Abstract

The paper's objective is to study one of the world´s early living civilizations, i.e., India, focusing primarily on its rich ancient philosophy with specific reference to holistic education to understand how it may act as a prototype for target 4.7 of the Sustainable Development Goals. The study uses Interpretive sociology to understand the meanings contextually from the insider's perspective. Extensive and intensive usage of symbolism in Indian philosophy is studied through social constructionism and phenomenology. India’s ancient philosophy on holistic education has a relevance to modern approaches to address sustainability issues such as by addressing specific aspects of the SDGs, or the SDGs holistically, given the goals interconnects, and potential synergies and trade-offs, thereby serving as a prototype for target 4.7 of SDG 4. The findings also revel a lack of connection to higher power of spirituality. The originality of the study is the effort enabling comparative analysis across contexts, by placing the SDGs in the context of India’s ancient philosophy on holistic education, befitting the expectations of SDGs, specifically target 4.7. Authors are aware of the tendency of the “book view” (Indological Approach) to homogenize but this is in tune with the papers objective as the intention is to draw an ideal–typical proto-type of holistic education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The world is witnessing massive environmental and societal changes that are impacting human and non-human species, societies, and ecosystems and will continue to do so for a long time to come. Of “nine planetary boundaries within which humanity can continue to develop and thrive for generations to come” six have already been crossed [1, 2]. According to the doughnut economy perspective, the societal and economic aspects are added, claiming that humanity should be within defined boundaries of social foundations, and ecological ceiling, as that is the “safe and just space for humanity” where it can thrive [3], p. 4,2017). This is not the case given the multiple crises addressed in the Paris Agreement and the [4]Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs) [5, 6]. Generally, the SDGs are presented as a set of 17 goals, with 169 targets and an indicator framework including 231 indicators aimed at actions [7] “to end poverty and inequality, protect the planet, and ensure that all people enjoy health, justice and prosperity” within the targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [8, 9]. These global goals have also been presented in a “wedding cake model”, where four of the goals are relevant to biosphere, serving as the cake’s foundation for eight goals relevant to the society, and four that are pertinent to the economy. Goal 17, partnership for the goals, then connects the parts of the model together [10]. Pope Francis [11], in his Encyclical Letter Laudato si’ [Ls] on care for our Common Home, has tied spirituality to sustainability through the seven Laudato Si’ goals which are 1) Responses to the Cry of the Earth, 2) Responses to Cry of the Poor, 3) Ecological Economics, 4) Adoption of Sustainable Lifestyles, 5) Ecological Education, 6) Ecological Spirituality, and 7) Community Resilience and Empowerment [12]. The call for a rescue plan for people and the planet is getting constantly louder, and in this context education plays a crucial role [6]. The idea about spirituality and the SDGs has also been presented in a framework showing how being spiritual influences the cycle between well-being and sustainability [13].

Every society has some essential normative orientations or ideologies that lay down the foundational structure on which the societies ‘ought to be’ built. These include the fundamental ontological perspective/s or philosophies which in the case of India began as oral transmission of lived experiences from one generation to another. Later, these were written down as non-technical narratives, in the Epics, justifying and lending support and coherence to the foundational oral philosophical ontologies. Honward [14] argues that this orally transmitted indigenous knowledge specific to certain communities develops into systems over time, and reflects the ties between social, cultural, and ecological systems [15]. French philosopher Michel Foucault [16] in his work introduces the concept of ‘episteme’ as unconscious rules that determine the social observances, conventions, and the possibility of discourses. Though he treated this concept as a purely Western sixteenth century phenomenon, if we eliminate the specificity of geography and historicity, the concept fits well into the current context of the paper. Consciously carved ontologies in India, over time, have indeed evolved into everyday life as unconscious rules, governing all forms of knowledge.

Though these ideologies have been assembled over time and space by individual members of the society they have acquired power beyond the individual members. Relevant epistemological perspectives evolve to theorize, conceptualize, and explain social reality as it exists at the empirical level. In societies, like India, where the collective is or is intended to be given primacy over the individuals, Western scholarship, devoid of the involvement of emic categories and indigenous intellectual traditions, wrongly misconstrued [17] such a social reality as ‘hyperreality’ [18]. In India, given the vast landscape and consequent heterogeneity, coherent symbols or sets of signifiers were created to build an orderly systematic normative arrangement. The idea of multiple identities like territoriality, religious denominations, gastronomical peculiarities, etc. were addressed by a unique philosophical orientation, and subsequent signifiers and symbols were selected, socially stamped, and presented as a significant part of the socialization process across multiple identities [19, 20].

According to the functionalist perspective, for any society to sustain, a minimalistic integration among the parts is a primary prerequisite. Almost every biological need has a corresponding cultural response. Contextually speaking, to hunger, there are three broad cultural categories of food in India, Sattvic, Rajasic, and Tamasic, which are associated with specific ideologies and modes of being. Stability at the Cultural (symbolic) system level, is ensured by establishing symbols that provide information necessary for co-existence with the environment. This includes not just the physical and tangible environment but also the array of uncertainties caused by the sudden occurrence of illnesses, disease, death, etc. in the passage of life of an individual. These appear in the ancient Indian texts as verses (mantras), such as the Gāyatrī Mantra (Rig Veda, 3.62.10) which offers salutations to the Sun, and the Mahāmṛtyuṃjaya Mantra (Rig Veda, 7.59.12) which asks for liberation or Moksha from the anxiety of disease and death. These symbols also provide a sense of oneness or what Malinowski calls, ‘communal rhythm’ in everyday life [21]. Daily chanting of such like verses helps in the internalization of normative ideologies, and this is superimposed by recurrent collective chanting. This becomes an instrument of asserting social harmony over individual differences.

In the background of the above, the objective of the paper is to understand the philosophical structuring and its role in curating a model for holistic education which can be recurrated for the globe as a prototype for target 4.7 of the Sustainable Development Goals.

The structure of the paper is such that it first provides a theoretical background for the analysis and then discusses Indigenous Knowledge Systems and Holistic Education. This is followed by detailed discussion about the periods of development of ancient Indian philosophy, teaching and learning in ancient Indian context including the teacher-student relationship and the pedagogy, four stages of human life, the ideas of non-duality and the world being one unit, respect for resources, the skill to remain focused, yog and its forms, four fundamentals of ‘ideal’ life, and finally the significance of peace. This is followed by discussions and conclusions sections.

2 Theoretical background

As mentioned earlier, the study uses Interpretive sociology to understand the meanings underlying subjective experiences, belief systems, and practices, from the standpoint of the involved social participants and social institutions. Social constructionism, phenomenology, and interpretative understanding [22] is used to understand how the idea of sustainability is closely tied to the human mind and experience in the ancient philosophy. This has helped us in comprehending how reality is made meaningful through collective participation. Through social constructionism, the intensive symbolism deployed in ancient Indian philosophy is studied. Phenomenology has been used to perceive social responses to the physical reality.

This study involves ethnographic observation and qualitative content analysis [23] using an interpretivist (theoretical) perspective [22]. The founding father of this perspective, Max Weber, argues that only when a behaviour is invested with meaning, does it constitute an action and when intersubjectivities are involved, such an action becomes social action [24]. For the current study, we have primarily focused on, the relevant Upaniṣads and the Bhagavadgītā [25], to grasp the sustainable social and cultural semantics behind the uninterrupted continuity of the Indian civilization. The original reference texts (both the Upaniṣads and the Bhagavadgītā), are in Sanskrit language. For this study, we have relied on several of their English translations [26,27,28,29,30] to comprehend the unique learning, institutionalized by focusing on the human mind and experiential erudition, with an emphasis on the idea of sustainability. Weber´s conceptual category of ‘ideal types’ [24] has been used not as an absolute explanatory tool but to evolve model/s for sustainable education, and for education that can advance sustainability. As Weber suggests, ideal type is being constructed as an “emergency safe haven(s) until one has learned to find one´s bearings while navigating the immense sea of empirical facts” [31], p. 133). It has primarily been used as a comparative tool to shape the empirical reality. Authors are conscious of the cautioned by Weber that the usage of this “conceptual accentuation” [31], p. 124) is heuristic.

3 Indigenous knowledge systems and holistic education

Education, across the globally diverse political, economic, and cultural systems, plays a significant role in ensuring a sustainable life. The word 'Education' itself includes some of the essential elements such as Equity, Development, Universality, Compassionate virtues, Acceptance, Training, Inclusivity, Opportunities for All, and Nurturing, all of which play a significant role in strengthening the foundational integrity of ‘sustainability’. Unfortunately, amidst the global pursuits, some of these essentials have been reduced to mere agendas. This compromised, ‘bandaged approach’ compelled the [4]to adopt a common set of goals with ‘sustainability’ as the prime agenda. The purpose was to set forth a “universal call for action to end poverty, protect the planet and improve the lives and prospects of everyone, everywhere”. However, “action to meet the Goals is not yet advancing at the speed or scale required” [4]. This calls for conscious deterministic efforts to look into ancient philosophical structures which have successfully sustained their respective civilizations for a significant period and can be adopted as models across the globe.

Education is addressed in one of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals stating that “inclusive and equitable quality education” should be ensured and “lifelong learning opportunities for all” promoted. Furthermore, by the end of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development commitment period all learners should “acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including, among others, through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development (Target 4.7)” [4, 32].

This requires a holistic educational approach in the case of philosophical focus and pedagogical methods employed, as it addresses needs of different learners, fosters a connections or wholeness between parts in a person’s life or relationships, considering life experiences and cultures and known and unknown aspects of life [33]. Wholeness and connectedness are thus relevant to a person, a community, a society, and the planet, and the cosmos, resulting in a cosmic harmony, or “ultimacy” [33], p. 183). Holistic education is, furthermore, expressed in the following key principles [33], pp. 183–184), representing a “profound respect for the deeper, largely unrealized power of human nature [34], p. 2)”:

-

1.

Educating for Human Development.

-

2.

Honoring Students as Individuals.

-

3.

The Central Role of Experience.

-

4.

Wholeness of the educational process.

-

5.

New Role of Educators.

-

6.

Freedom of Choice.

-

7.

Educating for a Participatory Democracy.

-

8.

Educating for Global Citizenship.

-

9.

Educating for Earth Literacy.

-

10.

Spirituality and Education.

Indigenous Peoples, who lacked the idea of boundaries of statehood or specificities of nationhood, were the first to educate holistically with the focus on interconnectedness and holistic knowledge [34]. They intricately weave subjectivity into their lives vis-a-vis the territory they live on; people, animals, and trees they live with; natural phenomenon they experience, etc. They associate meanings or symbolisms with everything that concerns them and indulge in meaningful engagements with them. For instance, worship** trees as providers of food, shelter, and even medical care, ensured forest preservation. Source of all meanings and values, especially among the indigenous people, because of the intimacy of interaction, lie in and derive from, the experiences with the world in which they live [35]. Such knowledge has been popularly categorized either as indigenous or traditional, given the historicity and the locale of its origin. It includes a vast landscape of systematic beliefs, practices which over time have manifested themselves as cultural arrangements with structural modalities. Through inter-generational socialization, they are passed down from one generation to another, rendering unique identities to their respective communities [36, 37]. This knowledge also contains elements of “technical knowledge and know-how, agricultural knowledge, and astronomy” [38]. Thus traditional or Indigenous knowledge (IK) is a “unique, traditional, local knowledge existing within, and developed around the specific conditions of women and men indigenous to a geographic area” [39], p. 1,[40], p. 211). Consequently, holistic education, and Indigenous and traditional knowledge are intrinsically and deeply interconnected.

4 Periods of development of ancient indian philosophy

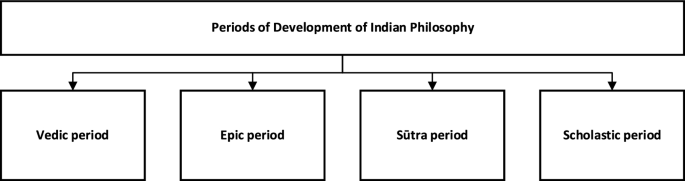

Indian philosophy can be broadly divided into four major periods of development: Vedic period (between 2500 and 600 B.C.E), Epic period (approximately from 500 or 600 B.C.E to A.D. 200), Sūtra period (approximately from the early centuries of the Christian era); and Scholastic period (from the Sūtra period to the 17thc), see Fig. 1.

4.1 The vedic period

The root word of Veda is ‘vid’, (when roughly translated to English, it could mean, ‘to know’ or ‘to understand’). ‘Vid’ is also the root word of vidya, the closest equivalent of this in English would be ‘knowledge’. However, it is important for the readers to know that vidya is much deeper, holistic, and because of its undefined vastness, carries an element of sanctity (and maybe mystery). In fact, if placed on a continuum, it is closer to the English word ‘wisdom’ and has been popularly referred to as jñāna in the Indian philosophy. The feature of ‘sanctity’ makes it superior to the other mundane categories or contexts of knowledge, and thus worthy of preservation by compliance and practice (preservation by perpetuation).

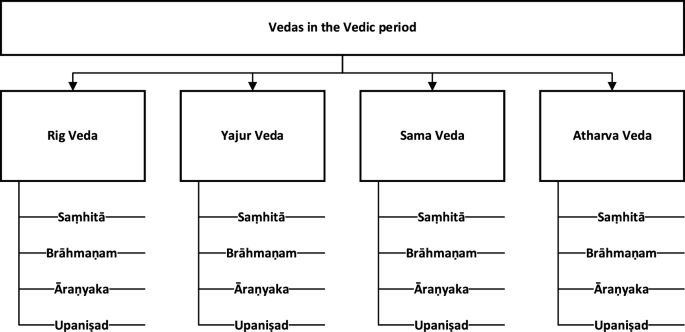

The Vedic period is characterized by four Vedas, i.e. Rig, Yajur, Sama, and Atharva [41], see Fig. 2. Out of these Rig Veda is the oldest, dating 500 CE. Yajur Veda is associated with most of the Principal Upaniṣads and is subdivided into Krishna Yajurveda and Shukla Yajurveda [42]. The origins of Indian classical music, dance, and theatre can be traced to Samaveda, while Atharvaveda lays down nuances of everyday life. Each of the four Vedas is divided into four sections, i.e., Saṃhitā, Brāhmaṇam, Āraṇyaka, and Upaniṣad.

Vedas are anonymous works, believed to have been revealed to deeply focused sages over years of meditation and deep contemplation. These revelations, for almost 2000 years, were transmitted orally and are a part of the ‘heard literature’ (Śrutis) of India. It was around 1500 BCE (Before the Common Era) that a sage named Vyasa compiled it together. Vedas provide a discerning study about the various facets of existence and provide deep insights about several dimensions of sustainability.

The core of the Vedas is scripted in its last section, called the Upaniṣad (also referred to as Vedānta). Though there is no proof of the exact number of Upaniṣads, but there is almost a consensus on them running in 100s [28]. The teachings from the Upaniṣad have deeply influenced Indian social institutions, including education.

None of these teachings/learnings were meticulously drafted like systematic and sequential chapters in a book. As mentioned earlier, these were revelations and thus appear as random pieces of wisdom, beyond the fetters of temporality or space. These were experienced learnings, to be learned by experience and passed from one generation to another. In this background, the teacher in the Indian philosophy appears as someone who is highly experienced and has the skill to equip the student to understand the experience [43]. This shall be discussed in greater details later.

4.2 The Epic period

The Epic period is characterized by the indirect presentation of philosophical doctrines through the medium of nontechnical narrative literature such as the Rāmāyaṇa, the Mahābhārata, and the Bhagavadgītā. Unlike the Vedas, epics are the ‘remembered’ literature (Smṛti), authored from what was seen, experienced, understood, and remembered. The Bhagavadgītā presents ancient Indian philosophy in its applied form, thus making it a popular narrative not just in India but across the globe.

4.3 The Sūtra period

The Sūtra period is the next phase in Indian philosophy in which nine different perspectives or schools were developed. These are: Samkhya, Yog, Vaisesika, Nyaya, Mimamsa, Vedanta (Uttara Mimamsa), Carvaka, Jain, and Buddhists. Out of these, the first six believed in the Vedas and accepted them as a valid means of knowledge while the last three rejected the Vedas. Despite the different foundations, all the nine schools have the same objective or pursuit: balanced endurance of suffering and accepting it as an inescapable reality.

4.4 The scholastic period

Since the Sūtras were written as maxims and were difficult to comprehend, elaborate commentaries were written for better comprehension in the Scholastic Period. These commentaries added fresh interpretations to the existing understanding, thereby making the document alive and fertile. However, it is important to note that these interpretations carried author-specific biases inviting gender and caste-based discrimination, which as the paper will show were not a part of the original oral discourse.

As mentioned earlier, for the current study, the primary focus is on some of the relevant Upaniṣads from the Vedic period, and the Bhagavadgītā from the Epic period. These symbolize theoretical and applied learning and act as foundational sources for later philosophical development.

5 Teaching and learning in ancient India

Teaching and learning in ancient India is presented from the following perspectives; namely teacher-student, four stages of human life, the ideas of non-duality, the world as one family, four fundamentals of an ideal life, distinction between body and soul, idea of karma, and the significance of peace.

5.1 Teacher-student

Upaniṣad appear as conversations, mostly between a teacher and a student, on deep and complex topics, much beyond contemporary textbook. Etymologically speaking, the word ‘Upaniṣad’ is made up of three Sanskrit syllables—upa, which means to move closer; ni, which means ‘at a lower level’; and shad, which means ‘to sit’. So ‘Upaniṣad’ literally translates as ‘sitting close to someone, at a lower level’. This brings to light two important aspects; the first being that a typical teacher-student relationship in India, is hierarchical. A teacher is seen as a provider of ‘ultimate’ knowledge (jñāna), much beyond the written texts, details of which shall be discussed later in the paper. In the Upaniṣads, a teacher is referred to as Bhagavaḥ, meaning the wise and the respected one. A student is referred to as Saumya, meaning faithful. This conceptual nomenclature reveals that the teacher-student relationship is based on trust and authority. Taittiriya Upaniṣad begins and ends with a verse (prayer) (Taittriya Upaniṣad, 3.10.6) devoted to the continued sustenance, and well-being of this relationship, in addition to peaceful coexistence of their thoughts. The teacher is also referred to as a ‘guru’ which etymologically speaking, is made up of two words, ‘gu’ and ‘ru’. ‘Gu’ means darkness (a metaphor for ignorance) and ‘ru’ means dispeller. Therefore, ‘guru’ is seen as the dispeller of ignorance (Advayataraka Upaniṣad, 16–18).

The second aspect is that as a mentor, the teacher is expected to shoulder the holistic growth and welfare of their student, beyond the boundaries of temporality and space. The Upaniṣads show him uncovering the most fundamental experiences of life like suffering, etc., making such like experiences appear as ‘normal’, thereby hel** the student to accept and endure it. Consequently, one of the earliest focuses in ancient education was on the emotional and mental well-being of the student. Such fundamental learnings were skilfully labelled as secrets and made to appear as challenges, stirring enthusiasm and excitement in young flexible minds. Storytelling was used as the most popular pedagogical tool to keep the students involved and participative.

Teaching and learning were outcome based focusing on nurturing respect for resources, despite there being abundance of resources during that time. Some of the lessons for instance taught never to waste food (Taittriya Upaniṣad, Krishna Yajurveda, 3.8–99), have compassion and warmth for those seeking shelter or care (Taittriya Upaniṣad, Krishna Yajurveda, 3.10.1), etc.

The wisdom of the teachers in ancient India reflects their far-sightedness, for they anticipated population growth, increasing diversity, competition for renewable and non-renewable resources [44, 45], etc., in a growing civilization and to ensure abundance and sustenance, they weaved the idea of ‘sacredness’ around everything which needed to be preserved. The French sociologist Emile Durkheim [46], in his work, The Elementary Forms of religious life speaks about sacred not as an inherent trait, but as a quality acquired by being “set apart and forbidden” [47], p. 129). He adds that things deemed as sacred were consumed only on specific occasions and with conscious awareness that it belongs to the collective. This is exactly how the resources, especially the natural resources were viewed by teachers in ancient India. Hymns were written and practices encultured to give them a status of “sacred”. For instance, pṛthvī (Sanskrit term for Earth) Sūkta (hymn) sees earth as a space for all beings and as a provider of resources for each. She is addressed either as a mother or a goddess and worn on the forehead as tilak (dot), as a sign of reverence (Bhaktivedanta [48]. The deeper objective behind such discourse, was not theology but the scientism involving a narrative of respect for resources which were community´s asset.

A unique thing about Upaniṣad is the idea that learning is not viewed as a theoretical embodiment of pre-established historical narratives but as applied knowledge, which is to be self-curated by the student. Taittiriya Upaniṣad views self-learning as a joyful pursuit. Questions asked by the students have evoked further questions from the teachers, thus advancing, and celebrating, constant engagement, treating critical thinking as the prime pedagogical tools, and encouraging multiple perspectives. Teaching and self-learning, in the ancient texts appear as continuous processes.

The idea of institutional teaching and learning, similar to the concept of school today, was very different from the contemporary understanding. There was no defined boundary of concrete. ‘School’ then was not bound by the clock for learning and teaching was a 24/7 activity. The defined skill training and the internalization of undefined multiple skills of everyday living were pursued in the serenity of deep forests, away from all distractions. Days were charted in sync with nature and powerful forces of nature like the Sun. The foundational textbook used to impart knowledge were the Vedas, which mainly comprise of hymns praising the elements that sustain us – the Sun, the rain, the fire, the wind, and the water. Through such narratives, Vedas not only signify the power of nature but also encourage the cultivation of a lasting and sustainable relationship with the larger universe based on trust and mutuality. This is apparent from the fact that distinct salutations were offered to the Sun, with chants making references to it as a friend of all, a provider of cosmic wisdom, an eliminator of darkness (ignorance), and a giver of holistic (mental, emotional, intellectual, and spiritual) nourishment and well-being [49].

5.2 The four stages of life

As mentioned above, the learning spaces in the deep forests were training grounds for skills (theoretical, vocational, and experiential). Every student, by the virtue of his enrolment, was accepted as a member of the teacher’s (guru´s) clan (kul). There were detailed normatively structured principles, both ascriptive and achieved, which qualified a student for learning under a chosen teacher or for an admission into a gurukul (guru´s clan). Ascriptive criteria focused on the community and the family from which he descended, for it was believed that legacy (good or bad) is hereditary. Once accepted, the student stayed with the teacher, 24/7 for almost 15 years, learning skills both tangible and intangible like living in harmony with others, adopting austerities despite their material backgrounds, following the path of righteousness (dharma), evolving social values like compassion, etc. Consequently, such a learning plays a positive role in curating a sustainable society.

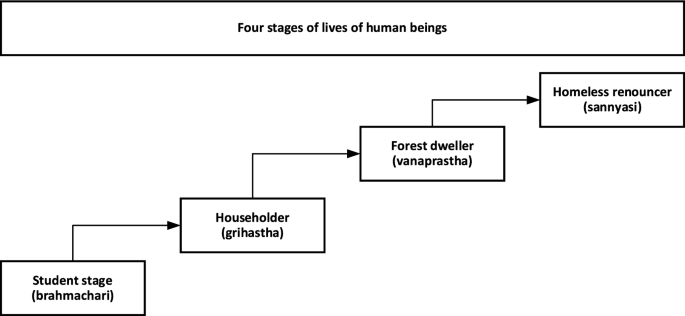

Life of every individual was broadly compartmentalized or divided into four stages, each of which were normatively defined with specific objectives and outcomes, see Fig. 3. “The education of the indi-vidual spirit is arranged through the scheme of asramas or stages of life and varnas or classes of men. It takes into account the different sides of human nature “ [50], p. 7).

The first was the student stage (brahmachari), the stage of learning from the wise, and was marked by “self-control in thought and action” [26], p. 19). With the age of enrolment roughly being 10, the primary focus was on physical and mental growth and development.

Once the teacher felt that his student was ripe (responsible enough) to go back into the mainstream society and enter into a social relationship through marriage (and thereafter procreation), he proactively participated in his transition from the student stage that of the householder (grihastha). It is important for the reader to note that marriage in India, conventionally, is arranged and is a bond between communities, which is seen as lasting beyond the current life. This idea of the cyclical nature of life is discussed later.

The transition to the third stage, that of a forest dweller (vanaprastha), is temporally defined by the birth of grandchildren. It calls for a slow but conscious and steady withdrawal from material things (things appealing to our external senses, including relationships. Undertaking pilgrimages were used as popular tools to distance, distract, channelize, and transform human emotions and attachments into Bhakti Yog (one of the several forms of Yog mentioned later in the paper. Like the first stage, in the third stage too, the members resort to austerities both physical and mental but unlike the first, continue to live within the larger society, participating though not actively, in annual festivities. They were actively involved in guiding and nurturing the two adjacent generations [51].

Once the skill of detachment from the material world was acquired, the transition towards the fourth and the final stage, of the homeless renouncer (sannyasi) began. Radhakrishnan, in a lighter vein, refers to the homeless renouncer as, …the superman of the Bhagavadgita, awakened of Buddhism, the true Brahman who glories in his poverty, rejoices in suffering, and is finely balanced in mind, with peace and joy at heart… [50], pp. 19–20). The sole objective of his remaining life was to build a firm connection with the universal truth, which has been discussed in detail in the next subsection as the belief that the cosmic being lives in everything.

This kind of universally fixed pattern of life, with pre-defined objectives and defined outcomes, may appear coercive to the west but acted as social norms in India and played a significant role in institutionalizing solidarity and interdependence. Despite the vastness of the geography, these norms made existence very disciplined, focused and a lifelong learning pursuit. It also allowed the mind to move beyond fixations and get acquainted with a variety of purposes. Emotionally, the narrative of absolute truth and a patterned living within the community allowed ideas such as compassion and empathy to bloom. All these undoubtedly contribute to making lifestyle and its development sustainable [52].

5.3 Non-duality and the idea of one world one family

The twin philosophies of universe as a creation of the Supreme consciousness, and the omnipresence of this consciousness in all beings, are the prime essentials of the Upaniṣad. These ideas are closely associated with promotion of peace, non-violence, global citizenship, and appreciation of cultural diversity. The Rig Vedic hymn called the Pūruṣaḥ-Sūkta (Rig Veda, 10.7.90.1–16) introduces the divine as the Supreme consciousness (pūruṣaḥ), also referred to as the Mahā-Pūruṣaḥ, Adi-Pūruṣaḥ, Virat Pūruṣaḥ, Bhagwan, Parameshwar, etc. across the translations and even in some original verses and speaks about the sacred sacrifices (offerings) made by this divine cosmic being. The hymn states that these sacrifices are the highest of all the sacrifices, for the pūruṣaḥ ‘consumed’ Himself in the fire of creation, to create the entire universe [53]. It is important to note that there is no specific mention of the gender or form of the divine cosmic creator in the Upaniṣads, however, the translations have used masculine pronouns for the Supreme Consciousness (the creator).

This ‘creation narrative’ from the Rig Veda, appears in several other ancient texts too [54]. The underlying idea is that since everything (and every being) has been created by the Supreme cosmic divinity, by sacrificing His own body, therefore every being manifests divinity within themselves. This fosters the idea of inclusivity and oneness and by extension, makes all creations of this universe divine or manifestations of the divine (non-dual spirituality or Advaita Vedānta) thus respectable (human rights).

When moving from the Vedas to the Upaniṣad, the idea of pūruṣaḥ, without losing its essence, gets replaced by the idea of Brahman (exception being the first verse of Isha Upaniṣad, where word īśā is used). The word Brahman is made up of the root word ‘bṛh’ or ‘brahm’ which means ‘to grow’, and the word mana, which refers to ‘mind’ (full of infinite desires) [55]. Thus, Brahman is an infinite being without any defined finite material form (or gender). This discourse furthers the idea of inclusivity in addition to equitable living.

Learning, understanding, and embracing the idea of Brahman (pūruṣaḥ or īśā) as the one who is omnipresent, and the Universe as one of His several manifestations, is treated as the universal truth and the highest form of knowledge (jñāna yog), involving a combination of intelligence, intuition, wisdom, and empathy. Such a knowledge is regarded as the foundation and root of all knowledge. Teachers in the ancient India, played a significant role in nurturing the self-realization of this universal truth. Since such knowledge is beyond the manifestation of material reality and mundane logic, many western scholars have incorrectly labelled it as mysticism.

Through consistent socialization and internalization of the idea of seeing divinity in ourselves and in every other being, a humanitarian discourse of one world and global citizenship, much beyond external and tangible differences of culture, gender, nation states, etc. is built. The end goal is to respect one’s own body and mind as sacred spaces, nurturing it with love, and eliminating its abuse of any kind. It also calls for respect and kindness toward everything around us. Internalizing such a discourse, built powerful narratives against self-inflicted abuses like drugs, or violence, toxic emotions like anger, bitterness, jealousy, grief, and expectation, filling collective living with joy and affection (Īśa Upaniṣad, 1.6–7).

Īśa Upaniṣad, while talking about the omnipresence of īsa in its opening verse [56], insists on being consciously reminiscent of the need to set aside external appearances and live in unison for all are manifestations of the same divine essence. It reiterates this again later by stating that ‘the’ only way to understand the Supreme divinity is to experience it by perceiving Him in the others (all His creations) [57].

The verse further reads that since everything (and everyone) ‘belong’ to the Supreme, we must not treat anything (including relations) as ‘our’ exclusive possessions. Instead of building false attachments to things or beings, it is argued, we must show gratitude to the divine for all the things (including relations) that He has showered on us as gifts. This idea instils gratitude, appreciation, respect, and humility, all which are values befitting of collective co-existence. It also plays a significant role in facilitating transition from life stage II to III and from III to IV for they involve the idea of detachment at various levels.

Mahā Upaniṣad (one of the minor Upaniṣads) merges the diverse narratives of oneness into the idea of treating the entire world as one family (Mahā Upaniṣad, 6.71–73). In its recent G20 presidency, from December 1st 2022 1st to 30th November 30th 2023, India had set this idea of, vasudhaiva kuṭumbakam (One Earth, One Family, One Future), as the theme [58]. Subsequent verses (Mahā Upaniṣad, 6.74–75), on lines similar to the above-mentioned verse from the Īśa Upaniṣad, argue for detachment and altruism as prerequisites to enable universal experience of the benevolence of the Supreme (Brahman).

Consequently, education encompassed not just intellectual growth but also mental and emotional growth, making Indian civilization, one of the most ancient living civilizations, sustaining itself through the intensive ideas of extensive education.

5.4 The skill to remain focused

Learning was seen as a joyous and passionate pursuit putting every functionality of the human embodiment to appropriate use. The prime objective was focused learning devoid of any distractions, as mentioned earlier. Desires were viewed as the causative of distractions, pushed endlessly by our external sense perceptions which constantly yearn for pleasure, possession, and attachments. Kaṭha Upaniṣad uses a chariot as a metaphor to explain this (Katha Upaniṣad, 1.3.3–5). The chariot is perceived as symbolizing the human body, Intellect or knowledge (Buddhi) as the driver, and Mind (Manah) represent the reins, which control (or get controlled by) the five horses denoting the five external senses. The path which the horses wish to cross represents our selfish desires. An intellect that is immature (has consistent desires), has been referred to as lower (aparā consciousness) and gets enslaved by the mind. Such an immature intellect is unable to discriminate between the absolute truth (the idea of oneness evolving from the union of cosmic being and self) and the universe which is illusionary (maya). It gets invested and wasted in emotional and physical attachments to tangible things and material relationships. Such an indiscriminative mind is restless and anxious because of the constant urge to satiate ever-springing desires arising from the external senses.

It is further argued (Kaṭha Upaniṣad, 1.3.6) that a focused pursuit, paves way for a mature mind which has the capacity to discriminate between the absolute truth and the illusionary universe. Such a cautious and mature pursuit allows us to exercise a certain level of detachment or distance from deep emotional involvements and relationships. It allows us to understand them as transitory, far away from reality. Such a discriminatory understanding, once achieved, guides us to the path of “perfection”. According to the Bhagavadgītā, perfection enables us to dutifully rise above the material ideas of victories and failures and takes us to a level beyond. Such an elevated condition of living empowers us and equips us to endure all life events, with a balanced grace (Bhagavadgītā, 2.48).

5.5 Yog and its forms

Perfection requires a harmonious and balanced interplay between four fundamentals, our external actions (karma), intellect (buddhi), emotions (bhaav), and internal energies (kriya). This can be accomplished through several forms of Yog, involving a disciplined and consistent training of the above-mentioned fundamentals. Yog enables a skilful withdrawal from the distractions of the illusionary world and bridges a connection with the calm Pure Consciousness within. The Bhagavadgītā, illustrates this by giving example of a tortoise, stating that such a pursuit leads to de-cluttering of thoughts and a clear and focused vision. It enables and empowers us to withstand difficulties, which must be accepted as an essentiality of human life (Bhagavadgītā, 2.58). Such an approach makes life emotionally and mentally sustainable.

Depending on the practitioner’s (yogi) choice, Yog can take several forms. The idea of training intellect to detach from the outcomes of our actions (karma) is introduced as Buddhi Yog (Bhagavadgītā 2:47). It is argued that relationships involve commitments, which must be fulfilled as prescribed duties. Consequently, India has long lasting social institutions like family and kinship which act as primary supporters and providers of child and elderly care, and community bonding. However, in the same verse, it is said that we must not have any expectations in return as fruits or recognition. This keeps us away from attachments which could create emotions like jealousy, regret, suffering, pain, etc. The Bhagavadgītā in chapter 3, on Karm Yogi, states that all humans have come to this earth for specific a purpose (duty). Those who shrug or run away from their duties are escapists and those who abandon their duties prematurely are ignorant. None of these two are appreciated. The Wise are those who perform their duties and perceive it as an offering to the divine.

The verse (Bhagavadgītā, 2.58) in its second line (Bhagavadgītā 2:47) states that we must neither perceive ourselves as the cause of the outcome of our activities, nor should we be attached to inaction (non-performance of duty). We all have been born to fulfil specific purposes and we must duly perform our duties. This makes life not just purposive but also meaningful, organized, and systematic, thus sustainable.

Kaṭha Upaniṣad, introduces the idea of adhyātma-yog, to enable the realization of non-dual spirituality through self-contemplation, which as mentioned earlier is considered to be the universal truth and is the highest form of knowledge (jñāna) (Kaṭha Upaniṣad, 1.3.14). To experience this, insist the Upaniṣad, one must contemplate and meditate deeply on the highest chant AUM (also known as Pranava or Udgitha). The importance of AUM and its relationship with the several stages of our consciousness have been dwelled upon in the Māṇḍūkya (1.1–12).

Since a life devoid of distractions is not an easy path, Upaniṣad do accepts that practicing adhyātma-yog with devout focus is not simple. It is sprinkled with pain and difficulties, thus demanding great courage (Kaṭha Upaniṣad, 1.3.14). It is best lived when we live according to the four fundamentals of ‘ideal’ life (puruṣārthas) in accordance with the ancient Indian philosophy, by pursuing dharma, artha, kāma, and mokṣa.

5.6 Four fundamentals of ‘ideal’ life (puruṣārthas)

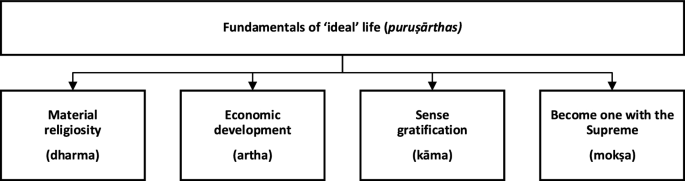

Value-based education has been fostered in India since times immemorial. Out of the above mentioned four fundamentals of an ‘ideal’ life, dharma, artha, kāma, and mokṣa, see Fig. 4, the concept of mokṣa was introduced later in the Upaniṣad, while the preceding Saṃhitās, Brāhmaṇam, and Āraṇyaka do mention the first three. Some argue [59] that the first known sources mentioning the four together are the epics Ramayana and Mahābhārata and the Dharmaśāstras (based on ancient Dharmasūtras, which themselves emerged from the Brahmana layer of the Vedas).

Dharma is righteousness and demands moral unrighteousness, performance of and fulfilment of our duties and responsibilities. The usage of the term artha, with respect to life is to lead it meaningfully to be meaningful, life must have a goal and purpose, which amidst other things, must also include the welfare of the larger community, in addition to acquiring material wealth through morally upright means. Kāma refers to pleasure and to lead a life with pleasure meant that we must treat it as a celebration (within the boundaries of dharma) and not as a burden. Mokṣa or liberation was considered the highest goal of human life. It valorized freedom as detachment from attachments (bondages). While translating and writing a simultaneous commentary [60]. Prabhupada [60] refers to dharma as “material religiosity”, artha as economic development, kāma as “sense gratification”, and mokṣa as “an attempt to become one with the Supreme”.

5.7 Distinction between the body and soul and the idea of karma

Ancient Indian Philosophy skilfully distanced an individual from the fear and pain of separation and death by separating the body from the soul. It is argued that once discriminative knowledge is acquired, the body and soul can be comprehended as distinct with the former being transitory while the latter, eternal, and permanent. Death signifies the end of only the body while the soul is unborn and primeval and moves on to another body (Bhagavadgītā 2.22).

According to Īśa Upaniṣad, the soul is the master of the body and is not defined by or restricted to the experiences of the body. It is indestructible and insoluble, like the divine cosmic being. When death comes, the soul breaks free. This thought has been very explicitly illustrated through a narrative on the cyclical flow of birth and rebirth (saṃsāra), and life beyond death, in the Kaṭha Upaniṣad (1.6) too. Just as a person puts on new garments after discarding the old ones, says the Bhagavadgītā, the living entity or the individual soul acquires a new body after casting away the old body (Bhagavadgītā 2.22). A similar understanding is received from the Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad (4.4.3) [61].

No human on this earth, states the Bhagavadgītā, can be in state of inaction. Depending upon their qualities, all humans are innately karmic (action oriented) (Bhagavadgītā 3:5) for actions or deeds (karmas) are determinants of the next journey of our soul (Īśa Upaniṣad, 17–18). It is only the fire of highest form of knowledge (self-realization of universal truth) that can turn to ashes (or undo) the consequences of our material actions (Bhagavadgītā 4:37).

Broadly speaking there are three kinds of karmas [62]: the accumulated ones (from our previous births called sachita; the ones whose effect we are rea** in the current life (parabdha); and the ones which we perform today, consequences of which shall be on our future (agami). The first and the last can be zeroed by the attainment of the highest form of knowledge. But the second can be exhausted only by experiencing their consequences.

…When we leave this world, we take nothing with us. …But we take something with us. Like an encrustation that has grown upon us, the forces of Karma cling to our subtle body which alone departs when the physical body is shed (Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad, 4.4.6). In some other Upaniṣhad it is said that a calf finds its own mother even in the midst of a thousand cows by moving hither and thither in the herd; as it goes to its own mother though the cows may be thousands in number, likewise our Karma will find us wherever we are [63], p. 445).

This narrative compels humans to exercise restraint and cautionary discretion in everyday conduct. Mindful efforts must be made to weave positive actions which necessarily include charity and other welfare activities. It is argued that even the thought has the power to determine our next birth (Bhagavadgītā 8:6). Sharing or sacrificing the ‘gifts’ bestowed on self is the best form of service or offering to the Supreme. It is a reliable pathway to immortality.

5.8 Significance of peace

Every Upaniṣad begins with a special prayer (mantra) for peace (śāntih mantra) which was recited before the Upaniṣad was explained. Each of these prayers end with repetition of the sacred syllable AUM, thrice. This is because it invokes peace at three levels, peace within, peace within the community vis a vis other being, and peace vis a vis the natural environment and larger universe.

Peace prayer of the Principal Upaniṣads (Aitareya) associated with the Rig Veda ask for elimination of all kinds of distractions, harmonious synchronization between mind and words, and internalization of that which is taught [64]. It ends with a request to protect the teacher and also the self. Peace prayer of the Principal Upaniṣads (Chandogya and Kena) associated with the Sama Veda ask for nourishment of all senses and ability to internalize the wisdom rooted in the Upaniṣads [65]. Peace prayers of the Principal Upaniṣads associated with Yajur Veda, subdivided into Shukla Yajur Veda (Isha, Brihadaranyaka) and Krishna Yajur Veda (Katha, Taittiriya), asks for a feeling of completeness which is blissfully desireless [66]. Following this, there is another prayer which asks for protection for all [67]. It desires energy and strength for all and resonates with the idea of universal mankind and oneness when it asks for elimination of differences and establishment of harmony. Peace prayer of the Principal Upaniṣads (Mandukya, Mundaka, Prashna) associated with the Atharva Veda asks for distance from negativities, hearing the pleasant, seeing the blessed, and a life which can be dedicated to the service of the divine creator and all his creations [68].

All the prayers curate a desire for harmony, peace, collective well-being and joyful co-existence in the minds of the learners. The sound and words of these mantras are believed to calm the mind and facilitate learning [43]. The significance of Vedic chanting has been globally recognized and registered [69].

6 Discussion and implications

Analysing and placing India’s ancient rich ancient philosophy and its focus on holistic education in the context of target 4.7 of the Sustainable Development Goals, and relevant international commitments and discussions reveals that because of its intensive depth and extensive richness it indeed can act as a prototype for deepening the understanding of what holistic education for sustainable development entails. Tying the SDGs to spirituality has been previously be done, [13] but not from the educational or the Indian philosophical point of view. Table 1 synthesizes the main ideas and semantics settings relevant to sustainability, to provide an ideal type of holistic education for sustainability. Key ideas have been categorized based on social and cultural, ecological, economic, and educational settings, in addition to highlight cross cutting themes and/or spiritual settings. The grey-shaded boxes in the table mean that particular settings are not evident in the respective models and frameworks that serve collectively as a foundation for a model of holistic education.

The synthesizes from Table 1 reveals that the planetary boundary framework only addresses the environmental setting, the doughnut economy model adds elements relevant to the social/cultural setting, economic setting, as well as the educational setting, although only mentioning quality education without further explanation. Similar aspects can be found in the SDGs wedding cake model, although it adds a cross cutting theme emphasising that partnerships (Goal 17) are important for reaching the SDGs. Pope Francis Laudato Si' Goals provide understanding of important elements for addressing sustainability issues as can be drawn collectively from previous models and frameworks, although it adds to the discussion on education by emphasising particularly ecological education (Goal 5, and that it should take place at schools, in families, in the media, in catechesis and elsewhere. Furthermore, ecological spirituality (Goal 6) is also stated as a relevant aspect when addressing sustainability issues. The holistic education key principles offer insights to all categories except for the economic setting, deepening understanding in the educational setting by bringing up how students should be honoured as individuals (Principle 2), addressing the central role of experience (Principle 3), emphasising the wholeness of the educational process (Principle 4), as well drawing the attention to the role of educators (Principle 5), thereby representing a “profound respect for the deeper, largely unrealized power of human nature [34], p. 2).

Target 4.7 of SDG4, quality education, is then narrower in the sense than the collective ideas drawn from previously discussed models and frameworks. It does not address the ecological or the economic settings, although the main aims are education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles as well as relevant knowledge and skills to promote sustainable development. It should, however, be noted that education plays a key role in many of the SDGs, including the eliminating poverty (Goal 1), affordable and clean energy (Goal 7), decent work and economic growth (Goal 8), reduction of inequalities (Goal 10), responsible consumption and production (Goal 12), climate action (Goal 13), and partnership for the goals (Goal 17) [6].

As brought up in the paper, the word 'Education' itself includes some of the essential elements such as Equity, Development, Universality, Compassionate virtues, Acceptance, Training, Inclusivity, Opportunities for All, and Nurturing, all of which play a significant role in strengthening the foundational integrity of ‘sustainability’. This requires a holistic view of education and what it entails so that the ideal type of holistic education for sustainability can be proposed. Therefore, analysis of the rich ancient Indian philosophy can help provide more holistic views on what this entails beyond SDG target 4.7 and the ideas from the frameworks and models presented in the paper and in Table 1.

From the Indian philosophy on holistic education the Socio-cultural setting, see Table 1, emphasises of non-duality and perceiving the Universe as the creation of the Supreme by sacrificing and investing His own physical, emotional, and mental Self plays a very strong role in enforcing respect not just for fellow humans but also for other living beings. It further evokes submission to the larger environment and the natural resources by treating them as embodiments of the Supreme and humans as mere caretakers. This consciously woven hierarchy keeps a check on the ecological balance. The idea of forest spirits, mountain elves, water goddesses, etc. which appear as mysticism to the outsiders, in fact, have had deep symbolic significance for sustainability. Ancient philosophy treats them as personified, living, totemic emblems serving as providers and patrons of human existence. This is consistently perpetuated and manifested by calendrical rituals and pilgrimages which function as tributes to providers of ecological sustenance. Such a philosophical tone voices ideas of compassion, non-violence, peaceful coexistence, and community resilience. The understanding of oneness and global citizenship evolves a step ahead when we read about vasudhaiva kuṭumbakam (One Earth, One Family (One Future (authors´emphasis)) in the Mahā Upaniṣad (6.71–73). Being a collective society, each generation has the responsibility to provide for the sustenance of the next. Admission of a child into the student stage was seen as a movement from his ascriptive kin group to the kin group of his teacher, pledging loyalty forever. Teacher in return served as his mentor forever. This exhibits the depth and the strength of the Teacher-Student bond.

The philosophy of perceiving roles and responsibilities, both ascriptive and achieved, as the pathways to rewards in the future and/or as punishments for past deeds builds endurance and sustains focused perusal. Social norms thus acted as the means to social control, stability, and order. Skilful channelling of physical, emotional, and mental energies through several forms of Yog serves as an instrumental tool to empower and to build harmonious co-existence within the self, with others, and with the larger universe. Thus, the philosophy adeptly includes mental and emotional well-being.

With respect to the ecological settings, learning and teaching during the ancient period were organized in deep forests where all students lived as members of the family of the teacher. Thus, curating emotional bonding with the ecology. Conscious steps such as modest uniforms, lessons in food-gathering and cooking, serving, etc. were evolved to eliminate differences and structure a disciplined routine clocked in tune with nature. This subtly led to the internalization of respect for resources and trust in nature. Chants signifying the incessant glory of and gratitude towards ecology hold paramount significance in ancient Indian philosophy. As mentioned above, restraint and respect were expected of humans as Mother Nature in her several manifestations was perceived as a provider and sustainer of life. The Universe and its plenitude, in ancient philosophy, is seen as a generous gift by the Supreme and to be shared among all. This called for humility and gratitude, through preservation and conservation.

Ancient philosophy treats desire as the root cause of suffering and the material world as an illusionary creation, draws focus to the economic setting. Student life involved the adoption of uniform clothing, austerities, and minimalistic living. An abundance of resources in later life was seen as symbolic of being the chosen one to share the entitlements with others. The wider the spectrum of welfare, the higher the probability of rewards in this birth and in future rebirths. Food, housing, shelter, health, children, etc. were all seen as gifts or grace, and their wastage or asocial abuse was seen as an evil act.

With reference to the educational setting, ancient philosophy accorded a sacred status to education and all the stakeholders (teacher, student, parents, and the community) were mandated to harmoniously fulfil their respective roles with due diligence and absolute righteousness. The teacher was perceived as a mentor. The syllabus was vast, intricately intertwined with everyday life skills. The learnings were anchored in experience and self-discovered through discussions and questions. The knowledge received was referred to as jñāna (wisdom). The focus was on holistic education using interactive pedagogies like participative learning, experiential learning, critical thinking, etc. Demonstrative application of skill-based learning was consciously evolved by creating real-life conditions demanding the application of knowledge. Ecology was viewed as a canvas within which this learning was curated.

In relation to the cross-cutting themes and/or the spiritual setting the foundation of ancient Indian philosophy is spirituality but has often been wrongly misconstrued by the orientalists as religion. The philosophy is of sanatam dharma which when translated into English would roughly mean universal codes of morality. These codes were penned as righteous, meaningful, passionate perusals closely intertwined with harmonious co-existence. The Supreme was perceived as a formless, genderless, omnipresent consciousness. Service toward mankind was the only form in which the Supreme could be served. Social was most significant for it was viewed as an embodiment of collective conscience. Understanding the principle of non-duality and the material world as a mere illusion was perceived as the highest form of knowledge. The ancient teachings appear as random revelations and were written down much later. Spirituality has been used as an instrument for social control, with emphasis on the ideas of samsara, and karma. These philosophical concepts acted as anxiety pacifiers and confidence boosters. Several forms of yog served as roads to spirituality through balanced self-contemplation.

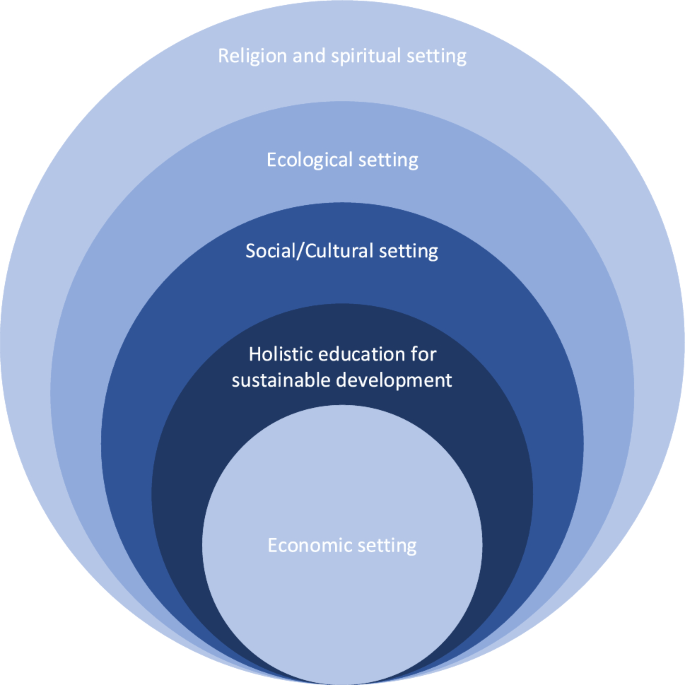

Drawing from the above discussion we propose a diagram showing a prototype on what holistic education for sustainable development entails, see Fig. 5. What it suggests is that spirituality and religion envelope the other settings in the diagram guiding evoking submission to a higher power, the supreme. Within this setting is the ecological setting where natural environment and resources are treated as embodiments of the supreme and humans as mere caretakers of the environment. The social and cultural setting enforces respect for fellow humans as well as other living beings, and emphasizing the importance of individuals and their physical, emotional, and mental well-being. To enlighten learners about this philosophy is education that is holistic and relevant to real-life conditions. Finally, is the economic setting including the material aspects of life. This setting gets the least emphasis in the diagram, as other settings are considered more important in the case of holistic education. This suggest that some elements, and depth in the discussion, are missing from the previously mentioned models and frameworks and Target 4.7 of the SDG4. ‘Ideal type’ [24] has been used not as an absolute explanatory tool but to evolve model/s for sustainable education, and for education that can advance sustainability.

Drawing from Weber’s ideal type constructed as an “emergency safe haven(s) until one has learned to find one´s bearings while navigating the immense sea of empirical facts” [31], p. 133), what is in particular missing in target 4.7 and the models and frameworks presented is the focus on higher power and the mental well-being of individuals from Indian philosophy suggesting than one should live in harmony with universe to sustain existence of all living beings and act as a reminder for internalizing peaceful coexistence and respect for human and non-human resources.

7 Conclusions

The transference of knowledge is at risk given change in oral communication channels, although there is more willingness to listen to Indigenous Peoples by national governments and actors within the international political system. The paper demonstrates how ancient philosophy can be used to deepen the understanding in the context of target 4.7 of SDG4, and other relevant models and frameworks, our understanding of what holistic education entails. This is furthermore presented in Table 1 and Fig. 5.

Authors acknowledge that language and symbols carry deep cultural significance and meaning and have been conscious in ensuring their best to do justice to it and are aware of the tendency of the “book view” (Indological Approach) to homogenize but this is in tune with the objective intending to draw an ideal–typical proto-type of holistic education as presented in Fig. 5.

This paper only deals with one aspect of sustainable development and the SDGs, that is education. However, the paper conceptualization can serve as a comparative tool for sha** the empirical global reality. It gives the possibility to look at other elements of sustainable development or the SDGs in a similar way, i.e., by learning from ancient philosophy and what lessons it has to offer to modern societies on how to address local or global challenges.

Data availability

No primary data was collected, see the reference list and citations for sources used.

References

Rockstrom J, Steffen W, Noone K, Persson A, Chapin FS III, Lambin E, Lenton TM, Scheffer M, Folke C, Schellnhuber H, Nykvist B, De Wit CA, Hughes T, van der Leeuw S, Rodhe H, Sorlin S, Snyder PK, Costanza R, Svedin U, Foley J. Planetary boundaries:exploring the safe operating space for humanity. Ecol Soc. 2009;14(2):32.

Stockholm Resilience Centre. (n.d.-a). Planetary boundaries. Retrieved October 3 from https://www.stockholmresilience.org/research/planetary-boundaries.html

Raworth K. A Safe and Just Space for Humanity Oxfam GB. 2012. https://www-cdn.oxfam.org/s3fs-public/file_attachments/dp-a-safe-and-just-space-for-humanity-130212-en_5.pdf

United Nations. (n.d.-b). The Sustainable Development Agenda. Retrieved October 8 from https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/development-agenda/

UNFCCC. Adoption of the Paris agreement. (FCCC/CP/2015/L.9/Rev.1). Paris: United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; 2015.

United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023. Special. Towards a Rescue Plan for People and Planet: United Nations Publications; 2023.

United Nations. SDG Indicators. 2023. Retrieved October 3 from https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/indicators/indicators-list/

Cerf ME. The social-education-economy-health nexus, development and sustainability: perspectives from low- and middle-income and African countries. Discover Sustainability. 2023;4(1):37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-023-00153-7.

United Nations Development Programme). The SDGs in action. 2023. Retrieved October 3 from https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals

Stockholm Resilience Centre. (n.d.-b). Sustainable Development Goals: The SDGs wedding cake. Retrieved October 3 from https://www.stockholmresilience.org/research/research-news/2016-06-14-the-sdgs-wedding-cake.html

Pope Francis. Encyclical Letter Laudato Si’: On Care for Our Common Home. 2015. Retrieved October 3 from https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/encyclicals/documents/papa-francesco_20150524_enciclica-laudato-si.html

Villas Boas A, Esperandio MR, Caldeira S, Incerti F. From selfcare to taking care of our common home: spirituality as an integral and transformative healthy lifestyle. Religions. 2023;14:9.

Batra. Spiritual Triple Bottom Line Framework- A Phenomenological Approach. IIMB Management Review. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iimb.2023.04.006

Honward S. Learning to balance indigenous and exogenous knowledge systems for environmental decision-making in the Kumaon Himalayas. In R. J. Tierney, F. Rizvi, & K. Ercikan (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of Education (Fourth Edition) (pp. 349–357). Elsevier. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-818630-5.13076-3

Vammen Larsen S, Bors E, Johannsdottir L, Gladun E, Gritsenko D, Nysten-Haarala S, Tulaeva S, Sformo T. A Conceptual Framework of Arctic Economies for Policy‐making, Research, and Practice. Global Policy, September 2019, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12720

Foucault M. Archaeology of Knowledge and the Discourse on Language. Tavistock Publications Limited; 1972.

Dirks NB. Castes of Mind: Colonialism and the Making of Modern India. Princeton University Press; 2001.

Baudrillard J. Simulacra and Simulation (S. F. Glaser, Trans.). The University of Michigan Press; 1994.

King R. The Varieties of Hindu Philosophy. In Indian Philosophy: An Introduction to Hindu and Buddhist Thought (pp. 42–74). Edinburgh University Press; 1999. https://www.jstor.org/stable/https://doi.org/10.3366/j.ctvxcrtt5.8

Tigunait PR. Seven Systems of Indian Philosophy. Tradeselect Limited. 2018. https://books.google.is/books?id=dbMttAEACAAJ

Kempny M. Malinowski's Theory of Needs and its Relevance for Emerging of the Sociological Functionalism. Polish Sociol Bull. 1992; 97, 45–56. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44816942

Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (2 ed.). Sage Publications, Inc.; 2007.

Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

Hendricks J, Peters CB. The Ideal Type and Sociological Theory. Acta Sociologica, 1973; 16(1), 31–40. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4193914

Ram Dass Love Serve Remember Foundation. (n.d.). Finding harmony in today's world: Ram Dass on the mystical wisdom of the Bhagavad Gita. Retrieved October 15 from https://www.ramdass.org/gitacourse/

Easwaran E. The Upanishads (2 ed.). Nilgiri Press; 2007.

Paramananda S. The Upanishads: From the Original Sanskrit Text. Axiom Australia; 2004.

Radhakrishnan S. The Principal Upanishads George Allen & Unwin; 1953.

Swami S. Srimad Bhagavad Gita With Text, Word for Word Translation English Rendering, Comments and Index - Hardcover. Advaita Ashram; 1909.

Yogananda P. The Bhagavad Gita: God talks with Arjuna: royal science of God-realization: the immortal dialogue between soul and spirit: a new translation and commentary. Self-realization Fellowship; 2001.

Weber, M. Max Weber: Collected Methodological Writings (H. H. Bruun & S. Whimster, Eds. 1st ed.). Routledge; 2012. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203804698

United Nations. (n.d.-a). Goals: 4 Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all. Retrieved June 28 from https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal4

Mahmoudi S, Jafari E, Nasrabadi H, Liaghatdar M. Holistic education: an approach for 21 century. Int Educ Stud. 2012;5(3):178–86. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v5n3p178.

Miller, J. P. (2018). Holistic Education. In J. P. Miller, K. Nigh, M. J. Binder, B. Novak, & S. Crowell (Eds.), International Handbook of Holistic Education (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315112398

Dahlberg K, Drew N. Reflective Lifeworld Research. Studentlitteratur; 2001.

Matsui K. Problems of Defining and Validating Traditional Knowledge: A Historical Approach. Int Indig Policy J. 2015;6:2. https://doi.org/10.18584/iipj.2015.6.2.2.

Reyes-García V. The relevance of traditional knowledge systems for ethnopharmacological research: theoretical and methodological contributions. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2010;6(1):32. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-6-32.

State Government of Victoria. Traditional knowledge. 2021. Retrieved June 29 from https://www.aboriginalheritagecouncil.vic.gov.au/taking-care-culture-discussion-paper/traditional-knowledge

Grenier L. Working with indigenous knowledge: A guide for researchers. International Development Research Centre; 1998.

Mistry J, Jafferally D, Ingwall-King L, Mendonca S. Indigenous Knowledge. In A. Kobayashi (Ed.), International Encyclopedia of Human Geography (Second Edition) (pp. 211–215). Elsevier; 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-102295-5.10830-3

Radhakrishnan S, Moore CA, (Eds.). A Source Book in Indian Philosophy; 1957.

Swami SP, Yeats WB. The Ten Principal Upanishads. Rupa & Company; 2005. 9788129128768.

Pai R. The Vedas and Upanishads for Children. Hachette India; 2019.

Inden R. Orientalist Constructions of India. Modern Asian Studies, 1986; 20(3), 401–446. http://www.jstor.org/stable/312531

Said EW. Orientalism. Pantheon Books; 1978.

Durkheim É. The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. Free Press; 1995.

Durkheim É. Emile Durkheim on Morality and Society. In R. N. Bellah (Ed.), Heritage of Sociology Series. University of Chicago Press; 1973.

Bhaktivedanta Ashram (2012). Prithvi, the Earth Mother. Retrieved October 3 from https://www.indiadivine.org/prithvi-the-earth-mother/

The Art of Living. (n.d.). Yoga: Sun Salutation mantras and their meaning. Retrieved October 2 from https://www.artofliving.org/yoga/health-and-wellness/sun-salutation-mantras

Radhakrishnan S. The Hindu Dharma. Int J Ethics, 1922; 33(1), 1–22. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2377174

Shah AM. The Family in India: Critical Essays. Orient Longman Limited; 1998.

Grant L, Reid C, Buesseler H, Addiss D. A compassion narrative for the sustainable development goals: conscious and connected action. Lancet. 2022;400(10345):7–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01061-3.

Sundar SV. The Purusha Sukta - The Vedic Hymn on the Supreme Being. 1995. Retrieved August 31 from https://ramanuja.org/purusha/sukta-intro.html

Four Legs of Dharma. (n.d.). Rg Veda 10.90 - Purusha Sukt. Retrieved October 2 from https://sacred-texts.com/hin/rigveda/rv10090.htm

Kalita D. Brahman in the Upanishads. International Journal of Sanskrit Research, 2020;6(5), 74–75. https://www.anantaajournal.com/archives/2020/vol6issue5/PartB/6-5-13-337.pdf

Upanishads.org. (n.d.). Upanishads. Retrieved October 2 from https://upanishads.org.in/upanishads/1/1

Krishnananda S. (n.d.). Lessons on the Upanishads: Chapter 4: The Isavasya Upanishad. Retrieved October 8 from https://www.swami-krishnananda.org/upanishad/upan_04.html

Ministry of External Affairs. G-20 and India’s Presidency. 2022. Retrieved August 31 from https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1882356

Wikipedia. (n.d.). Puruṣārtha. Retrieved October 2 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Puru%E1%B9%A3%C4%81rtha#cite_ref-14

Prabhupada S. Bhagavad-gita As It Is (2nd ed.). Bhaktivedanta Book Trust; 2019.

Mādhavānanda S. The Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad (with the Commentary of Śaṅkarācārya) (2021 ed.). Advaita Ashrama; 1950.

Sivananda S Secrets of Karma. The Divine Life Society. 2020. Retrieved October 2 from https://www.sivanandaonline.org/?cmd=displaysection§ion_id=1180

Krishnananda S. The Brhadaranyaka Upanishad. The Divine Life Society; 1983. https://www.swami-krishnananda.org/brdup/Brihadaranyaka_Upanishad.pdf

Shlokam. Vang Me Manasi Pratisthita. 2023e. Retrieved October 2 from https://shlokam.org/vangmemanasi/

Shlokam. Apyayantu Mamangani. 2023a. Retrieved October 2 from https://shlokam.org/apyayantu/

Shlokam. Purnamadha Purnamidam. 2023c. Retrieved October 2 from https://shlokam.org/purnamadha/

Shlokam. Sahana Vavatu. 2023d. Retrieved October 2 from https://shlokam.org/sahanavavatu/

Shlokam. Bhadram Karne. 2023b. Retrieved October 2 from https://shlokam.org/bhadramkarne/

UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage. (n.d.). Tradition of Vedic chanting. Retrieved October 2 from https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/tradition-of-vedic-chanting-00062

Raworth K. Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist. Random House Business; 2017.

Funding

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: SKB and LJ; Methodology: SKBLJ; Formal analysis and investigation: SKB and LJ; Writing—original draft preparation: SKB and LJ; Writing—review and editing: SKB and LJ; Funding acquisition: [n/a]; Resources: [n/a]; Supervision: [n/a].

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Babbar, S.K., Johannsdottir, L. India’s ancient philosophy on holistic education and its relevance for target 4.7 of the United Nations sustainable development goals. Discov Sustain 5, 51 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-024-00225-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-024-00225-2