Abstract

Drift rate is a very important parameter in the evolution of stock price, which has significant impact on the corresponding option pricing. This paper deals with an inverse problem of recovering the drift function by current market prices of options. Different from the usual inverse volatility problem, our mathematical model does not tend to zero at infinity, which may bring great trouble to theoretical analysis and numerical calculation. To overcome this difficulty, we use an artificial boundary and homogenization technique to transform the original problem into a homogeneous initial boundary value problem on a bounded domain. Then, based on the optimal control framework, we construct the corresponding optimization problem and strictly prove the well-posedness of the minimizer. Finally, we design an iterative algorithm to obtain the numerical solution. We give some typical examples to verify the validity of our method.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Motivated by the need of modeling and market forecasting, inverse problems in financial mathematics have received considerable attention (see [1, 2, 7, 14–16, 19–21, 23, 26, 30]).

In general, the underlying asset \(S_{t}\) at time t is modeled by the stochastic differential equation

where the process \(W_{t}\) is the standard Brownian motion. The parameters μ and σ are called the real drift and local volatility of the underlying asset, respectively. The drift term μ indicates the expected return of stock price changes, whereas the volatility is used to measure the variability of variables. The stock price movement is determined by the drift rate, volatility, and Brownian motion. The randomness of volatility, drift rate, and Brownian motion determines the process of stock price, which is full of randomness and uncertainty. In practice, the drift rate is quite difficult to measure, but it has an important impact on the stock price trend. Therefore it is of great financial significance to use some indirect approaches to estimate the drift rate, which represents people’s prediction of the expected return rate of stock price.

Black and Scholes [1] first discovered how to construct a dynamic portfolio \(\Pi _{t}\) of a derivative security and the underlying asset. By Itô’s lemma the stochastic behavior of the derivative security \(u(t,S)\) is driven by the stochastic differential equation

In the absence of arbitrage opportunities, the instantaneous return of this portfolio must be equal to the interest rate \(r>0\), that is, the return of a riskless asset such as a bank deposit. Therefore this equality takes the form of the following partial differential equation (the Black–Scholes equation):

where r and the dividend rate δ are known constants.

However, the theoretical prices of options with different strike prices calculated by the Black–Scholes model differ from real market prices. Under the noarbitrage property of the financial market, the real drift μ does not enter the above equation. In [23], taking this into account, the following new binary option model is derived:

This model is a form of arbitrage model. Further, considering the property of binary option, the final condition at the maturity is specified by

We would like to determine the drift function μ using the current market prices

of options with different strikes K and fixed maturity T.

Using the Dupire technique, we deduce that the price \(u(T,K)\) of the binary option with maturity T and strike price K satisfies the adjoint equation:

Making the changes in variables \(\bar{W}(\tau ,y)=u(T,K)\), \(y=\ln (K/S^{*})\), \(\tau =T-t\), we identify the drift \(a(y):=\mu (K)\) satisfying the following:

Problem P1

The Cauchy problem of second-order parabolic equation

where the local volatility \(\sigma _{0}\) is a constant, \(a(y)\) is an unknown coefficient in (1.2). The extra condition (1.1) is transformed into

Determine the functions W̄ and \(a(y)\) satisfying (1.2)–(1.3).

In this problem, \(y\in R\), so the problem is an unbounded domain problem which is not conducive to numerical calculations. With this in mind, we translate the problem into an approximation problem on a larger bounded domain \(y\in [-L,L]\), where L is a large positive constant. The problem can be rewritten in the following form.

Problem P2

The initial-boundary value problem of the second-order parabolic equation

and the extra condition

Determine the functions W and \(a(y)\) satisfying (1.4)–(1.5).

The boundary conditions in P2 is nonhomogeneous, which is not conductive to integration by parts. We try to convert the nonhomogeneous equation to a homogeneous one. Let

Then Problem P2 is transformed into the following form.

Problem P

The initial-boundary value problem of second-order parabolic equation

The additional condition is given by

Inverse coefficient problems for parabolic equations are well studied in the literature, and abundant theoretical and numerical results are obtained. The inverse problem of identifying coefficient \(q(y)\) in the parabolic equation

from final overdetermination data \(u(y,T)\) has been investigated by several authors, for example, in [5, 6, 17, 18, 25, 27, 29, 31]. The purely time-dependent case, that is, determining the unknown radiative coefficient in heat conduction equations independent of the spatial variable, has been extensively studied by several authors (see, e.g., [3, 4, 8–11, 24, 28]). For the space- and time-dependent case, we refer the readers to [12, 13].

In financial mathematics, there is often a kind of inverse problems of using market observation data to reconstruct the implied volatility. Using the optimal control theory, the recovery of volatility in the Black–Scholes equation

is studied from the current options market in [21]. In [2] the authors reduce the identification of volatility to an inverse parabolic problem with terminal observation and establish uniqueness and stability results by using the Carleman estimates. In [7] the local volatility surface is recovered by nonlinear Landweber iteration using simulated data. A new continuous-time model is proposed in [19] to recover the volatility, and the corresponding numerical results are obtained by solving a couple of fully nonlinear parabolic equations. In [16] the volatility is parameterized by five special numbers, and (nonlinear) minimization of the mismatch functional is implemented.

Compared with the inverse volatility problem, there are few documents on the inverse problem of drift rate. In [23] the authors consider an inverse problem of recovering the real drift of binary call options from market prices. By using the linearization method the inverse problem is transformed to an integral equation, and numerical results are also obtained.

In this paper, we use the optimal control method to discuss Problem P. Compared with other papers concerning volatility identification problems, our work has the following unusual features. First, the unknown function to be identified is the first-order derivative coefficient rather than the principal one. Second, our mathematical model does not tend to zero at infinity, which may bring great trouble to theoretical analysis and numerical calculation.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Sects. 2 and 3, we transform Problem P into an optimal control Problem P3 and prove the existence of the minimum for the control functional. The necessary condition, which must be satisfied by the minimum, is deduced in Sect. 4. In Sect. 5, we prove that the minimum is locally unique under some assumptions. In Sect. 6, we design an iterative algorithm to obtain the numerical solution and give some typical examples. Section 7 ends this paper with a summary.

2 Optimal control problem

Consider the following optimal control problem.

Problem P3

Find \(\bar{a}(y)\in \mathcal{A}\) such that

where

\(U(y,\tau ;a)\) is the solution to problem (1.6) for given \(a\in \mathcal{A}\), and N is the regularization parameter.

For given \(a\in \mathcal{A}\), from Sobolev’s embedding theorem we have \(a\in C^{1/2}(-L,L)\) and \(\|a\|_{C^{1/2}(-L,L)}\leq C\) (here C is a constant). The known Schauder theory for parabolic equations (see [22]) guarantees that there is a unique solution \(U(y,\tau )\in C^{2+\alpha ,1+\alpha /2}(\bar{Q})\) to the initial-boundary value problem (1.6).

Lemma 2.1

If \(U(y,\tau )\) is a solution to the initial-boundary value problem (1.6), then

where \(Q_{\tau }=(-L,L)\times (0,\tau ]\), and C is a constant.

Proof

From equation (1.6) we have

Integrating by parts, we obtain

From the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality we have

that is,

From Gronwall’s inequality we have

This completes the proof of Lemma 2.1. □

3 Existence

Theorem 3.1

There exists a minimizer \(\bar{a}\in \mathcal{A}\) of \(J(a)\), that is,

Proof

Let \((U_{n},a_{n})\) be a minimizing sequence. Since \(J(a_{n})\leq C\), thanks to the particular structure of J, we deduce

By the Sobolev imbedding theorem we obtain

Thus

Therefore we can select subsequences of \(a_{n}\) and \(U_{n}\), again denoted by \(a_{n}\) and \(U_{n}\), such that

We easily check that \((\bar{a}(y),\bar{U}(y,\tau ))\) satisfies (1.6). By the Lebesgue control convergence theorem and the weak semicontinuity of the \(L^{2}\) norm we obtain

Hence

This completes the proof of Theorem 3.1. □

4 Necessary condition

Theorem 4.1

Let a be the solution of the optimal control problem (2.1). Then there exists a triple of functions \((U,V;a)\) satisfying the following system:

and

for all \(h\in \mathcal{A}\).

Proof

For any \(h\in \mathcal{A}\) and \(0\leq \delta \leq 1\), we have

Let \(U_{\delta }\) be the solution to the initial-boundary value problem (4.1) with given \(a=a_{\delta }\). Since a is an optimal solution, by (2.2) we have

Denoting \(U^{\prime }_{\delta }\equiv \frac{\partial U_{\delta }}{\partial \delta }\) and using (4.1), by direct calculation we get the following equation:

Let \(\xi =U^{\prime }_{\delta } |_{\delta =0}\). Then ξ satisfies

From (4.4) we have

Suppose V is the generalized solution of the following adjoint problem:

Combining (4.7) and (4.9), we easily obtain that

This completes the proof of Theorem 4.1. □

5 Uniqueness

Lemma 5.1

For any bounded continuous function \(f(y)\in C[-L,L]\), we have

where \(y_{0}\) is a fixed point.

Proof

This completes the proof of Lemma 5.1. □

Let \(a_{1}(y)\) and \(a_{2}(y)\) be two minimizers of the control Problem P3, and let \(\{U_{i},V_{i}\}\) (\(i=1,2\)) be solutions of system (4.1)–(4.2) in which \(\bar{a}=a_{i}\), respectively. Set

Then U and V satisfy

and

Lemma 5.2

Proof

Set \(t=\tau ^{*}-\tau \). Then from (4.2) we have

Letting \(W=\|U_{i}(y,\tau ^{*})-U_{i}^{*}(y)\|_{\infty }\pm V_{i}\), we obtain

Using the maximum principle, we obtain \(\|V_{i}\|_{\infty }\leq \|U_{i}(y,\tau ^{*})-U_{i}^{*}(y)\|_{\infty }\) (\(i=1,2\)).

This completes the proof of Lemma 5.2. □

Lemma 5.3

For problem (5.1) we have the estimates

and

where C is a constant.

Proof

The proof of estimate (5.4) is standard. So we only need to prove estimate (5.5).

From equation (5.1) we have, for \(0\leq \tau \leq \tau ^{*}\),

Using the boundedness of \(a_{1}(y)\), we get the following inequality:

that is,

From Gronwall’s inequality we have

This completes the proof of Lemma 5.3. □

Lemma 5.4

For problem (5.2) we have the estimate

where C is a constant.

Proof

From equation (5.2) we have

By Lemma 5.3 this yields

From Gronwall’s inequality we have

This completes the proof of Lemma 5.4. □

Theorem 5.5

Let \(a_{1}(y)\) and \(a_{2}(y)\) be two minimizers of the optimal control Problem P3. If there exists a point \(y_{0}\) such that

then for \(\tau ^{*}\ll 1\), we have

Proof

Taking \(h=a_{2}\) when \(\bar{a}=a_{1}\) and \(h=a_{1}\) when \(\bar{a}=a_{2}\) in (4.3), we have

where \(\{U_{i},V_{i}\}\) (\(i=1,2\)) are solutions of system (4.1)–(4.2) with \(\bar{a}=a_{i}\) (\(i=1,2\)), respectively. From (5.7) and (5.8) we have

By Lemma 5.3, Lemma 5.4, and (5.9) we have

From Lemma 2.1 we have

From Lemma 5.2 we have

By the assumption of Theorem 5.5 there exists a point \(y_{0}\in [-L,L]\) such that

From Lemma 5.1 we have

Then choosing \(\tau ^{*}\ll 1\) such that

we have

Therefore

From the assumption \(A(y_{0})=0\) we have

This completes the proof of Theorem 5.5. □

6 Numerical examples

In this section, we give some numerical examples to test the validity of the proposed methods for reconstruction of the drift. In this paper, we consider the gradient iteration algorithm to obtain the numerical solutions. The key ingredient of this iteration algorithm is the Gâteaux derivative of \(J'(a)\), which is given as follows.

Theorem 6.1

The Gâteaux derivative of \(J'(a)\) at a point \(a\in \mathcal{A}\) along direction \(p(y)\) is determined as

where \(W(y,\tau ;a)\) is the solution of system (1.4) with given coefficient of \(a(x)\in \mathcal{A}\), and \(w(y,\tau ;a)\) satisfies the following equation:

The proof is similar to that of Theorem 4.1.

Remark 6.1

The main difference between Problems P2 and P is the boundary condition. Problem P is homogeneous, whereas Problem P2 is nonhomogeneous. Problem P is convenient for theoretical analysis, such as integration by parts, but there is no difference between the two problems in calculation. In this section, we use Eq. (1.4) as a mathematical model of the forward problem.

Suppose the computational domain \(\bar{Q}=[-L,L]\times [0,\tau ^{*}]\) is divided into a \(2M\times P\) mesh with spatial step size \(h=\frac{L}{M}\) in y direction and the time step size \(\tau =\frac{\tau ^{*}}{P}\), respectively. Grid points \((y_{j},t_{n})\) are defined by

where M and P are two integers.

Based on the above analysis, the detailed procedure of iteration algorithm can be summarized as follows:

Step 1. Choose an initial value of iteration \(a=a_{0}(y)\).

Step 2. Solve the initial-boundary value problem (1.4) to get the solution \(W_{0}(y,\tau )\), where \(a(y)=a_{0}(y)\).

Step 3. Solve Eq. (6.1) to obtain the solution \(w_{0}(y, \tau )\), where \(w_{0}(y, \tau ^{*})=W_{0}(y,\tau ^{*})-W^{*}(y)\).

Step 4. Compute the Gâteaux derivative \(J'(a)\psi _{j}=c_{j}\) for \(j=0,1,2,\ldots ,2M\),

where the functions \(\psi _{j}\) are taken as the base function under current grid:

Then the iteration direction from the jth step to the \((j+1)\)th step is given by

Step 5. Compute the norm of \(C_{0}(y)\) at the jth step:

where h is the spatial step size.

Step 6. Choose an arbitrary small positive constant ε as the stop** parameter. Go on or stop the iteration is determined by the following steps:

Step 6.1. Let \(k=1\).

Step 6.2. Compute \(\mathrm{err}:=J[a_{0}(y)+kC_{0}(y)]-J(a_{0}(y))+ \frac{1}{2}ke^{2}\).

Step 6.3. Compare it with 0; if \(\mathrm{err}\leq 0\), then go to Step 6.4; Otherwise, let \(k\doteq \mu k\) and go to Step 6.2, where μ is an adjusting parameter.

Step 6.4. Take \(a_{1}(y)=a_{0}(y)+kC_{0}(y)\); if \(\|kC_{0}(y)\|\leq \varepsilon \), then exit and stop the iteration scheme. Otherwise, set \(j=j+1\) and go to Step 2. Let \(a_{1}(y)\) be the new initial value of iteration and go on computing by the induction rules until the iterations meet the termination conditions.

We have performed three numerical experiments to check the stability of our iteration algorithm. Since real-world data are not available, we would like to use artificial data to test the stability of the proposed numerical algorithm, that is, the extra condition is obtained by solving the direct problem. In all experiments, we used the basic parameters

Equation (1.4) is solved by the classical finite difference method, the Crank–Nicolson difference scheme:

The discrete equations of the initial boundary value are

The difference scheme is absolutely stable, and its truncation error is \(O(\tau ^{2}+h^{2})\).

Example 1

In the first numerical experiment, we take

and

The spatial and time step sizes are taken as

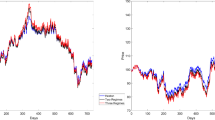

The exact solution and the reconstruction results for different time (denoted by \(\tau ^{*}\)) are shown in Fig. 1. The initial guess is taken to be 0.5. We can see that the drift coefficient \(a(y)\) is well recovered after 260 iterations. The iterative procedure converges quickly, and the effect is satisfactory. However, since \(a(y)\) is a segmented function, the values on the right boundary are quite difficult to reconstruct well. The algorithm converges rather slowly near the right boundary. Also, since the prices near the strike are the most interesting for practitioners, we investigate the recovered function around \(y=0\) (\(S=K\)), where we use three different observation times \(\tau ^{*}= 0.5\), 0.8, and 1. From the figure we observe that the reconstruction is numerically good when \(\tau ^{*}=1\). For all times \(\tau ^{*}\), the reconstructed \(a(y)\) is near-perfect on interval \(y\in (0, 2)\), as shown in Fig. 1.

Identified drifts for Example 1

Example 2

In the second numerical experiment, we take

where L, h, τ are the same as in the first experiment.

The exact solution and the reconstruction results for different iteration times are given in Figs. 2 and 3, where the corresponding iteration numbers are 300 and 380, respectively. The initial guess is taken to be 0. We only needed 380 iterations to achieve a satisfactory result. From the figure we observe that the reconstruction is numerically near-perfect when \(\tau ^{*}=0.5\). The iterative procedure converges quickly and the reconstruction solution seems to be very satisfactory. Since the function \(a(y)\) changes drastically around zero, it is quite difficult to guarantee the convergence at this point. In fact, this form of a function has a larger fluctuation, which also shows that the drift function changes more violently in the real market. However, our algorithm still performs well, and the shape reconstruction of cusp is very good. In the experiment, we find that 400 iterations are not as good as 380 iterations. Since the observation data contains error, which comes from the calculation of forward problem, to obtain stable numerical results, we will cease the iteration at some suitable time.

Identified drifts for Example 2 (iterative number 300)

Identified drifts for Example 2 (iterative number 380)

Example 3

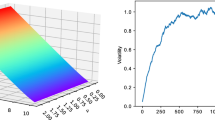

In the third numerical experiment, we take

where L, h, τ are the same as in the first experiment. The numerical results for exact input data can be seen in Fig. 4.

Noiseless case for Example 3

To investigate the stability of the numerical solution, we employ the following noisy data:

with \(\delta =0.001\) and \(\delta =0.01\). The reconstructed results are shown in Figs. 5 and 6. From these two figures we can see that the reconstruction of \(a(y)\) with the noisy data is also satisfactory. Like in Fig. 1, for all times \(\tau ^{*}\), the reconstructed \(a(y)\) is near-perfect on the interval \(y\in (0, 2)\).

Identified drifts with the noisy level 0.001 for Example 3

Identified drifts with the noisy level 0.01 for Example 3

From Fig. 5 we observe that the reconstruction of the 0.1% relative random noise data is almost identical to the reconstruction using noiseless data shown in Fig. 4. From Fig. 6 we observe that the reconstruction of the 1% relative random noise data has a noticeable gap when compared to the reconstruction of the noiseless data. We can see that the reconstruction of the 1% has an upward trend. Nonetheless, even in this case, the form of the reconstruction of the noiseless data is maintained, and we think that changes depend on the size of the error (i.e., noise).

From the above results we conclude that our numerical algorithm for reconstructing trend coefficients is indeed stable for data containing 0.1% and 1% relative random noise data.

Remark 6.2

The parameters of numerical examples are taken as \(r=0.5\) and \(\sigma _{0}=1\). However, in the real market, the range of volatility is usually \([0.2,0.8]\), and the risk-free interest rate r hardly reaches 0.5. So, to better adapt to the real market, we consider the more suitable parameters \(r=0.09\) and \(\sigma _{0}=0.5\). Moreover, to observe the effect of \(\tau ^{*}\) on the reconstruction process, we also consider different values of \(\tau ^{*}\). The numerical results are shown in Fig. 7. We can see that our algorithm still performs well for different parameters r, σ, and \(\tau ^{*}\), and the simulated drift rate is in good agreement with the real one.

Noiseless case for Example 3, where \(r=0.09\) and \(\sigma =0.5\)

7 Concluding remarks

In this paper, we discuss an inverse problem of reconstructing the drift rate coefficient of stock index options using market observation data. Considering the boundlessness and nonhomogeneity of the original model, we use the artificial boundary method and homogenization technique to transform the original problem into a terminal control problem of homogeneous initial-boundary value equation on a bounded domain. We strictly prove the well-posedness of the minimizer of the control problem and give an iterative calculation scheme. Numerical results show that our algorithm is fast and robust.

This paper focuses on the reconstruction of the drift coefficient. To simplify the problem, we assume that the volatility is constant. This assumption usually does not hold in practice. Therefore an interesting question is what conditions need to be imposed to reconstruct the volatility and drift rate simultaneously, which is also the future work for our research.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this paper.

References

Black, F., Scholes, M.: The pricing of options and corporate liabilities. Polit. Econ. 3, 637–654 (1973)

Bouchouev, I., Isakov, V.: The inverse problem of option pricing. Inverse Probl. 5, 7–11 (1997)

Cannon, J.R., Lin, Y.: An inverse problem of finding a parameter in a semilinear heat equation. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 145, 470–484 (1990)

Cannon, J.R., Lin, Y., Xu, S.: Numerical procedure for the determination of an unknown coefficient in semilinear parabolic partial differential equations. Inverse Probl. 10, 227–243 (1994)

Chen, Q., Liu, J.J.: Solving an inverse parabolic problem by optimization from final measurement data. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 1, 183–203 (2006)

Choulli, M., Yamamoto, M.: Generic well-posedness of an inverse parabolic problem – the Hölder space approach. Inverse Probl. 3, 195–205 (1996)

De Cezaro, A., Zubelli, J.: The tangential cone condition for the iterative calibration of local volatility surfaces. IMA J. Appl. Math. 1, 212–232 (2013)

Dehghan, M.: An inverse problems of finding a source parameter in a semilinear parabolic equation. Appl. Math. Model. 25, 743–754 (2001)

Dehghan, M.: Finding a control parameter in one-dimensional parabolic equation. Appl. Math. Comput. 135, 491–503 (2003)

Dehghan, M.: Parameter determination in a partial differential equation from the overspecified data. Math. Comput. Model. 41, 196–213 (2005)

Dehghan, M., Tatari, M.: Determination of a control parameter in a one-dimensional parabolic equation using the method of radial basis functions. Math. Comput. Model. 44, 1160–1168 (2006)

Deng, Z.C., Yang, L., Yu, J.N., Luo, G.W.: Identifying the radiative coefficient of an evolutional type heat conduction equation by optimization method. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 362, 210–223 (2010)

Deng, Z.C., Yu, J.N., Yang, L.: Optimization method for an evolutional type inverse heat conduction problem. J. Phys. A, Math. Theor. 41, 035201 (2008)

Derman, E., Kani, I., Chriss, N.: Implied trinomial trees of the volatility smile. J. Deriv. 4, 7–22 (1996)

Dupire, B.: Pricing with a smile. Risk 1, 18–20 (1994)

Gatteral, J., Jauqier, A.: Arbitrage-free SVI volatility surfaces. Quant. Finance 1, 59–71 (2014)

Isakov, V.: Inverse parabolic problems with the final overdetermination. Commun. Pure Appl. Math. 2, 185–209 (1991)

Isakov, V.: Inverse Problems for Partial Differential Equations. Springer, New York (1998)

Jiang, L.S., Bian, B.J.: The regularized implied local volatility equations – a new model to recover the volatility of underlying asset from observed market option price. Discrete Contin. Dyn. Syst., Ser. B 6, 2017–2046 (2012)

Jiang, L.S., Chen, Q.H., Wang, L.J., Zhang, J.E.: A new well-posed algorism to recover implied local volatility. Quant. Finance 6, 451–457 (2003)

Jiang, L.S., Tao, Y.S.: Identifying the volatility of underlying assets from option prices. Inverse Probl. 1, 137–155 (2001)

Ladyzenskaya, O., Solonnikov, V., Ural’ceva, N.: Linear and Quasilinear Equations of Parabolic Type. Am. Math. Soc., Providence (1968)

Mitsuhiro, M., Ota, Y.: Recovery of foreign interest rates from exchange binary options. Comput. Technol. Appl. 2, 76–88 (2015)

Mohebbi, A., Dehghan, M.: High-order scheme for determination of a control parameter in an inverse problem from the over-specified data. Comput. Phys. Commun. 181, 1947–1954 (2010)

Prilepko, A.I., Orlovsky, D.G., Vasin, I.A.: Methods for Solving Inverse Problems in Mathematical Physics. Dekker, New York (2000)

Rubinstein, M.: Implied binomial trees. Finance 3, 771–818 (1994)

Rundell, W.: The determination of a parabolic equation from initial and final data. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 4, 637–642 (1987)

Shamsi, M., Dehghan, M.: Determination of a control function in three-dimensional parabolic equations by Legendre pseudospectral method. Numer. Methods Partial Differ. Equ. 28, 74–93 (2010)

Tadi, M., Klibanov, M.V., Cai, W.: An inversion method for parabolic equations based on quasireversibility. Comput. Math. Appl. 8–9, 927–941 (2002)

Wilmott, P.: Derivatives – the Theory and Practice of Financial Engineering. Wiley, London (1998)

Yang, L., Yu, J.N., Deng, Z.C.: An inverse problem of identifying the coefficient of parabolic equation. Appl. Math. Model. 10, 1984–1995 (2008)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the anonymous referees for their valuable comments and helpful suggestions to improve the earlier version of the paper.

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 11461039, 61663018, 11961042), Foundation of A Hundred Youth Talents Training Program of Lanzhou Jiaotong University and NSF of Gansu Province of China (No. 18JR3RA122).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZCD established a mathematical model and analyzed the well-posedness of the model. XYZ designed the program and provided numerical examples. LY performed literature collection and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Deng, Z.C., Zhao, X.Y. & Yang, L. An inverse problem of reconstructing option drift rate from market observation data. Bound Value Probl 2021, 37 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13661-021-01506-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13661-021-01506-9