Abstract

Dynamic characteristic significantly affects performance of RV reducer. The current researches mainly pay attention to free vibration properties of RV reducer. In order to satisfy the increasing demand on high performance, response sensitivity is analytically studied on the basis of cyclic symmetry structure. Based on the structure characteristics, a dynamic model is developed by taking into account the influence of bearing stiffness, crankshaft bending stiffness and mesh stiffness within planetary and cycloidal stages. For the model, governing equation of motion is derived and solved by Fourier series method. The solution revealed that forced vibrations at primary frequency are well defined structural. There exist three typical forced vibration modes: rotational, translational and planetary component modes. Response sensitivity to basic design parameters is obtained as closed-form expressions by differential method. With the typical vibration modes, response sensitivity is simplified and classified into three types. Calculation of sensitivity implies that vibrations of the output wheel are sensitive to eccentricity. As eccentricity increases, sensitivity of translation decreases first and then increases, but sensitivity of rotation always increases. The proposed method for analyzing response sensitivity provides some principles for selecting parameters for RV reducer from the point of view of forced vibration.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

RV reducer is widely used in industrial robots due to the advantages such as compact structure, multi-teeth meshing and high carrying capacity, large transmission ratio and high transmission efficiency. However, vibration significantly affects the positioning and repeatability, especially for high performance applications, such as semiconductor manufacturing and space industry.

RV reducer is a newly developed reducer on the basis of cycloid gear. Although the vibration of spur gear has studied by many researchers, the vibration of cycloid gear has received little attention. Refs. [1, 2] develop dynamic model of a single stage cycloid drive. Zhang et al. [3, 4] formulated a dynamic model of RV reducer which considered mesh and bearing stiffness. Thube et al. [5] established finite element model of cycloid speed reducer and analyzed the load and stress distributions. Hsieh [6] developed mathematical model for the dynamic analysis of cycloid speed reducer. These studies have laid a foundation for the construction of dynamic model of RV reducer.

Known from literatures above, scholars mainly pay attention to free vibration properties. Although wide study has been carried out in the analysis of mechanical transmission [7], research about dynamic response and parameter selection of RV reducer is scare. Parameter sensitivity analysis provides an effective method for dynamic analysis and parameter selection. Because of this, researchers addressed the parameter sensitivity to modal behaviors of the planetary gears [8, 9]. Zhu et al. [10] researched the effects of pin stiffness on natural frequencies. Zhang et al. [3, 4] numerically studied the sensitivity of the crankshaft bending stiffness and bearings support stiffness to natural frequencies of RV reducer. The above studies normally employ numerical calculations. To achieve more finds, Refs. [11,12,13,14,15,16] analytically examine the modal sensitivity based on typical free vibration modes of planetary gears. These studies provide valuable insights into sensitivity calculation of free vibration.

While sensitivity of free vibration can provide information for parameters selection, sensitivity of forced vibration can aid the selection in a more straight way. However, there is little literature on this respect, especially for RV reducer. Related research was generally carried out by using numerical method based on spur planetary gears [17,18,19,20,21]. Refs. [22, 23] investigate dynamic response of gear systems with Runge–Kutta method. Although numerical methods are sufficiently accurate, they are time-consuming and general results are difficult to obtain. However, studies using analytical method are rarely found. Zhang et al. [24] derived general formulations of dynamic response sensitivity with ideal model based on differential matrix theory. Liu et al. [25, 26] investigated response sensitivity of compound planetary gears. Yang [16] proposed a method based on the Fourier series and calculated sensitivity of forced vibration to mass and stiffness of helical planetary gears. This method is mathematically effective, though the relationships between sensitivity calculation and structured vibrations need further research.

As typical structured vibration, mesh phasing has been reported by the previous researchers [27, 28]. Parker et al. [29,30,31] studied the effects of mesh phasing in planetary gears and proved that it is based solely on system symmetry. Because of cyclic symmetry structure, such behaviors should still be found for RV reducer, where the phasing describes the link between parameters of high-speed stage, including planet gear number and sun gear tooth number, and those of low-speed stage, including the cycloid gear number and pin number, and forced vibration. However, whether it exists or not and to what degree basic parameters affects the structured vibration need to be studied.

The objective of this paper is to analytically study response sensitivity to parameters of RV reducer on the basis of cyclic symmetry structure. Therefore, a lumped parameter model was built up by incorporating various stiffness factors and the governing equation was derived and analytically solved. On the basis of analytical solution, response sensitivity to basic parameters was derived as closed-form expressions. The research is helpful for the analysis of response sensitivity and parameter selection of RV reducer.

2 Governing Equation of Motion

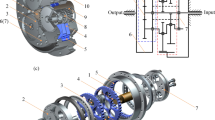

As shown in Figure 1, RV reducer is a two-stage closed planetary gear train, which consists of involute gears and cycloid gears. The high-speed stage is K-H type differential gears, including the sun, planets and output wheel. The low-speed stage is K-H-V type planetary gears, including crankshafts, cycloid gears, pinwheel and carrier. The carrier and output wheel are fixed together as one component.

A lumped parameter model [32, 33] is shown in Figure 2, where the pinwheel is considered as fixed, and the sun, M planets and crankshafts, N cycloid gears and output wheel are treated as rigid bodies. Component flexibility, bearings and gear meshes are represented by linear springs. The supports of the components are modeled as two perpendicular springs with equal stiffness. The transverse stiffness of the sun, planets, crankshafts, cycloid gears, and output wheel are designated as ks, ka, kHb, kcb and ko. The torsional stiffness of the sun, planet and output wheel are represented as kst, kH and kot. The gear meshes are modeled by springs acting along the line of action. The sun-planet and cycloid-pin mesh stiffness are ksi and kbj. The stiffness of the pinwheel is not taken into account in the modeling since it is much larger. The external torques are Ts and To which are respectively applied to the sun and output wheel.

The coordinates are also illustrated in Figure 2. Each component has two translational and one rotational motion. Thus the system has 6M + 3N + 6 degrees of freedoms. Using a fixed basis, translational coordinates (xs, ys) and (xo, yo) are assigned to the sun and output wheel, as shown in Figure 2(a). Coordinates (xpi, ypi), (xHi, yHi,) and (xcj, ycj) are respectively assigned to planet i, crankshaft i, and cycloid gear j, where i = 1, 2, …, M and j = 1, 2, …, N, as shown in Figure 2(b). Circumferential planet and cycloid gear locations are specified by the angles ψ i and ψ j . The xpi and xHi coordinates are chosen to be positive from the geometric center of the sun to that of the arbitrarily chosen first planet. The xcj coordinate is chosen to be positive from the geometric center of the pinwheel to that of the arbitrarily chosen first cycloid gear. All rotational coordinates are chosen to be θ which are positive in counterclockwise. This is illustrated in Figure 2, where θs, θpi, θHi, θci, and θo are respectively assigned to the sun, planets, crankshafts, cycloid gears and output wheel.

According to the Newton’s second law and theorem of angular momentum, the equations of motion for the sun, planets, crankshafts, cycloid gear and output wheel can be derived. Assembling the system equations and neglecting the gyroscopic effect, the governing equations of motion can be written in matrix form as

where M, Kb and Km are the inertia, support stiffness, and mesh stiffness matrices. F is the applied external torque. q is the generalized coordinate vector. They are given in the Appendix. The associated free vibration equation is

3 Primary Frequency Vibration From Mesh Stiffness

Response induced by mesh frequency excitation has structured behaviors due to the symmetry structure and mesh stiffness variation.

3.1 Primary Frequency Response

The governing equation is solved with Fourier series method. The stiffness matrix and generalized coordinate vector are rewritten as

where \({\bar{\varvec{K}}}\) is the average; \(\Delta {\varvec{K}}\) is the variable stiffness due to the time-varying mesh stiffness; \({\bar{\varvec{q}}}\) is the stationary deflection, and \(\Delta {\varvec{q}}\) is dynamic deflection induced by the mesh stiffness variation.

Substitution of Eqs. (3) and (4) into Eq. (1) gives

where \({\tilde{\varvec{F}}} = -\Delta {\varvec{K\bar{q}}}.\)

Expanding \(\Delta {\varvec{q}}\) and \({\tilde{\varvec{F}}}\) by Fourier series, harmonic expression of Eq. (5) becomes

where A1l and A2l are the cosine and sine components of \({\tilde{\varvec{F}}}\); B1l and B2l are those of \(\Delta {\varvec{q}}\), and ω l is the lth frequency.

Eq. (6) can be rewritten as

where \({\varvec{\varLambda}}\), B l and A l are given in the Appendix.

The lth amplitude of the response is

where \(\tau\;=\;1,\; 2,\;3, \ldots ,{ 6}M{ + 3}N{ + 6} .\)

The dynamic response of the τth freedom is

Please note that Eq. (1) describes a parametric vibration, but the derivation above ignores a so-called second order term \(\Delta {\varvec{K}}\Delta {\varvec{q}}\), which transfers the original parametric vibration to a forced one. Parametric vibration includes basic frequency and side frequency. The derivation here retains basic frequency and removes side frequency which has less influence on vibration than basic frequency [34, 35]. So this paper only studies primary frequency of parametric vibration of RV reducer.

3.2 Typical Vibration Modes at Primary Frequency

Ref. [30] shows by the vector addition of forces and moments that planetary gears exist typical vibration modes: rotational, translation and planet modes. The conclusion is based solely on the mesh force periodicity and system symmetry. Due to cyclic symmetry structure, RV reducer should have similar typical vibration modes as planetary gears, which is demonstrated by simulation in Section 3.3. Therefore, for RV reducer with M planets and crankshafts and N cycloid gears, the forced vibration has a well-defined structure. There are three typical vibration modes: rotational, translational and planetary component modes. The properties of each mode are summarized as below.

3.2.1 Rotational Modes

The translational forced vibrations of the sun and output wheel are suppressed due to mesh phasing. Thus they have pure rotational response. The planet components have identical deflection. A rotational mode has the form

where \({\varvec{B}}_{{hl{\text{s}}}} = \left( {0, \, 0, \, B_{hl}^{3} } \right),\,{\varvec{B}}_{{hl{\text{o}}}} { = }\left( {0, \, 0, \, B_{hl}^{6M + 3N + 6} } \right),\,h = 1,\;2.\)

3.2.2 Translational Modes

The rotational forced vibrations of the sun and output wheel are suppressed due to mesh phasing. In other words, the two central components have pure translational response. A translational mode has the form

where \({\varvec{B}}_{{hl{\text{s}}}} = \left( {B_{hl}^{1} , \, B_{hl}^{2} , \, 0} \right),\,{\varvec{B}}_{{hl{\text{o}}}} { = }\left( {B_{hl}^{6M + 3N + 4} , \, B_{hl}^{6M + 3N + 5} , \, 0} \right),\,h = 1, \, 2.\)

3.2.3 Planetary Component Modes

Planetary component modes exist when the number of planet and crankshaft or cycloid gear is greater than three. However, RV reducer scarcely contains so many planetary components. So the investigation of planetary component modes is solely as the theoretical research. The rotational and translational vibrations of the sun and output wheel are suppressed, and only planetary components have motion. A planetary component mode has the form

3.3 Numerical Results on Vibration Modes

To study the forced vibration of RV reducer, dynamic analysis is conducted with the operating speed of the sun 1000 r/min and the rated torque 3136 Nm. There are four planets, crankshafts and three cycloid gears. The governing equation is solved by the Fourier series method with parameters and stiffness in Tables 1 and 2. The response is approximated by the first nine harmonics.

Figure 3 shows the time domain response of the output wheel. It can be observed that the translational vibration of the output wheel is mainly affected by the mesh excitation of high-speed stage and the rotational vibration is affected by both the high-speed and low-speed stages.

Figure 4 shows the vibrations for a range of sun speeds. The mesh frequency ranges are 0–2500 Hz. The peaks corresponding to resonance response at the natural frequency ω l excited at the lth harmonic should occur at the mesh frequency of ω l /l. However, the resonant peaks corresponding to different natural frequency are not excited at all harmonics. In Figure 4(a), frequencies at ①, ②, and ③ associated with translational modes show resonant peaks. Peaks at ④ and ⑤ are corresponding to ② and ③ at the third and fifth harmonics. The other peaks at the two harmonics do exist. They are small but present. Refined increments of mesh frequency would make them more apparent. However, the natural frequencies which are associated with rotational and planetary component modes do not show resonant peaks at all harmonics.

Similar situation occurs in Figure 4(b). The frequencies associated with rotational modes show resonant peaks, but the frequencies associated to the other two modes do not show peaks. In Figures 4(c) and (d), the frequencies corresponding to all three modes show resonant peaks. The peaks at ① and ② in Figure 4(c) are associated with planetary component modes.

Obviously, the result in Figure 4 shows that RV reducer has typical forced vibration modes: translational, rotational and planetary component modes. However, RV reducer scarcely has more than three planetary components. The calculated results verify conclusions in Section 3.2 due to cyclic symmetry of RV reducer. The typical vibration modes can be used to simply the formula of response sensitivity.

4 Response Sensitivity to Parameters

With the response indicated by Eq. (8), one can obtain response sensitivity to design parameters. Differentiation of Eq. (8) with respect to a parameter \(\xi\) leads to

where parameter \(\xi\) can be arbitrary; \(B_{1l}^{\tau }\) and \(B_{2l}^{\tau }\) can be calculated by using Eq. (6). Thus the issue comes down to the differential of \(B_{1l}^{\tau }\) and \(B_{2l}^{\tau }\) to \(\xi\). Differentiation of Eq. (7) with respect to \(\xi\) gives

Moving the first term to the right hand side and premultiplying the inverse matrix of \({\varvec{\varLambda}}\) gives

where \({\varvec{G}} = {{\partial {\varvec{\varLambda}}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\partial {\varvec{\Lambda}}} {\partial \xi }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\partial \xi }}\). From Eq. (15), one can have the lth harmonic response sensitivity \({{\partial B_{1l}^{\tau } } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\partial B_{1l}^{\tau } } {\partial \xi }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\partial \xi }}\) and \({{\partial B_{2l}^{\tau } } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\partial B_{2l}^{\tau } } {\partial \xi }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\partial \xi }}\).According to Eq. (9), response sensitivity S is

With the obtained three typical vibration modes, one can have corresponding response sensitivity as follows.

4.1 Sensitivity of Rotational Modes

For a rotational mode, substitution of Eq. (10) into Eq. (15) gives

where \({\varvec{B}}_{{l{\text{R}}}} = \left( {{\varvec{B}}_{{1l{\text{R}}}} ,\;{\varvec{B}}_{{2l{\text{R}}}} } \right)^{\text{T}} .\)

To rotational modes, when \(\xi\) denotes transverse support stiffness of central components, only translational position of central components of G has terms. Besides, BlR has terms only corresponding to rotational position of central components. It is a zero vector with BlR premultiply by G which means the forced vibration of rotational modes is independent of transverse support stiffness of the central components. Thus, there is no need to calculate sensitivity of the forced vibration of rotational modes to transverse support stiffness. It can reduce the calculation time and provide some rules to suppress harmful vibration.

4.2 Sensitivity of Translational Modes

For a translational mode, substitution of Eq. (11) into Eq. (15) gives

where \({\varvec{B}}_{{l{\text{T}}}} = \left( {{\varvec{B}}_{{1l{\text{T}}}} ,\;{\varvec{B}}_{{2l{\text{T}}}} } \right)^{\text{T}} .\)

Similar to rotational modes, sensitivity of the forced vibration of translational modes to torsional stiffness of central components is zero which means the forced vibration of translational modes is independent of torsional stiffness of the central components.

4.3 Sensitivity of Planetary Component Modes

For a planetary component mode, substitution of Eq. (12) into Eq. (15) gives

where \({\varvec{B}}_{{l{\text{P}}}} = \left( {{\varvec{B}}_{{1l{\text{P}}}} ,\;{\varvec{B}}_{{2l{\text{P}}}} } \right)^{\text{T}} .\)

Sensitivity of the vibration of planetary component modes to both translational and torsional stiffness of central components is zero, implying these modes are insensitive to stiffness of the central components.

5 Numerical Results on Response Sensitivity to Parameters

5.1 Sensitivity to Stiffness

Response sensitivity to stiffness parameters can be calculated based on derivation in Section 4. Figure 5 shows the sensitivity of the vibration of the output wheel to support and torsional stiffness of the sun ks and kst for a range of sun speeds. The mesh frequency related to the sun speed ranges from 0 Hz to 2500 Hz. In Figure 5(a), the peak curves corresponding to resonant response occur when mesh frequency coincides with the first and second natural frequencies associated with translational modes. The resonant curves arise slowly as the support stiffness increases, because the natural frequencies arise with an increase in the stiffness. Likewise, similar behaviors can be found in Figure 5(b). The results can help choose working condition from the perspective of sensitivity.

Besides, response sensitivity to stiffness parameters at constant speed is also studied. Figure 6 respectively compares response sensitivity of the vibration of the output wheel to support and torsional stiffness of the sun ks and kst at 1000 r/min and 2000 r/min. In Figure 6(a), sensitivity decreases nonlinearly as support stiffness increases and flattens out when stiffness is high. The speed has more influence when support stiffness is low. Similar phenomenon happens to torsional stiffness in Figure 6(b).

5.2 Sensitivity to Mass and Moment of Inertia

Response sensitivity to mass and moment of inertia parameters follows the same procedure as stiffness. Figure 7 shows sensitivity of the vibration of the output wheel to mass ms and moment of inertia Js of the sun for a range of sun speeds. In Figure 7(a), the peak curves corresponding to resonant response occur when mesh frequency coincides with natural frequencies associated with translational vibration modes. The resonant curves decrease as mass and moment of inertia increase. It is because that the natural frequencies decrease as mass and moment of inertia increase. Likewise, similar situation appears in Figure 7(b). Moreover, compared Figure 7(a) with Figure 5(a), it suggests that translation of the output wheel is more sensitive to mass of the sun than the support stiffness. Compared Figure 7(b) with Figure 5(b), it implies that rotation of the output wheel is more sensitive to the torsional stiffness of the sun than the moment of inertia.

Figure 8 respectively compares sensitivity of the vibration of the output wheel to mass and moment of inertia of the sun ms and Js at 1000 r/min and 1250 r/min. In Figure 8(a), sensitivity increases as mass of the sun increases and gradually leads to steep when mass is large. The speed has more influence when the mass of the sun is large. Similar phenomenon occurs to moment of inertia in Figure 8(b).

5.3 Sensitivity to Eccentricity

Figure 9 shows response sensitivity of the vibration of the output wheel to eccentricity for a range of sun speeds. In Figure 9(a), the peak curves corresponding to resonant response occur when mesh frequency coincides with natural frequencies associated with both translational and rotational vibration modes. It suggests that eccentricity has influence on both translational and rotational vibration. The resonant curves corresponding to both modes arise as eccentricity increases. It is because that stiffness becomes larger when eccentricity increases.

Figure 10 compares response sensitivity of the vibration of the output wheel to eccentricity at constant speed. In Figure 10(a), the curve initially decreases and then increases as eccentricity increases. The speed has more influence on response for smaller eccentricity. In Figure 10(b), both curves increase when eccentricity increases, but for large speed they increase rapidly. It implies that the vibration is more sensitive to eccentricity for higher speeds.

The above results imply that sensitivity of some typical forced vibration occur peaks when mesh frequency coincides with natural frequency. To stiffness parameters, the vibration is more sensitive as stiffness is low. However, to mass and inertia parameters, the vibration is more sensitive as they are large.

6 Experiments

The dynamic testing experiments are performed with engineering prototype. The dynamic testing setup is shown in Figure 11. The speed of the sun is controlled by the servo motor. The load is replaced with inertia plate. Vibration signal is collected by accelerometers mounted on the inertia plate and disposed by LMS TEST.Lab. The experimental results are listed in Table 3 and compared to analytical results calculated by Eq. (2).

Table 3 shows the first three natural frequencies obtained from dynamic testing and analytical calculation. Results of two methods are in good agreement and the maximum amplitude difference is within 4%, which verifies the effectiveness of the analytical dynamic model.

7 Conclusions

-

(1)

RV reducer is a two-stage planetary gear train with cyclic symmetry structure. A dynamic model of RV reducer is established by incorporating bearing stiffness, crankshaft stiffness and mesh stiffness. The central components and an arbitrary number of planetary components are considered.

-

(2)

Typical forced vibration modes are verified and the properties are identified. There are three typical vibration modes: rotational, translational and planetary component modes. For each mode, vibration in certain harmonics of mesh frequency is suppressed.

-

(3)

Response sensitivity of three typical vibration modes to parameters are derived and expressed in closed-form formula with the typical modes. The vibration is more sensitive to stiffness as it is low. On the contrary, the vibration is more sensitive to mass and inertia as they are large.

-

(4)

Eccentricity has influence on both translational and rotational vibration of the output wheel. Sensitivity to translation decreases first and then increases as eccentricity increases, but to rotation it always increases. Vibration is more sensitive to eccentricity for higher speeds.

References

M Blagojevic, V Nikolic-Stanojevic, N Marjanovic, et al. Analysis of cycloid drive dynamic behavior. Scientific Technical Review, 2009, 59(1): 52.

L Pascale, M Neagoe, D Diaconescu, et al. The dynamic modeling of a new cycloidal planetary gear pair with rollers used in robots orientation system. The Scientific Bulletin of Electrical Engineering Faculty, 2009, 1: 10.

Y H Zhang, J J **ao, W D He. Dynamical formulation and analysis of RV reducer. International Conference on Engineering and Computation, 2009: 201–204.

Y H Zhang, W D He, J J **ao. Dynamical model of RV reducer and key influence of stiffness to the nature character. The Third International Conference on Information and Computing, 2010: 192–195.

S V Thube, T R Bobak. Dynamic analysis of a cycloidal gearbox using finite element method. AGMA Technical Paper, 2012: 1–13.

C F Hsieh. Dynamics analysis of cycloidal speed reducers with pinwheel and nonpinwheel designs. Journal of Mechanical Design, 2014, 136(9): 091008.

H Zhao, Q L Wu. Application study of fractal theory in mechanical transmission. Chinese Journal of Mechanical Engineering, 2016, 29(5): 871–879.

A Saada, P Velex. An extended model for the analysis of the dynamic behavior of planetary trains. Journal of Mechanical Design, 1995, 117(2): 241–247.

A Kahraman. Natural modes of planetary gear trains. Journal of Sound and Vibration, 1994, 173(1): 125–130.

C C Zhu, X Y Xu, T C Lim, et al. Effect of flexible pin on the dynamic behaviors of wind turbine planetary gear drives. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part C: Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science, 2013, 227(1): 74–86.

J Lin, R G Parker. Sensitivity of planetary gear natural frequencies and vibration modes to model parameters. Journal of Sound and Vibration, 1999, 228(1): 109–128.

Y Guo, R G Parker. Sensitivity of general compound planetary gear natural frequencies and vibration modes to model parameters. Journal of Vibration and Acoustics, 2010, 132(1): 011006.

B Qian, S J Wu. The research on natural characteristic and eigensensitivity of Ravingneaux compound planetary gear sets. Applied Mechanics and Materials, 2014, 446: 590–596.

W Sun, X Ding, J Wei, et al. An analyzing method of coupled modes in multi-stage planetary gear system. International Journal of Precision Engineering and Manufacturing, 2014, 15(11): 2357–2366.

W Sun, X Ding, J Wei, et al. A method for analyzing sensitivity of multi-stage planetary gear coupled modes to modal parameters. Journal of Vibroengineering, 2015, 17(6): 3133–3146.

T Q Yang. A study on dynamics of helical planetary gear train. Tian** University, 2004. (in Chinese).

P Velex, L Flamand. Dynamic response of planetary trains to mesh parametric excitations. Journal of Mechanical Design, 1996, 118(1): 7–14.

Z Chen, Y Shao, D Su. Dynamic simulation of planetary gear set with flexible spur ring gear. Journal of Sound and Vibration, 2013, 332(26): 7191–7204.

T M Ericson, R G Parker. Planetary gear modal vibration experiments and correlation against lumped-parameter and finite element models. Journal of Sound and Vibration, 2013, 332(9): 2350–2375.

T M Ericson, R G Parker. Experimental measurement of the effects of torque on the dynamic behavior and system parameters of planetary gears. Mechanism and Machine Theory, 2014, 74: 370–389.

I Miguel, F D R Alfonso, D J A Magdalena, et al. Planetary gear profile modification design based on load sharing modelling. Chinese Journal of Mechanical Engineering, 2015, 28(4): 810–820.

J Zhang, F Guo. Statistical modification analysis of helical planetary gears based on response surface method and Monte Carlo simulation. Chinese Journal of Mechanical Engineering, 2015, 28(6): 1194–1203.

S Zhou, G Song, Z Ren, et al. Nonlinear dynamic analysis of coupled gear-rotor-bearing system with the effect of internal and external excitations. Chinese Journal of Mechanical Engineering, 2016, 29(2): 281–292.

Y M Zhang, H Li, B C Wen. Parameter contribution analysis of vibration transfer paths based on sensitivity. Chinese Journal of Mechanical Engineering, 2008, 44(10): 168–171.

H Liu, Z C Cai, H X Cao, et al. Sensitivity analysis of forced torsional vibration on vehicle powertrain. Acta Armamentarii, 2011, 32(8): 939–944.

Z H Liu. Research on dynamic characteristics of vehicle compound planetary gear train sets. Wuhan University, 2012. (in Chinese).

A Kahraman, G W Blankenship. Planet mesh phasing in epicyclic gear sets. Proceedings of International Gearing Conference, Newcastle UK, 1994: 99–104.

G W Blankenship, A Kahraman. Gear dynamics experiments, Part I: Characterization of forced response. ASME Power Transmission and Gearing Conference, San Diego CA, 1996: 373–380.

R G Parker, V Agashe, S M Vijayakar. Dynamic response of a planetary gear system using a finite element/contact mechanics model. Journal of Mechanical Design, 2000, 122(3): 304–310.

R G Parker. A physical explanation for the effectiveness of planet phasing to suppress planetary gear vibration. Journal of Sound and Vibration, 2000, 236(4): 561–573.

V K Ambarisha, R G Parker. Suppression of planet mode response in planetary gear dynamics through mesh phasing. Journal of Vibration and Acoustics, 2006, 128(2): 133–142.

J Lin, R G Parker. Analytical characterization of the unique properties of planetary gear free vibration. Journal of Vibration and Acoustics, 1999, 121: 316–321.

D R Kiracofe, R G Parker. Structured vibration modes of general compound planetary gear systems. Journal of Vibration and Acoustics, 2007, 129: 1–16.

D S Zhang, S Y Wang. Parametric vibration of split gears induced by time-varying mesh stiffness. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part C: Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science, 2015, 229(1): 18–25.

J Lin, R G Parker. Planetary gear parametric instability caused by mesh stiffness variation. Journal of Sound and Vibration, 2002, 249(1): 129–145.

Authors’ Contributions

Y-HY was in charge of the whole trial; Y-HY, CC and S-YW wrote the manuscript; CC assisted with sampling and laboratory analyses. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ Information

Yu-Hu Yang, born in 1962, is currently a professor at School of Mechanical Engineering, Tian** University, China. His research interests include theory of mechanism and machinery dynamics. Tel: +86-13502108719; E-mail: Yangyuhu@tju.edu.cn.

Chuan Chen, born in 1985, is currently a PhD candidate at School of Mechanical Engineering, Tian** University, China. He received his bachelor and master degree from Northeastern University, China. His research interests include gear dynamics. E-mail: chenchuan1985728@126.com.

Shi-Yu Wang, born in 1974, is currently an associate professor at School of Mechanical Engineering, Tian** University, China. His research interests include machinery dynamics. E-mail: wangshiyu@tju.edu.cn.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Funding

Supported by National Hi-tech Research and Development Program of China (863 Program, Grant No. 2011AA04A102), National Nature Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 51175370), Application of Basic Research and Frontier Technology Research Key Projects of Tian** (Grant No. 13JCZDJC34300).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

\({\varvec{M}} = {\text{diag}}\left( {\varvec{M}_{s} \,\varvec{M}_{{{\text{p}}1}} \cdots {\varvec{M}}_{{{\text{p}}M}} \,{\varvec{M}}_{{{\text{H}}1}} \cdots {\varvec{M}}_{{{\text{H}}M}} \,{\varvec{M}}_{{{\text{c}}1}} \cdots {\varvec{M}}_{{{\text{c}}N}} \,{\varvec{M}}_{\text{o}} } \right)\)\({\varvec{M}}_{\nu } = {\text{diag}}\left( {m_{\nu } \,m_{\nu } \,J_{\nu } } \right)\), where \(\nu = {\text{s,}}\) \({\text{p}}1\; \cdots \;{\text{p}}M,\;{\text{H}}1\; \cdots \;{\text{H}}M,\;{\text{c}}1\; \cdots \;{\text{c}}N,\;{\text{o,}}\)\({\varvec{K}}_{\text{b}} = \left( {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {{\varvec{K}}_{ 1 1} } & \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} \\ \varvec{0} & {{\varvec{K}}_{ 2 2} } & {{\varvec{K}}_{ 2 3} } & \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} \\ \varvec{0} & {\left( {{\varvec{K}}_{ 2 3} } \right)^{\text{T}} } & {{\varvec{K}}_{ 3 3} } & {{\varvec{K}}_{ 3 4} } & {{\varvec{K}}_{ 3 5} } \\ \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} & {\left( {{\varvec{K}}_{ 3 4} } \right)^{\text{T}} } & {{\varvec{K}}_{ 4 4} } & \varvec{0} \\ \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} & {\left( {{\varvec{K}}_{ 3 5} } \right)^{\text{T}} } & \varvec{0} & {{\varvec{K}}_{ 5 5} } \\ \end{array} } \right),\)\({\varvec{K}}_{ 1 1} = {\text{diag}}\left( {k_{\text{s}} \,k_{\text{s}} \,k_{\text{st}} } \right),\)

\(\begin{aligned} {\varvec{K}}_{\text{m}} = \hfill \\ \left( {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {\sum\limits_{i} {{\varvec{K}}_{{{\text{s}}1}}^{i} } } & {{\varvec{K}}_{{{\text{s}}2}}^{1} } & \cdots & {{\varvec{K}}_{{{\text{s}}2}}^{M} } & \varvec{0} & \cdots & \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} & \cdots & \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} \\ {({\varvec{K}}_{{{\text{s}}2}}^{1} )^{\text{T}} } & {{\varvec{K}}_{\text{pp}} } & \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} & \cdots & \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} & \cdots & \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} \\ \vdots & \varvec{0} & \ddots & \varvec{0} & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots & \vdots \\ {({\varvec{K}}_{{{\text{s}}2}}^{M} )^{\text{T}} } & \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} & {{\varvec{K}}_{\text{pp}} } & \varvec{0} & \cdots & \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} & \cdots & \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} \\ \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} & \cdots & \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} & \cdots & \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots & \varvec{0} & \ddots & \varvec{0} & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots & \vdots \\ \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} & \cdots & \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} & \cdots & \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} \\ \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} & \cdots & \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} & \cdots & \varvec{0} & {{\varvec{K}}_{\text{cr}} } & \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots & \varvec{0} & \ddots & \varvec{0} & \vdots \\ \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} & \cdots & \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} & \cdots & \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} & {{\varvec{K}}_{\text{cr}} } & \varvec{0} \\ \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} & \cdots & \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} & \cdots & \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} & \cdots & \varvec{0} & \varvec{0} \\ \end{array} } \right), \hfill \\ \end{aligned}\)\({\varvec{K}}_{{{\text{s}}1}}^{i} = k_{{{\text{s}}i}} \left( {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {\cos^{2} \psi_{{{\text{s}}i}} } & {\cos \psi_{{{\text{s}}i}} \sin \psi_{{{\text{s}}i}} } & {r_{\text{s}} \cos \psi_{{{\text{s}}i}} } \\ {\cos \psi_{{{\text{s}}i}} \sin \psi_{{{\text{s}}i}} } & {\sin^{2} \psi_{{{\text{s}}i}} } & {r_{\text{s}} \sin \psi_{{{\text{s}}i}} } \\ {r_{\text{s}} \cos \psi_{{{\text{s}}i}} } & {r_{\text{s}} \sin \psi_{{{\text{s}}i}} } & {r_{\text{s}}^{2} } \\ \end{array} } \right),\)

\({\varvec{B}}_{l} = \left( {{\varvec{B}}_{{_{1l} }}^{\text{T}} \,{\varvec{B}}_{2l}^{\text{T}} } \right)^{\text{T}} ,\) \({\varvec{A}}_{l} = \left( {{\varvec{A}}_{1l}^{\text{T}} \,{\varvec{A}}_{2l}^{\text{T}} } \right)^{\text{T}} .\)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, YH., Chen, C. & Wang, SY. Response Sensitivity to Design Parameters of RV Reducer. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 31, 49 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s10033-018-0249-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s10033-018-0249-y