Abstract

Background

Currently, there is no systematic review to investigate the effectiveness of digital interventions for healthy ageing and cognitive health of older adults. This study aimed to conduct a systematic review to evaluate the effectiveness of digital intervention studies for facilitating healthy ageing and cognitive health and further identify the considerations of its application to older adults.

Methods

A systematic review and meta-analysis of literature were conducted across CINAHL, Medline, ProQuest, Cochrane, Scopus, and PubMed databases following the PRISMA guideline. All included studies were appraised using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool Checklist by independent reviewers. Meta-analyses were performed using JBI SUMARI software to compare quantitative studies. Thematic analyses were used for qualitative studies and synthesised into the emerging themes.

Results

Thirteen studies were included. Quantitative results showed no statistically significant pooled effect between health knowledge and healthy behaviour (I2 =76, p=0.436, 95% CI [-0.32,0.74]), and between cardiovascular-related health risks and care dependency I2=0, p=0.426, 95% CI [0.90,1.29]). However, a statistically significant cognitive function preservation was found in older adults who had long-term use of laptop/cellphone devices and had engaged in the computer-based physical activity program (I2=0, p<0.001, 95% CI [0.01, 0.21]). Qualitative themes for the considerations of digital application to older adults were digital engagement, communication, independence, human connection, privacy, and cost.

Conclusions

Digital interventions used in older adults to facilitate healthy ageing were not always effective. Health knowledge improvement does not necessarily result in health risk reduction in that knowledge translation is key. Factors influencing knowledge translation (i.e., digital engagement, human coaching etc) were identified to determine the intervention effects. However, using digital devices appeared beneficial to maintain older adults’ cognitive functions in the longer term. Therefore, the review findings suggest that the expanded meaning of a person-centred concept (i.e., from social, environmental, and healthcare system aspects) should be pursued in future practice. Privacy and cost concerns of technologies need ongoing scrutiny from policy bodies. Future research looking into the respective health benefits can provide more understanding of the current digital intervention applied to older adults.

Study registration

PROSPERO record ID: CRD42023400707 https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=400707.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The number of people aged over 60 years is increasing worldwide [46]. Consequently, there is an increasing number of age-related diseases such as cardiovascular disease, depression, chronic pain, dementia, and cognitive decline [9, 46]. In Australia, healthcare costs for age-related diseases, specifically dementia-related care, are estimated to be over 3 billion of the total healthcare expenditure [2]. These costs are predicted to grow by 3.33% every year [12].

With the population ageing at an accelerated rate, healthy ageing has become a global healthcare agenda [44]. The main characteristic of healthy ageing is considered a person’s intrinsic mental and physical capacity, within their environment (e.g., social interaction), to function in everyday life [46]. To age successfully, a person’s health is defined not only by disease absence but also by optimising and maintaining the quality of everyday life [38].

Dementia is not an automatic consequence of ageing. However, dementia has a substantial relation to age-related diseases and causes significant disability and dependency among the older population [45]. As a neurocognitive disorder, dementia currently has no cure and there is limited evidence-based intervention proven effective in preventing the onset of dementia [24]. However, many health risks including obesity, physical inactivity, and unhealthy diet, are considered modifiable to mitigate age-related diseases. Thus, targeting age-related health risks to promote healthy ageing is seen as a preventative measure to reduce dementia risk development in the ageing population [46].

Digital technologies for older adults, anecdotally termed gerontechnology, have been utilised in many aspects of healthcare. They may appear in telehealth used in primary care or smartphone applications used to support mental (i.e., cognitive training) and physical health (i.e., exercise programs) [39]. However, currently, there is no systematic review investigating the effects of each available digital intervention applied to the older population. Therefore, this review aims to answer the following research questions:

-

1.

How effective are digital interventions to facilitate healthy ageing and cognitive health of older adults?

-

2.

What are the considerations of digital interventions to support healthy ageing and cognitive health for older adults?

Review design and methods

This review was conducted using a systematic review approach and guided by the Joanna Briggs Institute mixed-method systematic reviews [25]. The review was reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [32]. The review of quantitative studies allowed the study to evaluate the effectiveness of the digital interventions. Whereas the review of qualitative studies provides further understanding of the considerations influencing the digital intervention effects. The review protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42023400707).

Search strategy

Six databases were searched including CINAHL, Medline, ProQuest, Cochrane, Scopus, and PubMed. The main search terms were digital health, older people, and dementia. While there were limited results after three terms altogether, two terms were interchangeably searched, e.g., digital health AND older people, or digital health AND dementia. Detailed search terms are included in Supplementary Appendix 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This review included all types of intervention studies and used the Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome (PICO) framework to determine the eligibility of the study inclusion or exclusion.

Types of studies

This review included quantitative and qualitative studies that conducted an intervention using digital technologies to facilitate healthy ageing and maintain cognitive health of older adults including reducing the risk of cognitive decline or dementia in older adults. Randomised Controlled Trials (RCT) were included. Non-randomised controlled Trial studies included quasi-experimental, cohort, or quantitative components in the mixed method study. Qualitative studies included descriptive, explanatory, or ethnographic studies.

Population

This review included older adults with a mean age of greater than or equal to 55 years. Study populations primarily with dementia or cognitive impairment were excluded. However, studies were included if their intervention was primarily on healthy older adults but also included participants with mild cognitive impairment or dementia. This allowed the review to examine the intervention effects on slowing cognitive decline or reducing dementia risk for the purpose of maintaining/sustaining the cognitive health of older adults. This review focused on the up-to-date evidence-based data source. Only journal research articles that were published in the last 10 years and published in English were included.

Intervention

Studies that conducted an intervention using digital technology in older adults were included. Digital technology in this review was defined as any tool, device or resource that contains an electronic digital format. Studies that did not involve digital technology in the intervention or evaluation of the digital intervention were excluded.

Comparison

Studies using comparison or control groups in the intervention were included. The digital interventions without a comparison group were also included.

Outcome measure

The primary outcome of this review was the effect of digital intervention on promoting healthy ageing in older adults. Healthy ageing was considered in various areas relating to physical and mental health addressed in the study intervention for older adults. The secondary outcome was the effect of the digital intervention on maintaining the cognitive health of older adults. This included interventions aimed at slowing cognitive decline and reducing the risk of dementia to maintain the cognitive health of older adults. Cognitive functions were measured by the study using cognitive assessments such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR), global cognition z-score, Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) test, and Cardiovascular risk factors, Ageing and Incidence of Dementia (CAIDE). Digital interventions were grouped into categories based on the types of technology they used. The effects of the quantitative intervention outcomes were measured by statistical significance via the study-reported p-values. The effects of the qualitative intervention outcomes were measured by the study themes or the study-reported evaluation of user feedback.

Study selection and data extraction

To structure the study selection and data extraction process, the Preferred, Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) were followed [29]. Data synthesis was completed using Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia [10]. Titles and abstracts obtained from the search strategy were screened by two independent reviewers (YT and AP). Any disagreement on the study inclusion or exclusion was further assessed by the third reviewer (CG). All authors (YT, AP, JB, CG) independently reviewed the full-text articles based on the eligibility criteria and completed data extraction.

Quality assessment

Quality assessment of included studies was assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool Checklist (MMAT) [16]. The MMAT is a critical appraisal tool that allows the assessment of five study categories including qualitative, randomised control trials, non-randomised trials, and quantitative descriptive and mixed method studies. Each category set out five criteria for assessing the methodological quality and converting the assessment results into a score between 0 (low quality, high risk of bias) and 5 (high quality, low risk of bias). Each reviewer assessed the study quality independently and met to discuss the quality scores. Any discrepancy in the scores was further assessed by the third reviewer. A further level of evidence matrix using Stichler’s [41] method was applied to appraise the hierarchical quality of evidence with each study MMAT result. This level of evidence matrix allowed the review to weigh each study from level 1 indicating highly reliable evidence to level 6 indicating the least reliable evidence.

Data synthesis

The convergent integrated approach was applied to synthesise quantitative, qualitative and mixed-method studies [25]. The process occurred concurrently to combine extracted data from the studies.

Quantitative data

Wherever possible, quantitative studies with homogenous data were grouped to analyse their outcome measures reported in dichotomous or continuous data to synthesise the intervention effect for meta-analysis. The meta-analysis was done with the inverse variance analysis method and presented in forest plots as odd ratios for dichotomous data and standard mean differences for continuous data in JBI SUMARI software [31]. Heterogeneity between the studies was assessed by using I-squared (I2) tests where an I2 statistic value larger than 50% was considered substantial [14]. The overall effect of the studies was assessed by p-value where p ≤ 0.05 indicates statistically significant. Sensitivity analyses were performed by using a repeated measure to test the meta-analysis results. Where a meta-analysis was not possible, the quantitative data were synthesised with narrative descriptions.

Qualitative data

The data analysis was carried out using thematic analysis [8]. A mixture of inductive and deductive approaches was employed during the analysis process. Firstly, a complete reading of the results and conclusions was carried out with the different included studies. Secondly, information corresponding to the research questions of this review was identified, using the authors’ interpretations and textual quotes. The textual descriptions were then extracted directly from each qualitative study and assembled into several codes. Finally, main themes and sub-themes emerged and led to the main findings of this review. The entire process was developed by two reviewers (YT and JB) where the coding was initially done by one reviewer (JB) and checked by another reviewer (YT). The codes were then grouped and synthesised into emerging themes by one reviewer (YT) and reviewed by a third independent reviewer (AP).

Results

Study selection

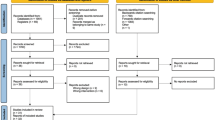

The database search yielded 2,909 articles. After applying limiters and removing duplicates, 1,991 articles were screened for title and abstract, and 29 were included for full-text screening. The eligibility of one study [43] appeared to be dissent between the reviewers due to the lack of a specific participant group outcome. Hence, the corresponding author of the article was contacted for further information. The study was included during the selection process, and the disagreement was resolved by all authors reaching a consensus on the quality assessment of the study. Sixteen studies were excluded from the 29 full-text screening. Of the 16 studies excluded, two studies were excluded because one was the phase one result of a research protocol, and another was the primary outcome from the study’s secondary analysis. The phase one results of a research protocol have the same results published in the research article that had been included in the review. The primary study of the secondary analysis was excluded because it was not related to the intervention or evaluation of the intervention. Another two studies were excluded because participants’ mean age was below 55. The rest of the twelve studies were excluded because they were not related to intervention or evaluation of intervention research. The final 13 studies were included in this review. Figure 1 summarises the study selection process adhering to the PRISMA guideline.

Preferred Reporting Item for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart for literature search [30]

Study characteristics and quality

Table 1 summarises the included study characteristics. Of thirteen studies included in this review (ntotal=19,551participants). Seven studies were quantitative research [6, 13, 17, 19, 22, 35, 43] (n=19,245 participants). Four studies were qualitative research, [3, 4, 18, 33] (n=260 participants). Two studies were mixed methods research [27, 42] (n=73 participants). Participants’ mean age ranged between 58 and 80 years. Three studies [3, 22, 43] (n=177) included both cognitively intact participants and participants with mild cognitive impairment, dementia, and cognitive decline. Only three studies specifically focused on improving the cognitive health of older adults [19, 22, 43] (n=13,651 participants), whereas two study interventions [17, 35] (n=2,871 participants) aimed to improve healthy ageing and cognitive health. For the meta-analysis of quantitative data, four quantitative studies presented dichotomous data [13, 19, 35, 43] and three quantitative studies presented continuous data [6, 17, 22].

The study appraisal using the MMAT is detailed in Table 1. Study quality assessments from the MMAT scores were between 3 and 5 indicating moderate to high study quality, with a low to moderate risk of bias. Table 2 shows the level of evidence matrix with MMAT score. The evidence matrix of each included study falls between levels 2 and 3, indicating a moderate to high level of study evidence [41].

All studies used digital technology to facilitate healthy ageing or maintain the cognition of older adults. Ten studies focused on healthy ageing in various health areas, including health literacy, self-health management, physical activity, social isolation, care dependency, health service communication, and assistive home living. Three studies focused on maintaining the cognitive health of older adults, including sustaining cognitive function by utilising technology to slow further cognitive decline or reduce the risk for dementia [19, 22, 43]. Two studies addressed their interventions for both healthy ageing and cognitive health of older adults [17, 35].

Type of digital intervention

The commonly used digital technology for older adults in the reviewed studies were information, assistive and communication types of technology. Seven studies implemented information type of technology (i.e., website program, digital learning platform) to deliver educational content influencing older adult’s knowledge, awareness, lifestyle, physical activities, and cognition [6, 13, 17, 22, 33, 35, 43]. Five studies incorporated an assistive type of technology (i.e., computer, mobile application, smart home device) to support the well-being of people with health conditions, reduce health risks and physical inactivity of older adults and observe the impact of the technology on persons’ cognitive function over time [3, 18, 19, 27, 35]. Three studies utilised communication technology (i.e., video calls and social media platforms) to reduce social isolation, language decline of older migrants, care dependency and health service communication [4, 13, 42]. Three studies appeared to include hybrid-type technology, including both assistive and communication types [18], communication and information types [13] or assistive and information types [35]. Figure 2 summarises types of digital technology and the targeted health areas.

Effectiveness of digital intervention for healthy ageing and cognitive health

Studies that use digital technology to facilitate healthy ageing in older adults can be summarised into the improved health knowledge and increased physical activities but had no change in health risk reduction and care independence. Studies that use digital technology for cognitive health found it to maintain the cognitive function of older adults when using digital devices (e.g., laptops or cellphones) or engaging in computer-based physical activities in the longer term. There were also improved dementia risk scores from cardiovascular risk reduction and improved depression, anxiety and the associated risks for dementia from the digital programs. The following sections synthesise the review findings from the quantitative and mixed-method studies and meta-analysis.

Health knowledge for healthy behaviour

Online training programs and digital learning platforms were utilised to promote health knowledge, healthy behaviour, digital literacy and competency [6, 17]. Compared to the conventional method of content delivery (face-to-face), older adults in the digital format group had increased ability in health information search (p<0.01), knowledge of nutrition status (p<0.05) and adaptation to ageing (p<0.05) [17]. Digital health literacy examined by the eHealth literacy scale in Bevilacqua et al. [6] also showed a statistically significant improvement in participants’ health knowledge after the digital training program (p=0.001). However, the overall satisfaction with Bevilacqua et al. [6] online training program was not statistically significant (p=0.107). The increased knowledge to health behaviour and mental health were not statistically significant in Hsu et al. [17] digital program. The pooled effect of these two digital programs [6, 17]on health knowledge to healthy behaviour showed not statistically significant (I2 =76, p=0.436, 95% CI [-0.32,0.74]) (see Fig. 3).

Physical activities and health risk reduction

Digital devices were incorporated into online training programs to increase older adults’ physical activity and reduce cardiovascular-related health risks and the risk of care dependency [13, 17, 27, 35]. A wearable tracker with a smartphone application increased older adults’ engagement in their daily physical activities [27]. However, the digital education program to improve regular exercise by Hsu et al. [17] did not show statistically significant (p=0.084). For health risk reduction, older adults in the coach-supported internet platforms had no statistically significant effect on cardiovascular risk (p=0.10) and lifestyle change to physical activity was also not statistically significant (p=0.34) [35]. The progression in long-term care grade indicating a risk of care dependency of older adults was not statistically significant after the multi-component care approach [13]. The pooled effect of the two studies [13, 35] on reducing cardiovascular-related health risks and care dependency was not statistically significant (I2=0, p=0.426, 95% CI [0.90,1.29]) (see Fig. 4).

Cognitive health

Digital technology has been utilised to maintain the cognitive health of older adults including slowing cognitive decline and reducing the risk of dementia development [17, 19, 22, 35, 43]. The longitudinal cohort study that observed participants over 8 years using cellphones and desktop devices showed some degree of influence on people’s cognitive functions [19]. The effect of both devices was not statistically different in the 2-year follow-up (p=0.30) but different statistically significant in the 4-year follow-up (p<0.01) [19]. The study also found different cognition effects between using a cellphone device alone or combined with desktop computer users (p<0.01) [19]. In a computer-based digital inclusion with a physical activity program, older adults had an increased score in the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) (p<0.001) and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (p=0.022) over the 4-month follow-up [43]. However, participants with mild cognitive impairment (Clinical Dementia rating (CDR): 0.5) (n=51) showed no statistically significant change (p=0.600) [43]. The pooled effect of these two digital interventions [19, 43] on older adults’ cognitive health showed a statistically significant improvement (I2=0, p<0.001, 95% CI [0.01, 0.21]) (see Fig. 5).

Other cognitive health studies have shown various outcomes [17, 22, 35]. A virtual cognitive health program did not show a statistical difference in cognition scores at a 24-week follow-up when measured by Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status scores (RBANS) (p=0.15). However, a statistically significant increase in participant cognition was reported at 52 weeks (p<0.01) [22]. The secondary effect of the program on older adult’s depression, anxiety and risk of develo** dementia also differed statistically significantly from baseline to week 52 (p<0.01) [22]. In Richard et al. [35], older adults' dementia risk scores from the Cardiovascular risk factors, Ageing and Incidence of Dementia (CAIDE) showed a statistically significant improvement after the coach-supported internet platform intervention (p=0.02). Cognitive health improved in Hsu et al. [17] following digital program intervention, however, it was not statistically significant (p=0.132). The variation of the intervention outcomes showed between different timeframes. The pooled effect of these three studies [17, 22, 35] on older adults’ cognitive health was not statistically significant (I2=99, p=0.7, 95% CI [-2.27, 1.52]) (see Fig. 6).

Considerations of the digital application to older adults

Thematic analysis was conducted from the qualitative and mixed-method studies and is shown in Table 3. The following sections summarise the emerging themes of digital engagement, communication, independence, human connection, privacy, and cost.

Digital engagement

Digital engagement in this review refers to the extent to which older adults adhere to or interact with digital intervention. Digital literacy/competency, age, motivation and person-centred were identified to influence digital engagement in older adults [18, 27, 33, 42]. Older age has been viewed as a barrier to the extent of a person’s digital device usage [18, 42]. A generational gap in technology use was found in people aged 80 or older with lower or absent use of digital devices compared to those aged 65 and 79 [18]. Older adults were also less confident in their ability to use the digital tool without any assistance [42]. However, individual preferences and choices of person-centred manner drove positive digital engagement [18]. The flexibility of the programs motivated participants to exercise in their own time [33]. Whereas some participants found it difficult to follow with a lack of clear structure [33].

Communication and Independence

Health service communication and the importance of independent living were addressed among older adults [3, 18, 42]. A digital health module that was equipped with a video conferencing feature has enabled older migrants with cancer to communicate with their healthcare providers [42]. Assisted by a smartphone care coordination application, older adults perceived it useful in facilitating communication between patients, family caregivers, and physicians [18]. Additionally, installing a voice control tablet at home for older adults with health conditions enabled them to obtain information and organise personal appointments and medications, positively impacting their independence and reducing stress on carers [3].

Human connection

Social isolation and companionship related to human connection were mentioned among older adults [4, 18]. Using video calls or social media platforms, older adults with migration backgrounds could stay connected and maintain their own social and cultural identities [4]. However, older adults expressed fear of reducing human contact with increased technology use [18]. The robotic devices for companionship were found to infantilise general older adults and deceive people living with dementia [18].

Privacy and cost

Issues were also raised regarding privacy, safety, and the cost of the technology [6, 18, 33]. Collecting personal information in the digital application could be repurposed, leaked, or accessed by a third party [18]. Health insurance does not cover reimbursement of digital health technologies which may result in socioeconomic inequalities and low adoption of digital health technologies [18]. The cost concern of technology was found to impact participants’ satisfaction with the training program significantly [6].

Discussion

This review investigated the effectiveness of digital interventions to facilitate healthy ageing and cognitive health and further identified the considerations of its application to older adults. Information, assistive and communication technology were the commonly used types of intervention for older adults. Whilst the study interventions on facilitating healthy ageing were not statistically significant, positive effects were found in the cognitive functions of older adults. The following two sections discuss the effectiveness of the reviewed interventions and considerations of their application to older adults.

The effectiveness of digital health interventions to facilitate healthy aging and cognitive health in older adults

Digital interventions used in older adults to facilitate healthy ageing were not always effective. The main areas for facilitating healthy ageing from the reviewed studies were summarised into health knowledge, healthy behaviours, physical activities, health risk reduction and care dependency. Health knowledge of the older participants was improved in most digital programs [6, 13, 17, 33, 35]. However, despite the health knowledge was increased among the older participants, the overall health effects on healthy ageing, and health risk reduction were not statistically significant in the meta-analysis [6, 13, 17, 35]. The discrepancy between the individuals’ health knowledge and the health behaviour/implementation is relevant to a study suggesting that health outcomes are not only determined by scientific knowledge improvements but encompass a deeper understanding of one’s perception, choice, and the perceived meaning of a healthy lifestyle [11]. Thus, improving the health knowledge/literacy of individuals does not necessarily result in healthy behaviours and health risk reduction in the older population.

Despite no significant health changes from the improved health knowledge, some older groups were found to particularly benefit from digital interventions, such as carers, immigrants, and people with language barriers. Consistent with the literature, examples were voice-control devices that assist people with chronic diseases and dementia to maintain independent living and reduce carers’ burden [3, 26, 39]. Using social media platforms was found to increase social connection among older immigrants [4]. Health consultation and medical assessment through digitalised care systems created more personalised communication to reduce language barriers and increase social inclusion and health equality for people with non-native-speaking backgrounds [20, 42, 21].

Further, the time taken to see the cognition effect from digital devices/interventions seems longer. The average time to see a statistically significant difference in cognitive functions was greater than 4 years [19, 22]. The interventions that were implemented in less than a 2-year timeframe did not have statistically significant effects on individuals’ cognitive functions [19, 43]. This finding was congruent with the fact that both prevention and intervention for cognitive decline in ageing often require a length of time to capture the effects on each individual [34]. This suggests that long-term enhancement and methodological measurement of digital devices are needed for the cognitive health of older adults. Moreover, compared to the non-digital device users, there was a moderately better but not statistically significant cognitive performance of older participants exposed to digital devices and interventions [17], 22, 35. This enhances the daily use of digital devices that may maintain cognitive health for older adults.

Moreover, loss of human contact remains a major concern for older adults, particularly robotic devices replacing conventional human-to-human interaction [18, 40]. The review found that the intervention containing human coaching had more positive outcomes in the studied health areas compared to the interventions without [3, 18, 35]. This suggests that incorporating human factors into digital intervention is needed for older adults [7]. Furthermore, some digital devices require skilled personnel and the relevant health funds are not always available to older adults [18, 42]. This suggests that accessibility and affordability of digital devices require public health initiatives to work in partnership with older adults to strengthen the assessment of individual needs and associated costs.

Recommendations and implications for practice, policy, and future research

Practice

Although individuals’ health knowledge does not necessarily lead to changes in health behaviours, the potential benefits from the overall health knowledge improvements are still acknowledged and should continue being the efforts in future approaches and practices. Indeed, with technologies changing over time, older adults will need to continue learning and practising new skills to bring a more positive impact on own health. Therefore, digital interventions that are designed to facilitate learning and knowledge translation for older adults are inevitably valuable. Moreover, digital engagement emerged as a driving force in knowledge translation and determining whether digital intervention on older adults comes into effect. Digital competency, age, motivation, and meeting individual needs (a person-centred approach) were factors influencing individuals’ digital engagement. Human-to-human interaction (human coaching) was also considered crucial. In essence, meeting individual needs may not sufficiently address the complexity of the health needs of older adults. The expanded meaning of a person-centred concept in older adults (look beyond a person’s health needs from social (i.e., social connection/network impacts), environmental (i.e., health/funding resources) and healthcare systems (i.e., care distribution/equality/communication)) should be pursued. Therefore, future practice is needed to address the factors with a broader person-centred concept to assist older adults with knowledge translation and health implementation.

Policy

The concerns of privacy, safety and cost in technology are not new. On the broader level of policy and decision-making, personal data security and a safe digital environment must be protected by government regulations with a standard reviewing process to catch fast-changing technologies. The national standards for digital devices and healthcare systems should be regularly assessed and monitored by policy bodies. In addition, the price value and total cost of technologies need to be supported by healthcare initiatives and funding resources to ensure equality and affordability are maintained for the growing ageing population.

Research

Several areas from the reviewed interventions can be further explored and pursued in future research. Firstly, person-centred has been viewed as an important concept when designing digital interventions for older adults. Although the concept seemed to have been integrated into most reviewed studies, the challenge today is how older individuals benefit from the learned knowledge to reduce their health risks. This may mean the investigation into the specific health benefits of digital intervention, for example, by reducing risks in cardiovascular diseases (i.e., hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, stroke), musculoskeletal symptoms (i.e., chronic pain, physical mobility), or mental health conditions (i.e., depression, anxiety). Therefore, future research looking into the specific health benefits would gain a better understanding of the digital phenomenon in older adults.

Secondly, human connection and communication between patients and healthcare providers are important areas of maintaining individual health and independent living. The population ageing and the rising number of older immigrants in most developed countries strongly impact healthcare usage [15, 28]. This implies a need for addressing healthcare inclusion for older immigrants. Thirdly, long-term use of digital devices seems to benefit cognitive health. However, it is unclear whether technology can impact specific cognitive domains. The domain areas of complex attention, executive function, learning and memory, language, perceptual-motor control and social cognition are related to the development of dementia [1]. As the causes of develo** dementia are still uncertain to our current knowledge, future research that investigates specific impacts on a cognitive domain from technology applications may provide more understanding about the digital ways of maintaining brain health for older adults.

Limitations

This review has several limitations in terms of the search strategy and study comparison. As digital health is a broad area, the review limited the search on the topic to only use the keywords search and did not employ mesh terms or expanded words. This has limited the search strategy and may have missed the studies that ought to be included. Cognitive health, the secondary outcome of this review, is also a large topic, therefore this review only included a pragmatic selection of cognitive function measures addressed in the reviewed studies. Moreover, this review primarily focused on healthy older adults and excluded the studies that focused on people with dementia and cognitive impairment. Many intervention studies that focused on dementia and cognitive impairment were also excluded. This narrowed scope has limited the included studies in comparison to dementia risk reduction. Furthermore, the heterogeneous nature of the mixed-method studies limited the comparison of each study intervention.

Conclusions

The evolution of digital technologies has accelerated its influence on the everyday life of older adults and healthcare. This review evaluated the effectiveness of digital interventions for healthy ageing and cognitive health of older adults through a systematic approach and meta-analysis. Health interventions using digital technology to facilitate healthy ageing of older adults were not always effective. Therefore, knowledge translation into everyday health behaviour to reduce risks is key to effective digital intervention. The overall cognitive functions of older participants were improved by digital interventions; however, it often requires a longer intervention period. Each intervention effect and considerations identified give rise to the areas for future practice, policy, and research. Indeed, technologies will continue to advance, and the perspectives and experiences of older adults on digital approaches to their health may differ from time to time and from generation to generation [36]. Therefore, future work involving digital technology for older adults is necessary to reflect on the intervention effects and considerations identified in this review. Ensuring healthcare innovations can be practically implemented into the everyday life of older adults.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Reference

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2022). Dementia in Australia Australian government Retrieved 16/12 from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/dementia/dementia-in-aus/contents/health-and-aged-care-expenditure-on-dementia.

Balasubramanian GV, Beaney P, Chambers R. Digital personal assistants are smart ways for assistive technology to aid the health and wellbeing of patients and carers. BMC Geriatrics. 2021;21(1):643. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02436-y.

Baldassar L, Wilding R, Bowers BJ. Migration, aging, and digital kinning: the role of distant care support networks in experiences of aging well. Gerontologist. 2020;60(2):313–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnz156.

Bell I, Pot-Kolder RMCA, Wood SJ, Nelson B, Acevedo N, Stainton A, Nicol K, Kean J, Bryce S, Bartholomeusz CF, Watson A, Schwartz O, Daglas-Georgiou R, Walton CC, Martin D, Simmons M, Zbukvic I, Thompson A, Nicholas J, Allott K. Digital technology for addressing cognitive impairment in recent-onset psychosis: a perspective. Schizophr Res. 2022;28:100247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scog.2022.100247.

Bevilacqua R, Strano S, Di Mirko R, Giammarchi C, Katerina Katka C, Mueller C, Maranesi E. eHealth literacy: from theory to clinical application for digital health improvement. results from the ACCESS training experience. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(22):11800. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211800.

Bradwell HL, Edwards KJ, Winnington R, Thill S, Jones RB. Companion robots for older people: importance of user-centred design demonstrated through observations and focus groups comparing preferences of older people and roboticists in south West England. BMJ Open. 2019;9(9):e032468. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032468.

Braun V, Clarke V, Hayfield N, Terry G. Thematic Analysis. In: Liamputtong P, editor. Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences. Singapore: Springer; 2019. p. 843–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_103.

Coley N, Andre L, Hoevenaar-Blom MP, Ngandu T, Beishuizen C, Barbera M, van Wanrooij L, Kivipelto M, Soininen H, van Gool W, Brayne C, Moll van Charante E, Richard E, Andrieu S. Factors predicting engagement of older adults with a coach-supported eHealth intervention promoting lifestyle change and associations between engagement and changes in cardiovascular and dementia risk: secondary analysis of an 18-month multinational randomized controlled trial. J Med Int Res. 2022;24(5):e32006. https://doi.org/10.2196/32006.

Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org.

Gillsjö C, Karlsson S, Ståhl F, Eriksson I. Lifestyle’s influence on community-dwelling older adults’ health: a mixed-methods study design. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2021;21:100687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conctc.2020.100687.

Harris A, Sharma A. Estimating the future health and aged care expenditure in Australia with changes in morbidity. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0201697. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201697.

Hasemann L, Lampe D, Nebling T, Thiem U, von Renteln-Kruse W, Greiner W. Effectiveness of a multi-component community-based care approach for older people at risk of care dependency - results of a prospective quasi-experimental study. BMC Geriatrics. 2022;22(1):Article 348. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-02923-w.

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savović J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JA. The Cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928.

Holecki T, Rogalska A, Sobczyk K, Woźniak-Holecka J, Romaniuk P. Global elderly migrations and their impact on health care systems [perspective]. Front Public Health. 2020;8:386. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00386.

Hong QN, Pluye P, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018. Registration of Copyright (#1148552), Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada; 2018.

Hsu H-C, Kuo T, Ju-** L, Wei-Chung H, Chia-Wen Y, Yen-Cheng C, Wan-Zhen X, Wei-Chiang H, Ya-Lan H, Mu-Ting Y. A cross-disciplinary successful aging intervention and evaluation: comparison of person-to-person and digital-assisted approaches. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(5):913. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15050913.

Ienca M, Schneble C, Kressig RW, Wangmo T. Digital health interventions for healthy ageing: a qualitative user evaluation and ethical assessment. BMC Geriatrics. 2021;21(1):412. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02338-z.

** Y, **g M, Ma X. Effects of digital device ownership on cognitive decline in a middle-aged and elderly population: longitudinal observational study. J Med Intern Res. 2019;21(7):e14210. https://doi.org/10.2196/14210.

Kemp E, Trigg J, Beatty L, Christensen C, Dhillon HM, Maeder A, Williams PAH, Koczwara B, Elmer S. Health literacy, digital health literacy and the implementation of digital health technologies in cancer care: the need for a strategic approach. Health Prom J Aust. 2021;32:104–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpja.387.

Kim H, Kelly S, Lafortune L, Brayne C. A sco** review of the conceptual differentiation of technology for healthy aging. Gerontologist. 2021;61(7):e345–69. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaa051.

Kumar S, Tran J, Moseson H, Tai C, Glenn JM, Madero EN, Krebs C, Bott N, Juusola JL. The impact of the virtual cognitive health program on the cognition and mental health of older adults: pre-post 12-month pilot study. JMIR Aging. 2018;1(2): e12031. https://doi.org/10.2196/12031.

Levine DM, Lipsitz SR, Linder JA. Changes in everyday and digital health technology use among seniors in declining health. J Gerontol. 2017;73(4):552–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glx116.

Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda SG, Huntley J, Ames D, Ballard C, Banerjee S, Burns A, Cohen-Mansfield J, Cooper C, Fox N, Gitlin LN, Howard R, Kales HC, Larson EB, Ritchie K, Rockwood K, Sampson EL, Mukadam N. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017;390(10113):2673–734. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6.

Lizarondo, L., Stern C, Carrier J, Godfrey C, Rieger K, Salmond S, Apostolo J, Kirkpatrick P, H., L. (2020). Chapter 8: Mixed methods systematic reviews. In M. Z. Aromataris E (Ed.), JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-09.

Madara M, Keshini,. Assistive technologies in reducing caregiver burden among informal caregivers of older adults: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2016;11(5):353–60. https://doi.org/10.3109/17483107.2015.1087061.

Mair JL, Hayes LD, Campbell AK, Buchan DS, Easton C, Sculthorpe N. A personalized smartphone-delivered just-in-time adaptive intervention (JitaBug) to increase physical activity in older adults: mixed methods feasibility study. JMIR Formative Research. 2022;6(4):Article e34662. https://doi.org/10.2196/34662.

Mir UR, Hassan SM, Qadri MM. Understanding globalization and its future: an analysis. Pak J Soc Sci. 2014;34(2):607–24.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8(5):336–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The Prisma Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Munn Z, Aromataris E, Tufanaru C, Stern C, Porritt K, Farrow J, Lockwood C, Stephenson M, Moola S, Lizarondo L, McArthur A. The development of software to support multiple systematic review types: the JBI System for the Unified Management, Assessment and Review of Information (JBI SUMARI). Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2018.

Page, M., McKenzie, J., Bossuyt, P., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T., Mulrow, C. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372(71). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

Pettersson B, Wiklund M, Janols R, Lindgren H, Lundin-Olsson L, Skelton DA, Sandlund M. “Managing pieces of a personal puzzle” - older people’s experiences of self-management falls prevention exercise guided by a digital program or a booklet. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):43. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1063-9.

Richard E, Jongstra S, Soininen H, Brayne C, Moll van Charante EP, Meiller Y, van der Groep B, Beishuizen CRL, Mangialasche F, Barbera M, Ngandu T, Coley N, Guillemont J, Savy S, Dijkgraaf MGW, Peters RJG, van Gool WA, Kivipelto M, Andrieu S. Healthy ageing through internet counselling in the elderly: the HATICE randomised controlled trial for the prevention of cardiovascular disease and cognitive impairment. BMJ Open. 2016;6(6):e010806. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010806.

Richard E, Moll van Charante EP, Hoevenaar-Blom MP, Coley N, Barbera M, van der Groep A, Meiller Y, Mangialasche F, Beishuizen CB, Jongstra S, van Middelaar T, Van Wanrooij LL, Ngandu T, Guillemont J, Andrieu S, Brayne C, Kivipelto M, Soininen H, Van Gool WA. Healthy ageing through internet counselling in the elderly (HATICE): a multinational, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Digital Health. 2019;1(8):e424–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2589-7500(19)30153-0.

Rogers WA, Fisk AD. Toward a psychological science of advanced technology design for older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2010;65(6):645–53. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbq065.

Röhr S, Kivipelto M, Mangialasche F, Ngandu T, Riedel-Heller SG. Multidomain interventions for risk reduction and prevention of cognitive decline and dementia: current developments. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2022;35(4):285–92. https://doi.org/10.1097/yco.0000000000000792.

Rudnicka E, Napierała P, Podfigurna A, Męczekalski B, Smolarczyk R, Grymowicz M. The World Health Organization (WHO) approach to healthy ageing. Maturitas. 2020;139:6–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.05.018.

Santini S, Galassi F, Kropf J, Stara V. A digital coach promoting healthy aging among older adults in transition to retirement: results from a qualitative study in Italy. Sustainability. 2020;12(18):7400. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187400.

Simon, C., Waycott, J. (2022). Can robots really be companions for older adults? University of Melbourne Retrieved 12/04 from https://pursuit.unimelb.edu.au/articles/can-robots-really-be-companions-for-older-adults.

Stichler JF. Weighing the Evidence. HERD Health Environ Res Des J. 2010;3(4):3–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/193758671000300401.

Sungur H, Yılmaz NG, Chan BMC, van den Muijsenbergh METC, van Weert JCM, Schouten BC. Development and evaluation of a digital intervention for fulfilling the needs of older migrant patients with cancer: user-centered design approach. J Med Int Res. 2020;22(10):e21238. https://doi.org/10.2196/21238.

Vicentin AP, Simões EJ, Bonilha AC, Lamoth C, Andreoni S, Ramos LR. Effects of combined digital inclusion and physical activity intervention on the cognition of older adults in Brazil. Gerontechnology. 2020;19(3):1–10. https://doi.org/10.4017/gt.2020.19.003.10.

World Health Organisation. (2022). Dementia WHO. Retrieved 16/12 from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia#:~:text=Studies%20show%20that%20people%20can,cholesterol%20and%20blood%20sugar%20levels.

World Health Organization. (2019). Dementia. WHO. Retrieved 18/09 from https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia.

World Health Organization. (2023). Ageing and health. World health organization. Retrieved 14/12 from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health.

**e B, Charness N, Fingerman K, Kaye J, Kim MT, Khurshid A. When going digital becomes a necessity: ensuring older adults’ needs for information, services, and social inclusion during COVID-19. J Aging Soc Policy. 2020;32(4–5):460–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2020.1771237.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

None reported.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YT searched the database, designed, reviewed study inclusion/exclusion, quality assessment, analysed, interpreted, drafted, and wrote the article. JB reviewed study inclusion/exclusion, quality assessment, and analysed the included qualitative studies. CG reviewed study inclusion/exclusion, quality assessment, edited the article. AP reviewed study inclusion/exclusion, quality assessment, interpreted and edited the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tsai, Y.IP., Beh, J., Ganderton, C. et al. Digital interventions for healthy ageing and cognitive health in older adults: a systematic review of mixed method studies and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr 24, 217 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04617-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04617-3