Abstract

Background

Physical activity-based interventions to improve children’s wellbeing is a fast-growing research domain. Attention is being directed to unstructured play, dance, and popular forms of mind-body wellness techniques such as yoga and meditation. Immigrant children in resource-rich countries are a growing population. Physical education, recreation, and dance-related interventions are gaining prominence for hel** immigrants adjust to new surroundings.

Objectives

This pre-study aims to compare the impact of unstructured play, dance sessions, and yoga-meditation sessions on US-based South Asian immigrant children’s happiness outcomes.

Method

A three-group comparison proof-of-concept study was undertaken with outcomes compared for the three cohorts at pre- and post-test stages.

Results

Participants in the yoga-meditation sessions reported significantly higher scores on the happiness measures compared to unstructured play and dance sessions participants (Hedges’ s g=0.48 –0.68, p=.002–.034). Immigrant girls, whose primary caregiver parent had higher formal education (postgraduate degree/professional degree), who lived in a standard family arrangement (with both parents and siblings), and whose intervention compliance was higher (>50% attendance and homework completion), gained more. Tobit model-fit statistics and parameters further suggested that it was possible to estimate the extent of post-test changes in outcomes due to yoga-meditation sessions attended and homework completed alone, controlling for significant socio-demographics.

Conclusions

Yoga-meditation sessions could be useful, diversity-accepting, and inclusive tropes for US-dwelling South Asian immigrant children’s psychological wellness and happiness. Further modifications may be needed for boys, immigrant children with less formally educated primary caregiver parents and living in alternative family set-ups (such as with one parent and/or caregiver).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Physical activity-based interventions to improve children’s wellbeing is a fast-growing research domain. Physical activity leads to positive improvements in personal and social development of school-aged children (Marron et al., 2021) as well as health-related outcomes (Abdulla et al., 2021). Researchers have acknowledged that moderate to vigorous physical activity and regular time spent improves physiological markers of good health in children (Kelso et al., 2021). There are gender and regional differences in levels of physical activity and attitudes to physical education among children. Studies have suggested that boys are more positively inclined to physical activity and children from cultures that give importance to physical activity through incentives (including grades) are more physically active (Mauvais-Jarvis et al., 2020; Tcymbal et al., 2020).

Within this research domain, attention is being directed to unstructured play, dance, and popular forms of mind-body wellness techniques such as yoga and meditation. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have affirmed that unstructured play as a form of physical activity has long-lasting benefits for children’s overall wellbeing (physical, social and emotional) and development (Lee et al., 2020; Trimboli et al., 2021), including for children with special needs (Francis et al., 2019). Unstructured play, indoors or outdoors, and the time spent improves physical wellness, cognition, mental wellness and general happiness in children across cultures (Bento & Dias, 2017). Scholars have suggested that outdoor, free and nature-rich play also supports healthy brain development by encouraging exploration and strengthening orientation, decision-making skills and the ability to respond to a changing context (Kahn & Kellert, 2002).

Unstructured play activities of children are impacted by location, environment, societal and cultural attitudes, age, gender, parental support and socio-economic status. Some researchers suggest that rural children are more active in outdoor play compared to their urban counterparts and levels of urbanization and walkability/space to play are crucial factors (Brussoni et al., 2020). Social norms and neighborhood perceptions around play impact children’s play activities (Loebach et al., 2021). In addition, though the evidence is inconclusive and sometime conflicting, younger children, boys, children belonging to privileged socio-economic backgrounds and with supportive parents are more likely to engage in meaningful outdoor play (Delisle Nyström et al., 2019). Researchers have suggested that older children are more likely to engage in sedentary play activities on digital media and devices, young girls are more inclined to play make believe games indoors, and children whose parents do not recognize the importance of free play or are constrictive of children’s independent outdoor movements, play less (Deng et al., 2021). Köngäs et al. (2021) further suggest that peer culture is an important factor determining play activities of children. Country-level environmental factors including education policies explain cross-national variations in children’s physical activity (Weinberg et al., 2019). Anthropometric parameters of children such as body mass, height and body mass index impact physical activity (Latorre-Román et al., 2017). Particularly with respect to parental role, levels of parental control and support (Doggui et al., 2021), gender, parental education and their views on physical education (Ružbarská et al., 2021) and perceptions of actual parenting role related to children’s physical activity or sedentary behaviors (Andermo et al., 2021), impact children’s play activities.

Dance is another form of physical activity that is considered effective for children’s wellbeing (dos Santos et al., 2021). Research on dance education for children has emphasized its effectiveness for physical and mental health and wellness (Grindheim & Grindheim, 2021; McCrary et al., 2021). Studies have compared forms of dance (for instance, interactive vs aerobic or ballet vs hip-hop/salsa or western forms vs indigenous dance forms) (Letton et al., 2020; Payne & Costas, 2021), dancers to non-dancers (Aithal et al., 2021; Schneider & Rohmann, 2021), and dance with other forms of physical activity (Fong Yan et al., 2018), and found dance interventions in general to be effective (with age- and culture-specific variations in forms) in enhancing physical health and mental wellbeing in children. The impact of dance varies based on gender, ethnicity, parental support in case of children, and practice. Girls are more inclined and motivated to participate in dance sessions possibly also due to cultural factors that associate dance as a feminine activity (Gramespacher et al., 2020; Silva et al., 2021). Certain forms of dance such as ballet are more effective for certain privileged ethnic groups and perpetuate racial stereotypes and inequities linked to body, aesthetics, performance, privilege, and race (Culp, 2020; Oliver, 2020). For children, parental support, inclination, and attitudes to dance are important factors linked to their motivation to dance (Buck & Turpeinen, 2016). Like any art form, the effectiveness of dance and mastery of techniques is possible with participant engagement and self-practcie (Ørbæk & Engelsrud, 2021).

There is burgeoning evidence on body-mind techniques of physical education such as yoga and meditation as beneficial for all practitioners and children in particular (Wieland et al., 2021). Yoga is a set of physical, mental, and spiritual practices that have evolved over time and are now practiced in a range of forms throughout the world. Yoga comprises postures, breath control, and is often done in combination with meditation (Feuerstein, 2012). Meditation as a spiritual technique comprises breath regulation, concentration, and centering (Goyal et al., 2014). Researchers have suggested that yoga and meditation interventions improve psychological functioning and help mitigate stress, promote self-regulation, academic engagement, and wellbeing among children (Filipe et al., 2021; Vekety et al., 2021). Two meta-analyses have indicated that mindfulness meditation improves cognition, academic performance and emotional/behavioral regulation among children (Klingbeil et al., 2017; Maynard et al., 2017). Meditation improves children’s performance on cognitive functioning (Felver et al., 2017; Lawler et al., 2019) compared to passive control group (Quan et al., 2019). Meditation also promotes psychological wellbeing among children compared to waitlist groups and emotional literacy program participants (Alampay et al., 2020; Janz et al., 2019). In particular, yoga and meditation training have been shown to also positively impact emotional mental health and wellbeing and improve happiness outcomes in school children (Guendelman et al., 2017) compared to waitlist control groups.

The impact of yoga and meditation interventions is moderated by participant socio-demographics such as gender, education, economic class, marital status, personality characteristics, cultural familiarity, parental variables in case of child practitioners, and self-engagement comprising attendance fidelity and homework completion. Researchers have suggested that yoga-meditation interventions impact women more as the aim is to reduce the tendency to ruminate, which women often tend to do when faced with stress (Upchurch & Johnson, 2019; Wang et al., 2021). Though the evidence is still inconclusive, participants with higher formal education and of privileged socio-economic status gain more from yoga and meditation interventions (Ding & Stamatakis, 2014; Park et al., 2015). Similarly, some studies advocate gains in marital stability and quality through yoga and meditation interventions (Ripley et al., 2014) and yet others suggest that singles, especially widowed participants gain more (Michael et al., 2003). Participants who belong to conscientious and introverted personality types, gain more from yoga-meditation interventions (Patwardhan, 2017; Solomon & Esmaeili, 2021). Cultural familiarity with yoga and meditation techniques is a booster for gains from the same (Mishra et al., 2020). Parental variables positively impacting child practitioners include parental inclination and motivation, attitudes towards the yoga-meditation, and their own levels of religiosity/spirituality (Bird et al., 2021; Duncan et al., 2009; Padgett et al., 2019). Researchers have acknowledged that whereas there is a need to be alert to adverse events (Britton et al., 2021), intervention fidelity and homework compliance are strong predictors of the positive impact of yoga and meditation (Cartwright et al., 2020; Masheder et al., 2020; Schlosser et al., 2019).

Immigrant children in resource rich countries are a growing population. There is growing research on issues of immigrant children from the global South who move with their caregivers to live outside their home countries, including acculturation stress, adjustments concerns, and challenges with education in the foreign land (Dababnah et al., 2021; Haley et al., 2021). Adapting to formal and non-formal education in the foreign land comprises getting used to the school curriculum and physical activities of varied nature (see Rheaume, 2019). This is impacted by gender, race, ethnicity, parental assimilation, and peer group factors. Immigrant boys and immigrant children of certain racial and ethnic groups more aligned to habits of the natives adapt better (Qian et al., 2018). Higher formal education and economic status of immigrant parents, greater parental involvement with child adjustment processes, and supportive native school peers are enabling factors (Kuset & Gür, 2021). Immigrant parents familiar with the foreign/native language and schools that are more alert to conscious integration/assimilation of non-native students, also bolster the adaptation process (Gromova et al., 2021; Jensen, 2021). Shen (2020) suggested that second-generation immigrant children’s adaptation in the US is positively influenced by parental religiosity, parental educational level, and immigrant family’s socialization with people from other different ethnic groups. Specifically, high academic attainment of immigrant parents is positively linked to immigrant children’s assimilation/adaptation (Cebolla-Boado & Soysal, 2018; Sikora & Pokropek, 2021).

In schools and non-formal education settings, physical education, recreation, and dance-related interventions are gaining prominence for hel** immigrants adjust to new surroundings (Elshahat & Newbold, 2021). There is growing evidence that promoting physical activities and sports can be used as initiatives for immigrant and refugee children and youth for acculturation into a new society (Adamakis, 2022; El Masri et al., 2020, 2021; Elshahat et al., 2020). Marconnot et al. (2021) suggest that the practice of physical activities in the school context can contribute towards generating a more inclusive educational community for immigrant children and adolescents. Physical activities could be a means to mitigate racial/ethnic inequities and promote a sense of belongingness and accept diversities (Barker, 2019; Culp, 2020; Cseplö et al., 2021). Utilizing a unique methodology of ‘get-to-know-you’ arts-based conversational interviews and a three-scene vignette, Middleton et al. (2021) storied the role sports played in immigrant youth’s life journeys and how sports offered a shared sense in acculturative journeys to Canadian host land.

In addition to face-to-face interventions and use of novel methods and techniques, online physical activity interventions to impact affective outcomes are gaining increasing prominence for children in general and immigrant children in particular (de Nocker & Toolan, 2021). Spirituality, related techniques and mindfulness are emerging as a new and prominent concept in physical activity interventions to maximize benefits (Franks, 2021; Johnson & Ginicola, 2021). Knothe & Flores Marti (2018) have suggested for the addition of breath work through yoga within school physical education programs to enhance quality and impact. Lee et al.’s (2020) quasi-experimental study with kindergarteners in Hong Kong found that unstructured play combined with mindfulness interventions improved happiness and aspects of playfulness.

The preceding discussion foregrounds the effectiveness of physical activity-based interventions such as unstructured play, dance, and yoga-meditation for enhancing children’s wellbeing. The effectiveness of similar initiatives for immigrant children to address their complex issues and promote acculturation is also a growing research domain. In line with the global action plan to enhance children’s physical activity for healthier growth (Opstoel et al., 2020; Sallis et al., 2015), a three-arm comparison between recreation (unstructured play), dance, and specialized physical education (yoga-meditation) is required to examine what works for the cohort of immigrant children’s wellness and personal/social development. Happiness is an emotion that indicates the sense of wellbeing, and particularly so in children (Holder & Coleman, 2009; Holder & Klassen, 2010). The following research questions thus emerge, which this study attempts to examine:

-

RQ1: Would there be a significant difference in happiness outcomes of US-based South Asian immigrant children who participant in unstructured play sessions, dance sessions, and yoga-meditation sessions?

-

RQ2: Would there be any significant effects of participant socio-demographics and program compliance variables on outcomes?

-

RQ3: Would it be possible to estimate the extent of post-test outcome changes due to the effective program compliance variables alone (such as attendance, homework), controlling for demographic variations?

This article reports a pre-study or proof-of-concept study comparing the impact of unstructured play, dance sessions, and yoga-meditation sessions delivered and monitored online bi-weekly over a period of 20-weeks on US-based South Asian immigrant children’s happiness outcomes.

2 Method

2.1 Unstructured Play, Dance sessions, Yoga-Meditation sessions cohorts: Socio-demographic Profiles

Table 1 depicts the socio-demographic profiles of comparison group A (unstructured play), comparison group B (dance), and comparison group C (yoga-meditation) US-dwelling South Asian immigrant children at baseline and post-test. Chi-squared tests of significance indicated that there were no significant differences in participant socio-demographics between all the three cohorts at pre-test (T1) (p=.332 –.414) as well as at the post-test stage (p=.344 –.422).

2.2 Recruitment

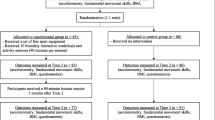

For this three-group comparison pre-study or proof-of-concept study, participants were recruited using snowball sampling through resident associations and informal networks of South Asian immigrants in four US cities: Miami, FL, Chicago, IL, San Francisco, CA, and New York, NY. The four cities were in turn selected based on the possibility of obtaining contacts and reaching out to potential participants. Through this process a list of 189 South Asian immigrants with young children (aged 9-12 years) was obtained. An initial email/social media message was sent to the potential participants briefly describing the study intent, the three programs, and the time commitment required. Inclusion criteria were the willingness to participate, working proficiency (grade 2 level) in English language (parent-reported and child participant confirmed), and no prior or concurrent formal training in dance and/or yoga-meditation. Eventually, the researcher randomized the 131 willing and eligible participants (recruited through snowballing procedures) into three groups (unstructured play, dance, yoga-meditation) using computer generated random numbers. Randomization was masked from the potential participants; participation was voluntary, entailed no monetary costs for the participants, and had an open exit option at any point. Post-test, 114 participants remained with the study. Figure 1 gives details of the flow of participants through each stage.

Informed written consent was obtained from all the immigrant parents and assent was obtained from the child participants. No risks resulting from taking part in the study, were identified. There is no registered funder to report for this submission. The study complies with the independent ethics committee of the University of Mumbai, India and conforms to the norms prescribed by the Declaration of Helsinki, 1975 as amended in 2000, and comparable ethical standards. There are no conflicts of interest to report for this submission. Data are available with the author.

2.3 Measures

Data were collected through online questionnaire administered in English language and through Google form sent on primary caregiver parents’ email addresses accessible through mobile devices. The questionnaire comprised questions on basic demographic details and outcome measures. Program participation (sessions done/attended, homework completed/not completed where applicable) was recorded by instructors and primary caregiver parent respectively onto the Google form. Two child self-report scales were used to assess the outcomes: Children’s Happiness Scale (CHS) and the Happiness and Satisfaction Subscale of the Piers-Harris 2 Self-concept Scale (HASS-PH-2-SCS). Children responded to the scales through their own or their primary caregiver parents’ mobile/computer devices.

The CHS, developed by Morgan (2014) is a 20-item child self-report measure of children’s happiness, with happiness described as a feeling of pleasure or contentment. Children’s views and judgements are taken on feelings of happiness or unhappiness on the day the questionnaire is filled in. Of the 20 statements, ten statements describe unhappy emotions (for instance, I never feel safe, I often get anxious, I am easily depressed). Ten statements describe happy emotions (for instance, Life is good for me at the moment, I am good at learning new things). The scoring is pre-determined wherein next to each statement, a number is mentioned by the scale developers (integer and two decimal spaces). The total of the numbers mentioned against each statement is to be divided by the total number of statements ticked to arrive at the happiness score. The scale developers have mentioned that the highest score is 4.25, median score is 2.88 and the lowest score is 1.68 and have confirmed that the measure has acceptable psychometrics. For the present study: Cronbach α=0.77; item-scale intercorrelation range=0.69–0.78.

Further, the scale has been developed in the UK context and for children in need of care and protection and living in residential institutions. Hence, to assess cross-cultural invariance and applicability for other child cohorts, a single-group confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was undertaken with diagonally weighted least-squares (WLSMV) estimator for non-continuous or ordinal data (Brauer et al., 2023; DiStefano et al., 2019; Li, 2016). The following parameters and corresponding cut-offs were used to indicate a good model-fit: χ2/df≤2, higher p-value; comparative fit index (CFI) >0.95; Tucker-Lewis index (TLI)>0.95; root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA)≤0.06; and, standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR)<0.05) (Tarka, 2017; ** and delivering sessions with children. Program fidelity was ensured through joint development of the respective sessions and continuous liaise between the trainers before and after session delivery to ensure parity and uniformity. The two dance trainers and yoga trainers were paid their professional fees for develo** and delivering the sessions. Technical support of recording participant attendance and preparing MP3 homework assistance files was provided by the researcher. T1 data were collected by the researcher online prior to program commencement and post-test data were collected at the end of the same, 20 weeks later and withing a three-week period.

2.5 Statistical Methods

To examine RQ1, outcome scores of the three groups were compared at baseline and post-test and effect sizes (Hedges’ s g) were calculated. Group x time interactions were assessed through one- and two-way repeated measures ANOVA and mixed design two-way ANOVA. To examine RQ2, linear mixed effects models (fixed and random effects) for both the post-test outcome scores for the three groups were developed. As fixed effects, all the socio-demographic and program compliance variables were taken without interactions. To take into account inter-variable dynamics, as random effects, the interactions between socio-demographic and program compliance variables were taken, thereby considering both the intercept and the slope. Random effects in the models allowed for estimation of the parameters both at the intra and inter-individual levels. Model fit was determined through the following criterion and values: Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), -2 restricted log-likelihood and intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) values. AIC values lower than -2 restricted log likelihood and ICC>0.50 indicated an acceptable model fit. To examine RQ3, Tobit regression models were developed with program variables as explanatory variables and socio-demographics as control variables, with an assessment of models for each outcome with and without socio-demographics. Model-fit statistics and criteria included an overall diagnosis by root mean squared error, sigma, R2, pseudo R2, Akaike information criterion (AIC), and Bayesian information criterion (BIC).

3 Results

The analyses compare happiness outcome scores of the three cohorts at baseline and post-test, examine effects of socio-demographic variables and program compliance on post-test outcome scores, and estimate the extent of post-test changes in happiness outcome scores due to program compliance variables alone, controlling for significant socio-demographics.

3.1 Baseline Comparisons and Post-test Differences

The CHS and HASS-PH-2-SCS outcome scores of all the three cohorts were equal at baseline with no significant differences at the pre-test phase (p=.933 –.999; Hedges’ s g=0.001 –0.02). There were no significant differences in the post-test CHS outcomes of the unstructured play group and dance sessions group (p=.938 –.939; Hedges’ s g=0.02). There were also no significant differences in the post-test HASS-PH-2-SCS outcome scores of the unstructured play and dance cohorts (p=.988 –.994; Hedges’ s g=0.002–0.003). Post-test outcomes of unstructured play and dance cohorts (comparison group A and comparison group B) also showed no significant differences (p=.943 – .984, Hedges’ s g=0.004–0.02). There were significant differences in the post-test CHS outcome scores of the yoga-meditation cohort (p=.029; Hedges’ s g=0.48). There were also significant differences between post-test CHS outcome scores of the unstructured play cohort and yoga-meditation sessions cohort (p=.021; Hedges’ s g=0.54) and between the dance cohort and yoga-meditation cohort (p=.034, Hedges’ s g=0.49). There were significant differences in the post-test HASS-PH-2-SCS outcome scores of the yoga-meditation cohort (p=.002, Hedges’ s g=0.68). There were also significant differences between post-test HASS-PH-2-SCS outcome scores of the unstructured play cohort and yoga-meditation sessions cohort (p=.0041; Hedges’ s g=0.68) and between the dance cohort and yoga-meditation cohort (p=.004; Hedges’ s g=0.66).

3.2 Group x Time Interactions

One-way repeated measures ANOVAs were conducted to compare the CHS and HASS-PH-2-SCS scores of the three groups pre- and post-test. The Mauchly’s tests were non-significant and hence the assumption of sphericity was met. There was a significant main effect of time with respect to the CHS F (1, 83) = 48.92, p=.033, ηp2=0.43, and HASS-PH-2-SCS F (1, 83) = 43.77, p=.044, ηp2=0.45 scores of the yoga-meditation group (Group C). Bonferroni tests also revealed significant differences between the two time points for the yoga-meditation group, with post-test scores being higher. The main effect of time was not significant for the unstructured play group (Group A) and dance sessions group (Group B).

Secondly, two-way repeated measures ANOVAs were conducted with groups (Group A vs Group B; Group A vs Group C; Group B vs Group C) as the first factor and time (pre-test vs post-test) as the second factor to compare the CHS and HASS-PH-2-SCS outcomes. The assumptions of sphericity were met. For both the outcome scores in case of Group A vs Group C and Group B vs Group C, there were significant main effects of group and time and an interaction between group x time. For the CHS outcome, in case of Group A vs Group C, there were significant main effects of group F (1, 74)=46.71, p=.042, ηp2=0.42 and time F (1, 74)=45.77, p=.043, ηp2=0.44 and an interaction between group x time F (1, 74)=43.98, p=.043, ηp2=0.44. For the HASS-PH-2-SCS outcome, in case of Group A vs Group C, there were significant main effects of group F (1, 74)=43.89, p=.043, ηp2=0.42 and time F (1, 74)=48.91, p=0.039, ηp2=0.45, and an interaction between group x time F (1, 74)=48.93, p=.043, ηp2=0.42.

For the CHS outcome, in case of Group B vs Group C, there were significant main effects of group F (1, 76)=43.06, p=.044, ηp2=0.42 and time F (1, 76)=42.91, p=.044, ηp2=0.45 and an interaction between group x time F (1, 76)=45.03, p=.043, ηp2=0.44. For the HASS-PH-2-SCS outcome, in case of Group B vs Group C, there were significant main effects of group F (1, 76)=46.03, p=.039, ηp2=0.42 and time F (1, 76)=44.15, p=.041, ηp2=0.46 and an interaction between group x time F (1, 76)=44.17, p=.040, ηp2=0.48. No significant main effects of group, time and interaction effects were seen in the case of Group A vs Group B. Hence, the yoga-meditation group reported higher CHS and HASS-PH-2-SCS scores at T2 or post-test compared to the unstructured play group and dance group and their own scores at the previous time point or pre-test.

Further, a series of mixed-design two-way ANOVAs were conducted to further investigate group x time interactions on the outcome measures. Results indicated no significant interactions between T1 scores (CHS and HASS-PH-2-SCS) of all the three groups and post-test scores of the unstructured play and dance groups (p=.211 –.513, ηp2=0.10 –0.14). There were significant interactions between post-test outcome scores of the unstructured play group and yoga-meditation group (p=.039–.044, ηp2=0.41–0.45) and the dance group and yoga-meditation group (p=.0381–.044, ηp2=0.42–0.46). There were also significant interactions between pre- and post-test outcome scores of the yoga-meditation group (p=.033–.043, ηp2=0.43–0.49).

Analyses of variance indicated that at the pre- and post-test stages for the unstructured play and dance groups and at the pre-test phase for the yoga-meditation group, the effect of gender as a participant characteristic was significant. Post hoc analyses using Tukey’s HSD indicated that for the unstructured play cohort (Group A), CHS scores were higher for boys at the pre-test phase compared to girls (F (1, 41)=38.99, p=.042, ηp2=0.44) as well as at the post-test stage (F (1, 35)=40.08, p=.043, ηp2=0.43). The pre-test HASS-PH-2-SCS scores of the unstructured play cohort were also higher for boys compared to girls (F (1, 41)=37.95, p=.044, ηp2=0.41) as well as post-test scores (F (1, 35)=41.12, p=.039, ηp2=0.404). Similarly, post hoc analyses using Tukey’s HSD indicated that for the dance sessions cohort (Group B), CHS scores were higher for boys at the pre-test phase compared to girls (F (1, 43)=41.65, p=.039, ηp2=0.406) as well as at the post-test stage (F (1, 37)=40.97, p=.043, ηp2=0.44). The pre-test HASS-PH-2-SCS scores of the dance sessions cohort were also higher for boys compared to girls (F (1, 43)=43.02, p=.043, ηp2=0.45) as well as post-test scores (F (1, 37)=42.05, p=.044, ηp2=0.42).

Post hoc analyses using Tukey’s HSD indicated that for the yoga-meditation cohort (Group C), CHS scores were higher for boys at the pre-test phase compared to girls (F (1, 44)=40.76, p=.042, ηp2=0.44). The pre-test HASS-PH-2-SCS scores of the yoga-meditation cohort were also higher for boys compared to girls (F (1, 39)=39.93, p=.044, ηp2=0.43). All the other main and interaction effects were non-significant (p=.122 –.578, ηp2=0.09 –0.17).

Further, at the post-test stage, when there were significant differences in both the outcomes between the unstructured play cohort and yoga-meditation cohort as well as between the dance sessions cohort and yoga-meditation cohort, the effect of gender continued to be significant. Additionally, the main effects of primary caregiver education, living arrangement, yoga-meditation sessions attended and yoga-meditation homework sessions completed, were significant. Post hoc analyses using Tukey’s HSD indicated that the post-test CHS and HASS-PH-2-SCS scores for the yoga-meditation cohort were higher for girls, immigrant US-dwelling children whose primary caregiver parent had higher formal education (postgraduate degree/professional degree), who lived in a standard family arrangement (with both parents and siblings), who attended 21-40 (>50%) yoga-meditation sessions and who completed 21-40 (>50%) yoga-meditation homework sessions. This was in comparison with boys, children whose primary caregiver parent had lower formal education (high school/college degree), who lived in alternative family set-ups (with one parent, second caregiver and siblings if any or with one parent or caregiver), who attended fewer (0-20 or ≤50%) yoga-meditation sessions and who completed (0-20 or ≤50%) yoga-meditation homework sessions. All the other main effects were non-significant.

3.3 Fixed and Random Effects on Post-test CHS and HASS-PH-2-SCS Scores of the Three Cohorts

Table 2 and table 3 depict the results of the linear mixed models of the fixed and random effects on post-test CHS and HASS-PH-2-SCS scores of the three groups. In the three models in both the tables (table 2 and table 3) respectively, as fixed effects, the following set of variables: origin country, domicile city, age, whether born in domicile city, parent/caregiver immigration duration, gender, religion, economic class, grade of study, primary caregiver parent, primary caregiver parent education and occupation, second caregiver, second caregiver parent education and occupation, siblings, living arrangement, unstructured play/dance/yoga-meditation sessions attended, dance/yoga-meditation homework sessions completed, were entered into the models without interactions. This approach was taken as the CHS and HASS-PH-2-SCS scores were measured for all the three cohorts at both the pre- and post-test stages. As random effects, the interactions between socio-demographics and program-related variables were taken, thereby considering both the intercept and the slope. Estimation of parameters was thus possible at both the intra-group and inter-group levels.

Table 2: model 1 and table 2: model 2 indicated that the said models did not fit the data well as AIC figures were higher than -2 restricted log-likelihood figures, and ICC values were low. Further, in the said models, none of the socio-demographic characteristics or program-related variables significantly impacted post-test CHS outcomes. Hence unstructured play and dance sessions did not impact post-test CHS scores and interactions between participant demographics and play/dance sessions related variables also were not significant. Table 2: model 3 indicated that the said model fitted the data well as the AIC figure was lower than -2 restricted log-likelihood, and ICC value was >0.50. The fixed effects in table 2: model 3 suggested that gender, primary caregiver parent education, living arrangement, yoga-meditation sessions attended, and yoga-meditation homework sessions completed significantly impacted post-test CHS scores of the participants. Further, the random effects or interactions between significant socio-demographics (gender, primary caregiver parent education, living arrangement) and yoga-meditation variables (attendance, homework) were also significant. This indicates that at the post-test stage, the yoga-meditation group participants fared significantly better on the CHS as compared to the unstructured play and dance group participants. Within the yoga-meditation cohort, gender, parental education, and living arrangement significantly contributed to intra-group CHS outcome score differences.

Table 3: model 1 and table 2: model 2 also indicated that the said models did not fit the data well as AIC figures were higher than -2 restricted log-likelihood figures, and ICC values were low. Further, in the said models, none of the socio-demographic characteristics or program-related variables significantly impacted post-test HASS-PH-2-SCS outcomes. Hence unstructured play and dance sessions did not impact post-test HASS-PH-2-SCS scores and interactions between participant demographics and play/dance sessions related variables also were not significant.

Table 3: model 3 indicated that the said model fitted the data well as the AIC figure was lower than -2 restricted log-likelihood, and ICC value was >0.50. The fixed effects in table 3: model 3 suggested that gender, primary caregiver parent education, living arrangement, yoga-meditation sessions attended, and yoga-meditation homework sessions completed significantly impacted post-test HASS-PH-2-SCS scores of the participants. Further, the random effects or interactions between significant socio-demographics (gender, primary caregiver parent education, living arrangement) and yoga-meditation variables (attendance, homework) were also significant. This indicates that at the post-test stage, the yoga-meditation group participants fared significantly better also on the HASS-PH-2-SCS as compared to the unstructured play and dance group participants. Within the yoga-meditation cohort, gender, parental education, and living arrangement significantly contributed to intra group outcome score differences.

3.4 Estimating the Post-test CHS and HASS-PH-2-SCS Scores: Tobit Regression Models

Table 4 and table 5 present the relationship between program related variables (sessions attended, homework completed) and post-test CHS and HASS-PH-2-SCS scores respectively of participants using Tobit regression models (with and without socio-demographics). In table 4 and table 5, RMSE is higher than sigma, which indicates that the Tobit models are accurate. Further, according to the AIC and BIC figures, Tobit models including socio-demographics slightly improved the goodness-of-fit. The predicted CHS and HASS-PH-2-SCS scale scores of immigrant children increased with higher attendance at the yoga-meditation sessions and corresponding homework sessions completed, and this increase was statistically significant. As expected, unstructured play sessions and dance sessions did not significantly impact and predict an estimated increase in post-test CHS and HASS-PH-2-SCS scores. Homework completion of the yoga-meditation sessions tended to have the largest positive impact, followed by attendance and a significant combined impact of both. Socio-demographic characteristics showed that immigrant female children, those whose primary caregiver parents had higher formal education (postgraduate/professional degree) and who lived with both parents and siblings (standard family living arrangement), were likely to have higher post-test CHS and HASS-PH-2-SCS scores compared to their counterparts.

Further, although model goodness-of-fit slightly improved with socio-demographics, the table indicates that this inclusion of socio-demographic characteristics changed the coefficients for the post-test CHS and HASS-PH-2-SCS scores relatively little for both models, as seen in the marginal difference in β coefficients (table 4: model 1, table 4: model 2, table 5: model 1, table 5: model 2). This suggests that the relationship of socio-demographic characteristics and yoga-meditation sessions related variables with the estimated CHS and HASS-PH-2-SCS scores, can be considered independent of each other. Therefore, it would be possible to focus on the model without socio-demographics (table 4: model 1 and table 5: model 1. Table 4: model 1 estimates that CHS scores increased by β=0.458, SE=0.014, p=.030 with increase in attendance at the yoga-meditation sessions, by β=0.469, SE=0.005, p=.008 with increase in corresponding homework sessions completed, and by β=0.011, SE=0.004, p=.004, as a combination effect of yoga-meditation session attendance and homework. Table 5: model 1 estimates that HASS-PH-2-SCS scores increased by β=0.448, SE=0.034, p=.007 with increase in attendance at the yoga-meditation sessions, by β=0.461, SE=0.030, p=.005 with increase in corresponding homework sessions completed, and by β=0.013, SE=0.032, p=.003, as a combination effect of yoga-meditation session attendance and homework.

4 Discussion and Conclusions

Results suggest that participants in the yoga-meditation sessions reported significantly higher scores on the happiness measures compared to unstructured play and dance sessions participants (Hedges’ s g=0.48 –0.68, p=.002–.034). The main effects of time and group x time interactions were significant in case of outcomes of the yoga-meditation cohort. Research on the effectiveness of yoga and meditation for children’s psychological wellbeing in general (Alampay et al., 2020; Felver et al., 2017; Filipe et al., 2021; Janz et al., 2019; Klingbeil et al., 2017; Lawler et al., 2019; Maynard et al., 2017; Quan et al., 2019; Vekety et al., 2021), and happiness outcomes in particular, is corroborated (Guendelman et al., 2017). There is also support for online physical activity interventions for immigrant children (de Nocker & Toolan, 2021). Lower baseline happiness scores ratify the fact that immigrant children need and would benefit from interventions (Dababnah et al., 2021; Haley et al., 2021), and physical activity-based interventions could be a promising domain (Adamakis, 2022; Barker, 2019; Culp, 2020; Cseplö et al., 2021; El Masri et al., 2020, 2021; Elshahat & Newbold, 2021; Elshahat et al., 2020; Marconnot et al., 2021; Middleton et al., 2021).

At the point of no intervention for all the three cohorts, and at the post-test stage for the unstructured play and dance cohorts, CHS and HASS-PH-2-SCS scores were higher for immigrant boys as compared to girls. Some researchers have suggested that immigrant boys find the acculturation process easier and hence better adaptability may mean better wellness and happiness (Qian et al., 2018). Although there was no statistically significant difference in post-test happiness outcomes of the unstructured play and dance cohorts, boys in the said groups continued to report higher post-test scores compared to girls. While this needs a more nuanced and gender-specific examination, research suggesting that boys are more inclined to physical activity (Mauvais-Jarvis et al., 2020; Tcymbal et al., 2020) and more likely to engage in and gain from meaningful outdoor play (Delisle Nyström et al., 2019), finds some support here. The finding that boys in the dance sessions cohort reported better post-test happiness scores is contrary to research contentions that girls are more inclined/motivated to participate and gain from dance interventions (Gramespacher et al., 2020; Silva et al., 2021). Whereas there were no significant changes in pre- and post-test happiness scores of the dance cohort, one speculation for boys outdoing girls in this group is that immigrant boys’ pre-test advantage continued irrespective of the form of physical activity intervention.

Results of the linear mixed effects models suggested that gender, primary caregiver parent education, living arrangement, and program compliance variables (attendance, homework completed) contributed significantly to differences (fixed effects of socio-demographics and program fidelity variables and random effects of interactions) in post-test impact of yoga-meditation sessions. Immigrant girls, whose primary caregiver parent had higher formal education (postgraduate degree/professional degree), who lived in a standard family arrangement (with both parents and siblings), who attended 21-40 (>50%) yoga-meditation sessions and who completed 21-40 (>50%) yoga-meditation homework sessions, were more likely to report higher post-test happiness scores compared to their counterparts. Immigrant girls were at a pre-test disadvantage, but they gained more from yoga-meditation sessions, which falls in line with previous research (Upchurch & Johnson, 2019; Wang et al., 2021). Parental variables were important, with higher formal education of immigrant parents and a standard family living arrangement being enabling factors. Researchers have advocated for the positive correlation between participants’ education levels and gains from yoga-meditation (Ding & Stamatakis, 2014; Park et al., 2015). Results here suggest that in addition to parental inclination-motivation, attitudes, religiosity-spirituality (Bird et al., 2021; Duncan et al., 2009; Padgett et al., 2019), primary caregiver parents’ formal education is positively correlated to immigrant child’s gains from yoga-meditation sessions. The positive connection between immigrant parents’ education levels and gains/benefits for immigrant children is also well elucidated in immigrant literature (see Cebolla-Boado & Soysal, 2018; Gromova et al., 2021; Jensen, 2021; Kuset & Gür, 2021; Shen, 2020; Sikora & Pokropek, 2021) and research on physical activity (Ružbarská et al., 2021; see also Andermo et al., 2021). Standard family living arrangement was another positive moderator for immigrant children’s gains from yoga-meditation sessions. One surmise could be that immigrant children dwelling in secure family set-ups are more positively geared towards the adaptation/acculturation process and draw strength from the family to build psychological resources to do so. A closer examination into concerns of immigrant children in single-parent households, living in non-standard families, and what is additionally required to help them succeed in yoga-meditation sessions, is needed. Further, in line with existing literature, program compliance and fidelity (attendance, homework completed) were strong predictors of the impact of yoga-meditation sessions (Cartwright et al., 2020; Masheder et al., 2020; Schlosser et al., 2019; see also Kelso et al., 2021). The threshold in this case was >50% compliance: participants who attended more than half yoga-meditation sessions and completed more than half corresponding homework sessions reported higher post-test happiness scores compared to their counterparts.

Model-fit statistics and parameters of the Tobit models suggested that it was possible to estimate the extent of post-test changes in CHS and HASS-PH-2-SCS outcomes due to yoga-meditation sessions attended and homework completed alone, controlling for significant socio-demographics. CHS and HASS-PH-2-SCS scores increased by about half an SD with increase in attendance at yoga-meditation sessions and a little more than half with increase in corresponding homework sessions completed. The combination effect of attendance and homework completed was also significant.

Overall, the results of this pre-study suggest that mind-body connection based physical activity interventions are likely to be impactful for immigrant children. A further rigorous investigation could add to the emerging research domain advocating for the insertion of spirituality and mindfulness concepts into physical activity interventions (Franks, 2021; Johnson & Ginicola, 2021; Knothe & Flores Marti, 2018; Lee et al., 2020). This pre-study hints that yoga-meditation sessions have the potential to be useful, diversity-accepting, and inclusive trope for US-dwelling South Asian immigrant children’s psychological wellness and happiness (Barker, 2019; Culp, 2020; Cseplö et al., 2021; Middleton et al., 2021), within the larger global action plan to promote physical activity among children (Opstoel et al., 2020; Sallis et al., 2015).

The study has some of the following limitations that point to directions for further research. Participant recruitment was convenience-based, which indicates selection bias due to non-random procedures. Despite the uniqueness of this sample subset, there is a need to identify rigorous selection strategies for future studies. Both the outcome measures were child self-report, which has acute limitations of reporting bias. Other than grade of study and parental consent, no objective information of reading comprehension levels were available for the cohorts, to ascertain whether the items in the measures were understood. Comparing three groups added an element of robustness to the results, however, the rationale to do so may need firmer argumentation. Most importantly, the study design lacked a control (placebo) group. A follow-up study is needed to show that the reported changes outperform those of a placebo-control intervention.

Only the yoga-meditation cohort reported improved happiness scores post-test, which hints at the redundancy of two comparisons. Moreover, the three-arm design had limited parity as there was no homework or trainer element in the unstructured play sessions, which was a prime factor in the other two programs. Further, the nuances and variations in unstructured play were not adequately captured and primary caregivers were instructed to observe for minimum twice-a-week, though the upper limit was not specified or clarified. This unstructured play for the intervention also did not significantly differ from the unstructured play conducted in the leisure time of the children. There could thus be variations arising from frequency and intensity of children’s play as well as from the type of play. This was not controlled or accounted for, which needs to be looked at for further research.

Homework completion was a strong predictor of program success for dance and yoga-meditation; however, the quality of homework was not assessed. Hence it is impossible to identify the exact threshold of attendance and homework compliance/fidelity that is most effective for the outcomes. Non-participant parental observation and recording of homework completed or otherwise has inherent limitations of bias. Objective reporting through researcher observation or used of augmented reality/artificial intelligence may be required for higher sophistication. Future studies need to take into account immigrant children with special needs, which form a small but significant proportion, and need exclusive care and customized physical activity programs. Qualitative narratives and studies are also needed to map immigrant children’s journeys, affective states, and the nuances of how yoga-meditation sessions can be effective. Further, certain other intervening variables that may bolster or obstruct program participation and impact, not included in the present study need to be controlled or accounted for in later research, including: peer support and factors, sibling variables, neighborhood and other non-formal spaces, and school environment and support.

From a practical application viewpoint, there is some support for yoga-meditation sessions to enhance the happiness outcomes for US-dwelling South Asian immigrant children. The manner in which unstructured play sessions could be augmented and dance sessions can be improvised to meet the desired outcomes, needs to be further investigated. As a specialized physical education activity, yoga-meditation sessions for this unique target group would also need further modifications for boys, immigrant children with less formally educated primary caregiver parents and those living in alternative family set-ups (such as with one parent and/or caregiver). Refinements may possibly include more rigorous physical activities for boys, efforts to promote engagement among less educated primary caregiver parents through awareness sessions or dyadic activities, and more intensive involvement with immigrant children living in alternative/non-conventional families.

References

Abdulla, A., Whipp, P., & Teo, T. (2021). Teaching physical education in ‘paradise’: Activity levels, lesson context and barriers to quality implementation. European Physical Education Review. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X211033696

Adamakis, M. (2022). Promoting physical activity for mental health in a refugee camp: the Skaramagas project. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 56, 115–116. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2021-104636

Aithal, S., Moula, Z., Karkou, V., Karaminis, T., Powell, J., & Makris, S. (2021). A systematic review of the contribution of dance movement psychotherapy towards the well-being of children with autism spectrum disorders. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 719673. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.719673

Alampay, L., Galvez Tan, L., Tuliao, A., Baranek, P., Ofreneo, M., Lopez, G., Fernandez, K., Rockman, P., Villasanta, A., Angangco, T., Freedman, M., Cerswell, L., & Guintu, V. (2020). A pilot randomized controlled trial of a mindfulness program for Filipino children. Mindfulness, 11, 303–316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01124-8

Andermo, S., Rydberg, H., & Norman, Å. (2021). Variations in perceptions of parenting role related to children's physical activity and sedentary behaviours - a qualitative study in a Northern European context. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1550. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11537-7

Barker, D. (2019). In defence of white privilege: physical education teachers’ understandings of their work in culturally diverse schools. Sport, Education and Society, 24(2), 134–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2017.1344123

Bento, G., & Dias, G. (2017). The importance of outdoor play for young children's healthy development. Porto Biomedical Journal, 2(5), 157–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbj.2017.03.003

Bird, A., Russell, S., Pickard, J., Donovan, M., Madsen, M., & Herbert, J. (2021). Parents’ dispositional mindfulness, child conflict discussion, and childhood internalizing difficulties: A preliminary study. Mindfulness, 12, 1624–1638. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-021-01625-5

Brauer, K., Ranger, J., & Ziegler, M. (2023). Confirmatory factor analyses in psychological test adaptation and development: A nontechnical discussion of the WLSMV estimator. Psychological Test Adaptation and Development, 4(1), 4–12. https://doi.org/10.1027/2698-1866/a000034

Britton, W., Lindahl, J., Cooper, D., Canby, N., & Palitsky, R. (2021). Defining and measuring meditation-related adverse effects in mindfulness-based programs. Clinical Psychological Science, 9(6), 1185–1204. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702621996340

Brussoni, M., Lin, Y., Han, C., Janssen, I., Schuurman, N., Boyes, R., Swanlund, D., & Masse, L. (2020). A qualitative investigation of unsupervised outdoor activities for 10- to 13-year-old children: “I like adventuring but I don't like adventuring without being careful”. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 70, 101460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101460

Buck, R., & Turpeinen, I. (2016). Dance matters for boys and fathers. Nordic Journal of Dance, 7(2), 16–27. https://doi.org/10.2478/njd-2016-0011

Cartwright, T., Mason, H., Porter, A., & Pilkington, K. (2020). Yoga practice in the UK: a cross- sectional survey of motivation, health benefits and behaviours. BMJ Open, 10, e031848. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031848

Cebolla-Boado, H., & Soysal, Y. (2018). Educational optimism in China: migrant selectivity or migration experience? Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(13), 2107–2126. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1417825

Cseplö, E., Wagnsson, S., Luguetti, C., & Spaaij, R. (2021). ‘The teacher makes us feel like we are a family’: students from refugee backgrounds’ perceptions of physical education in Swedish schools. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2021.1911980

Culp, B. (2020). Physical education and anti-blackness. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 91(9), 3–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2020.1811618

Dababnah, S., Kim, I., & Shaia, W. (2021). I am so fearful for him: a mixed-methods exploration of stress among caregivers of Black children with autism. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities. https://doi.org/10.1080/20473869.2020.1870418

Deng, Y., Hwang, Y., Layne, T., Yli-Piipari, S. (2021). Parents shape their children’s physical activity during unstructured recess through intrinsic value the children possess. International Journal of Physical Education, Fitness, & Sport, 10(3). https://doi.org/10.34256/ijpefs21311

Delisle Nyström, C., Barnes, J., Blanchette, S., Faulkner, G., Leduc, G., Riazi, N., Tremblay, M., Trudeau, F., & Larouche, R. (2019). Relationships between area-level socioeconomic status and urbanization with active transportation, independent mobility, outdoor time, and physical activity among Canadian children. BMC Public Health, 19, 1082. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7420-y

de Nocker, Y., & Toolan, C. (2021). Using telehealth to provide interventions for children with ASD: a systematic review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1–31. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-021-00278-3

Ding, D., & Stamatakis, E. (2014). Yoga practice in England 1997-2008: prevalence, temporal trends, and correlates of participation. BMC Research Notes, 7, 172. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-7-172

DiStefano, C., McDaniel, H. L., Zhang, L., Shi, D., & Jiang, Z. (2019). Fitting large factor analysis models with ordinal data. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 79(3), 417–436. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164418818242

Doggui, R., Gallant, F., & Bélanger, M. (2021). Parental control and support for physical activity predict adolescents’ moderate to vigorous physical activity over five years. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 18, 43. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-021-01107-w

dos Santos, G., Queiroz, J., Reischak-Oliveira, A., & Rodrigues-Krause, J. (2021). Effects of dancing on physical activity levels of children and adolescents: a systematic review. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 56, 102586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2020.102586

Duncan, L., Coatsworth, J., & Greenberg, M. (2009). A model of mindful parenting: implications for parent-child relationships and prevention research. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 12(3), 255–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-009-0046-3

El Masri, A., Kolt, G., & George, E. (2020). The perceptions, barriers, and enablers to physical activity and minimizing sedentary behaviour among Arab-Australian adults aged 35 to 64 years. Health Promotion Journal of Australia. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpja.345

El Masri, A., Kolt, G., & George, E. (2021). A systematic review of qualitative studies exploring the factors influencing the physical activity levels of Arab migrants. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 18, 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-01056-w

Elshahat, S., & Newbold, K. (2021). Physical activity participation among Arab immigrants and refugees in Western societies: A sco** review. Preventive Medicine Reports, 22, 101365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101365

Elshahat, S., O’Rorke, M., & Adlakha, D. (2020). Built environment correlates of physical activity in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. PLOS ONE, 15(3), e0230454. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230454

Felver, J., Tipsord, J., Morris, M., Racer, K., & Dishion, T. (2017). The effects of mindfulness-based intervention on children’s attention regulation. Journal of Attention Disorders, 21(10), 872–881. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054714548032

Feuerstein, G. (2012). The yoga tradition: Its history, literature, philosophy and practice. SCB Distributors

Filipe, M., Magalhães, S., Veloso, A., Costa, A., Ribeiro, L., Araújo, P., Castro, S., & Limpo, T. (2021). Exploring the effects of meditation techniques used by mindfulness-based programs on the cognitive, social-emotional, and academic skills of children: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 660650. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.660650

Flahive, M., Chuang, Y.-C., & Li, C.-M. (2011). Reliability and validity evidence of the Chinese Piers-Harris Children’s Self-Concept Scale Scores Among Taiwanese children. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 29(3), 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282910380191

Flahive, M., Chuang, Y.-C., & Li, C.-M. (2015). The Multimedia Piers-Harris Children's Self-Concept Scale 2: Its psychometric properties, equivalence with the paper-and-pencil version, and respondent preferences. PLoS ONE, 10(8), Article e0135386. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0135386

Fong Yan, A., Cobley, S., Chan, C., Pappas, E., Nicholson, L., Ward, R., Murdoch, R., Gu, Y., Trevor, B., Vassallo, A., Wewege, M., & Hiller, C. (2018). The effectiveness of dance interventions on physical health outcomes compared to other forms of physical activity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 48(4), 933–951. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0853-5

Francis, G., Farr, W., Mareva, S., & Gibson, J. (2019). Do tangible user interfaces promote social behaviour during free play? A comparison of autistic and typically-develo** children playing with passive and digital construction toys. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 58, 68–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2018.08.005

Franks, H. (2021). Activities to practice and cultivate gratitude in the physical education setting. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 92(1), 36–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2020.1838361

Gang, S. (2005). The use of Piers-Harris Children’s Self-Concept Scale to measure the multidimensional structural model of self-concept for children in second grade (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Iowa.

Goyal, M., Singh, S., Sibinga, E. M., Gould, N., Rowland-Seymour, A., Sharma, R., Berger, Z., Sleicher, D., Maron, D., Shihab, H., Ranasinghe, P., Linn, S., Saha, S., Bass, E., & Haythornthwaite, J. (2014). Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(3), 357–368. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13018

Gramespacher, E., Herrmann, C., Ennigkeit, F., Heim, C., & Seelig, H. (2020). Fachbeitrag:Geschlechtsspezifische Sportsozialisation als Prädiktor motorischer Basiskompetenzen – Ein Mediationsmodell. Motorik, 43(2), 69-77. https://doi.org/10.2378/mot2020.art13d

Grindheim, M., & Grindheim, L. (2021). Dancing as moments of belonging: a phenomenological study exploring dancing as a relevant activity for social and cultural sustainability in early childhood education. Sustainability, 13(14), 8080. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13148080

Gromova, C., Khairutdinova, R., Birman, D., & Kalimullin, A. (2021). Educational practices for immigrant children in elementary schools in Russia. Educational Science, 11, 325. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11070325

Guendelman, S., Medeiros, S., & Rampes, H. (2017). Mindfulness and emotion regulation: Insights from neurobiological, psychological, and clinical studies. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 220. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00220

Haley, J., Kenney, G., Gonzalez, D., & Bernstein, H. (2021). Many immigrant families with children continued to avoid public benefits in 2020, despite facing hardships. Urban Institute.

Holder, M., & Klassen, A. (2010). Temperament and happiness in children. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11, 419–439. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-009-9149-2

Holder, M., & Coleman, B. (2009). The contribution of social relationships to children’s happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being, 10(3), 329–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-007-9083-0

Janz, P., Dawe, S., & Wyllie, M. (2019). Mindfulness-based program embedded within the existing curriculum improves executive functioning and behavior in young children: a waitlist controlled trial. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2052. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02052

Jensen, P. (2021). Immigrants in the classroom and effects on native children. IZA World of Labor, 194v2. https://doi.org/10.15185/izawol.194.v2

Johnson, I., & Ginicola, M. (2021). Quality physical education: The missing ingredient for success. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 92(4), 3–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2021.1886847

Kahn, P., & Kellert, S. (2002). Children and nature: Psychological, socio-cultural, and evolutionary investigations. MIT Press.

Kelley, M. (2005). Review of the Piers-Harris Children’s Self-Concept Scale-Second Edition. Mental Measurements Yearbook, 16.

Kelso, A., Reimers, A., Abu-Omar, K., Wunsch, K., Niessner, C., Wäsche, H., & Demetriou, Y. (2021). Locations of physical activity: where are children, adolescents, and adults physically active? A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), 1240. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18031240

Klingbeil, D., Renshaw, T., Willenbrink, J., Copek, R., Chan, K., Haddock, A., Yassine, J., & Clifton, J. (2017). Mindfulness-based interventions with youth: A comprehensive meta-analysis of group-design studies. Journal of School Psychology, 63, 77–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2017.03.006

Knothe, M., & Flores Martí, I. (2018). Mindfulness in physical education. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 89(8), 35–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2018.1503120

Köngäs, M., Määttä, K., & Uusiautti, S. (2021): Participation in play activities in the children’s peer culture. Early Child Development and Care. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2021.1912743

Kuset, Ş., & Gur, C. (2021). Immigrant mothers with preschool children in northern cyprus and their attitudes towards their children. Journal of Social Studies Education Research, 12(2), 26–53 Retrieved from https://www.learntechlib.org/p/219849/

Latorre Román, P., Pinillos, F., Pantoja Vallejo, A., & Berrios Aguayo, B. (2017). Creativity and physical fitness in primary school-aged children. Pediatrics International, 59, 1194–1199. https://doi.org/10.1111/ped.13391

Lawler, J., Esposito, E., Doyle, C., & Gunnar, M. (2019). A preliminary, randomized-controlled trial of mindfulness and game-based executive function trainings to promote self-regulation in internationally-adopted children. Development and Psychopathology, 31(4), 1513–1525. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579418001190

Lee, R., Lane, S., Tang, A., Leung, C., Kwok, S., Louie, L., Browne, G., & Chan, S. (2020). Effects of an unstructured free play and mindfulness intervention on wellbeing in kindergarten students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(15), 5382. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155382

Lemley, N. (2004). The reliability of the Piers-Harris Children’s Self-Concept Scale, Second Edition. Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 705. Marshall University. http://mds.marshall.edu/etd?utm_source=mds.marshall.edu%2Fetd%2F705&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages

Letton, M., Thom, J., & Ward, R. (2020). The effectiveness of classical ballet training on health-related outcomes: a systematic review. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 17(5), 566–574. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2019-0303

Li, C.-H. (2016). Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: Comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behavior Research Methods, 48(3), 936–949. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-015-0619-7

Loebach, J., Sanches, M., Jaffe, J., & Elton-Marshall, T. (2021). Paving the way for outdoor play: examining socio-environmental barriers to community-based outdoor play. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(7), 3617. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073617

Marconnot, R., Pérez-Corrales, J., Cuenca-Zaldívar, J. N., Güeita-Rodríguez, J., Carrasco-Garrido, P., García-Bravo, C., Solera-Hernández, E., Gómez-Calcerrada, S. G., & Palacios-Ceña, D. (2021). The perspective of physical education teachers in Spain regarding barriers to the practice of physical activity among immigrant children and adolescents: A qualitative study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(11), 5598. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115598

Marron, S., Murphy, F., Pitsia, V., & Scheuer, C. (2021). Inclusion in Physical Education in primary schools in Europe through the lens of an Erasmus+ partnership. Education, 3-13. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2021.2002382

Masheder, J., Fjorback, L., & Parsons, C. (2020). “I am getting something out of this, so I am going to stick with it”: supporting participants’ home practice in Mindfulness-Based Programmes. BMC Psychology, 8, 91. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-020-00453-x

Mauvais-Jarvis, F., Bairey Merz, N., Barnes, P., Brinton, R., Carrero, J., DeMeo, D., De Vries, G., Epperson, C., Govindan, R., Klein, S., Lonardo, A., Maki, P., McCullough, L., Regitz-Zagrosek, V., Regensteiner, J., Rubin, J., Sandberg, K., & Suzuki, A. (2020). Sex and gender: modifiers of health, disease, and medicine. Lancet, 396(10250), 565–582. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31561-0

Maynard, B., Solis, M., Miller, V., & Brendel, K. (2017). Mindfulness-based interventions for improving cognition, academic achievement, behavior, and socioemotional functioning of primary and secondary school students. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 13, 1–144. https://doi.org/10.4073/CSR.2017.5

McAuley, C., & Layte, R. (2012). Exploring the relative influence of family stressors and socio-economic context on children’s happiness and well-being. Child Indicators Research, 5, 523–545. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-012-9153-7

McCrary, J., Redding, E., & Altenmüller, E. (2021). Performing arts as a health resource? An umbrella review of the health impacts of music and dance participation. Plos One, 16(6), e0252956. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252956

Michael, S., Crowther, M., Schmid, B., & Allen, R. (2003). Widowhood and spirituality: co** responses to bereavement. Journal of Women & Aging, 15(2-3), 145–187. https://doi.org/10.1300/J074v15n02_09

Middleton, T., Schinke, R., Habra, B., Lefebvre, D., Coholic, D., & McGannon, K. (2021). The changing meaning of sport during forced immigrant youths' acculturative journeys. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 54, 101917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.101917

Mishra, A., Sk, R., Hs, V., Nagarathna, R., Anand, A., Bhutani, H., Sivapuram, M., Singh, A., & Nagendra, H. (2020). Knowledge, attitude, and practice of yoga in rural and urban India, KAPY 2017: A nationwide cluster sample survey. Medicines, 7(2), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicines7020008

Morgan, R. (2014). The Children’s Happiness Scale. Ofsted. https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/20502/1/The%20Children's%20Happiness%20Scale.pdf

Oliver, W. (2020). Race and racism. Journal of Dance Education, 20(3), 109–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/15290824.2020.1793620

Opstoel, K., Chapelle, L., Prins, F., De Meester, A., Haerens, L., van Tartwijk, J., & De Martelaer, K. (2020). Personal and social development in physical education and sports: A review study. European Physical Education Review, 26(4), 797–813. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X19882054

Ørbæk, T., & Engelsrud, G. (2021). Teaching creative dance in school – a case study from physical education in Norway. Research in Dance Education, 22(3), 321–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/14647893.2020.1798396

Padgett, E., Mahoney, A., Pargament, K., & DeMaris, A. (2019). Marital sanctification and spiritual intimacy predicting married couples’ observed intimacy skills across the transition to parenthood. Religions, 10(3), 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10030177

Park, C., Braun, T., & Siegel, T. (2015). Who practices yoga? A systematic review of demographic, health-related, and psychosocial factors associated with yoga practice. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 38(3), 460–471. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-015-9618-5

Patwardhan, A. (2017). Yoga research and public health: Is research aligned with the stakeholders’ needs? Journal of Primary Care & Community Health, 8, 31–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/2150131916664682

Payne, H., & Costas, B. (2021). Creative dance as experiential learning in state primary education: the potential benefits for children. Journal of Experiential Education, 44(3), 277–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053825920968587

Piers, E. V. (1984). Revised manual for the Piers-Harris Children’ s Self-Concept Scale (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services.

Piers, E. V., & Herzberg, D. S. (2002). Piers-Harris Children's Self-Concept Scale-Second Edition Manual. Western Psychological Services.

Qian, Y., Buchmann, C., & Zhang, Z. (2018). Gender differences in educational adaptation of immigrant-origin youth in the United States. Demographic Research, 38, 1155–1188. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2018.38.39

Quan, L., Yanan, S., Bin, L., & Tingyong, F. (2019). Mindfulness training can improve 3-and 4-year-old children’s attention and executive function. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 51, 324. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1041.2019.00324

Rheaume, K. (2019). Unaccompanied, unnoticed, and undereducated: An analysis of the administrative challenges of educating unaccompanied children in federal custody. Georgetown Immigration Law Journal, 34(1), 159–180 https://www.law.georgetown.edu/immigration-law-journal/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2020/01/GT-GILJ190048.pdf

Ripley, J., Leon, C., Worthington, E., Jr., Berry, J., Davis, E., Smith, A., Atkinson, A., & Sierra, T. (2014). Efficacy of religion-accommodative strategic hope-focused theory applied to couples therapy. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 3(2), 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1037/cfp0000019

Ružbarská, B., Antala, B., Gombár, M., & Tlûcáková, L. (2021). The gender and education of parents as factors that influence their views on physical education. Sustainability, 13, 13708. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413708

Sallis, J., Spoon, C., Cavill, N., Engelberg, J., Gebel, K., Parker, M., Thornton, C., Lou, D., Wilson, A., Cutter, C., & Ding, D. (2015). Co-benefits of designing communities for active living: an exploration of literature. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 12, 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-015-0188-2

Schlosser, M., Sparby, T., Vörös, S., Jones, R., & Marchant, N. L. (2019). Unpleasant meditation-related experiences in regular meditators: Prevalence, predictors, and conceptual considerations. PloS One, 14(5), e0216643. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216643

Schneider, V., & Rohmann, A. (2021). Arts in education: A systematic review of competency outcomes in quasi-experimental and experimental studies. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 623935. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.623935

Shen, Y. (2020). Immigrant parent’s religiosity and the second-generation children’s adaptation. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 25(1), 824–835. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2020.1751218

Sikora, J., & Pokropek, A. (2021). Immigrant optimism or immigrant pragmatism? Linguistic capital, orientation towards science and occupational expectations of adolescent immigrants. Large-scale Assessments in Education, 9, 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40536-021-00101-9

Silva, A., Sá, E., Silva, J., & Pinho, J. (2021). Dance is for all: a social marketing intervention with children and adolescents to reduce prejudice towards boys who dance. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(13), 6861. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18136861

Solomon, T., & Esmaeili, B. (2021). Examining the relationship between mindfulness, personality, and national culture for construction safety. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4998. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094998

Su, L., Lou, X., Zhang, J., **e, G., & Lui, Y. (2002). Norms of the Piers-Harris children's self-concept scale of Chinese urban children. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 16, 31–34.

Tarka, P. (2017). The comparison of estimation methods on the parameter estimates and fit indices in SEM model under 7-point Likert scale. Archives of Data Science, 2(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.5445/KSP/1000058749/10

Tcymbal, A., Andreasyan, D., Whiting, S., Mikkelsen, B., Rakovac, I., & Breda, J. (2020). Prevalence of Physical Inactivity and Sedentary Behavior Among Adults in Armenia. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 157. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00157

Trimboli, C., Parsons, L., Fleay, C., Parsons, D., & Buchanan, A. (2021). A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for 6 - 12-year-old children who have been forcibly displaced. SSM - Mental Health, 1, 100028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmmh.2021.100028.

Upchurch, D., & Johnson, P. (2019). Gender differences in prevalence, patterns, purposes, and perceived benefits of meditation practices in the United States. Journal of Women's Health, 28(2), 135–142. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2018.7178

Vekety, B., Logemann, H., & Takacs, Z. (2021). The effect of mindfulness-based interventions on inattentive and hyperactive–impulsive behavior in childhood: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 45(2), 133–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025420958192

Wang, Y., Chen, Y., Sun, Y., Zhang, K., Wang, N., Sun, Y., Lin, X., Wang, J., & Luo, F. (2021). Gender differences in the benefits of meditation training on attentional blink. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01891-5

Weinberg, D., Stevens, G. W., Bucksch, J., Inchley, J., & de Looze, M. (2019). Do country-level environmental factors explain cross-national variation in adolescent physical activity? A multilevel study in 29 European countries. BMC Public Health, 19, 680. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6908-9

Wieland, L., Cramer, H., Lauche, R., Verstappen, A., Parker, E., & Pilkington, K. (2021). Evidence on yoga for health: A bibliometric analysis of systematic reviews. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 60, 102746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2021.102746

**a, Y., & Yang, Y. (2019). RMSEA, CFI, and TLI in structural equation modeling with ordered categorical data: The story they tell depends on the estimation methods. Behavior Research Methods, 51, 409–428. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-018-1055-2

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Informed Consent

Informed written consent was obtained from all the immigrant parents and assent was obtained from the child participants. No risks resulting from taking part in the study, were identified. There is no registered funder to report for this submission. The study complies with the independent ethics committee of the University of Mumbai, India and conforms to the norms prescribed by the Declaration of Helsinki, 1975 as amended in 2000, and comparable ethical standards. There are no conflicts of interest to report for this submission. Data are available with the author. Samta P Pandya conceptualized the study, collected and analyzed the data, and prepared and revised the manuscript for submission.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Pandya, S.P. Unstructured play activities, dance lessons, and yoga-meditation classes: What makes immigrant South Asian US-dwelling children happier?. Int J Appl Posit Psychol 8, 637–675 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-023-00111-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-023-00111-8