Abstract

Background

Child stunting, child underweight, and child wasting in Nepal decreased from 48%, 47%, and 11% to 25%, 19%, and 9%, respectively, between 1996 and 2022. Despite an overall reduction in prevalence rates, economically poor and geographically backward regions in Nepal have not seen equivalent improvement in child undernutrition similar to their richer and developed regions, leading to increased differences in undernutrition prevalence across the wealth quintiles. This study aimed to assess time trends in the average and inequality of child nutritional status by household wealth across Nepal's geographical spaces from 1996 to 2022.

Methods

This study utilized data from four rounds (1996, 2006, 2016, and 2022) of the Nepal Demographics and Health Survey (NDHS). The nutritional status of children below three years of age, measured by stunting, wasting, and underweight, served as the main dependent variable. Household wealth status, determined by binary responses regarding possession of household assets, acted as a proxy for economic status. The study employed point prevalence for average, Concentration Index (CI), Poorest-Richest-Ratio (P-R-R), and Poorer-Richer-Ratio (Pr-Rr-R) to analyze trends in child nutritional status by wealth quintiles.

Results

From 1996 to 2022, Nepal exhibited an increasing Concentration Index and an upward trend in P-R-R measures of inequality in child stunting. The P-R-R increased from 1.77 in 1996 to 2.51 in 2022, However, results show a concurrent decrease in Pr-Rr-R from 1.19 to 1.18, assessing the prevalence of stunting among children. In the prevalence of child underweight, the P-R-R and Pr-Rr-R were 1.88 and 1.19 in 1996, decreasing to 1.47 and 1.10, respectively, in 2022.

Conclusion

The results indicated that inequalities in child nutrition across wealth status show an increase in stunting but marginal decline in underweight and wasting. Therefore, the study underscores the need for inclusive policy and program interventions to achieve equitable improvement in child stunting in Nepal, ensuring that progress extends to children in the poorest wealth quintile households. However, the progress is equitable in child underweight and wasting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Background

Globally, approximately 150 million children under five years old were stunted in 2017, with over half (55%) of them located in Asia [1, 2]. Between 2000 and 2019, the region achieved significant advancements in decreasing child undernutrition, evidenced by a 34 million decrease in the number of stunted children in the region. [1,2,3]. However, the 2020 Global Nutrition Report indicated discouraging progress in global nutrition improvement [4]. Progress towards Sustainable Development Goal-2 (SDG) targets related to child stunting, wasting, and underweight was insufficient and unequal [5]. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic presented challenges in accessing affordable and safe food, as well as essential health and nutritional services, leading to increased economic inequality [6,7,8,9].

Since the early nineteenth century, industrialized nations maintained a tradition of monitoring socioeconomic inequalities and implementing corresponding policies [10]. Despite efforts to reduce socioeconomic inequalities in health, develo** countries only recently (after publications of Black report during 1980s) recognized these disparities. The policy focus was primarily on overall health progress, overlooking acknowledged social injustice [10,11,12,13,14,15,16].

The World Health Organization (WHO) report indicated that social disparities notably influenced premature mortality, slow growth, and health advancement [17]. Political, historical, socioeconomic inequality, and public health policies hinder individuals from achieving good health despite its inherent possibility [18,19,20,21,22,23]. Tracking progress in average health status and social inequality is vital for achieving SDGs targets [24]. The present study examines trends in average versus inequality in child undernutrition in Nepal. The subsequent sections present a brief overview of the country context, theoretical underpinning, and research gap. Section 4 delineates survey data, sampling techniques, and empirical methodology. Section 5 presents empirical analysis results, followed by a comprehensive discussion in Sect. 6 Lastly, Sect. 7 provides conclusions and policy implications.

2 Country context

Nepal, situated in South Asia, grappled with persistent challenges related to poverty and food insecurity. The recent report, "Nepal Multidimensional Poverty Index: Analysis Towards Action," unveiled that 4.9 million people, constituting 17.4% of the population, remained in the grip of multidimensional poverty [25, 26]. Over 80% (24.5 million) of the population struggled to afford a healthy diet. Additionally, approximately 8% of the population, equivalent to 11 million people, faced moderate to severe food insecurity [25]. The report highlighted that 18% of children aged 6 to 23 months did not receive meals at the recommended frequency, only 48% received a minimum acceptable diet, and 57% could not access meals with a minimum dietary diversity [27].

Nepal faced challenges, including natural disasters, inadequate infrastructure, urbanization, emigration, the feminization of agriculture, and unstable food prices [26, 28]. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated these challenges by disrupting supply chains, threatening small enterprises, and rendering individuals highly susceptible to falling back into poverty due to widespread income and job losses [25, 26].

Nevertheless, Nepal made noteworthy strides in reducing child undernutrition, nearly achieving the Millennium Development Goal objective of halving the prevalence of child underweight from 1990 to 2022 [29, 30]. Progress was evident in pursuing Sustainable Development Goal targets for child overweight, stunting, and wasting [4, 31]. Child stunting prevalence in Nepal witnessed a substantial decline from 57.1% in 2001 to 25% in 2022. However, despite improvement, this percentage remained unacceptably high. The wasting rate decreased from 11.3% in 2001 to 8% in 2022, and child underweight decreased from 43 to 19% from 2001 to 2022 [25].

Despite a decrease in prevalence rates, child undernutrition persisted more in economically poor and geographically backward regions, contributing to heightened difference in undernutrition prevalence among poorest and richest children [32,33,34].

3 Theoretical underpinnings and research gap

The link between health inequalities and average per capita income is heavily influenced by the strength and nature of the relationship between economic growth and technological advancement [35,36,37,38]. More affluent individuals typically have access to and adopt new and improved technologies before their less affluent counterparts do, resulting in a greater realisation of economic benefits [38]. As a result, when the overall health status of a population improves, it benefits the richer individuals disproportionately more, which exacerbates health inequalities [24, 35,36,37,38,39,40,41].

Over time, as technological innovations become more widely available, the gap in health status between the rich and poor will eventually begin to narrow. This is because the less affluent members of society will adopt the new technologies as well, until they catch up to their more affluent counterparts. However, this process is not automatic, as not all societies are equally prepared for technological innovation and adoption. As a result, health inequalities may persist until the less affluent members of society are able to adopt the new technologies and catch up to the more affluent members [42].

Panayotov [43] proposed an empirical framework that explains the mechanism responsible for the increase in health disparities despite the general enhancement in health conditions [43]. The framework delineates the correlation between average health status (AHS) and health inequalities (HI) under different conditions. Panayotov suggests that better overall health may conceal growing health inequalities. When health gain and health equity are independent of each other, they satisfy the Kaldor-HicksFootnote 1 efficiency criterion. This framework offers a comprehensive understanding of the correlation between health status and health disparities, which is vital for policymakers to develop efficient health interventions.

The relationship between average health status (AHS) and health inequality (HI) is dynamic and contingent upon the economic distribution of benefits. The association curve is dynamic and subject to change due to policy initiatives and interventions. Policy interventions are crucial in determining the distribution of economic benefits among various demographic groups. Panayotov (2008) has categorised eight distinct combinations of relationships between AHS and HI, while imposing an additional constraint of temporal constancy for both variables. Four conditions are classified as "major" due to alterations in both AHS and HI, while the remaining four are labelled as "minor" due to changes in either AHS or HI alone (see Fig. 1). The combinations of major changes are as follows;

-

1)

Increase in AHS and HI (Red Line).

-

2)

Increase in AHS and decrease in HI (Green Line).

-

3)

Decrease in AHS and increase in HI (Black Line, Left and Up).

-

4)

Decrease in AHS and decrease in HI (Dashed Black Line, Left and Down).

Panayotov's theoretical framework explains the correlation between income growth and health disparities. Early adoption of health technologies by affluent and healthy individuals can exacerbate health inequalities first followed by decline in inequality in condition of sustained pace of progress and continued policy efforts. The issue arises when the affluent and healthier population begin to shape policy in a manner that primarily benefits them, leading to further concentration of resources among the affluent and an increase in the gap between the affluent and less affluent. A strong pro-poor policy is necessary to achieve inclusive and pro-poor growth in this situation.

However, the previous studies have mainly focused on either the average health status or health inequalities separately, when investigating the health transition among wealthy and poor countries [14, 15, 19, 44, 45]. Therefore, further research is required to investigate the correlation between income growth and health disparities, taking into account both average health status and health inequalities concurrently. Some studies have explored these topics for health status and nutritional status [35, 36, 39, 40, 46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57]. However, a limited research has examined the correlation between average trends and disparities in child nutritional status in Nepal [32, 56,57,58,59,60,61,62]. The variation in nutritional status and socioeconomic inequality over time and across regions is a matter of concern [59] because the benefits of MSNP nutritional interventions in Nepal are not evenly distributed across rural, urban, ecological and developmental regions [32].

Achieving holistic and sustainable nutritional transition across the socioeconomic strata is foremost important to achieve the SDGs goals. In order to evaluate the relationship between "average health status and health inequalities, this study will use data on the nutritional status (stunting, wasting and underweight) of children below three year of age across the geographical, ecological and developmental regions of Nepal from the year 1996–2022. Furthermore, the present study utilised Mackenbach and Kunst's [57] analytical frameworks to measure socioeconomic inequalities in nutritional status. The study employs both relative and absolute measures of inequality to evaluate whether the inequality in child undernutrition are ‘swimming against the tide’ [63]. Therefore, the study's findings will aid policymakers in develo** strategies and interventions to combat the increasing economic inequality in child undernutrition (specially stunting) across various regions of Nepal.

4 Methods and materials

4.1 Data and sample

This study utilized unit-level data from the Nepal Demographic and Health Survey conducted in 1996, 2006, 2016, and 2022 (NDHS-1996, NDHS-2006, and NDHS-2016, NDHS-2022). The NDHS is a standardized survey program conducted in over 90 countries, with more than 300 surveys since its inception. It is part of the larger Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) program, employing standardized questions and methods to gather data across nations. The survey aims to collect information on various indicators related to fertility, mortality, family planning, reproductive health, household characteristics, marital status, maternal and child health, nutrition status, child immunizations, and HIV/AIDS. Targeting women aged 15–49, respondents were selected based on identification within chosen households using household and individual questionnaires. Data, categorized into individual (women), household, kids, couple, men, and member files, was utilized for tabulation. This study employed data from the children's file of four rounds of NDHS. Before 2006, anthropometric data was collected for children under three years, and since then, data collection expanded to include children under five years.

The study used nutritional status of children under three, assessing weight-for-age, weight-for-height, and weight-for-age measurements below two standard deviations from the WHO reference population, classifying as stunted, wasted, and underweight, respectively [64]. By adhering to these standards, the study ensures alignment with global data, enabling a more thorough analysis of child malnutrition trends in Nepal and facilitating comparisons on a global scale. Household asset holding served as a proxy for economic status, derived using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on binary response variables of household assets, following Rustein & Johnson (2004) [65,66,67].

4.2 Sampling

The NDHS obtained data using a multi-stage stratified cluster probability sampling method. The most recent sampling frame, considering evolving rural/urban classification, divided areas into wards with data on location, residence type, estimated household size, and population. The sample, stratified into two stages for rural and three for urban areas in Nepal, selected approximately 30 households per cluster with equal probability. Non-proportional sample allocation necessitated sampling weights to ensure representative estimates across regions. Eligible respondents were women aged 15–49 who were either permanent residents. No provisions allowed replacing pre-selected respondents or households. Consent was obtained for data and biomarker collection from a subset of households [27].

4.3 Variable definition and empirical strategy

This study used point prevalence to estimate stunting, wasting, and underweight prevalence in children under three for 1996, 2006, 2016 and 2022. Economic inequality in child nutritional indicators was assessed in rural, urban, and ecological zones over 26 years. A chi-square test determined the statistical significance of the bivariate analysis of household wealth status and child nutritional status. Relative and absolute measures of inequality, including the Poorest-Richest-Ratio (P-R-R) and Poorer-Richer-Ratio (Pr-Rr-R) methodology, were employed to evaluate the distribution of improvements in child nutritional status among wealth quintiles. Following Mackenbach & Kunst framework, a ratio value of unity indicated comparable nutritional status experiences. A value above 1 suggested less nutritional deficiency in wealthier households, while below 1 indicated lower malnutrition burden among the poorest households' children. Absolute inequality measures, including the Concentration Index (CI) developed by Wagstaff & colleagues [13], were also employed.

4.3.1 Concentration index (CIs)

The concentration index is used for the measurement of economic inequality in child under nutritional status across the geographical places of Nepal. The concentration index is calculated as the product of a person's relative economic position and the (weighted) covariance of the health variables, divided by the variable mean.

where, \(\upmu\) is the (weighted) mean of the nutrition variable of the sample and \({{\text{cov}}}_{{\text{w}}}\) denotes the weighted covariance, and Yi and Ri are, nutritional status and fractional rank of ith individual for weighted data in terms of the index of household economic status. The estimated values of the concentration index ranges from -1- to + 1. The negative extreme value (−1) suggest that the concentration is more among the poor household/individual and positive extreme (+ 1) suggest that the concentration is more among the rich household/individuals. The third extreme value (0) suggests that there is no concentration among the wealth status of household/individual, the point of no inequality.

5 Results

5.1 Trends and geographical differentials in Stunting, Underweight and Wasting among children

The study observed a significant reduction in child stunting over the past 26 years. Stunting prevalence in children under 3 years old dropped from about 50% in 1996 to 25% in 2022. The decline accelerated from 2006 to 2022 compared to the period from 1996 to 2006. Child underweight decreased from 47% in 1996 to 35% in 2006 and further to 20% in 2022. Wasting in children under three years decreased from 11.3% in 1996 to 8.9% in 2022.

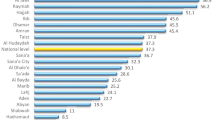

Significant variations in malnutrition prevalence and reduction were evident across geographic regions. Urban Nepal saw a large stunting decrease from 35% in 1996 to 22% in 2022, while rural areas saw a larger decrease from about 50–29%. In 1996, urban underweight prevalence was 30%, contrasting with 48% in rural areas. By 2022, rural areas experienced a more substantial decline in underweight prevalence. Wasting increased in urban areas but decreased in rural areas from 1996 to 2022 (Table 1).

Child malnutrition estimates varied across ecological regions in Nepal. Stunting was more prevalent in the mountain region (57%) than in the Hill (49%) and Tarai (47%) regions in 1996 but decreased to 33%, 20%, and 26%, respectively, in 2022. The prevalence of underweight decreased everywhere from 1996 to 17% in Mountain, 12% in Hill, and 24% in Tarai regions in 2022. The study period revealed a slight decrease (1%) in wasting prevalence in the Tarai region and a 50% reduction in the Mountain and Hill regions (Table 2).

5.2 Trend of child malnutrition prevalence by economic status

The study noted a decline in child malnutrition rates over time. However, children in the poorest wealth quintiles experienced higher malnutrition rates compared to wealthier children. In 1996, stunting prevalence in the wealthiest quintile was 33%, while in the poorest quintiles, it was nearly 60%. Stunting decreased significantly from 1996 to 2022 across all economic strata, with the wealthiest quintiles exhibiting a more rapid decline. Contrary to conventional nutritional growth trajectories, the results indicate an opposite trend of inequality decline. When the intervention took place the malnutrition prevalence decreases more among population with highest prevalence as compared to their counterparts.

In 1996, underweight prevalence was higher in children from the poorest quintile (53%) compared to the richest quintile (28%). In 2022, underweight was prevalent among 20% of children from the poorest quintile and 14% from the richest quintile. However, the rate and magnitude of decline were higher in the poorest groups than the richest groups in child underweight. In 1996, wasting prevalence was 13% in the poorest quintile and 5% in the richest quintile. In 2022, wasting prevalence increased among the richest children and slightly declined among the poorest children (Table 3).

5.3 Trends of economic inequality in child malnutrition

The study revealed a significant decrease in child nutritional status, with 23% points decline in the poorest quintile and a 19% decline in the richest quintile in child stunting from 1996 to 2022. Similar patterns of inequality were observed for underweight, with a 33% decline among the poorest and a 15% decline in the richest quintile. The overall findings indicated significantly greater levels of child malnutrition among children from the poorest quintile compared to those in the richest quintile but higher rate of decline in poorest quintile than richest quintile children.

The study assessed inequality trends through Poorest-Richest-Ratio (P-R-R), Poorer-Richer-Ratio (Pr-Rr-R), and Concentration Index (CI). From 1996 to 2022, Nepal showed an improvement in inequality in malnutrition across economic quintiles, although the differences were still large. The P-R-R and Pr-Rr-R rose for stunting but showed a marginal decline for underweight and wasting. The chi-square test indicated significant economic disparities in child stunting for all survey years but insignificant disparities for underweight and wasting in 2022.

Absolute inequality measured through CI in stunting showed a considerable increase from 2006 to 2022. Underweight and wasting exhibited a considerable increase from 1996 to 2006 but a slight decrease in 2022 (Table 3).

5.4 Rural Urban differentials in nutritional inequality

Relying solely on national-level inequality trends might lead to a misleading understanding of inequality. Geographical location and place of residence exhibited significant variation in economic inequality concerning child undernutrition. The study on economic disparities found that in rural areas, the P-R-R for stunting increased significantly from 1.69, 1.17 in 1996 to 4.14, 1.37 respectively in 2016 and then declined to 2.15, 1.32 respectively in 2022 (Table 4).

Relative inequality measured through P-R-R and Pr-Rr-R in stunting increased over the study period in rural areas. Child stunting in rural areas showed an increase in CI values from -0.0818 to -0.1058 between 1996 and 2022. Absolute inequality measured through Concentration Index for urban areas also indicated a significant rise between 1996 and 2022 in child stunting.

The P-R-R, Pr-Rr-R for child underweight increased or remained constant between 1996 and 2016 in urban areas but showed a reduction in absolute inequality across rural residences in Nepal (Table 5). Relative inequality measures for child wasting decreased in both urban and rural areas. However, the Pr-Rr-R measure showed a decrease in economic inequality in child wasting in rural areas, while there was a slight increase in urban areas during the study period (Table 6).

5.5 Ecological differentials in nutritional inequality

Tables 7 presented the P-R-R, Pr-Rr-R, and CI in the prevalence of stunted, underweight, and wasted children in Nepal for 1996, 2006, 2016, and 2022. The data categorized children based on ecological regions and household economic status. The study revealed a rise in nutritional inequality by economic status when measuring absolute inequality (CI) among children in mountain regions. Relative inequality, measured through Pr-Rr-R in child stunting, showed a greater decline among children from wealthy households compared to those from impoverished households from 1996 to 2016 in the mountain region. The Pr-Rr-R in the prevalence of underweight increased from 1.03 in 1996 to 2.26 in 2006. Similarly, absolute inequality in child underweight increased over the study period. Inability to calculate the richest/poorest ratio for 2016 was due to limited sample size of undernourished children from both higher and lower economic statuses. Relative inequality also rose from 1996 to 2006 for wasting in the mountain region but declined in absolute inequality from 1996 to 2022 in this region.

Relative inequality, measured through P-R-R and Pr-Rr-R in stunting, showed sustained increase from 1996 to 2016 in hilly regions. Child underweight and wasting exhibited declining trends in relative inequality in P-R-R but increasing trends in Pr-Rr-R. Furthermore, the Tarai regions showed a trend of increasing relative inequality in child stunting and underweight. Relative inequality in child wasting showed marginal decline in P-R-R and Pr-Rr-R in Tarai regions of Nepal. The concentration index for stunting and underweight increased over time, indicating a rise in absolute inequality in these indicators in Nepal's mountain regions but a declining inequality in child wasting. Absolute inequality in hilly regions increased for child stunting and underweight but marginally declined for child wasting. Tarai regions also showed substantial increase in absolute inequality in child malnutrition measured through stunting and underweight but decline in child wasting over the years. Despite a significant decrease in undernutrition prevalence across ecological locations, there is a growing trend of inequality in child stunting. The highest relative inequality in child stunting, underweight, and wasting is in the Tarai region. The highest absolute inequality is in the hilly region for child stunting and in the mountain region for child underweight.

6 Discussion

Nepal underwent political and economic instability from 1996 to 2022 due to various challenges such as armed conflict, government instability, a major earthquake, an economic blockade, and a transition to a new federal governance system [68,69,70]. Despite these obstacles, Nepal achieved notable advancements in maternal and child nutrition indicators [62, 71]. However, disparities persisted during sustained improvements in nutritional status. Our analysis, which examined trends in average nutritional status across economic status and geographical locations in Nepal, showed that the wealth quintile differentials are declining but still large. The study revealed a growing disparity in child undernutrition occurrence among households with varying wealth levels, in both absolute and relative inequality measures. The affluent population showed a more significant and faster decline in child stunting compared to the less affluent population.

. Health interventions initially favored the wealthy, leading to higher absolute disparities in child stunting which reduces ultimately through policy intervention for economically weaker children [24, 41, 42, 72]. The study emphasized monitoring progress in both average and inequality for informed decision-making regarding policy effectiveness and ensuring that no one is left behind [3, 38, 73, 74]. Concentration index analyses also revealed a considerable increase in economic inequality in child stunting over time, aligning with patterns observed in other studies from the region [31, 32, 59, 61, 62]. However, the positive sign of inequality reduction is also highlighted by the decline in underweight and wasting differentials across the wealth status over the time span.

The study highlighted a significant reduction in child underweight in Nepal over the past two decades, with underweight being more prevalent in rural Tarai regions. Relative inequality indices for underweight decreased over time, indicating a decline in economic inequality across Nepal during 1996–2022. Wasting showed a declining trend over the years across wealth quintiles. Despite these wealth disparity in child undernutrition prevalence, average child nutritional indicators continued to improve, consistent with previous research on the relationship between health inequalities and average health status [35,36,37,38,39,40].

Various factors contributed to growing economic disparities in child malnutrition within Nepal, including insufficient healthcare access and quality, inadequate safe water and sanitation, limited availability of nutritious food, higher birth order, and maternal short stature. Additionally, determinants like poverty, agricultural backwardness, social protection, lower maternal education, limited women empowerment, and regional concentration of undernutrition played significant roles [9, 29, 60, 61, 75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87].

Nutrition-sensitive interventions targeting underlying determinants of malnutrition, such as poverty, integrating nutrition counseling into maternal and child health and family planning programs, and evaluating the cost-effectiveness of social safety net programs are crucial [62, 75, 76, 82, 88]. The study emphasized that despite successful progress in improving average nutritional status, pro-poor aspects of nutritional transition need more attention for child stunting [9, 32, 33, 89]. The Multi-Sectoral Nutrition Plan (MSNP), initiated in 2013, expanded its reach and maintained its strategy, contributing to noticeable improvement in economic inequality in child wasting and underweight in 2022. However, challenges such as insufficient nutrition capacity hindered MSNP expansion [90]. The MNSP (2018–2022) aimed at achieving national and global nutrition targets within the context of the new federalist governance structure, with supplementary policies like the National Nutrition Policy (NNP), School Nutrition and Meals Programme (SNMP), and Vitamin A and Deworming Campaigns [91].

The study recommended targeted program and policy interventions in subnational regions with prevalent inequality conditions, sustaining momentum, and accelerating efforts to attain the nutritional targets of SDG 2 along with equity.

7 Conclusion and policy implications of the study

In Nepal, there were significant advancements in reducing the average undernutrition for children over the last 26 years. However, there were still worrisome geographical disparities in undernutrition, especially stunting and underweight based on economic status. The presence of inequalities in undernutrition was influenced by various factors, including health system functions like fertility control and maternal health improvement, education, maternal height, and asset-based wealth distribution. This study investigated child undernutrition in Nepal and revealed that despite governmental attempts to reduce the rich-poor gap in child stunting, disparities intensified between 1996 and 2022. The prevalence of undernutrition was more prevalent among low-income families, irrespective of geographical location. The study indicated that decreasing the mean undernutrition prevalence may not have effectively tackled the socioeconomic disparities in child undernutrition. Therefore, tailored policy interventions targeting undernutrition indicators, inequality patterns and prioritizing the most disadvantaged and vulnerable groups may have helped reverse these trends and address inequality. Furthermore, a comprehensive approach involving multiple sectors was required to effectively tackle both nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive programs. This entailed implementing social protection measures for economically disadvantaged individuals. Therefore, the translation of political commitments into comprehensive programs and policies was crucial for enhancing not only the mean nutritional status but also for achieving a significant reduction in nutritional disparities across different economic and geographical strata.

8 Limitation of the study

The study is based on cross-sectional data, which poses limitations for establishing causation. Additionally, the definition and relevance of wealth items present challenges, as items such as bicycles and radios may become outdated and unnecessary over time. Moreover, the study lacks comprehensive wealth values for all household items, making it difficult to accurately assess wealth differentials. Merely recording "yes" or "no" responses for wealth items does not capture the nuances of wealth distribution. Furthermore, the study fails to elucidate the reasons behind the increasing prevalence of wasting among children in richer households. Discrepancies between various measures also complicate the interpretation of changes in underweight and wasting. The future study should try to address these issues to make a story line for nutrition transition in Nepal.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated or analysed during the current study are freely available in public domain and can be accessed from the Official website of DHS, website (https://ihds.umd.edu/about/citing-ihds). However the data files will be provided upon request.

Notes

A method of evaluating economic resource redistributions among individuals, known as the "Kaldor-Hicks criterion," captures some of the intuitive appeal of Pareto improvements but has softer requirements and is thus applicable to a wider range of situations. A re-allocation is a Kaldor-Hicks improvement if it could theoretically result in a Pareto-improving outcome and those who benefit compensate those who suffer. A Kaldor-Hicks improvement can actually make some people's situation worse because the compensation does not necessarily have to happen (there is no presumption in favour of the status quo) (Kaldor and Hicks, 1939)”.

Abbreviations

- NDHS:

-

Nepal demographics and health survey

- CI:

-

Concentration Index

- P-R-R:

-

Poorest-richest-ratio

- Pr-Rr-R:

-

Poorer-richer-ratio

- SDG:

-

Sustainable development goals

- WHO:

-

World Health Organisation

- AHS:

-

Average health status

- HI:

-

Health inequalities

- PCA:

-

Principle component analysis

- PSUs:

-

Primary sampling units

- MSNP:

-

Multi-sectoral nutrition plan

- CMAM:

-

Community-based management of acute malnutrition

- NNP:

-

National nutrition policy

- SNMP:

-

School nutrition and meals programme

References

Torlesse H, Aguayo VM. Aiming higher for maternal and child nutrition in South Asia. Matern Child Nutr. 2018;14:e12739.

UNICEF.WHO, & World Bank Group. 2020. UNICEF/WHO/The World Bank Group joint child malnutrition estimates: levels and trends in child malnutrition: Key findings of the 2020 edition. ISBN: 9789240003576

UNICEF (2018). The State of The World's Children. Growing well in a changing world. https://www.unicef.org/media/60811/file/SOWC-2019-Exec-summary.pdf.

Development Initiatives (2020) Global nutrition report: action on equity to end malnutrition. Development Initiatives, Bristol. https://globalnutritionreport.org/reports/2020-global-nutrition-report/

Katoch OR. Tackling child malnutrition and food security: assessing progress, challenges, and policies in achieving SDG 2 in India. Nutr Food Sci. 2024;54(2):349–65. https://doi.org/10.1108/NFS-03-2023-0055.

Fore HH, Dongyu Q, Beasley DM, Ghebreyesus TA. Child malnutrition and COVID-19: the time to act is now. Lancet. 2020;396(10250):517–8.

Fore HH. A wake-up call: COVID-19 and its impact on children’s health and wellbeing. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(7):e861–2.

Headey D, Heidkamp R, Osendarp S, Ruel M, Scott N, Black R, Walker N. Impacts of COVID-19 on childhood malnutrition and nutrition-related mortality. Lancet. 2020;396(10250):519–21.

Acosta AM, Fanzo J. Fighting maternal and child malnutrition: analysing the political and institutional determinants of delivering a national multisectoral response in six countries. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies; 2012.

Goli S, Arokiasamy P. Demographic transition in India: an evolutionary interpretation of population and health trends using ‘change-point analysis.’ PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):e76404.

Drever, F., & Whitehead, M. (Eds.). (1997). Health inequalities: decennial supplement. Stationery Office.

Acheson D, Barker D, Chambers J, Graham H, Marmot M, Whitehead M. (1998). Independent inquiry into inequalities in health. London: The Stationery Office. [Google Scholar]

Wagstaff A, Paci P, Van Doorslaer E. On the measurement of inequalities in health. Soc Sci Med. 1991;33(5):545–57.

Kakwani N, Wagstaff A, Van Doorslaer E. Socioeconomic inequalities in health: measurement, computation, and statistical inference. J Econ. 1997;77(1):87–103.

Gwatkin DR. Health inequalities and the health of the poor: what do we know? What can we do? Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78:3–18.

Hosseinpoor AR, Van Doorslaer E, Speybroeck N, Naghavi M, Mohammad K, Majdzadeh R, Vega J. Decomposing socioeconomic inequality in infant mortality in Iran. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(5):1211–9.

World Health Organization. Inequities are killing people on grand scale. Geneva: Report of WHO; 2008.

Wagstaff A, Watanabe N. Socioeconomic inequalities in child malnutrition in the develo** world. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper. 2000.

Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Almeida-Filho N. A glossary for health inequalities. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56(9):647–52.

Wagstaff A, Van Doorslaer E, Watanabe N. On decomposing the causes of health sector inequalities with an application to malnutrition inequalities in Vietnam. J Econ. 2003;112(1):207–23.

Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet. 2005;365(9464):1099–104.

Deaton A. The great escape. The Great Escape: Princeton University Press; 2013.

Katoch OR. Determinants of malnutrition among children: a systematic review. Nutrition. 2022;96(2022):111565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2021.111565.

Jamison DT, Summers LH, Alleyne G, Arrow KJ, Berkley S, Binagwaho A, Yamey G. Global health 2035: a world converging within a generation. Lancet. 2013;382(9908):1898–955.

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023. Urbanization, agrifood systems transformation and healthy diets across the rural–urban continuum. Rome: FAO; 2023.

National Planning Commission (2021). Nepal multidimensional poverty index: analysis towards action. https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/migration/np/UNDP-NP-MPI-Report-2021

Ministry of Health and Population [Nepal], New ERA, and ICF. Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2022. Kathmandu, Nepal: Ministry of Health and Population [Nepal]; 2023.

Tamang S, Paudel KP, Shrestha KK. Feminization of agriculture and its implications for food security in rural Nepal. J Forest Livelihood. 2014;12(1):20–32.

National Planning Commission [Government of Nepal]. Nepal and the millennium development goals: final status report 2000–2015. Kathmandu: National Planning Commission; 2016.

National Planning Commission [Government of Nepal] (2016). Fourteen Development Plan (2016/17–2018/19) Kathmandu. Nepal.

Headey D, Hoddinott J, Ali D, Tesfaye R, Dereje M. The other Asian enigma: explaining the rapid reduction of undernutrition in Bangladesh. World Dev. 2015;66:749–61.

Angdembe MR, Dulal BP, Bhattarai K, Karn S. Trends and predictors of inequality in childhood stunting in Nepal from 1996 to 2016. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18:1–17.

Krishna A, Mejía-Guevara I, McGovern M, Aguayo VM, Subramanian SV. Trends in inequalities in child stunting in South Asia. Matern Child Nutr. 2018;14:e12517.

Devkota MD, Adhikari RK, Upreti SR. Stunting in Nepal: looking back, looking ahead. Matern Child Nutr. 2016;12(Suppl 1):257.

Wagstaff A. Inequalities in health in develo** countries: swimming against the tide?, vol. 2795. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Publications; 2002.

Wagstaff A. Inequality aversion, health inequalities and health achievement. J Health Econ. 2002;21(4):627–41.

Moser KA, Leon DA, Gwatkin DR. How does progress towards the child mortality millennium development goal affect inequalities between the poorest and least poor? Analysis of demographic and health survey data. BMJ. 2005;331(7526):1180–2.

Goli S, Arokiasamy P. Trends in health and health inequalities among major states of India: assessing progress through convergence models. Health Econ Policy Law. 2014;9(2):143–68.

Contoyannis P, Forster M. The distribution of health and income: a theoretical framework. J Health Econ. 1999;18(5):605–22.

Victora CG, Vaughan JP, Barros FC, Silva AC, Tomasi E. Explaining trends in inequities: evidence from Brazilian child health studies. Lancet. 2000;356(9235):1093–8.

Dorius SF. Global demographic convergence? A reconsideration of changing intercountry inequality in fertility. Popul Dev Rev. 2008;34(3):519–37.

Vallin J, Meslé F. Convergences and divergences in mortality: a new approach of health transition. Demogr Res. 2004;2:11–44.

Panayotov J. Evidence in public health and health impact assessment. Sci Med. 2008;33:545–57.

Subramanyam MA, Subramanian SV. Research on social inequalities in health in India. Indian J Med Res. 2011;133(5):461.

Tonoyan T, Muradyan L. Health inequalities in Armenia-analysis of survey results. Int J Equity Health. 2012;11(1):1–12.

Zere E, McIntyre D. Inequities in under-five child malnutrition in South Africa. Int J Equity Health. 2003;2(1):1–10.

Sen, A., & Himanshu. (2004). Poverty and Inequality in India-I. Economic and Political Weekly, 39(38) :4247–63. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4415560

Pathak PK, Singh A. Trends in malnutrition among children in India: growing inequalities across different economic groups. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(4):576–85.

Carr D. (2008). Improving the health of the world’s poorest people overcoming the curse of malnutrition in India: a leadership agenda for action.

Pande RP, Yazbeck AS. What’s in a country average? Wealth, gender, and regional inequalities in immunization in India. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(11):2075–88.

Van de Poel E, Hosseinpoor AR, Speybroeck N, Van Ourti T, Vega J. Socioeconomic inequality in malnutrition in develo** countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86(4):282–91.

Grantham-McGregor S, Cheung YB, Cueto S, Glewwe P, Richter L, Strupp B. Developmental potential in the first 5 years for children in develo** countries. Lancet. 2007;369(9555):60–70.

Gwatkin DR, Rutstein S, Johnson K, Suliman E, Wagstaff A, Amouzou A. Socio-economic differences in health, nutrition, and population. Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2007. p. 1–301.

Houweling TA, Kunst AE, Mackenbach JP. Measuring health inequality among children in develo** countries: does the choice of the indicator of economic status matter? Int J Equity Health. 2003;2(1):1–12.

Mackenbach JP, Kunst AE. Measuring the magnitude of socio-economic inequalities in health: an overview of available measures illustrated with two examples from Europe. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(6):757–71.

Pun K, Villa K, Fontenla M. The impact of Nepal’s earthquake on the health status of rural children. Rev Dev Econ. 2023;27(2):710–34.

Sarkar B, Mitchell E, Frisbie S, Grigg L, Adhikari S, Maskey Byanju R. Drinking water quality and public health in the Kathmandu Valley, Nepal: coliform bacteria, chemical contaminants, and health status of consumers. J Environ Public Health. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/3895859.

Bhusal UP, Sapkota VP. Socioeconomic and demographic correlates of child nutritional status in Nepal: an investigation of heterogeneous effects using quantile regression. Glob Health. 2022;18(1):1–13.

Nepali S, Simkhada P, Davies I. Trends and inequalities in stunting in Nepal: a secondary data analysis of four Nepal demographic health surveys from 2001 to 2016. BMC nutrition. 2019;5(1):1–10.

Tiwari R, Ausman LM, Agho KE. Determinants of stunting and severe stunting among under-fives: evidence from the 2011 Nepal Demographic and Health Survey. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:1–15.

Headey D, Hoddinott J, Park S. Drivers of nutritional change in four South Asian countries: a dynamic observational analysis. Matern Child Nutr. 2016;12:210–8.

Headey DD, Hoddinott J. Understanding the rapid reduction of undernutrition in Nepal, 2001–2011. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(12):e0145738.

Wagstaff A, Doorslaer EV. Overall versus socioeconomic health inequality: a measurement framework and two empirical illustrations. Health Econ. 2004;13(3):297–301.

World Health Organization (WHO). Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group. WHO child growth standards: length/height-for age, weight-for-age, weight for length, weight for height: Methods and development. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. p. 312.

Filmer, Deon. (2000). The Structure of Social Disparities in Education : Gender and Wealth. Policy Research Working Paper;No. 2268. World Bank, Washington, DC. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/18813

Filmer D, Pritchett LH. Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data—or tears: an application to educational enrollments in states of India. Demography. 2001;38(1):115–32.

Rustein SO, Johnson K. The DHS wealth index, comparative reports number 6. Calverton, MA: ORC Macro; 2004.

Brøgger DR, Agergaard J. The migration–urbanisation nexus in Nepal’s exceptional urban transformation. Popul Space Place. 2019;25(8):e2264.

Wagle UR, Devkota S. The impact of foreign remittances on poverty in Nepal: a panel study of household survey data, 1996–2011. World Dev. 2018;110:38–50.

World Bank. World development report 2020: trading for development in the age of global value chains. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank; 2019.

Cunningham K, Headey D, Singh A, Karmacharya C, Rana PP. Maternal and child nutrition in Nepal: examining drivers of progress from the mid-1990s to 2010s. Glob Food Sec. 2017;13:30–7.

Victora CG, Joseph G, Silva IC, Maia FS, Vaughan JP, Barros FC, Barros AJ. The inverse equity hypothesis: analyses of institutional deliveries in 286 national surveys. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(4):464–71.

Goli S, Siddiqui MZ. Rise and fall of between-state inequalities in demographic progress in India: application of inequality life cycle hypothesis. Soc Sci Spectrum. 2015;1(3):167–80.

Siddiqui MZ, Goli S, Rammohan A. Testing the regional Convergence Hypothesis for the progress in health status in India during 1980–2015. J Biosoc Sci. 2021;53(3):379–95.

Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP, Bhutta ZA, Christian P, De Onis M, Uauy R. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2013;382(9890):427–51.

Ruel MT, Alderman H. Nutrition-sensitive interventions and programmes: how can they help to accelerate progress in improving maternal and child nutrition? Lancet. 2013;382(9891):536–51.

Central Bureau of Statistics, Government of Nepal. (2012). Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commission Secretariat. https://www.Central Bureau of Statistics.gov.np.

Ministry of Health and Population [Nepal]. Mind the gap: policy brief. Kathmandu: Ministry of Health and Population; 2018.

Uematsu H, Shidiq AR, Tiwari S. Trends and Drivers of Poverty Reduction in Nepal A Historical Perspective. Washington D.C.: World Bank Group; 2016.

Lagarde M, Haines A, Palmer N. Conditional cash transfers for improving uptake of health interventions in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. JAMA. 2007;298(16):1900–10.

Grosh M, Del Ninno C, Tesliuc E, Ouerghi A. For protection and promotion: the design and implementation of effective safety nets. Washington D.C.: World Bank Publications; 2008.

Leroy JL, Gadsden P, Rodriguez-Ramirez S, De Cossío TG. Cash and in-kind transfers in poor rural communities in Mexico increase household fruit, vegetable, and micronutrient consumption but also lead to excess energy consumption. J Nutr. 2010;140(3):612–7.

Kumar A, Kumari D, Singh A. Increasing socioeconomic inequality in childhood undernutrition in urban India: trends between 1992–93, 1998–99 and 2005–06. Health Policy Plan. 2015;30(8):1003–16.

Rabbani A, Khan A, Yusuf S, Adams A. Trends and determinants of inequities in childhood stunting in Bangladesh from 1996/7 to 2014. Int J Equity In Health. 2016;15(1):1–14.

Huda TM, Hayes A, El Arifeen S, Dibley MJ. Social determinants of inequalities in child undernutrition in Bangladesh: a decomposition analysis. Matern Child Nutr. 2018;14(1):e12440.

Aslam M, Kingdon GG. Parental education and child health—understanding the pathways of impact in Pakistan. World Dev. 2012;40(10):2014–32.

Miller JE, Rodgers YV. Mother’s education and children’s nutritional status: new evidence from Cambodia. Asian Dev Rev. 2009;26(1):131–65.

Acharya S, Sharma S, Dulal B, Aryal K. Quality of care and client satisfaction with maternal health services in Nepal: further analysis of the 2015 Nepal Health Facility Survey. DHS Further Analysis Reports No. 112. Rockville. Maryland, USA: ICF; 2018.

Conway, L. G., III, Woodard, S. R., & Zubrod, A. (2020, April 7). Social Psychological Measurements of COVID-19: Coronavirus Perceived Threat, Government Response, Impacts, and Experiences Questionnaires. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/z2x9a

Shrimpton R, Hughes R, Recine E, Mason JB, Sanders D, Marks GC, Margetts B. Nutrition capacity development: a practice framework. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17(3):682–8.

Ministry of Health and Population, Nepal. Multi-sectoral nutrition plan (2013–2017). Kathmandu: Government of Nepal; 2017.

Acknowledgements

The Authors would like thank Prof. Srinivas Goli for providing the conceptual clarity on this issue.

Funding

Not applicable. The paper is an independent work of authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MZS, AI, VA and KN conceptualized the manuscript. MZS and KN performed the analysis and interpretation of the results. AI, MZS, VA, and KN drafted the manuscript. AI, MZS provided critical revision for analysis and manuscript. VA, AI, MZS and KN has done final proofreading and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Present study uses the dataset available in public domain as a part of authors independent research work. Thus, there is no need to seek a separate ethical clearance for this study.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable for this manuscript.

Competing interests

Authors declare no competing interests. All authors read and approved the paper. *We will submit authors form once the paper is accepted for the publication.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Siddiqui, M.Z., Illiyan, A., Akram, V. et al. Revisiting swimming against tide; inequalities in child malnutrition in Nepal. Discov glob soc 2, 26 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44282-024-00047-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44282-024-00047-7