Abstract

Background

The aim of this 12-month study in pre-pubertal children was to evaluate the effect of school transportation on gain in lean and fat mass, muscle strength and physical performance.

Methods

Ninety-seven girls and 133 boys aged 7-9 years from the Malmö Pediatric Osteoporosis Prevention Study were included. Regional lean and fat mass were assessed by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry, isokinetic peak torque of knee extensors and flexors by a computerised dynamometer and physical performance by vertical jump height. Level of physical activity was assessed by accelerometers. The 12-month changes in children who walked or cycled to school were compared with changes in those who travelled by bus or car.

Results

There were no differences in baseline or annual changes in lean or fat mass gain, muscle strength or physical performance between the two groups. All children reached the internationally recommended level of 60 minutes per day of moderate or high physical activity by accelerometers.

Conclusion

The choice of school transportation in pre-pubertal children seems not to influence the gain in lean and fat mass, muscle strength or functional ability, probably as the everyday physical activity is so high that the mode of school transportation contributes little to the total level of activity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Regular participation in physical activity during childhood is regarded as one of the most important lifestyle factors that can improve musculoskeletal health, fitness and body composition [1, 2]. Although most chronic diseases associated with physical inactivity seldom become manifest before adulthood, promotion of physical activity during youth is important as low physical activity during childhood is associated with risk factors for diseases in adulthood [3]. Furthermore, low levels of physical activity during childhood predisposes to a future sedentary lifestyle that further increases the risk of disease [4, 5].

Although, physical activity is regarded as beneficial for musculoskeletal development [1, 2, 6, 7], many children do not engage in regular physical activity. The journey to school is regarded as one opportunity to implement regular physical activity in school children. Cross-sectional studies support the effectiveness of this approach when reporting that cycling and walking to school confer higher levels of physical activity and improved fitness than going by bus or car [8–11]. But, to our knowledge there are no prospective trials that support this notion. This is why this study was designed to evaluate in a population-based cohort of pre-pubertal Swedish children whether walking and cycling to school for one year was associated with improved physical performance, higher gain in muscle mass and low gain in fat mass compared to commuting by car or bus.

Materials and methods

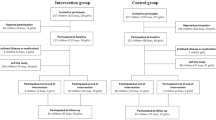

The Malmö Paediatric Osteoporosis Prevention (POP) Study is a prospective exercise intervention study. As described previously [12, 13], the trial is designed to assess musculo-skeletal development in children when they commence school. Fifty-three girls and 81 boys aged 7-9 years were included in a school curriculum based general physical activity programme for 40 minutes/day (200 minutes/week). Fifty girls and 57 boys matched for age, assigned to the general school curriculum of physical activity (60 min/week), served as controls. Since the purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of differences in transport to school, the children were pooled. Children going to school by walking and cycling were compared with children who travelled by car or bus. All participants were Caucasians except one adopted boy from Colombia. All were healthy, without medication known to influence bone or muscle metabolism. As described in previous publications, no differences were found between the study participants and non-participants regarding height, weight and body mass index (BMI) [12, 13]. Written informed consent was obtained from parents or guardians prior to participation. The Ethical Committee of Lund University approved the study.

A questionnaire was used to evaluate lifestyle factors such as school transportation, diseases and weekly duration of organised physical activity. The question on school transportation was asked yearly and included information as regard school transportation during winter and summer seasons. There were three possible answers: walking, cycling or going by car or bus. If the children changed their mode of transportation repeatedly or used different kinds of transportation during different seasons they were excluded. As 6 girls and 5 boys did not answer the question on mode of school transportation or used several modes of transportation, only 97 girls and 133 boys were included in this study. Sixty girls, of which 30 were registered in the intervention group and 30 in the control group, and 75 boys, of which 34 were registered in the intervention group and 41 in the control group, walked or cycled to school. Thirty-seven girls, of whom 18 were registered in the intervention group and 19 in the control group, and 58 boys, of whom 43 were registered in the intervention group and 15 in the control group, commuted to school by car or bus.

Subjective estimated level of physical activity was calculated as the sum of the duration of physical education at school and the duration of organised leisure time physical activity. The mean values of the duration of physical activity during summer and winter seasons were used.

Tanner staging [14] was used by the research nurse to assess the maturity status of the children both at baseline and at follow-up. All children remained in Tanner stage 1 during the entire study period. Body weight was measured with an electric scale to the nearest 0.1 kg and height by a wall mounted height measure to the nearest 0.5 cm. BMI was calculated as weight/height2 (kg/m2). Total body, arms and legs lean tissue mass (kg) and fat mass (kg) were measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA, DPX-L version 1.3z, Lunar®, Madison, WI). The precision, evaluated by duplicate measurements in 13 healthy children, was 3.7% for total body fat mass and 1.5% for total body lean tissue mass.

Concentric isokinetic knee extension and flexion peak torque was tested at an angular velocity of 60 and 180°/sec using a computerised dynamometer, (Biodex System 3®). The knee was positioned at 90° of flexion and went through a 75° range of motion, stop** at 15° of flexion. Peak torque (Nm) at both 60 and 180°/sec for extension (PTEx60; PTEx180) and flexion (PTFl60; PTFl180) were expressed as Nm/kg. The intra-individual test variability, evaluated as the coefficient of variation for repeated measurements in 21 children, was 6.6% for PTEx60, 12.1% for PTFl60, 12.3% for PTEx180, and 9.1% for PTFl180.

Vertical jump height was assessed as an estimate of physical performance. The vertical jump test was performed on an electronic mat connected to a digital timer that registered the total time in the air. From these data, the height of the jump in centimetres was automatically calculated by the computer included in the standard equipment. All vertical jumps were performed from a standing position, and participants were first required to jump onto the mat with both feet, and then make a maximal vertical jump. Each subject performed three vertical jumps of which the highest jump (cm) was recorded. The intra-individual test variability, evaluated as the coefficient of variation for repeated measurements in 21 children, was 5.9%.

Methodology of physical activity measurement has previously been presented in detail [1, 15, 16]. Physical activity was assessed using the MTI accelerometer, model 7164 for four consecutive days. Accelerometer data are averaged over a period of time called an epoch. A recording epoch of ten seconds was selected for this study. A SAS-based software was used to analyse all accelerometer data. This software automatically deletes missing data, defined as continuous sequences of 60 consecutive epochs (i.e. 10 minutes) or more with zero counts. This was done based on the assumption that all such sequences of zeroes lasting longer than ten minutes were caused by the accelerometer not being worn. In order to minimise inter-instrumental variation, all accelerometers were calibrated against a standardised vertical movement. Mean activity was considered to be the total accelerometer counts per valid minute of monitoring (mean counts/min). Time spent performing above 3 METs was considered to reflect moderate to vigorous activity (MVPA), and time spent above 6 METs was considered to reflect vigorous activity (VPA). Cut-off points used for all children were > 167 counts/epoch for MVPA and > 583 counts/epoch for VPA [17, 18].

Baseline measurements were performed at the commencement of school. Follow-up evaluations were done the same month one year later in the intervention group and two years later in the control group. Changes per 365 days were calculated. However, all the children stayed pre-pubertal in Tanner stage I during the study and pre-pubertal growth seems to be linear. One Swedish study reported that the growth rates in children are linear from age six to peak height velocity. In girls peak height velocity is usually reached at a mean age of 11.7 years in Tanner stage III, whereas peak bone mineral accrual occurs at a mean age of 12.5 years in Tanner stage IV [19]. In boys both peak height velocity and peak bone mineral accrual are reached at an even higher age [19]. These observations are supported in Australian children [20], in which peak bone mass accrual and peak height velocity occurred in Tanner stage II or later, whereas the growth and bone mineral accrual were linear in Tanner stage I and during the ages followed in this study. The finding of a linear increase in accrual of bone mineral and bone size in the indicated age group and the observation that the increase in bone traits first occurs in Tanner stage II or even later are corroborated by the results of several investigations of independent cohorts of children [19–27]. Based on the consistency of this extensive literature, our study design comparing the annual changes was regarded as acceptable, even if not ideal.

Statistical calculations were performed with SPSS for Windows version 14.0. All data are presented as means (SD). The girls and boys who walked or cycled were compared with those who commuted by bus or car using two-tailed independent student t-tests between means and Fisher exact test. Analysis covariance (ANCOVA) was then used to adjust for subjective estimated duration of organised physical activity and study group (intervention or control group). A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

No significant differences were found at baseline for any of the lifestyle factors, anthropometrics, muscle strength or functional capacity between girls and boys who walked or cycled to school compared to those who travelled by car or bus (Table 1).

During the follow-up period, the gain in height, weight, BMI, body composition, muscle strength or functional capacity was no different for the two groups. After adjusting for subjective estimated levels of physical activity and study group (those with extra school exercise classes or not), these results remained unchanged for all variables except for lean mass total body in boys where we found a borderline significance (p = 0.05). In the accelerometer data, there was no difference in the level of physical activity when comparing the transportation groups. Furthermore, as previously published [14], the objectively measured accelerometer data revealed that all children fulfilled the international recommended level of 60 minutes of moderately intense physical activity per day [27]

Discussion

In this study, we found that there were no differences in objectively measured levels of physical activity or gains in lean mass, fat mass, muscle strength or functional performance when comparing children who walked or cycled to school to those who travelled by car or bus. This finding is likely to be explained by the fact that Swedish children participate in a relatively high level of everyday physical activity (Table 1). Thus, the contribution of walking or cycling to school to their total daily activity levels could be regarded as relatively insignificant, particularly since the average distance from home to school was only between 0.5 and 1.7 km. The accelerometer data provided further evidence that transportation mode did not influence daily activity levels and all children in this study met the international recommended level of 60 minutes of moderate or intense physical activity per day [15], set by the United Kingdom Expert Consensus Group [28]. Consistent with our findings, Metcalf et al. reported that walking to school was not associated with the daily levels of physical activity in children aged 5 years [29]. However, there is some evidence that transportation mode may be important for the development of physical performance in pubertal children [30, 31], particularly since general levels of everyday physical activity typically decline during adolescence [32]. Hypothetically, transportation mode could also be of importance in geographic areas with a long distance from home to school.

The general awareness of the health benefits associated with regular physical activity has led to several public health guidelines [3, 28, 33]. Most of these guidelines are based on subjective estimated level of physical activity, predominantly through questionnaires. However, previous research has shown that self-reported assessment of physical activity in children tends to overestimate vigorous activity and underestimate moderate activity [34, 35]. The introduction of accelerometers provides more objective measurements of physical activity and this new technique may improve our ability to make adequate health recommendations about sufficient level of physical activity, as indicated in studies by Dencker, Riddoch, Pate and Trost [15, 32, 36, 37]. For example, these studies indicate that 90 to 100% of children below the age of 10 meet the United Kingdom Expert Consensus Group recommended level of physical activity [28]. In contrast, the level of physical activity in adolescent boys and girls tends to be lower [32, 36, 37], indicating that transportation mode to school in these ages may be beneficial. This is supported by data showing that adolescents who walk to school have higher levels of daily physical activity than those going by car [30, 31].

Study strengths

An important strength of this study was the finding in the drop-out analyses that the children recruited for this study were a representative sample of Swedish children. Furthermore, the prospective study design and the similarity between the groups at inclusion provides a higher level of evidence with regard to the effects of transportation mode on health-related factors and physical activity levels compared to previously published cross-sectional studies. The use of accelerometers, as an objective estimation of daily physical activity, is also positive compared to subjective estimates of physical activity [34, 35].

Study limitations

The classification of transportation mode was made via the questionnaire without objective verification. The study was not randomised with the risk of selection bias. However, the two groups were well matched, and there were no differences in children who did and did not participate in this study. A selection of school transportation, more based on the distance to school than based on the phenotype of the child strengthens the view that there was no selection so that stronger children chose to walk or cycle. It would also have been an advantage if all four transportation modes could have been compared, however this was not possible due to the risk of conducting type II errors. The study design, with half of the children having 40 min/day of extra physical education, could also influence the inferences. However, we found children with different transportation modes in both the intervention and control groups and the results remained after adjusting for being in extra physical classes or not. Finally, the one-year follow-up in the children with extra physical classes and two-year follow-up in the control group could also create problems. However, this should not influence the inferences as we compared the exact annual changes, as all children stayed in Tanner stage I and as the literature infers that growth is linear during these years [19–22, 24–27, 38]. All results remained the same after including follow-up period as a covariate.

Conclusions

In 7-9-year old Swedish children with a high level of daily physical activity, the mode of transportation to school (walking/cycling versus car/bus) during one year did not influence the gain in lean mass, fat mass or physical performance. However, well-designed randomised controlled studies are required to determine the influence of transportation mode to school in children across different ages, school levels and regions (rural versus urban living).

References

Dencker M, Thorsson O, Karlsson MK, et al: Daily physical activity related to body fat in children aged 8-11 years. J Pediatr. 2006, 149 (1): 38-42. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.02.002.

Morris FL, Naughton GA, Gibbs JL, Carlson JS, Wark JD: Prospective ten-month exercise intervention in premenarcheal girls: positive effects on bone and lean mass. J Bone Miner Res. 1997, 12 (9): 1453-62. 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.9.1453.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 1996

Malina RM: Physical activity and fitness: pathways from childhood to adulthood. Am J Hum Biol. 2001, 13 (2): 162-72. 10.1002/1520-6300(200102/03)13:2<162::AID-AJHB1025>3.0.CO;2-T.

Telama R, Yang X, Laakso L, Viikari J: Physical activity in childhood and adolescence as predictor of physical activity in young adulthood. Am J Prev Med. 1997, 13 (4): 317-23.

Faigenbaum AD, Westcott WL, Loud RL, Long C: The effects of different resistance training protocols on muscular strength and endurance development in children. Pediatrics. 1999, 104 (1): e5-10.1542/peds.104.1.e5.

Ramsay JA, Blimkie CJ, Smith K, Garner S, MacDougall JD, Sale DG: Strength training effects in prepubescent boys. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1990, 22 (5): 605-14. 10.1249/00005768-199010000-00011.

Cooper AR, Andersen LB, Wedderkopp N, Page AS, Froberg K: Physical activity levels of children who walk, cycle, or are driven to school. Am J Prev Med. 2005, 29 (3): 179-84. 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.05.009.

Cooper AR, Page AS, Foster LJ, Qahwaji D: Commuting to school: are children who walk more physically active?. Am J Prev Med. 2003, 25 (4): 273-6. 10.1016/S0749-3797(03)00205-8.

Cooper AR, Wedderkopp N, Wang H, Andersen LB, Froberg K, Page AS: Active travel to school and cardiovascular fitness in Danish children and adolescents. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006, 38 (10): 1724-31. 10.1249/01.mss.0000229570.02037.1d.

Evenson KR, Huston SL, McMillen BJ, Bors P, Ward DS: Statewide prevalence and correlates of walking and bicycling to school. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003, 157 (9): 887-92. 10.1001/archpedi.157.9.887.

Linden C, Alwis G, Ahlborg H, et al: Exercise, bone mass and bone size in prepubertal boys: one-year data from the pediatric osteoporosis prevention study. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2007, 17 (4): 340-7.

Valdimarsson O, Linden C, Johnell O, Gardsell P, Karlsson MK: Daily physical education in the school curriculum in prepubertal girls during 1 year is followed by an increase in bone mineral accrual and bone width--data from the prospective controlled Malmo pediatric osteoporosis prevention study. Calcif Tissue Int. 2006, 78 (2): 65-71. 10.1007/s00223-005-0096-6.

Duke PM, Litt IF, Gross RT: Adolescents' self-assessment of sexual maturation. Pediatrics. 1980, 66 (6): 918-20.

Dencker M, Thorsson O, Karlsson MK, et al: Daily physical activity in Swedish children aged 8-11 years. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2006, 16 (4): 252-7. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2005.00486.x.

Dencker M, Thorsson O, Karlsson MK, et al: Daily physical activity and its relation to aerobic fitness in children aged 8-11 years. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2006, 96 (5): 587-92. 10.1007/s00421-005-0117-1.

Freedson PS, Melanson E, Sirard J: Calibration of the Computer Science and Applications, Inc. accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998, 30 (5): 777-81. 10.1097/00005768-199805000-00021.

Trost SG, Ward DS, Moorehead SM, Watson PD, Riner W, Burke JR: Validity of the computer science and applications (CSA) activity monitor in children. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998, 30 (4): 629-33. 10.1097/00005768-199804000-00023.

MacKelvie KJ, Khan KM, McKay HA: Is there a critical period for bone response to weight-bearing exercise in children and adolescents? a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2002, 36 (4): 250-7. 10.1136/bjsm.36.4.250.

Bass S, Delmas PD, Pearce G, Hendrich E, Tabensky A, Seeman E: The differing tempo of growth in bone size, mass, and density in girls is region-specific. J Clin Invest. 1999, 104 (6): 795-804. 10.1172/JCI7060.

Bailey DA, McKay HA, Mirwald RL, Crocker PR, Faulkner RA: A six-year longitudinal study of the relationship of physical activity to bone mineral accrual in growing children: the university of Saskatchewan bone mineral accrual study. J Bone Miner Res. 1999, 14 (10): 1672-9. 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.10.1672.

Bonjour JP, Theintz G, Buchs B, Slosman D, Rizzoli R: Critical years and stages of puberty for spinal and femoral bone mass accumulation during adolescence. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1991, 73 (3): 555-63. 10.1210/jcem-73-3-555.

Fournier PE, Rizzoli R, Slosman DO, Theintz G, Bonjour JP: Asynchrony between the rates of standing height gain and bone mass accumulation during puberty. Osteoporos Int. 1997, 7 (6): 525-32. 10.1007/BF02652557.

Glastre C, Braillon P, David L, Cochat P, Meunier PJ, Delmas PD: Measurement of bone mineral content of the lumbar spine by dual energy x-ray absorptiometry in normal children: correlations with growth parameters. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990, 70 (5): 1330-3. 10.1210/jcem-70-5-1330.

Kroger H, Kotaniemi A, Kroger L, Alhava E: Development of bone mass and bone density of the spine and femoral neck--a prospective study of 65 children and adolescents. Bone Miner. 1993, 23 (3): 171-82. 10.1016/S0169-6009(08)80094-3.

Liu YX, Wikland KA, Karlberg J: New reference for the age at childhood onset of growth and secular trend in the timing of puberty in Swedish. Acta Paediatr. 2000, 89 (6): 637-43. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2000.tb00356.x.

Theintz G, Buchs B, Rizzoli R, et al: Longitudinal monitoring of bone mass accumulation in healthy adolescents: evidence for a marked reduction after 16 years of age at the levels of lumbar spine and femoral neck in female subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992, 75 (4): 1060-5. 10.1210/jc.75.4.1060.

Cavill N, Biddle S, Sallis JF: Health enhancing physical activity for young people: Statement of the United Kingdom Expert Consensus Conference. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2001, 13 (1): 12-25.

Metcalf B, Voss L, Jeffery A, Perkins J, Wilkin T: Physical activity cost of the school run: impact on schoolchildren of being driven to school (EarlyBird 22). BMJ. 2004, 329 (7470): 832-3. 10.1136/bmj.38169.688102.F71.

Alexander LM, Inchley J, Todd J, Currie D, Cooper AR, Currie C: The broader impact of walking to school among adolescents: seven day accelerometry based study. BMJ. 2005, 331 (7524): 1061-2. 10.1136/bmj.38567.382731.AE.

Saksvig BI, Catellier DJ, Pfeiffer K, et al: Travel by walking before and after school and physical activity among adolescent girls. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007, 161 (2): 153-8. 10.1001/archpedi.161.2.153.

Riddoch CJ, Bo Andersen L, Wedderkopp N, et al: Physical activity levels and patterns of 9- and 15-yr-old European children. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004, 36 (1): 86-92. 10.1249/01.MSS.0000106174.43932.92.

Sallis JF, Patrick K: Physical activity guidelines for adolescents: Consensus statement. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 1994, 6: 302-14.

Kohl HW, Fulton JE, Caspersen CJ: Assessment of physical activity among children and adolescents: a review and synthesis. Prev Med. 2000, 31 (2): S54-76. 10.1006/pmed.1999.0542.

Sallis JF, Saelens BE: Assessment of physical activity by self-report: status, limitations, and future directions. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2000, 71 (2 Suppl): S1-14.

Pate RR, Freedson PS, Sallis JF, et al: Compliance with physical activity guidelines: prevalence in a population of children and youth. Ann Epidemiol. 2002, 12 (5): 303-8. 10.1016/S1047-2797(01)00263-0.

Trost SG, Pate RR, Sallis JF, et al: Age and gender differences in objectively measured physical activity in youth. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002, 34 (2): 350-5. 10.1097/00005768-200202000-00025.

Faulkner RA, McCulloch RG, Fyke SL, et al: Comparison of areal and estimated volumetric bone mineral density values between older men and women. Osteoporos Int. 1995, 5 (4): 271-75. 10.1007/BF01774017.

Acknowledgements

Financial support for this study was provided by the Swedish Research Council, the Centre for Athletic Research, the Region Skane Foundation, and the Österlund Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Stenevi-Lundgren, S., Daly, R.M., Gärdsell, P. et al. The increase in physical performance and gain in lean and fat mass occur in prepubertal children independent of mode of school transportation. One year data from the prospective controlled Pediatric Osteoporosis Prevention (POP) Study. Arch Public Health 67, 88 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1186/0778-7367-67-2-88

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/0778-7367-67-2-88