Abstract

This study investigates the factors influencing university students’ online learning engagement from three distinct aspects, namely, behavioural, cognitive and emotional engagement. A comparison is drawn from university students in Asia who embraced online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. An online survey was conducted on 495 university students in Mainland China, Hong Kong and Malaysia during the surge of the COVID-19 Omicron variant, which was considered more infectious but less deadly than previous variants. A consistent positive relationship between Satisfaction and Academic Performance is found in all the regions. Malaysia presents a unique situation as compared to Mainland China and Hong Kong whereby no association was found between Social Context and Online communication towards Student Engagement. The novelty of this study is attributed to the integration of Social Presence Theory in Student Engagement through the nature of online learning as a co** strategy to halt the spread of COVID-19 during the Omicron variant surge.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic, teachers have utilised online methods to impart knowledge and deliver lessons to students. One of the greatest challenges for teachers is not delivering their lectures online, but how to sustain students’ attention in the online class (Wut & Xu, 2021). In the post-pandemic period, online learning mode has become one of the options in higher education (Wut et al., 2022a, 2022b). The online mode offers flexibility with the support of developed technology support. However, the success of online teaching depends on the engagement of students (Orlowski et al., 2021). The factor that affects specific engagement types remains unknown, and the existing literature in this area suffers some deficiencies. This study endeavours to close this research gap by investigating various factors affecting behavioural engagement, emotional engagement and cognitive engagement from the perspective of social presence theory in three regions: Mainland China, Hong Kong and Malaysia. The rationale for selecting the universities from these regions stemmed from the unique general similarities and the detailed divergence among the respective education curriculum, learning context and online learning infrastructure. University students in Hong Kong mainly used Blackboard or Moodle as their learning management system. They pursue four years program like students in China. In terms of education curriculum, Hong Kong is the most internationalized which is influenced by British and United States. As Hong Kong is a special administration regime under China, both share a similar standard of university entrance. Also, these two regions have a similar culture which shapes the social presence of the students and likewise their engagement. As such, this study offers better generalization by including university students from these two regions. As for Malaysia, its’ education system follows the British education system which is also being adopted in Hong Kong. Some universities in China use Skype online platform or XuetangX to communicate with their students. There are various online learning platforms in Malaysia including Internexia, Pukunui and eLearningMinds. Adding on, at the university level, these three Asia regions have much similarities in terms of online learning infrastructure and it makes a good comparison between them.

At the beginning of the year 2022, the Omicron virus, the latest COVID-19 variant has affected almost every part of the world. Most of the universities in the affected area have been adopting full online teaching at that time. In Mainland China, some of the university students reverted to online learning mode or hybrid learning mode from face-to-face mode. University students in Hong Kong changed to fully online learning mode from hybrid learning mode. In hybrid learning mode, students may attend the class either face to face or online depending on the circumstances (Dodwell, 2022).

In Malaysia, the first Omicron case was detected at the end of December 2021, and the number of Omicron cases peaked in February 2022. The Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE) in Malaysia has taken a different approach to handle tertiary institutions. The MOHE of Malaysia leaves the decision of reopening the universities and colleges to the intuitions themselves. The rationale for such a decision is stemmed from three reasons. First, the vaccination rate in Malaysia had achieved 83.9%. Second, Malaysia is more prepared in this new wave of COVID-19 variant after two years of battling with the virus since March 2020. Third, different institutions have different capabilities to administering online or face-to-face classes. With such autonomy given to tertiary institutions, different universities and colleges have practiced non-uniform approaches to holding classes. Following each institution’s situational analysis, the three main modes are face-to-face, hybrid and online (The Vibes, February 2022).

Unlike in the years 2020 and 2021, students and teachers in the year 2022 have become more familiar with the connectivity tools and online learning platforms to withstand the surge of the Omicron variant. In fact, technology is not the main issue in online learning (Wut & Lee, 2021). Other prominent factors lead to effective online learning, such as communication and interpersonal connection between students (Kahn et al., 2017) and level of information transpired (Conrad, Eng, Caron, Shkurska, Skerrett, & Sundararajan, 2022).

Salas-Pilco et al. (2022) stated that student engagement is one of the crucial criteria in online learning. Student engagement is linked with their satisfaction, which ultimately affects their academic development and well-being (Bowden, 2022). Unlike traditional face-to-face classes, online learning may limit the perception of involvement. On the contrary, some students could be more participative in the online learning setting through chat rooms than in face-to-face classes (Wut & Xu, 2021). There is a literature gap that how virtual learning environment creates “virtual presence” affecting student engagement at the end. Perceived sociability and sense of community was associated with student engagement in flipped classroom (Karaoglan-Yilmaz & Yilmaz, 2022a). Thus, knowing the factors that affect student participation in online learning is deemed an urgent and timely agenda at this juncture.

Literature review

Social presence theory

Presence is once defined as being in a place physically (Biocca, 1997) or simply physical presence. In online learning, teachers and students meet in the virtual environment. Thus, presence could be represented by a sense of consciousness or a sense of being in a virtual classroom by means of telecommunication tools (Fan et al., 2022). We may treat that type of presence as telepresence.

Additionally, presence can be described from a social perspective. Social presence refers to ‘the minimum level of presence that occurs when one feel that a behaviour or sensory experience which indicates the presence of other intelligence’ (Biocca, 1997). Social presence means people perceive the others in a remote setting to build a relationship (Garrison, 2007; Pavlou et al., 2007). Social presence can affect communication quality (Chang & Hsu, 2016) and can serve as a medium through which people exchange ideas. Face-to-face communication is usually the most effective communication medium, whereas electronic communication offers lower efficiency (Gefen & Straub, 2004). When people meet each other via computer technology, the level of social presence depends on the online tools. If people could see and talk to each other, then the social presence could be high and vice-versa (Gefen & Straub, 2004).

Social presence can affect information sharing behaviour, and it is composed of three dimensions, namely, ‘awareness, cognitive social presence and affective social presence’ (Shen & Khalifa, 2008, p. 723). Awareness may promote personal interactions (Chang & Hus, 2016). Cognitive social presence refers to ‘the extent to which a user is able to confirm meaning about his relationship with others’ (Shen & Khalifa, 2008, p. 730). Students know one another easily by working as a team. They belong to the same collective group and have a common understanding. Affective social presence refers to the ‘level of emotional connection amongst students’ (Shen & Khalifa, 2008, 730). This construct has been tested to improve information exchange (Shen et al., 2010). However, given the remoteness of students in online environments, teachers cannot easily tell whether their students are interested in what teachers are saying. A feeling of isolation may be formed because of the lack of non-verbal or informal communication (Wut et al., 2022a, 2022b). The dimensions of social presence suggested by Garrison (2007) are effective communication, open communication and group cohesion.

Social presence is represented in three dimensions: social context, online communication and interactivity. The dimension of social context is similar to cognitive social presence or group cohesion. It represents a form of personal communication and is suitable to connect friends and family members (Leong, 2011). The dimension of online communication is similar to affective social presence or open communication, in which people freely express their ideas. Such communication transmits feelings and emotions. The dimension of interactivity is similar to awareness defined by Shen and Khalifa (2008) or effective communication. It deals with efficiency of personal interaction. It is associated with whether the online learning environment is user friendly.

Student engagement

Scholars have investigated student engagement (Quin, 2017; Bowden, 2022). Student engagement is also referred to as student participation in the learning process, such that students are expected to fulfil learning outcomes set at the beginning of the course. Student engagement is an important issue in online learning (Karaoglan-Yilmaz & Yilmaz, 2022b).

During face-to-face class, students are more likely to participate in the class due to their physical presence. However, university students attend lectures online during pandemics. In such cases, they are easily distracted by many other matters in their home environment. Teachers use various online tools to provide a positive learning environment in online setting (Marques et al., 2020). Others provide instant feedback and use more group activities (Chakraborty & Nafukho, 2014) that are similar to those used in face-to-face setting.

Other factors such as situational interest, computer self-efficacy and self-regulation affect student engagement. Situational interest is distance education in the study (Sun & Rueda, 2012). However, no control group is compared with the experimental group and the results may not be fully validated. In addition, course design has been found that related to student engagement as well (Su & Guo, 2021). There are three dimensions of engagement: “behavioural engagement, emotional engagement and cognitive engagement (Bowden, 2022, 1000).” Examples of behavioural engagement are attendance, class participation and discussion. Joy or excitement are emotional engagement. Students use of their mental resources is cognitive engagement (Bowden, 2022). Thus, actual student participation in activities is measured in behavioural engagement. Students’ feelings and attitudes are reflected in emotional engagement. In-depth and extra efforts used are taken as cognitive engagement (Fredricks et al., 2004). Most previous studies were conducted on behavioural engagement, whereas only a few have been conducted on emotional and cognitive engagement (El-Sayad et al., 2021).

Student satisfaction

Different factors affect student satisfaction in China during online learning: learner–learner interactions, learner–content interaction, learner–instructor interaction, system quality, course design and self-discipline. System quality refers to the online learning system. Course design refers to the planning and design of the course content. Students who have self-discipline could resolve conflicts between short-term goal and long-term goal. For example, to excel in academic performance is a long-term goal, whereas enjoying summer is a short-term goal. Students can strike a balance between short-term and long-term goals (Su & Guo, 2021).

Social presence affects student satisfaction positively (Leong, 2011; Ooi et al., 2018), and cognitive adsorption serves as a mediator. Cognitive adsorption is associated with flow and cognitive engagement. It has been defined as intensive involvement with information technology in online learning (Leong, 2011). By contrast, the direct effect of social presence on satisfaction was found not significant in an online setting (Orlowski et al., 2021). There is a literature gap that what happens on the mechanism of the relationship. Moreover, intrinsic motivation influences satisfaction (Leong, 2011).

Social presence theory was used as a theoretical foundation underpinning our study. It assumes that social presence influences the recipients’ understanding of the senders’ material (Miranda & Saunders, 2003). In our context, the recipients are university students and the senders are teachers. If students could understand the teachers’ material, then they would be satisfied; therefore, their academic performance will be improved. Student engagement is proposed to be the mediator in the study.

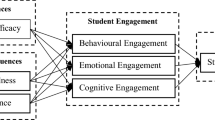

Figure 1 shows the theoretical framework of our research.

Social presence consists of three components, namely, social context, online communication and interactivity. Social presence influences the multi-dimensions of student engagement, namely, behavioural engagement, emotional engagement and cognitive engagement. In turn, student engagement affects students’ learning outcomes.

Association between social presence and student engagement

Social presence has a relationship with student engagement. However, social presence was presented as a single construct. Further research was suggested to address which component of social presence is a major determinant of student engagement. Social presence was related to emotional engagement and cognitive engagement in wine and spirits courses, respectively (Orlowski et al., 2021).

Association between student engagement and learning outcomes

Studies have been conducted on the relationship between student engagement and satisfaction. Scholars found that they have a high correlation between student engagement and satisfaction in flipped classroom learning and online setting, respectively (Alsowat, 2016; Orlowski et al., 2021; Karaoglan-Yilmaz & Yilmaz, 2022a). In a study on a flipped classroom of English language subject, students in the experimental group had a significant relationship between student engagement and satisfaction (Alsowat, 2016). In wine and spirits courses, emotional engagement and cognitive engagement were associated with course satisfaction. Students enjoyed the content and interacted with classmates and instructors (Orlowski et al., 2021). It was found that student engagement was associated with student satisfaction in a university computing course running flipped class mode (Karaoglan-Yilmaz & Yilmaz, 2022a).

Studies have been conducted on the relationship between student satisfaction and performance. Generally, student satisfaction and student performance are two common outcomes in the field of education research. Student satisfaction is measured using a student feedback form, which is common in higher education. Student performance can be obtained from their grades. A new format was used by combining lecture and laboratory in health science courses. Both students and instructors gave positive responses regarding the change. Moreover, grades were improved and less failure cases were recorded compared with the control class (Finn et al., 2017). Thus, an association exists between student performance and their satisfaction on the online course (Chitushev et al., 2014).

Development of hypotheses and research model

Social presence positively influences brand engagement through a corporate social media site (Osei-Frimpong & McLean, 2018). Similarly, social presence likely positively affects students’ engagement through an institution’s online learning platform. Thus, studying their relationship in a critical and sophisticated manner is beneficial. Which component of social presence (social context, online communication and interactivity) affects behavioural engagement, emotional engagement and cognitive engagement in a larger extend manner? Fig. 2 presents our research model.

As mentioned in student engagement section, students in online learning who work as teams to accomplish an exercise are used to being involved in the lesson. For example, students are divided into several teams to answer questions from teachers using Kahoot, Poll Everywhere or other online tools. During the group activity, students get to know each other better. They help each other answer questions from their teachers. Then they tend to participate more. The previous literature has not yet examined the relationship between social context and engagement (Wut & Xu, 2021). Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1

Social context influences behavioural engagement positively.

Students express their feelings more in a group with which they have common understanding. The group is small in size so that students can fully express their views. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2

Social context influences emotional engagement positively.

Students are more interested in the subject if the responses from their instructor and fellow classmates are quick enough for students gaining more understanding on the material. They feel less bored and want to learn more. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3

Social context influences cognitive engagement positively.

Students have more emotional connection with one another and their attendance or participation in class will be increased. The previous results found that university learners’ Learning Management System acceptance was associated with their sense of community and engagement in blended learning (Ustun et al., 2021). Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4

Online communication influences behavioural engagement positively.

Students have more emotional connections with one another. They share similar problems and concerns. Thus, students share more about their feelings. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5

Online communication influences emotional engagement positively.

When the students have more emotional connection with one another, they are then intrinsically motivated to learn more. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 6

Online communication influences cognitive engagement positively.

The online learning environment is user-friendly and easy to use. Higher efficiency of online environment among student interaction fosters student participation in class. Interaction among students affected student engagement through transaction distance (Karaoglan-Yilmaz et al., 2022). Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 7

Interactivity influences behavioural engagement positively.

Similarly, higher efficiency of online environment on student interaction and student tends to encourage students to share their opinions. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 8

Interactivity influences emotional engagement positively.

Higher efficiency in student interaction encourages students to learn easily. As a result, they become devoted to the subject. Thus, we have the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 9

Interactivity context influences cognitive engagement positively.

Little is known about which component of student engagement is the main determinant of student satisfaction. When students participate in class often, they should enjoy the course. Thus, we have the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 10

Behavioural engagement affects student satisfaction positively.

Students express their feelings more during the session and they have a higher satisfaction level. Thus, we have the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 11

Emotional engagement affects student satisfaction positively.

Students immerse themselves in the subject material and they master the course. At the end of the course, students are more satisfied. Thus, we have the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 12

Cognitive engagement affects student satisfaction positively.

When students feel satisfied with their studies, they have better academic performance (Finn et al., 2017). Thus, we have the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 13

Student satisfaction affects their academic performance positively.

Research methodology

A quantitative method using questionnaire approach was employed. The convenience sampling technique was used given the homogeneity of the university student population. Efforts had been made to ensure the gender and level of study are the same on the area compared with other higher education institutions. More female students participated than male students. The number of students in Year 1 to Year 3 is about the same, but the number of students in Year four were less, perhaps due to drop** out of students.

Partial least squares structural equation modelling was used in the analysis because the research aim is predictive and explanation of variance (Shmueli et al., 2019). The research model involved some latent variables. The model is complex with many indicators; hence, partial least squares method was recommended (Hair et al., 2019).

Multi-group analysis is used to compare students from China, Hong Kong and Malaysia. The permutation algorithm allows researchers to decide whether pre-defined groups are significantly different from one another. Measurement invariance was assessed to ensure that multi-group analysis was meaningful.

Measurement

All the questionnaire items were adopted from established scales. Social presence is assessed by using three dimensions: social context; online communication and interactivity. For example, one of the items of social context is that Online Learning Environment provides an informal and casual way to communicate. “Language used in OLE is stimulating” is an item of online communication. “Language used in OLE is stimulating” is an item of interactivity (Leong, 2011). Student engagement has three dimensions: behavioural engagement; emotional engagement and cognitive engagement (Sun & Rueda, 2012). Reverse scale items have been used to detect any non-normal responses. For social context, SC3 and SC6 are using reverse scales. As for online communication, OC3 adopts a reverse scale while the last item of interactivity, NT5 is measured using a reverse scale. BE2 and BE3 are the items measured with reverse scales for behavioral. The last item of emotional engagement, EE6 is also measured with a reverse scale.Student satisfaction measurement items are adopted from Kuo et al. (2014) and academic performance is based on the scale by Yu (2010).

Some of the measurement items are modified to suit the current research objectives. To improve understanding and facilitate the answering process, the language used in the scale is adapted to meet the actual situation of the online learning environment, making use of common colloquialisms. Table 1 shows the survey instruments with modifications used.

Data collection

A survey was conducted using an online format in April 2022 amongst university students in Asia, specifically, Mainland China, Hong Kong and Malaysia, to test the proposed hypotheses developed on the basis of social presence theory. Ethics approval was obtained. The survey was conducted during the surge of the Omicron variant. The target respondents were university students who used online learning most of the time in the year 2022 before they were surveyed. 495 respondents were included in our sample. The majority of the respondents is from China (53.9%), followed by Hong Kong (30%) and Malaysia (15%). The female university students made up the majority of the respondents, i.e., 60.6% while the male university students stand at 39.4%. Of the respondents, 29.7% were in year 1, 28.9% were in year 2, 28.1% were in year 3 and 12.5% were in year 4. Half of the respondents study business, whereas the rest study Social Science, Science, Engineering, Humanities and Health Studies (Table 2).

SmartPLS 4.0 statistical software was used as the analytical tool in this study. PLS-SEM is used when the research objective is theory development and explanation of variance, such as the subject of this research. There are many indicators in the model. Given a 5% significance level with a minimum path coefficient from 0.11 to 0.2, the minimum sample size level of 155 was recommended (Hair et al., 2019). The current study successfully obtained 495 responses which surpassed the recommended sample size. PLS-SEM was used in this research due to the complexity of the research model that comes with multiple constructs and items.

Same respondents were asked about the information of dependent and independent variables. In order to find any common method bias, Harman single-factor test was used (Rodriguez-Ardura & Meseguer-Artola, 2020). The total variance explained is 24.53%, which is well below the 50% threshold. Therefore, common method bias is not a problem in this research.

Findings

Assessment of measurement model

Two items’ loadings from social context, behavioural engagement, one item’s loading from online communication and interactivity, and three items’ loading from cognitive engagement are below 0.708 (Table 3). Those items were excluded for further analysis. The fourth item of social context was marginally lower than the threshold and retained. All the constructs meet convergent validity requirements which are between 0.70 and 0.95. The Cronbach’s alpha of behavioural engagement (0.633), which was slightly below the threshold (i.e. 0.7).

Table 3 shows the constructs’ reflective measurement model assessment. All the relevant average variance extracted values were larger than 0.50. Convergent validity requirement was fulfilled. The HTMT values were all less than 0.90 and no problem on discriminant validity (Table 4). Thus, the structural model was assessed subsequently.

The structural model was supported with satisfactory results (Fig. 3).

In assessing our model’s explanatory power, the coefficient of determination was used. The adjusted R2 values of behavioural engagement, emotional engagement, cognitive engagement, satisfaction and academic performance were 0.385, 0.405, 0.340, 0.711 and 0.340, respectively; thus, 34.0 to 71.1% of the variances were explained. Secondly, all f2 effect sizes of predictor construct ranged from 0.015 to 0.789, indicating small to large effect sizes on the dependent construct.

In assessing our model’s predictive power, the Q2 statistics was used. The Q2 values ranged from 0.187 to 0.477, indicating small to medium predictive relevance of the path model. Moreover, PLS predict procedure was used. First, all Q2 predict values of all our indicators are from 0.136 to 0.437 which greater than zero. Second, the mean absolute values (MAE) were compared to linear regression benchmark (LM). Thirteen mean absolute values were smaller than LM values, 10 were larger than LM values. Thus, our model has medium predictive power (Hair et al., 2022).

Results of hypothesis testing and path analysis

Hypothesis test results and direct path analysis

Hypotheses 1, 2 and 3 proposed a relationship between social context and student engagement in online learning. The hypotheses were supported with p values < 0.01 (Table 5). Thus, social context positively influences student engagement in online learning. In particular, the strongest path was between social context and cognitive engagement.

Hypotheses 4, 5 and 6 measured the association between online communication and student engagement in online learning. A positive and significant relationship was confirmed with the p value < 0.05 (Table 5). In particular, the strongest path was between online communication and cognitive engagement.

Hypotheses 7, 8 and 9 proposed a relationship between interactivity and student engagement in online learning. The relationship was verified (Table 5). Thus, an association exists between interactivity and student engagement in online learning. In particular, the strongest path was between interactivity and behavioral engagement.

Hypotheses 10, 11 and 12 proposed that student Engagement and satisfaction are related. This hypotheses were supported with p values < 0.01. In particular, the strongest path was between satisfaction and emotional engagement.

Hypothesis 13 proposed the relationship between satisfaction and academic performance. The hypothesis was supported as well with p value < 0.001 (Table 5).

Multi-group analysis

Examining the results according to the geographical regions such as Mainland China, Hong Kong and Malaysia would provide meaningful insights. An association was found between satisfaction and academic performance in all regions. However, no association was found between social context and student engagement among Malaysian students. An association was found between social context and behavioural engagement among university students in China. By contrast, associations are found between social context and emotional engagement and cognitive engagement, respectively, among university students in Hong Kong (Tables 6, 7 & 8). An association was found between interactivity and student engagement of university students in Malaysia and China. However, no association was found between interactivity and cognitive engagement of university students in Hong Kong. An association was found between student engagement and satisfaction of university students in Hong Kong and Malaysia. Lastly, no association was found between behavioural engagement and satisfaction of students in China (Tables 6, 7 and 8).

Measurement invariance of composite models procedure was followed, and identical indicators were used. Same data treatment and algorithm setting per each group satisfy configural invariance precondition. In step 2, the composite scores did not differ across three groups. Partial measurement invariance was found as mean values and variances are not the same. Therefore, researchers can compare standardised coefficients of the structural model for different groups (Hair et al., 2022).

Hong Kong students’ cognitive and emotional engagement were affected by social context whereas Malaysian students did not have same associations. Hong Kong students’ behavioural engagement was affected by online communication whereas Malaysian students also did not have the same association. In contrast, Malaysian students’ cognitive engagement was affected by interactivity whereas Hong Kong students did not have the same association (Table 6).

China students’ cognitive and emotional engagement were affected by online communication whereas Malaysian students did not have the same associations. China students’ behavioural engagement was affected by social context whereas Malaysian students did not have the same association (Table 7).

Hong Kong students’ cognitive and emotional engagement were rather affected by social context when compared to China students. China students’ behavioural engagement would be affected by social context when compared to Hong Kong students. Hong Kong students’ behavioural engagement was affected by online communication when compared to China students. China students’ emotional and cognitive engagement were affected by online communication when compared to Hong Kong students (Table 8).

Discussion

Our research model is confirmed by our empirical data, and all the hypotheses are supported by the pooled data (Table 5). On the basis of the magnitude of path coefficients, interactivity is the main determinant on student engagement compared with social context and online communication. Regarding association between student engagement and satisfaction, emotional engagement is the key determinant of student satisfaction. Our result is similar to that of Orlowski (2021) who explored emotional and cognitive engagement. We found an association between behavioural engagement and satisfaction, but Orlowski did not. The difference is probably due to the course nature. Our study is on a regular academic course. Students who participate more generally have greater satisfaction. Orlowski’s study was conducted in a laboratory setting, and some students may not like the practice or have an interest in laboratory work.

A detailed investigation in terms of country/region from multi-group analysis reveals interesting findings (Tables 6, 7 & 8). Students in Hong Kong are in smaller classes (e.g. usually less than 50). They do not get bored easily and are more involved in the class. Thus, the effect of social context on behavioural engagement is not significant on Hong Kong students according to Social presence theory (Shen et al., 2010). By contrast, if the class size is comparatively large like in China, the effect of online activity may be larger. Students are likely to participate more in class.

Teachers in Hong Kong use online icebreaker activities to let students get to know one another through online collaborative learning (Ng et al., 2022). Thus, their attendance can be improved. However, it might not have effect on emotional and cognitive engagement. By contrast, some online activities could elicit more emotional and cognitive engagement on university students in China (Table 8).

The results illustrated in Tables 6 and 7 suggest that Malaysian students show a unique trend compared with Mainland China and Hong Kong students. Hypotheses 1 to 6 are found to be non-significant. This finding indicates that social context and online communication do not influence Malaysian students’ behavioural engagement, emotional engagement and cognitive engagement. For the current research, social context measures the cognitive social presence by the definition of the extent to which a user is able to confirm the meaning of his or her relationship with others in the same collective group. Moreover, cognitive social presence represents a form of personal communication that is suitable for connecting with friends and family (Leong, 2011). According to the Malaysian students’ samples, this batch of students was admitted to the tertiary institutions in May 2020 after they obtained their high school results in April 2020. The Malaysian Government ordered a few phases of lockdown and movement control in March 2020, and until more recently, the lockdown was replaced by stages of opening, followed by the national recovery phase. Hence, the students are totally new to the virtual online learning system, and they do not know their coursemates or other learners in the online learning platforms. Under this condition, establishing social presence without knowing one another prior to joining of online learning platforms is extremely difficult according to the social presence theory (Shen et al., 2010). As such, social context and online communication are found insignificant for the three dimensions of students’ engagement. In addition, the non-uniform practice of the opening of tertiary institutions and modes of study have further contributed to the non-significant findings. Apart from the conditional reasons, the small sample size has demonstrated an enormous influence on the significance of the results. Owing to these circumstances, the Malaysian students’ results deviate from the Mainland China and Hong Kong samples.

An association exists between interactivity and student engagement among all countries/regions. This association indicates that other factors affect the cognitive engagement of university students in Hong Kong. Echoed by Fredricks et al. (2004), in-depth and extra efforts used are taken in cognitive engagement. Samples from Hong Kong are all from the self-finance sector institutions. Students are less motivated and passive comparatively to the funded universities. The situation is even worse when the courses are in online format. Although there is significant association has been found between cognitive engagement and satisfaction for Hong Kong students, the strength of the relationship is not strong. It is due to the students rely on the memory of academic concepts and reproduced in the tests and examination. In addition, less person-to-person interaction during online learning is one valid reason (Wut & Xu, 2021).

During the Omicron surge, student and teachers were used with technologies. Some models such as Technology Acceptance Model might not be applicable. On the contrary, human interaction becomes more important especially in online environment. Social presence theory was supported in our study. Social presence components, social context, online communication and interactivity affect multi-dimensions of student engagement, namely, behavioural engagement, emotional engagement and cognitive engagement.

Practical implications

Class size is one of the factors affecting behavioural engagement. Online learning tools would be more effective in large classes. Behavioural and emotional engagement are slightly easier achieved. More efforts are needed to improve cognitive engagement, especially for less active students. Providing a good online learning environment is more effective for Hong Kong students. Moreover, we need to pay attention to the language used in online learning environment and interactivity for students in China. Last but not the least, interactivity is the key to cognitive engagement.

In the Malaysian context, learning in an online platform can be optimised when teaching methods focus on student engagement with course content and student–student interactivity. Following the results obtained, teachers must keep in mind that practical applicability of technological tools such as breakout rooms, virtual whiteboard discussions and online communication could potentially benefit students. In fact, moving forward, this approach serves the best interest of student learning under this modality. While teachers strive to optimise online learning outcomes for students, it is imperative that social learning through engagement and interactivity be considered the utmost important element to be implemented in the new teaching methods in the virtual learning environment.

Further research directions

The study is cross-sectional in nature and uses self-reported survey. Using observation could add more insights on the study. Thus, a longitudinal study is recommended because delay of the timing of independent variables and outcome variables is inevitable. For example, when students are more engaged during class, they become more satisfied towards the end of the semester. Academic performance is recorded subsequently. More countries could be included in the survey like European countries and United States. In addition, students were mainly from business courses. Future research could explore the students from other disciplines such as engineering courses. Finally, a follow-up qualitative study may be considered to investigate the non-significant results.

Conclusion

Past literature advocates a holistic approach on the multi-dimension nature of student engagement. Our study advances the knowledge of student engagement in tertiary education using online learning during the surge of the COVID-19 Omicron variant. The novelty of this study is attributed to the integration of Social Presence Theory in Student Engagement through the nature of online learning as a co** strategy to halt the spread of COVID-19 during the Omicron variant surge.

An association was found between satisfaction and academic performance in all regions.

Interactivity associates with student engagement in general. The exception is that interactivity is not associated with cognitive engagement in Hong Kong. Student engagement associates with satisfaction. The exception is that behavioural engagement is not associated with satisfaction in China. Malaysia presents a unique situation as compared to Mainland China and Hong Kong whereby no association was found between Social Context and Online communication towards Student Engagement. In addition, no relationship was found between online communication and student engagement in Malaysia. In conclusion, findings of our study provides empirical support to the previous qualitative result. Practical suggestions for online teaching were proposed.

References

Alsowat, H. (2016). An flipped classroom teaching model: Effects on english language higher-order thinking skills, student engagement and satisfaction. Journal of Education and Practice, 7(9), 108–121.

Biocca, F. (1997). The Cyborg’s Dilemma: Progressive embodiment in virtual environments. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.1997.tb00070.x

Bowden, J. (2022). Analogues of engagement: Assessing tertiary student engagement in contemporary face-to-face and blended learning contexts. Higher Education Research & Development, 41(4), 997–1012.

Chakraborty, M., & Nafukho, F. (2014). Strengthening student engagement: What do students want in online courses? European Journal of Training and Development, 38(9), 782–802.

Chang, C., & Hsu, M. (2016). Understanding the determinants of users’ subjective well-being in social networking sites: An integration of social capital theory and social presence theory. Behaviour & Information Technology, 35(9), 720–729.

Chitkushev, L., Vodenska, I., & Zlateva, T. (2014). Digital learning impact factors: Student satisfaction and performance in online courses. International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 4(4), 356–359.

Conrad, C., Deng, Q., Caron, I., Shkurska, O., Skerrett, P., & Sundararajan, B. (2022). How student perceptions about online learning difficulty influenced their satisfaction during Canada’s Covid-19 response. British Journal of Educational Technology, 53(3), 534–557.

Dodwell, D. (2022). Time for a Covid-19 audit. South China Morning Post, Hong Kong. May 9, 2022, B3.

El-Sayad, G., Md Saad, N. H., & Thurasamy, R. (2021). How higher education students in Egypt perceived online learning engagement and satisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Computers in Education, 8(4), 527–550.

Fan, X., Jiang, X., & Deng, N. (2022). Immersive technology: A meta-analysis of augmented/virtual reality applications and their impact on tourism experience. Tourism Management, 91, 104534.

Finn, K., FitzPatrick, K., & Yan, Z. (2017). Integrating lecture and laboratory in health sciences courses improves student satisfaction and performance. Journal of College Science Teaching, 47(1), 66–75.

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109.

Garrison, D. R. (2007). Online community of inquiry review: Social, cognitive, and teaching presence issues. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 11(1), 61–72.

Gefen, D., & Straub, D. W. (2004). Consumer Trust in B2C e-Commerce and the importance of social presence: experiments in e-products and e-services. Omega, 32, 407–424.

Hair, F., Hult, G., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2022). A primer on partial least squares Structural Equation Modelling (3rd ed.). Sage.

Hair, F., Risher, J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24.

Kahn, P., Everington, L., & Kelm, K. (2017). Understanding student engagement in online learning environments: The role of reflexivity. Educational Technology Research and Development, 65, 203–218.

Karaoglan Yilmaz, F. G., & Yilmaz, R. (2022). Exploring the role of sociability, sense of community and course satisfaction on students’ engagement in flipped classroom supported by facebook groups. Journal of Computers in Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40692-022-00226-y

Karaoglan Yilmaz, F. G., & Yilmaz, R. (2022). Learning analytics intervention improves students’ engagement in online learning. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 27, 449–460.

Karaoglan Yilmaz, F. G., Zhang, K., Ustun, A., & Yilmaz, R. (2022). Transactional distance perceptions, student engagement, and course satisfaction in flipped learning: a correlational study. Interactive Learning Environment. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2022.2091603

Kuo, Y., Walker, A., Schroder, K., & Belland, B. (2014). Interaction, Internet self-efficacy and self-regulated learning as predictors of student satisfaction in online education courses. Internet and Higher Education, 20, 35–50.

Leong, P. (2011). Role of social presence and cognitive absorption in online learning environments. Distance Education, 32(1), 5–28.

Marques, R., Malafaia, C., Faria, J., & Menezes, I. (2020). Using online tools in participatory research with adolescents to promote civic engagement and environmental mobilization: The WaterCircle (WC) project. Environmental Education Research, 26(7), 1043–1059.

Miranda, S., & Saunders, C. (2003). The social construction of meaning: An alternative perspective on information sharing. Information Systems Research, 14(1), 87–106.

Ng, P. M., Chan, J. K., & Lit, K. K. (2022). Student learning performance in online collaborative learning. Education and Information Technologies, 27(6), 8129–8145.

Ooi, K. B., Hew, J. J., & Lee, V. H. (2018). Could the mobile and social perspectives of mobile social learning platforms motivate learners to learn continuously? Computers & Education, 120, 127–145.

Orlowski, M., Mejia, C., Back, R., & Fridrich, J. (2021). Transition to online culinary and beverage labs: Determining student engagement and satisfaction during COVID-19. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Education, 33(3), 163–175.

Osei-Frimpong, K., & McLean, G. (2018). Examining online social brand engagement: A social presence theory perspective. Technology Forecasting & Social Change, 128, 10–21.

Salas-Pilco, S. Z., Yang, Y., & Zhang, Z. (2022). Student engagement in online learning in Latin American higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. British Journal of Educational Technology, 53(3), 593–619.

TheVibes (February 2022) Leave decision on reopening campuses to unis, colleges: academics tell govt. Accessed on 15 Jun 2022, from https://www.thevibes.com/articles/education/54287/leave-decisions-on-reopening-of-campus-to-universities-colleges-academics-tell-govt

Quin, D. (2017). Longitudinal and contextual associations between teacher-student relationship and student engagement: A systematic review. Review of Educational Research, 87(2), 345–387.

Pavlou, P. A., Liang, H., & Xue, Y. (2007). Understanding and mitigating uncertainty in online exchange relationships: A principle-agent perspective. MIS Quarterly, 31, 105–136.

Rodriguez-Ardura, I., & Meseguer-Artola, A. (2020). Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 15(2), 1–5.

Shen, K. N., & Khalifa, K. (2008). Exploring multidimensional conceptualization of social presence in the context of online communities. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 24(2), 722–748.

Shen, K. N., Yu, A. Y., & Khalifa, K. (2010). Knowledge contribution in virtual communities: Accounting for multiple dimensions of social presence through social identity. Behaviour & Information Technology, 29(4), 337–348.

Shmueli, G., Sarstedt, M., Hair, J. F., Cheah, J. H., Ting, H., Vaithilingam, S., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: guidelines for using PLSpredict. European journal of marketing. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-02-2019-0189

Su, C. Y., & Guo, Y. (2021). Factors impacting university students’ online learning experiences during the COVID-19 epidemic. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 37(6), 1578–1590.

Sun, J. C. Y., & Rueda, R. (2012). Situational interest, computer self-efficacy and self-regulation: Their impact on student engagement in distance education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(2), 191–204.

Ustun, A., Karaoglan Yilmaz, F. G., & Yilmaz, R. (2021). Investigating the role of accepting learning management system on students’ engagement and sense of community in blended learning. Education and Information Technologies, 26, 4751–4769.

Wut, T. M., & Lee, S. W. (2021). Factors affecting students’ online behavioral intention in using discussion forum. Interactive Technology and Smart Education, 19(3), 300.

Wut, T. M., Lee, S. W., & Xu, J. (2022a). Work from home challenges of the pandemic era in Hong Kong: A stimulus-organism-response perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19, 3420.

Wut, T. M., Wong, H. S., & Sum, C. (2022). A Study of Continuance use intention of an online learning system after Coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic outbreak. Asia Pacific Journal of Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2022.2051696

Wut, T. M., & Xu, J. (2021). Person-to-person interactions in online classroom settings under the impact of COVID-19: a social presence theory perspective. Asia Pacific Education Review. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-021-09673-1

Yu, A., Tian, S., Vogel, D., & Kwok, R. (2010). Can learning be virtually boosted? An investigation of online social networking impacts? Computer & Education, 55(4), 1494–1503.

Funding

This work described in this paper was fully supported by a Grant from College of Professional and Continuing Education, Hong Kong Special Administration Region, China (BHM-TF-2021–002(J)).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the research committee of College of Professional and Continuing Education.

Informed consent

It was obtained from all subjects invovled in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Wut, T.M., Ng, P.Ml. & Low, M.P. Engaging university students in online learning: a regional comparative study from the perspective of social presence theory. J. Comput. Educ. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40692-023-00278-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40692-023-00278-8