Abstract

Background

Pollen development is an energy-consuming process that particularly occurs during meiosis. Low levels of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) may cause cell death, resulting in CMS (cytoplasmic male sterility). DNA sequence differences in ATP synthase genes have been revealed between the N- and S-cytoplasms in the cotton CMS system. However, very few data are available at the RNA level. In this study, we compared five ATP synthase genes in the H276A, H276B and fertile F1 (H276A/H268) lines using RNA editing, RNA blotting and quantitative real time-PCR (qRT-PCR) to explore their contribution to CMS. A molecular marker for identifying male sterile cytoplasm (MSC) was also developed.

Results

RNA blotting revealed the absence of any novel orf for the ATP synthase gene sequence in the three lines. Forty-one RNA editing sites were identified in the coding sequences. RNA editing showed that proteins had 32.43% higher hydrophobicity and that 39.02% of RNA editing sites had proline converted to leucine. Two new stop codons were detected in atp6 and atp9 by RNA editing. Real-time qRT-PCR data showed that the atp1, atp6, atp8, and atp9 genes had substantially lower expression levels in H276A compared with those in H276B. By contrast, the expression levels of all five genes were increased in F1 (H276A/H268). Moreover, a molecular marker based on a 6-bp deletion upstream of atp8 in H276A was developed to identify male sterile cytoplasm (MSC) in cotton.

Conclusions

Our data substantially contributes to the understanding of the function of ATP synthase genes in cotton CMS. Therefore, we suggest that ATP synthase genes might be an indirect cause of cotton CMS. Further research is needed to investigate the relationship among ATP synthase genes in cotton CMS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cytoplasmic male sterility (CMS) is a universal and maternally inherited phenomenon in which the male reproductive structure fails to develop. The molecular mechanisms of CMS plants have been extensively studied for several decades [1]. To date, the cause of CMS in several types of plants has been demonstrated to be chimeric open reading frames (ORFs) resulting from rearrangements of the mitochondrial genome. These ORFs include urf13 of maize CMS-T [1], orf79 of Boro II rice [2] and pcf of petunia [3]. These ORFs are associated with ATP synthase gene promoter regions or portions of coding regions and inhibit the expression of ATP synthase genes [4]. The ATP synthase complex, composed of five subunits encoded by mitochondrial DNA, converts the electrochemical gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane into ATP for cellular biosynthesis at the terminal step of oxidative phosphorylation [5].

In the cotton CMS system, CMS-D2 and CMS-D8 are derived from the introduction of the cytoplasm of Gossypium harknessii Brandegee (D2) and Gossypium trilobum (DC) Skovst (D8), respectively, into upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum, AD1) [6, 7]. Cotton CMS was identified more than 40 years ago but has not been employed extensively in hybrid breeding as the cytoplasm of wild species has negative effects on cotton yield [8]. Thus, it is imperative to develop a new system of cotton CMS with cytoplasm from cultivated species. In the present study, a new CMS line, H276A, the cytoplasm of which is derived from cultivated species, was investigated. The cytological differences between the CMS lines and their maintainer lines have been explored [9]; however, the molecular mechanism of CMS remains unknown.

RNA editing is a post-transcriptional process that can synthesize different amino acid sequences from genomic sequences by conversion of cytidine (C) to uridine (U). In plant mitochondrial systems, RNA editing plays an important role in gene expression at the RNA level and is a critical process for generating functional proteins [10]. It has been reported that some types of CMS are associated with inadequate or divergent RNA editing of mitochondrial genes. In CMS-S maize, orf77 has a similar sequence to atp9; however, orf77 has less RNA editing relative to atp9. The novel RNA editing of orf77 led to CMS by inhibiting the expression of atp9 [11]. In rice CMS line Yingxiang A, RNA editing caused an amino acid conversion, which produced a non-functional atp9 subunit [12].

In previous studies of cotton CMS, investigations have focused on the mutation of mitochondrial genome sequences and exploration of the molecular markers of male sterility cytoplasm (MSC). RFLP polymorphisms were detected between CMS-D2 and normal AD1 cytoplasm with probes for cox1, cox2, and atp1 [13]. Zhang et al. [14] reported that six genes (atp1, atp9, ccmb, nad6, nad7c and rr18) have RFLPs between P30B and P30A and explored several male sterility cytoplasm markers. In the above studies, several significant RFLPs associated with ATP synthase genes have been revealed between the N- and S-cytoplasm in the cotton CMS system. However, little information is available at the RNA level. In this study, we compared five ATP synthase genes in H276A, H276B and the fertile F1 (H276A/H268) by RNA editing, RNA blotting and qRT-PCR to explore their contribution to CMS. In addition, a molecular marker for identifying MSC was developed.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

For gene cloning, qRT-PCR and RNA blotting, three cotton lines were used: CMS (H276A), a maintainer (H276B) and a fertile F1 (H276A/H268). To identify the cytoplasmic characteristics, 37 varieties of cotton were employed including nine CMS lines (NL11-3A, NL11-4A, NL11-5A, NL11-8A, NL11-9A, NL11-21A, NL11-26A, J-1A, and J-4A) with abortive-type H276A cytoplasm; five CMS lines (NC15-43, NC15-41, NC15-39, NC15-37, and NC15-35) with abortive-type Zhong16A [15] cytoplasm; 14 maintainer lines (NL11-3B, NL11-4B, NL11-5A, H11-8B, NH11-9B, NH11-21B, NL11-26B, J-1B, J-4B, NC15-42, NC15-40, NC15-38, NC15-36, and NC15-34); and nine hybrid F1 lines (NL11-3A/H268, NL11-4/H268, NL11-5A/H268, NL11-8A/H268, NL11-9A/H268, NL11-21A/H268, NL11-26A/H268, J-1A/H268, and J-4A/H268). All plant materials were grown in the experimental field of Guangxi University, China under natural conditions.

Total DNA and RNA extraction

Genomic DNA was extracted from young leaves of each genotype by the CTAB method [16]. Total RNA from anthers at the abortive stage (tetrad stage) was isolated using the Quick RNA Isolation Kit with on-column DNaseI digestion (Huayueyang, China). The integrity and concentration of the nucleic acids were determined using 1% agarose gels and a NanoDrop 2000 (UV spectrometer) (Thermo, USA).

cDNA synthesis, cloning and sequencing

All primers (Additional file 1) used in this study were designed based on the Gossypium hirsutum L. mitochondrial genome (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/JX065074.1). For each sample, 1 μg total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using TransScriptRII One-Step gDNA Removal and cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (Trans, China). Elimination of gDNA was verified with primers for cox2, which amplified a 1887 bp fragment of the gDNA, including a 1494-bp intron, but a 393-bp fragment was amplified for cDNA. For amplification of ATP synthase genes, 50 ng DNA and 0.5 μl cDNA were used as templates. The amplicons were cloned into the PMD-19T simple vector (TAKARA, Japan), then three gDNA positive clones were selected randomly and sequenced [23].

qRT-PCR analysis of ATP synthase genes

Relative quantification of five genes in the three cotton lines were conducted by real-time qRT-PCR analysis with a C1000 TouchTM Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad, USA) with TransStartR Tip Green qPCR SuperMix (Trans, China). A housekee** gene, 18s, served as the internal reference. The 18 s primer sequences were 5′-ACACTTCACCGGACCATTCAAT/5′-CCTGGAAGAACCCTTTGTGA. The qRT-PCR conditions followed the manufacturer’s procedure: 30 s at 95 °C followed by 42 cycles of heating at 95 °C for 5 s and annealing at 60 °C for 30 s, then heating to 95 °C with an increment of 0.5 °C for 5 s to generate the melt curve. The relative expression level was calculated by the 2−∆∆Ct method with three replicates [17].

RNA editing and gene expression data analysis

The percentage of RNA editing efficiency was determined with at least 13 cDNA clones from each of the three materials (CMS, maintainer line and fertility F1) for each gene [23]. For an RNA editing site, at least two C-U conversions at a position should be detectable to be regarded as an authentic RNA editing site [25]. RNA editing sites are classified as “full editing” when ≥ 80% of recovered sequences contain the converted sequence or “partial editing” when < 80% of recovered sequences contain the converted sequence [18].

Northern blot analysis

Approximately 30 μg total RNA was denatured and separated on 1% denaturing formaldehyde agarose gels and transferred to a Hybond N+ nylon membrane (GE, UK). The blots were hybridized with a DIG-high labeled cDNA probe at 42 °C for 12 h, and subsequently the manufacturer’s instructions for the DIG-High prime DNA Labeling and Detection Starter Kit II (Roche, Germany) were followed.

Molecular marker and polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE)

The primer sequences of molecular marker were 5′-TACAGGAAGGACTCGCTTTCTCTTT/5′-AAGGCATAACCAGAAGAATTGTGAA. The PCR conditions for the molecular marker were 3 min at 95 °C followed by 42 cycles of heating at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 56 °C for 30 s and amplification at 72 °C for 30 s, and a final amplification at 72 °C for 5 min. To analyze the PCR product of the molecular marker, 10% native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was used; the 50 ml reagent mix included 12.5 ml 40% polyacrylamide, 40 μl tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED), 5 ml 10 × tris boric acid (TBE), and 400 μl 10% ammonium persulfate (APS), with ddH2O added to 50 ml. The gel was stained by 10% AgNO3 and colored with formaldehyde.

Statistical analysis

Data on gene expression among CMS, maintainer and fertile lines of cotton were statistically analyzed with one-way ANOVA using SPSS 18.0.

Results

Sequence and transcript polymorphisms analysis of five genes

The sequences of five genes (atp1, atp4, atp6, atp8 and atp9) in H276A, H276B and a fertile F1 (H276A/H268) were obtained using homology cloning. Sequences analysis (Additional files 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6) revealed no difference in coding regions between CMS line H276A and its maintainer line H276B, but a one base conversion (C > A) at the 171th base of atp8 resulted in an amino acid change (arginine to serine) at the 56th amino acid. However, a 6-bp deletion in the 5′ flanking region of atp8 and six base conversions in the untranslated regions (UTR) of atp1 were identified in H276A in comparison with H276B. In addition, the fertile F1 (H276A/H268) had sequences similar to CMS line H276A for all five genes.

In the present study, northern blotting was used to explore transcript polymorphisms of ATP synthase genes in three cotton materials. The results showed that only one transcript in atp1, atp4, atp6 and atp9, but two transcripts in atp8 (Fig. 1). All five genes showed similar transcripts in CMS line H276A, maintainer line H276B and the fertile F1 (H276A/H268). To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to analyze the transcripts of five ATP synthase genes in cotton.

RNA editing of five ATP synthase genes

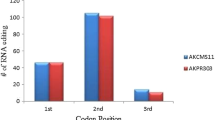

The features and editing frequencies of each editing site of five genes (atp1, atp4, atp6, atp8 and atp9) were detected by sequence cloning (Table 1). A total of 41 editing sites, containing 27 full and 14 partial editing sites, were identified in coding regions. RNA editing results showed that 90.3% of amino acids were changed, and silent RNA editing contributed to 9.75% of the changes. The highest frequencies of amino acid changes were proline (P) > leucine (L) (39.02%), followed by serine (S) > leucine (L) (19.51%), and phenylalanine (F) > phenylalanine (F) (7.32%) (Fig. 2). Amino acid changes led to increased hydrophobic amino acids as described in plant organelles [19]. The frequency of RNA editing sites that resulted in the change from one hydrophobic amino acid to another was 56%. Further, the frequency of hydrophilic to hydrophobic changes was 27%, and a small percentage of changes (4.8%) resulted in hydrophobic to hydrophilic changes. No variation was observed in hydrophilic to hydrophilic amino acid changes (Table 2). The position of RNA editing was mostly at the 2nd codon base (58.54%), which was consistent with findings for Arabidopsis thaliana [20], and RNA editing at the 1st and 3rd codon bases was 26.83% and 14.63%, respectively.

atp1, atp8

Six and four full editing sites were detected in atp1 and atp8, respectively. However, there was no significant difference noted at any of these sites between CMS line H276A and its maintainer line H276B.

atp4

Twelve editing sites (ten full editing and two partial editing) were identified in atp4. The editing frequency of the 225th base, which was located at the 3rd codon base of the 74th amino acid, decreased significantly in H276A. However, the 2nd codon base of the 74th amino acid was a full editing site and had a similar amino acid change (proline to leucine). The editing frequency of the other partial editing site at the 247th base was significantly increased in H276A compared with that of H276B (50% vs. 27.2%).

atp6

A total of eleven partial editing sites were identified in atp6. A partial editing site at the 787th base caused a change from glutamine to a stop codon, and the frequency of editing was 63.6% and 45.5% in CMS and the maintainer line, respectively. A novel stop codon was created in the 789 bp coding region though the 816 bp coding region in the wild-type. At the other special editing site at the 294th base, the maintainer line had a significantly higher RNA editing efficiency compared with the CMS line (18.2% vs. 0%).

atp9

Seven full and one partial editing site were found in atp9. However, a new stop codon with a similar editing frequency between H276A and H276B was detected. The partial editing site (the 243th base), which had a substantially decreased editing frequency in H276A, was a silent RNA editing site (F > F).

In addition, comparative analysis of the RNA editing frequency between CMS line H276A and the fertile F1(H276A/H268) indicated that, except for atp4 (225th base), atp6 (331th base) and atp8 (77th base), all other RNA editing sites in the F1 had a relatively higher editing efficiency compared with H276A. An increased editing efficiency may be associated with the presence of the restorer gene.

Relative expression of five genes in anthers of three materials

The relative expression levels of five ATP synthase genes in H276A, H276B and a hybrid F1 (H276A/H268) were detected using real-time qRT-PCR. Data were analyzed using SPSS software. The results showed a substantial reduction in the expression levels of atp1 (0.70), atp6 (0.70), atp8 (0.59), and atp9 (0.61) compared with H276B (P < 0.05). By contrast, a significant increase in the expression levels of atp1 (1.25), atp4 (2.06), atp6 (1.64), atp8 (1.55) and atp9 (2.27) in the F1(H276A/H268) relative to the maintainer line H276B (P < 0.01) was observed (Fig. 3).

Expression analysis of five genes in cotton anthers by qRT-PCR. The housekee** gene 18S was used as an internal control; H276A, CMS line; H276B, maintainer line; and H276A/H268, F1 plants from the descendant of restorer H268 hybridized with H276A. Error bars represent standard deviation (n = 3). Double asterisk represents significance at 1% probability

Development of a molecular marker to identify MSC based on atp8

To identify MSC in cotton, a molecular marker based on the 6 bp deletion at the 5′ flanking region of atp8 in CMS line H276A was developed. The product of special primers BQatp8-F and BQatp8-R was 123 bp and 129 bp in MSC and MFC, respectively, as shown in S.5. Nine cotton CMS lines with abortive type H276A cytoplasm, their maintainer lines and the hybrid F1 were used to detect the accuracy of the molecular marker. A 123 bp fragment was amplified from all CMS lines and their hybrid F1 compared to a 129 bp fragment from their maintainer lines (Fig. 4). The results indicated that the molecular marker could be used to identify MSC in cotton. To extend this observation, five CMS lines with abortive type Zhong16A and their maintainer lines were analyzed, which showed that all CMS lines and all maintainer lines had the same band as in the corresponding CMS line H276A and maintainer line H276B (Additional file 7).

Identification accuracy of the molecular marker. M:10 bp DNA ladder; Lane 1–15: NL11-3A, NL11-3B, NL11-3A/H268, NL11-4A, NL11-4B, NL11-4A/H268, NL11-5A, NL11-5B, NL11-5A/H268, NL11-8A, NL11-8B, NL11-8A/H268, NL11-9A, NL11-9B, and NL11-9A/H268; Lane 16–30: NL11-21A, NL11-21B, NL11-21A/H268, J-1A, J-1B, J-1A/H268, J-4A, J-4B, J-4/H268, NL11-26A, NL11-26B, NL11-26A/H268, H276A, H276B, and H276A/H268

Discussion

Although there have been consistent findings for ATP synthase genes and CMS in other cotton CMS systems, further research is needed for detailed understanding of the molecular mechanisms of ATP synthase genes at the transcriptional level. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to detect CMS-associated genes in cotton using RNA blots. This strategy has been used to identify some critical CMS genes, such as WA352 in rice [21] and orf456 in chili pepper [22]. However, our data demonstrated that there was an absence of novel orf containing the ATP synthase gene sequence in the CMS line compared with the other two materials.

To gain a detailed understanding of transcription of ATP synthase genes, we investigated their RNA editing, and 41 RNA editing sites were identified. All editing sites had a change from C to U, which corresponds with the observations from rice [23] and CMS-D8 [24]. In other cotton CMS systems with RNA editing sites, there was strong specificity. For instance, atp1, atp4, atp6, atp8 and atp9 of CMS-D8 [24] have 7, 9, 15, 2, and 2 editing sites, respectively. However, our study found atp1, atp4, atp6, atp8 and atp9 have 6, 12, 11, 4, and 9 RNA editing sites, respectively.

The relationship between CMS and mitochondrial genome RNA editing has been widely studied. Previous studies suggested that silent editing can interrupt normal function and can alter secondary structure of RNA [25]. In the present study, four silent editing sites (three F > F and one P > P) were detected in three materials with similar editing frequencies. In addition, RNA editing may produce a new stop codon that creates a truncated open reading frame. For instance, wheat CMS resulted from novel RNA editing at the 37th base of atp9 creating a stop codon [10]. In the present study, two new stop codons from RNA editing were identified. Of these, one was located at 223th base of atp9, which had not been previously reported in cotton, but no difference existed in the editing frequency of all three materials. The other stop codon was at the 787th base of atp6, and its editing frequency increased with fertile recovery. Except for the editing sites located at the 225th base of atp4 and the 76th and 77th bases of atp6, the frequencies of the remaining RNA editing sites increased in the hybrid F1relative to those of H276A. We inferred that it has its own restorer gene. Most restorer genes encode a PPR protein, which is essential for RNA editing of mitochondrial genes [25].

Pollen development is an energy-consuming process, especially during meiosis, and cell death might be caused by low levels of ATP leading to CMS [26]. qRT-PCR of five ATP synthase genes of anthers at the tetrad stage showed that except for atp4, the other four genes had remarkably lower expression in H276A; by contrast, all five genes in the hybrid F1 (H276A/H268) were increased dramatically. These results were consistent with atp8 and atp9 in kenaf [27, 28], which suggested that restorer genes affect ATP synthase expression. Moreover, these results also suggested that cotton CMS could be associated with decreased expression of ATP synthase genes (atp1, atp6, atp8 and atp9). However, the relationship between cotton CMS and ATP synthase genes needs further investigation.

Molecular markers have become an important and more convenient tool for identification of MSC in comparison to traditional breeding. In cotton breeding, a shortage of CMS prevented the utilization of cotton heterosis. To overcome this problem, cotton MSC molecular markers were explored based on different sequences. However, to date, all MSC molecules based on PCR were based on mutations around atp1, such as scar611 [29] and ssr160 [14].

Conclusion

We identified no novel orf in ATP synthase gene sequences in three cotton lines and 41 RNA editing sites in coding sequences. The result of RNA editing in three materials indicated that no differences were associated with CMS. However, the results of qRT-PCR suggested that ATP synthase genes may be an indirect cause of cotton CMS. The relationship between ATP synthase genes and cotton CMS needs further study.

Abbreviations

- CMS:

-

cytoplasmic male sterility

- qRT:

-

quantitative reverse transcribed PCR

- ATP:

-

adenosine triphosphate

- ORFs:

-

open reading frames

- MSC:

-

male sterility cytoplasm

- MFC:

-

male fertility cytoplasm

References

Dewey RE, Levings CS 3rd, Timothy DH. Novel recombinations in the maize mitochondrial genome produce a unique transcriptional unit in the Texas male-sterile cytoplasm. Cell. 1986;44(3):439–49.

Wang ZH, Zou YJ, Li XY, et al. Cytoplasmic male sterility of rice with boro II cytoplasm is caused by a cytotoxic peptide and is restored by two related PPR motif genes via distinct modes of mRNA silencing. Plant Cell. 2006;18(3):676–87. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.105.038240.

Pruitt KD, Hanson MR. Splicing of the Petunia cytochrome oxidase subunit II intron. Curr Genet. 1991;19(3):191–7.

Hanson MR, Bentolila S. Interactions of mitochondrial and nuclear genes that affect male gametophyte development. Plant Cell. 2004;16:S154–69. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.015966.

Millar AH, Whelan J, Soole KL, et al. Organization and regulation of mitochondrial respiration in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2011;62:79–104. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103857.

Meyer VG. Male sterility from Gossypium harknessii. J Heredity. 1975;1:1.

MSJ. A new male sterility from G. trilobum. In: Proceedings of Beltwide Cotton Conf. 1992.

Li Y, Wang X, Xu Y. Cytological observation of cytoplasmic male-sterile anthers of brown cotton. J Zhengjiang Univ. 2002;28(1):11–5. https://doi.org/10.3321/j.ssn:1008-9209.2002.01.005.

Kong X, Liu D, Liao X, et al. Comparative analysis of the cytology and transcriptomes of the cytoplasmic male sterility line H276A and its maintainer line H276B of cotton (Gossypium barbadense L.). Int J Mol Sci. 2017. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18112240.

Nowak C, Kuck U. RNA editing of the mitochondrial atp9 transcript from wheat. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18(23):7164.

Gallagher LJ, Betz SK, Chase CD. Mitochondrial RNA editing truncates a chimeric open reading frame associated with S male-sterility in maize. Curr Genet. 2002;42(3):179–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00294-002-0344-5.

Wei L, Yan ZX, Ding Y. Mitochondrial RNA editing of F0-ATPase subunit 9 gene (atp9) transcripts of Yunnan purple rice cytoplasmic male sterile line and its maintainer line. Acta Physiol Plant. 2008;30(5):657–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11738-008-0162-6.

Wang F, Feng CD, O’Connell MA, et al. RFLP analysis of mitochondrial DNA in two cytoplasmic male sterility systems (CMS-D2 and CMS-D8) of cotton. Euphytica. 2010;172(1):93–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10681-009-0055-9.

Zhang X, Meng ZG, Zhou T, et al. Mitochondrial SCAR and SSR Markers for distinguishing cytoplasmic male sterile lines from their isogenic maintainer lines in cotton. Plant Breed. 2012;131(4):563–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0523.2012.01971.x.

Ming T. Morphology, cytology and molecular identification of the hybrid from Zhongmiansuo 16. Guangxi: Guangxi University; 2014.

Zhang J, Stewart JM. Economical and rapid method for extracting cotton genomic DNA. J Cotton Sci. 2000;4(3):193–201.

Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C (T)) method. Methods 2001;25:402–408. https://doi.org/10.1006/meth.2001.1262.

Mower JP, Palmer JD. Patterns of partial RNA editing in mitochondrial genes of Beta vulgaris. Mol Genet Genomics. 2006;276(3):285–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00438-006-0139-3.

Yura K, Go M. Correlation between amino acid residues converted by RNA editing and functional residues in protein three-dimensional structures in plant organelles. BMC Plant Biol. 2008;1:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2229-8-79.

Giege P, Brennicke A. RNA editing in Arabidopsis mitochondria effects 441 C to U changes in ORFs. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(26):15324–9.

Luo DP, Xu H, Liu ZL, et al. A detrimental mitochondrial-nuclear interaction causes cytoplasmic male sterility in rice. Nat Genet. 2013;45(5):573. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2570.

Kim DH, Kang JG, Kim BD. Isolation and characterization of the cytoplasmic male sterility-associated orf456 gene of chili pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Plant Mol Biol. 2007;63(4):519–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11103-006-9106-y.

Hu JH, Yi R, Zhang HY, et al. Nucleo-cytoplasmic interactions affect RNA editing of cox2, atp6 and atp9 in alloplasmic male-sterile rice (Oryza sativa L.) lines. Mitochondrion. 2013;13(2):87–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mito.2013.01.011.

Suzuki H, Yu JW, Ness SA, et al. RNA editing events in mitochondrial genes by ultra-deep sequencing methods: a comparison of cytoplasmic male sterile, fertile and restored genotypes in cotton. Mol Genet Genomics. 2013;288(9):445–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00438-013-0764-6.

Wang J, Cao MJ, Pan GT, et al. RNA editing of mitochondrial functional genes atp6 and cox2 in maize (Zea mays L.). Mitochondrion. 2009;9(5):364–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mito.2009.07.005.

Chen P, Ran SM, Li R, et al. Transcriptome de novo assembly and differentially expressed genes related to cytoplasmic male sterility in kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus L.). Mol Breed. 2014;34(4):1879–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11032-014-0146-8.

Liao XF, Zhao YH, Chen P, et al. A comparative analysis of the atp8 gene between a cytoplasmic male sterile line and its maintainer and further development of a molecular marker specific to male sterile cytoplasm in Kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus L.). Plant Mol Biol Rep. 2016;34(1):29–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s1110.

Zhao Y, Chen P, Liao X, et al. A comparative study of the atp9 gene between a cytoplasmic male sterile line and its maintainer line and further development of a molecular marker specific for male sterile cytoplasm in kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus L.). Mol Breed. 2013;32(4):969–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11032-013-9926-9.

Wu JY, Gong YC, Cui MH, et al. Molecular characterization of cytoplasmic male sterility conditioned by Gossypium harknessii cytoplasm (CMS-D2) in upland cotton. Euphytica. 2011;181(1):17–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10681-011-0357-6.

Authors’ contributions

RZ conceived, designed and supervised the study. XK and DL performed the experiments and drafted the manuscript. JZ, YD and BL participated in the experiments. AK revised the manuscript and inserted useful suggestion. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31360348). Authors are thankful for the financial support from Mr. Hong-Wu Weng original research foundation in Peking University of China.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of supporting data

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

We are thankful the National Natural Foundation of China for their financial support.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1.

Primers used in this study.

Additional file 2.

Sequences analysis of atp1 in three materials.

Additional file 3.

Sequences analysis of atp4 in three materials.

Additional file 4.

Sequences analysis of atp6 in three materials.

Additional file 5.

Sequences analysis of atp8 in three materials.

Additional file 6.

Sequences analysis of atp9 in three materials.

Additional file 7.

Amplification of molecular marker specific to MSC.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kong, X., Liu, D., Zheng, J. et al. RNA editing analysis of ATP synthase genes in the cotton cytoplasmic male sterile line H276A. Biol Res 52, 6 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40659-019-0212-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40659-019-0212-0