Abstract

Background

The earned income tax credit (EITC) is the largest U.S. poverty alleviation program for low-income families, disbursed annually as a lump-sum tax refund. Despite its well-documented health impacts, the mechanisms through which the EITC affects health are not well understood. The objective of this analysis was to examine self-reported spending patterns of tax refunds among EITC recipients to clarify potential pathways through which income may affect health.

Methods

We first examined spending patterns among 2020–2021 Assessing California Communities’ Experiences with Safety Net Supports (ACCESS) study participants (N = 241) and then stratified the analysis by key demographic subgroups.

Results

More than half of EITC recipients reported spending their tax refunds on bills and debt (52.3%), followed by 49.4% on housing, and 37.8% on vehicles. Only 3.3% reported spending on healthcare. (Note: respondents could list more than one possible spending category.) Participants ages 30 + were more likely to spend on bills and debt relative to those ages 18–29 (57.6% versus 39.4%, respectively). Other subgroup analyses did not yield significant findings.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that EITC recipients primarily use their refunds on bills and debt, as well as on household and vehicle expenses. This supports the idea of the EITC as a safety net policy which addresses key social determinants of health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Poverty is a prevalent and persistent determinant of poor health [1]. The earned income tax credit (EITC) is the largest U.S. poverty alleviation program for families with children, disbursed in the form of a tax refund to working families with low income [2,3,4]. The EITC aims to reduce poverty while incentivizing employment. Younger, single, female heads of household with low educational attainment comprise the majority of EITC recipients [2, 5]. Disbursed as an annual lump-sum tax refund, the EITC amount for each family varies by earned income, marital status, and number of dependent children, with the mean federal refund at $2,411 in 2021 [5]. The EITC has positive effects on labor supply and income, and has also shown benefits for numerous health outcomes including infant birthweight, adult mental health, and food security [5,6,7,8,9].

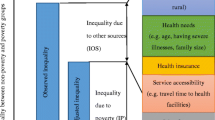

The hypothesized pathways through which the EITC may affect health include the family investment mechanism (i.e., families have more money to spend on inputs like nutrition and healthcare) and the family stress model (i.e., depression and stress are lower because of greater household resources) [10]. Yet, there has been limited research on how EITC recipients actually spend their refunds [11, 12]. One prior study using the 1997–2006 waves of the Consumer Expenditure Survey found that households likely to be EITC recipients more often spent their money during tax season on durable goods—and particularly big-ticket items like household appliances—compared with other households [13]. Another survey of 200 EITC recipients in 2007 found over half of families intended to spend the refund on savings, although only 39% did so, while 84% paid down bills and debts [14]. To address this knowledge gap, we conducted a cross-sectional survey of a diverse sample of EITC-eligible California families to understand spending patterns and enhance understanding of this critical policy’s health effects.

Methods

Data collection

Data were drawn from the Assessing California Communities’ Experiences with Safety Net Supports (ACCESS) Study, which involved survey-based interviews with EITC-eligible California families with children during August 2020-May 2021 (N = 241). Study procedures for the ACCESS Study have been described previously [15]. For the purposes of this sub-study, the sample was restricted to individuals who had their 2019 tax returns available for review, to confirm receipt of the EITC. All study protocols were approved by the California Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects and the University of California, Berkeley institutional review board. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Survey implementation

The survey included questions on sociodemographic characteristics and data from tax forms. Participants self-identified their race/ethnicity, and this was categorized into Hispanic/Latinx, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, and non-Hispanic other. EITC recipients were asked how they spent their 2019 tax refunds, which they would have received in early 2020. This was included as an open-ended question, and interviewers marked responses mentioned by recipients from the following list of 12 spending categories: housing (e.g., mortgage, rent), utilities, home-related repairs or improvements (e.g., construction, appliances), clothing, vehicle-related expenses, healthcare and health insurance payments, non-health insurance policies, educational expenses, entertainment expenses, food and beverages, savings and investments, or other (for which they would specify the expense). All responses designated as “other” were reviewed, cleaned, and further categorized by study staff, yielding three additional categories: bills, debt, and children’s needs. Respondents could list more than one possible spending category, and they might select two categories to represent a single expense (e.g., debt and education for an educational loan).

Finally, 11 categories were created by combining several categories noted above that addressed related concepts and collapsing them to: housing, vehicles, bills and debt, retail consumption, food, savings/investments, children’s needs, home repairs/improvements, education, healthcare and health insurance, and miscellaneous (Supplemental Table 1).

Data analysis

First, we calculated descriptive statistics. Then, we tabulated the percentage of participants who reported spending their refund on the categories above.

We also hypothesized that the EITC may be more valuable for individuals with fewer resources due to structural racism and discrimination, so we then stratified analyses by sociodemographic characteristics: age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, employment status, educational attainment, and refund size. Income and refund size were dichotomized by splitting them at the mean. We conducted two-tailed tests of proportions to assess whether spending was statistically significantly different across subgroups. Differences in spending patterns may inform our understanding of why larger health benefits have been observed for some groups, like Black women or those with lower educational attainment [16,17,18].

Results

Sample characteristics

Of the 241 participants, most (93.8%) were female (Table 1). Approximately half were Latinx/Hispanic, and one quarter Black. One-fifth had a bachelor’s degree or higher. Median annual adjusted gross income was $19,257 (IQR 11,718 − 30,000). One quarter of respondents reported being primarily unemployed in 2019; however, EITC income-specific eligibility was assessed at the household level (i.e., respondent + spouse), rather than at the individual level, so their household still earned enough income to qualify for the EITC. The median 2019 EITC amount was $3,194 (IQR 1,712-4,789). The mean 2019 EITC amounts nationally and in California were $2,461 and $2,297, respectively, although these included individuals without children, who receive smaller EITC benefits [2].

Refund spending

About half of respondents spent their refunds on bills and debt (52.3%) and housing (49.4%), followed by 37.8% on vehicles (Table 2). Savings and investments (10.4%), education (5.4%), and healthcare and health insurance (3.3%) were the least common. Respondents could list more than one possible spending category, so the total in this table sums to greater than 100%. In stratified analyses (Supplemental Table 2), there were generally no differences across spending categories based on participant characteristics; we summarize the few exceptions here. In subgroup analyses by race/ethnicity, participants of other races were more likely to spend their refund on education (16.7%, p = 0.03) and food/beverages (40.0%; p = 0.02) compared with Latinx, Black, and White participants. In subgroup analyses by age, study participants ages 30 or older were more likely to spend tax refunds on bills and debt compared with participants aged 18–29 (57.6% versus 39.4, p = 0.01). In subgroup analyses by employment status, employed participants were more likely to spend their refund on miscellaneous items (6.1%, p = 0.02) compared with unemployed participants. There were no differences in refund spending by income or EITC refund size.

Discussion

This study interviewed Californians with low income who were recipients of the EITC—the largest U.S. poverty alleviation program for families with children—to understand how they spent their tax refunds. Participants reported spending on basic needs like housing, vehicles, bills, and debt. California has a higher-than-average cost-of-living, with the median cost of housing at nearly twice the national average,[19] which likely explains housing as the second-largest spending category. Prior studies using administrative data and older surveys corroborate these findings, where recipients of the EITC and other income support programs allocated benefits to durable goods like cars or immediate concerns like bills [5, 13, 14]. Participants reported minimal spending on healthcare, similar to prior work finding no short-run changes in healthcare utilization after EITC receipt [20].

Few statistically significant subgroup differences emerged, perhaps due to the small sample size, or because spending was similar across subgroups. These few exceptions should be interpreted with caution in light of multiple hypothesis testing.

This study’s primary strength is the first-hand assessment of tax refund spending from actual EITC recipients as verified by review of tax returns. Limitations include recruitment through convenience sampling, so results may not be representative or generalizable. Additionally, data collection occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic; given the circumstances, spending may differ from pre-pandemic or post-pandemic periods (e.g., due to the receipt of stimulus checks), although this study provides insight into spending among vulnerable families during this critical time. Additionally, we did not ask for spending amounts in each category, nor itemized spending within categories, such as the exact type of debt being paid. This could potentially mask EITC spending on medical debt, a type of debt that makes up a large portion of debt collections and that increases in months with higher income [21, 22]. For this reason, we are unable to assess the connection between the EITC and health through medical debt. Finally, self-reported information may be subject to standard reporting biases, like social desirability.

Conclusion

Previous studies have found that the EITC improves health. By examining how EITC recipients spend their tax refunds and finding that the majority of spending on bills and debt, housing and vehicles, this study contributes evidence to understand the possible mechanisms for this association. Future research using larger samples could build on our exploratory subgroup analyses to examine whether individual- and area-level characteristics affect spending patterns.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACCESS:

-

Assessing California Communities’ Experiences with Safety Net Supports

- EITC:

-

Earned Income Tax Credit

References

Adler NE, Newman K. Socioeconomic disparities in health: pathways and policies. Health Aff. 2002;21(2):60–76.

U.S. Internal Revenue Service. Statistics for Tax Returns with the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). [https://www.eitc.irs.gov/eitc-central/statistics-for-tax-returns-with-eitc/statistics-for-tax-returns-with-the-earned-income]. Accessed July 13, 2023.

Hoynes HW, Patel AJ. Effective policy for reducing poverty and inequality? The earned income tax credit and the distribution of income. J Hum Resour 2018; 53(4):859–890..

Berger LM, Font SA, Slack KS, Waldfogel J. Income and child maltreatment in unmarried families: evidence from the earned income tax credit. Rev Econ Househ. 2017;15(4):1345–72.

Fisher J, Rehkopf DH. The Earned Income Tax Credit as supplementary food benefits and savings for durable goods. Contemporary Economic Policy 2022;40(3):439–455.

Jones LE, Wang G, Yilmazer T. The long-term effect of the earned income tax credit on women’s physical and mental health. Health Econ. 2022;31(6):1067–102.

Hamad R, Rehkopf DH. Poverty, pregnancy, and birth outcomes: a study of the earned income tax credit. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2015;29(5):444–52.

Shields-Zeeman L, Collin DF, Batra A, Hamad R. How does income affect mental health and health behaviors? A quasi-experimental study of the earned income tax credit. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2021;75:929–35.

Batra A, Hamad R. Short-term effects of the earned income tax credit on children’s physical and mental health. Ann Epidemiol. 2021;58:15–21.

Yeung WJ, Linver MR, Brooks-Gunn J. How money matters for young children’s development: parental investment and family processes. Child Dev. 2002;73(6):1861–79.

Crandall-Hollick ML. The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC): Legislative History. Congressional Research Service: Washington, D.C. April 28, 2022.

Pega F, Carter K, Blakely T, Lucas PJ. In-work tax credits for families and their impact on health status in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013(8):Cd009963.

Goodman-Bacon A, McGranahan L. How do EITC recipients spend their refunds? Econ Perspect; 2008, 32(2): 17-32.

Mendenhall R, Edin K, Crowley S, Sykes J, Tach L, Kriz K, Kling JR. The role of earned income tax credit in the Budgets of low-income households. Social Service Review. 2012;86(3):367–400.

Hamad R, Gosliner W, Brown EM, Hoskote M, Jackson K, Fernald LC. Understanding low take-up of poverty alleviation benefits among low-income Californians. Health Aff. 2022;41(12):1715–24.

Hoynes H, Miller D, Simon D. Income, the earned income tax credit, and infant health. Am Economic Journal: Economic Policy. 2015;7(1):172–211.

Komro KA, Markowitz S, Livingston MD, Wagenaar AC. Effects of State-Level Earned Income Tax Credit Laws on Birth Outcomes by Race and Ethnicity. Health Equity. 2019;3(1):61–7.

Batra A, Karasek D, Hamad R. Racial differences in the association between the U.S. Earned Income Tax Credit and birthweight. Women’s Health Issues. 2022;32(1):26–32.

U.S. Census Bureau. Housing. [https://www.census.gov/topics/housing.html] Accessed 13 July, 2023.

Hamad R, Niedzwiecki M. The short-term effects of the earned income tax credit on healthcare utilization. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(6):1295–304.

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Market snapshot: an update on third-party debt collections tradelines reporting. Washington, D.C. 2023.

Farrell D, Greig F. Co** with costs: Big data on expense volatility and medical payments. JP Morgan Chase Institute, 2017.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Elsa Esparza, Melissa Cortez, and Erika Brown for their administrative support, data management, and intellectual contributions during survey design, participant recruitment, and data collection. We also thank Allyson Velez, Daniel Salas, Dahlia Elkhalifa, Dalila Alvarado, Geremy Lowe, Heena Shah, Kelly Woods, Mina Mahdi, Sasha Narain, Simrit Dhillon, and Sofia Finestone for their support in data collection. Lastly, we thank the ACCESS Study Community Advisory Board and California State WIC program for their support in promoting and recruiting participants, and we thank the participants themselves for their time and insights.

Funding

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper. This study was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Tip** Point Foundation, the University of California Office of the President, and the Berkeley Population Center at the University of California Berkeley.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RH, LF, and WG conceived of the study. JY and KJ contributed to data analysis. RH and JY wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript critically for intellectual content and approved of the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All study protocols were approved by the California Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects and the University of California, Berkeley institutional review board. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hamad, R., Yeb, J., Jackson, K. et al. Potential mechanisms linking poverty alleviation and health: an analysis of benefit spending among recipients of the U.S. earned income tax credit. BMC Public Health 23, 1385 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16296-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16296-1