Abstract

Background

Black-boned sheep is a precious genetic resource with black quality traits cultivated by the Pumi people in Tongdian Town, Lan** County, Nujiang Lisu Autonomous Prefecture, Northwest Yunnan, China. It has been included in the “National Breed List of Livestock and Poultry Genetic Resources.” The local communities have a deep understanding of black-boned sheep. The traditional knowledge of black-boned sheep is essential to their conservation and sustainable development. In spite of this, there was no information on traditional knowledge associated with black-boned sheep so far. The aim of this study wasaimed to document traditional knowledge and culture, to elucidate information about forage plants, and to investigate the conservation strategy of black-boned sheep.

Method

Four field surveys were conducted from July 2019 to May 2021. A total of seven villages and the Pumi Culture Museum in Lan** County are being investigated. A semi-structured interview method was used to interview 67 key informants. During the investigation, we also participated in the grazing activities of black-boned sheep, observed the appearance characteristics and the herd structure of the black-boned sheep, and demonstrated traditional knowledge regarding black-boned sheep, including grazing methods, forage plants, and related customs and habits.

Results

We assumed that a majority of people in the current study sites were able to could distinguish black-boned sheep from their relatives by their black bones, blue-green gums, and blue-purple anus. The local people manage their black-boned sheep based on the number of sheep by sex, age, and role in a flock in the different breeding environments. Different grazing strategies have been adopted in different seasons. Through ethnobotanical investigations, 91 species of forage plants in 30 families were identified, including herbaceous, shrubs, lianas, and trees. Among all the plant species consumed by the black-boned sheep, Rosaceae species make up the greatest number, with 16, followed by Asteraceae, with 9, and 8 species of Fabaceae and Poaceae. Considering the abundance of forage plants and the preference for black-boned sheep, Prinsepia utilis and the plants of Rubus, Berberis, and Yushania occupy dominant positions. Plants used for foraging are divided into two categories: wild and cultivated. Due to the lack of forage plants in fall and winter, the local people mainly cultivate crops to feed their black-boned sheep. In addition, the black-boned sheep is an influential cultural species in the local community and plays a prominent role in the cultural identity of the Pumi people.

Conclusion

Sheep play an essential role in the inheritance of the spiritual culture and material culture of the Pumi ethnic group. The formation of the black-boned sheep is inseparable from the worship of sheep by the Pumi people. With a long-term grazing process, the locals have developed a variety of traditional knowledge related to black-boned sheep. This is the experience that locals have accumulated when managing forests and grasslands. Therefore, both the government and individuals should learn from the local people when it comes to protecting black-boned sheep. No one knows black-boned sheep better than them. The foremost evidence of this is the rich traditional knowledge of breeding black-boned sheep presented by key informants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since prehistoric times, domesticated livestock, and poultry have played an essential role in human societies. The survival and development of small-scale farmers in many parts of the world are closely related to domestic animals [1,2,3,4,5]. On the one hand, domestic animals, especially livestock ruminants, provide labor and fertilizer for small-scale farmers, hel** them integrate and efficiently use limited land resources [6,7,8]. In addition to providing nutrition, domestic animals also generate income for small-scale farmers in the forms of meat, eggs, milk, etc. [9, 10]. Over the past decade, animal husbandry has shown much closer relationships with several other fields. These include food security, biodiversity conservation, environmental protection, and rural poverty alleviation [11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. Earlier studies demonstrated that livestock and poultry genetic resources in minority areas could serve as a major strategic resource for a nation and contribute significantly to global biodiversity [18,19,20,21]. As a consequence, many countries are placing a greater emphasis on develo** animal husbandry. In one aspect, the government will protect rare domestic animal resources by issuing relevant policies and financial incentives. Contractually, vaccination campaigns for domestic animals and the professional knowledge training for breeders must be strictly adhered to [22,23,24,25,26]. However, research shows that the development of animal husbandry fundamentally relies on the original breeding environment of domestic animals. The most appropriate breeding methods could only be determined by combining the traditional knowledge of indigenous people with scientific knowledge. In sum, we can summarize the forage plant species that indigenous people use in raising a certain type of livestock. We can also build a database of relevant forage plants, and assess the selection preference of this domestic animal for forage. Then, the most suitable feed can be selected when develo** the related breeding industry [2, 7, 8]. A number of studies related to this have been conducted around the world [6,7,8,9, 27,28,29].

China has a huge land area, diverse topography and landforms, an abundance of natural resources, and a long history of the domestication of livestock and poultry. There is a rich cattle culture in China, which overlaps deeply related with traditional customs, farming life, and cognitive psychology, where cattle cover Bos and Bulalus. This has resulted in a rich diversity of livestock and poultry resources throughout the country [30, 31]. China is one of the countries with the most extensive livestock and poultry genetic resources in the world. Due to its wide geographical distribution and uneven protection of livestock and poultry resources, China is also one of the countries where livestock and poultry genetic resources are seriously threatened [32, 33]. In general, China’s local livestock and poultry resources are generally showing a downward trend. Many local breeds are on the verge of extinction, and some have even become extinct, making the situation of local livestock and poultry breed resources not optimistic [34, 35]. Hence, they need to be protected with proper strategies.

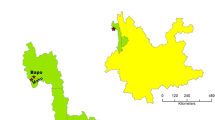

Black-boned sheep is a unique genetic resource of livestock that has been raised and domesticated by the Pumi people in Tongdian, a township in Lan** County, Yunnan Province, for a long time. It is considered to be the second animal with heritable characteristics of melanin in the world besides the black-boned chicken, and it is the only mammal that has been found to contain a large amount of melanin in the body so far [36,37,38,42]. Since the black-boned sheep was first discovered in 2001, it has attracted much attention. In 2006, the country officially named the sheep as “Lan** black-boned sheep” according to its origin and characteristics, which was identified and approved by the expert group of the National Animal and Poultry Genetic Resources Appraisal Committee in October 2009. In the same year, it was listed in the “National List of Animal and Poultry Genetic Resources,” “China Rare Animal Breeds List” and “World Rare Animal Species List” [ Tongdian Township is located at the southernmost end of the World Natural Heritage Protection Area “Three Parallel Rivers,” with a complete ecosystem and rich biodiversity. The Tongdian covers a total area of 521.33 km2, the highest elevation is 3688 m, the lowest elevation is 2237 m, the annual average temperature is 10.7 °C, the annual average accumulated temperature is 2840 °C, and the annual average rainfall is about 1024.1 mm. Tongdian is home to 9 ethnic groups, including Bai, Pumi, Yi, and Lisu. Due to limited communication with the outside world, local ethnic groups still retain the habit of planting old varieties of crops and raising old varieties of poultry and livestock [48,52,53,56,57]. This lack of written records means that local traditional knowledge is particularly prone to loss and extinction. Consequently, there is an urgent need to record indigenous knowledge related to this ethnic group. Black-boned sheep have been raised by Pumi people for a long time and they rarely exchange sheep with the outside world. They commonly grow at an altitude of about 1900–2800 m, and the breeding range is within 30 km of Tongdian. With economic development, sheep breeds from outside have been introduced, which not only threatens the integrity of the native black-boned sheep but also reduces the number of farmers who breed black-boned sheep. To protect black-boned sheep, the local government encourages local companies to set up breeding plants to breed black-boned sheep. However, what kind of feed is suitable for black-boned sheep and what breeding methods can ensure the high quality of black-boned sheep require further investigation. Our ethnobotanical survey was mainly carried out in Tongdian Town, the original habitat of black-boned sheep. We conducted three surveys in Desheng, Longtan, Fenghua, **zhu, Huangsong, Fudeng, Nugong villages in Tongdian Town, and Pumi Culture Museum in Lan** County from 2019 to 2021 (Fig. 1). Before the investigations, all reporters were informed of the purpose of the investigations and obtained their consent. Methods to collect data include free listing, semi-structured interviews, and participatory observation. A total of 67 key informants were screened using the snowball sampling method, including 48 males and 19 females, with an average age of 57 years old [58, 59]. Semi-structured interviews are conducted in response to the questions in Table 1. A participatory observation was conducted with the locals during the grazing activities. During this process, forage plant specimens are collected and the forage feeding of the black-boned sheep in their wild habitat is observed (Fig. 2). Nomenclature of all vascular plants was followed Flora of China, and World Flora Online (www.worldfloraonline.org) as well. Professor Chunlin Long and Dr. Bo Liu identified the plant species. The voucher specimens were deposited in the Herbarium of the College of Life and Environmental Sciences, Minzu University of China, in Bei**g [60]. All data information is based on the first-hand information provided by 67 key informants, including the used parts of forage plants, the number of forage reserves in the wild, the preference of black-boned sheep, etc. (also see items 3 and 5 in Table 1). Regarding the abundance of forage plants in the field, we evaluated the frequency of encountering the plants during the investigation. In this area, if we encountered a plant species only 1–2 times, this indicates a low abundance 3–4 times for medium abundance, and more than 4 times (5 and over) for high abundance. The preference for forage was evaluated by the number of times recommended by key informants. The more frequently this is mentioned, the more black-boned sheep will flock here to graze. From a morphological point of view, the black-boned sheep is similar to Tibetan sheep in that it has a wide chest, straight back, large abdomen but not droo**, relatively short body, strong limbs, short tail, and conical shape. The head and limbs are poorly covered with wool and the coat is thick. The blackness of the black-boned sheep has nothing to do with the color of the coat. The older an individual is, the deeper the blackness will be. The difference between black-boned sheep and other sheep is that the eye conjunctiva is brown, the skin of the elbow joints of the forelegs and hind limbs is purple, the skin of the hair roots and underarms of the white wool black-boned sheep is purple, the mouth and tongue are bright black, the gums are blue-green, and the anus is blue-purple. These characteristics of black-boned sheep allow local people to distinguish them from other sheep. According to key informants, if the flock of black-boned sheep can be organized reasonably during grazing, it will save labor and facilitate the management of the flock. The local communities must determine the number, sex, and age composition of the black-boned sheep based on the breeding area and grazing environment. If the place has a large pasture or pasturing area, the proper number of black-boned sheep is 400–450, of which 200–250 ewes are used to breed lambs and breed as mutton sheep, 150–200 rams are castrated, as a meat sheep fattening, and the remaining 50–100 rams are used to breed ewes. However, if there is no large area of pasture in the area, the number of sheep should not be too big, usually around 100. Black-boned sheep are accustomed to moving on hillsides and dense forests, looking for food everywhere (Fig. 2). A large amount of activity makes the black-boned sheep stronger and stronger. Therefore, most of the time, the black-boned sheep do not need to be looked after. In the winter, when the mountains are covered in snow and rain, they need warm houses. In Pumi communities, sheepfolds are generally rebuilt from dilapidated old houses, or built with materials available everywhere, such as stones, branches, and bamboo, at low cost. Shepherds are usually 1 m high to prevent them from esca** beyond the pen. According to demand, dry crop straw and hay can be laid in the pen in winter to help the black-boned sheep keep warm. The Pumi people do not have their own specific pastures. The mountain forests, grasslands, and wasteland around the villages can become natural pastures for black-boned sheep, and farmers in the same village share these resources. The Pumi people distinguish their sheep when grazing by putting bells on their necks so they do not get confused with others' sheep. They also mark head sheep’s bodies. As long as the head sheep is mastered, the other sheep will not run around. According to key informants, the flock also recognizes the voice of its owner. When grazing, the local people will consciously change their positions constantly to prevent the sheep from over-grazing on the vegetation in an area and causing grassland degradation. Moreover, the high mobility of the black-boned sheep further causes it to constantly change its feeding location. The local government will also fence off the pastures in a certain area and close them for a few seasons for the purpose of restoring vegetation. For the Pumi people, the black-boned sheep is a treasure. The wool is used for spinning, weaving, and making their traditional clothing. The sheepskin can be incorporated into a felt hat for the Pumi people to keep warm in winter. Its milk can also be made into a variety of dairy snacks. But the most important thing for the Pumi people is the meat of the black-boned sheep, which is not only an important source of income for them, but serves as a significant source of protein for maintaining physical strength. In the Pumi community, it is very common to consume mutton. In addition to eating fresh, black-boned mutton can also be preserved by processing. Most of the black-bone sheep they raise are sold to buyers from various places, and then appear on the markets in the form of mutton. Importantly, sheep manure produced by black-boned sheep in captivity in winter is a highly effective natural fertilizer. As part of their gardening practices, the Pumi people usually spread it evenly on the vegetable fields in front of and behind their houses. Various problems need to be addressed during different grazing seasons. These issues are also the criteria for testing whether a shepherd is qualified. It is not advisable to graze too early in spring. On the one hand, it is cold in the morning, and the new shoots of the forage grass have high moisture content and carry dew. If the sheep eat too much, it will cause diarrhea. On the other hand, sheep graze on hay throughout the winter. They will become greedy when they see fresh green grass. Under the leadership of the leader, the sheep will run around looking for grass to eat. This will not only cause the sheep to feed on grass without growing meat but also cause poisoning due to accidental eating of poisonous weeds. In addition, eating too much grass will also lead to indigestion and flatulence. In this regard, there is a famous proverb in the local community: “stop the leader, the sheep will be fat and strong; let the leader go, the sheep will not grow fat.” To avoid these situations, the locals will feed some hay to the sheep before they start grazing, and then let the sheep move freely. The hay is usually the dried aerial parts of crops like Avena sativa L., Pisum sativum L., etc., which are harvested and threshed in the summer or autumn, and stacked in wooden houses (Fig. 3). Summer is hot and rainy, so grazing activities should follow the guidelines of starting out early and returning late to prevent heatstroke in the flock. At noon, let the flock rest in a ventilated and shaded place to prevent the flock from getting together, and provide the sheep with more water. Autumn is the season for sheep to gain weight so they can survive the cold winter. At this time, the pasture is abundant, and there are also many mature wild fruits to help the sheep improve their diet and supplement nutrition. Moreover, autumn is also the peak season for sheep to ovulate and mate. Therefore, the shepherd should focus on letting the sheep eat enough and well, breeding for sale, safe overwintering, and offspring reproduction. As the winter turns cold, the plants begin to wither and are accompanied by rain, snow, and frost. When grazing, it is important to keep lambs warm, prevent them from getting cold, and to keep them healthy. The sheep usually graze near a village or farmland, where leaves and hay are available for them to eat. When the weather is fine, the sheep can be properly basked in the sun, but do not allow pregnant ewes to exercise vigorously. In addition, the sheep shed must be properly maintained before the snow arrives. In addition, it is essential to feed the sheep regularly with crushed hay feed mixed with salt and lard. According to locals, this can help digestion, increase appetite, and supplement nutrition. When grazing, it is also necessary to ensure that the sheep are allowed to drink water at least once a day, preferably from a mountain spring. The shepherd has rich knowledge of plant species or plant parts preferred to eat by black-boned sheep. In our research, we documented that black-boned sheep consumed forage plants. A total of 91 forage plants were recorded (Table 2), including 57 species of herbaceous plants, 20 species of shrubs, 7 species of lianas, and 7 species of trees (Fig. 4). These 91 species of forage plants belong to 30 families (Fig. 5). Most of them belong to the Rosaceae, with 16 species, including herbaceous, shrubs, and trees. Such as species of Potentilla, Rubus, and Rosa. The next group is the Asteraceae, with 9 species, and all of them are herbs. There are 8 species of Fabaceae and Poaceae. The parts of forage plants consumed by black-boned sheep include aerial parts, leaves, fruits, roots, and flowers (Fig. 4). Of which the aerial part accounts for 55%. Next is the leaves, which make up for 34%. Followed by fruit, roots, and flowers, accounting for 5.5%, 3.3%, and 2.2%, respectively. Those forage plants can be divided into two types: wild and cultivated. Cultivated plants are mainly used as supplementary feed in winter when wild forage plants are scarce. On the other hand, considering the abundance of forage plants and the preference of black-boned sheep, Prinsepia utilis, Rosa multiflora, and the plants of Rubus, Berberis, and Yushania occupy dominated positions. Many forage plants have various uses and are used by local people as food, medicine, decoration, nectar source, and green fertilizer. Herbaceous plants account for the majority, which has a lot to do with such plants being easy to obtain and eat. Woody plants, especially trees, can only be consumed by sheep with the help of shepherds. Therefore, the local people have the habit of wearing a hatchet when grazing, to obtain the branches and leaves of the trees for the sheep to eat. Local people usually use the dry stems and leaves of these plants as the main source of feed when forage plants are lacking in the winter. This is because Fabaceae and Poaceae plants are generally recognized as suitable forage plants [61,62,63]. Key informants are very clear about the black-boned sheep’s dietary preferences. Some plants were repeatedly mentioned during the investigation. For instance, many key informants report that black-boned sheep especially like to eat the leaves of some shrubs, such as Rosa multiflora, P. utilis, and Berberis pruinosa (Fig. 6). The fruits of plants such as Sambucus adnata, Viburnum betulifolium, Elaeagnus umbellata, and Malus baccata fall on the ground when they mature. Sheep are very willing to consume them, it is very beneficial for them when it comes to supplementing nutrition (Fig. 6). The key informants emphasized that the phenomenon of black-boned sheep being strong and rarely getting sick is not only related to a large amount of exercise but also may be linked to the regular consumption of these forage plants. Therefore, they always tend to gravitate to places where these plants are abundant for grazing. Black-boned sheep’s preferred forage plants and some wild fruits used as black-boned sheep’s forage supplements (A Rosa multiflora Thunb.; B Prinsepia utilis Royle; C Berberis wilsonae Hemsl.; D Sambucus adnata Wall. ex DC.; E Malus rockii Rehd.; F Viburnum betulifolium Batal.) (Photographed by Chunlin Long between July 2019 and May 2021) The locals have a detailed understanding of the multifarious uses of various forage plants in the local, which is the experience they have accumulated in the long-term management of forests and grasslands. The key informants pointed out that many forage plants have diverse uses in the local area. For example, they use the fruits of Rubus plants like fruits, some people even pick the fruits of these plants to sell in the market. The locals also collect the tender leaves and shoots of plants such as Aralia chinensis, T. mongolicum, and P. utilis as wild vegetables. In Yunnan, many ethnic groups, including the Pumi people, traditionally use Rhododendron decorum flowers as food [64]. Besides, because local people have the habit of raising bees for honey, they recently discovered that the flowers of Astragalus sinicus and Vicia cracca are still effective sources of honey. Due to the plants’ high medicinal value, the locals also believe that these forage plants have a potential to develop into veterinary medicine [65, 66]. Black-boned sheep is a culturally important species in Pumi communities. There are many places named after sheep in Tongdian. For example, the largest ranch there is called Da yang chang (大羊场) , which means a special place for sheep activities. The Pumi consider sheep as a sacred object. The image of sheep can be seen everywhere in the life of the Pumi people (Fig. 7). In local communities, the most prominent of all sheep-related cultures is Gei Yang Zi (给羊子), which is a significant funeral ceremony of the Pumi people. Yang Zi is the Pumi’s cordial name for sheep. Gei Yang Zi is a traditional funeral ritual passed down by the Pumi people for generations, in the rich style of ancient nomadic tribes. In this ceremony, the sheep is the absolute protagonist. The ritual generally consists of three procedures: “Sacrificing sheep,” “Guiding the way,” and “burial.” On the second night of the death of the deceased, the family carefully selected a white and strong sheep (according to key figures, the black-boned sheep with a pure white coat is the most desirable), and the male and female are determined by the sex of the deceased. The sheep’s hooves, heads, and horns will be washed with spring water, but do not the body. Then, family members smoke the sheep with Rhododendron branches and leaves, remove any contamination, and thoroughly clean it. During this process, the chief priest was invited to sing “Tune for the Sheep.” To guide the way is to enable the dead to find their way back to their ancestors. At the beginning of the ceremony, the Pumi traditional religious figure Shi bie (释别) chanted the scriptures aloud. As the ceremony progressed, they fed the sheep with sacred objects such as wine and food. Under the guidance of Shi Bie, the sheep pointed out the migration route of his ethnic group or branch to the undead. This was so that he could return to the birthplace of his ancestors. The main message of the scripture chanted is: “Sheep are companions of the soul of the deceased, and are also their guides.” There is the companion of the sheep on the way home, and the deceased should not be afraid of any difficulties. Finish reciting the “Guided Path Scripture.” At dawn, the funeral procession sets off. At the front of the team is a horse-leader with a saddle on the horse, which symbolizes the deceased’s ride. After that, one person holds a torch to guide the deceased, but also to send fire to the deceased. In the end, 8 people brought the wooden coffin to the funeral. When several people carried the bamboo basket, there were eggs, slime, and other food items, including the indispensable sheep tied with paper. As a special cultural presentation, Gei Yang Zi is not only a symbol of ethnic ideology, but also a bond of ethnic spiritual reorganization. Therefore, it has profound cultural connotations. At the funeral of the Pumi people, giving the sheep is the most solemn ceremony. With the transformation of social life and the continuous improvement of national integration, many traditional rituals have lost their original functions. They are slowly being simplified and changed, or even disappearing. However, Gei Yang Zi is still a relatively complete traditional funeral custom in a minority of Pumi areas. It plays an integral part in the inheritance of spiritual culture and material culture of the ethnic group. Rather than saying that Gei Yang Zi is an ancient ritual, it is better to say that it is the soul of the Pumi people. This is because it is not only a medium for them to store and disseminate their traditional culture, but also a center for spiritual reorganization and memory identification. Therefore, in the future, while protecting the high-quality genetic resources of the black-bone sheep through local government propaganda, corporate conservation, and personal breeding, we must also realize the importance of protecting the traditional culture of the Pumi people on which the black-bone sheep depends. It is obvious that indigenous cultures cannot be passed down to future generations in their original forms [67, 68]. What we can do is to keep up with the times and add relevant content to it based on the original cultural heritage. Just as the Pumi people did, they replaced ordinary white sheep with black-boned sheep with pure white fur in the ceremony of Gei Yang Zi. On the one hand, it is the protection of precious genetic resources, and it is also the innovative development of traditional culture. Today, Gei Yang Zi has become a cultural symbol of the Pumi people. From this we can see their bravery, kindness, and their yearning for a better life in the future. Our research reveals the importance of interaction between folk traditional knowledge and conservation of black-boned sheep, a precious genetic resource. On the one hand, the traditional breeding techniques, grazing methods, and a variety of forage plants used by Pumi people are of high reference value for the government and individuals to establish breeding bases and high-quality alpine pastures to protect the germplasm resources of black-boned sheep. On the contrary, the traditional funeral ceremony related to black-boned sheep formed in the process of long-term grazing is of paramount significance to the inheritance of the traditional culture of the Pumi people. The Pumi people's rich traditional knowledge of black-boned sheep is the experience accumulated in animal grazing, forest and grassland management, and economic crop cultivation. These experiences may also have crucial reference significance for the conservation of genetic resources in other ethnic communities. Therefore, this study believes that the Pumi people’s rich traditional knowledge related to black-boned sheep is not only conducive to the protection of the species but is also essential to the livelihood development and cultural heritage of the community.Methods

Study area

Ethnobiological survey

Data analysis

Results and discussion

How to distinguish black-boned sheep and form a flock

Selection of grazing sites and use of black-boned sheep

Indigenous knowledge about black-boned sheep grazing

The diversity of plants consumed by black-boned sheep

Traditional culture related to black-boned sheep in the Pumi communities

Sacrificing sheep

Guiding the way

Burial

The role of Gei Yang Zi in the cultural identity of the Pumi

Conclusion

Availability of data and materials

All data, materials, and information are collected from the study sites.

References

Randolph TF, Schelling E, Grace D, Nicholson CF, Leroy JL, Cole DC, Demment MW, Omore A, Zinsstag J, Ruel M. Role of livestock in human nutrition and health for poverty reduction in develo** countries. J Anim Sci. 2007;85(11):2788–800. https://doi.org/10.2527/jas.2007-0467.

Ouachinou JMS, Dassou GH, Azihou AF, Adomou AC, Yédomonhan H. Breeders’ knowledge on cattle fodder species preference in rangelands of Benin. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2018;14(1):66. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-018-0264-1.

Osendarp SJM, Martinez H, Garrett GS, Neufeld LM, De-Regil LM, Vossenaar M, Darnton-Hill I. Large-scale food fortification and biofortification in low- and middle-income countries a review of programs, trends, challenges, and evidence gaps. Food Nutr Bull. 2018;39(2):315–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0379572118774229.

Khler-Rollefson I, Rathore HS, Mathias E. Local breeds, livelihoods and livestock keepers’ rights in South Asia. Trop Anim Health Pro. 2009;41(7):1061–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-008-9271-x.

Tamou C, Boer ID, Ripoll-Bosch R, Oosting SJ. Understanding roles and functions of cattle breeds for pastoralists in Benin. Livest Sci. 2018;210:129–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.livsci.2018.02.013.

Geng YF, Hu GX, Ranjitkar S, Wang YH, Bu DP, Pei SJ, Ou XK, Lu Y, Ma XL, Xu JC. Prioritizing fodder species based on traditional knowledge: a case study of mithun (Bos frontalis) in Dulongjiang area, Yunnan Province, Southwest China. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2017;13(1):24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-017-0153-z.

Martojo H. Indigenous Bali cattle is most suitable for sustainable small farming in Indonesia. Reprod Domest Anim. 2012;47(s1):10–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0531.2011.01958.x.

Köhler-Rollefson I. Indigenous practices of animal genetic resource management and their relevance for the conservation of domestic animal diversity in develo** countries. J Anim Breed Genet. 1997;114(1–6):231–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0388.1997.tb00509.x.

Cheng Z, Luo BS, Fang Q, Long CL. Ethnobotanical study on plants used for traditional beekee** by Dulong people in Yunnan, China. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2020;16(1):61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-020-00414-z.

Almeida AM, Ali SA, Ceciliani F, Eckersall PD, Hernández-Castellano LE, Han RW, Hodnik JJ, Jaswal S, Lippolis JD, McLaughlin M, Miller I, Mohanty AK, Mrljak V, Nally JE, Nanni P, Plowman JF, Poleti MD, Ribeiro DM, Zachut M. Domestic animal proteomics in the 21st century: a global retrospective and viewpoint analysis. J Proteomics. 2021;241: 104220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jprot.2021.104220.

He Z. Sustainable development of livestock and poultry scale-breeding based on integration control of resource losses and external environmental costs. Environ Prog Sustain. 2020;39(6):13528. https://doi.org/10.1002/ep.13528.

Marsoner T, Vigl LE, Manck F, Jaritz G, Tappeiner U, Asser E. Indigenous livestock breeds as indicators for cultural ecosystem services: a spatial analysis within the alpine space. Ecol Indic. 2017;94:55–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2017.06.046.

Gordon IJ, Pérez-Barbería FJ, Manning AD. Rewilding lite: using traditional domestic livestock to achieve rewilding outcomes. Sustainability. 2021;13(6):3347. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063347.

Smith WJ, Quilodrán CS, Jezierski MT, Sendell-Price AT, Clegg SM. The wild ancestors of domestic animals as a neglected and threatened component of biodiversity. Conserv Biol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13867.

Teutscherova N, Vázquez E, Sotelo ME, Villegas D, Arango J. Intensive short-duration rotational grazing is associated with improved soil quality within one year after establishment in Colombia. Appl Soil Ecol. 2021;159: 103835. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2020.103835.

Morris A. Animal welfare in a world concerned with food security. Vet Rec. 2011;169(3):65–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.d4299.

Stringer A. One health: improving animal health for poverty alleviation and sustainable livelihoods. Vet Rec. 2014;175(21):526–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.g6281.

Barker SFJ. Conservation and management of genetic diversity: a domestic animal perspective. Can J Forest Res. 2001;31(4):588–95. https://doi.org/10.1139/x00-180.

Bermejo JVD, Martínez MAM, Galván GR, Stemmer A, González FJN, Vallejo MEC. Organization and management of conservation programs and research in domestic animal genetic resources. Diversity. 2019;11(12):235. https://doi.org/10.3390/d11120235.

Blackburn HD. The national animal germplasm program: challenges and opportunities for poultry genetic resources. Poultry Sci. 2006;85(2):210–5. https://doi.org/10.1093/ps/85.2.210.

Hoffmann I. The global plan of action for animal genetic resources and the conservation of poultry genetic resources. World Poultry Sci J. 2009;65(2):286–97. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043933909000245.

Frewer LJ, Kole A, Kroon S, Lauwere CD. Consumer attitudes towards the development of animal-friendly husbandry systems. J Agr Environ Ethic. 2005;18(4):345–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-005-1489-2.

Delabouglise A, Boni MF. Game theory of vaccination and depopulation for managing livestock diseases and zoonoses on small-scale farms. Epidemics. 2019;30: 100370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epidem.2019.100370.

Bhuiyan MSA, Amin Z, Rodrigues KF, Saallah S, Shaarani SM, Sarker S, Siddiquee S. Infectious bronchitis virus (gamma corona virus) in poultry farming: vaccination, immune response and measures for mitigation. Vet Sci. 2021;8(11):273. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci8110273.

Vaarst M, Byarugaba DK, Nakavuma J, Laker C. Participatory livestock farmer training for improvement of animal health in rural and peri-urban smallholder dairy herds in **ja, Uganda. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2007;39(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-006-4439-8.

Narloch U, Drucker AG, Pascual U. Payments for agrobiodiversity conservation services for sustained on-farm utilization of plant and animal genetic resources. Ecol Econ. 2011;70(11):1837–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.05.018.

Megersa B, Biffa D, Niguse F, Rufael T, Asmare K, Skjerve E. Cattle brucellosis in traditional livestock husbandry practice in Southern and Eastern Ethiopia, and its zoonotic implication. Acta Vet Scand. 2011;53(1):24. https://doi.org/10.1186/1751-0147-53-24.

Vogl CR, Vogl-Lukasser B, Walkenhorst M. Local knowledge held by farmers in Eastern Tyrol (Austria) about the use of plants to maintain and improve animal health and welfare. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2016;12(1):40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-016-0104-0.

Simonetta B, Antonio RG, Iole MMD, Giovanna P. Traditional knowledge about plant, animal, and mineral-based remedies to treat cattle, pigs, horses, and other domestic animals in the Mediterranean island of Sardinia. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2018;14(1):50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-018-0250-7.

Li Q, Yang X. The origin, prosperity and changes of Chinese cattle culture. China Cattle Science. 2021;41(2):69–70. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1001-9111.2021.02.017

Sun W. Research progress of animal and poultry on genetic resource conservation and utilization in China. J Anim Sci Vet. 2001;20(1):8–10. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1004-6704.2001.01.003.

Zhao J, Lv YN, Yao JJ, Zhang XJ, Guo LY, Bai YY. Analysis on the main characteristics and achievements of the development of livestock and poultry seed industry in China. Chin Livest Poult Breed. 2019;15(5):25–7. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1673-4556.2019.05.021.

Wang QG, Wang HW, Guo ZY, Wang GF, Liu ZH, Yin YL. Strengthening protection of livestock and poultry genetic resources, promoting development of animal breed industry in China. Bull Chin Acad Sci. 2019;34(2):174–9. https://doi.org/10.16418/j.issn.1000-3045.2019.02.006.

Chang H. Advantage and crisis about domestic animal genetic resources in China. Guide To Chinese Poultry. 2003;20(10):14–16. https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/zgqydk200310004.

Li JJ, Li MX, Wang YJ. Problems and protection strategies of livestock and poultry genetic resources in China. J Northwest Univ Natl (Nat Sci). 2013;34(4):25–9. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1009-2102.2013.04.006.

Zhu GN, Li Q. Review to current research situation of local resources of livestock and poultry species in China. Anc Mod Agric. 2013. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1672-2787.2013.03.014.

Mao HM, Deng WD, Sun SR, Shu W, Yang SL. Studies on the specific characteristics of Yunnan black-boned sheep. J Yunnan Agric Univ. 2005;20(1):89–93. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1672-2787.2013.03.014.

Deng WD, Yang SL, Huo YQ, Gou X, Shi WX, Mao HM. Physiological and genetic characteristics of black-boned sheep (Ovis aries). Anim Genet. 2006;37(6):586–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2052.2006.01530.x.

Deng WD, ** DM, Gou X, Yang SL, Shi XW, Mao HM. Pigmentation in black-boned sheep (Ovis aries): association with polymorphism of the mc1r gene. Mol Biol Rep. 2008;35(3):379–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-007-9097-z.

He YD, Liu DD, ** DM, Yang LY, Tan YW, Liu Q, Mao HM, Deng WD. Isolation, sequence identification and expression profile of three novel genes rab2a, rab3a and rab7a from black-boned sheep (Ovis aries). Mol Biol. 2010;44(1):20–7. https://doi.org/10.1134/S0026893310010036.

Yonggang L, Shizheng G. A novel sheep gene, MMP7, differentially expressed in muscles from black-boned sheep and local common sheep. J Appl Genet. 2009;50(3):253–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03195680.

** black-boned sheep investigated by genome-wide single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Arch Anim Breed. 2020;63(1):193–201. https://doi.org/10.5194/aab-63-193-2020.

Chang XY, **e HB, Zhao K, Wei GC. Analysis of the nutritional components of black-boned sheep meat. Acta Nutrimenta Sinica. 2009;31(5):511-512,515. https://doi.org/10.3321/j.issn:0512-7955.2009.05.024.

Li W, Deng WD, Mao HM. Advance on melanin in the black-boned sheep. Acta Ecologiae Animalis Domastici. 2007;28(3):1–5. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1673-1182.2007.03.001.

Antons C. The role of traditional knowledge and access to genetic resources in biodiversity conservation in southeast Asia. Biodivers Conserv. 2010;19(4):1189–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-010-9816-y.

Wan IA, Tahir NM, Husain ML. Traditional knowledge on genetic resources: safeguarding the cultural sustenance of indigenous communities. Asian Soc Sci. 2012;8(7):184–91. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v8n7p184.

Applequist WL, Brown WL. Rights to plant genetic resources and traditional knowledge: Basic issues and perspectives by Susette Biber-Klemm and Thomas Cottier. Syst Bot. 2008;33(3):613–4. https://doi.org/10.1600/036364408785679888.

Li QJ. Development status and problems of Lan** Rongmao chicken. Chinese Livest Poult Breed. 2017;13(2):140. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1673-4556.2017.02.111.

Cai JR. Preliminary study on walnut germplasm resources in Lan** County. **andai Hortic. 2014;4(7):23–4. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1006-4958.2014.07.011.

Yang SH, Kang PD, Guo CC, Chen C, Xu FR, Tang WW, Xu ZZ. Investigation and agricultural resources analysis of the main populated area of Pumi national minority in Yunnan province. Agric Sci Technol. 2011;27(11):1691–8. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1009-4229-B.2011.11.034.

Kang PD, Xu ZZ, Chen C, Xu FR, Tang WW, Zhang EL, Yang SH. Investigation of agricultural botanic resources of Pumi national minority in Yunnan Province. Southwest China J Agric Sci. 2011;24(1):356–62. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1001-4829.2011.01.080.

Yang ZH. On origin of ethnic Pumi group and changes of its population. Soc Sci Yunan. 2003;6:101–4. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-8691.2003.06.023.

Huang HY, Wang X, Zhang PY, Zhao ZN. A study on the language and cultural inheritance of the minority nationalities without writing in Southwest China – Taking **uo, Pumi and Bai as examples. Art Lit Masses. 2015;2:205. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1007-5828.2015.02.167.

Zhao YY, Song FM. Tradition and modernity: A hundred years of livelihood change in a Pumi village. **nan Bianjiang Minzu Yanjiu. 2018. https://doi.org/10.13835/b.eayn.25.03.

Wang YJ, Xue DX. The effect of Pumi's traditional culture and resources management methods on their forest biodiversity. J Minzu Univ China (Nat Sci Ed). 2015;24(4):41–47. https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/zymzdxxb-zrkxb201504009.

He SH, Zhu WQ, Zhang XY. Analysis on the status quo of Lan** black-boned sheep and discussion on its development and utilization. Yunnan J Anim Sci Vet Med. 2013;2:18–20. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1005-1341.2013.02.016.

He ZL. Talking about the conservation and feeding management of Lan** black-boned sheep. Agric Technol. 2016;36(23):145–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2009.01392.x.

Heckathorn DD. Snowball versus respondent-driven sampling. Sociol Methodol. 2011;41(1):355–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9531.2011.01244.x.

Welch JK, Jorgensen DL, Fetterman DM. Participant observation: a methodology for human studies. Mod Lang J. 1991;74(1):87–8. https://doi.org/10.2307/327947.

Wu ZY, Raven PH, Hong DY eds. Flora of China. Bei**g: Science Press; and St. Louis: Missouri Botanical Garden Press; 2010.

Yang J, Luo JF, Gan QL, Ke LY, Zhang FM, Guo HR, Zhao FW, Wang YH. An ethnobotanical study of forage plants in Zhuxi County in the Qinba mountainous area of central China. Plant Divers. 2021;43(3):239–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pld.2020.12.008.

Larter NC, Nagy JA. Seasonal and annual variability in the quality of important forage plants on Banks Island, Canadian high arctic. Appl Veg Sci. 2010;4(1):115–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1654-109X.2001.tb00242.x.

Bahru T, Asfaw Z, Demissew S. Ethnobotanical study of forage/fodder plant species in and around the semi-arid Awash National Park, Ethiopia. J Forestry Res. 2014;25:445–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11676-014-0474-x.

Yang NT, Zhang Y, He LJ, Fan RY, Gou Y, Wang C, Wang YH. Ethnobotanical study on traditional edible sour plants of Bai nationality in Dali area. J Plant Resour Environ. 2018;27(2):93–100. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1674-7895.2018.02.12.

Aldayarov N, Tulobaev A, Salykov R, Jumabekova J, Kydyralieva B, Omurzakova N, Kurmanbekova G, Imanberdieva N, Usubaliev B, Borkoev B, Salieva K, Salieva Z, Omurzakov T, Chekirovb K. An ethnoveterinary study of wild medicinal plants used by the Kyrgyz farmers. J Ethnopharmacol. 2022;285: 114842. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2021.114842.

Nath A, Joshi SR. Chapter 15—Bioprospection of endophytic fungi associated with ethnoveterinary plants for novel metabolites. In: Fungi bio-prospects in sustainable agriculture, environment and nano-technology. 2021, p 375–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-821394-0.00015-9.

Muehlebach A. “making place” at the United Nations: indigenous cultural politics at the U.N. working group on indigenous populations. Cultur Anthropol. 2010;16(3):415–48. https://doi.org/10.1525/can.2001.16.3.415.

Archibald D. Indigenous cultural heritage: develo** new approaches and best practices for world heritage based on indigenous perspectives and values. Protecti Cultur Herita. 2020;9:1–13. https://doi.org/10.35784/odk.2084.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully thank the local people in Tongdian, Lan**, NW Yunnan, who provided valuable information and knowledge associated with black-boned sheep. Officials from Lan** County assisted our field work. Members of the Ethnobotanical Laboratory at Minzu University of China participated in the field surveys.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31761143001 and 31870316), the Minzu University of China (2020MDJC03), and the Biodiversity Survey and Assessment Project of the Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China (2019HJ2096001006).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CLL conceived and designed the study, and funded this study. YXF, CLL, ZC, and XH conducted the field surveys and collected the data. MA revised the manuscript and provided comments. CLL, ZC, and LB identified the plant species. YXF performed the literature review, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. CLL and MA edited the final version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All informants were asked for their free prior informed consent before interviews were conducted. Informants appearing in Fig. 2 agreed to publish the photos.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Fan, Y., Cheng, Z., Liu, B. et al. An ethnobiological study on traditional knowledge associated with black-boned sheep (Ovis aries) in Northwest Yunnan, China. J Ethnobiology Ethnomedicine 18, 39 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-022-00537-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-022-00537-5