Abstract

Background

A recent systematic review reported that mild drinking showed beneficial effects on mortality. However, this relationship between alcohol consumption and mortality differs by race, and there are few studies on Koreans. In this study, we reviewed previous studies conducted on Koreans to investigate the association between mild drinking and mortality.

Methods

Four databases (Medline, Web of Science, KoreaMed, and DBpia) were searched. Studies investigating the risk of alcohol consumption on three types of mortality (all-cause mortality, cancer-related mortality, and cardiovascular mortality) for Koreans were included.

Results

A total of 16 studies assessed alcohol consumption as a risk factor for mortality. Nine studies reported on the risk of alcohol consumption in relation to all-cause mortality, eight to cancer-related mortality, and three to cardiovascular mortality. Among these, only studies assessing alcohol amount not drink status or drink frequency were included in meta-analysis. The results of the meta-analysis did not show a significant effect of mild alcohol consumption on all-cause mortality (5 studies, OR: 0.85, 95 % CI: 0.72, 1.01). While meta-analysis of studies using all-cancer mortality showed significant effect of alcohol consumption (4 studies, OR: 0.89, 95 % CI: 0.85, 0.94), results of studies including all-caner and specific type of cancer was not significant (7 studies, OR: 1.02, 95 % CI: 0.9, 1.15). Although a meta-analysis of cardiovascular mortality could not be conducted owing to a lack of studies, all studies reported a non-significant effect of occasional or mild alcohol consumption.

Discussion

In this study, mild alcohol consumption in Korean did not show beneficial effect on mortality and it might be caused by three factors: criterion of mild drinking, the subjects, and sample size. The criterion of mild alcohol consumption was diverse in included studies. The effect of alcohol consumption could differ based on subjects’ sex, age as well as race. In addition, the effect of alcohol consumption might be different from previous one due to the small number of studies.

Conclusions

Mild alcohol consumption did not show any beneficial effects in relation to all-cause, cancer-related, and cardiovascular mortality. Additional studies are necessary to verify any association between mild drinking and mortality in Koreans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Although alcohol abuse negatively affects health and mortality [1, 2], several studies reported that mild drinking has a beneficial effect on mortality, and depicted this relationship as a J-shaped curve [3–5]. In addition, recent meta-analyses have described how mild drinking had a beneficial effect on all-cause mortality [6], cardiovascular disease [7], and cancer-related mortality [8].

This association between alcohol and mortality might differ according to subjects’ characteristics. The dose of alcohol associated with protective effects on total mortality is lower among women than in men [6]. Rehm et al. reported a significant influence of drinking on mortality with a J-shaped association for males, but differences between drinking categories were much weaker for women [9]. In addition, the effect of alcohol might differ according to health status. A previous study reported that mild alcohol use may be beneficial for older adults in poor health, but not for those in good health [10]. Also, the effect of alcohol consumption on cardiovascular disease was different between men with and without hypertension [11].

Susceptibility to the effects of alcohol may also be contingent upon race [12]. Although mild alcohol consumption showed a beneficial effect on all-cause mortality in a previous study [6], in African Americans no J-shaped curve was found [13]. Meta-analysis of alcohol dose and total mortality reported a varying association between alcohol consumption and total mortality according to geographic region [6]. Although several studies have been conducted in East-Asian populations [14], there are few studies that focus specifically on Koreans. We therefore performed a systematic review to examine the relationship between mild alcohol consumption and mortality among Koreans.

Methods

Literature search and study inclusion criteria

We selected relevant published studies by searching Medline, Web of Science, KoreaMed, and DBPia databases up to September 30, 2014 without a restriction of study period. Search terms included “alcohol,” “mortality,” and “Korea.” All potentially eligible studies were considered for review, and the reference lists of included studies were examined. Only studies with Korean subjects were included. In addition, studies were eligible for inclusion only if they evaluated all-cause mortality, cancer-related mortality, or cardiovascular mortality as a result of alcohol consumption. When multiple articles had been published for a single study, the latest publication or study with more subjects was used. Two reviewers assessed relevant publications independently, and disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer. Extracted data included study design, study period, characteristics and number of participants, criteria for drinking, and the risk associated with alcohol consumption (PRISMA checklist - Additional file 1).

Data synthesis

For this meta-analysis, studies in which the risk of alcohol consumption was based only on status (e.g., non-drinker/former drinker/current drinker) or frequency were excluded when analyzing the risk of mild drinking. To summarize the effects of alcohol on mortality, we extracted the risk estimates and 95 % confidence intervals (CI) from each study using the Cochrane Collaboration software, Review Manager (version 5.2. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2012).

Although there is a consensus on moderate drinking as constituting up to one drink per day for women and up to two drinks per day for men [15], the range of alcohol intake showing a protective effect in previous meta-analyses was variable [6–8]. For this reason we compared the risk of non-drinkers and mild drinkers consuming the least alcohol, based on each study’s criteria. Chi-square, tau2, and Higgins I2 tests were used to assess heterogeneity. When notable heterogeneity was present (I2 index ≥ 80 %), a random-effects model was used.

Quality assessment and publication bias

Two independent reviewers critically appraised the methodological quality of included studies using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale is a quality assessment tool based on selection of cases and controls (0–4 points for case–control studies and 0–6 points for cohort studies), comparability (0–2 points), and exposure (0–4 points in case–control studies) or outcome (0–5 points in cohort studies). We defined the studies with less than 4 points in case–control studies and less than 6 points in cohort studies as low quality, and these were excluded from the meta-analysis.

Results

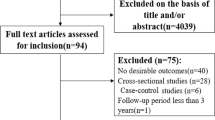

Of a total of 474 identified studies, 429 were excluded after reviewing article titles. Based on a review of abstracts another 29 studies were excluded, and 16 fulfilled the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Of 29 studies, 12 studies did not related to alcohol, 7 did not assess mortality, and subjects did not meet inclusion criteria in one study. We excluded three studies investigating mortality associated with alcohol disorder [2, 16, 17], because it is a disease and is not appropriate in the assessment of the effects of typical alcohol use. In addition, we excluded three studies because they used the same participants as other studies [18–20], and another three studies that did not include appropriate data [21–23].

The characteristics of included studies are summarized in Table 1. Of the 16 studies, five reported on all-cause mortality, six on cancer-related mortality, and one on cardiovascular mortality. Two studies reported all-cause and cancer-related mortality, and the remaining two reported on all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Ten of the 16 studies used weekly or daily amount as the measure of alcohol consumption, three used drinking frequency, and three used drinking status. A category of no alcohol intake was the reference category in 15 studies, and one study used a mild alcohol group as reference [24]. Duration of follow-up ranged from 1 to 20.8 years, and sample size varied from 910 to 1,341,393 in the 16 studies.

Mortality

-

(1)

All-cause mortality

-

Of the two studies using drinking status as a criterion, one reported a significantly high risk only among women [25], and the other showed a significant effect on mortality in current drinkers compared with non-drinkers [26]. Two studies using frequency as a drinker classification criterion showed no significant results [1, 27]. In the five studies using amount of alcohol consumed, mild drinkers showed no significant mortality risk in two studies [24, 28], while three reported a significantly lower risk among men [29–31].

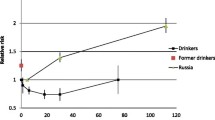

-

To analyze the risk of mild drinking, only five studies measuring the amount of alcohol consumed were included in the meta-analysis. The results of the meta-analysis did not show favorable effects of mild alcohol drinking on total mortality (OR: 0.85, 95 % CI: 0.72, 1.01) (Fig. 2).

-

-

(2)

Cancer-related mortality

-

Of eight studies in total, one study assessed drinking status and seven studies assessed alcohol amount. The study using drinking status showed non-significant results [32]. Of seven studies using alcohol amount for mild drinking classification, three reported significant results. Although Kimm et al. reported high mortality in mild drinkers [33], another two studies found lower mortality in mild drinkers compared with non-drinkers [24, 31].

-

Four reported the effects of alcohol consumption on all mortality from cancer [24, 31, 34, 35], and another four assessed the effect of alcohol on hepatocellular carcinoma [36], colorectal cancer [32], esophageal cancer [33], and digestive cancer [37]. Pooled results of mild drinking from four studies using all-cancer mortality showed beneficial effect (OR: 0.89, 95 % CI: 0.85, 0.94), however, it was not significant when adding three studies [33, 36, 37] assessing risk of mild drinking on specific type of cancer (OR: 1.02, 95 % CI: 0.90, 1.15) (Fig. 3).

-

-

(3)

Cardiovascular mortality

-

Three studies assessed the cardiovascular risk related to drinking alcohol. Although two studies using frequency and one study using alcohol amount as drinking criterion reported lower cardiovascular mortality in occasional or mild drinkers compared with non-drinkers [1, 28, 38], none of the results were statistically significant. Owing to the lack of studies, a meta-analysis of mild drinking as a risk factor for cardiovascular mortality could not be conducted.

-

Quality assessment and publication bias

Overall, the methodological quality of the included studies was moderate to high. Scores on the Newcastle-Ottawa scales were 4 to 5 points in case–control studies and 6 to 9 points in cohort studies. Exposed and non-exposed groups were in the same community in all studies, and most studies used structured interviews to ascertain exposure data. Additionally, all cohort studies used independent blind assessment or record linkages to assess outcomes. Based on the results of the quality assessment, none of studies was excluded from the meta-analysis.

The funnel plot did not present potential for publication bias (Fig. 4). Owing to the small number of studies for each outcome, a statistical test to evaluate publication bias could not be conducted.

Discussion

In recent meta-analyses, mild alcohol consumption showed a beneficial effect on all-cause mortality [6], cardiovascular mortality [7], and cancer-related mortality [8]. However, in this study mild drinking did not demonstrate a protective effect for all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality. Although mild alcohol consumption showed significant effect on all-cancer mortality, it was not significant on cancer-related mortality when adding various type of cancer. The difference in results could be caused by three factors: the criteria used to define mild drinking, the subjects, and the sample size.

First, the criterion of mild drinking is diverse. The previous meta-analyses of the relation between alcohol and cardiovascular and cancer-related mortality reported a beneficial effect from 2.5 to 14.9 g/day [7] and less than 12.5 g/day [8], respectively. The criterion used to define a mild amount of alcohol is inconsistent among studies included in this review. In the study by Jung et al., a weekly amount of less than 90 g was considered as mild drinking [24], while less than 70 g was used in the Yi et al. study [28]. Moreover, Kim et al. defined mild drinking as a daily amount of 30 g [31], whereas Jee et al. designated 25 g/day [36] and Lim and Park preferred 24 g/day [32]. Unjustified categorization of alcohol consumption might cause inaccurate results in individual studies, and different criteria for mild alcohol consumption between studies make it difficult to compare the results. To accurately assess the effect of alcohol consumption, a consensus on the alcohol intake considered to represent “mild drinking” should first be reached.

Second, the subjects included in this meta-analysis and those in previous ones differed. This review included only the Korean population. Besides biological factors including race, the effect of alcohol drinking could also differ based on behavioral factors [39]. While total alcohol per capita in Korea was higher, at 12.3 L of pure alcohol (men: 21, women: 3.9), compared with the world average of 6.2 L, the proportion of heavy episodic drinking was lower (6.0 %) than the world average (7.5 %) [40]. Not only the amount of alcohol and risky drinking, but also the type of beverage has an influence on the effect of alcohol on mortality. Although previous studies reported that wine and beer showed a greater protective effect than spirits on cardiovascular disease and cancer [41, 42], beer and wine accounted for only 26.6 % of total alcohol consumption in Korea [40]. Further studies assessing the effect of alcohol consumption should consider factors such as drinking patterns and beverage type.

Lastly, there is a possibility that the different results were due to the small number of studies. Whereas previous reviews included between 18 and 84 studies, the number of studies in this review was less than 10 for each outcome. Moreover, the studies including fewer than 10,000 subjects numbered 8 of the total 16 studies. To understand the reasons for these different results, more studies including Korean participants should be conducted to investigate the association between mild alcohol consumption and mortality risk.

Most of the included studies used non-drinkers as a reference group, but it is unclear whether they graded former drinkers as non-drinkers. Because some former drinkers quit drinking for health reasons, analyzing these subjects as non-drinkers could lead to biased results. Further misclassification, for example including occasional drinkers as non-drinkers or low-level drinkers, could bias risk estimates [43]. Appropriate classification of drinkers is important in assessing the risks of alcohol consumption.

In this review, several studies used different criteria for men and women [31, 37], while others applied the same criteria and analyzed both sexes together. In a previous meta-analysis investigating alcohol and total mortality, 2 to 4 drinks per day for men and 1 to 2 drinks per day for women were inversely associated with total mortality [6]. Women may be more vulnerable to alcohol-related risk, and men and women exhibit different drinking patterns [40]. Participants’ characteristics, such as sex, should be considered when assessing the impact of alcohol.

The age of the subjects in each study was diverse. Moreover, several studies chose subjects according to their residential area [28, 37] while others enrolled participants based on health examination [31]. Such variations might have contributed to population heterogeneity in this meta-analysis.

Previous studies have attributed the apparent benefits of alcohol to antioxidant capacity, anti-inflammatory effects, and the change in lipid profiles [41]. Rimm et al. reported that alcohol intake is causally related to a lower risk of coronary heart disease through changes in lipids and hemostatic factors [44]. Furthermore, another study revealed that alcohol has anti-inflammatory effects by reducing plasma fibrinogen and interleukin-1α levels [45]. However, high-dose ethanol increases mortality [6], and Carnevale and Nocella reported that long-term alcohol consumption involves increased oxidative stress and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules [46]. The biological mechanism of alcohol on health and mortality should be further assessed through additional studies.

Conclusions

This study did not provide evidence for the beneficial effects of mild drinking on all-cause, cancer-related, and cardiovascular mortality. Given the small number of studies included, larger prospective studies of the Korean population with more consistent criteria regarding mild drinking are needed.

References

Sull JW, Yi SW, Nam CM, Ohrr H. Binge drinking and mortality from all causes and cerebrovascular diseases in korean men and women: a Kangwha cohort study. Stroke. 2009;40:2953–8.

Park S, Kim SY, Hong JP. Cause-Specific Mortality of Psychiatric Inpatients and Outpatients in a General Hospital in Korea. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2012;27(2):164–75.

Bagnardi V, Zambon A, Quatto P, Corrao G. Flexible meta-regression functions for modeling aggregate dose–response data, with an application to alcohol and mortality. Am J Epidemio. 2004;159:1077–86.

Gmel G, Gutjahr E, Rehm J. How stable is the risk curve between alcohol and all-cause mortality and what factors influence the shape? A precision-weighted hierarchical meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. 2003;18:631–42.

White IR, Altmann DR, Nanchahal K. Alcohol consumption and mortality: modelling risks for men and women at different ages. BMJ. 2002;325:191.

Di Castelnuovo A, Costanzo S, Bagnardi V, Donati MB, Iacoviello L, de Gaetano G. Alcohol dosing and total mortality in men and women: an updated meta-analysis of 34 prospective studies. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2437–45.

Ronksley PE, Brien SE, Turner BJ, Mukamal KJ, Ghali WA. Association of alcohol consumption with selected cardiovascular disease outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011;342:d671.

** M, Cai S, Guo J, Zhu Y, Li M, Yu Y, et al. Alcohol drinking and all cancer mortality: a meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:807–16.

Rehm J, Greenfield T, Rogers J. Average volume of alcohol consumption, patterns of drinking, and all-cause mortality: results from the US National Alcohol Survey. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153:64–71.

Sun W, Schooling CM, Chan WM, Ho KS, Lam TH, Leung GM. Moderate alcohol use, health status, and mortality in a prospective Chinese elderly cohort. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19:396–403.

Higashiyama A, Okamura T, Watanabe M, Kokubo Y, Wakabayashi I, Okayama A, et al. Alcohol consumption and cardiovascular disease incidence in men with and without hypertension: the Suita study. Hypertens Res. 2013;36:58–64.

Mukamal KJ, Rimm EB. Alcohol consumption: risks and benefits. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2008;10:536–43.

Sempos CT, Rehm J, Wu T, Crespo CJ, Trevisan M. Average volume of alcohol consumption and all-cause mortality in African Americans: the NHEFS cohort. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:88–92.

Liu PM, Dosieah S, Zheng HS, Huang ZB, Lin YQ, Wang JF. Alcohol consumption and coronary heart disease in Eastern Asian men: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Zhonghua **n Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2010;38:1038–44.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Washington (DC): Dietary Guidelines for Americans; 2010.

Park S, Hong JP, Choi SH, Ahn MH. Clinical and laboratory predictors of all causes deaths and alcohol-attributable deaths among discharged alcohol-dependent patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37:270–5.

Min S, Noh S, Shin J, Ahn JS, Kim TH. Alcohol dependence, mortality, and chronic health conditions in a rural population in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2008;23:1–9.

Ryu M, Gombojav B, Nam CM, Lee Y, Han K. Modifying effects of resting heart rate on the association of binge drinking with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in older Korean men: the Kangwha Cohort Study. J Epidemio. 2014;24:274–80.

Jung SH, Gombojav B, Park EC, Nam CM, Ohrr H, Won JU. Population based study of the association between binge drinking and mortality from cancer of oropharynx and esophagus in Korean men: the Kangwha cohort study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:3675–9.

Sull JW, Yi SW, Nam CM, Choi K, Ohrr H. Binge drinking and hypertension on cardiovascular disease mortality in Korean men and women: a Kangwha cohort study. Stroke. 2010;41:2157–62.

Kim K. Trends of Alcohol Mortality in Korea: 1995–2000. Korean J Health Policy &Admin. 2004;14:24–43.

Yun JE, Won S, Kimm H, Jee SH. Effects of a combined lifestyle score on 10-year mortality in Korean men and women: a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:673.

Kim JY, Hwang JH, Choi JY, Cho DY, Yu BY. Risk factors influencing to mortality and recurrence after first cerebral infarction. J Korean Acad Fam Med. 2001;22:840–58.

Jung EJ, Shin A, Park SK, Ma SH, Cho IS, Park B, et al. Alcohol consumption and mortality in the Korean Multi-Center Cancer Cohort Study. J Prev Med Public Health. 2012;45:301–8.

Kim S, Lee S, Sohn S, Choi J. Association between health risk factors and mortality over initial 6 year period in Juam cohort. J Agri Med & Community. 2007;32:13–26.

Rhee CW, Kim JY, Park BJ, Li ZM, Ahn YO. Impact of individual and combined health behaviors on all causes of premature mortality among middle aged men in Korea: the Seoul Male Cohort Study. J Prev Med Public Health. 2012;45:14–20.

Park J, Koh S, Kim C, Kang M, Park K, Wang S, et al. What factors afffect mortality over the age of 40? Korean J Prev Med. 1999;32:383–94.

Yi S, Yoo S, Sull J, Ohrr H. Association between alcohol drinking and cardiovascular disease mortality and all-cause mortality - Kangwha cohort study-. J Prev Med Public Health. 2004;37:120–6.

Jeong HG, Kim TH, Lee JJ, Lee SB, Park JH, Huh Y, et al. Impact of alcohol use on mortality in the elderly: results from the Korean Longitudinal Study on Health and Aging. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;121:133–9.

Khang YH, Lynch JW, Yang S, Harper S, Yun SC, Jung-Choi K, et al. The contribution of material, psychosocial, and behavioral factors in explaining educational and occupational mortality inequalities in a nationally representative sample of South Koreans: relative and absolute perspectives. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:858–66.

Kim MK, Ko MJ, Han JT. Alcohol consumption and mortality from all-cause and cancers among 1.34 million Koreans: the results from the Korea national health insurance corporation’s health examinee cohort in 2000. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21:2295–302.

Lim H, Park B. Cohort study on the association between alcohol consumption and the risk of colorectal cancer in the Korean elderly. J Prev Med Public Health. 2008;41:23–9.

Kimm H, Kim S, Jee SH. The Independent Effects of Cigarette Smoking, Alcohol Consumption, and Serum Aspartate Aminotransferase on the Alanine Aminotransferase Ratio in Korean Men for the Risk for Esophageal Cancer. Yonsei Med J. 2010;51:310–7.

Lee S, Nam C, Yi S, Ohrr H. Cigarette smoking, alcohol and cancer mortality in men: the Kangwha cohort study. J Prev Med Public Health. 2002;35:123–8.

Park SM, Lim MK, Shin SA, Yun YH. Impact of prediagnosis smoking, alcohol, obesity, and insulin resistance on survival in male cancer patients: National Health Insurance Corporation Study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5017–24.

Jee SH, Ohrr H, Sull JW, Samet JM. Cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, hepatitis B, and risk for hepatocellular carcinoma in Korea. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1851–6.

Yi SW, Sull JW, Linton JA, Nam CM, Ohrr H. Alcohol consumption and digestive cancer mortality in Koreans: the Kangwha Cohort Study. J Epidemiol. 2010;20:204–11.

Meng K, Cho AJ, Kong SK. A case–control study on risk factors for the major cardiovascular deaths in Korean men: hypertensive disease and cerebrovascular disease. Ingu Pogon Nonjip. 1987;7:3–23.

Poli A, Marangoni F, Avogaro A, Barba G, Bellentani S, Bucci M, et al. Moderate alcohol use and health: A consensus document. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;23:487–504.

WHO. Global status report on alcohol and health. 2014.

Arranz S, Chiva-Blanch G, Valderas-Martinez P, Medina-Remon A, Lamuela-aventos RM, Estruch R. Wine, beer, alcohol and polyphenols on cardiovascular disease and cancer. Nutrients. 2012;4:759–81.

Chiva-Blanch G, Arranz S, Lamuela-Raventos RM, Estruch R. Effects of wine, alcohol and polyphenols on cardiovascular disease risk factors: evidences from human studies. Alcohol Alcohol. 2013;48:270–7.

Zeisser C, Stockwell TR, Chikritzhs T. Methodological biases in estimating the relationship between alcohol consumption and breast cancer: the role of drinker misclassification errors in meta-analytic results. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38:2297–306.

Rimm EB, Williams P, Fosher K, Criqui M, Stampfer M. Moderate alcohol intake and lower risk of coronary heart disease: meta-analysis of effects on lipids and haemostatic factors. BMJ. 1999;319:1523–8.

Estruch R, Sacanella E, Badia E, Antunez E, Nicolas JM, Fernandez-Sola J, et al. Different effects of red wine and gin consumption on inflammatory biomarkers of atherosclerosis: a prospective randomized crossover trial. Effects of wine on inflammatory markers. Atherosclerosis. 2004;175:117–23.

Carnevale R, Nocella C. Alcohol and cardiovascular disease: Still unresolved underlying mechanisms. Vascul Pharmacol. 2012;57:69–71.

Funding

This study was supported by the Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine (K15070).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JEP and SIC designed the study, and JEP and TYC conducted data search end analysis. JEP drafted the manuscript, YHR and SIC revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

PRISMA guideline. (DOC 64 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, JE., Choi, Ty., Ryu, Y. et al. The relationship between mild alcohol consumption and mortality in Koreans: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 15, 918 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2263-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2263-7