback and interactivity of the WeChat official account should be utilized efficiently to enhance the success rate. Moreover, using social media as part of a complex intervention, which can combine the WeChat official account for online food safety education and offline lectures or food safety-related compulsory courses, could be conducted amongst university students.

The results of this study showed that intervention materials had a certain degree of readability and effectiveness. In addition, the participants had a relatively high level of satisfaction with the "Yingyangren" WeChat official account for conducting food safety education intervention. Most participants trusted the food safety-related popular science articles released by "Yingyangren" WeChat official account and agreed that the information could help to improve their food safety knowledge and correct their inappropriate behaviours. However, subjective assessment was not in accordance with the intervention results. The possible explanation for the inconsistent results could be that university students is relatively optimistic and may exaggerate the effects intervention, and the questions used to measure the intervention effects is somewhat difficult for them. Additional studies on how to efficiently use the WeChat official account to improve the food safety knowledge and correct inappropriate food safety behaviours of university students should be conducted.

This study has certain limitations. Firstly, this study did not design a targeted educational program for the student audience, and "Yingyangren" WeChat official account was not specifically established for this intervention group; part of intervention information may not be appropriate for university students; the KAP questionnaire was not exactly kept in line with the intervention materials. Future intervention by social media needs to be strengthened in these three aspects. Secondly, the intervention duration might not be enough. Practice change needs regular long-term education. One systematic review showed that the duration of social media intervention ranged from three months to two years [32]. However, the duration of this study was two months. The study duration could be increased to examine the intervention effects in future studies. Moreover, evaluating the food safety KAP during the two-month intervention process should be considered instead of just evaluating the KAP before and after the intervention, such as conducting an assessment after completing the three or four-time interventions. Thirdly, interaction characteristics in social media are one of the most common features [32, 52, 53], such as message boards and consulting section in this study. However, very few participants expressed their own opinions or raised questions about released food safety-related popular science articles. How to efficiently use the essential interaction characteristics should also be studied. Fourthly, this study relied on self-report, which may introduce bias caused by dishonesty, measurement flaws or social desirability bias. Fifthly, our intervention was implemented in small sample. Generalizability to larger units would be necessary. Finally, usage of Internet interventions was typically low, and high attrition rates are one of the possible reasons [32]. Similarly, high attrition rate in this study could introduce bias into the results, although no difference exists in the socio-demographic characteristics between the intervention and control groups before and after the intervention. Challenges of adherence and kee** the participants engaged, incentive motivation and end-user engagement during the development of the intervention could be attempted in future research to decrease the attrition [54, 55].

Conclusion

The WeChat official account intervention had a limited effect on improving the food safety KAP amongst university students. This study was an exploration of food safety intervention using the WeChat official account; valuable experience can be provided for social media intervention in future study. Given that university students are the key population for food safety intervention and social media has become the main method for them to obtain information, powerful trials and meta-analyses are required to explore how to efficiently use the WeChat official account intervention on food safety health education and how to improve the intervention effects in future studies.

Availability of data and materials

Data set underlying the findings are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- KAP:

-

Knowledge, attitudes and practices

References

Velusamy V, Arshak K, Korostynska O, Oliwa K, Adley C. An overview of foodborne pathogen detection: in the perspective of biosensors. Biotechnol Adv. 2010;28(2):232–54.

World Health Organization. Key facts of Food safety. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/food-safety. Accessed 3 October 2019.

Fu P, Wang L, Chen J, Bai G, Xu L, Wang S, et al. Analysis of foodborne disease outbreaks in mainland China in 2015. Chin J Food Hyg. 2019;31(1):64–70.

Odeyemi O. Public health implications of microbial food safety and foodborne diseases in develo** countries. Food Nutr Res. 2016. https://doi.org/10.3402/fnr.v60.29819.

Ferk CC, Calder BL, Camire ME. Assessing the Food safety knowledge of university of Maine students. J Food Sci Educ. 2016;15(1):14–22.

Luo X, Xu X, Chen H, Bai R, Zhang Y, Hou X, et al. Food safety related knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) among the students from nursing, education and medical college in Chongqing, China. Food Control. 2019;95:181–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2018.07.042.

Stratev D, Odeyemi OA, Pavlov A, Kyuchukova R, Fatehi F, Bamidele FA. Food safety knowledge and hygiene practices among veterinary medicine students at Trakia University, Bulgaria. J Infect Public Health. 2017;10(6):778.

Hu P, Wenjie H, Ruixue B, Fan Z, Manoj S, Zumin S, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and behaviors related to eating out among university students in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(7):696.

Jiang Y, Wang J, Wu S, Li N, Wang Y, Liu J, et al. Association between take-out food consumption and obesity among chinese university students: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(6):1071. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16061071.

Morrone M, Rathbun A. Health education and food safety behavior in the university setting. J Environ Health. 2003;65(7):9.

World Health Organization. Foodborne diseases: a focus on health education. 2000.

Acikel CH, Ogur R, Yaren H, Gocgeldi E, Ucar M, Kir T. The hygiene training of food handlers at a teaching hospital. Food Control. 2008;19(2):186–90.

Malhotra R, Lal P, Krishna Prakash S, Daga MK, Kishore J. Evaluation of a health education intervention on knowledge and attitudes of food handlers working in a Medical College in Delhi, India. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2008;20(4):277–86.

Salazar J, Ashraf H-R, Tcheng M, Antun J. Food service employee satisfaction and motivation and the relationship with learning food safety. J Culin Sci Technol. 2005;4(2–3):93–108.

Zhou WJ, Xu XL, Li G, Sharma M, Qie YL, Zhao Y. Effectiveness of a school-based nutrition and food safety education program among primary and junior high school students in Chongqing, China. Glob Health Promot. 2014;23(1):37.

Diplock K, Dubin J, Leatherdale S, Hammond D, Jones-Bitton A, Majowicz S. Observation of high school students’ food handling behaviors: do they improve following a food safety education intervention? J Food Prot. 2018;81:917–25. https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-17-441.

Singh AK, Dudeja P, Kaushal N, Mukherji S. Impact of health education intervention on food safety and hygiene of street vendors: A pilot study. Med J Armed Forces India. 2016;72(3):265–9.

Young I, Waddell L, Harding S, Greig J, Mascarenhas M, Sivaramalingam B, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of food safety education interventions for consumers in developed countries. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):822.

Medeiros CO, Cavalli SB, Salay E. Proen?a RPC: Assessment of the methodological strategies adopted by food safety training programmes for food service workers: a systematic review. Food Control. 2011;22(8):1136–44.

Nieto-Montenegro S, Brown JL, LaBorde LF. Development and assessment of pilot food safety educational materials and training strategies for Hispanic workers in the mushroom industry using the Health Action Model. Food Control. 2008;19(6):1–633.

DiCenso A. Interventions to reduce unintended pregnancies among adolescents: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2002;324(7351):1426–30.

Wells J, Barlow J, Stewart-Brown S. A systematic review of universal approaches to mental health promotion in schools. Health Educ. 2003;103(4):197–220.

Bauman A, Chau J. The role of media in promoting physical activity. J Phys Act Health. 2009;6 Suppl 2(Supplement 2):S196-210.

Statista. Number of monthly active WeChat users from 1st quarter 2012 to 1st quarter 2019 (in millions) 2019. https://www.statista.com/statistics/255778/number-of-active-wechat-messenger-accounts/. Accessed 8 Oct 2019.

China Internet Network Information Center. The 43rd China Statistical report on internet development. 2019. http://cnnic.cn/hlwfzyj/hlwxzbg/. Accessed 3 July 2019.

Wei L, Le QH, Yan JG, **g S. Using WeChat official accounts to improve malaria health literacy among Chinese expatriates in Niger: an intervention study. Malar J. 2016;15(1):567.

Wei H, Shi M, Hong X, Pu X. Influencing factor of food safety food safety internet public opinion transmission by Weibo among netizens. China Popul Resour Environ. 2016;26(5):25.

Guo Y, Xu Z, Qiao J, Hong YA, Zhang H, Zeng C, et al. Development and feasibility testing of an mHealth (text message and WeChat) intervention to improve the medication adherence and quality of life of people living with HIV in China: pilot randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018;6(9):e10274-e. https://doi.org/10.2196/10274.

Guo Y, Hong YA, Qiao J, Xu Z, Zhang H, Zeng C, et al. Run4Love, a mHealth (WeChat-based) intervention to improve mental health of people living with HIV: a randomized controlled trial protocol. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):793. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5693-1.

He C, Wu S, Zhao Y, Li Z, Zhang Y, Le J, et al. Social media-promoted weight loss among an occupational population: cohort study using a WeChat mobile phone app-based campaign. J Med Intern Res. 2017;19(10):e357-e. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.7861.

Korda H, Itani Z. Harnessing social media for health promotion and behavior change. Health Promot Pract. 2013;14(1):15–23.

Williams G, Hamm MP, Shulhan J, Vandermeer B, Hartling L. Social media interventions for diet and exercise behaviours: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open. 2014;4(2):e003926.

Taggart T. Social media and HIV: a systematic review of uses of social media in HIV communication. J Med Intern Res. 2015;17(11):e248.

Overbey KN, Jaykus L-A, Chapman BJ. A systematic review of the use of social media for food safety risk communication. J Food Prot. 2017;80(9):1537.

Peng Y, Li J, **a H, Qi S, Li J. The effects of food safety issues released by we media on consumers’ awareness and purchasing behavior: a case study in China. Food Policy. 2015;51:44–52.

**e XW, Sun YH, Luan GC. Study on the college students' influencing factor of cognition and educational countermeasure of food safety. Chin J Health Educ. 2014.

Zhu R, Xu X, Zhao Y, Sharma M, Shi Z. Decreasing the use of edible oils in China using WeChat and theories of behavior change: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. 2018.

Morgan AJ, Rapee RM, Bayer JK. Increasing response rates to follow-up questionnaires in health intervention research: randomized controlled trial of a gift card prize incentive. Clin Trials. 2017;14(4):1740774517703320.

Rutterford C, Copas A, Eldridge S. Methods for sample size determination in cluster randomized trials. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(3):1051–67.

Zhou WJ, Xu XL, Li G, Sharma M, Qie YL, Zhao Y. Effectiveness of a school-based nutrition and food safety education program among primary and junior high school students in Chongqing. China Glob Health Promot. 2016;23(1):37–49.

Bai L, Cai Z, Lv Y, Wu T, Sharma M, Shi Z, et al. Personal involvement moderates message framing effects on food safety education among medical university students in Chongqing, China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(9):2059. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15092059.

Ozilgen S. Food safety education makes the difference: food safety perceptions, knowledge, attitudes and practices among Turkish university students. J Verbr Lebensm. 2011;6(1):25–34.

Horgan Á, Sweeney J. University students’ online habits and their use of the Internet for health information. Clin Comput Inform Nurs. 2012;30(31):TC19.

Syn SY, Kim SU. College students’ health information activities on facebook: investigating the impacts of health topic sensitivity, information sources, and demographics. J Health Commun. 2016;21(7):1.

Wang M. A review of online information behaviors of college students in China. Lib Inform. 2016;s1:87–9.

Sreeramareddy CT, Shankar PR, Binu VS, Mukhopadhyay C, Ray B, Menezes RG. Psychological morbidity, sources of stress and co** strategies among undergraduate medical students of Nepal. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7(1):26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-7-26.

Waqas A, Khan S, Sharif W, Khalid U, Ali A. Association of academic stress with slee** difficulties in medical students of a Pakistani medical school: a cross sectional survey. PeerJ. 2015;3:e840. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.840.

Spittaels H, Bourdeaudhuij ID, Vandelanotte C. Evaluation of a website-delivered computer-tailored intervention for increasing physical activity in the general population. Prev Med. 2007;44(3):209–17.

Wang Y, Du J. Online health information research and analysis on female students of a university in Bei**g. Chin J School Health. 2016;37(9):1336–41.

Spring B, Duncan JM, Janke EA, Kozak AT, Hedeker D. Integrating technology into standard weight loss treatment a randomized controlled trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(2):105–11.

Kohl L, Crutzen R, Vries N. Online prevention aimed at lifestyle behaviors: a systematic review of reviews. J Med Intern Res. 2013;15:e146. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2665.

Anand T, Nitpolprasert C, Ananworanich J, Pakam C, Nonenoy S, Jantarapakde J, et al. Innovative strategies using communications technologies to engage gay men and other men who have sex with men into early HIV testing and treatment in Thailand. J Virus Erad. 2015;1(2):111–5.

Cao B, Gupta S, Wang J, Hightow-Weidman LB, Tucker JD. Social media interventions to promote HIV Testing, linkage, adherence, and retention: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Intern Res. 2017;19(11): e394.

Hartling L, Scott S, Pandya R, Johnson D, Bishop T, Klassen TP. Storytelling as a communication tool for health consumers: development of an intervention for parents of children with croup, Stories to communicate health information. BMC Pediatr. 2010;10(1):64.

Spring B, Schneider K, McFadden HG, Vaughn J, Kozak AT, Smith M, et al. Multiple behavior changes in diet and activity. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(10):789.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the support of the project of intervention on the cognition and practices of food safety for college students through self-social media funded by the Humanities and Social Science Fund of Ministry of Education of China (15YJA860020) and the project of research and application demonstration of co-regulation information technology in food safety governance funded by National Key R&D Program of China (2017YF1602000). Also, we would like to thank all the teachers and class leaders who helped us coordinate the survey. We thank all the participants for their support of this project. We also would like to acknowledge all the investigators who participated in the survey.

Funding

This work was supported by the project of intervention on the cognition and practices of food safety for college students through self-social media funded by the Humanities and Social Science Fund of Ministry of Education of China (15YJA860020) and the project of research and application demonstration of co-regulation information technology in food safety governance funded by National Key R&D Program of China (2017YF1602000).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YZ and XL conceived, designed and performed the study and collected the data; ZC conducted the analysis and wrote the manuscript; XX, XL, ZS, XH, MS, CR and YZ helped to revise the manuscript content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This project was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Committee of Chongqing Medical University (Record number: 2015012). Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and they could voluntarily participate or withdraw from the study at any stage.

Consent for publication

All eight authors consent to publish the manuscript.

Competing interests

None.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure 1.

Introduction of “Yingyangren” WeChat official account. Table 1. The questionnaire on effect evaluation of WeChat based intervention on food safety KAP among university students. Table 2. The reading rate of each popular science article released by “Yingyangren” WeChat official account in the intervention group. Table 3. Feedback from reading food safety-related popular science articles released by “Yingyangren” WeChat official account in the intervention group. Table 4. Subjective assessment evaluation with the food safety-related popular science articles released by “Yingyangren” WeChat official account in the intervention group. Table 5. Other ways to obtain food safety-related information among all university students.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Cai, Z., Luo, X., Xu, X. et al. Effect of WeChat-based intervention on food safety knowledge, attitudes and practices among university students in Chongqing, China: a quasi-experimental study. J Health Popul Nutr 42, 28 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41043-023-00360-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41043-023-00360-y