Abstract

Background

As SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variants circulating globally since 2022, assessing the transmission characteristics, and the protection of vaccines against emerging Omicron variants among children and adolescents are needed for guiding the control and vaccination policies.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study for SARS-CoV-2 infections and close contacts aged <18 years from an outbreak seeded by Omicron BA.5 variants. The secondary attack rate (SAR) was calculated and the protective effects of two doses of inactivated vaccine (mainly Sinopharm /BBIBP-CorV) within a year versus one dose or two doses above a year after vaccination against the transmission and infection of Omicron BA.5 were estimated.

Results

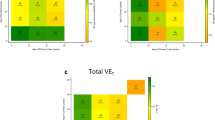

A total of 3442 all-age close contacts of 122 confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infections aged 0–17 years were included. The SAR was higher in the household setting and for individuals who received a one-dose inactivated vaccine or those who received a two-dose for more than one year, with estimates of 28.5% (95% credible interval [CrI]: 21.1, 37.7) and 55.3% (95% CrI: 24.4, 84.8), respectively. The second dose of inactivated vaccine conferred substantial protection against all infection and transmission of Omicron BA.5 variants within a year.

Conclusions

Our findings support the rollout of the second dose of inactivated vaccine for children and adolescents during the Omciron BA.5 predominant epidemic phase. Given the continuous emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants, monitoring the transmission risk and corresponding vaccine effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 variants among children and adolescents is important to inform control strategy.

Plain Language Summary

Children and adolescents have reported suffering less severe outcomes from the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. However, the risk of transmission and vaccine effectiveness among this population group is not well studied. Here, we used contact tracing data that was collected during an Omicron BA.5 outbreak from Urumqi, China, before the exit of “zero-COVID” measures, to evaluate the spread of SARS-CoV-2 infection among those age under 18 years, and the effectiveness of inactivated vaccine regimens. Our findings indicate there is a high rate of transmission among children and adolescents in a household setting and receiving two doses of inactivated COVID-19 vaccination within a year was more effective than a single dose or two doses given more than a year apart. These findings highlight the importance of tracking transmission and vaccine effectiveness of novel SARS-CoV-2 variants in younger populations to inform control strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variants dominated the COVID-19 pandemic in 2022. They were found with increased transmissibility1,2, and resistance from both naturally acquired and vaccine-elicited antibodies3,4, which was considered to be one of the major challenges for disease control. The Omicron variants continuously evolved with epidemiologic and virological characteristics for adaptation in the human population. As of 8 January 2023, the Omicron BA.5 subvariants are the dominating strain amidst the pandemic, accounting for 85.9% of viral sequences of human SARS-CoV-2 submitted to the Global Initiative on Sharing Avian Influenza Data (GISAID) from 9 December 2022 to 9 January 20235.

The increasing numbers of Omicron infections raised concerns, particularly for vulnerable populations including children and adolescents, who are often featured with higher contact rates (e.g., in school or household settings), and lower vaccine coverage than other age groups6. Although literature presented evidence suggesting that pediatric COVID-19 was rarely severe7,8,9, critical symptoms including the Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C)8,10 and long-COVID-19 may occur11. Besides, children and adolescents were found more susceptible to COVID-19 infection than adults, especially during an Omicron predominance phase12,13. Real-world observational studies demonstrated moderate effectiveness of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine (BNT162b2) against Omicron infection among children and adolescents14,15, and high vaccine effectiveness (VE) against hospitalization, death, and ICU admission16,17,18, though the protective effects waned quickly over time. To date, only a small number of studies have examined the VE of inactivated COVID-19 vaccines among children and adolescents19,20,21,22,23,24. Yet, none of these studies evaluated the VE against the Omicron subvariants (BA.5), which could provide additional insights into the protection of inactivated vaccines against the novel circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants.

From the standpoint of outbreak control, cutting off the transmission chain is one of the most effective measures apart from vaccination. Children and adolescents played an essential role in transmissions that occurred in household and school settings25,26. Despite early studies suggesting a lower transmission risk, as indicated by a lower secondary attack ratio (SAR) of children index cases than that of adult index cases for the ancestral SARS-CoV-2 strains27, children infected by the early Omicron variants were found more transmissible than adults28. Monitoring the transmission risks of children and adolescents infected by the emerging Omicron subvariants was urgently needed across different strata of risk factors and settings, given the rapid expansion of Omicron infections. Furthermore, the data regarding the VE against transmission among children and adolescents remains scarce29,30, which can shed light on the protection of vaccines against the risks of onward transmission seeded by children and adolescents.

From 1 August to 7 September 2022, Urumqi city, China experienced an outbreak seeded by the Omicron BA.5 variants. A series of stringent public health and social measures (PHSMs) have been implemented in response to the epidemics, including the city-wide lockdown, mass testing, contact tracing, and case isolation. Since August 3, 2021, China has recommended the inactivated vaccine rollout for children and adolescents aged 3–17 years, and Sinopharm (BBIBP-CorV) and Sinovac (CoronaVac) were the only two types of COVID-19 vaccine approved to be used in Urumqi city, where Sinopharm was the majority with >85% among vaccinated population (internal data from Urumqi CDC).

In this study, by leveraging detailed contact tracing data, we aim to assess the transmission characteristics of Omicron BA.5 among children and adolescents and the protective effectiveness of inactivated vaccines against the infection and transmission of the BA.5 variants. We estimate that the BA.5 variant has a relatively high risk of transmission among children and adolescents contacts in household while with considerable superspreading potential in non-household settings. We show that a second dose of inactivated vaccine within a year was associated with a substantial reduction in transmission risk in children and adolescents, as compared to a one-dose or dated second-dose vaccine. These findings underscore the need for monitoring the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines and the transmission potential among younger populations infected with emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Methods

Study design and participants

This was a retrospective cohort analysis for SARS-CoV-2 infections and close contacts aged 0–17 years during an Omicron BA.5 outbreak in Urumqi, China. Children and adolescent close contacts and infected, and their close contacts were included in the screening. Owning to the zero-COVID policy (implemented before November 2022) in mainland China, no large-scale COVID-19 outbreak occurred in Urumqi before August 2022, which means that the 3.8 million population was largely infection-naïve, and thereby the likelihood of re-infection was negligible. The COVID-19 vaccines received by almost all vaccinees in mainland China were Sinopharm and Sinovac vaccines, which were recommended and administered under the supervision of Chinese authorities for those aged over 3 years.

De-identified individual-level line-list surveillance data was obtained from the ** marts, restaurants, and entertainment settings) were conducted. Thus, the number of exposure or contact was generally lower in the population, which gave rise to a lower risk of infection and transmission. A study has shown that the protection conferred by the COVID-19 vaccine is dependent on the rate of exposure, with a higher level of exposure diminishing the effectiveness of vaccine against the Omicron infection47. Our VE estimates were also higher than that from a Hong Kong study, which indicated that the effectiveness of a two-dose CoronaVac vaccine was 55% against infection among 12–18 years old20. Since the beginning of the Omicron epidemic, Hong Kong has implemented a Vaccine Pass policy for individuals over 12 years old, whereby at least one dose of vaccine was required for entering public facilities. As such, vaccinated adolescents likely had a higher risk of infection because of being involved in various exposure settings as compared to an unvaccinated one, which may drive the VE downward. Moreover, previous data demonstrated that the Sinopharm vaccine had a higher relative effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 infection than the Sinovac-CoronaVac vaccine48, which may also contribute to explaining the difference in VE of the present study and that of the Brazilian and Chilean studies, given that the majority of the participants (>85%) received the Sinopharm vaccine. Additionally, a comparative study among adolescents aged 12–17 years old showed the effectiveness of a two-dose BNT162b2 vaccine against infection was much higher in Scotland (80.7%) than in Brazil (64.7%), and the VE waned at a much lower rate in Scotland compared to Brazil49. Therefore, the heterogeneity of the underlying population could also play an important role in determining the VE estimates. Our analysis for VE against the Omicron BA.5 infection showed that among children and adolescents, the risk of infection by the BA.5 variants for individuals who received a two-dose inactivated vaccine reduced by 92.4% within six months (75.4% for those who have received a two-dose inactivated vaccine for 181–365 days) (Supplementary Data 1), as compared to those who only received a one-dose inactivated vaccine and those who received the two-dose regimen for more than a year. Considering a one-dose vaccine only provided a weak immune response and protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection, and the immunity level would wane to a considerably lower level a year after receiving the second dose of the inactivated vaccine19,32,33,50, our reference group might represent the group of children and adolescents who have a relatively lower internal immunity induced by the vaccine. Furthermore, the estimated risk reduction not only reflected the additional protection conferred by a second dose of vaccine compared to a one-dose vaccine but also a waned VE. Given that the effectiveness of the inactivated vaccine against the Omicron variant tends to wane rapidly within months after the inoculation among children and adolescents23, along with the compromised immune response induced by the vaccine51, a booster dose of COVID-19 vaccine should be considered for the pediatric population in China. To our knowledge, only a few studies evaluated the VE of mRNA vaccines against the transmission during the period when SARS-CoV-2 Alpha or Delta variants dominated29,30,52, and the investigation of VE of inactivated vaccines against transmission of Omicron subvariants was generally lacking53. Notably, our findings suggested an effective protection against BA.5 transmission within a year conferred by a second dose of inactivated vaccine in children and adolescents, consistent with another finding of lower values of R and SAR estimates for children and adolescents index cases with two-dose vaccine within a year. Furthermore, it appeared that the level of VE against transmission sustained within a year post-vaccination, partly consistent with the finding from large-scale cohort studies suggesting that the protection provided by the vaccine against individual infectiousness was less affected by time54.

Our study had several limitations. First, our estimations of the transmission risk and VE relied heavily on contact tracing data. Thus, any recall bias from the traced cases during the contact tracing process, and the under-ascertainment of case issues would deviate our estimates. Nonetheless, since lockdown and door-to-door mass testing have been rapidly conducted since the very beginning of the local outbreak, the proportion of under-ascertainment cases was assumed to be low. Second, selection bias may affect the VE estimates if there were systematic differences between the two-dose vaccine and reference groups. We partially accounted for this issue by adjusting the estimates with several observable confounders. Nevertheless, limited access to the data restricted us from testing whether children and adolescent or their caregivers in these groups contrast in some unobservable characteristics such as risk perception to infection and compliance to COVID-19 prevention behaviors. The sample size for the analyses of VE was small and may not be representative of the general pediatric population in China and thereby our VE estimates should be interpreted with caution. Our study sample contained all pediatric cases and close contacts identified during the whole course of an Omicron outbreak and we believed that our finding would be especially helpful for the local government and other settings with similar public health capacity. In addition, as we lack data regarding the vaccine brand (Sinopharm or Sinovac) each participant received, we considered two inactivated vaccine brands together in the analysis. Our VE estimates were mostly driven by the Sinopharm vaccine, given that majority of the vaccinees received the Sinopharm vaccine during the study period. Third, since no children and adolescents in our study cohort received a third dose of vaccine, we cannot assess the effectiveness of a booster dose of inactivated vaccine. Furthermore, since we did not have unbiased unvaccinated children and adolescents, we cannot estimate the absolute effectiveness of a two-dose inactivated vaccine. Finally, as the majority of children and adolescent cases included in our study were asymptomatic (89%, 109/122), the estimated VE may be more generalizable to asymptomatic cases. Likewise, as the most of subjects in the 0–12 age group were over 3 years old, our findings for this age group should be interpreted towards those aged 4–12 years.

Conclusions

Our findings demonstrated a moderate transmission risk of children and adolescent cases with the Omicron BA.5 infection, with a higher risk in household settings in the context of stringent PHSMs. Two-dose inactivated vaccine may potentially reduce the risk of transmission. The protective effect of a two-dose inactivated vaccine against all infection and transmission of Omicron BA.5 was high among children and adolescents within a year compared to a one-dose or a two-dose vaccine after a year. These results provide additional evidence concerning the inactivated vaccine to prevent the Omicron BA.5 infection and transmission. Considering the persistently emerging Omicron variants, monitoring the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines is important to inform vaccine rollout among children and adolescents.

Data availability

The anonymized data for generating the tables is available in Supplementary Data 2.

Code availability

Statistical analyses were performed in R (Version 4.1.3). The code is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1051898355.

References

Backer, J. A. et al. Shorter serial intervals in SARS-CoV-2 cases with Omicron BA.1 variant compared with Delta variant, the Netherlands, 13 to 26 December 2021. Euro Surveill. 27, 2200042 (2022).

Liu Y., Rocklöv J. The effective reproductive number of the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 is several times relative to Delta. J. Travel Med. 29, taac037 (2022).

Willett, B. J. et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron is an immune escape variant with an altered cell entry pathway. Nat. Microbiol. 7, 1161–1179 (2022).

Hachmann, N. P. et al. Neutralization escape by SARS-CoV-2 omicron subvariants BA.2.12.1, BA.4, and BA.5. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 86–88 (2022).

WHO. Weekly epidemiological update on COVID-19 - 11 January 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19---11-january-2023 (accessed January 13, 2023).

Valier, M. R. et al. Racial and ethnic differences in COVID-19 vaccination coverage among children and adolescents aged 5-17 years and parental intent to vaccinate their children - National Immunization Survey-child COVID Module, United States, December 2020-September 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly Rep. 72, 1–8 (2023).

Castagnoli, R. et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in children and adolescents: a systematic review: A systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 174, 882–889 (2020).

CDC. For parents: Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) associated with COVID-19. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/mis/mis-c.html (accessed January 13, 2023).

Butt, A. A. et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 disease severity in children infected with the Omicron variant. Clin. Infect. Dis 75, e361–e367 (2022).

Plotkin, S. A. & Levy, O. Considering mandatory vaccination of children for COVID-19. Pediatrics 147, e2021050531 (2021).

Rao, S. et al. Clinical features and burden of postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 176, 1000–1009 (2022).

Chun, J. Y., Jeong, H. & Kim, Y. Identifying susceptibility of children and adolescents to the Omicron variant (B.1.1.529). BMC Med. 20, 451 (2022).

Chen, L.-L. et al. Omicron variant susceptibility to neutralizing antibodies induced in children by natural SARS-CoV-2 infection or COVID-19 vaccine. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 11, 543–547 (2022).

Tan, S. H. X. et al. Effectiveness of BNT162b2 vaccine against omicron in children 5 to 11 years of age. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 525–532 (2022).

Chemaitelly, H. et al. Covid-19 vaccine protection among children and adolescents in Qatar. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 1865–1876 (2022).

Price, A. M. et al. BNT162b2 protection against the omicron variant in children and adolescents. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 1899–1909 (2022).

Klein, N. P. et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 Pfizer-BioNTech BNT162b2 mRNA vaccination in preventing COVID-19-associated emergency department and urgent care encounters and hospitalizations among nonimmunocompromised children and adolescents aged 5-17 years - VISION Network, 10 states, April 2021-January 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly Rep. 71, 352–358 (2022).

Dorabawila, V. et al. Risk of infection and hospitalization among vaccinated and unvaccinated children and adolescents in New York after the emergence of the omicron variant. JAMA 327, 2242–2244 (2022).

Florentino, P. T. V. et al. Vaccine effectiveness of CoronaVac against COVID-19 among children in Brazil during the Omicron period. Nat. Commun. 13, 4756 (2022).

Leung, D. et al. Effectiveness of BNT162b2 and CoronaVac in children and adolescents against SARS-CoV-2 infection during Omicron BA.2 wave in Hong Kong. Commun. Med. 3, 3 (2023).

Jara, A. et al. Effectiveness of CoronaVac in children 3-5 years of age during the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron outbreak in Chile. Nat. Med. 28, 1377–1380 (2022).

González, S. et al. Effectiveness of BBIBP-CorV, BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 vaccines against hospitalisations among children and adolescents during the Omicron outbreak in Argentina: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 13, 100316 (2022).

Castelli, J. M. et al. Effectiveness of mRNA-1273, BNT162b2, and BBIBP-CorV vaccines against infection and mortality in children in Argentina, during predominance of delta and omicron covid-19 variants: test negative, case-control study. BMJ 379, e073070 (2022).

Rosa Duque, J. S. et al. COVID-19 vaccines versus pediatric hospitalization. Cell Rep. Med. 4, 100936 (2023).

Cordery, R. et al. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 by children to contacts in schools and households: a prospective cohort and environmental sampling study in London. Lancet Microbe 3, e814–e823 (2022).

Silverberg, S. L. et al. Child transmission of SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pediatr. 22, 172 (2022).

Zhu, Y. et al. A meta-analysis on the role of children in severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 in household transmission clusters. Clin. Infect. Dis. 72, e1146–e1153 (2021).

Chen, F., Tian, Y., Zhang, L. & Shi, Y. The role of children in household transmission of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 122, 266–275 (2022).

de Gier, B. et al. Vaccine effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 transmission and infections among household and other close contacts of confirmed cases, the Netherlands, February to May 2021. Euro Surveill. 26, 2100640 (2021).

Eyre, D. W. et al. Effect of covid-19 vaccination on transmission of alpha and delta variants. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 744–756 (2022).

Chen S. China approves Covid-19 vaccine for children as young as three. [cited 2023 May 2]. Available at: https://www.scmp.com/news/china/science/article/3136177/china-approves-covid-19-vaccine-children-young-three (2021).

Vadrevu, K. M. et al. Persistence of immunity and impact of third dose of inactivated COVID-19 vaccine against emerging variants. Sci Rep. 12, 12038 (2022).

Li, J. et al. Post-vaccination SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in children aged 3-11 years and the positivity in unvaccinated children: a retrospective, single-center study. Front. Immunol. 13, 1030238 (2022).

Chadeau-Hyam, M. et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccine effectiveness in England (REACT-1): a series of cross-sectional random community surveys. Lancet Respir. Med. 10, 355–366 (2022).

Thompson, H. A. et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) setting-specific transmission rates: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 73, e754–e764 (2021).

Lloyd-Smith, J. O., Schreiber, S. J., Kopp, P. E. & Getz, W. M. Superspreading and the effect of individual variation on disease emergence. Nature 438, 355–359 (2005).

Adam, D. C. et al. Clustering and superspreading potential of SARS-CoV-2 infections in Hong Kong. Nat. Med. 26, 1714–1719 (2020).

Guo, Z. et al. Superspreading potential of infection seeded by the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.1 variant in South Korea. J. Infect. 85, e77–e79 (2022).

Zhao S., Guo Z., Chong M. K. C., He D., Wang M. H. Superspreading potential of SARS-CoV-2 Delta variants under intensive disease control measures in China. J. Travel Med. 29, taac025 (2022).

Jackson, M. L. & Nelson, J. C. The test-negative design for estimating influenza vaccine effectiveness. Vaccine 31, 2165–2168 (2013).

Bond, H. S., Sullivan, S. G. & Cowling, B. J. Regression approaches in the test-negative study design for assessment of influenza vaccine effectiveness. Epidemiol. Infect. 144, 1601–1611 (2016).

Althouse, B. M. et al. Superspreading events in the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2: Opportunities for interventions and control. PLoS Biol. 18, e3000897 (2020).

Davies, N. G., Klepac, P., Liu, Y., Prem, K. & Jit, M. CMMID COVID-19 working group, et al. Age-dependent effects in the transmission and control of COVID-19 epidemics. Nat. Med. 26, 1205–1211 (2020).

Li, X. et al. The role of children in transmission of SARS-CoV-2: a rapid review. J. Glob. Health 10, 011101 (2020).

Sah, P. et al. Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2109229118 (2021).

de Souza, T. H., Nadal, J. A., Nogueira, R. J. N., Pereira, R. M. & Brandão, M. B. Clinical manifestations of children with COVID-19: a systematic review. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 55, 1892–1899 (2020).

Lind, M. L. et al. Evidence of leaky protection following COVID-19 vaccination and SARS-CoV-2 infection in an incarcerated population. Nat. Commun. 14, 5055 (2023).

Premikha, M. et al. Comparative effectiveness of mRNA and inactivated whole-virus vaccines against Coronavirus disease 2019 infection and severe disease in Singapore. Clin. Infect. Dis. 75, 1442–1445 (2022).

Florentino, P. T. V. et al. Vaccine effectiveness of two-dose BNT162b2 against symptomatic and severe COVID-19 among adolescents in Brazil and Scotland over time: a test-negative case-control study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 22, 1577–1586 (2022).

Zhang, H. et al. Inactivated vaccines against SARS-CoV-2: neutralizing antibody titers in vaccine recipients. Front. Microbiol. 13, 816778 (2022).

Wang, H. et al. Humoral and cellular immunity of two-dose inactivated COVID-19 vaccination in Chinese children: a prospective cohort study. J. Med. Virol. 95, e28380 (2023).

Zaidi, A. et al. Effects of second dose of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination on household transmission, England. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 29, 127–132 (2023).

Madewell, Z. J., Yang, Y., Longini, I. M. Jr, Halloran, M. E. & Dean, N. E. Household secondary attack rates of SARS-CoV-2 by variant and vaccination status: An updated systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open. 5, e229317 (2022).

Mongin, D. et al. Effect of SARS-CoV-2 prior infection and mRNA vaccination on contagiousness and susceptibility to infection. Nat. Commun. 14, 5452 (2023).

Guo Z., Zhao S., Wang K. Transmission risks of Omicron BA.5 following inactivated COVID-19 vaccines among children and adolescents in China. GitHub https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10518983 (2023).

Acknowledgements

KW was supported by the youth science and technology innovation talent of Tianshan Talent Training Program in **njiang, China (Grant No.: 2022TSYCCX0099). This study was supported by the 14-th Five-Year Plan Distinctive Program of Public Health and Preventive Medicine in Higher Education Institutions of **njiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China. SZ was supported by Tian** Medical University start-up funding. We thank all participants in this study for their cooperation in disease surveillance and control measure. We also thank healthcare professionals, caregiver partners, and public health practitioners for their contributions to the community.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: S.Z. Methodology: Z.G., and S.Z. Software: Z.G,. and K.W. Validation: T.Z., K.W., and S.Z. Formal analysis: Z.G. Investigation: Z.G., and S.Z. Resources: Y.L., and K.W. Data curation: Z.G., and Y.L. Writing - original draft: Z.G., and S.Z. Writing - review and editing: T.Z., Y.L., S.S., X.L., J.R., Y.W., M.K.C.C., and K.W. Visualization: Z.G., and S.Z. Supervision: K.W., and S.Z. Project administration: Z.G., and T.Z. Funding acquisition: K.W., and S.Z. All authors critically read the manuscript and gave final approval for publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks Rafaella Fortini Grenfell e Queiroz, Feng Sun, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, Z., Zeng, T., Lu, Y. et al. Transmission risks of Omicron BA.5 following inactivated COVID-19 vaccines among children and adolescents in China. Commun Med 4, 92 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-024-00521-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-024-00521-y

- Springer Nature Limited