Abstract

Background

Depressive disorders have been identified as a significant contributor to non-fatal health loss in China. Among the various subtypes of depressive disorders, dysthymia is gaining attention due to its similarity in clinical severity and disability to major depressive disorders (MDD). However, national epidemiological data on the burden of disease and risk factors of MDD and dysthymia in China are scarce.

Methods

This study aimed to evaluate and compare the incidence, prevalence, and disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) caused by MDD and dysthymia in China between 1990 and 2019. The temporal trends of the depressive disorder burden were evaluated using the average annual percentage change. The comparative risk assessment framework was used to estimate the proportion of DALYs attributed to risk factors, and a Bayesian age-period-cohort model was applied to project the burden of depressive disorders.

Results

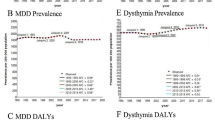

From 1990 to 2019, the overall age-standardized estimates of dysthymia in China remained stable, while MDD showed a decreasing trend. Since 2006, the raw prevalence of dysthymia exceeded that of MDD for the first time, and increased alternately with MDD in recent years. Moreover, while the prevalence and burden of MDD decreased in younger age groups, it increased in the aged population. In contrast, the prevalence and burden of dysthymia remained stable across different ages. In females, 11.34% of the DALYs attributable to depressive disorders in 2019 in China were caused by intimate partner violence, which has increasingly become prominent among older women. From 2020 to 2030, the age-standardized incidence, prevalence, and DALYs of dysthymia in China are projected to remain stable, while MDD is expected to continue declining.

Conclusions

To reduce the burden of depressive disorders in China, more attention and targeted strategies are needed for dysthymia. It’s also urgent to control potential risk factors like intimate partner violence and develop intervention strategies for older women. These efforts are crucial for improving mental health outcomes in China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

China, with 18% of the world’s population, has undergone significant economic and institutional changes over the past three decades. As such, it serves as an excellent research sample for other develo** countries and the world as a whole. Despite its rapid economic development, China faces social issues like increasing competitive pressure, rising medical costs, widening poverty gaps, and increasing psychological stress, which have contributed to a rise in the incidence of depression over time [1, 2]. This trend has posed a serious threat to society and personal lives [3], necessitating the urgent need to understand the epidemic trend of depressive disorders and develop effective strategies to address them.

While major depressive disorder (MDD) is often the focus of attention due to its severity and short-term effects, another subtype of depression, dysthymia, is frequently overlooked [4, 5]. Dysthymia, defined by the ICD-10 as a persistent depressive mood lasting for more than two years and with lower severity than MDD, is associated with significantly impaired quality of life, despite its milder symptoms [6]. For instance, individuals with dysthymia exhibit lower rates of full-time employment and are more likely to depend on public assistance compared to the general population and individuals with MDD [7]. Moreover, dysthymia is characterized by higher prevalence in the general population, greater childhood adversity, more functional impairment, and a higher risk for suicide attempts [8]. Compared to the episodic form of MDD, dysthymia is associated with more severe life damage and higher social and economic costs [9]. Thus, analyzing the differences between MDD and dysthymia may yield more disease phenotypes for exploratory research on etiology and treatment [8]. However, comparative research data on MDD and dysthymia remain scarce [8].

Currently, the pathogenesis of depression remains unclear and its high recurrence rate continues to pose a significant treatment burden. Ren et al. reported that the prevalence and DALY rate of depression had increased to varying degrees across all age groups in China from 1990 to 2017 [2]. However, their study only analyzed the prevalence and DALYs of depression by age, gender, and province. Yueqin Huang et al. conducted a cross-sectional epidemiological survey of the prevalence of adult depression in 157 nationwide representative population-based disease surveillance points in 31 provinces in China [2]. The results showed a lifetime weighted prevalence of 3.4% for MDD and 1.4% for dysthymia. However, dysthymia is considered to be equally disabling and clinically severe as MDD. Therefore, the identification, prevention, and treatment of dysthymia should be considered as important as that of MDD. Alarmingly, only 9.5% of the 1007 participants with depressive disorders used mental health services and only 0.5% of those with depressive disorders received adequate treatment. Therefore, detailed epidemiological characteristics of MDD and dysthymia, especially risk factors, are important to improve treatment engagement and reduce the burden of disease [10].

However, few studies have thoroughly assessed, compared, and projected the burden of MDD and dysthymia, along with their risk factors, in China. Such studies could greatly assist in the formulation of policies for preventing and managing depressive disorders. For example, the significant increase in disability-adjusted life years(DALYs) of MDD attributable to bullying victimization over the last three decades requires extra attention [11]. Additionally, a possible causal relationship between bullying victimization and depressive disorders has been suggested [12]. Bullying victimization not only increases the risk of mental disorders but also carries significant direct costs for individuals and society as a whole [13]. Unfortunately, the burden of disease resulting from bullying victimization was not assessed until the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2017.

The aim of this study is to evaluate and compare the burden of MDD and dysthymia in China from 1990 to 2019, including temporal trends by age, sex, disease subtypes, and risk factors. Furthermore, this study seeks to project the burden of dysthymia and MDD separately from 2020 to 2030. This research can aid in the evaluation of current prevention strategies and provide additional theoretical support for their revision.

Methods

Depression definition and data sources

All data and analyses presented in this study were based on the GBD Study 2019, which provides estimates of incidence, prevalence, deaths, and DALYs in different countries and regions from 1990 to 2019. The GBD Study employs meticulous methods that have been described in detail in earlier publications [14, 15]. Using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual IV (DSM-4) and the International Classification of Diseases 10th revision (ICD-10), the GBD Study examined two major categories of depression: MDD and dysthymia. The codes used to identify depressive disorders were DSM-IV-TR: 296.21-24, 296.31-34, 300.4 and ICD-10: F32.0-9, F33.0-9, F34.1, which covered MDD and dysthymia and excluded cases due to general medical conditions or substance use. To estimate the prevalence, incidence, duration, and excess fatality associated with depressive disorders, the GBD Study conducted a comprehensive search of PsycInfo, Embase, PubMed, the grey literature, and consulted with experts. A total of 517 and 107 original data sources were collected for MDD and dysthymia, respectively, to enable global assessment of depressive disorders. Detailed information on the search strategies, methodologies, and estimation of depression can be found on the GBD Study website (http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-2019).

To analyze the burden of depressive disorders in China, we utilized the GBD database and selected China as the location, “depressive disorder” as the cause, and “incidence,” “prevalence,” and “DALYs” as measures. The DALYs were computed by adding disability-adjusted life years (YLDs) and YLLs years of life lost (YLLs) in GBD study. Because depressive disorders are nonfatal disease, the DALYs due to depressive disorders are equivalent to the YLDs, which were computed by sequela as prevalence multiplied by the disability weights (DW) for the health state associated with that sequela [14]. In calculating the 95% uncertainty intervals (UIs), we utilized the 25th and 975th ordered percentiles of 1,000 random draws in the GBD study. Age-standardized rates for the incidence, prevalence, and DALYs of depressive disorders were calculated using the World Health Organization (WHO) World Standard Population Distribution (2000–2025). Additionally, the United Nations World Population Prospects 2019 Revision was used to predict the population.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The authors confirm that this study was conducted in compliance with the ethical standards set by national and institutional committees on human experimentation, as well as the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 (revised in 2008). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Qilu Hospital of Shandong University (approval number KYLL-202,011(KS)-239). As the GBD 2019 study is a public database with all data being anonymous, no further ethical approval was required for this study.

Data analysis

This study aimed to describe the shift in incidence, prevalence, and DALYs of depressive disorders in China from 1990 to 2019, with all cases divided into 5-year age groups. The average annual percentage change (AAPC) was calculated to quantify temporal trends of incidence, prevalence, and DALYs [16,17,18]. The regression line was fitted to the natural logarithm of the rates, i.e., y = α + βx + ɛ, where y = ln (rate) and x = calendar year, and the AAPC was calculated as 100 × (exp(β)-1). A 95% confidence interval (CI) of AAPC was also computed. To estimate the proportion of DALYs attributed to potential risk factors, the comparative risk assessment (CRA) framework and three well-established risk factors for depressive disorders (bullying victimization, child sexual violence, and intimate partner violence) estimated in the GBD 2019 study were applied in the present study [15]. According to the World Cancer Research Fund grades of convincing or probable evidence, intimate partner violence, bullying victimization and childhood sexual abuse were identified as attributable risk factors of MDD. The disease burden attributable to risk factors was estimated the following six key steps: inclusion of risk–outcome pairs in the analysis; estimation of relative risk as a function of exposure; estimation of exposure levels and distributions; determination of the counterfactual level of exposure, the level of exposure with minimum risk called the theoretical minimum risk exposure level (TMREL); computation of population attributable fractions and attributable burden; and estimation of mediation of different risk factors through other risk factors [19]. Bayesian age-period-cohort analysis with integrated nested Laplace approximation was used to project the numbers of cases, prevalence, and DALYs for depressive disorders by disease subtypes from 2020 to 2030. This method has been proven to have better accuracy in forecasting non-communicable diseases, especially in non-longer projection years, compared with other models [36]. The socio-cultural environment in China can lead to the elderly perceiving themselves as a burden to their families and society, which may gradually lead to depression [37]. Furthermore, there is often a long-term depression around retirement age, and compared to retiring or being inactive, working in the long-term is associated with lower depressive symptoms [38]. With the impact of the “one-child policy” and the rapid aging of the population, the burden of disease is expected to increase in the future.

The results of present study showed that intimate partner violence was the most significant contributor to the burden of depression in China, followed by bullying victimization and child sexual violence. In recent years, the level of intimate partner violence has gradually increased in China, which can lead to victims’ feelings of fear, helplessness, powerlessness, and isolation [39]. Meta-analyses have indicated that the prevalence of depression is high among women who have experienced psychological violence (65.8%), physical violence (69.5%), and sexual violence (75.8%) [40]. The study also confirmed that the tendency of young women to suffer from intimate partner violence has decreased in the past decades but has increased in recent years. In China, the DALYs rate per 10,000 elderly women suffering from intimate partner violence has unexpectedly increased in recent years. This could be due to the social status of women and increasing economic stress, which predisposes them to anger, frustration, and manifestations of violence [41, 42]. These economic pressures, and the resulting changes in perception, ultimately lead to a higher risk of intimate partner violence. Furthermore, bullying victimization, which commonly occurs among school-aged children, is a salient stressor that leads to deficits in emotion regulation across the lifespan [43]. There is strong evidence that bullying victimization is associated with suicidal ideation and attempts and that depression is a major undesirable outcome. Depression was found to be a moderator between bullying and suicidality [44,45,46]. In addition, the estimated prevalence of child sexual violence among males and females in China was 9.1% and 8.9%, respectively. The prevalence of male child sexual violence in China is higher than the global prevalence (7.9%) [47, 48]. Childhood sexual violence has negative effects on victims’ physical and mental health and is associated with an increased risk of depression [49]. Although the risk of child sexual violence has remained stable from 1990 to 2019, the problem still needs to be taken seriously. Early intervention to identify and support victims of life trauma could prevent the development of nasty conditions.

According to the WHO, depressive disorders are one of the leading causes of disability worldwide and contribute to the global burden of disease, accounting for about 46.9 million DALYs in 2019 [14]. However, in China, ASIR, ASPR, and ASDR are lower than in numerous developed countries. It is possible that this data is underestimated due to stigma and/or lack of mental health knowledge. Only 9.5% of people with depressive disorders used mental health services [10], much lower than in the United States (57.3% for MDD) [50] and other high-income countries [51], which confirms this speculation. Moreover, the uneven distribution of healthcare resources in China, especially the shortage of mental health services and inadequate training of mental health workers in western rural areas, has led to low diagnosis rates of depressive disorders [52]. Patients with depression often prefer to visit local tertiary or secondary general hospitals first, rather than a psychiatric specialist. Additionally, the Chinese are more likely to seek help from physicians in traditional Chinese medicine, resulting in some depressed patients being diagnosed with “mental disorders” instead of depressive disorders [10]. Furthermore, among depressed patients who first seek treatment in psychiatric hospitals, the number of those who worsen due to poor treatment or excessive medical expenses is staggering, leading to a waste of medical resources [53]. Therefore, the media, schools, and communities should strengthen mental health education and popularize relevant knowledge for the public in China. Moreover, psychological consulting and therapy should be a conventional procedure added to the therapy process of depressive disorders. Especially since the aging population is growing fast, the higher incidence rates of depression among the elderly remind us of the need to pay special attention to this group. It is meaningful to create a friendly social environment for the elderly and establish a positive attitude towards aging in the whole society [54]. Therefore, it is essential that the allocation of medical resources in China be based on the demographic characteristics of the disease burden.

Limitations

While this study sheds light on the burden of depression in China, there are some limitations to consider. Firstly, the estimates provided in GBD 2019 are based on mathematical modeling, and further research is needed to reflect a more realistic burden of disease. Secondly, depression in China carries a significant social stigma that can lead to underdiagnosis and may skew the estimated burden of depression in the country. Thirdly, this study only analyzed the national disease burden of depression and did not investigate the prevalence, incidence, DALYs, and risk factors of depression in different provincial or economic regions of China. Future research should focus on addressing these limitations to provide a more comprehensive picture of depression in China.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is evident that the burden of depressive disorders in China has been increasing over the past 30 years due to various factors such as a large population, aging, economic pressures, and poor treatment, and it is expected to continue increasing in the future. Dysthymia, which was previously overlooked, is now receiving more attention due to its similar disability and clinical severity as MDD, and the detection rate of dysthymia is gradually increasing, leading to a shift in the subtypes of depressive disorders. MDD has seen a decrease in all age-standardized indicators, and the peak population of patients tends to be older, while dysthymia has remained relatively stable. It is crucial to establish targeted prevention and treatment strategies based on the existing population structure and risk factors. These strategies should focus on early identification and treatment of dysthymia, mental health education, attention to population aging, and early intervention for individuals suffering from life trauma. By implementing these multiple strategies, the burden of depressive disorders can be reduced in China.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the online database (http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool)

References

Li W, Liu E, Balezentis T, ** H, Streimikiene D. Association between socioeconomic welfare and depression among older adults: evidence from the China health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. Soc Sci Med. 2021;275:113814.

Ren X, Yu S, Dong W, Yin P, Xu X, Zhou M. Burden of depression in China, 1990–2017: findings from the global burden of disease study 2017. J Affect Disord. 2020;268:95–101.

National Institute of Mental Health. Depression [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2021 Jun 14]. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/depression/.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). 2013.

Tyrer P, Tyrer H, Johnson T, Yang M. Thirty-year outcome of anxiety and depressive disorders and personality status: comprehensive evaluation of mixed symptoms and the general neurotic syndrome in the follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2021;1:10.

Carta MG, Paribello P, Nardi AE, Preti A. Current pharmacotherapeutic approaches for dysthymic disorder and persistent depressive disorder. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2019;20(14):1743–54.

Hellerstein DJ, Agosti V, Bosi M, Black SR. Impairment in psychosocial functioning associated with dysthymic disorder in the NESARC study. J Affect Disord. 2010;127(1):84–8.

Schramm E, Klein DN, Elsaesser M, Furukawa TA, Domschke K. Review of dysthymia and persistent depressive disorder: history, correlates, and clinical implications. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(9):801–12.

Nübel J, Guhn A, Müllender S, Le HD, Cohrdes C, Köhler S. Persistent depressive disorder across the adult lifespan: results from clinical and population-based surveys in Germany. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):58.

Lu J, Xu X, Huang Y, Li T, Ma C, Xu G, et al. Prevalence of depressive disorders and treatment in China: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(11):981–90.

Hong C, Liu Z, Gao L, ** Y, Shi J, Liang R, et al. Global trends and regional differences in the burden of anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder attributed to bullying victimisation in 204 countries and territories, 1999–2019: an analysis of the global burden of Disease Study. Epidemiol Psychiatric Sci. 2022 ed;31:e85.

Jadambaa A, Thomas HJ, Scott JG, Graves N, Brain D, Pacella R. The contribution of bullying victimisation to the burden of anxiety and depressive disorders in Australia. Epidemiol Psychiatric Sci. 2020 ed;29.

Wolke D, Lereya ST. Long-term effects of bullying. Arch Dis Child. 2015;100(9):879–85.

GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1204–22.

GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1223–49.

Yang X, Fang Y, Chen H, Zhang T, Yin X, Man J et al. Global, regional and national burden of anxiety disorders from 1990 to 2019: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences. 2021 ed;30.

Yu J, Yang X, He W, Ye W. Burden of pancreatic cancer along with attributable risk factors in Europe between 1990 and 2019, and projections until 2039. Int J Cancer. 2021;ijc.33617.

Zhang T, Chen H, Yin X, He Q, Man J, Yang X, et al. Changing trends of disease burden of gastric cancer in China from 1990 to 2019 and its predictions: findings from global burden of Disease Study. Chin J Cancer Res. 2021;33(1):11–26.

GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(2):137–50.

Du Z, Chen W, **a Q, Shi O, Chen Q. Trends and projections of kidney cancer incidence at the global and national levels, 1990–2030: a bayesian age-period-cohort modeling study. Biomark Res. 2020;8(1):16.

Knoll M, Furkel J, Debus J, Abdollahi A, Karch A, Stock C. An R package for an integrated evaluation of statistical approaches to cancer incidence projection. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2020;20(1):257.

Sang W, Li Y, Su L, Yang F, Wu W, Shang X, et al. A comparison of the clinical characteristics of Chinese patients with recurrent major depressive disorder with and without dysthymia. J Affect Disord. 2011;135(1–3):106–10.

Gureje O. Dysthymia in a cross-cultural perspective. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2011;24(1):67–71.

Klein DN, Shankman SA, Rose S. Ten-year prospective follow-up study of the naturalistic course of dysthymic disorder and double depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(5):872–80.

Verduijn J, Verhoeven JE, Milaneschi Y, Schoevers RA, van Hemert AM, Beekman ATF, et al. Reconsidering the prognosis of major depressive disorder across diagnostic boundaries: full recovery is the exception rather than the rule. BMC Med. 2017;15(1):215.

Tu WJ, Zeng X, Liu Q. Aging tsunami coming: the main finding from China’s seventh national population census. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2022;34(5):1159–63.

Li M, Gao W, Zhang Y, Luo Q, **ang Y, Bao K, et al. Secular trends in the incidence of major depressive disorder and dysthymia in China from 1990 to 2019. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):2162.

Klein DN, Black SR. Persistent Depressive Disorder. In: The Oxford Handbook of Mood Disorders [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2022 Feb 11]. (Psychology, Neuropsychology, Clinical Psychology). https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199973965.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199973965-e-20.

Keller MB, Trivedi MH, Thase ME, Shelton RC, Kornstein SG, Nemeroff CB, et al. The Prevention of recurrent episodes of Depression with Venlafaxine for two years (PREVENT) study: outcomes from the 2-year and combined maintenance phases. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(8):1246–56.

Kocsis JH, Gelenberg AJ, Rothbaum B, Klein DN, Trivedi MH, Manber R, et al. Chronic forms of major depression are still undertreated in the 21st century: systematic assessment of 801 patients presenting for treatment. J Affect Disord. 2008;110(1–2):55–61.

Levkovitz Y, Tedeschini E, Papakostas GI. Efficacy of antidepressants for Dysthymia: a Meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(4):5964.

McCullough JP, Kasnetz MD, Braith JA, Carr KF, Cones JH, Fielo J, et al. A longitudinal study of an untreated sample of predominantly late onset characterological dysthymia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1988;176(11):658–67.

Hu Y, Wang J, Nicholas S, Maitland E. The sharing economy in China’s Aging Industry: applications, challenges, and recommendations. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(7):e27758.

Tang X, Qi S, Zhang H, Wang Z. Prevalence of depressive symptoms and its related factors among China’s older adults in 2016. J Affect Disord. 2021;292:95–101.

Wang R, Bishwajit G, Zhou Y, Wu X, Feng D, Tang S, et al. Intensity, frequency, duration, and volume of physical activity and its association with risk of depression in middle- and older-aged Chinese: evidence from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study, 2015. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(8):e0221430.

Zhao D, Hu C, Chen J, Dong B, Ren Q, Yu D, et al. Risk factors of geriatric depression in rural China based on a generalized estimating equation. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018;30(10):1489–97.

Bai X, Lai DWL, Guo A. Ageism and Depression: perceptions of older people as a Burden in China. J Soc Issues. 2016;72(1):26–46.

Madero-Cabib I, Azar A, Guerra J. Simultaneous employment and depressive symptom trajectories around retirement age in Chile. Aging Ment Health. 2021;1:10.

Beydoun HA, Beydoun MA, Kaufman JS, Lo B, Zonderman AB. Intimate partner violence against adult women and its association with major depressive disorder, depressive symptoms and postpartum depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(6):959–75.

Yuan W, Hesketh T. Intimate Partner Violence and Depression in women in China. J Interpers Violence. 2019;0886260519888538.

Norlander B, Eckhardt C. Anger, hostility, and male perpetrators of intimate partner violence: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25(2):119–52.

Yuan W, Hesketh T. Intimate partner violence against women and its association with depression in three regions of China: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2019;394:S5.

Cicchetti D, Toth SL. Child maltreatment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2004;1(1):409–38.

Brunstein klomek A, Marrocco F, Kleinman M, Schonfeld IS, Gould MS. Bullying, Depression, and suicidality in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(1):40–9.

Garnefski N, Kraaij V. Bully victimization and emotional problems in adolescents: moderation by specific cognitive co** strategies? J Adolesc. 2014;37(7):1153–60.

Stapinski LA, Araya R, Heron J, Montgomery AA, Stallard P, Anxiety. Stress Co**. 2015;28(1):105–20.

Ma Y. Prevalence of childhood sexual abuse in China: a Meta-analysis. J Child Sex Abuse. 2018;27(2):107–21.

Pereda N, Guilera G, Forns M, Gómez-Benito J. The prevalence of child sexual abuse in community and student samples: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(4):328–38.

Arreola S, Neilands T, Pollack L, Paul J, Catania J. Childhood sexual experiences and Adult Health Sequelae among Gay and Bisexual men: defining childhood sexual abuse. J Sex Res. 2008;45(3):246–52.

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, ** R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorderresults from the national comorbidity survey replication (NCS-R). JAMA. 2003;289(23):3095–105.

Wang PS, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Borges G, Bromet EJ, et al. Use of mental health services for anxiety, mood, and substance disorders in 17 countries in the WHO world mental health surveys. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):841–50.

Liang D, Mays VM, Hwang WC. Integrated mental health services in China: challenges and planning for the future. Health Policy Plann. 2018;33(1):107–22.

Zhang W, Li X, Lin Y, Zhang X, Qu Z, Wang X, et al. Pathways to psychiatric care in urban north China: a general hospital based study. Int J Mental Health Syst. 2013;7(1):22.

Mitina M, Young S, Zhavoronkov A. Psychological aging, depression, and well-being. Aging. 2020;12(18):18765–77.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the countless individuals who have contributed to the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 in various capacities.

Author contributors

Conceptualization: WW, LJY, XRY; Data curation: XRY, WW; Formal analysis: WW, YHW, FW, HC, XRY, LXY; Funding acquisition: XRY, LJY; Investigation: LJY, LXY; Methodology: LJY, XRY, LXY; Project administration: XRY, LJY; Resources: WW, HC, XQQ, LXY, XRY; Software: XRY, HC; Supervision: LJY, LXY; Validation: WW, XRY, LJY, FW; Visualization: WW, YHW, XQQ, FW; Writing – original draft: WW, YHW, XRY, FW, HC, XQQ; Writing – review & editing: LJY, LXY, XRY.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers: 82103912); the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (grant number: ZR2020QH302); and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant number: 2017YFC0907003); Excellent Youth Innovation Team of Shandong Provincial Higher Education Institutions (2022KJ012); Taishan Scholars Program of Shandong Province (tsqn202312328); and the **an Science and Technology Bureau (grant number: 202228079). The funders were not involved in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, or the writing or submitting of this report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Qilu Hospital of Shandong University (approval number KYLL-202011(KS)-239). The study was conducted in compliance with the ethical standards set by national and institutional committees on human experimentation, as well as the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 (revised in 2008).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, W., Wang, Y., Wang, F. et al. Notable dysthymia: evolving trends of major depressive disorders and dysthymia in China from 1990 to 2019, and projections until 2030. BMC Public Health 24, 1585 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-18943-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-18943-7