Abstract

Background

The intergenerational physical activity program aims to promote the health, social engagement, and well-being of older adults. It is essential to comprehend the barriers and facilitators that affect their involvement to develop successful intervention strategies. This systematic review critically examines available research to identify the factors that impact the participation of older adults in intergenerational physical activity programs.

Methods

This study retrieved 13 electronic databases (from January 2000 to March 2023) and used a social-ecological model to classify and analyze the identified facilitators and barriers.

Results

A total of 12 articles were included, which identified 73 facilitators and 37 barriers. These factors were condensed into 7 primary themes and 14 sub-themes in total.

Conclusions

The factors influencing the participation of older adults in intergenerational physical activities are multifaceted. These factors guide project developers, policymakers, and practitioners in develo** and implementing intergenerational physical activity programs to help address global aging issues and promote intergenerational connections.

Trial registry

PROSPERO ID: CRD42023420758.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the context of global aging, promoting physical activity (PA) [1] among older adults has become an urgent public health priority. The World Health Organization has developed specific guidelines for physical activity in older adults [1], recommending that older adults engage in at least 150 min of moderate to vigorous aerobic PA per week and maintain a variety of PA on 3 or more days per week. However, a report showed that approximately 28% of Americans aged 50 and above do not engage in any form of PA, apart from work and daily life, in the past month [2]. The lack of regular PA in older adults [3], which has various negative effects on their overall health and functioning [4, 5]. The absence of PA in older adults leads to a decrease in physical function, mobility [6] and independence [7], resulting in a decrease in quality of life [2] and an increase in healthcare expenses [8]. Therefore, it is important to explore more appealing and effective strategies to encourage older adults to stay physically active.

Intergenerational physical activities have emerged as a promising strategy for addressing the lack of PA among older adults [9]. These projects involve structured and unstructured physical activities [10] that bring together people of different ages and promote interaction, mutual learning, and social support [11, 12]. Intergenerational PA not only provides exercise opportunities for older adults [13], but also promotes intergenerational connections and reduces age-related stereotypes [14]. Intergenerational relationships have been identified as a source of motivation for older adults to engage in regular exercise [15]. Studies [16] have shown that intergenerational PA enhances older adults’ self-esteem, making them more likely to engage in PA. Wu's research has found that verbal or nonverbal interactions between older adults and younger students in intergenerational PA contribute to meaningful intergenerational relationships that enhance social connectedness and reduce social isolation [17].

Although the potential benefits of intergenerational PA, the needs and interests [18,19,20,21] of older adults who participate in such activities may be overlooked [18] and participation rates among older adults remain relatively low [19]. To effectively promote and implement such programs, it is crucial to understand the barriers that hinder adults' participation and the facilitators that encourage them to do so.

As far as we know, there is no systematic review of facilitators and barriers to intergenerational PA, and there is a particular lack of perspectives from older adults. Previous systematic reviews have identified barriers and facilitators to PA participation among older adults [20,21,22,23], and given the intergenerational context of the current review, where older adults participate in PA alongside children or young people, it is certain the barriers and facilitators to this intergenerational activity are different from other types of PA. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to identify the barriers, facilitating factors, and motivating factors associated with the participation of older adults in intergenerational PA. We will categorize these factors within the theoretical framework of the social–ecological model [24], which includes individual, interpersonal, community, and policy levels [25]. The model is often used to investigate potential factors related to PA in older adults and classify them [26,27,28]. This model not only takes into account the significance of psychological and social factors in engaging in PA and using PA programs but also considers the role played by organizational, environmental, and policy factors.

Methods

This review was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) and followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guideline [29].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were: (a) all types of empirical research designs (quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods research) to achieve multiple research objectives; (b) recruiting participants aged 50 and above; (c) PA is defined as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure [30]. In this review, intergenerational PA involves promoting health through physical activities and intergenerational learning, such as dancing, yoga, tai chi, etc., with older adults and children or youth together. (d) The main focus is on the barriers and facilitators for older adults to participate in intergenerational physical activities. Barriers refer to individual perceptual barriers to participating in intergenerational public activities, while facilitators refer to characteristics within individuals or their surroundings that motivate intergenerational public activities. (e) Complete papers published in English or Chinese.

The exclusion criteria included: (a) studies without original participant data on barriers and facilitators; (b) studies that are commentaries, editorials, communications, or conference abstracts; (c) elderly individuals with dementia (Alzheimer's disease or related disorders).

Search strategy

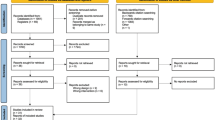

The database used: PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, SCOPUS, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PsycINFO, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, WANFANG, and Chinese Biomedical. The retrieval time starts from January 2000 to March 2023. The search strategies used are presented in Appendix A. In addition, the reference lists of targeted articles were manually screened for inclusion of eligible studies (Fig. 1).

Quality appraisal

The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) is used by two independent assessors to rigorously evaluate the quality of included studies [31]. The MMAT is applicable for assessing various types of research designs, including qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods studies. This assessment involves five specific questions for each study design to evaluate the quality of the included research. These questions address the purpose and design of the retrospective study, recruitment strategies, data collection, and analysis methods, presentation and discussion of research findings, and conclusions. To assess the quality of the studies included, we calculated the overall quality score, which is the lowest score of the components of the study. If the overall score of the study is > 4, it is considered "high quality", 3–4 is "moderate quality", and < 3 is "low quality". The final score is determined through discussion and negotiation with the third reviewer (WHY); see Appendix B.

Data extraction and synthesis

Two researchers (ZF & LLF) extracted data from selected full-text studies. Data were extracted on authors, country of publication, year of publication, participant characteristics (number, age), study site, methods, and primary outcomes, reported barriers, and facilitators. The most relevant and appropriate approach to data synthesis for this review was descriptive narrative synthesis. Because papers with both qualitative and quantitative designs were included, a meta-analysis of the data was deemed inappropriate. Discussions between the two writers (ZF & LLF) cleared any uncertainties or doubtful points. Another author (ZH) cross-checked 20% of the randomly selected data extraction records.

Two researchers (ZF & LLF) carried out the data synthesis. The data were extracted using the social–ecological model adaptation framework [24], which included four levels: individual, interpersonal, community, and policy, and the extracted facilitators and/or barriers to intergenerational PA were organized into descriptive major themes and sub-themes using an inductive approach. The (sub)themes were then classified based on the levels of the social–ecological model. Based on the included studies, the total intergenerational PA intervention was interpreted as a factor that might enhance older adults' continued participation in intergenerational PA due to the inability to distinguish which intervention factors were facilitators and/or hindrances.

The social–ecological model [24] is divided into four levels: (1) individual: characteristics such as personal attitudes, motivation, and self-efficacy; (2) interpersonal: family, friends, peers, and other social support systems, as well as ties to social and cultural practices; (3) community: the weather, environmental, and transportation factors that provide intergenerational PA programs, infrastructure, and resources; and (4) policy: government policies and community-based programs.

Results

Study selection

The results of the search, screening, and inclusion of studies are reported using the PRISMA flowchart, as shown in Fig. 1. The database search resulted in 2816 records. After removing duplicates, 1115 studies were screened according to title and abstract relevance, of which 904 did not meet the inclusion criteria. Then, the remaining 211 studies were considered potentially eligible and read in full, and another 199 were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria. Finally, 12 studies were included in the review, including one qualitative study, six quantitative studies, and five mixed-methods studies [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43].

Study characteristics

Table 1 shows the main characteristics of all 12 papers, all of which were published in English between 2006 and 2020 conducted in 6 countries/regions, the United States (n = 7), and one study each in Switzerland, Italy, Spain, Iran, and Canada. These studies provided information on the obstacles and facilitators to older adult groups' participation in intergenerational PA. Most studies used quantitative study methods (n = 5) [33,34,35,36, 38] and mixed-methods analysis (n = 5) [32, 39,40,41,42]. One study used a qualitative study method [37].

Quality assessment

The MMAT appraisal results are presented in Appendix B. The included studies had methodological quality scores ranging from zero to a maximum score of 5. All studies had a quality score of more than 3, and 3 of the 12 studies scored 5 [33, 36, 38]. The remaining studies scored 4 (n = 8) [32, 34, 35, 37, 39, 40, 42, 43] and 3 (n = 1) [41]. Generally, the articles that were included exhibited a level of quality ranging from moderate to high.

Barriers and facilitators

This study focused on different types of intergenerational PA activities, focusing on the barriers and facilitators to participation in these programs among the older population. A social-ecological model was used to report these barriers and facilitators (see Table 2), summarizing them at 4 levels, summarizing 7 main themes and 14 sub-themes, with 32 individual, 14 interpersonal, 23 community, and 4 policy-level (73 in total) facilitators and 20 individual, 4 interpersonal, 11 community, and 2 policy-level (37 in total) barriers, Further details are presented in Appendix C.

Individual level

In terms of older adults’ knowledge, awareness and attitude, positive attitudes, enjoyment or interest, and sense of achievement were common facilitators [32, 34, 35, 38, 40, 42], In addition, the need for activity, learning of skills, and perceived benefits of exercise are also facilitators [37, 40, 41]. In terms of personal and health factors, the groups of older women, married persons, housewives, and farmers show a higher interest in group activities, especially intergenerational physical activity [34, 35]. Older adults, particularly elderly women, housewives, and married individuals, have more leisure time and a more flexible schedule, which makes it easier for them to engage in intergenerational physical activities [35]. Engaging in physically challenging and stimulating intergenerational physical activities with children can bring about a sense of youthfulness, vitality, and happiness [32, 34, 40, 42], as well as enhance intelligence and strength and improve overall health [35, 36, 40, 42], which are facilitators of older adults' participation in intergenerational physical activity. For farmers, participation in intergenerational physical activity aligns with the communal spirit in rural areas [33, 44], making it a more attractive option for them [34]. However, these factors are not unique to the groups of older women, housewives, married persons, and farmers; they may be more pronounced in these groups because of their particular life circumstances and social dynamics. At the individual level, physical health conditions such as age differences, fear of fatigue, and physical limitations are considered barriers [32, 34, 35, 39]. Language barriers, lack of motivation, time, and interest discourage older adults from actively participating in activities [32, 37, 41]. Social roles, obligations, and low income, especially for older women who need to prioritize family care, limit their participation in intergenerational PA [39]. Non-compliance or disturbance in the activity and preference of exercise program are also barriers [39, 40].

Interpersonal level

Family members, partners, and friends can do PA together as facilitators for older adults to participate in activities [35, 39, 43]. Develo** or improving interpersonal relationships, facilitating communication, and motivating each other during the activity are also facilitators [32, 35, 37, 38, 40, 41]. Religious culture or values, such as familism, promote active participation of older adults in intergenerational exercise activities [32, 36]. Disharmonious family relationships [34] and lack of family support [32] were barriers to interpersonal relationships, as were barriers to communication between older adults and children in physical activities and leadership challenges in older adults [40].

Community level

Community-level facilitators include those in the built environment, such as those having enough space for exercise [39, 41], communities having a park, fitness center, or equipment [36, 39, 42]. Good weather [42], convenient and safe transportation facilities [36], as well as familiar and easily accessible site [42] help older adults reach sites for intergenerational physical activities. Program sustainability, consistency, such as continued, increased financial investment in the program [37, 40], coaches' fidelity behavior [39], and consistent play programs for older adults and children [40] are also important contributing factors. Certainly, low-difficulty and fun PA programs such as recreational walking [36], and lack of transportation [32, 37] are community-level barriers, such as in urban settings where it is more difficult for older adults to pick up their grandchildren and then go to other sites for activities [34]. Less knowledge/awareness of intergenerational PA programs [32] and barriers to continued older adult participation in intergenerational PA programs, such as technical difficulties associated with exercise games and exercise itself, and a lack of younger adult trainers [41, 42].

Policy/institutional level

The development, expansion, and management of activities are important facilitators of the continued participation of older adults [36, 40]. Also, the use of virtual remote technology has helped older adults continue to participate in activities when they are unable to gather in person during the COVID-19 pandemic [40]. In contrast, organizational issues [40] and the relatively short duration of the program [41] were the barriers.

Discussion

In this systematic review of 12 studies, the barriers and facilitators to intergenerational PA from the perspective of older adults were complex. This study combines these barriers and facilitators by comprehensively identifying them at four levels of the social–ecological model. In this model, factors related to individuals, interpersonal relationships, communities, and policies have become highly influential in the field of older adults in intergenerational PA. The study reveals that barriers are primarily focused on the personal and community levels, with some barriers also present at the interpersonal level. On the other hand, promoting factors are most commonly observed at the personal level, with relatively equal proportions of promoting factors at the interpersonal and community levels.

At the individual level, interest in exercise, enjoyment, and perceived benefits all have a significant impact on encouraging older adults to participate in intergenerational PA. Jenkin’s [45] study also supports this viewpoint, showing that the benefits older adults gain from participating in community PA increase their participation. The intergenerational nature of PA is intriguing and attracts older adults to participate in activities [33, 38]. In these activities, older adults and young people come together to enjoy the benefits of intergenerational exercise [34], leading to improvements in their physical and mental well-being [33]. This finding is similar to Lakicevic's [46] research, which suggests that novel PA measures can enhance participants' interest and enjoyment, motivating them to maintain PA and ultimately achieve better health outcomes. Bethancourt [47] and Franco's study also mentions that the physiological and psychological benefits of PA serve as promoting factors for engaging in PA.

Other personal-level facilitators were experienced when older people engaged in intergenerational PA, so various PA advantages regarding mental and physical wellness have been noted, such as increased self-confidence, accomplishment, well-being, and improved appearance [48], cognition [49], and strength [50]. Perceiving improvements in psychological well-being through enhanced emotions is correlated with the motivation for elderly individuals to engage in physical activities [51]. This viewpoint is also supported by findings in our study. Additionally, self-efficacy plays a crucial role in this process. Royse's research also suggests that exercise can enhance self-efficacy and increase PA, creating a positive cycle that promotes a positive lifestyle [52]. In Wu's research, encouraging the elderly to participate in choreography in intergenerational dance activities not only improves the self-efficacy and sense of accomplishment of the elderly but also improves their creativity and activity motivation [17].

The research emphasizes that the motivation of older adults is an important factor in promoting PA and intergenerational PA. To attract older adults to participate in intergenerational PA, it is necessary to consider older adults' motivation to participate and its significance, which is consistent with the previous studies [27, 51, 53].

The most commonly reported barriers are related to physical condition, discomfort (age and activity differences), and lack of motivation and time. Physical condition has been recognized as a common barrier for older adults participating in physical activities [54, 55], but the physical health of children in intergenerational PA can also affect older adults' ability to continue participating, for example, when grandchildren also experience injury-related health problems and older adults may have to discontinue their activities [56].

Older adults expect the design of intergenerational PA programs to be designed with their age and physical conditions [56]. To guarantee that intergenerational PA and sports programs are acceptable, program planners must first discover the types of PA that older adults are most comfortable participating in [57]. Barriers to older adults’ participation in intergenerational PA show how strongly age and gender-related interpersonal and cultural factors influence individual behavior, as has been found in previous research [58].

Several studies [59,60,61] have reported similar findings regarding the discomfort that older adults experience in intergenerational programs. These studies have found that older adults often face difficulties in communicating with younger people and encounter inherent ageism, an inability to fully integrate into activities. In the context of intergenerational PA, older adults often experience age-related discomfort due to concerns about fatigue and being unable to keep up with the younger participants [32, 34]. Differences in activity preferences between genders are observed in older adults. Older men tend to prefer physical activities that are more intense or involve competition and outdoor activities, which may lead to a greater inclination of women toward intergenerational activities, especially indoor sports. This conclusion is consistent with Varma's [62] research. However, Gobbi's [63] and Arazi’s [64] study mentioned that the participation rate of women in physical activities may be lower than that of men due to their fear of falling, which could be influenced by cultural and geographical factors. Women face more restrictions in this regard. Additionally, the lack of sufficient time for older adults to engage in intergenerational physical activities may be related to their family responsibilities and conflicting obligations.

Two studies [23, 65] have provided support for this point. The review found that minority groups, particularly women, need to take on more family responsibilities [32, 41].

At the interpersonal level, the support of family and friends is one of the most common facilitators [21, 66]. It is known that social support promotes PA in older adults, and studies have shown that the majority of older adults who participate in intergenerational programs need support and companionship [67]. In May [68] and Brown's [69] study, it was also recommended that family PA opportunities be provided and that families and friends participate in intergenerational PA together to support and encourage each other to keep them active. Similarly, in Jarrott's [70] study, it was proposed to include mechanisms to promote friendship and socialization, provide meaningful roles, and reduce isolation and loneliness in intergenerational sports programs [67].

Fortunately, establishing a good relationship with children can motivate older adults to continue exercising [32, 42], which aligns with Caroline's [71] research findings, positive intergenerational relationships are mutually beneficial, as children gain experience from older adults, while older adults experience a greater sense of self-worth from children. Additionally, both older adults and children exhibit similarities in physical inclinations, such as balance, strength performance [72], and mutual needs in social learning [73].

Furthermore, the participation of elderly individuals in intergenerational PA is closely related to cultural background and customs. Ethnic minorities, particularly elderly women, are more affected by this, while the cultural emphasis on family in Latino communities encourages intergenerational PA participation [32]. A descriptive review [74], also noted the low participation of ethnic minority older women in PA and the need to identify culturally safe community-based PA. Additionally, language is a factor that needs to be considered. Organizing intergenerational sports activities in the participants' primary language can enhance their sense of self-efficacy in participating in these activities.

At the community level, although the promotion factors for elderly participation in intergenerational physical activities outweigh the obstacles, potential barriers such as extreme weather conditions, difficult physical activities, inconvenient transportation, a lack of young coaches, incomplete infrastructure, and technical difficulties still exist. For many older adults, bad weather is a difficult obstacle to overcome and a factor that hinders their ability to participate in outdoor activities [70]. This finding is supported by several studies [75, 76], particularly for residents living in Midwestern cities in the United States [65].

Another barrier factor to participation in intergenerational PA is safety. Unfamiliar locations or a lack of direct transportation often lead to high attrition rates, especially for older adults who rely on walking or public transportation. This finding is supported by the research of Barnett [77] and Lin [78], who systematically examined and quantified the built environment correlates of PA in older adults. Hamer’s [79] study indicates that safety, accessible destinations, and convenient travel paths facilitate older adults' active participation in PA.

Exergaming is an innovative approach that amalgamates PA with video games, and it could offer a fresh experience for older adults, encouraging their interest in intergenerational PA. According to Anderson’s [80] research, older adults appreciated the challenge of playing against virtual trainers as well as the visual stimulus offered by games. This not only helps to focus attention on the enjoyment of electronic games but also gains the health benefits of PA. Phang's [81] study supports this finding by demonstrating that digital intergenerational programs can increase older adults' engagement and reduce loneliness.

However, technological difficulties such as device setup and connectivity pose a challenge for older adults who are unfamiliar with operating such devices. In Chao's study [82], older adults were provided with various levels of exercise games, and this personalized choice helped improve participants' exercise attendance. These issues necessitate consideration and resolution in future intergenerational PA projects' design.

Large scale and long duration are policy-level barriers, which are reflected in other social–ecological levels through high employee turnover. A systematic review [9] supports this finding, indicating that long or large-scale PA increases interference with the existing commitments or daily activities of older adults. Therefore, appropriately reducing the duration of activities may encourage support and interest among older adults. Strand [41] suggests starting with small-scale projects and gradually expanding them to ensure participation and commitment. Therefore, in the future, when formulating intergenerational PA, considering appropriate compression of activity duration may encourage the support and interest of older adults.

Limitations and prospects

Although this study has made every effort to ensure the rigor of the mixed-methods systematic review and has used the theoretical framework of the social–ecological model to capture barriers and facilitators, there are still some limitations. First, most of the studies included in this systematic review were conducted in high-income countries, thereby omitting crucial factors that may impact middle-income and low-income nations. Furthermore, in our review, the elderly population with cognitive impairments was excluded. However, many of them could benefit from intergenerational programs [11]. Additionally, while a meta-analysis would be ideal, it is not practical owing to the lack of consistency among articles, as well as the disparities in outcomes and samples. Finally, it was observed that, while intergenerational projects are growing in popularity, there is an absence of academic research on specific projects, and most of the research is descriptive and lacks clear results, indicating that further exploration is needed in the field of intergenerational studies.

Conclusion

In summary, the goal of this research is to better comprehend the barriers and facilitators that older adults face in participating in intergenerational PA from their perspective. Furthermore, this study identifies these barriers and facilitators across multiple levels, which span the interpersonal, policy organizational, and individual levels, providing a crucial reference for future policymakers, researchers, and professionals to create and improve intergenerational PA for this demographic. However, it is worth noting that there is a lack of similar research from middle- and low-income countries, so future studies should consider perspectives from these countries. We suggest that future research should investigate the sustainability and scalability of intergenerational PA and examine specific impacts on different subgroups of older adults, thus having a positive impact on promoting physical, mental, and cognitive health, preventing falls, and modeling behaviors in older adults.

Availability of data and materials

All the data used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S et al (2020) World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med 54:1451–1462. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955

(2022) Adults need more physical activity. In: Cent. dis. control prev. https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/inactivity-among-adults-50plus/index.html. Accessed 28 June 2023

Watson KB, Carlson SA, Gunn JP et al (2016) Physical inactivity among adults aged 50 years and older—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 65:954–958. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6536a3

New Eurobarometer on sport and physical activity. In: Eur. Comm.—Eur. Comm. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_5573. Accessed 1 July 2023

Carlson SA, Adams EK, Yang Z et al (2018) Percentage of deaths associated with inadequate physical activity in the United States. Prev Chronic Dis 15:E38. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd18.170354

Thomas E, Battaglia G, Patti A et al (2019) Physical activity programs for balance and fall prevention in elderly. Medicine (Baltimore) 98:e16218. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000016218

Cunningham C, O’Sullivan R, Caserotti P et al (2020) Consequences of physical inactivity in older adults: a systematic review of reviews and meta-analyses. Scand J Med Sci Sports 30:816–827. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.13616

Ding D, Lawson KD, Kolbe-Alexander TL et al (2016) The economic burden of physical inactivity: a global analysis of major non-communicable diseases. Lancet 388:1311–1324. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30383-X

Directorate-General for Education Y, ECORYS (2020) Map** study on the intergenerational dimension of sport: final report to the European Commission. Publications Office of the European Union, LU

Iliano E, Beeckman M, Latomme J et al (2022) The GRANDPACT project: the development and evaluation of an intergenerational program for grandchildren and their grandparents to stimulate physical activity and cognitive function using co-creation. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19:7150. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127150

Sharifi S, Babaei Khorzoughi K, Khaledi-Paveh B et al (2023) Association of intergenerational relationship and supports with cognitive performance in older adults: a systematic review. Geriatr Nur (Lond) 52:146–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2023.05.014

Jaworski M (2011) Reminiscences of things past: innovative intergenerational project builds skills and supports elders. Geriatr Nur (Lond) 32:148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2011.01.010

Tan EJ, Xue Q-L, Li T et al (2006) Volunteering: a physical activity intervention for older adults—the experience Corps® program in Baltimore. J Urban Health 83:954–969. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-006-9060-7

Krzeczkowska A, Spalding D, Mcgeown W et al (2021) A systematic review of the impacts of intergenerational engagement on older adults’ cognitive, social, and health outcomes. Ageing Res Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2021.101400

Santini S, Tombolesi V, Baschiera B et al (2018) Intergenerational programs involving adolescents, institutionalized elderly, and older volunteers: results from a pilot research-action in Italy. BioMed Res Int 2018:4360305. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/4360305

Martins T, Midão L, Martínez Veiga S et al (2019) Intergenerational programs review: study design and characteristics of intervention, outcomes, and effectiveness. J Intergener Relatsh 17:93–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/15350770.2018.1500333

Wu VX, Yap XY, Tam WSW et al (2023) Qualitative inquiry of a community dance program for older adults in Singapore. Nurs Health Sci 25:341–353. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.13032

Cohen-Mansfield J, Jensen B (2017) Intergenerational programs in schools: prevalence and perceptions of impact. J Appl Gerontol 36:254–276. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464815570663

A senior-centered model of intergenerational programming with young children—Mary Dellmann-Jenkins, 1997. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/073346489701600407. Accessed 10 June 2023

Baert V, Gorus E, Mets T et al (2011) Motivators and barriers for physical activity in the oldest old: a systematic review. Ageing Res Rev 10:464–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2011.04.001

Franco MR, Tong A, Howard K et al (2015) Older people’s perspectives on participation in physical activity: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative literature. Br J Sports Med 49:1268–1276. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2014-094015

Jenkin CR, Eime RM, Westerbeek H et al (2017) Sport and ageing: a systematic review of the determinants and trends of participation in sport for older adults. BMC Public Health 17:976. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4970-8

Spiteri K, Broom D, Bekhet AH et al (2019) Barriers and motivators of physical activity participation in middle-aged and older adults—a systematic review. J Aging Phys Act 27:929–944. https://doi.org/10.1123/japa.2018-0343

McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A et al (1988) An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q 15:351–377. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019818801500401

Sallis JF, Cervero RB, Ascher W et al (2006) An ecological approach to creating active living communities. Annu Rev Public Health 27:297–322. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102100

Baert V, Gorus E, Guldemont N et al (2015) Physiotherapists’ perceived motivators and barriers for organizing physical activity for older long-term care facility residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc 16:371–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2014.12.010

Baert V, Gorus E, Calleeuw K et al (2016) An administrator’s perspective on the organization of physical activity for older adults in long-term care facilities. J Am Med Dir Assoc 17:75–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2015.08.011

Boulton ER, Horne M, Todd C (2018) Multiple influences on participating in physical activity in older age: develo** a social ecological approach. Health Expect 21:239–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12608

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M et al (2015) Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 4:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

Global action plan on physical activity 2018–2030: more active people for a healthier world. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/272722. Accessed 10 June 2023

Hong QN, Pluye P, Fàbregues S et al (2019) Improving the content validity of the mixed methods appraisal tool: a modified e-Delphi study. J Clin Epidemiol 111:49-59.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.03.008

Ramos AK, Dinkel D, Trinidad N et al (2023) Acceptability of intergenerational physical activity programming: a mixed methods study of Latino aging adults in Nebraska. J Aging Health. https://doi.org/10.1177/08982643231166167

Minghetti A, Donath L, Zahner L et al (2021) Beneficial effects of an intergenerational exercise intervention on health-related physical and psychosocial outcomes in Swiss preschool children and residential seniors: a clinical trial. PeerJ 9:e11292. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.11292

Buonsenso A, Fiorilli G, Mosca C et al (2021) Exploring the enjoyment of the intergenerational physical activity. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol 6:51. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk6020051

Canedo-García A, García-Sánchez J-N, Díaz-Prieto C et al (2021) Evaluation of the benefits, satisfaction, and limitations of intergenerational face-to-face activities: a general population survey in Spain. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18:9683. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189683

Zhong S, Lee C, Lee H (2020) Community environments that promote intergenerational interactions vs. walking among older adults. Front Public Health 8:587363. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.587363

Atkins R, Deatrick JA, Gage GS et al (2019) Partnerships to evaluate the social impact of dance for health: a qualitative inquiry. J Community Health Nurs 36:124–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370016.2019.1630963

Ebrahimi Z, Ghandehary E, Veisi K (2019) Comparing the effect of yoga exercise and intergenerational interaction program on elderlies’ mental health. J Res Health. https://doi.org/10.29252/jrh.9.5.401

Young T, Sharpe C (2016) Process evaluation results from an intergenerational physical activity intervention for grandparents raising grandchildren. J Phys Act Health 13:525–533. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2015-0345

McConnell J, Naylor P-J (2016) Feasibility of an intergenerational-physical-activity leadership intervention. J Intergener Relatsh 14:220–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/15350770.2016.1195247

Strand KA, Francis SL, Margrett JA et al (2014) Community-based exergaming program increases physical activity and perceived wellness in older adults. J Aging Phys Act 22:364–371. https://doi.org/10.1123/japa.2012-0302

Perry CK, Weatherby K (2011) Feasibility of an Intergenerational Tai Chi program: a community-based participatory research project. J Intergener Relatsh 9:69–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/15350770.2011.544215

Ransdell LB, Robertson L, Ornes L et al (2005) Generations exercising together to improve fitness (GET FIT): a pilot study designed to increase physical activity and improve health-related fitness in three generations of women. Women Health 40:77–94. https://doi.org/10.1300/J013v40n03_06

Fien S, Linton C, Mitchell JS et al (2022) Characteristics of community-based exercise programs for community-dwelling older adults in rural/regional areas: a sco** review. Aging Clin Exp Res 34:1511–1528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-022-02079-y

Jenkin CR, Eime RM, Westerbeek H et al (2018) Sport for adults aged 50+ years: participation benefits and barriers. J Aging Phys Act 26:363–371. https://doi.org/10.1123/japa.2017-0092

Lakicevic N, Gentile A, Mehrabi S et al (2020) Make fitness fun: could novelty be the key determinant for physical activity adherence? Front Psychol 11:577522. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.577522

Bethancourt HJ, Rosenberg DE, Beatty T et al (2014) Barriers to and facilitators of physical activity program use among older adults. Clin Med Res 12:10–20. https://doi.org/10.3121/cmr.2013.1171

Leong KS, Klainin-Yobas P, Fong SD et al (2022) Older adults’ perspective of intergenerational programme at senior day care centre in Singapore: a descriptive qualitative study. Health Soc Care Community 30:e222–e233. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13432

Yasunaga M, Murayama Y, Takahashi T et al (2016) Multiple impacts of an intergenerational program in Japan: evidence from the research on productivity through intergenerational sympathy project. Geriatr Gerontol Int 16:98–109. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.12770

Dsouza JM, Chakraborty A, Kamath N (2023) Intergenerational communication and elderly well-being. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cegh.2023.101251

Use it or lose it: a qualitative study of the maintenance of physical activity in older adults | BMC Geriatrics | Full Text. https://bmcgeriatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12877-019-1366-x. Accessed 29 June 2023

Royse LA, Baker BS, Warne-Griggs MD et al (2023) “It’s not time for us to sit down yet”: how group exercise programs can motivate physical activity and overcome barriers in inactive older adults. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being 18:2216034. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2023.2216034

Kenning G, Ee N, Xu Y et al (2021) Intergenerational practice in the community—what does the community think? Soc Sci 10:374. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10100374

Bauman AE, Reis RS, Sallis JF et al (2012) Correlates of physical activity: why are some people physically active and others not? Lancet 380:258–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60735-1

Are the recommended physical activity guidelines practical and realistic for older people with complex medical issues?—PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33347040/. Accessed 12 June 2023

Salari SM (2002) Intergenerational partnerships in adult day centers: importance of age-appropriate environments and behaviors. Gerontologist 42:321–333. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/42.3.321

Izquierdo M, Duque G, Morley JE (2021) Physical activity guidelines for older people: knowledge gaps and future directions. Lancet Healthy Longev 2:e380–e383. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-7568(21)00079-9

McAuley E, Szabo A, Gothe N et al (2011) Self-efficacy: implications for physical activity, function, and functional limitations in older adults. Am J Lifestyle Med. https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827610392704

Chung S, Kim J (2021) The effects of intergenerational program on solidarity and perception to other generations in Korea. J Soc Serv Res 47:219–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2020.1744501

Belgrave MJ, Keown DJ (2018) Examining cross-age experiences in a distance-based intergenerational music project: comfort and expectations in collaborating with opposite generation through “virtual” exchanges. Front Med 5:214. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2018.00214

Sun Q, Lou VW, Dai A et al (2019) The effectiveness of the young-old link and growth intergenerational program in reducing age stereotypes. Res Soc Work Pract 29:519–528. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731518767319

Varma VR, Tan EJ, Gross AL et al (2016) Effect of community volunteering on physical activity: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med 50:106–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.06.015

Gobbi S, Sebastião E, Papini CB et al (2012) Physical inactivity and related barriers: a study in a community dwelling of older Brazilians. J Aging Res 2012:685190. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/685190

Arazi H, Izadi M, Kabirian H (2022) Interactive effect of socio-eco-demographic characteristics and perceived physical activity barriers on physical activity level among older adults. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act 19:8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11556-022-00288-y

Marquez DX, Aguiñaga S, Castillo A et al (2020) ¡Ojo! What to expect in recruiting and retaining older Latinos in physical activity programs. Transl Behav Med 10:1566–1572. https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/ibz127

Lachman ME, Lipsitz L, Lubben J et al (2018) When adults don’t exercise: behavioral strategies to increase physical activity in sedentary middle-aged and older adults. Innov Aging 2:igy007. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igy007

Cohen-Mansfield J (2022) Motivation to participate in intergenerational programs: a comparison across different program types and generations. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19:3554. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063554

May T, Dudley A, Charles J et al (2020) Barriers and facilitators of sport and physical activity for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and adolescents: a mixed studies systematic review. BMC Public Health 20:601. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8355-z

Brown HE, Atkin AJ, Panter J et al (2016) Family-based interventions to increase physical activity in children: a systematic review, meta-analysis and realist synthesis. Obes Rev Off J Int Assoc Study Obes 17:345–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12362

Jarrott SE, Scrivano RM, Park C et al (2021) Implementation of evidence-based practices in intergenerational programming: a sco** review. Res Aging 43:283–293. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027521996191

Giraudeau C, Bailly N (2019) Intergenerational programs: what can school-age children and older people expect from them? A systematic review. Eur J Ageing 16:363–376. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-018-00497-4

Granacher U, Muehlbauer T, Gollhofer A et al (2011) An intergenerational approach in the promotion of balance and strength for fall prevention—a mini-review. Gerontology 57:304–315. https://doi.org/10.1159/000320250

Mannion G (2016) Intergenerational education and learning: we are in a new place. In: Punch S, Vanderbeck R, Skelton T (eds) Families, intergenerationality, and peer group relations. Springer, Singapore, pp 1–21

Gagliardi AR, Morrison C, Anderson NN (2022) The design and impact of culturally-safe community-based physical activity promotion for immigrant women: descriptive review. BMC Public Health 22:430. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12828-3

Aspvik NP, Viken H, Ingebrigtsen JE et al (2018) Do weather changes influence physical activity level among older adults?—The generation 100 study. PLoS ONE 13:e0199463. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0199463

Klimek M, Peter RS, Denkinger M et al (2022) The relationship of weather with daily physical activity and the time spent out of home in older adults from Germany—the ActiFE study. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act 19:6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11556-022-00286-0

Barnett DW, Barnett A, Nathan A et al (2017) Built environmental correlates of older adults’ total physical activity and walking: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 14:103. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-017-0558-z

Lin D, Cui J (2021) Transport and mobility needs for an ageing society from a policy perspective: review and implications. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211802

Hamer O, Larkin D, Relph N et al (2021) Fear-related barriers to physical activity among adults with overweight and obesity: a narrative synthesis sco** review. Obes Rev Off J Int Assoc Study Obes 22:e13307. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13307

Anderson-Hanley C, Arciero PJ, Brickman AM et al (2012) Exergaming and older adult cognition: a cluster randomized clinical trial. Am J Prev Med 42:109–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.016

Phang JK, Kwan YH, Yoon S et al (2023) Digital intergenerational program to reduce loneliness and social isolation among older adults: realist review. JMIR Aging 6:e39848. https://doi.org/10.2196/39848

Chao Y-Y, Scherer YK, Montgomery CA (2015) Effects of using Nintendo Wii™ exergames in older adults: a review of the literature. J Aging Health 27:379–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264314551171

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge all participants who participated in the studies included in the systematic review as well as the authors who provided the original data for their help in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the Key Research Project of the Sichuan Nursing Association [H22009]; the Sichuan Provincial Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine Research Project [2021MS095].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FZ: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, and writing—original draft. HZ: conceptualization, methodology, and data curation—original draft. HYW: investigation and supervision. LFL: investigation and supervision. XZ: writing—review & editing, and funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors state that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Statement of human and animal rights

This article does not include human or animal participants nor violated their rights.

Informed consent

Informed consent was not required for this type of study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A: Search strategy and results

Number of citations by each database register searched

Databases | Citations |

|---|---|

Web of Science | 817 |

Embase | 364 |

PubMed | 339 |

CINAHL | 63 |

Cochrane | 84 |

SCOPUS | 15 |

Chinese Biomedical | 2 |

China National Knowledge Infrastructure | 0 |

PsycINFO | 23 |

WANFANG | 560 |

Total (databases) | 2267 |

Full search strategy for each database

PubMed

((intergeneration*[Title/Abstract] OR cross-generation*[Title/Abstract] OR civic engagement[Title/Abstract] OR intergenerational programs[Title/Abstract]) AND (older adult[Title/Abstract] OR elder*[Title/Abstract] OR senior[Title/Abstract] OR aged[Title/Abstract] OR ag?ing[Title/Abstract] OR older person[Title/Abstract] OR older people[Title/Abstract])) AND (activ*[Title/Abstract] OR exercis*[Title/Abstract] OR physical activity[Title/Abstract] OR physical behavior[Title/Abstract] OR fitness[Title/Abstract]).

EMBASE

(intergeneration*:ab,ti OR 'cross generation*':ab,ti OR 'civic engagement':ab,ti OR 'intergenerational programs':ab,ti) AND ('older adult':ab,ti OR elder*:ab,ti OR senior:ab,ti OR ag?ing:ab,ti OR aged:ab,ti OR 'older person':ab,ti OR 'older people':ab,ti) AND (activ*:ab,ti OR exercis*:ab,ti OR 'physical activity':ab,ti OR 'physical behavior':ab,ti OR fitness:ab,ti).

Cochrane

Intergeneration* OR cross-generation* OR civic engagement OR intergenerational programs in Title Abstract Keyword AND older adult OR elder* OR senior OR aged OR ag?ing OR aged OR older person OR older people in Title Abstract Keyword AND activ* OR exercis* OR physical activity OR physical behavior OR fitness in Title Abstract Keyword—(Word variations have been searched).

Web of science

Intergeneration* OR cross-generation* OR civic engagement OR intergenerational programs (Topic) and older adult OR elder* OR senior OR aged OR ag?ing OR aged OR older person OR older people (Topic) and activ* OR exercis* OR physical activity OR physical behavior OR fitness (Topic).

SCOPUS

(TITLE-ABS-KEY ( intergeneration* OR cross-generation* OR civic AND engagement OR intergenerational AND programs) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( older AND adult OR elder* OR senior OR aged OR ag?ing OR aged OR older AND person OR older AND people) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( activ* OR exercis* OR physical AND activity OR physical AND behavior OR fitness)).

CINAHL

AB (intergeneration* OR cross-generation* OR civic engagement OR intergenerational programs) AND AB (older adult OR elder* OR senior OR aged OR ag?ing OR aged OR older person OR older people) AND AB (activ* OR exercis* OR physical activity OR physical behavior OR fitness).

PsycInfo

Abstract: intergeneration* OR Abstract: cross-generation* OR Abstract: civic engagement OR Abstract: intergenerational programs AND Abstract: older adult OR Abstract: elder* OR Abstract: senior OR Abstract: aged OR Abstract: ag?ing OR Abstract: aged OR Abstract: older person OR Abstract: older people AND Abstract: activ* OR Abstract: exercis* OR Abstract: physical activity OR Abstract: physical behavior OR Abstract: fitness.

China national knowledge infrastructure

(主题 = 代际 OR 跨代 OR 代际项目 OR 代际融合) AND (主题 = 老年 OR 老年人) AND (主题 = 运动 OR 锻炼 OR 活动).

WANFANG

主题:(代际 OR 代际支持 OR 跨代 OR 代际融合) and 主题:(老年 OR 老年人) and 主题:(运动 OR 锻炼 OR 活动).

Chinese biomedical

("代际"[摘要:智能] OR "代际支持"[摘要:智能] OR "跨代"[摘要:智能] OR "代际融合"[摘要:智能]) AND( "老年"[标题:智能] OR "老年人"[标题:智能]) AND( "运动"[标题:智能] OR "锻炼"[标题:智能] OR "活动"[标题:智能]).

Appendix B: Study quality appraisal

See Table 3.

Appendix C: Overview of facilitators and barriers in relation to (sub)themes within the social–ecological model

See Table 4.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, F., Zhang, H., Wang, H.Y. et al. Barriers and facilitators to older adult participation in intergenerational physical activity program: a systematic review. Aging Clin Exp Res 36, 39 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-023-02652-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-023-02652-z