Abstract

Background

A lack of safety data on postpartum medication use presents a potential barrier to breastfeeding and may result in infant exposure to medications in breastmilk. The type and extent of medication use by lactating women requires investigation.

Methods

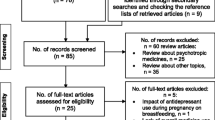

Data were collected from the CHILD Cohort Study which enrolled pregnant women across Canada between 2008 and 2012. Participants completed questionnaires regarding medications and non-prescription medications used and breastfeeding status at 3, 6 and 12 months postpartum. Medications, along with self-reported reasons for medication use, were categorized by ontologies [hierarchical controlled vocabulary] as part of a large-scale curation effort to enable more robust investigations of reasons for medication use.

Results

A total of 3542 mother-infant dyads were recruited to the CHILD study. Breastfeeding rates were 87.4%, 75.3%, 45.5% at 3, 6 and 12 months respectively. About 40% of women who were breastfeeding at 3 months used at least one prescription medication during the first three months postpartum; this proportion decreased over time to 29.5% % at 6 months and 32.8% at 12 months. The most commonly used prescription medication by breastfeeding women was domperidone at 3 months (9.0%, n = 229/2540) and 6 months (5.6%, n = 109/1948), and norethisterone at 12 months (4.1%, n = 48/1180). The vast majority of domperidone use by breastfeeding women (97.3%) was for lactation purposes which is off-label (signifying unapproved use of an approved medication). Non-prescription medications were more often used among breastfeeding than non-breastfeeding women (67.6% versus 48.9% at 3 months, p < 0.0001), The most commonly used non-prescription medications were multivitamins and Vitamin D at 3, 6 and 12 months postpartum.

Conclusions

In Canada, medication use is common postpartum; 40% of breastfeeding women use prescription medications in the first 3 months postpartum. A diverse range of medications were used, with many women taking more than one prescription and non-prescription medicines. The most commonly used prescription medication by breastfeeding women were domperidone for off-label lactation support, signalling a need for more data on the efficacy of domperidone for this indication. This data should inform research priorities and communication strategies developed to optimize care during lactation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Breastfeeding has various important maternal and child health benefits which includes facilitating maternal-infant bonding and delivering necessary nutrients and antibodies for the infant’s develo** immune system [1]. Exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months and then continuing breastfeeding up to two years or more after introducing solid foods is recommended by many organizations including World Health Organization (WHO) and Health Canada [1, 2]. In Canada, breastfeeding initiation rates in hospital are high at 89% (reported in 2011/12), however, continued rates of breastfeeding post-discharge are much lower, as only 26% of mothers reported breastfeeding exclusively for six months or more [3]. Support and encouragement for mothers who wish to breastfeed is an important public health initiative which includes a thorough investigation of barriers to sustained breastfeeding.

Medication use, without adequate safety data, is a potential barrier to breastfeeding due to risks of infant exposure through breastmilk [4]. Mothers may have acute or chronic health conditions that require the use of medications in the postpartum period. Prescription medications, non-prescription medications (NPM) such as ibuprofen or allergy medicines, and supplements may be necessary for their clinical care and well-being. Medication transfer and safety during lactation are rarely studied during drug development [4, 5]. Mothers requiring medications and their health care providers may be ill-informed about the risks of nursing while taking medications and supplements [4]. This can result in an absolute risk avoidance approach to either stop breastfeeding or discontinue taking medications to avoid possible (unknown) adverse effects on their child [4]. It is critical for health professionals to assess the risk and benefits for both mother and child, including the risks of not breastfeeding, when advising on postpartum medication decisions for women who wish to breastfeed. Most medications are considered relatively safe for infants that are breastfed [5]. There are a few medications that might be relatively contraindicated during breastfeeding which include lithium, oral retinoids, amiodarone, gold salts and anticancer medications [6]. For most medications further knowledge is required to understand the effects during breastfeeding. It is recommended that health care providers review medications on a case-by-case basis for suitability and advice regarding risk management. A study by Hale et al., reported that common medications used in the postpartum period include analgesics, antihypertensives, sedatives, antidepressants, antipsychotics, antiepileptics, antibiotics, and steroids; however, breastfeeding patterns and rates were not reported [5].

The primary aim of the present study is to identify the most commonly used prescription medications and NPM among breastfeeding mothers in a Canadian prospective cohort study. Our secondary aims were to characterize patterns of medication use based on therapeutic categories among breastfeeding women and non-breastfeeding women, describe indications of prescription medication use, and explore differences in medication use by study site.

Methods

Study population

Data were collected from the Canadian CHILD Cohort Study [7]. In the CHILD study, pregnant women in their second and third trimester were recruited between 2008 and 2012 at 4 sites across Canada - Vancouver, Edmonton, Manitoba (Winnipeg, Morden, Winkler) and Toronto [7]. Women were eligible to participate if they gave birth to a singleton infant at > 35 weeks gestational age. Infants who were born premature (≤ 35 weeks), born with respiratory distress syndrome, complications or fetal abnormalities or born through an in vitro fertilization were excluded [7]. A total of 3542 mother-infant dyads were originally recruited to the CHILD study [7]. The CHILD study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Boards at McMaster University and at the Universities of Alberta, British Columbia, and Manitoba, and the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto [8]. Our subsequent analysis was approved by the Health Research Ethics Bord of the University of Manitoba.

Medication classification and breastfeeding status

Each participant was asked to complete a questionnaire at 3, 6 and 12 months postpartum identifying any prescription medications or NPMs including vitamins and supplements used during the first 3 months postpartum, 3 to 6 months postpartum and 6 to 12 months postpartum, specifying the medication/product type. Participants were also able to self-report their reason for using a specific prescription medication, but this was not required. There was no option to report indication for NPM. The reported medications were classified as prescription medications or NPM, based on the individual drug monographs as per Drug Product Database online query from Health Canada which classifies prescription medications or NPMs according to Food and Drug Regulations, and the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act [9].. Prescription medications and NPM were then further classified based on their therapeutic class based on the drug database, Lexicomp [10]. Information about breastfeeding status was obtained at 3, 6 and 12 months postpartum from self-reported questionnaires. Breastfeeding was defined using WHO definition as “breast milk, including milk that was expressed” and therefore includes pumped milk [11]. Mothers were classified into the breastfeeding versus the non-breastfeeding group at each time point postpartum.

Large scale data curation with ontologies, and statistical analyses

Medication brand names were corrected for spelling errors and the generic names of the medications were then identified. When the brand name was not specific, a broad ontology term was provided instead of the generic name. The most common prescription medications and NPM used by breastfeeding women (BFW) for each time point were described by study site to identify signals of regional variability. To analyze reasons for medication use, free text entries were corrected for spelling errors and then standardized using ontology terms from Human Disease Ontology, Human Phenotype Ontology, National Cancer Information Thesaurus, Adverse Event Ontology, and Symptom Ontology. There was an initial automated analysis through the Disease Ontology (DOID), Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO), Symptom Ontology (SYMP), Ontology of Adverse Events (OAE) and the National Cancer Institute Thesaurus (NCIT) using a Ontoma python wrapper to match the free text to the above defined ontology [12,13,14,1). This information is important to signal potential therapeutic areas where patients may be less likely to initiate or sustain breastfeeding as an example non-breastfeeding women used significantly more psychotropic medications than non-breastfeeding medications.

Our results were comparable to other studies that found that vitamins were more frequently used by BFW as was recommended [17, 21]. Most healthcare providers recommend continuation of prenatal vitamins during lactation which may also explain these findings. Differences were identified in rates of multivitamins across the study sites with highest use in Vancouver at 3 and 6 months postpartum. This could be explained by previous coverage available for some vulnerable populations through programs such as BC Employment and Assistance in Vancouver until seven months postpartum while no coverage is found that specifically tailors to lactating women in Manitoba, Edmonton or Toronto [22,23,24]. These results might reflect the effectiveness of a coverage program for prenatal findings in the postnatal period. Differences in medication were also observed between sites, for example domperidone was used the most in Vancouver at 3 months and norethisterone was used the most in Edmonton at 12 months. It was unclear why this pattern existed.

Our analysis showed that BFW used psychotropic medications at a rate lower (4.3% at 3 months postpartum) than the general population while NBFW used these agents at a rate closer to the general population (11.2% at 3 months postpartum). According to the 2002 Canadian census, the rate of psychotropic medication use in Canadian women age 15 years and older was 9.5% [25]. This pattern is a complex issue which could be explained by recent literature showing woman taking psychotropic agents are less likely to initiate breastfeeding or have higher rate of breastfeeding cessation [26]. Other studies also found that psychotropic medications were more commonly used by NBFW [17]. A previous study reported that about 16.9% women who received psychotropic medication discontinued breastfeeding although in most cases it was not due to psychiatrists recommendation or adverse events due to medications [27].

In addition to this, at 3 months specifically, significantly more NBFW used opioid analgesics than BFW. Opioid analgesics transfer into maternal milk; medications such as fentanyl and propoxyphene are considered safe during lactation while codeine, tramadol, morphine, hydromorphone, methadone and oxycodone are considered moderately safe during breastfeeding [28]. The most commonly used oral-contraceptives for all women postpartum was norethisterone (a progestin-only contraceptive) which is predictable since it has been shown that the estrogen component of combined oral contraceptives may cause a decline in breast milk volume [29]. A previous study showed women taking progestogen-only contraception were less likely to stop breastfeeding before 6 months postpartum compared to combined contraception with estrogen [29]. This could explain the higher use of norethisterone in BFW than NBFW in our analysis. In this cohort, hormonal contraceptives were reported more commonly in women who were not breastfeeding which has been reported in other studies [17]. Levothyroxine was among the most common prescription medications used by both BFW and NBFW. The indication for levothyroxine is thyroid dysfunction such as postpartum thyroiditis which has a prevalence of approximately 8.1% according to studies done in the US [30]. Mothers in this cohort appear to be using the medication in accordance with this indication as the majority of mothers self-reported using levothyroxine to combat hypothyroidism.

The most commonly used anti-infective at 3 months postpartum was cephalexin, with no significant difference in cephalexin use between BFW and NBFW in the first 3 months postpartum which could be indicated for treating mastitis or breast abscess associated with breastfeeding. Mothers self-reported using antibiotics for mastitis, unspecific infections, and other breast abnormalities related to lactation which likely contributed to the increased number of BFW taking antibiotics. Approximately 75–95% of cases of mastitis occur before the infant is 3 months of age and cephalexin is a common treatment option [31]. On the other hand, the overall similar rates of cephalexin use between breastfeeding and non-breastfeeding women at 3 months could also indicate that non-breastfeeding women taking antibiotics could have stopped breastfeeding due to mastitis. There is evidence revealing that women with mastitis have poorer breastfeeding outcomes and higher rates of abrupt breastfeeding cessation although whether this relates to mastitis itself of use of antibiotics is unclear [32].At 6 and 12 months postpartum, vitamin/minerals and non-opioid analgesics were the most commonly used categories by BFW. This is similar to findings in a Brazilian study which evaluated medication use during the first 12 months and found that the most commonly used class of medications were analgesics/antipyretics, iron preparations and NSAIDs [4, 17]. Our study supports this as the most common non-prescription medications were a variety of vitamins/minerals, analgesics such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen at 3, 6 and 12 months postpartum. A study in Jordan done in 2015, also similarly found that the most commonly used medications were analgesics followed by antibiotics [33]. Another study by Hale et al., reported that common medications used in the postpartum period include analgesics, antihypertensives, sedatives, antidepressants, antipsychotics, antiepileptics, antibiotics, and steroids [5]. Our analysis partially aligns with anti-infectives being the most common therapeutic category used at 3 months (after supplements/herbal products and vitamins/minerals) and analgesics being the most common at 6 and 12 months (after vitamins/minerals) among BFW.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of our study is the inclusion of pattern of use of NPM which included over-the-counter medications and other medications allowing us to analyze the use of products that are not available as part of provincial administrative health data (e.g. DPIN prescribing records). One of the main limitations is the accuracy of self-reported medication use and the timing of medication use and breastfeeding reporting. As we were not able to compare the exact breastfeeding stop date and medication exposure date, misclassification of non-breastfeeding women is possible. For example, it is uncertain whether some women might have stopped breastfeeding to take certain medications or were taking certain medications that resulted in breastfeeding difficulties and earlier breastfeeding discontinuation. Further studies are required to explore potential sources of confounding. Another limitation is that there was overlap of prescription medications and non-prescription medications under most therapeutic categories. As an example, under the category ‘anti-allergy’ medications, there might be prescription and non-prescription medications. Under-reporting of medication use by mothers may occur for various reasons, including recall bias. A study examined validity of questionnaires about medication use during pregnancy by comparing with pharmacy records, and found the questionnaire had 76% sensitivity when a question was asked in an indication-oriented fashion, however some medications were mentioned that were missed by pharmacy records [34]. In the CHILD questionnaire, women were given examples of common indications for medications in order to aid in the recall of the mothers about their medication use. Another limitation is the presence of selection bias and response bias where the mother-infant dyads might not be representative of the whole Canadian population. Women who had a higher education level who had at least some college or university experience (93.6%) were over-represented in this analysis compared to the general population, as were women who initiated breastfeeding in hospital (96.5%) which was higher than the Canadian average (89%), and therefore our results may not be generalizable at the population level [35]. Another limitation is that indications for medication use questionnaires utilized free text and therefore many mothers did not respond which does not provide an accurate representation of all the indications for medication use.

Although, there have been more recent studies on postpartum medication use which were mentioned above and aligned with our results, it is important to continue to evaluate medication use in women postpartum to assess continued relevancy of our analysis in the Canadian population. To our knowledge this is the largest, curated and ontologized dataset of self-reported “reasons for medication use” for BFW. While limited, since response was optional, this does provide some insight into the perceptions and rationale behind medication use, which would not be available otherwise. In particular, it provided important confirmation of off-label domperidone use in the breastfeeding and non-breastfeeding population. This study supports further research into the prevalence and effectiveness of domperidone prescribed for insufficient lactation.

Epidemiological data on medication use patterns and reasons for use during lactation is key to informing public health policies and clinical care guidelines. This analysis collectively provides an important description of medications and supplements being used during breastfeeding, along with ontologized reasons for use, which lays the groundwork for future studies to enable healthcare providers and breastfeeding mothers to make evidence-informed decisions regarding the risk of discontinuation of a medication, safety of alternative medications as well as risk of exposures to medications/supplements during lactation on maternal-child health.

Data availability

Data available within the article or its additional files.

References

The optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding. Report of an expert consultation. World Health Organization; 2001.

Duration. of Exclusive Breastfeeding in Canada. Health Canada. 2010.

Gionet L. Breastfeeding trends in Canada. Health a Glance. 2013.

Saha MR, Ryan K, Amir LH. Postpartum women’s use of medicines and breastfeeding practices: a systematic review. Int Breastfeed J. 2015;10:28.

Hale TW. Hale’s medications & mothers’ milk 2019: a Manual of Lactational Pharmacology. 18th ed. Springer Publishing Company; 2019.

Hotham N, Hotham E. Drugs in breastfeeding. Australian Prescriber. 2015;38(5):156–9.

Subbarao P, Anand SS, Becker AB, Befus AD, Brauer M, Brook JR, et al. The Canadian healthy infant Longitudinal Development (CHILD) study: examining developmental origins of allergy and asthma. Thorax. 2015;70(10):998–1000.

Azad MB, Robertson B, Atakora F, Becker AB, Subbarao P, Moraes TJ, et al. Human milk oligosaccharide concentrations are associated with multiple fixed and modifiable maternal characteristics, environmental factors, and feeding practices. J Nutr. 2018;148(11):1733–42.

Drug Product Database online query Internet. Health Canada. 2019. Available from: https://health-products.canada.ca/dpd-bdpp/index-eng.

Lexi-Drugs. Lexicomp Internet, Riverwoods IL. Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc; Available from: http://online.lexi.com.

Noel-Weiss J, Boersma S, Kujawa-Myles S. Questioning current definitions for breastfeeding research. Int Breastfeed J. 2012;7:9.

Schriml LM, Munro JB, Schor M, Olley D, McCracken C, Felix V, et al. The Human Disease Ontology 2022 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50(D1):D1255–61.

Robinson PN, Köhler S, Bauer S, Seelow D, Horn D, Mundlos S. The human phenotype ontology: a Tool for Annotating and analyzing Human Hereditary Disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83(5):610–5.

NCI Thesaurus. National Cancer Institute. Available from: https://ncithesaurus.nci.nih.gov/ncitbrowser/.

He Y, Sarntivijai S, Lin Y, **ang Z, Guo A, Zhang S, et al. OAE: the Ontology of adverse events. J Biomedical Semant. 2014;5:29.

Ontoma Internet. Open Targets Revision. 2021. Available from: https://ontoma.readthedocs.io/en/stable/development.html.

Chaves RG, Lamounier JA, Cesar CC. Self-medication in nursing mothers and its influence on the duration of breastfeeding. J Pediatr. 2009;85(2):129–34.

Taylor A, Logan G, Twells L, Newhook LA. Human milk expression after domperidone treatment in postpartum women: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Hum Lactation. 2018;35(3):501–9.

Majdinasab E, Haque S, Stark A, Krutsch K, Hale T. Psychiatric manifestations of withdrawal following domperidone used as a galactagogue. Breastfeed Med. 2022;17(12):1018–24.

Summary Safety Review - Domperidone - Health Canada. Government of Canada. 2021.

Jun S, Gahche JJ, Potischman N, Dwyer JT, Guenther PM, Sauder KA, et al. Dietary Supplement Use and Its Micronutrient Contribution During Pregnancy and Lactation in the United States. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2020;135(3):623–33.

Natal Supplement. British Columbia. Available from: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/governments/policies-for-government/bcea-policy-and-procedure-manual/health-supplements-and-programs/natal-supplement.

The prescription drugs cost assistance act. British Columbia 2020. Available from: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/family-social-supports/income-assistance.

Interactive Drug Benefit List. 2020. Available from: https://idbl.ab.bluecross.ca/idbl/drugDetails?_cid=3835f505-be9a-4e46-a8d0-7f6627b991d2&id=0000087265&intchg_grp_nbr=1&detailId=3114828.

Beck CA, Williams JVA, Jian LW, Kassam A, El-Guebaly N, Currie SR, et al. Psychotropic medication use in Canada. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;50(10):605–13.

Grzeskowiak LE, Saha MR, Nordeng H, Ystrom E, Amir LH. Perinatal antidepressant use and breastfeeding outcomes: Findings from the Norwegian Mother, Father and Child Cohort Study. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2022;101(3):344–54.

Uguz F, Kirkas A, Aksoy ZK, Yunden S. Use of psychotropic medication during lactation in postpartum psychiatric patients: results from an 8-year clinical sample. Breastfeeding Medicine. 2020;18(8):535–537.

Kraychete DC, Siqueira JTT de, Zakka TRM, Garcia JBS. Recommendations for the use of opioids in Brazil: Part III. Use in special situations (postoperative pain, musculoskeletal pain, neuropathic pain, gestation and lactation). Revista Dor. 2014;15(2):126–32.

Lutz BH, Bassani DG, Miranda VIA, Silveira MPT, Mengue SS, Dal Pizzol T da S, et al. Use of medications by breastfeeding women in the 2015 pelotas (Brazil) birth cohort study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(3):989.

Stagnaro-Green A, Abalovich M, Alexander E, Azizi F, Mestman J, Negro R, et al. Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the diagnosis and management of thyroid disease during pregnancy and postpartum. Thyroid. 2011;21(10):1081–125.

Boakes E, Woods A, Johnson N, Kadoglou N. Breast Infection: A Review of Diagnosis and Management Practices. European Journal of Breast Healh. 2018;14(3):136–43.

Grzeskowiak LE, Saha MR, Ingman W V., Nordeng H, Ystrom E, Amir LH. Incidence, antibiotic treatment and outcomes of lactational mastitis: Findings from The Norwegian Mother, Father and Child Cohort Study (MoBa). Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 2022;36(2):254–63.

Al-Sawalha NA, Tahaineh L, Sawalha A, Almomani BA. Medication use in breastfeeding women: a national study. Breastfeeding Medicine. 2016;11:386–91.

De Jong Van Den Berg LTW, Feenstra N, Sorensen HT, Cornel MC. Improvement of drug exposure data in a registration of congenital anomalies. Pilot-study: Pharmacist and mother as sources for drug exposure data during pregnancy. Teratology. 1999;60(1):33–6.

Gionet L. Breastfeeding trends in Canada. Health at a Glance. Statistics Canada Catalogue. 2013. 82(624).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the families who took part in this study, and the whole CHILD Cohort Study team, which includes interviewers, nurses, physicians, computer and laboratory technicians, clerical workers, research scientists, volunteers, managers, and receptionists.

Funding

The Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Allergy, Genes and Environment Network of Centres of Excellence (AllerGen NCE) provided core support for the CHILD Cohort Study. This research was specifically funded by the Rady Innovation Fund at the University of Manitoba, with supporting funding from the Genome Canada CHILD LSARP project. EG is supported by an NSERC CREATE in Bioinformatics and UY is supported by a CIHR Canada Graduate Scholarship. MBA is supported by a Tier 2 Canada Research Chair and is a Fellow of the CIFAR Humans and the Microbiome Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.S. and U.Y. wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The CHILD study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Boards at McMaster University and at the Universities of Alberta, British Columbia, and Manitoba, and the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto.(8) Our subsequent analysis was approved by the Health Research Ethics Bord of the University of Manitoba.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Soliman, Y., Yakandawala, U., Leong, C. et al. The use of prescription medications and non-prescription medications during lactation in a prospective Canadian cohort study. Int Breastfeed J 19, 23 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-024-00628-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-024-00628-x