Abstract

Background

Anaemia is a reduction in haemoglobin concentration below a threshold, resulting from various factors including severe blood loss during and after childbirth. Symptoms of anaemia include fatigue and weakness, among others, affecting health and quality of life. Anaemic pregnant women have an increased risk of premature delivery, a low-birthweight infant, and postpartum depression. They are also more likely to have anaemia in the postpartum period which can lead to an ongoing condition and affect subsequent pregnancies. In 2019 nearly 37% of pregnant women globally had anaemia, and estimates suggest that 50–80% of postpartum women in low- and middle-income countries have anaemia, but currently there is no standard measurement or classification for postpartum anaemia.

Methods

A rapid landscape review was conducted to identify and characterize postpartum anaemia measurement searching references within three published systematic reviews of anaemia, including studies published between 2012 and 2021. We then conducted a new search for relevant literature from February 2021 to April 2022 in EMBASE and MEDLINE using a similar search strategy as used in the published reviews.

Results

In total, we identified 53 relevant studies. The timing of haemoglobin measurement ranged from within the immediate postpartum period to over 6 weeks. The thresholds used to diagnose anaemia in postpartum women varied considerably, with < 120, < 110, < 100 and < 80 g/L the most frequently reported. Other laboratory results frequently reported included ferritin and transferrin receptor. Clinical outcomes reported in 32 out of 53 studies included postpartum depression, quality of life, and fatigue. Haemoglobin measurements were performed in a laboratory, although it is unclear from the studies if venous samples and automatic analysers were used in all cases.

Conclusions

This review demonstrates the need for improving postpartum anaemia measurement given the variability observed in published measures. With the high prevalence of anaemia, the relatively simple treatment for non-severe cases of iron deficiency anaemia, and its importance to public health with multi-generational effects, it is crucial to develop common measures for women in the postpartum period and promote rapid uptake and reporting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Anaemia is defined as a reduction in haemoglobin concentration below a threshold and can result from various factors including micronutrient deficiencies, inherited haemoglobinopathies, chronic infection, parasitic infection and blood loss [1]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), it occurs when “the number of red blood cells…is insufficient to meet the body’s physiologic needs,” ([2]; p.1) which varies with age, gender, altitude, smoking, and stage of pregnancy. It is currently defined as having a haemoglobin concentration less than 120 g/L for non-pregnant and lactating women, and less than 110 g/L for pregnant women, adjusted for altitude and smoking [2, 3]. WHO’s thresholds to define anaemia across many populations are currently under review [4]; a recent study pooling data from multiple countries found the WHO cut-offs were higher than the 5th percentile of nearly all countries, suggesting that lower cut-offs can be considered to define anaemia for children and non-pregnant women [5]. Accurate measurement is a critical component of appropriate care and understanding the global burden of morbidity [6].

Anaemia is prevalent among women and adolescent girls globally [3] and can be classified by type: micronutrient deficiencies (including iron); inflammation, aplastic, bone marrow disease, hemolytic, and sickle cell [7]. Symptoms of anaemia include fatigue, weakness, irregular heartbeats, dizziness, chest pain, and headaches, among others [7]. Anaemic women who are pregnant have an increased risk of premature delivery, a low-birthweight infant, and postpartum depression, and are more likely to have anaemia in the postpartum period [8] which can continue and affect haemoglobin levels in a subsequent pregnancy. In 2019, the global prevalence of anemia in pregnant women was nearly 37% [9]. Severe bleeding during and after childbirth can create or worsen an existing condition [10, 11]. Postpartum hemorrhage is the most common and dangerous complication of childbirth, causing 27% of maternal deaths [12] and affecting 5–10% of all births [13], contributing to postpartum anaemia. Among postpartum women in low- and middle-income countries, 50–80% are estimated to have anaemia [14].

Both postpartum hemorrhage and maternal anaemia may contribute to insufficient breastmilk supply [15, 16] with the latter also linked to a shorter duration of breastfeeding [16]. A study in Ethiopia found that 22% of lactating women were anaemic [17]; in eastern Uganda, 64% of women with a child less than one year of age were anaemic [18]. A study from South Africa found associations between iron status and depression, stress, and cognitive function among postpartum women [19]. Where anaemia is associated with breastfeeding challenges, both women’s and children’s health could be negatively affected, given the benefits that breastfeeding conveys [20].

Mild to moderate anaemia is most commonly treated orally with iron supplementation, with tablets easily dispensed during health care appointments e.g., for pre- or post-natal care, or home visits. Table 1 provides an overview of haemoglobin thresholds for anaemia severity at sea level. The prevalence of anaemia among postpartum women is currently unknown, and the condition is likely undertreated, threatening women’s and children’s health in the immediate postpartum period and long-term, including subsequent pregnancies, creating a continuous and multigenerational cycle of poor health and suboptimal growth.

The morbidity subgroup of WHO’s Mother and Newborn Information for Tracking Outcomes and Results (MoNITOR) advisory group [21] undertook this rapid landscape review of an understudied subpopulation within recent systematic reviews to produce an accelerated synthesis of evidence that identifies and characterizes postpartum anaemia measurement at three time points: the first 6 weeks, 6, and 12 months postpartum. This information informed the advisory group which was assembled for a time-limited term.

Methods

This rapid landscape review provides information about measurement characteristics and methods for postpartum anaemia and associated outcomes, which are important for characterising common co-morbidities experienced by postpartum women with anaemia. Our rapid review follows this definition: a “knowledge synthesis in which components of the systematic review process are simplified or omitted to produce information in a timely manner” ([22]; abstract) and employs abbreviated methods compared to a systematic review, including an accelerated and targeted approach to the search and selection of references [23]. We applied the following criteria to determine study inclusion and did not record excluded sources:

-

The study methods description clearly states that postpartum anaemia was identified and measured. Studies spanning the peripartum were also included provided it was clear that postpartum anaemia was identified.

-

The study was published between 2012 and 2022 to ensure that the most recent and relevant data were used. We extracted any relevant biochemical and clinical measures.

-

The study included women of reproductive age (between 15 and 49 years of age) in the postpartum period (up to 12 months).

-

The study was published in English.

-

The study involved human subjects only and was not published in the form of a letter, case report, or editorial.

We used three published systematic reviews to form the basis of the formal searches [10, 24, 25]. Using these published, peer reviewed, systematic reviews to identify relevant studies for this work provides a transparent and reproducible basis, should this work require updating. One Cochrane review [10] was designed to determine the optimum treatment strategy for postpartum anaemia. The searches for that review were carried out from database inception until April 2015 and by their nature were broad and encompassed the relevant literature for our review. Of note, within the study methods the authors clearly state that the review did not apply any restrictions on length of follow up in included studies to ensure long term benefits of harms of treatment were not excluded. Therefore, using the searches from this systematic review ensures that important studies published prior to 2015 are not missed in our review.

The second [24] was a systematic review of all the published trials in the field. Our purpose in using this one was to identify all the reported outcomes in the existing literature. This paper was the first step in the development of a minimum reporting standard for trials of iron interventions in pregnancy and the postpartum (a core outcome set), and as such, reports all the outcomes in the literature. That search strategy is described in Appendix S1 of that article [24].

The third [25], a comprehensive search of studies of anaemia in pregnancy and postpartum, was conducted from 2015 to 28th February 2021, building on other Cochrane reviews [10, 26] using the same search terms and strategies. Identifying relevant postpartum and peripartum studies from the search for that review [25] ensures that important recent studies were not missed.

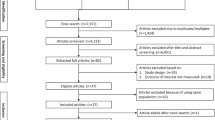

We conducted a final rapid search from Feb 2021 to April 2022 in EMBASE and MEDLINE using a search strategy similar to those used by the reviews previously cited to identify any final missing relevant studies published in the last year in any language. Figure 1 illustrates the sources of data for this rapid landscape review. One experienced reviewer conducted the search and discussed the findings with other authors. Relevant data about study design, measurement methods, and other parameters were extracted to a spreadsheet, reviewed, and discussed. We included our extraction matrix as Supplemental File 1.

Results

There were 53 studies included in the review (Table 2). Of these, 27 were randomised controlled trials, 21 were prospective cohorts, and five were retrospective cohort studies. Figure 2 shows where studies were conducted, most commonly in India (8 studies) and the USA (4), Tanzania (3) South Africa (3). The majority of studies were conducted with women in the postpartum period; however, there were four studies encompassing the antenatal, intrapartum and early postnatal period. Sample sizes of the studies ranged from 31 participants to cohorts over 11,000 individuals. In most studies, the type of anaemia was not specified and only hemoglobin measurement was reported in the published data (rather than other parameters such as hematocrit, mean cell volume, etc.). There were 15 studies where participants underwent objective testing to determine if the cause of anaemia was secondary to iron deficiency, largely through studies of iron indicies. The timing of anaemia measurement ranged from the immediate postpartum period to 6 weeks after delivery; no studies measured anaemia after 6 weeks postpartum.

Specifics on anaemia measurement

All included studies reported a reduction in haemoglobin below a particular threshold as a diagnosis of postpartum anaemia. In > 90% of the studies, haemoglobin measurement was carried out within a research setting. There were six studies where haemoglobin measurement was carried out for the purposes of clinical care and subsequently reported within a published paper. Two studies measured haemoglobin in the home setting, using available point of care tests.

Haemoglobin thresholds used for postpartum anaemia

Haemoglobin thresholds used to identify anaemia in postpartum women varied considerably in the included studies (Fig. 3). Thresholds of < 120 g/L, < 110 g/L, < 100 g/L and < 80 g/L were the most commonly used. However, there were several studies that reported ranges of thresholds to demonstrate anaemia such as 50-99 g/L and 90-115 g/L to name just two ranges used.

Measurement tools for postpartum anaemia

Haemoglobin levels (Table 2) were most commonly measured using a venous blood sample drawn and analysed within a biochemistry laboratory (36 out of 53 studies). The majority of studies provided no details on whether international standards for laboratory haemoglobin measurement were followed. Of the six studies reporting the use of point of care tests, all but one used a Haemocue® machine for such measurement. There were six studies where no specific details on the measurement tools used were provided in the published manuscripts.

There is variation in results from different measurement tools and a lack of evidence of test accuracy for alternative methods. Test accuracy studies of point of care tests compared to existing gold standards in postpartum women are unavailable. These data are needed as there is a contraction of circulating blood volume in postpartum women, therefore potentially affecting the measured values. Point of care tests compared to gold standard measurement tools require accuracy testing before they can be widely used. In addition, point of care test devices will require servicing and calibration when used.

Maternal clinical and biochemical parameters (outcomes)

The majority of the included studies provided details on maternal biochemical parameters. For the most part, these included haemoglobin levels following iron treatment, or another intervention. Many studies also reported changes to iron indices as outcomes of iron interventions (mainly serum ferritin and transferrin receptor).

Maternal clinical parameters were less commonly reported, in only 32 out of 53 studies. Postpartum depression, quality of life and fatigue were the most commonly reported clinical parameters. For postpartum depression, the most commonly used measurement tool was the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Score (EPDS) [79]. There was variation in the use of thresholds used from the score to identify postpartum depression. There were also reports using translated versions of the tool in settings where English was not the primary language. This occurred in three out of the eight included studies that used the EPDS. Fatigue was most commonly measured using the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory [80]. This is used in five studies, all of which were carried out in high income settings. Quality of life was reported in four studies, using the SF-36 tool [81] to measure changes in quality of life across the postpartum period.

In addition, breastfeeding was also reported (self-reported) in six studies and provided as an event rate. Breastfeeding rates were typically measured at 6 weeks postpartum, but also at 28 days and 12 weeks postpartum in two studies.

Infant parameters

Besides birth weight and gestational age at delivery, infant parameters were not commonly reported in the included studies. There were two studies of infant developmental milestones measured in South Africa using the Griffiths scale [82]. These two studies appeared to be linked and involved many of the same study authors.

Discussion

Controlling the global burden of anaemia is an important public health priority: the 2025 Global Nutrition Targets pursue a 50% reduction in the prevalence of anaemia in women of reproductive age, while the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals 2 (End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture) and 3 (Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages) encompass alleviation of anaemia [83, 84]. Nutrition-specific and -sensitive interventions aimed at alleviating the burden of anaemia are advised for many low-, middle-, and high-income countries worldwide (e.g., [85]), and decisions to implement these interventions and their monitoring is founded on measuring the prevalence of anaemia and distribution in different segments of the population, notably the most vulnerable groups such as women, adolescents and children.

Monitoring postpartum health is crucial to ensure optimal health and well-being for mothers and infants [86]. This review demonstrates the need for improving postpartum anaemia measurement given the variability observed in published measures. We found that measurement of anaemia in the postpartum period varies widely, with < 120 g/L, < 110 g/L, < 100 g/L and < 80 g/L the thresholds most frequently reported. Most measurements were reported from a research, rather than a clinical- or population-based monitoring, setting, and lacked details about how haemoglobin measurement was carried out. Laboratory testing was most frequently reported as the measurement method; there were just a few reports using point-of-care tests, and the accuracy of those tests requires further study. In addition, morbidities often associated with anaemia, such as fatigue, depression, and breastfeeding difficulties, were not commonly reported by the studies in this review.

Precise and accurate diagnosis of anaemia is required to provide timely and correct treatment if needed, not only for the implications on women’s health, but also for the economic and resource implications of an incorrect diagnosis, whether false positive or false negative [4]. Haemoglobin thresholds during the postpartum period should be standardized to facilitate understanding of the true burden in local and global contexts. Next steps include incorporating measurement of postpartum anaemia in global anaemia measurement consultations such as those seeking to standardize anaemia thresholds across the lifespan, and improving or ensuring the reporting of anaemia measurement in studies. At this time, the best practice for haemoglobin determination is the use of venous blood, automated haematology analysers, and high-quality control measures. In all cases, the source, method of sample collection and method used for haemoglobin determination should be included in any report of anaemia prevalence at individual or population level. Researchers and stakeholders should be aware that data obtained using different blood sources and/or methods would not necessarily be comparable.

Anaemia during the postpartum period may have long-term health implications for the mother and her infant [11]. To increase opportunities for measurement, implementation research on point of care tests, including feasibility, availability, and acceptability is needed, along with test accuracy assessments. The measurement of clinical endpoints or morbidities associated with postpartum anaemia is needed for both women and infants. This should include measures of fatigue, weakness, breastfeeding challenges, and postpartum depression for mothers and low birthweight, preterm delivery, and breastfeeding challenges for infants.

Standard postpartum guidelines are important to help healthcare provider give adequate care and monitoring of postnatal women. Implementation of WHO guideline [87] to continue daily supplementation of oral iron and folic acid for 3 months in the postpartum period is an effective intervention in most settings. While antenatal iron supplementation is typically measured in population-based surveys, there is a missed opportunity to measure postpartum supplementation, which will provide further insight into opportunities to mitigate the burden of this morbidity. In addition, other causes of anaemia should be considered and addressed. Although iron deficiency is a major cause of postpartum anaemia [11], it is important to consider not only the reasons for the lack of iron (such as, due to significant blood loss), but also other causes, including nutrients deficiencies, and social, demographic and economic factors as either or both causes and coadjutants for anaemia [88].

One strength of this study was its efficient approach to finding relevant resources. We used previously published systematic reviews on topics that encompassed our specific question to identify articles including postpartum anaemia measurement. We then conducted a search for the recent timeframe not covered by the reviews. This is not a systematic review so there may be some missed resources; however, we believe that our methods enabled a thorough rapid report about postpartum anaemia measurement.

Conclusions

There is marked variation in the haemoglobin thresholds used to define anaemia in women in the postpartum period. The most commonly used tool for haemoglobin measurement is a laboratory haemoglobin, with some recent use of point of care tests. The accuracy of these tests compared to the current gold standard (laboratory measure) is unknown. Clinical parameters for both women and infants are not widely reported in studies of postpartum anaemia. Anaemia and associated morbidities should be assessed, treated, and monitored to improve individual and population health. Given the high prevalence of anaemia, the relatively simple treatment for non-severe cases of iron deficiency anaemia, and its importance to public health, it is crucial to develop common measures obtained through easy methods and promote rapid uptake and reporting.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- EPDS:

-

Edinburgh postnatal depression score

- MoNITOR:

-

Mother and Newborn Information for Tracking Outcomes and Results

- NR:

-

Not reported

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

WHO. Nutritional anaemias: tools for effective prevention and control. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017.

WHO. Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity. Vitamin and Mineral Nutrition Information System. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2011 (WHO/NMH/NHD/MNM/11.1). http://www.who.int/vmnis/indicators/haemoglobin.pdf. Accessed 7 Aug 2022.

WHO. Global Health Observatory. https://www.who.int/data/gho. Accessed 15 June 2021.

Garcia-Casal MN, Pasricha SR, Sharma AJ, Peña-Rosas JP. Use and interpretation of hemoglobin concentrations for assessing anemia status in individuals and populations: results from a WHO technical meeting. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2019;1450:5–14.

Addo OY, Yu EX, Williams AM, Young MF, Sharma AJ, Mei Z, et al. Evaluation of hemoglobin cutoff levels to define anemia among health individuals. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2119123.

Pasricha SR, Colman K, Centeno-Tablante E, Garcia-Casal MN, Peña-Rosas JP. Revisiting WHO haemoglobin thresholds to define anaemia in clinical medicine and public health. Lancet Haemotol. 2018;5:E60–2.

Mayo Clinic. 2022. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/anemia/symptoms-causes/syc-20351360; and https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/pregnancy-week-by-week/in-depth/anemia-during-pregnancy/art20114455#:~:text=Severe%20iron%20deficiency%20anemia%20during,weight%20baby%20and%20postpartum%20depression. Accessed 31 Jul 2022.

WHO. Guideline: Iron supplementation in postpartum women. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549585. Accessed 12 Apr 2023.

WHO. 2022. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/anaemia_in_women_and_children#:~:text=In%202019%2C%20global%20anaemia%20prevalence,39.1%25)%20in%20pregnant%20women. Accessed 31 Jul 2022.

Markova V, Norgaard A, Jorgensen KJ, Langhoff-Roos J. 2015. Treatment for women with postpartum iron deficiency anaemia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010861.pub2/full. Accessed 27 Sept 2022.

Milman N. Postpartum anemia II: prevention and treatment. Ann Hematol. 2012;91:143–54.

Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, Tuncalp O, Moller AB, Daniels J, et al. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2:e323–33.

Deneax-Tharaux BM-P, Tort J. Epidemiology of post-partum haemorrhage. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2014;43:936–50.

Milman N. Postpartum anemia I: definition, prevalence, causes, and consequences. Ann Hematol. 2011;90:1247–53.

Willis CE, Livingstone V. Infant insufficient milk syndrome associated with maternal postpartum hemorrhage. J Hum Lact. 1995;11:123–6.

Henly SJ, Anderson CM, Avery MD, Hills-Bonczyk SG, Potter S, Duckett LJ. Anemia and insufficient milk in first-time mothers. Birth. 1995;22:86–92.

Lakew Y, Biadgilign S, Haile D. Anaemia prevalence and associated factors among lactating mothers in Ethiopia: evidence from the 2005 and 2011 demographic and health surveys. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006001.

Sserunjogi L, Scheut F, Whyte SR. Postnatal anaemia: neglected problems and missed opportunities in Uganda. Health Policy Plan. 2003;18:225–31.

Beard JL, Hendricks MK, Perez EM, Murray-Kolb L, Berg A, Vernon-Feagans L, et al. Maternal iron deficiency anemia affects postpartum emotions and cognition. J Nutr. 2005;135:267–72.

Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJ, França GV, Horton S, Krasevec J, Lancet Breastfeeding Series Group, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016;387:475–90.

WHO’s Mother and Newborn Information for Tracking Outcomes and Results (MoNITOR) technical advisory group. 2022. https://platform.who.int/data/maternal-newborn-child-adolescent-ageing/advisory-groups/monitor. Accessed 8 Aug 2022.

Tricco AC, Anton J, Zarin W, Strifler L, Ghassemi M, Ivory J, et al. A sco** review of rapid review methods. BMC Med. 2015;13:224.

Stevens A, Garritty C, Hersi M, Moher D. 2018. Develo** PRISMA-RR, a reporting guideline for rapid reviews of primary studies (Protocol). https://www.equator-network.org/library/reporting-guidelines-under-development/reporting-guidelines-under-development-for-systematic-reviews/#51. Accessed 8 June 2023.

Malinowski AK, D’Souza R, Khan KS, Shehata N, Malinowski M, Daru J. Reported outcomes in perinatal iron deficiency anemia trials: a systematic review. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2019;84:417.

Rogozińska E, Daru J, Nicolaides M, Amezcua-Prieto C, Robinson S, Wang R, et al. Iron preparations for women of reproductive age with iron deficiency anaemia in pregnancy (FRIDA): a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Haematol. 2021;8:e503–12.

Peña-Rosas JP, De-Regil LM, Garcia-Casal MN, Dowswell T. Daily oral iron supplementation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(7):CD004736.

Froessler B, Cocchiaro C, Saadat-Gilani K, Hodyl N, Dekker G. Intravenous iron sucrose versus oral iron ferrous sulfate for antenatal and postpartum iron deficiency anemia: a randomized trial. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;26:654–9.

Bhandal N, Russell R. Intravenous versus oral iron therapy for postpartum anaemia. BJOG. 2006;113:1248–52.

Daniilidis A, Giannoulis C, Pantelis A, Tantanasis T, Dinas K. Total infusion of low molecular weight iron-dextran for treating postpartum anemia. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2011;38:159–61.

Mumtaz A, Farooq F. Comparison for Effects of Intravenous versus Oral Iron Therapy for Postpartum Anemia. Pakistan J Med Health Sci. 2011;5(1):116–20.

Murray-Kolb LE, Beard JL. Iron deficiency and child and maternal health. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:946S-950S.

Perez EM, Hendricks MK, Beard JL, Murray-Kolb LE, Berg A, Tomlinson M, et al. Mother-infant interactions and infant development are altered by maternal iron deficiency anemia. J Nutr. 2005;135:850–5.

Guerra Gutiérrez CE, Muñoz Paredes PA, Ospino Muñoz AM, Varela Púa AN, Vega HL. Morbidity and mortality maternal health in an institution 2012. Revista Salud Uninorte. 2014;30:217–26.

Jain G, Palaria U, Jha SK. Intravenous Iron in Postpartum Anemia. J Obstet Gynecol India. 2013;63:45–8.

Krafft A, Breymann C. Iron sucrose with and without recombinant erythropoietin for the treatment of severe postpartum anemia: a prospective, randomized, open-label study. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2011;37:119–24.

Perelló MF, Coloma JL, Masoller N, Esteve J, Palacio M. Intravenous ferrous sucrose versus placebo in addition to oral iron therapy for the treatment of severe postpartum anaemia: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2014;121:706–13.

Prick BW, Jansen AJG, Steegers EAP, Hop WCJ, Essink-Bot ML, Uyl-De Groot CA, et al. Transfusion policy after severe postpartum haemorrhage: a randomised non-inferiority trial. BJOG. 2014;121:1005–14.

Seid MH, Derman RJ, Baker JB, Banach W, Goldberg C, Rogers R. Ferric carboxymaltose injection in the treatment of postpartum iron deficiency anemia: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:435-e1.

Tam KF, Lee CP, Pun TC. Mild postnatal anemia: is it a problem? Am J Perinatol. 2005;22:345–9.

Van Wyck DB, Martens MG, Seid MH, Baker JB, Mangione A. Intravenous ferric carboxymaltose compared with oral iron in the treatment of postpartum anemia: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:267–78.

Verma U, Singh A, Chandra M, Chandra M, Garg R, Singh S, et al. To evaluate the efficacy and safety of single dose intravenous iron carboxymaltose verses multidose iron sucrose in post-partum cases of severe iron deficiency anemia. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2015;4:442–6.

Wågström E, Åkesson A, Van Rooijen M, Larson B, Bremme K. Erythropoietin and intravenous iron therapy in postpartum anaemia. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86:957–62.

Westad S, Backe B, Salvesen KÅ, Nakling J, Økland I, Borthen I, et al. A 12-week randomised study comparing intravenous iron sucrose versus oral ferrous sulphate for treatment of postpartum anemia. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008;87:916–23.

Backe B. A 6-week randomised, open comparative, multi-centre study of intravenous ferric carboxymaltose (ferinject) and oral iron (duroferon) for treatment of post partum anemia. 2009; http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT00929409. Accessed 21 Oct 2022.

Chaudhuri P. Intravenous iron-sucrose complex versus oral iron in the treatment of postpartum anemia. Clinical Trials Registry - India 2013. Published data only, as cited in Markova et al. 2015. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [10].

Holm C, Thomsen LL, Norgaard A, Langhoff-Roos J. Single-dose intravenous iron infusion or oral iron for treatment of fatigue after postpartum haemorrhage: a randomized controlled trial. Vox Sang. 2017;112:219–28.

Hossain N. Use of iron isomaltoside 1000 (Monofer) in postpartum anemia. ClinicalTrials.gov 2013. Published data only, as cited in Markova et al. 2015, Cochrane Database Syst Rev [10].

Suneja A. A clinical trial to compare oral iron ferrous sulfate with newer intravenous iron (ferric carboxymaltose) injection in patients of iron deficiency anemia in post delivery period. Clinical Trials Registry - India (http://ctri.nic.in) 2014. Published data only, as cited in Markova et al. 2015, Cochrane Database Syst Rev [10].

Breymann C, von Seefried B, Stahel M, Geisser P, Canclini C. Milk iron content in breast-feeding mothers after administration of intravenous iron sucrose complex. J Perinat Med. 2007;35:115–8.

Dede A, Uygur D, Yilmaz B, Mungan T, Uǧur M. Intravenous iron sucrose complex vs. oral ferrous sulfate for postpartum iron deficiency anemia. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2005;90:238–9.

Haidar J, Umeta M, Kogi-Makau W. Effect of iron supplementation on serum zinc status of lactating women in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. East Afr Med J. 2005;82:349–52.

Mitra AK, Khoury AJ. Universal iron supplementation: a simple and effective strategy to reduce anaemia among low-income, postpartum women. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15:546–53.

Van der Woude D. Postpartum women with micronutrient deficiency: health status and fatigue. 2015; https://pure.uvt.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/6971236/Van_der_Woude_Postpartum_19_06_2015.pdf. Accessed 29 Sept 2022.

Zhao A, Zhang J, Wu W, Wang P, Zhan Y. Postpartum anemia is a neglected public health issue in China: a cross-sectional study. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2019;28:793–9.

Kant S, Kaur R, Ahamed F, Singh A, Malhotra S, Kumar R. Effectiveness of intravenous ferric carboxymaltose in improving hemoglobin level among postpartum women with moderate-to-severe anemia at a secondary care hospital in Faridabad, Haryana - An interventional study. Indian J Public Health. 2020;64:168–72.

Chandrasekaran N, de Souza LR, Urquia ML, Young B, McLeod A, Windrim R, et al. Is anemia an independent risk factor for postpartum depression in women who have a cesarean section? - A prospective observational study 11 Medical and Health Sciences 1117 Public Health and Health Services. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):400.

Kaur R, Kant S, Haldar P, Ahamed F, Singh A, Dwarakanathan V, et al. Single dose of intravenous ferric carboxymaltose prevents anemia for 6 months among moderately or severely anemic postpartum women: a case study from India. Curr Dev Nutr. 2021;5(7):nzab078.

Yefet E, Yossef A, Massalha M, Suleiman A, Hatokay A, Kamhine-Yefet M, et al. Relationship between patient ethnicity and prevalence of anemia during pregnancy and the puerperium period and compliance with healthcare recommendations - implications for targeted health policy. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2020;9:71. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13584-020-00423-z.

Selvaraj R, Ramakrishnan J, Sahu S, Kar S, Laksham K, Premarajan K, et al. High prevalence of anemia among postnatal mothers in Urban Puducherry: A community-based study. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8:2703. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_386_19.

Hye RA, Sayeeda N, Islam GMR, Mitu JF, Zaman MS. Intravenous iron sucrose vs. blood transfusion in the management of moderate postpartum iron deficiency anemia: A non-randomized quasi-experimental study. Heliyon. 2022;8(2):e08980.

Liyew AM, Kebede SA, Agegnehu CD, Teshale AB, Alem AZ, Yeshaw Y, et al. Spatiotemporal patterns of anemia among lactating mothers in Ethiopia using data from Ethiopian demographic and health surveys (2005, 2011 and 2016). PLoS ONE. 2020;15(8):e0237147.

Koyuncu K, Turgay B, Şükür YE, Yɪldɪrɪm B, Ateş C, Söylemez F. Third trimester anemia extends the length of hospital stay after delivery. Tur J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;14:166–9.

Mremi A, Rwenyagila D, Mlay J. Prevalence of post-partum anemia and associated factors among women attending public primary health care facilities: An institutional based cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2022;17(2):e026350.

Tairo SR, Munyogwa MJ. Maternal anaemia during postpartum: preliminary findings from a cross-sectional study in Dodoma City. Tanzania Nurs Open. 2022;9:458–66.

Vanobberghen F, Lweno O, Kuemmerle A, Mwebi KD, Asilia P, Issa A, et al. Efficacy and safety of intravenous ferric carboxymaltose compared with oral iron for the treatment of iron deficiency anaemia in women after childbirth in Tanzania: a parallel-group, open-label, randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9:e189-98.

Sharma N, Thiek JL, Natung T, Ahanthem SS. Comparative study of efficacy and safety of ferric carboxymaltose versus iron sucrose in post-partum anaemia. J Obstet Gynecol India. 2017;67:253–7.

Iancu AM, Buckstein J, Melamed N, Lin Y. Examining prescribing practices with respect to oral iron supplementation for post-partum anemia: a retrospective review. J Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2021. 29

Rubio-Álvarez A, Molina-Alarcón M, Hernández-Martínez A. Incidence of postpartum anaemia and risk factors associated with vaginal birth. Women and Birth. 2018;31:158–65.

Garrido CM, León J, Vidal AR. Maternal anaemia after delivery: prevalence and risk factors. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;38:55–9.

Paoletti AM, Orrù MM, Marotto MF, Pilloni M, Zedda P, Fais MF, et al. Observational study on the efficacy of the supplementation with a preparation with several minerals and vitamins in improving mood and behaviour of healthy puerperal women. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2013;29:779–83.

Infante-Torres N, Molina-Alarcón M, Rubio-Álvarez A, Rodríguez-Almagro J, Hernández-Martínez A. Relationship between duration of second stage of labour and postpartum anaemia. Women and Birth. 2018;31:e318-24.

Miller CM, Ramachandran B, Akbar K, Carvalho B, Butwick AJ. The impact of postpartum hemoglobin levels on maternal quality of life after delivery: a prospective exploratory study. Ann Hematol. 2016;95:2049–55.

Maeda Y, Ogawa K, Morisaki N, Tachibana Y, Horikawa R, Sago H. Association between perinatal anemia and postpartum depression: a prospective cohort study of Japanese women. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2020;148:48–52.

Eckerdal P, Kollia N, Löfblad J, Hellgren C, Karlsson L, Högberg U, et al. Delineating the association between heavy postpartum haemorrhage and postpartum depression. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0144274.

Goshtasebi A, Alizadeh M, Gandevani SB. Association between maternal anaemia and postpartum depression in an urban sample of pregnant women in Iran. J Health Popul Nutr. 2013;31:398.

Alharbi AA, Abdulghani HM. Risk factors associated with postpartum depression in the Saudi population. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014;10:311–6.

Armony-Sivan R, Shao J, Li M, Zhao G, Zhao Z, Xu G, et al. No relationship between maternal iron status and postpartum depression in two samples in China. J Pregnancy. 2012;2012:521431.

Corwin EJ, Murray-Kolb LE, Beard JL. Human nutrition and metabolism research communication low hemoglobin level is a risk factor for postpartum depression. J Nutr. 2003;133:4139–42.

Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. BJPsych. 1987;150:782–6.

Smets EMA, Garssen B, Bonke B, De Haes JCJM. The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39:315–25.

RAND Corporation 2022. https://www.rand.org/health-care/surveys_tools/mos/36-item-short-form.html. Accessed 7 Aug 2022.

Luiz DM, Foxcroft CD, Stewart R. The construct validity of the Griffiths scales of mental development. Child Care Health Dev. 2001;27:73–83.

WHO. Global Nutrition Targets. 2022. https://www.who.int/teams/nutrition-and-food-safety/global-targets-2025. Accessed 25 Sept 2022.

WHO. Sustainable Development Goals. 2022. https://sdgs.un.org/goals. Accessed 25 Sept 2022.

Scott N, Delport D, Hainsworth S, Pearson R, Morgan C, Huang S, et al. Ending malnutrition in all its forms requires scaling up proven nutrition interventions and much more: a 129-country analysis. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):356.

Walker LO, Murphey CL, Nichols F. The broken thread of health promotion and disease prevention for women during the postpartum period. JPE. 2015;24(2):81–92.

WHO. Recommendations on maternal and newborn care for a positive postnatal experience. 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240045989. Accessed 25 Sept 2022.

WHO. Nutritional anaemias: tools for effective prevention and control. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Vaibhav Patwardhan, Research Officer, Jhpiego India country office for assistance with formatting references.

Funding

This work received support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation as part of the Mother and Newborn Information for Tracking Outcomes and Results (MoNITOR) Advisory Group. This work was supported, in whole or in part, by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation INV-001527 (Opportunity ID). Under the grant conditions of the Foundation, a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Generic License has already been assigned to the Author Accepted Manuscript version that might arise from this submission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JY, HO, GU, KS, and JD conceptualized the study; JD conducted the search and assembled data; JY and JD wrote the first draft of the manuscript; all authors provided critical reviews and contributed to subsequent manuscript drafts; all authors have approved the submitted version of the manuscript. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. This study uses previously published data and does not involve human subjects.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yourkavitch, J., Obara, H., Usmanova, G. et al. A rapid landscape review of postpartum anaemia measurement: challenges and opportunities. BMC Public Health 23, 1454 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16383-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16383-3