Abstract

Purpose

To assess the reporting quality of published economic evaluations of the negotiated oncology drugs listed for China’s 2020 National Reimbursement Drug List (NRDL).

Methods

A comprehensive search was conducted to identify economic evaluation studies of negotiated oncology drugs listed in China’s 2020 NRDL using the PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, CNKI, SinoMed, and WanFang Database up to March 31, 2021. The Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) checklist scored the reporting quality between 0 and 100. A linear regression analysis was employed to examine the influence of various characteristics on the reporting quality scores.

Results

Eighty papers were included in the study, with the majority published during the past decade. Furthermore, more than half of the articles (57.5%, or 46 out of 80) were written in English. The average CHEERS score was 74.63 ± 12.75 and ranged from 43.48 to 93.75. The most inadequately reported items included choice of model, characterization of heterogeneity, and discussion, as well as currency, price date and conversion. Higher scores were associated with articles published from 2019 to 2021 and English publications.

Conclusion

The economic evaluation studies of negotiated oncology drugs listed in 2020 NRDL had moderate reporting quality. The Chinese economic evaluation publications could improve the reporting quality if the CHEERS checklist is consistently implemented. Also, the Chinese journals maybe explore introducing a reporting standard for economic evaluations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

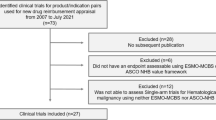

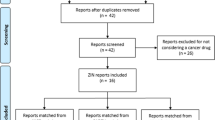

With the growing demand for medical care, health spending and pharmaceutical expenditure has increased rapidly over the past few decades [37,38,39,40,41,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,74,75,76,77,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106] is presented in Table 1. These studies involved 20 drugs (14 targeted therapies, 5 biologics, and 1 chemotherapy) out of 42 negotiated oncology drugs. In terms of the number of authors, studies of 1 ~ 3 authors were 21 (26.25%), 4 ~ 6 authors were 36 (45.00%), and more than 6 authors were 23 (28.75%). These studies were published between 2009 and 2021. Figure 2 shows that the number of studies published has grown during this period. There have been more publications in recent years: 15 (18.75%) studies were published between 2009 and 2015, 31 (38.75%) between 2016 and 2018, and 34 (42.5%) after 2018. Most studies were published in English in international journals (46 of 80 articles, 57.5%). The affiliation of the first authors is mainly hospital (62, 77.5%), and most of the first authors (63.75%) are from the eastern region, followed by the western region (22.5%).

Of these studies, most of them (83.75%) conducted the cost-utility analysis, and only one article conducted the cost-minimization analysis. Most (82.5%) of studies used modeling for their analyses, and 23.75 and 47.5% were health insurance and healthcare system perspective, respectively. In addition, two-fifth (38.75%) of studies used the 6-10-year time horizon for analysis, 20% used the 1 ~ 5 year, and 18.75% used a more than 10-year time horizon. Most studies were funded by the government (40%). Non-small cell lung cancer (46.25%), colorectal cancer (16.25%), and hepatocellular carcinoma (10%) were the most common tumor type for these studies.

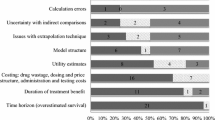

Figure 3 shows the proportion of the included studies scored as entirely adequate, partially, or not based on each CHEERS item. Several items demonstrated that less than half of the studies obtained full points, including the abstract, time horizon, discount rate, estimating resources and costs, currency, price date, and conversion, choice of model, heterogeneity, and discussion. In contrast, over 90% of the studies gave a clear title, setting and location, study perspective to estimate cost, and outcome indicators based on economic evaluation type.

Overall, the average CHEERS score of all articles was 17.68 ± 3.41 and ranged from 9.5 to 22.5 (Supplement Table 1). Converting to the 0-100 scale shown in Table 2, the average score of all articles was 74.63 ± 12.75 (range, 43.48–93.75). The average categorical scores for six main categories (title and abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion, and other) of the CHEERS checklist were 85.00 (SD = 15.20), 80.00 (SD = 24.65), 76.97 (SD = 11.63), 69.69 (SD = 19.87), 67.50 (SD = 24.00) and 59.69 (SD = 42.93), respectively. The mean reporting score of all articles in the title and abstract was the highest (85.00), followed by the introduction section (80.00). In contrast, the other section reported the lowest mean scores, including the source of funding, and conflicts of interest items.

Table 3 shows the CHEERS scores of all articles by the article characteristics.The Chinese articles’ scores were significantly lower than those published in English (P < 0.001). There was a significantly rising time trend in reporting quality scores: 68.81 (± 12.12) between 2009 and 2015), 73.69 (± 14.15) between 2016 and 2018, and 78.06 (± 10.78) after 2018 (trend testing P-value = 0.045). Regarding the author numbers, the articles with fewer authors assessed lower scores than those with more than six authors (P = 0.013). Regarding the type of economic evaluation, the mean score of articles reporting a CUA was 78.43 (± 9.27), which was significantly higher than those articles reporting a CEA and CMA (P < 0.001). The mean score of articles that used modeling design was 78.47 (± 9.12), significantly higher than the articles using prospective study design 49.40 (± 3.00), or the articles using retrospective study design 59.39 (± 13.14) (p < 0.001). The studies that used a longer time horizon for analysis had higher scores than those articles with a time horizon of less than one year (P < 0.001). In terms of source of funding, studies funded by the pharmaceutical industry had the highest mean scores (85.16 ± 6.34), followed by the government (79.58 ± 10.11), and studies with not mention funding sources (63.72 ± 10.55) had the lowest scores (P < 0.001). There are significant differences in the mean scores among articles that used different study perspectives, and the study did not mention that the study perspective had the lowest scores (P < 0.001).

Table 4 reports the influencing factors of CHEERS scores of included studies from regression analysis. Higher scores were associated with articles published between 2019 and 2021 year (P < 0.05) and English publications (P < 0.01). Studies without the disclosed source of funding and study perspective (P < 0.05) were statistically significant factors of lower scores.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to examine the reporting quality of economic evaluation studies focusing on the negotiated oncology drugs included in China’s NRDL for 2020. A drug price negotiation package should include an economic evaluation study. Transparent clear reporting and high-quality studies are essential for supporting decision-making in the process [107]. Furthermore, the Chinese National Health Insurance Administration does not disclose drug price negotiating dossiers, including economic evaluation evidence provided by manufacturers. We intended to review the currently available publications on this topic as a proxy for economic evaluation evidence from negotiations and evaluate them using CHEERS for reporting quality, and we hope to contribute to the renegotiation process in the future. The CHEERS checklist was one of the three most widely used quality assessment tools in pharmacoeconomic system review [108]. Many system reviews have used this checklist for quantitative assessment of economic evaluation since its publication [108, 109].

The overall mean score of reporting quality of economic evaluations in the present study was 17.68, and the scores ranged between 9.5 and 22.5, which showed less than 75% adherence to the CHEERS 2013 checklist. The CHEERS score was nearly the same as the reporting quality score of health economic evaluation research in India, Myanmar, Cambodia, and Laos, ranging between 17 to 17.8 [110]. Before our study, a study including pharmacoeconomic research from 2003 to 2014 in China reported a mean score of 18.7 assessed using the same CHEERS checklist, which had 1.02 higher than the score of our study [20]. The Jiehua Cheng et al. study showed that the average quality score of the included studies in China from 2006 to 2015 was 56.59 ± 16.90 [25], less than 74.63 ± 12.75 from our study. The reporting quality on China’s published economic evaluation studies of negotiated oncology drugs in 2020 latest NRDL may have been improved, but it is still lower than some studies.

The CHEERS scores can be divided into three categories: high quality for scores over 75, medium quality for scores between 50 and 75, and low quality below 50 [111, 25]. This difference may be because the editors of Chinese journals did not require authors to report standardized economic evaluations nor to supplement their details. For Chinese publications, the authors may be required to report each part of the economic evaluation based on China Guidelines for Pharmacoeconomic Evaluations. Furthermore, the Chinese standard checklist, similar to the CHEERS, could be developed to assess the Chinese economic evaluation studies.

There were some limitations in this study. Firstly, the CHEERS was intended to qualitatively evaluate the report quality of studies without specific rules for quantitative assessment [23, 119]. We may introduce a bias against publications that are not required to follow the CHEERS guideline. Secondly, some studies were published before the publication year of the CHEERS. In addition, the updated CHHERS 2022 was not used in our study because it had not been published at the time our study was completed. Moreover, compared with CHEERS 2013, the 2022 version contains additional content related to patients or service recipients, the general public, and community or stakeholder involvement and engagement; reporting and availability of a health economic analysis plan; and the description of distributional effects, among others [120]. These studies included in the article were also largely unreported. Finally, this study only assessed the report quality of included economic evaluation studies. Although this quality does not represent the quality of economic evaluation outcomes, it is also important to the decision-making process.

Conclusion

This study reveals moderate reporting quality of economic evaluations of negotiated oncology drugs listed in the 2020 NRDL. The number and reporting quality of economic evaluations of negotiated oncology drugs in mainland China have improved. However, most studies, especially those published in Chinese, do not fully report CHEERS items, significantly decreasing the studies’ transparency. Therefore, the reporting quality of economic evaluations conducted in mainland China should continue to improve. Also, the Chinese journals maybe explore introducing a reporting standard for economics evaluations, not only based on the CHEERS checklist.

Availability of data and materials

In this review all data are available from the referenced articles. The open access articles used for analysis during the current study are available from the corresponding author. The 24-item CHEERS evaluation applied on the 80 included economic evaluation studies is included in Supplementary material.

References

**ong Y, Cui Y, Zhang X. Pharmaceutical expenditure and total health-care expenditure in OECD countries and China: bidirectional Granger causality on the basis of health level. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2022;22(3):502–12.

Zhang X, Lai H, Zhang L, He J, Fu B, ** C. The impacts and unintended consequences of the nationwide pricing reform for drugs and medical services in the urban public hospitals in China. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):1058.

China NHCotPsRo. China’s health statistics yearbook. Bei**g: China Peking Union Medical University Press; 2021.

Yim EY, Lim SH, Oh MJ, Park HK, Gong JR, Park SE, Yi SY. Assessment of pharmacoeconomic evaluations submitted for reimbursement in Korea. Value Health. 2012;15(1 Suppl):104–10.

Si L, Xu L, Chen M, Jan S. Using strategic price negotiations to contain costs and expand access to medicines in China. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(1):e002256.

Notice of General Office of the National Health and Family Planning Commission on the results of national drug price negotiations. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2016-05/20/content_5075027.htm.

Zhou M, Wang H, Zeng X, Yin P, Zhu J, Chen W, Li X, Wang L, Wang L, Liu Y, et al. Mortality, morbidity, and risk factors in China and its provinces, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2019;394(10204):1145–58.

Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) Data Resources. https://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-2019.

Sun D, Li H, Cao M, He S, Lei L, Peng J, Chen W. Cancer burden in China: trends, risk factors and prevention. Cancer Biol Med. 2020;17(4):879–95.

Uyl-de Groot CA, McDonnell J, Ten Velde G, Radice D, Groen HJ. Cost-effectiveness of hypothetical new cancer drugs in patients with advanced small-cell lung cancer: results of a markov chain model. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2006;2(3):317–23.

Vokinger KN, Hwang TJ, Daniore P, Lee CC, Tibau A, Grischott T, Rosemann TJ, Kesselheim AS. Analysis of Launch and Postapproval Cancer Drug pricing, Clinical Benefit, and Policy Implications in the US and Europe. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(9):e212026.

Notice of the ministry of human resources and social security on the inclusion of 36 drugs in the category B of the national basic medical insurance, work injury insurance and maternity insurance drug list. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2017-07/19/content_5211741.htm#2.

Notice of the National Healthcare Security Administration on the Inclusion of 17 Oncology Drugs in the Category B of the National Basic Medical Insurance, Work Injury Insurance and Maternity Insurance Drug List. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2018-10/10/content_5328891.htm.

Notice of the National Healthcare Security Administration, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security on the Inclusion of the 2019 Negotiated Drugs in the Category B of the National Basic Medical Insurance, Work Injury Insurance and Maternity Insurance Drug List. http://www.nhsa.gov.cn/art/2019/11/28/art_38_2056.html.

Notice of the National Healthcare Security Administration, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security on the Inclusion of the 2020 Negotiated Drugs in the Category B of the National Basic Medical Insurance, Work Injury Insurance and Maternity Insurance Drug List. http://www.nhsa.gov.cn/art/2020/12/28/art_38_4219.html.

Hasegawa M, Komoto S, Shiroiwa T, Fukuda T. Formal implementation of cost-effectiveness evaluations in Japan: a Unique Health Technology Assessment System. Value Health. 2020;23(1):43–51.

“Thirteenth five-year Plan” to deepen the reform of the medical and health system. http://www.nhsa.gov.cn/art/2016/12/27/art_44_1110.html.

Franken M, Nilsson F, Sandmann F, de Boer A, Koopmanschap M. Unravelling drug reimbursement outcomes: a comparative study of the role of pharmacoeconomic evidence in dutch and swedish reimbursement decision making. PharmacoEconomics. 2013;31(9):781–97.

Sullivan SM, Wells G, Coyle D. What Guidance are economists given on how to present economic evaluations for policymakers? A systematic review. Value Health. 2015;18(6):915–24.

Ma H, Jian W, Xu T, He Y, Rizzo JA, Fang H. Quality of pharmacoeconomic research in China: a systematic review. Med (Baltim). 2016;95(41):e5114.

Si L, Yin M, Wang J, Yang S, Zhang J, Wei L. Evaluation of quality of pharmacoeconomic studies involved in traditional chinese medicine in China. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2021;21(5):1049–60.

National Healthcare Security. Administration (NHSA) and Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security (MOHRSS). http://www.nhsa.gov.cn/art/2020/12/28/art_37_4220.html.

Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, Carswell C, Moher D, Greenberg D, Augustovski F, Briggs AH, Mauskopf J, Loder E. Consolidated Health Economic evaluation reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement. Value Health. 2013;16(2):e1–5.

Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, Carswell C, Moher D, Greenberg D, Augustovski F, Briggs AH, Mauskopf J, Loder E. Consolidated Health Economic evaluation reporting Standards (CHEERS)--explanation and elaboration: a report of the ISPOR Health Economic evaluation publication Guidelines Good Reporting Practices Task Force. Value Health. 2013;16(2):231–50.

Cheng J, Zhang Y, Zhong A, Tian M, Zou G, Chen X, et al. Quality of health economic evaluations in Mainland China: a comparison of peer-reviewed articles in Chinese and in English. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2022;20(1):35–54.

Schmidt AF, Finan C. Linear regression and the normality assumption. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;98:146–51.

Bian S, Liu Y, Liu GG. Cost-effectivness analysis of second-line chemotherapy therapies for metastatic colorectal cancer. China J Pharm Econ. 2016;11(2):7–10.

Linghuan W, Jiahong H. Cost-effectiveness analysis of 2 dosage forms of Paclitaxel combined with carboplatin for first-line treatment of Advanced Ovarian Cancer. China Pharm. 2012;23(24):2268–70.

**aofeng F, Huiyu Y, Shan X. Cost-effectiveness analysis of paclitaxel combined with carboplatin in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer. Drug Evaluation Research. 2020;43(6):1108–11.

Han J, **ao D, Tan C, Zeng X, Hu H, Zeng S, Jiang Q, She L, Yao L, Li L, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of First-Line FOLFIRI Combined with Cetuximab or Bevacizumab in patients with RAS Wild-Type Left-Sided Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Control. 2020;27(1):1073274820902271.

Bai L, Zhang P, Zhou K, Liao W, Li Q. Cost-effectiveness analysis of First-Line Cetuximab Plus Leucovorin, Fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX-4) versus FOLFOX-4 in patients with RAS Wild-Type Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:10419–26.

Wang H, Huang L, Gao P, Zhu Z, Ye W, Ding H, Fang L. Cost-effectiveness analysis of cetuximab combined with chemotherapy as a first-line treatment for patients with RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer based on the TAILOR trial. BMJ Open. 2020;10(2):e030738.

Wen F, Yang Y, Zhang P, Zhang J, Zhou J, Tang R, Chen H, Zheng H, Fu P, Li Q. Cost-effectiveness of RAS screening before monoclonal antibodies therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer based on FIRE3 study. Cancer Biol Ther. 2015;16(11):1577–84.

Zhou J, Zhao R, Wen F, Zhang P, Tang R, Chen H, Zhang J, Li Q. Economic evaluation study (CHEER-compliant): cost-effectiveness analysis of RAS screening for treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer based on the CALGB 80405 trial. Med (Baltim). 2016;95(27):e3762.

Mei L, Wei Z, Guolong Z, Chunxiang Z. Cost-utility analysis of KRAS testing and cetuximab as first-line therapy for metastatic colorectal cancer. Chin J NewDrugs. 2018;27(24):2969–76.

Wu B, Yao Y, Zhang K, Ma X. RAS testing and cetuximab treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: a cost-effectiveness analysis in a setting with limited health resources. Oncotarget. 2017;8(41):71164–72.

**g T, Zhengyue L, **** Y, Zhuo W, Shen G. Economic analysis of Cetuximab in Therapy of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Chin J Pharmacoepidemiology. 2015;24(7):421–4.

Li WQ, Li LY, Chai J, Cui JW. Cost-effectiveness analysis of first-line treatments for advanced epidermal growth factor receptor-mutant non-small cell lung cancer patients. Cancer Med. 2021;10(6):1964–74.

Rui M, Li H. Cost-effectiveness of Osimertinib vs Docetaxel-bevacizumab in third-line treatment in EGFR T790M Resistance Mutation Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer in China. Clin Ther. 2020;42(11):2159–70.e2156.

Wen F, Zheng H, Zhang P, Liao W, Zhou K, Li Q. Atezolizumab and bevacizumab combination compared with sorafenib as the first-line systemic treatment for patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a cost-effectiveness analysis in China and the United states. Liver Int. 2021;41(5):1097–104.

Li X, Li W, Hou L. A trial-based cost-effectiveness analysis of Bevacizumab and Chemotherapy Versus Chemotherapy alone for Advanced Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer in China. Value Health Reg Issues. 2019;18:1–7.

Zheng H, **e L, Zhan M, Wen F, Xu T, Li Q. Cost-effectiveness analysis of the addition of bevacizumab to chemotherapy as induction and maintenance therapy for metastatic non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2018;20(3):286–93.

**aohong G, Yuanxin G, Haoyang D. Cost-effectiveness of fi rst-line chemotherapy with bevacizumab for patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Cent South Pharm. 2014;12(9):925–8.

Zhang PF, Wen F, Zhou J, Huang JX, Zhou KX, Wu QJ, Wang XY, Zhang MX, Liao WT, Li Q. Cost-effectiveness analysis of capecitabine plus bevacizumab versus capecitabine alone in elderly patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer from chinese societal perspective. Clin Transl Oncol. 2020;22(1):103–10.

Fei Z, Xu T, Li M, Chen T, Li L, Qiu X, Chen C. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness analysis of nimotuzumab for the radiotherapy of locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Radiat Oncol. 2020;15(1):230.

Chen W, Jiang Z, Shao Z, Sun Q, Shen K. An economic evaluation of adjuvant trastuzumab therapy in HER2-positive early breast cancer. Value Health. 2009;12(Suppl 3):82–4.

Wu B, Ye M, Chen H, Shen JF. Costs of trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy for HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastroesophageal junction cancer: an economic evaluation in the chinese context. Clin Ther. 2012;34(2):468–79.

Wei C, Sujian X, He L, Yongqing L, Zhan Z. A cost-effectiveness analysis of adjuvant trastuzumab regimens in HER2-Positive early breast cancer. Chin Pharm J. 2017;52(8):696–701.

Wenbo G, Juyang X, Han Z, yu S, dandan G. Evaluationon Pharmacoeconomicof trastuzumab in the adjuvant treatment for early HER2- positive breast cancer. Chin Health Econ. 2017;36(11):72–5.

Peipei R, **chun S, Yue W. Cost-effectiveness analysis of trastuzumab combined with chemotherapy for Her-2 positive advanced gastric cancer. China Pharm. 2015;26(5):577–9.

**aoying D, **aohong Z, Jie C, Guohao L. Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of Trastuzumabin adjuvant treatment for breast cancer. Pharm Today. 2017;27(8):560–3.

**g**g H, **aolei Y, Yue Z. Cost-efficacy analysis and influence on compliance of trastuzumab for treating HER-2 positive breast cancer. Drug ï¼²esearch. 2016;25(4):35–7.

Xu Q, Yuanyuan L, Jie**g Z, Jian L, Qingyu L, Lingya C, Ying L, Changchen S, Yangling L, Wei Y. Cost-effectiveness of paclitaxel, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide and trastuzumab versus docetaxel, cisplatin and trastuzumab in new adjuvant therapy of breast cancer in china. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2021;19(1):11.

Qiao** X, Jie** Z, Jian L, Lingya C, Ying L, Changcheng S, Yangling L, Biqin T, Wei Y. Cost-effectiveness analysis of two neoadjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer patient. Chin J Mod Appl Pharm. 2019;36(8):985–92.

Fenghao S, Rui M, Zi**g W, Mingjun R, Ye S, Aixia M. Cost-effectiveness analysis of applying camrelizumab as second-Line therapy for the treatment of advanced hepa- tocellular carcinoma. Chin Health Econ. 2021;40(2):62–5.

Hao W, Chenxin Z, Li L, Weihong G. Cost-effectiveness analysis of osimertinib and gefitinib /erlotinib as the first-line therapy for EGFï¼²-mutated advanced non-small-cell Lung cancer. Herald Med. 2020;39(12):1689–96.

Cai H, Zhang L, Li N, Chen S, Zheng B, Yang J, Weng L, Liu MB. Cost-effectiveness of osimertinib as first-line treatment and sequential therapy for EGFR mutation-positive non-small cell lung cancer in China. Clin Ther. 2019;41(2):280–90.

Wang S, Peng L, Li J, Zeng X, Ouyang L, Tan C, Lu Q. A trial-based cost-effectiveness analysis of erlotinib alone versus platinum-based doublet chemotherapy as first-line therapy for eastern asian nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(3):e55917.

Gu X, Zhang Q, Chu YB, Zhao YY, Zhang YJ, Kuo D, Su B, Wu B. Cost-effectiveness of afatinib, gefitinib, erlotinib and pemetrexed-based chemotherapy as first-line treatments for advanced non-small cell lung cancer in China. Lung Cancer. 2019;127:84–9.

Qian K, Zheng Y. Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of EGFï¼²-TKIs in the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Chin J Drug Eval. 2013;30(5):305–8.

Qian K, Danni X, Zheng Y. Cost-effectiveness analysis of EGFï¼²-TKIs in the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Chin J Drug Eval. 2013;30(6):377–80.

Wen F, Zheng H, Zhang P, Hutton D, Li Q. OPTIMAL and ENSURE trials-based combined cost-effectiveness analysis of erlotinib versus chemotherapy for the first-line treatment of asian patients with non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer. BMJ Open. 2018;8(4):e020128.

Liying O. Cost - effectiveness evaluation of two first - line chemotherapy regimens in advanced non - small cell lung cancer patients with epidermal growth factor receptor mutation. Chin J New Drugs Clin Remedies. 2016;35(2):138–44.

MA Y, Huang Y, Zhao H, Liu J, Chen L, Wu H. The cost-effectiveness analysis of gefitinib or Erlotinib in the treatment of advanced EGFR mutant non-small cell lung cancer patients. Chin J Lung Cancer. 2013;16(4):203–10.

Liangyu B, Min L, Beibei C, Huifang L, Lili H, Hongzhi Z, Weijie Z, Qingxia F, Liuxing W, **aobing C, et al. Clinical effect and pharmacoeconomics analysis of EGFR-TKI in the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Basic Clin Oncol. 2016;29(2):143–6.

Yun Z, Meiling Z. Analysis of the direct medical cost of targeted therapy for non-small cell lung cancer. Chin J Clin Pharm. 2018;27(3):167–71.

LI W, Qian L, Li W, Chen X, He H, Tian H, Zhao Y, Wang X, Cui J. Cost-effectiveness analysis of different sequences of osimertinib administration for epidermal growth factor receptor-mutated non-small-cell lung cancer. Exp Ther Med. 2021;21(4):343.

Wu B, Gu X, Zhang Q. Cost-effectiveness of osimertinib for EGFR mutation-positive non-small cell lung cancer after progression following first-line EGFR TKI therapy. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(2):184–93.

Wu B, Gu X, Zhang Q, **e F. Cost-effectiveness of osimertinib in treating newly diagnosed, advanced EGFR-mutation-positive non small cell lung cancer. Oncologist. 2019;24(3):349–57.

Yihua Y, Yue Y, Yuanqiu P. Cost-effectiveness analysis of osimertinib as first-line therapy in locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC with an EGFR mutation. Chin J New Drugs Clin Remedies. 2021;40(3):205–9.

Guan HJ, Liu GD, **e F, Sheng YN, Shi LW. Cost-effectiveness of osimertinib as a second-line treatment in patients with EGFR-mutated advanced non-small cell lung cancer in China. Clin Ther. 2019;41(11):2308–20.

Hai**g G, Guoen L, Yanan S, Yanan W, Hongchao L. Cost-effectiveness of osimertinib in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients. China Health Insur. 2018(5):46–54.

Mei Z, Bin W, Fengbo W, Ting X. Cost-effectiveness analysis of anlotinib for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Herald of Medicine. 2020;39(2):172–5.

** Z, Lihong R, Dong L, Ziyun L, ** W, Beibei Y, Fengli J. Cost-effectiveness analysis of anlotinib in treating advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Chin J New Drugs Clin Remedies. 2020;39(6):380–4.

Haiying D, Sisi K, Jiao S, Gaoqi X, Chaoneng H, ** H. Cost-effectiveness analysis of anlotinib hydrochloride for treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Health Econ Res. 2020;37(5):19–22.

Li H, Lai L, Wu B. Cost effectiveness of ceritinib and alectinib versus crizotinib in first-line anaplastic lymphoma kinase positive advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Drug Investig. 2020;40(2):183–9.

Liu M, Zhang L, Huang Q, Li N, Zheng B, Cai H. Cost-effectiveness analysis of ceritinib and alectinib versus crizotinib in the treatment of anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:9195–202.

Li Z, Caicun Z, Jun Z, Jie H, **aorong D, Jian M. Cost-effectiveness study of alectinib compared with crizotinib in first-line treatment for ALK positive advanced NSCLC in China.Chin Health Insur 2019(12):56–62.

Huang M, Tian Y, He M, Liu J, Ren L, Gong Y, Peng F, Wang Y, Ding Z, Wang J, et al. Crizotinib versus chemotherapy: a real-world cost-effectiveness study in China. J Comp Eff Res. 2020;9(2):93–102.

Weicheng L, Bao** D, **%2CD&author=**aoquan%2CL&author=Tao%2CL"> Google Scholar

Lifeng M, **anxi G, Yanru H, Ling H, Peipei R, Benhong Z. Cost-effectiveness analysis of crizotinib in first-line treatment of ALK-positive non-small cell lung cancer. China Pharmacist. 2020;23(6):1119–23.

Longfen Z, Qi-shu H, Lingling Q, **uqin L, Hongfu C. Cost-effectiveness analysis of ceritinib versus alectinib for first-line treatment of ALK-positive advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Strait Pharm J. 2019;31(8):86–9.

Peng Y, Ma F, Tan C, Wan X, Yi L, Peng L, Zeng X. Model-based economic evaluation of ceritinib and platinum-based chemotherapy as first-line treatments for advanced non-small cell lung cancer in China. Adv Therapy. 2019;36(11):3047–58.

Zhao RC, Zhou J, Wei YG, Liu F, Chen KF, Li Q, Li B. Cost-effectiveness anallysis of transcatheter irterOaV chernoernboOlization with or without sorafenib for the treatment of unresectablie hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2017;16(5):493–8.

Zhang P, Yang Y, Wen F, Wheeler J, Fu P, Li Q. Cost-effectiveness analysis of antiviral therapy in patients with advanced hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sorafenib. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31(12):1978–85.

Qin S, Kruger E, Tan SC, Cheng S, Wang N, Liang J. Cost-effectiveness analysis of FOLFOX4 and sorafenib for the treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in China. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2018;16:29.

Zhang P, Yang Y, Wen F, He X, Tang R, Du Z, Zhou J, Zhang J, Li Q. Cost-effectiveness of sorafenib as a first-line treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;27(7):853–9.

Zhang P, Wen F, Li Q. FOLFOX4 or sorafenib as the first-line treatments for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Dig Liver Dis. 2016;48(12):1492–7.

Chen S, Peng Z, Wei M, Liu W, Dai Z, Wang H, Mei J, Cheong M, Zhang H, Kuang M. Sorafenib versus transarterial chemoembolization for advanced-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: a cost-effectiveness analysis. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):392.

**nke Z, **g W, Aixia M. Cost-effectiveness of sequential therapies of sunitinib and sorafenib in metastatic ï¼²enal cell carcinoma. Chin J Drug Evaluation. 2013;30(3):178–83.

Huaiyong Y, Long Y, Youwei X, Xuan W. Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of sunitinib for the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Chin Pharm. 2012;23(26):2401–4.

Guan X, Li H, **ong X, Peng C, Wang N, Ma X, Ma A. Cost-effectiveness analysis of fruquintinib versus regorafenib as the third-line therapy for metastatic colorectal cancer in China. J Med Econ. 2021;24(1):339–44.

Chen HD, Zhou J, Wen F, Zhang PF, Zhou KX, Zheng HR, Yang Y, Li Q. Cost-effectiveness analysis of apatinib treatment for chemotherapy-refractory advanced gastric cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017;143(2):361–8.

Bai Y, Xu Y, Wu B. Cost-effectiveness and budget impact analysis of apatinib for advanced metastatic gastric cancer from the perspective of health insurance system. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2017;2017:2816737.

Zhang P-F, **e D, Li Q. Cost-effectiveness analysis of fruquintinib as third-line treatment for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Tumori J. 2020;106(5):400–5.

Peng Z, Hou X, Huang Y, **e T, Hua X. Cost-effectiveness analysis of fruquintinib for metastatic colorectal cancer third-line treatment in China. Bmc Cancer. 2020;20(1):990.

Wu B, Liu M, Li T, Lin H, Zhong H. An economic analysis of high-dose imatinib, dasatinib, and nilotinib for imatinib-resistant chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia in China: a CHEERS-compliant article. Med (Baltim). 2017;96(29):e7445.

Li N, Zheng B, Cai HF, Yang J, Luo XF, Weng LZ, Zhan FM, Liu MB. Cost effectiveness of imatinib, dasatinib, and nilotinib as first-line treatment for chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia in China. Clin Drug Investig. 2018;38(1):79–86.

Wei X, Nan G, Li M, Zhenzhen D. Cost utility analysis of high dose imatinib, dasatinib and nilotinib in treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia. Chin J Hosp Pharm. 2017;37(19):1974–8.

Lin C, Min Y, Guohua C. Phamacoeconomics evaluation of nilotinib and dasatinib in second-line treament of chronic mycloid leukemia therapy. Tumor. 2016;36(6):698–704,710.

Ling G, Chengfeng H, Yuehua L, Yansui Y. Cost-utility analysis of nilotinib versus high-dose Imatinib for the second-line treatment of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Chin Health Econ. 2018;37(5):57–61.

Cai HF, Zhang LF, Li N, Zheng B, Liu MB. Cost-effectiveness analysis on binary/triple therapy on the basis of ixazomib or bortezomib for refractory or relapsed multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2019;60(12):2951–9.

Wu B, Chen H, Shen J, Ye M. Cost-effectiveness of adding Rh-Endostatin to first-line chemotherapy in patients with Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer in China. Clin Ther. 2011;33(10):1446–55.

Lu S, Yu Y, Fu S, Ren H. Cost-effectiveness of ALK testing and first-line crizotinib therapy for non-small-cell lung cancer in China. Plos One. 2018;13(10):e0205827.

Lu S, Zhang J, Ye M, Wang B, Wu B. Economic analysis of ALK testing and crizotinib therapy for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Pharmacogenomics. 2016;17(9):985–94.

Guan H, Sheng Y, Guo W, Han S, Shi L. Cost-effectiveness of Alectinib for patients with untreated ALK-Positive Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer in China. Adv Ther. 2019;36(5):1114–25.

Monten C, Veldeman L, Verhaeghe N, Lievens Y. A systematic review of health economic evaluation in adjuvant breast radiotherapy: quality counted by numbers. Radiother Oncol. 2017;125(2):186–92.

Min C, Xue M, Haotian F, Jialian L, Lingli Z. An overview of the characteristics and quality assessment criteria in systematic review of pharmacoeconomics. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(2):e0246080.

Hiligsmann M, Evers SM, Ben Sedrine W, Kanis JA, Ramaekers B, Reginster JY, Silverman S, Wyers CE, Boonen A. A systematic review of cost-effectiveness analyses of drugs for postmenopausal osteoporosis. PharmacoEconomics. 2015;33(3):205–24.

Karekar S, Shetty Y. Assessment of the quality and trend of reporting of health economic evaluation research in India. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2021;21(4):595–9.

Geng J, Yu H, Mao Y, Zhang P, Chen Y. Cost effectiveness of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors for type 2 diabetes. PharmacoEconomics. 2015;33(6):581–97.

Wong CKH, Liao Q, Guo VYW, **n Y, Lam CLK. Cost-effectiveness analysis of vaccinations and decision makings on vaccination programmes in Hong Kong: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2017;35(24):3153–61.

Flemming J, Chojecki D, Tjosvold L, Paulden M, Armijo-Olivo S. Quality of reporting of economic evaluations in rehabilitation research: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44(11):2233–40.

Soares HP, Daniels S, Kumar A, Clarke M, Scott C, Swann S, Djulbegovic B. Bad reporting does not mean bad methods for randomised trials: observational study of randomised controlled trials performed by the radiation therapy oncology group. BMJ. 2004;328(7430):22–4.

Dechartres A, Trinquart L, Atal I, Moher D, Dickersin K, Boutron I, Perrodeau E, Altman DG, Ravaud P. Evolution of poor reporting and inadequate methods over time in 20 920 randomised controlled trials included in Cochrane reviews: research on research study. BMJ. 2017;357:j2490.

Aguiar PM, Lima TM, Storpirtis S. Systematic review of the economic evaluations of novel therapeutic agents in multiple myeloma: what is the reporting quality? J Clin Pharm Ther. 2016;41(2):189–97.

Hay JW, Smeeding J, Carroll NV, Drummond M, Garrison LP, Mansley EC, Mullins CD, Mycka JM, Seal B, Shi L. Good research practices for measuring drug costs in cost effectiveness analyses: issues and recommendations: the ISPOR drug cost Task Force report–part I. Value Health. 2010;13(1):3–7.

O’Donnell H, McCullagh L, Barry M, Walsh C. The Interaction between price negotiations and heterogeneity: implications for economic evaluations. Med Decis Making. 2020;40(2):144–55.

Fayanju OM, Haukoos JS, Tseng JF. CHEERS reporting guidelines for economic evaluations. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(7):677–8.

Husereau D, Drummond M, Augustovski F, de Bekker-Grob E, Briggs AH, Carswell C, Caulley L, Chaiyakunapruk N, Greenberg D, Loder E, et al. Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards 2022 (CHEERS 2022) statement: updated reporting guidance for health economic evaluations. Value Health. 2022;25(1):3–9.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank China Medical Board (CMB) for their financial support for this project. The content of this publication represents the views of the authors and it is their sole responsibility; it can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the China Medical Board (CMB).

Funding

The study was supported by China Medical Board (CMB), Grant 19–318, A Demonstration Program on Health Technology Assessment in China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LL contributed to formulating the idea, designing the study, literature search, quality assessment of the included studies, data extraction, draft of the article, revising and editing the article. ZJ contributed to literature search, quality assessment of the included studies, and data extraction. FL screened, appraised and extracted data, and assisted with quality assessment of the included studies. YW, JM and YC contributed to formulating the idea, designing the study, data interpretation, revising and editing the article for the important contents to be included. YY, SL and LS contributed to assist with the interpretation of results and the revising of the manuscript. All authors read and accepted the last version of manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Supplementary Table 1. The 24-item CHEERS evaluation applied on the 80 included economic evaluation studies.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, L., Jiang, Z., Li, F. et al. Were economic evaluations well reported for the newly listed oncology drugs in China’s national reimbursement drug list. BMC Health Serv Res 22, 1475 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08858-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08858-7