Abstract

This review critically assessed the existence of presbygeusia, i.e., the impairment in taste perception occurring in the elderly, as a natural part of the aging process and its potential clinical implications. Several factors might contribute to age-related taste alterations (TAs), including structural changes in taste buds, alterations in saliva composition, central nervous system changes, and oral microbiota dysbiosis. A comprehensive literature review was conducted to disentangle the effects of age from those of the several age-related diseases or conditions promoting TAs. Most of the included studies reported TAs in healthy elderly people, suggesting that presbygeusia is a relatively frequent condition associated with age-related changes in the absence of pathological conditions. However, the impact of TAs on dietary preferences and food choices among the elderly seems to be less relevant when compared to other factors, such as cultural, psychological, and social influences. In conclusion, presbygeusia exists even in the absence of comorbidities or drug side effects, but its impact on dietary choices in the elderly is likely modest.

Highlights

Taste alterations (TAs) – defined as abnormalities or changes in the sense of taste involving a modification in the perception of flavours, which can result in a diminished, altered, or distorted sense of taste – are common in older people.

TAs are probably a natural part of the aging process, so that the term presbygeusia may justifiably be used for defining abnormal taste perception of the elderly, in the absence of well recognized pathological or pharmacological conditions.

The clinical implications of TAs on health status and dietary choices of the elderly are likely modest, as many other factors have been reported to be ultimately more relevant in influencing food intake of old people.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The term “presbygeusia” refers to the impairment of taste occurring in the elderly. Aging is a natural process affecting the entire body, resulting in a gradual decline in both physical and cognitive function [1]. The extent and rate of decline is highly variable among individuals, and include cognitive abilities, physical strength, cardiometabolic health, immune function, hormonal changes, and sensory functions [2]. Several sensory functions are affected by aging: vision (presbyopia), hearing (presbycusis), olfaction (presbyosmia) and taste.

Many age-related conditions might lead to impaired taste perception, such as changes in taste buds, decreased saliva production, alterations in the involved sensory nerves [3]. Although these changes occur physiologically during the aging process, impaired taste perception is not universally recognized as a natural phenomenon of aging, but rather as a pathological consequence of age-related chronic diseases (i.e., inflammation/infections in the oro/nasopharynx, post-traumatic or post-operative nerve damage, metabolic, endocrinological, neurologic and psychiatric diseases, malignancies, vitamin and mineral deficiencies, SARS-CoV-2 infection and burning mouth syndrome), environmental and chemical exposure, smoking habits, poor oral health, and polytherapy [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. .

The main objective of the present narrative review was assessing the existence of presbygeusia as a distinct entity in the healthy elderly by an extensive literature search. Secondarily, the potential clinical implications of TAs in the elderly were discussed.

Materials and methods

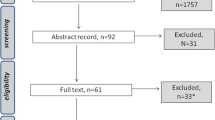

Studies investigating taste alterations in older adults (i.e., aged 65 years or older) without evident underlying pathological causes compared to healthy younger subjects were considered eligible for the present review. PubMed (National Library of Medicine), the Cochrane Library, Excerpta Medica dataBASE (EMBASE) and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) were queried until 30 May 2023. The search strategy employed a combination of database-specific subject headings and keywords including (‘taste alteration*’ OR ‘taste dysfunction*’ OR ‘taste problem*’) AND (aging OR age-related OR elderly). No restrictions were applied during the search. Reviews, case reports, case series and conference proceedings as well as studies published in a language other than English and studies in animals were excluded but manually examined for additional relevant literature.

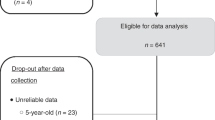

The identification of studies is summarized in Supplementary Fig. 1. The search strategy identified 837 studies; two investigators (SB and VP) independently screened titles and abstracts in duplicate for the selection of the included studies: 762 studies were excluded on title and abstract as clearly not relevant to the topic of the present paper. Then, the researchers independently assessed the full text of relevant studies and determined eligibility against the review topic. Only articles that explicitly assessed healthy individuals were included in the review. Any disagreement between the researchers in the study selection process was resolved through consensus or, if necessary, consultation with a third author (EF). A total of 15 observational studies were finally included in the review. The risk of bias was independently assessed for each included study by two authors (SB, VP) using the ROBINS-I (Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Intervention) tool for observational studies [16].

Findings from the included studies were summarized in section “Do taste alterations exist in healthy elderly?”. All relevant studies, even those not meeting the eligibility criteria for the main objective of the review, were consulted to write background sections and discuss clinical implications.

Definition of taste alterations

Taste alterations (TAs) refer to abnormalities or changes in the sense of taste involving a modification in the perception of flavours, which can result in a diminished, altered, or distorted sense of taste. Both quantitative and qualitative disorders of taste may be present [5]:

-

Quantitative abnormalities.

Hypogeusia: diminished taste perception of one or more specific tastants (sweet, sour, salty, bitter, umami).

Ageusia: absent taste function.

Hypergeusia: increased sensitivity to taste stimuli.

-

Qualitative abnormalities.

Dysgeusia: Altered perception of taste in response to a tastant stimulus.

Phantogeusia: perception of taste without a stimulus.

Aliageusia: taste disturbance in which a typically pleasant-tasting food or drink tastes unpleasant.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of TAs widely varies with the population studied and the underlying cause. Moreover, it is strongly influenced by the diagnostic tool employed, i.e., subjective assessments (self-reported questionnaires or scales), taste testing (whole-mouth tests with solutions or spray or regional tests with taste strips) or electrogustometry [5].

Overall, these disturbances are relatively common, with percentages ranging from 5 to 20% in the general population, being complete ageusia relatively rare (< 3%) and men more frequently affected than women [5, 6, 17,18,19,20,21,22]. TAs are more commonly reported in older adults [17, 19, 23,24,25,26] with a prevalence between 10% and 30% [13, 27, 28]. Sour and bitter are the most compromised tastes in the elderly, while the perception of sweet is maintained [13, 24, 25, 28, 29]. A small study reported regional differences in taste perception in elderly adults, being the most affected areas both the tip and mid-lateral regions of the tongue (but not the posteromedial) [30]; conversely, another research found an increased age-related decline in taste function on the posterior tongue surface, especially for sweet and bitter tastes [31]. Overall, the right side of the tongue showed lower thresholds of taste perception than the left side [26]. These findings arise a further problem in the interpretation of the available literature, since regional tests might be unable to correctly detect TAs, depending on the site of application.

Additionally, individuals reporting TAs showed an associated impairment in the sense of olfaction, while an isolated loss of taste was described in less than 10% of patients requiring assistance for an impairment in flavour perception [4, 6]. Since the perception of a flavour is a complex sensorial experience, involving not only taste, but also tactile and chemical sensations, smell, and temperature perception [32], olfactory and tactile stimulations may be actually confused with taste, owing to the complexity in the peripheral and central regulation of the chemosensory inputs, which are combined into a unified flavour perception [6, 33].

Pathophysiology

In addition to pathological causes and chronic diseases (which were not covered since they were beyond the purpose of the current review), several paraphysiological mechanisms have been proposed to explain the decreased taste sensitivity in older adults (Table 1).

Structural changes have been reported with aging, such as a reduced number of taste buds, a lower epithelial density of taste buds, and fewer taste cells per taste bud [34]. Fungiform papillae (FP) on the anterior part of the tongue are the most studied papillae because of the accessible position and the association of their density with taste bud density and the perception of gustatory stimuli [26, 35, 36]. Several studies consistently demonstrated an age-associated decline in density of FP [26, 37, 38]. Furthermore, the function of FP may be impaired, since a reduced vascular density has been reported together with an altered vascular morphology at the tip of the tongue in subjects over 60 years old when compared with younger individuals [26]. Both impairment in taste bud homeostasis, i.e., abnormal cell renewal, differentiation, regeneration of damaged cells, and cell membrane modifications with dysfunction of taste receptors due to aging processes and the cumulative damage caused by harmful environmental conditions throughout life, might contribute to TAs [34].

Changes in the flow and composition of saliva, with impaired transport and release of food molecules to the taste buds have been reported in the elderly [39]. Reduced levels and glycosylation of salivary mucin together with a reduced binding capacity to oral epithelial cells were found in saliva of older adults with impairments in both saliva viscoelasticity and the activation of bitter taste receptors with respect to younger adults [40].

Brain electrical neuroimaging by means of scalp-recorded electroencephalography revealed specific alterations in brain areas implicated in the taste processes in healthy elderly people with respect to younger counterparts, suggesting the involvement of the central nervous system in aging-related TAs [41].

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) activation during hedonic evaluation of sweet (sucrose) and bitter (caffeine) tastes were compared in 20 young (age 19–26 years) and 12 middle-aged (age 45–54 years) adults [42]. A greater bilateral activation in sensory (insula) and reward (lentiform nucleus) regions during evaluation of the sweet taste (but not bitter) was found in the younger group, thus suggesting that the early age-related decline in central processing of tastes may precede gustatory impairments of the elderly [42].

The inability to fully chew food [12], as well as the coverage of the palate with a dental prosthesis [43], might also be implicated in age-associated TAs.

Alterations in olfactory functions of the elderly, such as drying of the olfactory mucosa, damage to the olfactory epithelium due to environmental factors, abnormal turnover with reduction in the number of olfactory receptor cells, and the related abnormal retro-nasal stimulation of the olfactory receptors during deglutition might have an additional role in the impairment in taste perception [44].

Finally, impairment in the oral microbioma, which has been described in the older persons [45], has been increasingly recognized as a relevant factor in the mechanisms of altered taste perception by means of several mechanisms, such as the physical barrier exerted by surface tongue film of oral bacteria limiting access of tastants to taste receptors, the taste modulation by the bacterial metabolites, and the interaction of microbiota with extra-oral receptors [46].

Do taste alterations exist in healthy elderly?

The purpose of our review was to investigate the current knowledge about the existence of presbygeusia as a distinct entity in the healthy elderly. A few studies explicitly assessed healthy individuals without comorbidities, conditions or drug therapies impacting on taste perception; in particular, drug use was often not considered among exclusion criteria. In 15 observational studies the most attention was paid to ruling out potentially interfering conditions with the sense of taste and were finally included in the review. Overall, the risk of bias was considered moderate for all included studies (Supplementary Table 1); a serious risk of bias was identified in three studies mainly due to the potential selection bias and the lack of control for confounding factors [5, 19, 31].

The main characteristics of included articles were outlined in Table 2, specifying the types of stimuli and the methods of taste assessment adopted. Twelve studies reported TAs in the healthy elderly people [5, 17, 19, 23, 26, 47,48,49,50,51,52,53], whereas three articles presented more controversial data [31, 43, 54].

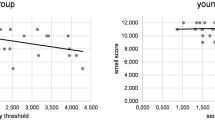

In a small cohort of institutionalized older patients, selected by the nursing staff for their healthy medical status, the taste detection thresholds for amino acids [50], sweeteners [51], and bitter compounds dissolved in water [52] were reported to be higher than in younger subjects. Similar findings were observed with different methods of taste assessment [5, 19, 23], even if more controversial results were reported for saltiness [54] and sweetness [43]. In another small group of community-dwelling healthy non-smokers subjects, Mojet et al. found an age-related decline in the perception of intensity of all tastants dissolved in water, but only for the salty and sweet tastants in product [47]; when participants wore a nose clip to reduce the potential influence of the odour, an age-related decline in taste perception was found for salty tastants only [48]. However, in a different cohort the ability to identify sweet and salty qualities was reported to not be affected by age [34].

Furthermore, Nakazato et al. reported the increase of electrogustometry thresholds in older subjects at the chorda tympani and glossopharyngeal nerve areas from the age of 60 years, and at the greater petrosal nerve area after 70 years old [17]. Similar findings were reported by Pavlidis et al., with gustatory thresholds correlated with FP density, shape, and vascularization in older participants [26].

In summary, despite their inherent limitations, current evidence seems to lead towards the existence of presbygeusia as a relatively frequent condition related to the physiological decline of the body’s functions occurring with age.

Clinical implications

TAs are unpleasant and disturbing conditions which may impact older people’s well-being by lowering their overall quality of life, decreasing their enjoyment of food, and impairing their ability to socialize when dining [6, 55]. Aging seems to result in a decline in taste function with tastant-dependent and not homogenous trend [29]. Physiological age-related decrease in gustatory function has been reported to be a slow and gradual process leading to a reduced awareness of TAs in individuals [13].

Age-related declines in taste may result in both a preference and consumption of stronger tasting products, as well as a loss of appetite, reduced food intake and undernutrition [3, 7]. However, the link between taste alterations, food preferences, and ultimately, food choices has not been proven, as neither preferences nor choices seem to be significantly influenced by TAs. Studies have indicated that older individuals, although experiencing some decline in sensory capabilities, exhibit a notable consistency in their food preferences, showing no preference for taste-enhanced food [54, 56]. A great variability of reported food preferences among the elderly with TAs has been reported, without clear-cut conclusions [57]. Food preferences may be more closely tied to culture or dietary customs rather than solely to sensory functions [58]. Moreover, the connections between food choices and intake with taste abnormalities were controversial, with many studies failing to establish a direct causal link [54, 59, 60]. Variations in taste receptor genes may result in different perceptions of taste and influence taste preferences. However, genetic predispositions only account for 20% of the variation in food preferences, with environmental factors playing a larger role [61]. Food preferences and choices are governed by a myriad of intricate processes, with sensory aspects (e.g., colour, smell, temperature, tactile and chemical sensations, in addition to taste) being involved alongside several other variables, such as mood, environment, health, allergies, convenience, hunger levels, cost, habits, cultural influences, social aspects, living conditions, attitudes towards food, religious beliefs, and life experiences [62]. Among the socio-cultural factors, income, education, country of origin, and knowledge of dietary/cooking skills were identified as the most significant influences of food choices in the elderly [63]. Other variables included biological, psychological, and situational factors (e.g., living alone, loss of a partner), as well as product characteristics (e.g., health claim, texture, price, portion size, promotions) [63]. Another systematic review highlighted influences from the past (e.g., childhood experiences and memories) and concerns about the future (e.g., loss of independence, fear of disability) as major drivers of food choices among the elderly [64].

Limitations

The importance of measuring the intensities of tastants dissolved in water has been reported to have limited relevance for the actual perception of taste in complex food products in “real-life” situations [48]. Few studies have conducted repeated measurements of taste thresholds, which likely provide more reliable measures of actual sensitivity, revealing greater individual variability among the elderly [65]. However, several studies had methodological limitations and small sample sizes [25]. There has been a wide range of ages studied across different research, and older individuals have been found to be relatively inaccurate in self-reporting taste dysfunction [66]. The degree to which published results may be compared and generalized is uncertain, as considered studies have used various methods of taste assessment, different food systems, diverse procedures to collect responsiveness data (e.g., threshold or suprathreshold stimuli), and varying definition of abnormalities, both for detection thresholds (the minimum concentration at which participants can reliably discriminate the taste from water) and recognition thresholds (the minimum concentration at which participants can identify the taste quality) [67]. Finally, it is important to acknowledge the possibility of publication bias, where research with null findings is less likely to be published, potentially leading to an overestimation of the prevalence of TAs in the elderly.

Conclusions

Our narrative review of the literature aimed to disentangle the effects of age from those of several age-related diseases or conditions potentially affecting taste. TAs should be regarded as a natural part of the aging process rather than a distinct disease, such that the term “presbygeusia” may reasonably be used to define abnormal taste perception of the elderly, in the absence of pathological conditions. However, the clinical relevance of TAs in the dietary choices of the elderly is likely to be limited, as many other factors eventually play a larger role in determining food intake in older adults.

Data availability

All Authors had all access to the data in this work and approved the submission of the present manuscript. All material in this assignment is Authors’ own work and does not involve plagiarism.

References

Goldstein S (1971) The biology of aging. N Engl J Med 285:1120–1129. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM197111112852005

Khan SS, Singer BD, Vaughan DE (2017) Molecular and physiological manifestations and measurement of aging in humans. Aging Cell 16:624–633. https://doi.org/10.1111/acel.12601

Chia CW, Yeager SM, Egan JM (2023) Endocrinology of taste with aging. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 52:295–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecl.2022.10.002

Syed Q, Hendler KT, Koncilja K (2016) The impact of Aging and Medical Status on Dysgeusia. Am J Med 129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.02.003. :753.e1–6

Fark T, Hummel C, Hähner A et al (2013) Characteristics of taste disorders. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 270:1855–1860. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-012-2310-2

Deems DA, Doty RL, Settle RG et al (1991) Smell and taste disorders, a study of 750 patients from the University of Pennsylvania Smell and taste Center. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 117:519–528. https://doi.org/10.1001/archotol.1991.01870170065015

Schiffman SS (1997) Taste and smell losses in normal aging and disease. JAMA 278:1357–1362. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1997.03550160077042

Solemdal K, Sandvik L, Willumsen T, Mowe M (2014) Taste ability in hospitalised older people compared with healthy, age-matched controls. Gerodontology 31:42–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/ger.12001

Sulmont-Rossé C, Maître I, Amand M et al (2015) Evidence for different patterns of chemosensory alterations in the elderly population: impact of age versus dependency. Chem Senses 40:153–164. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bju112

De Carli L, Gambino R, Lubrano C et al (2018) Impaired taste sensation in type 2 diabetic patients without chronic complications: a case-control study. J Endocrinol Invest 41:765–772. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-017-0798-4

da Silva LA, Jaluul O, Teixeira MJ et al (2018) Quantitative sensory testing in elderly: longitudinal study. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 76:743–750. https://doi.org/10.1590/0004-282X20180129

Alia S, Aquilanti L, Pugnaloni S et al (2021) The influence of age and oral health on taste perception in older adults: a case-control study. Nutrients 13:4166. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13114166

Sødal ATT, Singh PB, Skudutyte-Rysstad R et al (2021) Smell, taste and trigeminal disorders in a 65-year-old population. BMC Geriatr 21:300. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02242-6

Pellegrini M, Merlo FD, Agnello E et al (2023) Dysgeusia in patients with breast Cancer treated with Chemotherapy-A narrative review. Nutrients 15:226. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15010226

Mortazavi H, Shafiei S, Sadr S, Safiaghdam H (2018) Drug-related Dysgeusia: a systematic review. Oral Health Prev Dent 16:499–507. https://doi.org/10.3290/j.ohpd.a41655

Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC et al (2016) ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 355:i4919. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i4919

Nakazato M, Endo S, Yoshimura I, Tomita H (2002) Influence of aging on electrogustometry thresholds. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 16–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016480260046382

Vennemann MM, Hummel T, Berger K (2008) The association between smoking and smell and taste impairment in the general population. J Neurol 255:1121–1126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-008-0807-9

**el J, Ostwald J, Pau HW et al (2010) Normative data for a solution-based taste test. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 267:1911–1917. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-010-1276-1

Welge-Lüssen A, Dörig P, Wolfensberger M et al (2011) A study about the frequency of taste disorders. J Neurol 258:386–392. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-010-5763-5

Bhattacharyya N, Kepnes LJ (2015) Contemporary assessment of the prevalence of smell and taste problems in adults. Laryngoscope 125:1102–1106. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.24999

Rawal S, Hoffman HJ, Bainbridge KE et al (2016) Prevalence and risk factors of self-reported smell and taste alterations: results from the 2011–2012 US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Chem Senses 41:69–76. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjv057

Fukunaga A, Uematsu H, Sugimoto K (2005) Influences of aging on taste perception and oral somatic sensation. J Gerontol Biol Sci Med Sci 60:109–113. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/60.1.109

Schumm LP, McClintock M, Williams S Assessment of sensory function in the National Social Life, Health, and, Project A et al (2009) J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 64 Suppl 1:i76-85. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbp048

Methven L, Allen VJ, Withers CA, Gosney MA (2012) Ageing and taste. Proc Nutr Soc 71:556–565. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665112000742

Pavlidis P, Gouveris H, Anogeianaki A et al (2013) Age-related changes in electrogustometry thresholds, tongue tip vascularization, density, and form of the fungiform papillae in humans. Chem Senses 38:35–43. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjs076

Hoffman HJ, Ishii EK, MacTurk RH (1998) Age-related changes in the prevalence of smell/taste problems among the United States adult population. Results of the 1994 disability supplement to the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). Ann N Y Acad Sci 855:716–722. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10650.x

Boesveldt S, Lindau ST, McClintock MK et al (2011) Gustatory and olfactory dysfunction in older adults: a national probability study. Rhinology 49:324–330. https://doi.org/10.4193/Rhino10.155

Yoshinaka M, Ikebe K, Uota M et al (2016) Age and sex differences in the taste sensitivity of young adult, young-old and old-old Japanese. Geriatr Gerontol Int 16:1281–1288. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.12638

Nordin S, Brämerson A, Bringlöv E et al (2007) Substance and tongue-region specific loss in basic taste-quality identification in elderly adults. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 264:285–289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-006-0169-9

Wang J-J, Liang K-L, Lin W-J et al (2020) Influence of age and sex on taste function of healthy subjects. PLoS ONE 15:e0227014. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227014

Prescott J (2012) Multimodal chemosensory interactions and perception of flavor. In: Murray MM, Wallace MT (eds) The neural bases of multisensory processes. CRC Press/Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton (FL)

Migneault-Bouchard C, Hsieh JW, Hugentobler M et al (2020) Chemosensory decrease in different forms of olfactory dysfunction. J Neurol 267:138–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-019-09564-x

Feng P, Huang L, Wang H (2014) Taste bud homeostasis in health, disease, and aging. Chem Senses 39:3–16. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjt059

Walliczek-Dworschak U, Schöps F, Feron G et al (2017) Differences in the density of Fungiform Papillae and Composition of Saliva in patients with taste disorders compared to healthy controls. Chem Senses 42:699–708. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjx054

Piochi M, Dinnella C, Prescott J, Monteleone E (2018) Associations between human fungiform papillae and responsiveness to oral stimuli: effects of individual variability, population characteristics, and methods for papillae quantification. Chem Senses 43:313–327. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjy015

Piochi M, Pierguidi L, Torri L et al (2019) Individual variation in fungiform papillae density with different sizes and relevant associations with responsiveness to oral stimuli. Food Qual Prefer 78:103729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2019.103729

Fischer ME, Cruickshanks KJ, Schubert CR et al (2013) Factors related to fungiform papillae density: the beaver dam offspring study. Chem Senses 38:669–677. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjt033

Mese H, Matsuo R (2007) Salivary secretion, taste and hyposalivation. J Oral Rehabil 34:711–723. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2842.2007.01794.x

Pushpass R-AG, Pellicciotta N, Kelly C et al (2019) Reduced salivary mucin binding and glycosylation in older adults influences taste in an in vitro cell model. Nutrients 11:2280. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11102280

Iannilli E, Broy F, Kunz S, Hummel T (2017) Age-related changes of gustatory function depend on alteration of neuronal circuits. J Neurosci Res 95:1927–1936. https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.24071

Green E, Jacobson A, Haase L, Murphy C (2013) Can age-related CNS taste differences be detected as early as middle age? Evidence from fMRI. Neuroscience 232:194–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.11.027

Wayler AH, Perlmuter LC, Cardello AV et al (1990) Effects of age and removable artificial dentition on taste. Spec Care Dentist 10:107–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-4505.1990.tb00771.x

Doty RL (2018) Age-related deficits in taste and smell. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 51:815–825. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otc.2018.03.014

Belibasakis GN (2018) Microbiological changes of the ageing oral cavity. Arch Oral Biol 96:230–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archoralbio.2018.10.001

Schamarek I, Anders L, Chakaroun RM et al (2023) The role of the oral microbiome in obesity and metabolic disease: potential systemic implications and effects on taste perception. Nutr J 22:28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-023-00856-7

Mojet J, Christ-Hazelhof E, Heidema J (2001) Taste perception with age: generic or specific losses in threshold sensitivity to the five basic tastes? Chem Senses 26:845–860. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/26.7.845

Mojet J, Heidema J, Christ-Hazelhof E (2003) Taste perception with age: generic or specific losses in supra-threshold intensities of five taste qualities? Chem Senses 28:397–413. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/28.5.397

Sato H, Wada H, Matsumoto H et al (2022) Differences in dynamic perception of salty taste intensity between young and older adults. Sci Rep 12:7558. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-11442-y

Schiffman SS, Hornack K, Reilly D (1979) Increased taste thresholds of amino acids with age. Am J Clin Nutr 32:1622–1627. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/32.8.1622

Schiffman SS, Lindley MG, Clark TB, Makino C (1981) Molecular mechanism of sweet taste: relationship of hydrogen bonding to taste sensitivity for both young and elderly. Neurobiol Aging 2:173–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-4580(81)90018-x

Schiffman SS, Gatlin LA, Frey AE et al (1994) Taste perception of bitter compounds in young and elderly persons: relation to lipophilicity of bitter compounds. Neurobiol Aging 15:743–750. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-4580(94)90057-4

Yamauchi Y, Endo S, Yoshimura I (2002) A new whole-mouth gustatory test procedure. II. Effects of aging, gender and smoking. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016480260046418

Drewnowski A, Henderson SA, Driscoll A, Rolls BJ (1996) Salt taste perceptions and preferences are unrelated to sodium consumption in healthy older adults. J Am Diet Assoc 96:471–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-8223(96)00131-9

Jeon S, Kim Y, Min S et al (2021) Taste sensitivity of Elderly people is Associated with Quality of life and inadequate dietary intake. Nutrients 13:1693. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13051693

Mojet J, Christ-Hazelhof E, Heidema J (2005) Taste perception with age: pleasantness and its relationships with threshold sensitivity and supra-threshold intensity of five taste qualities. Food Qual Prefer 16:413–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2004.08.001

Sergi G, Bano G, Pizzato S et al (2017) Taste loss in the elderly: possible implications for dietary habits. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 57:3684–3689. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2016.1160208

Zallen EM, Hooks LB, O’Brien K (1990) Salt taste preferences and perceptions of elderly and young adults. J Am Diet Assoc 90:947–950. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-8223(21)01668-0

Mattes RD, Cowart BJ, Schiavo MA et al (1990) Dietary evaluation of patients with smell and/or taste disorders. Am J Clin Nutr 51:233–240. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/51.2.233

Kremer S, Bult JHF, Mojet J, Kroeze JHA (2007) Food perception with age and its relationship to pleasantness. Chem Senses 32:591–602. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjm028

Feeney E, O’Brien S, Scannell A et al (2011) Genetic variation in taste perception: does it have a role in healthy eating? Proc Nutr Soc 70:135–143. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665110003976

Host A, McMahon A-T, Walton K, Charlton K (2016) Factors Influencing Food Choice for Independently Living Older People-A Systematic Literature Review. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr 35:67–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/21551197.2016.1168760

Caso G, Vecchio R (2022) Factors influencing independent older adults (un)healthy food choices: a systematic review and research agenda. Food Res Int 158:111476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2022.111476

Govindaraju T, Owen AJ, McCaffrey TA (2022) Past, present and future influences of diet among older adults - a sco** review. Ageing Res Rev 77:101600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2022.101600

Stevens JC, Cruz LA, Hoffman JM, Patterson MQ (1995) Taste sensitivity and aging: high incidence of decline revealed by repeated threshold measures. Chem Senses 20:451–459. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/20.4.451

Soter A, Kim J, Jackman A et al (2008) Accuracy of self-report in detecting taste dysfunction. Laryngoscope 118:611–617. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLG.0b013e318161e53a

Doty RL (2019) Epidemiology of smell and taste dysfunction. Handb Clin Neurol 164:3–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-63855-7.00001-0

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This research did not receive any funding from agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Torino within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.P. and S.B. contributed to the conception of the study, the development of the methodology and the investigation; V.P. and S.B. wrote the original draft; M.B., E.F., F.M., G.I., R.P., A.C., S.R. supervised the process and reviewed and edited the draft; all Authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

For the present type of study, no ethical approval is required.

Consent for publication

All data considered for this secondary research are already in the public domain. For the present type of study, no formal consent is required.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ponzo, V., Bo, M., Favaro, E. et al. Does presbygeusia really exist? An updated narrative review. Aging Clin Exp Res 36, 84 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-024-02739-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-024-02739-1