Abstract

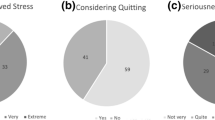

The domestic health care system has been facing a difficult task, especially in medical care, and Chinese nurses are under tremendous psychological pressure. Psychological support is a protective factor to relieve stress. This study examined the stress level and characteristics of Chinese nurses with different psychological support-seeking behaviours. Data from online questionnaires for this cross-sectional study were collected between January 2020 and February 2020 and yielded 2248 valid questionnaires for analysis with a response rate of 99.8%. General information of the respondents was also collected. The nurses’ stress levels were assessed using the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10). T tests, chi-square tests, and linear regression were used to examine the relationships among the factors. The results of this survey showed that between January and February 2020, 26.9% of nurses received psychological counselling, and the proportion was higher among men and nurses with lower education. The PSS-10 was related to gender, age group, provincial severity, and confidence in the control of the epidemic. The results showed that psychological support can effectively improve the confidence of domestic nurses in the face of arduous work and effectively relieve the psychological pressure caused by a heavy workload.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 2020, China and the world were facing a serious public health event, during which medical workers were engaged in the dual tasks of disease prevention and treatment [1]. Serious public health events lead to heavy workloads and mental burdens among nurses, and these negative impacts influence their work performance [2]. However, very few studies have unveiled the effects of the COVID pandemic with its repeated and ongoing stressors and traumatization among nurses.

Stress refers to a psychological state of tension that happens when an individual’s adaptive capacity does not meet the perceived environmental demands. Robbins’s stress model divides stressors into environmental, organizational, and personal factors that interact with individual differences to produce stressful experiences [3]. Compared with other occupations, nursing is considered to be a profession with a moderate stress level [2, 4]. Clinical registered nurses were the subjects of this study and were facing a greater than normal workload during a public health event outbreak. An increased workload and dangerous working environment can lead to negative emotions, increased psychological stress, and impaired physical health among nurses. These problems can prevent nurses from providing high-quality care, and their work efficiency can be greatly reduced. A study in China found that mental stress among nurses has increased while mental health has declined over the past 19 years, with work and family stress as the main stressors [31, 32]. The gender difference regarding dealing with stress may be related to negative interpersonal relationships, demanding jobs, a high degree of competition, gender discrimination, and biological differences [33,34,35,36,37,38].

The biological mechanisms of stress have been widely studied. In men, stress is associated with the right prefrontal cortex and the left orbitofrontal cortex, while in women, stress activates the limbic system. Studies have also indicated that there are sex differences in the core components of the HPA axis stress response. Serum corticosterone concentration and brain-derived neurotrophic factor methylation also show gender differences. Under controlled stress, it was found that 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) in men’ dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN) was effectively inhibited, while 5-HT in women’s DRN was not involved in behavioural control [39,40,41,42]. Thus, men tend to seek psychological intervention when they are aware that stress has influenced their mental status and work performance. In addition, controllable stress can protect against uncontrollable stress in the future, which explains why nurses who accessed psychological support experienced less stress and had a more positive co** attitude [37, 39,40,41,42,43,44,45].

Other common factors that influence stress

Our study found that age, professional title, and marital status affected the nurses’ stress level and stress perception; this finding is similar to previous research results.

The results of the mental health survey that Fan et al. (2019) administered to clinical nurses aged 20 to 49 showed that nurses under 30 years old experienced the greatest psychological stress, followed by nurses over 40 years old [46]. In contrast, Cohen et al. (2012) found that younger and older people were less stressed, while middle-aged people were more stressed [47].

In social and family life, the status, quality, and interaction of marital and professional titles symbolizing social status are closely related to stress. In general, nurses who hold supervisory positions experience the highest levels of work stress and the lowest levels of work satisfaction. Married nurses experienced lower levels of stress and physical discomfort and better social adjustment than unmarried nurses. Our results are in line with previous studies’ findings [38, 48,49,50].

Strengths and limitations

This study focused on the psychological stress and psychological support of nurses dealing with public events during the peak period of public health events in China. This study used a self-designed scale to measure the source of stress, which includes three factors: work, family, and society. In the future, we will expand the use of this questionnaire. This study had the following limitations: a) a convenience sampling method was employed, which might affect the generalizability of the conclusion. In the future, more rigorous sampling methods should be adopted to control the sampling deviation; b) other sources of stress might not be included, and more potentially influential stressors should be included in the future; and c) although this questionnaire has passed the reliability and validity tests, the use of this questionnaire is low at present; thus, further examination of the external validity of this questionnaire is needed.

Conclusion

During a public health event outbreak, nurses experienced high work, family, and social stress, among which gender, age, education level, the severity of public health incidents in the region, confidence in the authorities’ ability to control the epidemic, and psychological support were shown to be different. Psychological support has a benign regulatory effect on nurses, with the potential to improve their confidence and reduce stress. Therefore, it can be concluded that psychological support interventions for nurses during the epidemic is necessary and beneficial. Our findings suggest that society should pay attention to the mental health of nursing staff in addition to their physical health during public health events.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed in the current study are not publicly available due to the provisions of the policy document but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sogou S. National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China 2021; 2021.

Yang H, Lv J, Zhou X, Liu H, Mi B. Validation of work pressure and associated factors influencing hospital nurse turnover a cross-sectional investigation in Shaanxi Province, China. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):112.

Robbins. Organizational Behavior. Pearson Education, Inc; 1996.

Dincer B, Inangil D. The effect of emotional freedom techniques on nurses' stress, anxiety, and burnout levels during the COVID-19 pandemic: a randomized controlled trial. Explore (NY). 2021;2(17):109–14.

**n S, Jiang W, **n Z. Changes in Chinese nurses’ mental health during 1998-2016: a cross-temporal meta-analysis. Stress Health. 2019;35(5):665–74.

** M. Psychological stress of modern nurses and counter measures (in Chinese). Med Inf. 2015;28(51):254–5.

Khee KS, Lee LB, Chai OT, Loong CK, Ming CW, Kheng TH. The psychological impact of SARS on health care providers. Crit Care & Shock. 2004;2(7):99–106.

Lehmann, M., et al., Ebola and psychological stress of health care professionals. 2015.

Yang L, et al. MentaI HeaIth status of medical staffs fighting SARS: a long—dated investigation. Chin J Health Psychol. 2007;15(6):567–9.

Beauregard M. Mind does really matter: evidence from neuroimaging studies of emotional self-regulation, psychotherapy, and placebo effect. Prog Neurobiol. 2007;81(4):218–36.

**e Y. Psychological therapy: China Medical Science Press; 2006.

Jiao W. Positive effects of psychological capital: **’an Shiyou University; 2012.

Cui S, Zhang L, Yan H, Shi Q, Jiang Y, Wang Q, et al. Experiences and Psychhological adjustments of nurses who voluntarily supported COVID-19 patients in Hubei Province, China. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2020;13(3):1135–45.

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–96.

Ze P, Wang Z, Wang Y. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of perceived stress scale. J. Shanghai Jiaotong Univ. (Med. Sci.). 2015;35(10):1448–51.

Cohen S. Psychological stress and susceptibility to the common cold. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(9):606–12.

Cohen S. Psychological stress and susceptibility to upper respiratory infections. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152(4 Pt- 2):S53–8.

Fergusson DM. Impact of a major disaster on the mental health of a well-studied cohort. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(9):1025–31.

Qing H. Origin and function of stress-induced IL-6 in murine models. Cell. 2020;182(2):1660.

Iwata M. Psychological stress activates the Inflammasome via release of adenosine triphosphate and stimulation of the purinergic type 2X7 receptor. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80(1):12–22.

Vrshek-Schallhorn S. The cortisol reactivity threshold model: direction of trait rumination and cortisol reactivity association varies with stressor severity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2018;92:113–22.

Hodgson CI, et al. Perceived anxiety and plasma cortisol concentrations following rock climbing with differing safety rope protocols. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(7):531–5.

Armstrong AR, Galligan RF, Critchley CR. Emotional intelligence and psychological resilience to negative life events. Personal Individ Differ. 2011;51(3):331–6.

Goette L, et al. Stress pulls us apart: anxiety leads to differences in competitive confidence under stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;54:115–23.

Chmitorz A, et al. Intervention studies to foster resilience - a systematic review and proposal for a resilience framework in future intervention studies. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;59:78–100.

Liu D, et al. An investigation study on professional comprehensive competencies of graduates with different nursing educational levels. Chin J Nurs. 2003;06:27–9.

** J. On the Study Motivation of Faculty under the Stress of Academic Credentials --Case Study of Two Local Colleges: East China Normal University; 2010.

Xu J, Liu F. Influence of education level on nursing abilities of clinicial nurse. Chin Nurs Res. 2014;28(30):3741–2.

Yuru Zhang LLHW. A survey of the status of nurses ' professional psychological support and help attitude in the emergency department. Chin J Soc Med. 2021;6(38):656–60.

Wiegner L, et al. Prevalence of perceived stress and associations to symptoms of exhaustion, depression and anxiety in a working age population seeking primary care--an observational study. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:38.

Matud MP. Gender differences in stress and co** styles. Personal Individ Differ. 2004;37(7):1401–15.

Brougham RR, et al. Stress, sex differences, and co** strategies among college students. Curr Psychol. 2009;28(2):85–97.

Stroud LR, Salovey P, Epel ES. Sex differences in stress responses: social rejection versus achievement stress. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52(4):318–27.

Wang J, et al. Gender difference in neural response to psychological stress. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2007;2(3):227–39.

Dowler K, Arai B. Stress, gender and policing: the impact of perceived gender discrimination on symptoms of stress. Int J Police Sci Manag. 2008;10(2):123–35.

Herrero SG, et al. Influence of task demands on occupational stress: gender differences. J Saf Res. 2012;43(5–6):365–74.

Reschke-Hernmndez AE, et al. Sex and stress: men and women show different cortisol responses to psychological stress induced by the Trier social stress test and the Iowa singing social stress test. J Neurosci Res. 2017;95(1–2):106–14.

Cahlíková J, Cingl L, Levely I. How stress affects performance and competitiveness across gender. Manag Sci. 2020;66(8):3295–310.

Grahn RE, et al. Activation of serotonin-immunoreactive cells in the dorsal raphe nucleus in rats exposed to an uncontrollable stressor. Brain Res. 1999;826(1):35–43.

Maier SF, et al. Behavioral control, the medial prefrontal cortex, and resilience. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2006;8(4):397–406.

Maswood S, et al. Exposure to inescapable but not escapable shock increases extracellular levels of 5-HT in the dorsal raphe nucleus of the rat. Brain Res. 1998;783(1):115–20.

Rincón-Cortés M, et al. Stress: influence of sex, reproductive status and gender. Neurobiol Stress. 2019;10:100155.

Kudielka BM, Kirschbaum C. Sex differences in HPA axis responses to stress: a review. Biol Psychol. 2005;69(1):113–32.

Goel N, et al. Sex differences in the HPA axis. Compr Physiol. 2014;4(3):1121–55.

Niknazar S, et al. Comparison of the adulthood chronic stress effect on hippocampal BDNF signaling in male and female rats. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53(6):4026–33.

Fan Y, Li Y, Sun L. Correlation between TCM constitution,age and psychological stress of clinical health nurses. Chin Nurs Res. 2019;33(22):3969–70.

Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D. Who’s stressed? Distributions of psychological stress in the United States in probability samples from 1983, 2006, and 2009. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2012;42(6):1320–34.

Burman B, Margolin G. Analysis of the association between marital relationships and health problems: an interactional perspective. Psychol Bull. 1992;112(1):39–63.

Yuan M, et al. Study on effects of health status of Diferent marital status. Chin Arch Tradit Chin Med. 2011;29(7):1535–7.

Hu M, Pi H. Relation between nursing stress and job satisfaction in nurses with different professional titles. Acad J Pla Postgrad Med School. 2014;35(3):286–8.

Acknowledgements

We thank the units and friends who helped distribute this questionnaire.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81503475, 82004226), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2016A030313491), the Administration of Traditional Chinese and Tibetan Medicine of Qinghai Province (2016104), and the Science and Technology Project of Guangzhou Integrating Traditional Chinese Medicine and Western Medicine (20192A010014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Junrong Ye, Aixiang **ao and Lin Yu were responsible for the research design and manuscript preparation. Junrong Ye, Chen Wang, Chenxin Wu, Haoyun Wang, Ting Wang and Yuanxin Pan were responsible for the recruitment of respondents. Yufang Zhou and Shengwei Wu conducted the calculations and statistical analysis of the questionnaire results. Yufang Zhou, Junrong Ye, Youtian Wang, and Meilian Huang were involved in the drafting and editing of the manuscript. Lin Yu and Aixiang **ao performed critical revision of the paper for important intellectual content. All authors contributed to the paper, and all authors approved the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study obtained ethical approval from the IRB of the Affiliated Brain Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University (approval number: 2020–009). Informed consent was obtained from all participants before inclusion. The entire study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

There is nothing to disclose. There are no conflicts of interest for any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Medical staff respond to the investigation of the current situation of nCoV.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, Y., Wang, Y., Huang, M. et al. Psychological stress and psychological support of Chinese nurses during severe public health events. BMC Psychiatry 22, 800 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-04451-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-04451-8