Abstract

Background

Blood-stained tears can indicate occult malignancy of the lacrimal drainage apparatus. This study reviews data on patients presenting with blood in their tears and the underlying cause for this rare symptom.

Methods

Patients presenting with blood in their tears, identified over a 20-year period, were retrospectively collected from a single tertiary ophthalmic hospital’s database and analysed.

Results

51 patients were identified, the majority female (58%) with a mean age of 55 years. Most cases were unilateral (96%) with blood originating from the nasolacrimal drainage system in 53%. The most common diagnosis for blood-stained tears was a lacrimal sac mucocele (n = 16) followed by a conjunctival vascular lesion (n = 4). Three patients had systemic haematological disorders. The rate of malignancy was 8% (n = 4), with 2 patients having lacrimal sac transitional cell carcinomas, one with a lacrimal sac plasmacytoma and the other with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and bilateral orbital infiltration (with bilateral bloody tears). One patient had a lacrimal sac inverted papilloma, a premalignant lesion. Four patients had benign papillomas (of the lacrimal sac, conjunctiva and caruncle).

Conclusion

Haemolacria was a red flag for malignancy in 8% of patients (and tumours in 18% of patients). A thorough clinical examination including lid eversion identified a conjunctival, caruncle, eyelid or canalicular cause in 27% of cases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Blood-stained tears, or haemolacria, is a rare ophthalmic presenting symptom, and raises the alarming possibility of an underlying malignancy. A history of blood-stained tears, in the absence of obvious recent trauma, surgery or conjunctival disease, triggers Ophthalmologists to investigate for a malignancy of the lacrimal apparatus. These patients are often referred to oculoplastic services to exclude a neoplastic process. However, there are many other non-malignant causes of bloody tears, ranging from disorders of the conjunctiva (e.g., haemorrhagic conjunctivitis), lacrimal gland (e.g., dacryoadenitis), coagulation disorders (e.g., haemophilia or anticoagulation therapy), and trauma.

The literature on the aetiology of haemolacria largely encompasses small numbers of case reports, and thus the incidence of malignant causes, particularly involving the nasolacrimal system, is uncertain. This study collects data on the investigations and diagnoses of patients presenting with blood in their tears in order to identify the true risk of lacrimal tumours and malignancy and identify how these malignant diagnoses were made.

Methods

A retrospective review of case notes was conducted for patients with haemolacria who presented to the lacrimal unit in Moorfields Eye Hospital between 2000 and 2021. A search for key terms on the electronic patient database included ‘haemolacria’, ‘blood-stained tears’, and ‘blood(y) tears’. Case notes were then scrutinised and clinical details were recorded including demographics, clinical assessment, investigations, biopsy results and diagnosis. Patients were telephoned for subjective outcomes and the most recent follow-up data.

Exclusion criteria included children (younger than 16 years old), eviscerated/enucleated sockets, viral conjunctivitis, ophthalmic surgery (ocular, lid, nasolacrimal or orbital surgery) within 2 years of presentation, or trauma.

Data were analysed with SPSS. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (MEH number CA16/AD/25) and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from the patients including informed consent for publication of their images.

Results

Fifty-one patients were identified, with a mean age of 55 years (17–90 years), and a female predominance (58%). Most patients identified as Caucasian (48%) followed by Asian (19%), other (12%), Afro-Caribbean (10%), with 10% being unknown. Most patients were referred to the Moorfields Ophthalmology specialist service via the Ophthalmic Accident and Emergency Department (39%) or their general practitioner (37%).

The majority of patients presented with unilateral symptoms (96%, 49 of 51 cases); the 2 bilateral cases included one subsequently diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) and the other with non-organic/functional symptoms. Patients reported blood-stained tears for an average of 116 days (1–1460 days) prior to presentation. Of the 51 cases, 31% had a singular episode of blood-stained tears and 14% had two episodes. Forty three per cent of patients reported more than 2 episodes and 12% had an unknown number of episodes. Blood-stained tears were positively identified on clinical examination in only 25% of cases (n = 13). Whilst most cases of blood-stained tears were spontaneous, some were triggered by eye rubbing (8%), nose blowing (2%), or contact lens insertion/removal (6%). The most common associated symptoms were epiphora (40%), mucous discharge (31%), epistaxis (12%), medial canthal swelling (10%), periorbital swelling (4%), and pain (4%).

Systemic haematological derangement predisposes to blood-stained tears: 18% (n = 9) of patients were on blood-thinning medications, with 6 on a single anti-platelet agent (aspirin or clopidogrel), 1 on an anticoagulant (apixaban), and 2 on combination therapy. One patient was on aspirin, ibuprofen and ticagrelor. The majority of patients on such medication had concurrent localised ophthalmic disease identified: 6 had lacrimal mucoceles, 1 had a conjunctival vascular lesion and 1 had contact lens related haemolacria. Three patients had haematological abnormalities on further investigation (anaemia and/or thrombocytopenia), and were subsequently diagnosed with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia (CLL), liver cirrhosis, and multiple myeloma. These patients also had concurrent local ophthalmic disease—orbital infiltration, lacrimal mucocele, and a lacrimal sac plasmacytoma respectively.

Most patients underwent lacrimal syringing (78%, n = 40). There were 34 (67%) patients who underwent further diagnostic investigations including radiological imaging, blood tests or biopsy (Table 1). Of those who had no investigations, 7 were conjunctival lesions, 2 had canaliculitis, 1 had contact lens related blood-stained tears, 4 declined investigations, and 3 were lost to follow-up. Twenty-nine patients (57%) underwent Computed Tomography (CT) imaging of the orbits and nasolacrimal system. Dacryocystography (DCG) was undertaken in 15 of the 25 patients with lacrimal sac abnormalities, 6 of which were normal. DCG helped identify lacrimal drainage lesions causing filling defects and nasolacrimal obstruction such as retained lacrimal tubes (Fig. 1). There were 4 patients (8%) who underwent MRI which were all normal and 6% patients had a chest X-ray to assess for granulomatous disease. Blood tests were undertaken in 10 patients (20%). As aforementioned, new haematological abnormalities were found in 3 patients which led to systemic diagnoses of multiple myeloma, CLL, and liver cirrhosis.

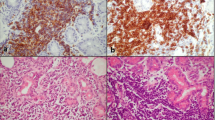

The most common source of blood-stained tears originated from the nasolacrimal system (53%) followed by conjunctival lesions (16%), Table 2. The most common diagnosis was a lacrimal sac mucocele (31%). Six patients had a lacrimal sac/orbital tumour of which 4 patients (8%) had a final biopsy proven diagnosis of malignancy, two with transitional cell carcinomas originating from the lacrimal sac, one lacrimal sac plasmacytoma and one with orbital CLL. Features of lacrimal sac tumours or malignancies included a non-regurgitable/non-compressible medial canthal mass and a sac mass with bony erosion on CT (Fig. 2), with lacrimal sac biopsy securing a diagnosis. These lacrimal sac masses extended above the medial canthal tendon for the 2 transitional cell carcinoma cases. For the patient with orbital CLL infiltration, diagnosis was made based on bilateral periorbital swelling and bruising, subconjunctival haemorrhage, Full Blood Count, bilateral diffuse orbital lesions on CT (Fig. 2), and bone marrow biopsy. There were 2 patients with nasolacrimal drainage system papillomatous lesions. One of which was an inverted papilloma, with the potential to develop into a malignant lesion.

A Right lacrimal sac plasmacytoma (axial). B Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia bilateral orbital infiltration (coronal). C Transitional cell carcinoma of the right lacrimal sac with intrinsic calcified hyperdensities (axial). D Transitional cell carcinoma of the right lacrimal sac (axial). E Inverted papilloma in the left lacrimal sac (axial).

At the time of referral the proportion of patients with a malignancy presenting as blood-stained tears was 8%. Once a conjunctival, eyelid, caruncle or canalicular source was excluded by slit lamp examination and lid eversion such as a vascular lesion (Fig. 3), the likelihood of a malignant diagnosis did not significantly increase (11%). Overall, tumours were identified in a total of 18% of patients (malignant lesions and papillomas of the lacrimal sac, conjunctival, and caruncle).

Patients were followed up for a mean of 24 months (range 1 day to 192 months). There were 4 patients who were deceased at the time of research follow-up, however none of these patients had known malignancy.

Discussion

This is the largest known case series of patients presenting with haemolacria. Blood-stained tears have been associated with infection, inflammation, vascular lesions, systemic bleeding disorders, malignancy, trauma including orbital fractures [1, 2], surgery, foreign bodies, functional/non-organic, or can be idiopathic. The common causes are typically localised to the nasolacrimal drainage system (canaliculitis [3], dacryocystitis, neoplasia, or reflux epistaxis [4,5,6,7]) or conjunctiva (conjunctivitis, vascular lesions, or pyogenic granuloma [3, 8]).

Tumour/malignant causes

Investigation of patients with blood-stained tears revealed 8 tumours, with 4 cases of malignancy and 1 case of a premalignant lesion. Their final diagnoses were lacrimal sac transitional cell carcinomas in two patients, lacrimal sac plasmacytoma from multiple myeloma, CLL with orbital infiltration and inverted papilloma of the lacrimal sac. Although malignancy within this cohort was only 8%, nevertheless a thorough investigation of bloody tears remains essential. As suspected, the most common anatomical location of the blood in those with malignancy was the lacrimal sac. The rate of malignancy increased to 50% in patients with bilateral blood-stained tears. However, it was much less commonly bilateral, and only occurred in 2 patients.

The three patients with lacrimal sac malignancies all had visible and palpable lacrimal sac masses that were non-compressible. They all showed complete nasolacrimal duct blockage on lacrimal irrigation, 2 showed blood in the regurgitated irrigation fluid, and none had reflux of pus. They all had a mass on CT with adjacent bony erosion. All underwent lacrimal sac biopsies to reveal their diagnoses. It is reported that a lacrimal sac mass extending above the medial canthal tendon is a risk factor for a malignant sac lesion, this occurring in 2 of the 3 lacrimal sac malignancies in this series. This alone is an indication for radiological investigation with CT or MRI [9]. The patient in this series with orbital infiltration from CLL had bilateral blood-stained tears. His blood tests revealed the clue to his underlying systemic malignancy which was confirmed with a bone marrow biopsy.

Similar to this study, Azari et al. described haemaolacria from a transitional cell carcinoma of the lacrimal sac [10]. Others have described it arising from lacrimal sac melanoma [11, 12] and lymphoma/reactive lymphoid hyperplasia [13]. Less common benign lesions of the lacrimal sac such as inflammatory polyps [14], pyogenic granuloma [15], lymphangioma [16] and varices [17] have also been published. Rare lacrimal sac infections such as rhinosporidiosis [18] can also present with haemolacria, but as they can mimic malignancy, biopsy is still warranted.

Eyelid, conjunctiva, caruncle and canalicular causes

Clinically, this study shows the importance of a thorough slit lamp examination and eversion of the eyelids. This approach will identify the source of haemolacria in over a quarter of patients (14, 27%) with the origins including eyelid, conjunctiva, caruncle and canaliculi. Other than lacrimal irrigation, these patients do not require further investigation.

Conjunctival pathologies associated with haemolacria include injuries, infection, inflammation (such as giant papillary conjunctivitis) [19], pyogenic granuloma, and vascular lesions. Conjunctival or lacrimal gland vascular lesions reported in the literature include hemangioma [20,21,22,23,24], varix, and telangiectasia (isolated or hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia [25, 26]). Rarely, conjunctival malignancy is implicated such as melanoma [27].

At the lid margin, blepharoconjunctivitis and crab lice infestation have also been implicated [28].

Orbital pathologies including vascular lesions [29], scleral buckles [30], and orbital fracture implants [1] have also been associated with blood-stained tears.

Lacrimal sac mucocele

Amongst our cohort of 51 patients, lacrimal sac mucocele was the most common cause of blood-stained tears, occurring in almost a third of patients (16, 31%). In contrast to patients with malignant lacrimal sac lesions, mucous regurgitation followed syringing in the majority of mucocele cases (11, 69%). Blood was seen in the irrigation fluid of 3 mucocele cases (19%) which was similar to the malignant lacrimal sac lesion group.

In regards to the nasolacrimal system, nasolacrimal obstruction with dacryocystitis is the most common cause of haemolacria. Retained lacrimal stents, whole or otherwise, are also reported in such patients [31]. In this series, 2 individuals presented with retained stent segments up to 2.5 years after surgery, presumably due to partial ‘notching’ of the stent at surgery with subsequent breakage prior to removal.

Lacrimal sac papilloma

Lacrimal sac papillomas are a commonly reported cause of haemolacria. Inverted papilloma has a malignant potential in 5–15% of cases with a high recurrence rate [32], and prompt diagnosis and complete excision of the lacrimal sac and nasolacrimal duct are recommended.

Our study shows that a DCG can be beneficial in identifying lacrimal drainage aetiology, particularly retained foreign bodies (Fig. 1a), nasolacrimal duct obstruction, and filling defects due to lacrimal sac masses (Fig. 1b).

Haematological disorders

Haematological disorders predispose to bloody tears in the context of concurrent ophthalmic disease such as minor trauma, dacryocystitis, or surgery [1]. These include coagulation factor deficiencies, haemophilia, thrombocytopenic purpura, and vasculitides such as Henoch-Schonlein purpura [33, 34]. Investigations including haemaglobin level, platelet count, coagulation tests, coagulation factors and genetic mutations can help screen for such disorders, and are especially important for bilateral cases. Conditions with indirect or incompletely understood effects on coagulation have also been associated with bloody tears including hyperthyroidism (causing platelet abnormalities and hyperdynamic state) [35], ‘vicarious menses,’ [2] and trigemino-autonomic headache [36]. Bloody tears during menstruation is termed vicarious menses and the aetiology is theorised to be ectopic endometrial tissue or premenstrual hypertension.

Functional haemolacria

Our single case of functional, or ‘idiopathic’ haemolacria is not isolated, with several such reports in the literature, and the diagnosis is one of exclusion [2, 35, 37, 38]. Psychogenic causes due to conversion disorder, Munchausen syndrome, and malingering are also diagnoses of exclusion. A patient in our study complained of blood from the eyes, ears and nose, but this was never witnessed. Serial clinical exams were unremarkable and investigations (blood tests, CT and MRI) were normal. Self-induced trauma or the use of chemicals/liquids have also been reported to masquerade as haemolacria [2]. In these situations thorough investigation is required to be reassured as clinicians that there is no true organic course, which might have a distracting functional overlay.

Limitations

The limitations of this study include limited follow-up duration and a small patient cohort. Some diagnoses were unknown as patients declined further investigations or did not attend further follow-up.

Conclusion

This is the largest known study and literature review on haemolacria. It demonstrates that haemolacria is a true red flag for tumour or malignancy, particularly in the nasolacrimal system. Although rates of malignancy are low at 8% (tumours 18%), identifying these patients early can positively impact on their life expectancy and treatment options. A thorough clinical assessment including lid eversion should be performed to exclude a conjunctival, eyelid, caruncle or canalicular cause. If no cause is identified on examination, then lacrimal syringing should be performed. If the examination is clear, blood-stained tears are identified on nasolacrimal duct irrigation, or a lacrimal sac mass is palpated, then further radiological imaging ± biopsy is required for a diagnosis. Blood tests are useful to identify systemic haematological anomalies that predispose to bleeding, especially in bilateral cases.

Summary

-

This is the largest study focussing on blood stained tears.

-

Blood stained tears is a red flag for malignancy and the rate of malignancy in our cohort was 8%.

-

Majority of the malignancies originated from the lacrimal sac.

-

Clinical examination including lid eversion is essential as it identified 27% of causes, originating from the conjunctiva, eyelid, canaliculus or caruncle.

-

If an ocular surface lesion has been excluded, then further investigation is recommended including imaging, bloods, and/or biopsy.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient confidentiality but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chon BH, Zhang R, Bardenstein DS, Coffey M, Collins AC. Bloody Epiphora (Hemolacria) years after repair of orbital floor fracture. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;33:e118–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/IOP.0000000000000839.

Murube J. Bloody tears: historical review and report of a new case. Ocul Surf. 2011;9:117–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1542-0124(11)70021-0.

Singh CN, Thakker M, Sires BS. Pyogenic granuloma associated with chronic Actinomyces canaliculitis. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;22:224–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.iop.0000214529.43021.f4.

Garcia GA, Bair H, Charlson ES, Egbert JE. Crying blood: association of valsalva and hemolacria. Orbit. 2021;40:266. https://doi.org/10.1080/01676830.2020.1768562.

Wiese MF. Bloody tears, and more! An unusual case of epistaxis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87:1051. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.87.8.1051.

Banta RG, Seltzer JL. Bloody tears from epistaxis through the nasolacrimal duct. Am J Ophthalmol. 1973;75:726–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9394(73)90829-5.

Wieser S. Bloody tears. Emerg Med J. 2012;29:286. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2011-200955.

Sen DK. Granuloma pyogenicum of the palpebral conjunctiva. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1982;19:112–4.

Vahdani K, Gupta T, Verity DH, Rose GE. Extension of masses involving the lacrimal sac to above the medial canthal tendon. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;37:556–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/IOP.0000000000001946.

Azari AA, Kanavi MR, Saipe N, Lee V, Lucarelli M, Potter HD, et al. Transitional cell carcinoma of the lacrimal sac presenting with bloody tears. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131:689–90. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.2907.

Zhu LJ, Zhu Y, Hao SC, Huang P, Wang LL, Li XH, et al. Clinical experience on diagnosis and treatment for malignancy originating from the dacryocyst. Eye. 2018;32:1519–22. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-018-0132-1.

Li YJ, Zhu SJ, Yan H, Han J, Wang D, Xu S. Primary malignant melanoma of the lacrimal sac. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2012-006349.

Wolf EJ, Wessel MM, Hirsch MD, Leib ML. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the nasolacrimal duct presenting as bloody epiphora. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;23:242–3. https://doi.org/10.1097/IOP.0b013e31803ecf11.

Demir HD, Aydın E, Koseoğlu RD. A lacrimal sac mass with bloody discharge. Orbit. 2012;31:179–80. https://doi.org/10.3109/01676830.2011.648812.

Yazici B, Ayvaz AT, Aker S. Pyogenic granuloma of the lacrimal sac. Int Ophthalmol. 2009;29:57–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10792-007-9168-0.

Li E, Yoda RA, Keene CD, Moe KS, Chambers C, Zhang MM. Nasolacrimal lymphangioma presenting with hemolacria. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;36:e118–22. https://doi.org/10.1097/IOP.0000000000001622.

Lee H, Herreid PA, Sires BS. Bloody epiphora secondary to a lacrimal sac varix. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;29:e135–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/IOP.0b013e318281eca0.

Belliveau MJ, Strube YN, Dexter DF, Kratky V. Bloody tears from lacrimal sac rhinosporidiosis. Can J Ophthalmol. 2012;47:e23–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjo.2012.03.019.

Eiferman RA. Bloody tears. Am J Ophthalmol. 1982;93:524–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9394(82)90147-7.

Di Maria A, Famà F. Hemolacria—crying blood. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1766. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMicm1805241.

Maxted G. Pedunculated haemangeioma of conjunctiva. Br J Ophthalmol. 1919;3:429–30. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.3.9.429.

Legrand J, Hervouet F, Loue J. Case of dacryohemorrhysis. Bull Soc Ophtalmol Fr. 1976;76:307–8.

Bakker A. A MYXO-HAEMANGIOMA SIMPLEX OF THE CONJUNCTIVA BULBI. Br J Ophthalmol. 1948;32:485–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.32.8.485.

Yazici B, Ucan G, Adim SB. Cavernous hemangioma of the conjunctiva: case report. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;27:e27–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/IOP.0b013e3181c4e3bf.

Krohel GB, Duke MA, Mehu M. Bloody tears associated with familial telangiectasis. Case Rep Arch Ophthalmol. 1987;105:1489–90. https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.1987.01060110035020.

Soong HK, Pollock DA. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia diagnosed by the ophthalmologist. Cornea. 2000;19:849–50. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003226-200011000-00017.

Rodriguez ME, Burris CK, Kauh CY, Potter HD. A conjunctival melanoma causing bloody tears. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;33:e77. https://doi.org/10.1097/IOP.0000000000000765.

BELAU PG, RUCKER CW. Bloody tears: report of case. Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin. 1961;36:234–8.

Bonavolontà G, Sammartino A. Bloody tears from an orbital varix. Ophthalmologica. 1981;182:5–6. https://doi.org/10.1159/000309082.

Mukkamala K, Gentile RC, Rao L, Sidoti PA. Recurrent hemolacria: a sign of scleral buckle infection. Retina. 2010;30:1250–3. https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181d2f15e.

Kemp PS, Allen RC. Bloody tears and recurrent nasolacrimal duct obstruction due to a retained silicone stent. J AAPOS. 2014;18:285–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaapos.2013.12.011.

Sbrana MF, Borges RFR, Pinna FR, Neto DB, Voegels RL. Sinonasal inverted papilloma: rate of recurrence and malignant transformation in 44 operated patients. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;87:80–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjorl.2019.07.003.

Gião Antunes AS, Peixe B, Guerreiro H. Hematidrosis, hemolacria, and gastrointestinal bleeding. GE Port J Gastroenterol. 2017;24:301–4. https://doi.org/10.1159/000461591.

Siggers DC. Bloodstained tears. Br Med J. 1970;4:177. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.4.5728.177-b.

Ho VH, Wilson MW, Linder JS, Fleming JC, Haik BG. Bloody tears of unknown cause: case series and review of the literature. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;20:442–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.iop.0000143713.01616.cf.

Silva GS, Nemoto P, Monzillo PH. Bloody tears, gardner-diamond syndrome, and trigemino-autonomic headache. Headache. 2014;54:153–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.12226.

Fowler BT, Kosko MG, Pegram TA, Haik BG, Fleming JC, Oester AE. Haemolacria: a novel approach to lesion localization. Orbit. 2015;34:309–13. https://doi.org/10.3109/01676830.2015.1078371.

Beyazyıldız E, Özdamar Y, Beyazyıldız Ö, Yerli H. Idiopathic bilateral bloody tearing. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med. 2015;2015:692382. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/692382.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and/or designed the work that led to the submission, acquired data, and/or played an important role in interpreting the results—MK, VJ, DGE, DHV, JU, HT. Drafted or revised the paper—MK, VJ, DGE, DHV, JU, HT. Approved the final version—MK, VJ, DGE, DHV, JU, HT. Agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved—MK, VJ, DGE, DHV, JU, HT. As corresponding author, MK, confirms that she has had full access to the data in the study and final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kaushik, M., Juniat, V., Ezra, D.G. et al. Blood-stained tears—a red flag for malignancy?. Eye 37, 1711–1716 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-022-02224-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-022-02224-x

- Springer Nature Limited