Abstract

Introduction

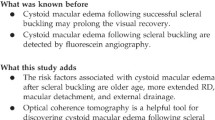

This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of cystoid macular edema after pars plana vitrectomy for the treatment of pseudophakic rhegmatogenous retinal detachment and identify possible related risk factors.

Methods

A retrospective monocentric study was conducted within a cohort of pseudophakic patients undergoing vitrectomy for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment between January 2019 and December 2022. Demographic data, initial and intraoperative characteristics of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, and postoperative data were analyzed. Cystoid macular edema was defined on optical coherence tomography exclusively.

Results

A total of 164 eyes of 164 patients were included for analysis. The mean age of the patients at surgery was 65.7 ± 12.0 years. The mean best-corrected visual acuity was 2.1 ± 1.0 logMAR preoperatively and 1.0 ± 0.7 logMAR postoperatively. The mean follow-up was 13.4 ± 7.7 months. The prevalence of cystoid macular edema was 17.1% [9.8–26.4]. In multivariate analysis, severe proliferative vitreoretinopathy (relative risk 3.6 [1.3–9.7]) and laser retinopexy (relative risk 8.4 [1.1–64.7]) were independently and significantly associated with cystoid macular edema.

Conclusion

The prevalence of cystoid macular edema in pseudophakic rhegmatogenous retinal detachment after pars plana vitrectomy was 17.1%. Severe proliferative vitreoretinopathy stage and the use of endolaser retinopexy were independent risk factors for development of cystoid macular edema.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Despite the recent improvements in surgical techniques, cystoid macular edema remains one of the primary causes of vision impairment after both cataract surgery and vitrectomy. |

To date, few data are available on the prevalence of cystoid macular edema after pars plana vitrectomy for the treatment of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. |

In the present study, the prevalence of cystoid macular edema following pars plana vitrectomy for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment in pseudophakic patients was 17.1%. |

High grade of proliferative vitreoretinopathy and laser retinopexy were associated with the development of cystoid macular edema. |

Cryoretinopexy might be advantageous over laser retinopexy in order to reduce the occurrence of postoperative cystoid macular edema. |

Introduction

Surgical techniques in vitreoretinal surgery have benefited from significant advances in recent years [1, 2]. In particular, the development of minimally invasive pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) has allowed the use of small diameter trocars, in particular 25 and 27 gauge, and transconjunctival valves that do not require scleral suture [1, 2]. Furthermore, modern visualization systems allow easy visualization of the retinal periphery and at the same time high-level detail of the posterior pole [1, 2]. These improvements made it possible to reduce conjunctival trauma and scleral manipulation along with postoperative inflammation and patient discomfort [3, 4]. Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD) surgery has equally benefited from these technological advances [5, 6]. However, postoperative complications still persist following these procedures and are associated with poor visual recovery [7, 8]. Cystoid macular edema (CME) is a primary cause of visual impairment after both successful cataract and vitreoretinal surgeries [7, 8]. Its prevalence and risk factors after cataract surgery have been largely investigated [9,10,11]. According to recent studies, CME occurs in 0.1–2.3% of patients after phacoemulsification and is associated with various risk factors such as vitreous loss, iris trauma, and posterior capsule rupture [9,10,11]. To date, few data are available on the prevalence of CME following PPV for RRD. Since cataract development is a common complication after PPV with the use of endotamponade agents, it is difficult to define the cause of CME as it can be consecutive to both RRD procedure and secondary cataract surgery [12, 13]. Moreover, a history of RRD has been shown to be an independent risk factor of CME after cataract surgery [14]. Thus, the aim of this study was to identify the prevalence of postoperative CME in pseudophakic patients with RRD treated by PPV and to evaluate potential risk factors.

Methods

Design and Patients

This retrospective, single-center study included pseudophakic patients treated for RRD at the OphtalmoPole de Paris, Hôpital Cochin (Paris, France) between January 2019 and December 2022. Institutional review board approvals for retrospective chart reviews were obtained commensurate with the respective institutional requirements prior to the beginning of the study. Described research was approved by the ethics committee of the French Society of Ophthalmology (IRB 00008855) and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Consecutive pseudophakic patients that underwent uneventful PPV for RRD were screened for enrollment. Exclusion criteria were a follow-up of less than 12 months, any previous vitreoretinal, complicated cataract surgery, ab externo approach, ocular trauma, uveitis, recurrence of the disease, any pre-existing ocular disease (e.g., amblyopia, diabetic retinopathy, retinal dystrophy, central serous chorioretinopathy, and glaucoma) and previous laser treatment. Furthermore, patients with macular edema in the preoperative optical coherence tomography (OCT) scan were also excluded.

Surgical Procedure

All the procedures were performed under regional anesthesia with peribulbar injection of 6 mL of 2% xylocaine and 2 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine. Three-port 25-gauge PPV was performed using the Alcon Constellation system (Alcon Laboratories, Inc, Forth Worth, TX) or Stellaris Elite System (Bausch & Lomb, St. Louis, MO, USA) and a wide-angle viewing lens. After central and peripheral vitreous removal, all eyes underwent 360° scleral indentation to shave the vitreous base up to the ora serrata, followed by the removal of vitreous tractions from retinal tears. Patients presenting with proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR) grade greater than B underwent retinal fold removal. According to surgeon’s preference, perfluorocarbon liquid (PFCL) was used in selected cases. Subsequently, a complete fluid–air exchange was performed, and subretinal fluid was aspirated with a flute needle. Patients underwent either trans-scleral cryopexy or endolaser to achieve retinopexy under air. The sclerotomy was closed at surgeon’s discretion with 8.0 Vicryl to avoid gas leakage. At the end of the procedure patients had either silicone or a gas tamponade (20% SF6, 17% C2F6, 14% C3F8). All the patients were required to adopt a facedown positioning for 6 h. Anatomically, successful surgery was defined as the complete disappearance of subretinal fluid and flattening of the entire circumference of the retinal breaks. Eye drops containing brinzolamide 10 mg/ml and timolol maleate 5 mg/ml, two times a day, were prescribed after surgery to all patients to lower intraocular pressure (IOP) and were discontinued after 1 month if IOP was normal. Follow-up visits were scheduled at days 1 and 7 after the surgery and 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after the surgery.

Data Collection

The following data were collected: Epidemiological characteristics including age, sex, and ophthalmological history (high myopia, glaucoma, and other ocular diseases); Preoperative evaluation including best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) in Snellen, IOP with Goldmann applanation tonometer, slit lamp biomicroscopy, and fundus examination with accurate evaluation of the peripheral retina using a three-mirror lens. In addition, the presence of vitreous hemorrhage, PVR, the extent of RRD in quadrants, the status of the macula, and the number of retinal breaks were noted. Intraoperative procedures including use of PFCL, type of retinopexy (cryo or laser therapy), tamponade (silicon oil or gas including 20% SF6, 17% C2F6, and 14% C3F8) were also were retrieved from medical records. Postoperative evaluations were performed at 1 and 7 days and 1, 3, 6, and 12 months following the surgical procedure and included BCVA in Snellen, IOP with Goldmann applanation tonometer, occurrence of complications on fundus or OCT examination, presence of epiretinal membrane (ERM), and recurrence and existence of PVR. For statistical analysis, Snellen ratios were converted to logMAR (logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution) decimal values [15]. The grade of PVR was staged according with the Retinal Society classification [16].

A spectral domain OCT (SD-OCT, Spectralis Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg Germany) scan encompassing the macula was performed at each visit and CME was defined as more than three circular or ovoid intraretinal hyporeflective spaces in the inner and/or outer layers in the central millimeter of the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study grid. The presence of CME was evaluated by two independent observers (I.M. and F.B).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.4 statistical software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Quantitative data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), qualitative data with confidence intervals of ± 95%. The Shapiro–Wilk’s test was used to assess normality of data. Comparisons of quantitative data were performed using the Wilcoxon signed rank test or Student’s t test. Comparisons of qualitative data were performed using the chi-square test or the Fisher’s exact test when appropriate. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. To identify risk factors of the occurrence of CME we compared the clinical and paraclinical characteristics of the patients who presented this complication to those who did not. All variables with a P value less than 0.15 in univariate analysis or clinically relevant according to investigators and literature data were included in a multivariate logistic regression model.

Results

Of the 657 patients who underwent surgical procedure for RRD during the study period, 408 were phakic at baseline and not eligible. Of the 249 pseudophakic patients, 85 were excluded for the following reasons: ab externo approach (n = 13), history of ocular trauma (n = 16), recurrence of RRD (n = 9), and less than 12 months of postoperative follow-up (n = 47).

Finally, a total of 164 eyes of 164 pseudophakic patients including 62 women and 102 men were included in the study. The mean time between cataract surgery and retinal detachment was 39.0 ± 26.9 months. Demographic and baseline characteristics are reported in Table 1.

The mean age at surgery was 65.7 ± 12.0 years. The mean follow-up time was 13.4 ± 7.7 months. The mean BCVA was 2.1 ± 1.0 logMAR preoperatively and 1.0 ± 0.7 logMAR postoperatively.

During follow-up period 28 of 164 eyes (17.1% [9.8–26.4]) had CME. Median time to onset of CME was 2.8 months (interquartile range [1.8–6.3]).

Of the 164 patients included in the study, 36 (22%) received trans-scleral cryotherapy and 128 (78%) received retinopexy by endolaser. Among patients who received cryotherapy, one patient (2.7%) developed CME. Among those who received endolaser, 27 (21%) developed CME. Eight patients underwent posterior retinotomy during the surgical procedure. None of these patients developed macular edema. Six patients received internal limiting membrane (ILM) peeling in the setting of eyes with PVR > B with macular pucker. These such patients developed CME.

During the follow-up, 56 patients (34.1%) developed ERM. Of these, 13 had concomitant CME.

Univariate analysis showed that the variables statistically associated with CME were (1) PVR > B (32.1% [14.8–49.4] vs. 10.3% [5.2–15.4]; P = 0.003) and (2) retinopexy performed by endolaser (96.4% [89.6–100.0] vs. 74.3% [66.9–81.6; P = 0.009]). The presence of a macula off RRD was not significantly different between the two groups (61.8% [53.6–69.9] in the group without CME and 53.6% [35.1–72.0] in the group with CME; P = 0.4) as well as in the time from the loss of central vision to surgery (3.8 ± 3.9 days in the group without CME and 2.3 ± 1.5 days in the group with CME, P = 0.44) and in the type of endotamponade agent (P = 0.11).

A multivariate analysis using a logistic regression model was performed with adjustment for PVR > B, retinopexy by endolaser, and the presence of more than one retinal tear. The presence of more than one retinal tear was used in the multivariate analysis to investigate the role of endolaser independently, as surgeons are more like to do endolaser retinopexy when a high number of retinal tears is present. The results of the multivariate analysis are reported in Table 2. The presence of PVR > B and a retionopexy performed by endolaser were significantly associated with CME (relative risk 3.6 [1.3–9.7]) and 8.4 [1.1–64.7], respectively).

Discussion

The development of small-diameter, sutureless PPV provided advantages to both surgeons and patients, allowing shorter operating time, less surgical trauma, decreased postoperative discomfort, and faster visual recovery. However, postoperative complications may occur despite anatomically successful RRD repair, resulting in patients’ visual impairment. CME after PPV is one of the main postoperative complications leading to reduced vision after surgery [1,2,3].

The pathophysiology of CME post RRD repair remains unclear. The most plausible theory refers to an inflammatory reaction since cytokines and prostaglandins have been found to be increased in such patients. These could lead to a breakdown of the blood–aqueous barrier and consequent fluid accumulation [17].

To date, few authors evaluated the prevalence and risk factors of postoperative CME after RRD repair with PPV [18]. Recently, three studies showed a prevalence between 10% and 17% of patients undergoing PPV [17,18,19]. Our results are in agreement with those reported. In particular, in the present study CME occurred in 17.1% of the operated eyes.

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first one including only pseudophakic patients. This is a crucial element that allowed us to exclude an important bias of CME related to cataract surgery. In fact, the development of cataract after PPV for RRD is very common and is strongly related to the interaction between the posterior lens surface and tamponade agents [12, 13]. Thus, the cause of the CME can be difficult to identify, as it can be consecutive either to RRD or to subsequent cataract surgery. Indeed, Merad et al. demonstrated that cataract surgery performed within 6 months of PPV for RRD was significantly associated with CME in multivariate analysis [19]. Furthermore, Starr et al. showed that the most important risk factors for CME following RRD repair were subsequent cataract surgery and recurrent RRD [18]. Thus, the state of the lens plays a key role in the evaluation of risk factors of postvitrectomy CME and it must be taken into account to perform an accurate analysis.

In the present study, a multivariate analysis showed two independent risk factors associated with the occurrence of CME, in particular the presence of severe PVR and the use of laser retinopexy. Our results are consistent with previous studies that investigated the development of CME after PPV showing that PVR is one of the major risk factors involved [17,18,19]. Additionally, three studies that exclusively included RRD with severe stages of PVR showed higher rates of CME, ranging from 33% to 52% [20,21,22]. This finding confirms the role of inflammation as a leading process involved in CME development since PVR occurs in response to tissue damage caused by RRD and subsequent inflammatory reaction [19, 23, 24]. It has been shown that several inflammatory cells and cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), interferon gamma (IFNγ), and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), are involved in PVR development [25,26,27,28]. Inflammatory mediators lead to a breakdown of the blood–retinal barrier and blood–aqueous barrier, causing an increased vascular permeability [29, 30]. Interestingly, these pro-inflammatory factors were also found in higher concentrations in the aqueous humor of patients with CME after cataract surgery [30].

In the present study, the use of endolaser retinopexy was associated with a significantly higher risk of postoperative CME compared to cryotherapy retinopexy. Recently, Merad et al. reported the same finding investigating risk factors for CME after PPV for RRD in a cohort of both phakic and pseudophakic patients [19]. In that study, laser retinopexy was used only for severe RRD with multiple retinal breaks, while cryotherapy was used for less extensive or single-break detachments [19]. Thus, those authors hypothesized that the CME is mainly related to the extensive use of retinopexy for the treatment of these types of RRD rather than the type of retinopexy itself [19].

To avoid this bias and to investigate the use of laser retinopexy as an independent risk factor regardless the extension of RRD, we included the number of retinal breaks in the multivariate analysis. Interestingly we found that laser retinopexy was an independent risk factor for the development of CME.

The mechanism of post-laser macular edema remains still unclear. Previous studies that investigated this issue suggested that autoregulatory changes in distribution of retinal blood flow could be involved in this pathogenesis [31, 32]. In particular, retinal photocoagulation seems to raise inner retinal oxygen levels by destroying photoreceptors. This would result in an arteriolar vasoconstriction and a reduction in blood flow to the treated midperipheral retina, causing an increased blood flow to the macula. It is possible that if the increased flow exceeds the ability of the macular arterioles to self-regulate, edema may occur [32].

As might be expected some patients developed ERM after the surgical procedure. The rate of patients who developed this complication was in agreement with that reported in previous studies [33]. This finding is not surprising since it is known that the two complications share pathogenic mechanisms and risk factors [33]. It is possible that in some eyes the presence of CME was in part related to a traction exerted by the ERM. However, only less than half of the eyes with CME had this complication.

The present study has several strengths such as the large sample size, the long follow-up period, and the fact that only pseudophakic patients were included. However, it suffers from some limitations that need to be acknowledged. In particular, its retrospective nature may have resulted in selection or indication bias, making it difficult to obtain definitive conclusions. Furthermore, our definition of CME was based exclusively on SD-OCT and not on fluorescein angiography, which still remains the gold standard for some authors. Thus, the rate of CME might include both inflammatory CME with intraretinal leakage on dye angiography and macular cystoid degeneration without intraretinal leakage [34, 35]. However, our strict criteria for including patients with CME, as well as double reading of OCT, limit this possibility.

Conclusion

CME represents a significant side effect after PPV for the treatment of RRD that could lead to a lack of visual recovery. Evaluation of the macula with SD-OCT plays a key role in the follow-up of patients after PPV, particularly those with severe PVR, as they are at higher risk of develo** CME. Additionally, our results suggest that cryoretinopexy might be advantageous over the laser retinopexy in order to reduce the risk of postoperative CME. A better knowledge of the risk factors of CME after PPV would improve the understanding of the pathophysiology in order to find a prevention to reduce the visual consequences of this complication.

References

Fabian ID, Moisseiev J. Sutureless vitrectomy: evolution and current practices. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95:318–24.

Gupta OP, Weichel ED, Regillo CD, et al. Postoperative complications associated with 25-gauge pars plana vitrectomy. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2007;38:270–5.

Recchia FM, Scott IU, Brown GC, Brown MM, Ho AC, Ip MS. Small-gauge pars plana vitrectomy: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1851–7.

Lakhanpal RR, Humayun MS, De Juan E, et al. Outcomes of 140 consecutive cases of 25-gauge transconjunctival surgery for posterior segment disease. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:817–24.

Miller DM, Riemann CD, Foster RE, Petersen MR. Primary repair of retinal detachment with 25-gauge pars plana vitrectomy. Retina. 2008;28:931–6.

Wimpissinger B, Kellner L, Brannath W, et al. 23-Gauge versus 20-gauge system for pars plana vitrectomy: a prospective randomised clinical trial. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:1483–7.

Gharbiya M, Grandinetti F, Scavella V, et al. Correlation between spectral-domain optical coherence tomography findings and visual outcome after primary rhegmatogenous retinal detachment repair. Retina. 2012;32:43–53.

Kiss CG, Richter-Müksch S, Sacu S, Benesch T, Velikay-Parel M. Anatomy and function of the macula after surgery for retinal detachment complicated by proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144(6):872–77.

Zur D, Loewenstein A. Postsurgical cystoid macular edema. Dev Ophthalmol. 2017;58:178–90.

Henderson BA, Kim JY, Ament CS, Ferrufino-Ponce ZK, Grabowska A, Cremers SL. Clinical pseudophakic cystoid macular edema. Risk factors for development and duration after treatment. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007;33:1550–8.

McCafferty S, Harris A, Kew C, et al. Pseudophakic cystoid macular edema prevention and risk factor; prospective study with adjunctive once daily topical nepafenac 0.3% versus placebo. BMC Ophthalmol. 2017;17(1):16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-017-0405-7.

Chang S, Lincoff HA, Coleman DJ, Fuchs W, Farber ME. Perfluorocarbon gases in vitreous surgery. Ophthalmology. 1985;92:651–6.

Kim RW, Baumal C. Anterior segment complications related to vitreous substitutes. Ophthalmol Clin N Am. 2004;17:569–76.

Chu CJ, Johnston RL, Buscombe C, Sallam AB, Mohamed Q, Yang YC. Risk factors and incidence of macular edema after cataract surgery: a database study of 81984 eyes. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:316–23.

Holladay JT. Visual acuity measurements. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2004;30:287–90.

Machemer R, Aaberg TM, Freeman HM, Irvine AR, Lean JS, Michels RM. An updated classification of retinal detachment with proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;112:159–65.

Chatziralli I, Theodossiadis G, Dimitriou E, Kazantzis D, Theodossiadis P. Macular edema after successful pars plana vitrectomy for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: factors affecting edema development and considerations for treatment. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2021;29:187–92.

Starr MR, Cai L, Obeid A, et al. Risk factors for presence of cystoid macular edema following rhegmatogenous retinal detachment surgery. Curr Eye Res. 2021;46:1867–75.

Merad M, Vérité F, Baudin F, et al. Cystoid macular edema after rhegmatogenous retinal detachment repair with pars plana vitrectomy: rate, risk factors, and outcomes. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4914. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11164914.

Stopa M, Kociȩcki J. Anatomy and function of the macula in patients after retinectomy for retinal detachment complicated by proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2011;21:468–72.

Odrobina DC, Michalewska Z, Michalewski J, Nawrocki J. High-speed, high-resolution spectral optical coherence tomography in patients after vitrectomy with internal limiting membrane peeling for proliferative vitreoretinopathy retinal detachment. Retina. 2010;30:881–6.

Bonnet M. Macular changes and fluorescein angiographic findings after repair of proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Retina. 1994;14:404–10.

Pastor JC, Rojas J, Pastor-Idoate S, Di Lauro S, Gonzalez-Buendia L, Delgado-Tirado S. Proliferative vitreoretinopathy: a new concept of disease pathogenesis and practical consequences. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2016;51:125–55.

Kishikawa Y, Gong H, Kitaoka T, et al. Elements and organic substances analyzed with a time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometer in the internal limiting membrane of macular hole. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:4953–4953.

Dai Y, Wu Z, Wang F, Zhang Z, Yu M. Identification of chemokines and growth factors in proliferative diabetic retinopathy vitreous. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:486386. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/486386.

El-Ghrably IA, Dua HS, Orr GM, Fischer D, Tighe PJ. Intravitreal invading cells contribute to vitreal cytokine milieu in proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:461–70.

Campochiaro PA. Pathogenic mechanisms in proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115:237–41.

Mitamura Y, Takeuchi S, Yamamoto S, et al. Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 levels in the vitreous of patients with proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2002;46:218–21.

Kon CH, Occleston NL, Aylward GW, Khaw PT. Expression of vitreous cytokines in proliferative vitreoretinopathy: a prospective study. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:705–12.

Chu L, Wang B, Xu B, Dong N. Aqueous cytokines as predictors of macular edema in non-diabetic patients following uncomplicated phacoemulsification cataract surgery. Mol Vis. 2013;19:2418.

Nonaka A, Kiryu J, Tsujikawa A, et al. Inflammatory response after scatter laser photocoagulation in nonphotocoagulated retina. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:1204–9.

McDonald HR, Schatz H. Macular edema following panretinal photocoagulation. Retina. 1985;5:5–10.

Banker TP, Reilly GS, Jalaj S, Weichel ED. Epiretinal membrane and cystoid macular edema after retinal detachment repair with small-gauge pars plana vitrectomy. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2015;25:565–70.

Coscas G, Cunha-Vaz J, Soubrane G. Macular edema: definition and basic concepts. Dev Ophthalmol. 2010;47:1–9.

Pole C, Chehaibou I, Govetto A, Garrity S, Schwartz SD, Hubschman JP. Macular edema after rhegmatogenous retinal detachment repair: risk factors, OCT analysis, and treatment responses. Int J Retina Vitreous. 2021;7:9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40942-020-00254-9.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This research received no external funding. The journal’s Rapid Service Fee was funded by the authors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Federico Bernabei, Ianis Marcireau, Pierre-Raphaël Rothschild; Methodology: Federico Bernabei, Ianis Marcireau, Pierre-Raphaël Rothschild; Formal analysis and investigation: Federico Bernabei, Ianis Marcireau, Francesca Frongia, Frederic Azan, Aldo Vaggi, Enrico Peiretti, Gilles Guerrier, Pierre-Raphaël Rothschild; Writing—original draft preparation: Federico Bernabei, Ianis Marcireau, Francesca Frongia, Frederic Azan, Aldo Vaggi, Enrico Peiretti, Gilles Guerrier, Pierre-Raphaël Rothschild; Writing—review and editing: Federico Bernabei, Ianis Marcireau, Francesca Frongia, Frederic Azan, Aldo Vaggi, Enrico Peiretti, Gilles Guerrier, Pierre-Raphaël Rothschild.

Disclosures

Federico Bernabei, Ianis Marcireau, Francesca Frongia, Frederic Azan, Aldo Vagge, Enrico Peiretti, Gilles Guerrier, Pierre-Raphaël Rothschild declare that they have no competing interests.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Institutional review board approvals for retrospective chart reviews were obtained commensurate with the respective institutional requirements prior to the beginning of the study. Described research was approved by the ethics committee of the French Society of Ophthalmology (IRB 00008855) and adhered to the tenets of the declaration of Helsinki.

Data Availability

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bernabei, F., Marcireau, I., Frongia, F. et al. Risk Factors of Cystoid Macular Edema After Pars Plana Vitrectomy for Pseudophakic Retinal Detachment. Ophthalmol Ther 12, 1737–1745 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40123-023-00705-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40123-023-00705-0