Abstract

Background

The diagnosis of a life-limiting condition of a child in the perinatal or neonatal period is a threat to parental hopes. Hope is an interactional and multidimensional construct, and in palliative care, it is a determinant of quality of life, survival, acceptance and peaceful death.

Objective

To map scientific evidence on parents’ hope in perinatal and neonatal palliative care contexts.

Method

a sco** review theoretically grounded on Dufault and Martocchio’s Framework, following the Joanna Briggs Institute methodological recommendations. Searches were performed until May 2023 in the MEDLINE, CINAHL and PsycINFO databases. The searches returned 1341 studies.

Results

Eligible papers included 27 studies, most of which were carried out in the United States under a phenomenological or literature review approach. The centrality of women’s perspectives in the context of pregnancy and perinatal palliative care was identified. The parental hope experience is articulated in dealing with the uncertainty of information and diagnosis, an approach to which interaction with health professionals is a determinant and potentially distressful element. Hope was identified as one of the determinants of co** and, consequently, linked to autonomy and parenthood. Cognitive and affiliative dimensions were the hope dimensions that predominated in the results, which corresponded to the parents’ ability to formulate realistic goals and meaningful interpersonal relationships, respectively.

Conclusion

Hope is a force capable of guiding parents along the path of uncertainties experienced through the diagnosis of a condition that compromises their child’s life. Health professionals can manage the family’s hope by establishing sensitive therapeutic relationships that focus on the dimension of hope. The need for advanced research and intervention in parental and family hope are some of the points made in this study.

Protocol registration

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The discovery of a pregnancy is an essential milestone in the parenting process and creates expectations about life, health and the child [1]. When challenged by prematurity, malformations, congenital diseases and even death, expectations are frustrated, and suffering is experienced [1]. Receiving the diagnosis of a child’s life-threatening condition is challenging to cope with and requires professional support aligned with palliative care (PC).

Perinatal and neonatal Palliative Care is a coordinated care strategy that encompasses actions in obstetric and neonatal care, focusing on maximizing quality of life and comfort for fetuses and newborns with conditions considered life-limiting [2]. The PC practice is not aimed at a disease-modifying treatment but, rather, a collaborative support process for the incorporation and management of losses experienced, centered on people, their values and beliefs [2, 3]. Critical elements in the context of perinatal and neonatal PC are shared decision-making, care planning and co** with distress, with attention to its early introduction and maintenance into childhood [2].

The concept of hope in neonatal and perinatal contexts is related to parental expectations and desires for mobilizing energy to achieve babies’ positive outcomes [4]. Regarding attributes, they are an experiential process targeted toward the present and future in your lives [4]. Ho** is not a single act but a complex of many thoughts, feelings and activities that change with time [5].

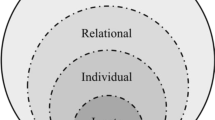

Hope is a multidimensional dynamic life force characterized by confidence yet uncertainty about achieving a future good, which is realistically achievable and personally necessary to the ho** person. In this context, hope has implications for action and interpersonal relatedness, which are directly associated with family co** [6, 7]. In this framework, hope is conceptualized as being compared to two spheres (generalized hope and particularized hope) and six dimensions (affective, cognitive, behavioral, affiliative, temporal, and contextual) [5]. Generalized hope has a broad scope and is not linked to any concrete or abstract hope object. It is the same as intangible hope. Particularized hope involves a special effect or being in a good state – a hope object. Hope objects that are hoped for can be concrete or abstract, explicitly stated, or implied [5].

Each of the six dimensions has a set of components that structure the hope experience. Changes in emphasis within and among the dimensions and their elements characterize the process of ho**. In the same instances, multiple hope processes related to different objects are active in the same person at the same time: (i) the affective dimension of hope focuses on sensations and emotions that permeate the entire ho** process; (ii) the cognitive dimension focuses on the processes by which individuals wish, are imaginative, wonder, perceive, think, remember, learn, generalize, interpret and judge about the identification of hope objects; (iii) the behavioral dimension focuses on the ho** person’s action orientation about hope; and (iv) the affiliative dimension focuses on the ho** person’s sense of relatedness or involvement beyond the self as it bears upon hope. This dimension includes social interactions, mutuality, attachment and intimacy, other-directedness, and self-transcendence; (v) the temporal dimension focuses on the ho** person’s experience of time (past, present, and future) about hopes and ho**. Hope is directed toward a future good, but the past and present are also involved in the ho** process. (vi) The contextual dimension of integrated hope is brought to the forefront of awareness and experience within the context of life as interpreted by the ho** person. The contextual dimension focuses on those life situations or circumstances that surround, influence and are part of a person’s expectations and are an opportunity for the ho** function to be activated or to test hope [5].

Parents of children who have life-limiting and life-threatening diseases undergo profound and pervasive uncertainty, leading to their own illness experience being described as a dual reality in which fighting for survival and recognizing the threat of their child’s death are daily challenges. Hope is an indispensable and vital source of strength for parents, allowing them to cope with their children’s condition and with palliative care and enabling them to continue living. Recognizing the meanings, facets and dimensions of hope that emerge in parents’ experiences may help health professionals better understand and develop a comprehensive, collaborative, and supportive care plan that considers the intricacies inherent to the complexity of the parents’ experience and the importance of hope [6, 7]. This allows for alignment with family-centered care.

The present study sought to integrate knowledge and to advance the understanding of hope within the context of neonatal and perinatal PC, expand health interventions focused on hope, and foster new research in the area. The objective was to map scientific evidence on parental hope in the perinatal and neonatal palliative care contexts.

Methods

This study was developed through the five steps recommended in the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) protocol [8]: definition of the research question; identification of relevant studies; selection and inclusion of studies; data organization; and grou**, synthesis, and reporting of results. To ensure the integrity of this manuscript and methodological rigor, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Sco** Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist and the PRISMA flowchart of the study selection (Fig. 1) were used to report this study [9].

PRISMA flow chart of study selection [7]

A primary survey of the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) and The Cochrane Library was carried out in the second half of 2020, with no previous reviews identified. The research protocol was registered and updated in the Open Science Framework on July 26th, 2023 (https://osf.io/u9xr5/).

The PCC mnemonic was used to elaborate the guiding question: Which is the evidence on the hope of parents who experience perinatal and neonatal palliative care? Population in question (P): parents experiencing fetal and neonatal conditions eligible for palliative care; Concept (C): hope [5]; and Context (C): palliative care.

The research was carried out in the following databases: Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and American Psychological Association (APA PsycINFO) in February 2021, updated in May 2023. Original studies were selected, such as randomized and nonrandomized clinical trials, bibliographic, documentary, experimental, field and case studies, review studies and reflective or theoretical studies, with the following types of approaches: quantitative, qualitative, theoretical, or mixed-methods studies, primary and secondary (reviews/reflective/theoretical) and data triangulation. There was no restriction regarding the research period, and the languages included were English, Spanish, and Portuguese. Exclusion criteria were applied to publications covering other age groups, articles focusing exclusively on death, and those in which the target audience was health professionals and not parents. Letters to the editor, abstracts, clinical protocols, and annals of scientific events were also excluded.

The databases and the language limits were defined based on pretests, and several preliminary searches were carried out with the support and input of a research librarian. These databases were chosen for being the most appropriate for the sco** review on parental hope in perinatal and neonatal palliative care, as they have the most relevant production on this subject matter. Regarding language, we considered the feasibility criterion; however, notably more than 90% of the production on the topic is in English.

The gray literature was an exclusion criterion for this sco** review. As the intersection between the concepts of parental hope and perinatal and neonatal palliative care is a new and emerging process in terms of science, the decision was made to map the literature published on this topic.

This study considers the WHO definition of pediatric palliative care applied to perinatal and neonatal palliative care [10,11,12]. Neonatal-Perinatal Palliative Care is a complete, multidisciplinary approach to providing comprehensive care to families when there is a potentially life-limiting, serious or clinically complex fetal or neonatal diagnosis (from 22 gestational weeks to 28 weeks after birth) to relieve pain and control symptoms and improve the care quality and well-being of fetuses and infants, their families and health care providers involved. It is holistic, family-centered, comprehensive, and multidimensional, so it addresses not only the physical aspect but also the psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions [2, 10, 11].

Concerning eligibility criteria, in this study, the definition of populations in need of perinatal and neonatal palliative care was adopted [2, 10, 11]. The criteria were families or parents facing a condition in which there is a lethal diagnosis in the prenatal or neonatal period or a diagnosis for which there is little or no prospect of long-term survival without severe morbidity or extremely poor quality of life and for which there is no cure [2, 10, 11].

The lists of references of the articles selected were systematically searched to find additional literature relevant to this review.

The search strategy adopted was developed with descriptors and Boolean operators, as well as the MeSH descriptors applied in the scientific databases. (for full search strategies, see Supplementary Table 1).

All the studies retrieved were imported into Rayyan.ai reference management software (https://www.rayyan.ai/), and duplicates were removed. Articles were initially selected by examining their titles and abstracts and, in a second selection stage, based on full-text reading. The selection process was performed based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria prespecified in the review protocol. An independent review was carried out by two pairs of reviewers (AOS, MW, LFF, and PLMD) to reach consensus and increase consistency when selecting the articles that were part of this review. This reference manager software was also used to organize the results.

The process of extracting data from the sources of evidence followed the JBI instrument template for source of evidence details, characteristics, and results extraction. In this study, the following information was extracted: author, year of publication, country where the study was conducted, participants, theoretical and methodological framework, evidence of hope, and implications.

The analytical process took place at the level of characterization of the studies and publication trends and at the level of hope evidence in the parental experience of perinatal and neonatal palliative care. The parental hope evidence was extracted in full and grouped into thematic categories representing the hope dimensions (affective, cognitive, behavioral, affiliative, temporal, and contextual) according to the theoretical model guiding this sco** review [5]. In addition, an analysis of the implications of the studies was conducted to map the gaps and challenges for practice and research into parental and family hope in the context of pediatric and neonatal palliative care.

Studies investigating the perspectives of parents and health professionals were included. The results are presented separately, but only the content referring to the parents’ perspective was considered as the corpus in the process of analyzing and synthesizing the evidence.

The results are summarized in Table 1 with the characterization of the studies, including title, country, publication date, aim, participants and study design. The hope evidence and corresponding dimensions according to Dufault and Martocchio’s Framework [5] are presented in Table 2.

Results

The updated research retrieved 1.341 studies; 64 were excluded due to duplication, and 1,277 had their titles and abstracts read. In turn, 1,229 were excluded, leaving a total of 48 articles: 3 of them were not accessible, and 45 were read in full. Of these articles, 18 were excluded for not meeting the established inclusion criteria (17 did not focus on the parental hope experience, and 1 was a brief book review), leaving the final 27 articles (Fig. 1), identified with the letter ‘S’ in the study reference and an Arabic number, for example: ‘S1’ for Study 1 (Table 1).

Regarding year of publication, country and method, this review found that there are mainly articles published in the last five years (n = 13), carried out in the United States of America – USA (n = 15), and structured as phenomenological reviews (n = 7) and literature reviews (n = 7) (Table 1).

The map** showed that the scientific production on the subject matter of parental hope in perinatal and neonatal palliative care is recent, covering 18 years, with the first study published in 2005 and a more significant production trend from 2011 onwards, maintaining certain homogeneity and consistency from 2018 onwards, indicating an incipient and emerging knowledge area.

The characteristics of the participants included in the studies revealed centrality of women’s perspectives in the context of pregnancy and perinatal palliative care.

The hope dimensions proposed by Dufault and Martochio [5] were identified in the studies under review. The ones that had the greatest expression were Cognitive, Affiliative, Affective and Temporal (Table 2)

Discussion

Faced with the diagnosis and initial information about the child’s situation, the parents’ hope process has been linked to the management of “uncertainties” and the revelations of “certainties”, when information support is crucial and linked to parent-professional interactions [25,26,27,28,29, 13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36, 21,22,23,24]. Parents need collaborative discussions with specialist providers to make decisions about the continuity of the pregnancy and childcare [23, 27, 28]. Trust must be nurtured in care relations because it influences hope and decision-making [23]. In sum, information support exerts effects mainly in the affiliative and cognitive hope dimensions. In this way, parents can identify goals they want to achieve in the short and medium term, as they have the necessary and realistic information to support their experiential processes.

In most cases, in the peri/neonatal PC context, the diagnosis is made by an ultrasonographer who is not part of the family’s care and, therefore, has no knowledge of the family’s life history on first contact. When communication is carried out in a hostile manner and in an unwelcoming environment and ambience, it becomes devastating for hope [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28], again highlighting the cognitive and affiliative hope dimensions.

The articles included in this scope point to the need for parents to process the information they receive to gradually establish attachment and bonds, value time with their newborn, create memories and experience parenthood [12, 29, 30, 27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38, 15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28], which is strongly connected to the affiliative, affective, and temporal hope dimensions. However, there is interference in the cognitive and behavioral dimensions, as it is under the understanding that time with the child is limited and uncertain (temporal and affiliative dimensions) that the parents expressed the desire to make the most of the pregnancy moments, such as naming the child, which lends value to the newborn’s humanity; including it in family rituals (having a Baby Shower), celebrations and holidays; seeking closer physical, auditory and visual interactions with it before and after birth; setting up the baby’s room and buying layette items; going on walks and trips for the newborn to visit different places; and experiencing and performing activities such as other pregnant women (behavioral dimension). These are attachment and care actions with the child [37, 27, 18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36] (affiliative dimension).

Social support takes part in feelings of hope, well-being and resilience and is singular in terms of who they want to connect to [12, 15, 28, 31]. On the other hand, religion and spirituality were highlighted in the articles as important to make sense of the situation and distress faced [13, 32, 33, 31, 24]. Spiritual and religious beliefs contribute to understanding life events and are related to the affiliative dimension of hope. Through religion and spirituality, people seek to mitigate the agony of the finitude of life and their suffering. For parents who have decided to invest in their child’s life, hope is sustained by the belief that life is important; therefore, the child deserves a chance to live [25,26,27,28,29, 13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30, 32, 27,28,29,30,31, 19, 15], as well as by the understanding that having time with the newborn is an opportunity for parenthood [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31, 19, 15, 34]. Higher power and spiritual beliefs guided hope in some studies [24, 31, 32]. The above illustrates that the affective and affiliative hope dimensions have a close connection.

The quality and nature of the relationships involved in parental care shape the parents’ needs, promote a positive experience and a parental role, deal with emotions and resilience [12, 20, 23, 35], and have their wishes respected [35]. This articulation illustrates the relation between the affiliative, affective and cognitive hope dimensions.

The interaction with the professionals at the time of the diagnosis or suspicion was highlighted in the review, attributed as a distressing and unwelcoming moment related to hopelessness. The parenting process is taking place; mothers and fathers are facing a complex and difficult time, in which hope is an imperative of parental existence [39]. Information about the diagnosis or its suspicion interferes with the newborn’s existence in family life (cognitive dimension); therefore, the way in which professionals inform and support bereavement is crucial.

The expansion of prenatal screening and technological advances tends to amplify such situations and, therefore, the establishment of interactions directed to the parents’ needs, focusing efforts on the people affected by the news, respecting silences, providing opportunities for conversations, and placing them at the center of the care provided.

This review identified health professionals’ actions as a direct determinant of parents’ hopes and, therefore, of their co** and the scope of care and its alignment with PC precepts. However, a tendency has been described for professionals to quickly diagnose perinatal conditions that determine the need for PC, without talking to parents about the meaning of such diagnosis and its consequences, let alone sharing decisions with them [40]. The professionals’ effective communication skills and preparedness to work in PC cases are extremely important and linked to the parents’ hope and quality of their experience in PC [40]. However, professionals are currently unprepared to deal with the vulnerabilities, demands and needs that emerge in the PC context [41,42,43], which is seen in the results of this review. It would be a contribution if health professionals’ training turned its gaze to human subjectivity and incorporated this discussion, expanding a human and singular view of care.

This sco** review has produced a broad map** and innovative synthesis of evidence of parental hope in perinatal and neonatal palliative care. The limitations of this study are the languages (English, Portuguese, and Spanish) selected and the noninclusion of gray literature.

Implications of the findings for practice

The consideration of hope is a challenge for professionals in the context of caring for parents under perinatal and neonatal PC. Recognizing manifestations of hope-hopelessness creates, invests, and maintains a context that supports emotional, collaborative, and therapeutic relationships.

Adopting a shared care practice with availability to informative translation, concerning the parents’ time processing to make their decisions, as well as timely and impact communication and sharing decision-making, can enable control and support families to accept the reality of their situation while maintaining a sense of hope in its broadest sense.

Collaboratively establishing a birth plan supports the parental hope experience, especially in determining hope objects. The development of perinatal and neonatal palliative care programs should be structured in the framework of family-centered care in the hope experience.

Adopting evidence of hope in perinatal and neonatal palliative care centered on parents and families is a way of transforming clinical practice with a focus on reaffirming life and creating positive memories and experiences, which is directly related to parental and family empowerment and resilience.

Implications of the findings for research

This review reveals gaps and points to the need for studies that explore fathers’ hope experience and the relationship with decision-making as parents. The same is true at the family level. It is important to consider the diversity of types of families and parenthood, such as homosexual couples and parents, which were only addressed in one of the studies included in this review.

It is possible to gain a greater understanding of the relationship between parental autonomy and hope. The temporal, behavioral and contextual hope dimensions in the parents’ experience are insufficiently explored and comprehended in the perinatal and neonatal PC context.

Qualitative studies are needed to gain a deeper understanding of how the process of “ho**” takes place in this population during the perinatal and neonatal periods. Once this phenomenon is better understood, studies could be carried out using mixed research methodologies, which would allow the “promoting hope” intervention to be evaluated in terms of health gains for this population.

Conclusions

This review asserted hope as an important co** mechanism for parents in the context of perinatal and neonatal PC. When there was a prevalence of uncertainties, hope supported the belief in a potentially different outcome from the one predicted by the professionals, and in the face of confirmations, it turned to the exercise and expression of parenting through the intentional creation of bonds, care actions and memories. Hope is a constant in the experience of parents living with the diagnosis of a fetal condition compromising the child’s life. It contributes to the research on movement and rebalancing, acting as a driving force and with a tendency to push parents from inertia.

Hope is the strength that guides parents in facing uncertainties through the diagnosis of a condition that compromises their child’s life. Interactions with health professionals exert a direct impact on hope and, consequently, on family behaviors and responses. Parents believe that health professionals can manage the family’s hope by establishing “sensitive” therapeutic relationships that focus on the therapeutic dimension of hope: assertive communication, transmitting clear, realistic, and respectful information. Hope positions parents on a co** line consonant with their beliefs and reality. This experience contributes to comfort, trust in professionals and confidence in decision-making, serving as a guide and autonomy booster. The relational contexts (especially with professionals) in palliative care suggest inadequacies in promoting the parents’ hope experience.

Accessing and recognizing hope dynamics is a premise for health care aimed at quality of life, comfort, and autonomy for parents in perinatal and neonatal PC, and therefore, it is a professional commitment.

Diverse evidence of parental hope has been mapped in this review in light of its dimensions, with contributions to assessing and identifying hope objects, resources and threats.

Data Availability

All data and materials analyzed during this study are included in this manuscript.

References

Bolibio R, Jesus RC, de Oliveira A, de Gibelli FF, Benute MABC, Gomes GRG, Nascimento AL, Barbosa NBO, Zugaib TVA, Francisco M, Bernardes RPV. LS. Pallitative care in fetal medicine. Rev. Med. (São Paulo). 1998, Jul; 97(2):208 – 15. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.1679-9836.v97i2p208-215

Quinn M, Weiss AB, Crist JD. Early for everyone: reconceptualizing Palliative Care in the neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Adv Neonatal Care. 2020;20(2):109–17. https://doi.org/10.1097/ANC.0000000000000707. PMID: 31990696.

Hammond J, Wool C, Parravicini E. Assessment of Healthcare professionals’ self-perceived competence in Perinatal/Neonatal Palliative Care after a 3-Day training course. Front Pediatr [Internet]. 2020;8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2020.571335

Guedes A, Carvalho MS, Laranjeira C, Querido A, Charepe Z. Hope in palliative care nursing: concept analysis. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2021;27(4):176–87. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijpn.2021.27.4.176. PMID: 34169743.

Dufault K, Martocchio BC, Hope. Its spheres and dimensions. Nurs Clin North Am. 1985;20(2):379–91.

Szabat M. Parental experience of hope in pediatric palliative care: critical reflections on an exemplar of parents of a child with trisomy 18. Nurs Inq. 2020;27:e1234. https://doi.org/10.1111/nin.12341

Bally JMG, Smith NR, Holtslander L, et al. A metasynthesis: uncovering what is known about the experiences of families with children who have life-limiting and life-threatening illnesses. J Pediatr Nurs. 2018;38:88–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2017.11.004

Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco AC, Khalil H. Chapter 11: Sco** Reviews (2020 version). In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JB Manual for Evidence Synthesis, JBI, 2020. Available from https://synthesismanual.jbi.global. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-12

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

WHO. Integrating palliative care and symptom relief into pediatrics: a WHO guide for health care planners, implementers and managers. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

Dombrecht L, Chambaere K, Beernaert K, Roets E, De Vilder De Keyser M, De Smet G, et al. Compon Perinat Palliat Care: Integr Rev Child. 2023;10:482. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030482

Tatterton MJ, Fisher MJ. You have a little human being kicking inside you and an unbearable pain of knowing there will be a void at the end’: A meta-ethnography exploring the experience of parents whose baby is diagnosed antenatally with a life limiting or life-threatening condition [published online ahead of print, 2023 May 2]. Palliat Med. 2023;2692163231172244. https://doi.org/10.1177/02692163231172244

Humphrey LM, Schlegel AB. Longitudinal perinatal palliative care for severe fetal neurologic diagnoses. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2022;42:100965. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spen.2022.100965

O’Connell O, Meaney S, O’Donoghue K. Anencephaly; the maternal experience of continuing with the pregnancy. Incompatible with life but not with love. Midwifery. 2019;71:12–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2018.12.016

Chapman B. A case of Anencephaly: Integrated Palliative Care. New Z Coll Midwives J. 2013;1(48). https://doi.org/10.12784/nzcomjnl48.2013.1.5-8

Roscigno CI, Savage TA, Kavanaugh K, Moro TT, Kilpatrick SJ, Strassner HT, Grobman WA, Kimura RE. Divergent views of hope influencing communications between parents and hospital providers. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(9):1232–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312449210

Moro T, Kavanaugh K, Savage TA, Reyes MR, Kimura RE, Bhat R. Parent decision making for life support for extremely premature infants. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2011;25(1):52–60. https://doi.org/10.1097/JPN.0b013e31820377e5

Hasegawa SL, Fry JT. Moving toward a shared process: the impact of parent experiences on perinatal palliative care. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41(2):95–100. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semperi.2016.11.002

Côté-Arsenault D, Denney-Koelsch E. Have no regrets: parents’ experiences and developmental tasks in pregnancy with a lethal fetal diagnosis. Soc Sci Med. 2016;154:100–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.02.033

Kavanaugh K, Hershberger P. Perinatal loss in low-income African American parents. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2005;34(5):595–605. https://doi.org/10.1177/0884217505280000

Janvier A, Farlow B, Barrington KJ. Parental hopes, interventions, and survival of neonates with trisomy 13 and trisomy 18. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2016;172(3):279–87. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.c.31526

Janvier A, Lantos J, Aschner J, Barrington K, Batton B, Batton D, et al. Stronger and more vulnerable: a balanced view of the impacts of the NICU experience on parents. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3):e20160655. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-0655

Rosenthal SA, Nolan MT. A meta-ethnography and theory of parental ethical decision making in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2013;42(4):492–502. https://doi.org/10.1111/1552-6909.12222

Rosenbaum JL, Smith JR, Zollfrank R. Neonatal end-of-life spiritual support care. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2011;25(1):61–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/JPN.0b013e318209e1d2

Berken DJ, van Dam H. How we handled our son’s birth at the limits of viability after an unexpected pregnancy. Acta Paediatr. 2023;112(5):931–3. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.16692. Epub 2023 Feb 21. PMID: 36734149.

Alvarenga WA, de Montigny F, Zeghiche S, Polita NB, Verdon C, Nascimento LC. Understanding the spirituality of parents following stillbirth: a qualitative meta-synthesis. Death Stud. 2021;45(6):420–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2019.1648336

Weeks A, Saya S, Hodgson J. Continuing a pregnancy after diagnosis of a lethal fetal abnormality: views and perspectives of Australian health professionals and parents. Australian and New Zealand J of Obstet and Gynecol. 2020;60(5):746–52.

Black BP. Truth telling and severe fetal diagnosis. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2011;25(1):13–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/JPN.0b013e318201edff

Jackson P, Power-Walsh S, Dennehy R, O’Donoghue K. Fatal fetal anomaly: experiences of women and their partners. Prenat Diagn. 2023;43(4):553–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.6311. Epub 2023 Jan 29. PMID: 36639719.

Crawford A, Hopkin A, Rindler M, Johnson E, Clark L, Rothwell E. Women’s experiences with Palliative Care during pregnancy. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2021;50(4):402–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogn.2021.02.009

Cortezzo DE, Ellis K, Schlegel A. Perinatal Palliative Care Birth Planning as Advance Care Planning. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:556. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2020.00556

Kain VJ. Perinatal Palliative Care: Cultural, spiritual, and Religious considerations for Parents-what clinicians need to know. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:597519. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2021.597519

Marc-Aurele KL. Decisions parents make when Faced with potentially life-limiting fetal diagnoses and the importance of Perinatal Palliative Care. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:574556. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2020.574556

Côté-Arsenault D, Denney-Koelsch E. My baby is a person: parents’ experiences with Life-threatening fetal diagnosis. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(12):1302–8. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2011.0165

Cortezzo DE, Bowers K, Cameron Meyer M. Birth Planning in Uncertain or Life-limiting fetal diagnoses: perspectives of Physicians and Parents. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(11):1337–45. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2018.0596

Meaney S, Corcoran P, O’Donoghue K. Death of one twin during the Perinatal period: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(3):290–3. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2016.0264

Hein K, Flaig F, Schramm A, Borasio GD, Führer M. The path is made by walking-map** the Healthcare Pathways of Parents Continuing Pregnancy after a severe life-limiting fetal diagnosis: a qualitative interview study. Child (Basel). 2022;9(10):1555. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9101555

Denney-Koelsch EM, Côté-Arsenault D, Jenkins Hall W. Feeling cared for Versus Experiencing added Burden: parents’ interactions with health-care providers in pregnancy with a Lethal fetal diagnosis. Illn Crisis Loss. 2016;26(4):293–315. https://doi.org/10.1177/1054137316665817

Magão MTG. Hope in action: The experience of hope in parents of children with a chronic disease. Thesis (Doctorate) - University of Lisbon [Internet] [S.l.], 2017. Available at: https://repositorio.ul.pt/bitstream/10451/40069/1/ulsd731061_td_Maria_Magao.pdf

Flaig F, Lotz JD, Knochel K, Borasio GD, Führer M, Hein K. Perinatal Palliative Care: a qualitative study evaluating the perspectives of pregnancy counselors. Palliat Med. 2019;33(6):704–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216319834225

Marc-Aurele KL, English NK. Primary palliative care in neonatal intensive care. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41(2):133–9. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semperi.2016.11.005

Antunes M, Viana CR, Charepe Z. Hope aspects of the women’s experience after confirmation of a high-risk pregnancy Condition: a systematic sco** review. Healthcare. 2022;10(12):2477. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10122477

Lord S, Williams R, Pollard L, Ives-Baine L, Wilson C, Goodman K, et al. Reimagining Perinatal Palliative Care: a broader role for support in the Face of uncertainty. J Palliat Care. 2022;37(4):476–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/08258597221098496

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the research librarian at the University of São Carlos for her support and input in structuring the search strategies.

Funding

This study was partially financed by National Funds through FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., under the project UIDP/ 04279/2020 and was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brazil - (CAPES) - finance code 001. The funding bodies played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, interpretation of data, and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Contributions to conception and writing: AOS, MW, LFF, PLMD, ZCDrafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content: AOS, MW, ZC.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that might appear to influence the work reported in this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Silveira, A.O., Wernet, M., Franco, L.F. et al. Parents’ hope in perinatal and neonatal palliative care: a sco** review. BMC Palliat Care 22, 202 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-023-01324-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-023-01324-z