Abstract

Background

The National Health and Family Planning Commission of China has issued more than 400 clinical pathways to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of medical care delivered by public hospitals in China. The aim of our study is to determine whether patient care is compliant with national clinical pathways in public general hospitals of Pudong New Area in Shanghai.

Methods

We identified the clinical pathways established by the National Health and Family Planning Commission of China for 5 common conditions (community-acquired pneumonia, acute myocardial infarction (AMI), heart failure, cesarean section, type-2 diabetes). We randomly selected patients with each condition admitted to one of 7 public general hospitals in Pudong New Area in China in January, 2013. We identified key process indicators (KPIs) for each pathway and, based on chart review for each patient, determined whether the patient’s care was compliant for each indicator. We calculated the proportion of care which was compliant with clinical pathways for each indicator, the average proportion of indicators that were met for each patient, and the proportion of patients whose care was compliant for all measures. For selected indicators, we compared compliance rates among hospitals in our study with those from other countries.

Results

Average compliance rates across the KPIs for each condition ranged from 61 % for AMI to 89 % for pneumonia. The percent of patient receiving fully compliant care ranged from 0 for AMI and heart failure to 39 % for pneumonia. Compared to the compliance rate for process indicators in the hospitals of other countries, some rates in the hospitals that we audited were higher, but some were lower.

Conclusions

Few patients received care that complied with all the pathways for each condition. The reasons for low compliance with national clinical pathways and how to improve clinical quality in public hospitals of China need to be further explored.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Ensuring that hospitals consistently provide high quality care is a challenge facing policymakers and hospital administrators around the world. The quality of hospital care is an important issue for policy makers in China as patients are increasingly demanding higher quality care. A key component of national policies intended to improve quality of care has been the development and use of clinical pathways.

As in many other countries, the use of clinical pathways has increased rapidly in China in recent years. The National Health and Family Planning Commission (NHFPC, previously called “Ministry of Health”) of China has issued more than 400 clinical pathways [1]. Despite the emphasis placed on the use of pathways, there is little evidence on the extent to which Chinese hospitals provide care consistent with these pathways [2].

Clinical guidelines and pathways

Clinical guidelines are recommendations on the appropriate treatment and care of people with specific diseases and conditions [3]. Clinical pathways, in contrast, support the translation of clinical guidelines into local practice by identifying the specific steps necessary to translate the clinical guideline into practice in a particular local environment [4]. By linking evidence to clinical practice, the use of clinical pathways is intended to optimize patient outcomes and increase clinical efficiency [4].

In China, national medical associations generally create clinical guidelines and the NHFPC translates the guidelines into clinical pathways. In 2012, the NHFPC required every tertiary- and secondary-level hospital in China to implement at least 60 clinical pathways, with at least 40 from among the over 400 established by the NHFPC, although the hospitals may customize the pathways for their patients. In this study, we examine the extent to which the care provided by public hospitals in Shanghai is consistent with national clinical pathways.

Effects of clinical guidelines and pathways

Studies have documented an association between the use of clinical guidelines and pathways and positive outcomes including the provision of high-quality, cost-effective care, greater patient and staff satisfaction, and better resource management in a variety of clinical contexts [4–7]. Other studies have documented that the adoption of clinical pathways can reduce length of stay and decrease medical cost [8–10].

In this study, we document the clinical pathways established by the NHFCP for five clinical conditions: community-acquired pneumonia (“pneumonia”), AMI, heart failure, cesarean section, type-2 diabetes. Clinical guidelines or pathways have been shown to be effective in these clinical contexts. Guideline-concordant therapy for community-acquired pneumonia is associated with improved health outcomes and the use of fewer resources [11, 12]. Compliance with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) guidelines is associated with lower inpatient mortality [13–15] and the implementation of a clinical pathway for heart failure was associated with improvements in care processes as well as reduced length of stay and hospital charges [16, 17]. A study of the implementation of National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidance regarding caesarean section documented lower rates of surgical site infection following caesarean section [18]. In the context of diabetes, the implementation of a process improvement effort using practice guidelines resulted in greater compliance with recommended HbA1c, lipid, blood pressure, and foot checks, leading to better control of blood pressure and lower body mass index (BMI) [19]. Despite the potential for adherence to clinical guidelines to reduce mortality and morbidity and decrease healthcare costs, there is substantial evidence that adherence to guidelines in clinical practice is often poor [13, 14, 20–22].

In our analysis, we measure the extent to which the care patients received was compliant with the national clinical pathways for these conditions in public general hospitals of Pudong New Area in Shanghai. We identify key process indicators (KPIs) for each condition based on the clinical pathways and then determine whether the care of randomly selected patients with each condition was consistent with these indicators. We also compare performance on several clinical pathways with results from studies of other countries.

Our study is the first to document the extent to which public hospitals in China are adhering to national guidelines. The study provides important baseline information on the delivery of health care in Chinese public hospitals and the potential for improvements in health care quality.

Methods

Survey sample

We studied physician compliance with the national clinical pathways in all seven public, general hospitals in Pudong New Area of Shanghai. We chose to study 5 conditions: pneumonia, AMI, heart failure, cesarean section, and type-2 diabetes. These conditions were among the top ten in patient volume in all the surveyed hospitals and had national clinical pathways published by NHFPC [23].

Using hospital information systems, we identified all patients with a given diagnosis, based on inpatient international classification of diseases (ICD-10 or ICD-9) codes, admitted to each hospital during 2012 for each condition. To ensure that the sample was evenly distributed throughout the year, we randomly selected the first two inpatient admissions with an odd patient number for each condition in each month. If a hospital admitted fewer than 24 patients for a particular condition in 2012, then all the medical records for this condition were extracted for this hospital.

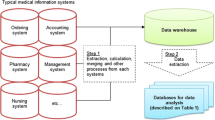

Data sources

We developed an audit chart for each of the five conditions based on the clinical pathways published by NHFPC. The audit chart identified the key process components in the clinical pathway, focusing on those both that were important determinants of quality of care and for which data was likely to be available in medical records. We then extracted data from the medical records corresponding to each item in the audit chart for each patient.

To ensure the quality and consistency of chart audit, we trained five researchers on the meanings of each item on the checklist and how to audit each chart. The researchers then observed two experts auditing charts to assess compliance for heart failure and cesarean section pathways in one hospital and subsequently audited the same charts the experts audited. The consistency between the experts and the researchers for these two conditions was 87 %.

For each admission, we also collected data on patient demographics and health status as well as some financial information from the hospital information systems (HIS) of the surveyed hospitals.

Selection of key process indicators

The national clinical pathways are very detailed and when we abstracted data, we tried to gather information on each step. When reporting the results, we chose to focus on the more clinically meaningful components of each pathway (see Additional file 1). For example, in the pneumonia pathway, we focused on severity assessment and corresponding treatment, appropriate use of antibiotics, health education, and appropriate length of stay. We did not include appropriateness of admission as a KPI. Similarly, for AMI, we focused on timely treatment and evaluation of left ventricular function, appropriate use of medicine (such as aspirin/clopidogrel, β-blocker, ACEI/ARB, statins), reperfusion therapy, thrombolytic therapy and health education, because they are life-saving and important for secondary disease preventions. We did not include length of stay for AMI due to the potential for differences across patients in appropriate length of stay.

Data analysis

We coded hospitals as compliant for an indicator only if the information was recorded in the medical record and the care was consistent with the clinical pathway or if the medical record included a reasonable explanation for not being compliant. For each KPI, we calculated the proportion of patients who received compliant care.

From this information, we also calculated two patient-level measures of compliance: 1) whether the patient received pathway compliant care for all indicators (fully compliant care) and 2) the proportion of KPIs that were met for the patient. We used these patient-level measures to calculate the proportion of patients receiving fully compliant care (full compliance rate) for each condition and the average of the proportion of KPIs that were met over all patients with a given condition (average compliance rate).

Ethics approval

This study was approved by Institutional Review Board, School of Public Health, Fudan University (IRB#2012-11-0383).

Consent statement

N/A for this retrospective study.

Results

The numbers of medical records audited across all hospitals in the study were 151, 97, 145, 146 and 137 for pneumonia, AMI, heart failure, caesarean section, and type-2 diabetes, respectively (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5).

Compliance rates

Compliance rates for the KPIs for pneumonia ranged from 70 to 100 %. All the patients with pneumonia had appropriate length of stay according the pathway, but the compliance rate for “Severe patients (defined as oxygen saturation < 92 %) received blood gas analysis” was 70 %. The proportion of patients who received initial antibiotics properly within 4 h of hospital arrival in our study was 92 % (Table 1).

The compliance rates for the AMI KPIs ranged from 0 to 94 %. The lowest three compliance rates were for “Reassessment of patient condition within 1 week before discharge” (0 %), “PCI(percutaneous coronary intervention) within 90 min of admission” (0 %), and “Thrombolytic therapy within 30 min of admission” (5 %). In addition, the compliance rate for reperfusion therapy for STEMI(ST - segment elevation myocardial infarction) or LBBB(left bundle branch block) patients was 75 % and for using β-blocker within 24 h of admission was 67 %. Eighty percent, 61 and 65 % of AMI patients were advised to continue to use aspirin, β-blocker, and ACEI(angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor)/ARB (angiotensin receptor antagonist) after discharge, respectively. Forty-eight percent of inpatients without a contraindication of heart failure did not receive β-blockers (Table 2).

The compliance rates for the heart failure KPIs varied widely, ranging from 1 to 100 %. Rates were lowest for “Assessment of left ventricular function 1 week prior to discharge” (1 %) and for “Use of β-blockers only for patients with chronic heart failure” (20 %). In addition, the proportion of inpatients not using β-blockers without a documented reason was 48 % (Table 3).

The compliance rates for the caesarean section KPIs ranged from 62 to 100 %. The three KPIs with the lowest compliance rates were “The timeliness of operation time” (62 %), “Prophylactic use of first generation cephalosporin antibiotics” (62 %), and “Delivery within 2 days of admission” (62 %). The compliance rate for appropriate use of oxytocin (10ug or 20ug) during cesarean section was quite high (81 %) (Table 4).

The compliance rates for the type-2 diabetes KPIs ranged from 39 to 100 %. The three KPIs with the lowest compliance rates were “Nerve system examination” (39 %), “Glycosylated serum protein (Fructosamine) test” (55 %), and “Oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) and insulin or C peptide release test” (58 %). The compliance rate for HbA1c test was 91 % (Table 5).

The compliance rates for health education for all five diseases were relatively high (above 86 %) in the surveyed hospitals (Tables 1-5).

Full and average compliance rates

The proportion of patients who received fully compliant care was low for each of the five conditions in the surveyed hospitals, ranging from 0 % (AMI and heart failure) to 39 % (pneumonia). The average compliance rates of the KPIs ranged from 61 % (AMI) to 89 % (pneumonia). The compliance rates among the 5 selected conditions were significantly different (Table 6).

Discussion

Compliance rates for the five conditions

The objectives of the use of clinical pathways are to improve quality of care, to reduce costs, and to decrease inappropriate variation in health care use [24, 25]. Our analysis shows, however, that the establishment of extensive pathways for Chinese hospitals has not led to highly compliant care. The proportion of patients receiving fully compliant care ranged from 0 % (for AMI and heart failure) to 39 % (for pneumonia). Average compliance rates across all indicators for patients with a given condition ranged from 61 % for AMI to 89 % for pneumonia.

In our study, we considered a hospital non-compliant for a particular indicator if the information was not available in the medical record. Thus while the lack of compliance for the KPIs we examined could be driven by non-compliant care, it could also be due to a lack of documentation. It is possible that the care patients receive may be more compliant with clinical pathways than our results suggest, and that hospitals could potentially improve their measured performance through better documentation.

It is also possible that our findings are influenced by the timing of the study. The national pathways were issued relatively recently in 2009 and the importance of adhering to pathways may not have been fully valued by hospital managers in 2012. A qualitative study of the use of clinical pathways in Chinese hospitals identified lack of leadership and support for implementing clinical pathways as barriers to compliance [26].

Low rates of compliance with clinical pathways could also reflect physician concerns over the quality of the pathway. The quality of clinical pathways is dependent upon the quality of the underlying evidence, and, for many clinical applications, the evidence base is inadequate. Even in situations with adequate evidence, clinical pathways could adversely affect patient care if the evidence is not translated effectively into the clinical pathways. In addition, simplistic clinical pathways may not accommodate heterogeneity of patients in practice. An alternative explanation for low rates of compliance is that, in some cases, physicians may believe that guideline compliant care is inappropriate for patients.

We note that we evaluated whether care was consistent with national pathways but did not evaluate whether the national pathways were appropriate. Similarly, hospitals were able to customize the national pathways for their local setting, providing another potential explanation for the deviations from the national pathways that we observed [22]. Determining the extent to which the pathways represent appropriate care is important for evaluating the desirability of increasing rates of compliance with national pathways.

Clinical pathways may also be difficult to implement. Physicians may be concerned that using clinical pathways will reduce their autonomy. Other barriers include a lack of incentives to change practice styles, unclear accountability for health outcomes, competing priorities, lack of resources, health funding constraints, regulation and patient factors (clinical contraindications or history of intolerance to a recommended medication, patient refusal), difficulty coordinating across providers and cultural barriers [6, 26–30]. Correspondingly, studies generally document relatively low levels of compliance with clinical pathways although compliance level varies substantially across sites and across measures.

In our study, differences across conditions in the degree of compliance may have been driven by condition complexity. For example, in the case of pneumonia, treatment does not vary much across patients. In the case of AMI, in contrast, not only is treatment urgent, but guideline compliant care varies significantly across patients. Similarly, heart failure is more complex than cesarean section. Consistent with this explanation, we found the highest rates of non-compliance among AMI and heart failure patients, the two most complex conditions we studied.

Comparison of compliance rates with other countries

The compliance rates for process indicators in public general hospitals of Pudong new area were higher than those from studies from other countries in some cases and were similar or lower in others. For example, 92 % of patients with pneumonia in our study received initial antibiotics within 4 h of hospital arrival, compared to 81 % within 8 h in a study in the U.S. [20]. According to our chart review, 91 % of type-2 diabetics received an HbA1c test, but this rate was about 32 % in the hospitals in the eastern province of Saudi Arabia [31].

But, for patients with AMI, only 5 % received thrombolytic therapy within 30 min of admission, 0 % received PCI within 90 min of admission, and 61 % were advised to continue to use β-blocker after discharge, much lower than corresponding rates in U.S. studies (36, 70 and 79 %, respectively) [13]. The proportion of inpatients with heart failure inappropriately not using β-blockers in our study was 48 %, much higher than that in the U.S. (15 %) [27].

The compliance rates for using β-blocker within 24 h, for advising to continue to use aspirin after discharge, and for advising to continue to use ACEI/ARB after discharge for AMI in our study were 67, 80, and 65 %, similar to those in US and French studies (59.5–74 %, 72–87 %, 53–80 %) [13–15, 32, 33].

The compliance rate for appropriate use of oxytocin during cesarean section was quite high (81 %). In contrast, a survey of 306 clinicians on the implementation of a pathway on oxytocin use during cesarean section in England and Wales found that only 40 % of the surveyed clinicians followed the NICE recommendation [34]. While these comparisons should be interpreted with caution since they are based on studies of different time periods and clinical practice changes rapidly, they point to important differences across countries in the extent to which health care organizations provide pathway compliant care.

Limitations

The findings of this study were based on chart review of 5 common conditions in inpatient care of 7 public general hospitals of Pudong new area in Shanghai. As a result, the study results may not represent the experience of other areas or regions of China, although they are likely to reflect medical practice in Shanghai. We emphasize, however, that Pudong New Area includes both urban and rural areas, indicating that our study sample includes economically diverse patients. In general, because the socioeconomic status is higher and more resources are devoted to health care in eastern China than in other areas, the study results are likely to represent an area in China with relatively high quality of care.

Conclusions

Evidence-based clinical pathways may be used to improve quality of care, reduce costs, and decrease inappropriate variation in clinical practice. But our study found that public general hospitals in Shanghai had low compliance with national clinical pathways for 5 common conditions (pneumonia, AMI, heart failure, cesarean section, type-2 diabetes). The results, which provide unique evidence of the state of quality of care in Chinese public hospitals, indicate that opportunities exist to improve quality of care in Chinese public hospitals.

Our study also suggests that Chinese public hospitals could use the clinical pathways established by the NHFPC as a tool to identify areas in which quality could be improved. Our audit study identified certain KPIs for which Chinese hospitals performed well and others for which they did not. This information could be used to help managers in Chinese public hospitals direct quality improvement activities.

Finally, our results suggest that opportunities exist for the NHFPC to create and for hospitals to use clinical pathways more effectively. Our findings indicated that hospitals in Shanghai often do not provide care consistent with clinical pathways. More research is necessary to determine if the pathways are appropriate and, if so, how to encourage hospitals to change processes of care to be consistent with the guidelines.

Abbreviations

- NHFPC:

-

National Health and Family Planning Commission

- AMI:

-

Acute myocardial infarction

- NICE:

-

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- HIS:

-

Hospital information systems

- KPIs:

-

Key process indicators

- PCI:

-

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- STEMI:

-

ST - segment elevation myocardial infarction

- LBBB:

-

Left bundle branch block

- ACEI:

-

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor

- ARB:

-

Angiotensin receptor antagonist

- OGTT:

-

Oral glucose tolerance test

References

Yu BQ, Sun X, Gu JJ, He XY, Zhou P, Liao XB, et al. Analysis on the process quality of single disease and its influence factors in public general hospitals in pudong new area in Shanghai. Chinese Hospital Manag. 2014;34(10):32–5.

Rong Y, Turnbull F, Patel A, Du X, Wu Y, Gao R. Clinical pathways for acute coronary syndromes in China: protocol for a hospital quality improvement initiative. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2010;9:134–9.

NICE. Clinical guidelines. NICE. 2011. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG. accessed 26 Nov 2013.

Rotter T, Kinsman L, James E, Machotta A, Gothe H, Willis J, et al. Clinical pathways: effects on professional practice, patient outcomes, length of stay and hospital costs. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;3:3.

Landry MT, Landry HT, Beare PG, Roe CW. Guidelines for develo** clinical paths in your agency. Home Healthcare Nurse. 2001;19:69–74.

Polanczyk CA, Biolo A, Imhof BV, Furtado M, Alboim C, Santos C, et al. Improvement in clinical outcomes in acute coronary syndromes after the implementation of a critical pathway. Critical Pathways Cardiol. 2003;2:222–30.

Vandvik PO, Brandt L, Alonso-Coello P, Treweek S, Akl EA, Kristiansen A, et al. Creating clinical practice guidelines we can trust, use, and share: a new era is imminent. Chest J. 2013;144:381–9.

Micieli G, Cavallini A, Quaglini S. Guideline compliance improves stroke outcome a preliminary study in 4 districts in the Italian region of Lombardia. Stroke. 2002;33:1341–7.

Li D, Zhu YB, Zhao F, Wan LL, Zhen JS, Liu H. Application of clinical pathway in scheduled caesarean section. J Practobstet Gynecol. 2011;27:4.

Wang Y. Effect of clinical pathway in caesarean operation. Med Innovation China. 2013;10:2.

McCabe C, Kirchner C, Zhang H, Daley J, Fisman DN. Guideline-concordant therapy and reduced mortality and length of stay in adults with community-acquired pneumonia: playing by the rules. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1525–31.

Shorr AF, Bodi M, Rodriguez A, Sole-Violan J, Garnacho-Montero J, Rello J, et al. Impact of antibiotic guideline compliance on duration of mechanical ventilation in critically ill patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2006;130:93–100.

Szekendi MK. American College of Cardiology. American Heart Association. American College of, and a. American Heart, Compliance with acute MI guidelines lowers inpatient mortality. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2003;18:356–9.

Schiele F, Meneveau N, Seronde MF, Caulfield F, Fouche R, Lassabe G, et al. Compliance with guidelines and 1-year mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction: a prospective study. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:873–80.

Eagle KA, Montoye CK, Riba AL, DeFranco AC, Parrish R, Skorcz S, et al. Guideline-based standardized care is associated with substantially lower mortality in medicare patients with acute myocardial infarction: the American College of Cardiology’s Guidelines Applied in Practice (GAP) Projects in Michigan. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1242–8.

Ranjan A, Tarigopula L, Srivastava RK, Obasanjo OO, Obah E. Effectiveness of the clinical pathway in the management of congestive heart failure. South Med J. 2003;96:661–3.

Heidenreich PA, Hernandez AF, Yancy CW, Liang L, Peterson ED, Fonarow GC. Get With The Guidelines program participation, process of care, and outcome for Medicare patients hospitalized with heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:37–43.

Gregson H. Reducing surgical site infection following caesarean section. Nurs Stand. 2011;25:35–40.

McCraw WM, Kelley PW, Righero AM, Latimer R. Improving compliance with diabetes clinical practice guidelines in military medical treatment facilities. Nurs Res. 2010;59 Suppl 1:66–74.

Ziss DR, Stowers A, Feild C. Community-acquired pneumonia: compliance with centers for Medicare and Medicaid services, national guidelines, and factors associated with outcome. South Med J. 2003;96:949–59.

Wasif N, Gray RJ, Bagaria SP, Pockaj BA. Compliance with guidelines in the surgical management of cutaneous melanoma across the USA. Melanoma Res. 2013;23:276–82.

Du X, Gao R, Turnbull F, Wu Y, Rong Y, Lo S, et al. Hospital quality improvement initiative for patients with acute coronary syndromes in china. A cluster randomized, controlled trial. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7:217–26.

Research Institute of Hospital Management (MOH): Network of Clinical Pathways in China. 2010. http://www.ch-cp.org.cn Accessed 8 May 2015.

Kinsman L. Clinical pathway compliance and quality improvement. Nurs Stand. 2004;18:33–5.

Rello J, Lorente C, Bodí M, Diaz E, Ricart M, Kollef MH. Why do physicians not follow evidence-based guidelines for preventing ventilator-associated pneumonia?: a survey based on the opinions of an international panel of intensivists. Chest. 2002;122:656–61.

Ranasinghe I, Rong Y, Du X, Wang Y, Gao R, Patel A, et al. System barriers to the evidence-base care of acute coronary syndrome patients in China: Qualitative analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7:209–16.

Steinman MA, Dimaano L, Peterson CA, Heidenreich PA, Knight SJ, Fung KZ, et al. Reasons for not prescribing guideline-recommended medications to adults with heart failure. Med Care. 2013;51:901.

Garber AM. Evidence-based guidelines as a foundation for performance incentives. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24:174–9.

Davis DA, Taylor-Vaisey A. Translating guidelines into practice. A systematic review of theoretic concepts, practical experience and research evidence in the adoption of clinical practice guidelines. CMAJ. 1997;157:408–16.

Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, Abboud PA, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282:1458–65.

Mokhtar SA, El Mahalli AA, Al-Mulla S, Al-Hussaini R. Study of the relation between quality of inpatient care and early readmission for diabetic patients at a hospital in the Eastern province of Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J. 2012;18:474–9.

Mehta RH, Montoye CK, Faul J, Nagle DJ, Kure J, Raj E, et al. Enhancing quality of care for acute myocardial infarction: shifting the focus of improvement from key indicators to process of care and tool use: the American College of Cardiology Acute Myocardial Infarction Guidelines Applied in Practice Project in Michigan: Flint and Saginaw Expansion. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:2166–73.

Mehta RH, Montoye CK, Gallogly M, Baker P, Blount A, Faul J, et al. Improving quality of care for acute myocardial infarction: the Guidelines Applied in Practice (GAP) initiative. JAMA. 2002;287:1269–76.

Sheehan SR, Wedisinghe L, Macleod M, Murphy DJ. Implementation of guidelines on oxytocin use at caesarean section: a survey of practice in Great Britain and Ireland. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;148:121–4.

Acknowledgements

This research project was funded by Commission of Health and Family Planning of Pudong New Area. Bundorf was funded by Fudan Senior Visiting Scholarship. We gratefully acknowledge the significant contributions of the following members of the research project team: Ming Li, Buqing Yu, **ngbin Liao, **n Sun, Meiyu Cai, Jianwei Shi and Tianyi Du. The authors thank all the colleagues above for their help in gathering information, analyzing data, and sharing their views with us in the research. The authors also acknowledge all the hospitals that provided assistance with data collection in this research project. The data obtained in this study are the property of the principal researcher.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Study design: HXY; ZP; XD; GJJ; data collection: HXY; ZP; GJJ; data analyses: XD; HXY; KB; critical revision of manuscript: XD; KB. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Analyses on compliance rates for 5 conditions. (DOCX 47 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

He, X.Y., Bundorf, M.K., Gu, J.J. et al. Compliance with clinical pathways for inpatient care in Chinese public hospitals. BMC Health Serv Res 15, 459 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-1121-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-1121-8