Abstract

Beyond the notion of decision-making of career choice just being rational, this article proposes the primacy of ‘affect’ in the decision to become teachers over time. The article explores the becoming of immigrant English language teachers as an identity formation process, focusing on the lived experiences of 16 English language teachers since early childhood, mostly prior to their migration to Australia. Findings of the hermeneutic phenomenological narrative analysis of the teachers’ reflective accounts revealed two lines of becoming and their intersections—the line of becoming an English language learner and the line of becoming an English language teacher through decision-making for career choice. The histories of their initial professional decision to ‘become’ English teachers demonstrate the interplay of socially produced desires and personal investment in professional learning and capabilities since early childhood. Through unravelling the assemblages within which their desires to become teachers were fomented and strengthened through embodied lived experiences over a long period of time, we argue that the concept of English teachers’ ‘desired becoming’ informed their initial and long-term decision about career choice. This notion provides a window into the teachers’ decision-making of career choice in terms of the formation of their professional identities as an interplay of the affective and the rational. Embracing and appreciating the combined role of the affective and the rational in teachers’ becoming is important to consider in future research in this area as well as for teacher recruitment and retention, hence potentially addressing critical teacher shortages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Becoming an English teacher

How one makes the decision to choose a career may not always have a straight-forward answer. Some may choose a career based on self-concept, interest, motivation, and aptitude, or by analysing available opportunities and the values attached to these. According to social cognitive career theory, variables of self-efficacy shape career aspirations and trajectories (Lent et al., 1994). It has been argued that one’s interest in and selection of a future career emerge through the accumulative formation of beliefs, capacities, abilities and values (Lent et al., 1994). From the perspective of motivation theory, people choose careers based on their internal and external ‘needs’. Motivation theories of work (Locke & Latham, 2004) suggest that workers rationalise career decisions based on the motivational factors, drivers and triggers that shape their work roles and commitments. From these perspectives, career choice lies in the individual’s expectations for success in a profession and the value they assign to that profession (Wigfield & Eccles, 2000).

In the teacher education field to date, research concerning career choice—most of which is quantitative—has principally focused on internal and/or external motivational factors contributing to teachers’ decision-making about career (Heinz, 2015). This research tradition aims to establish causal relationships between factors, drivers, triggers, and decision-making. Self-beliefs, prior experiences and other socio-cultural influences may contribute to teachers’ career decisions (Heinz, 2015). Most research has been conducted via the FIT-Choice test (Richardson & Watt, 2006), underpinned by expectancy value theory to understand motivational influences which contribute to professional choice (Wigfield & Eccles, 2000). Motivational factors have been classified as intrinsic, altruistic and extrinsic (Heinz, 2015; Yüce et al., 2013). Intrinsic motivation involves passion for the profession, aptitude in teaching and personal fulfilment (Lovett, 2007; Manuel & Hughes, 2006; Yüce et al., 2013). Altruistic motivation is the intention to make a difference in communities and society (Chong & Low, 2009). Extrinsic motivations include job security (Jungert et al., 2014; Lam, 2012), high salary or reliable income, and long vacations (Lai et al., 2005; Lam, 2012; Struyven et al., 2013). Other factors of relevance are prior teaching and learning experiences (Heinz, 2011, 2013), initial teacher education (Manuel & Hughes, 2006), demographic characteristics (Yüce et al., 2013), and considering teaching as a fall-back career (Cross & Ndofirepi, 2015).

A literature search on ‘becoming a teacher’ appeared mostly to focus on the initial decision-making of becoming a teacher and remaining in the profession. Similar to the literature already reviewed, this group of literature predominantly emphasises the working of the mind alone to become a teacher, especially motivation, informed decision-making, rational choice, etc. (e.g., Bruinsma & Jansen, 2010; Caires et al., 2012; Simonsz et al., 2023; Thornberg et al., 2023; Wolf et al., 2021). However, some research highlighted the role of the long-term embodied lived experiences in career decisions to become teachers. A study of 102 students conducted over time in the Australian rural context examining what it meant for them to become teachers in terms of their goals and aspirations found that the graduates’ deep values attached to their teacher education, credentials and initial professional experiences over years informed their desire to establish themselves and remain in the profession. Nonetheless, their convictions often wavered due to the contractual status of their profession (Plunkett & Dyson, 2011). A US study on a white science teacher’s becoming (identity) revealed how the social texts of her teacher education programme interplayed with her lived experiences of ‘her midwestern small-town childhood and a professional life in science’ (Gomez et al., 2007, p. 2107). The study found the white teachers’ ‘ideological becoming’ was not complete and stable through teacher education and initial experiences but her becoming evolved in the critical reflexivity and fluidity of her understanding of herself and her students: ‘that collisions with ideas she has not before considered continue to disrupt and unsettle her thinking and practices’ (Gomez et al., 2007, p. 2131). Although the findings of the two studies indicate that embodied lived experiences over time impact teachers’ career choice and remaining in the profession, it is problematic that the central role of affect influencing the long-term trajectory of ELTs’ careers is still unexplored.

Additionally, notwithstanding the growing interest in the emotional aspects of teaching and teacher identity (Hargreaves, 2005; Kelchtermans & Deketelaere, 2016; Nguyen & Ngo, 2023; Oplatka, 2009; Song, 2016; Zembylas, 2015, 2006, 2021), research is yet to address broader socio-cultural constructs (Klassen et al., 2011), or to examine how multiple interplays of socio-cultural and other material forces might affect a teacher’s becoming with regard to their decision to choose teaching as a professional career. Little attention has been paid to the primacy of affect in one’s decision to become a teacher (Kövecses, 2004) as an integral part of identity formation. Indeed, the primary role of affect is central in informing the career choice by their embodied lived experiences over time. For teachers to continue develo** and remain in the profession, it is essential to deeply engage with their evolving professional identity formation process, even though it is inherently fluid and never truly complete. In order to address the issue of how a teacher chooses their career, develops their identity and remains in the profession, it is crucial to understand the pre-eminence of affective lived experiences that permeate a teacher’s decision in becoming a teacher as an identity formation.

To gain deeper understanding of the subtle influences of affective elements of lived experiences in the process of identity formation and develo** as an English language teacher (ELT) before and after migration to Australia, we adopt a Deleuzian frame. We argue that becoming a teacher is not only based on rational choices responsive to internal and external motivational factors, but also on the socio-materially produced desires that underlie choices and decision-making (Deleuze & Guattari, 1983). As we argue below, English language teachers’ (ELTs) decisions are rationalised only after affective encounters—inter-subjective and inter-objective—as they engage with the material–semiotic–affective staging of events over time in their lives. The lived experiences enmeshed with embodied elements of affect make meanings guide actions, and the ‘meaning’ itself emerges as a new emotion, making further actions possible and actual (Sampson, 2022). According to Deleuze (1994), human subjectivity is better represented relationally and dynamically as becoming (rather than being) in the continuous process of differentiated repetitions. Becoming is always in a process of movement, making new meanings using the repertoire of real and abstract—materials of the world and ideas that encircle the lifeworld.

In this paper, we examine the complexity of the factors that may shape ELT becoming (Trent, 2012) over time. We discuss the findings of a study exploring how 16 teachers became ELTs in and through various situated practices and gathering of emotional experiences since early childhood. We frame the process of becoming a teacher as non-linear over an individual’s life. In this process, motivational factors that influence teachers’ decision-making emerge as a result of socio-material affect in their lives. That is, the desire to become a teacher is affective in that it drives the bodily capacity to make decisions, melding in this process ‘personal aspiration; spiritual endeavour; social mission; intellectual pursuit; the desire for connectedness; and a belief in the power of ideas and relationships manifested in education to alter the conditions of their own and others’ lives for the better’ (Manuel & Hughes, 2006, p. 20). In this sense, the affective origin of desire flows through one’s motivation, which ‘in itself implies emotion’ (Du Toit, 2014, p. 6). Embodied desiring refers to the body’s capacity to project itself as always more than itself. The significance of this study is its provision of a decentred perspective on participants’ decision-making to become ELTs by considering the dialectical relationship between the affective and the rational in ‘the dynamic of human life’ (Vygotski, 1965 as cited in Rieber & Aaron, 1987, p. 333). The career decisions of ELTs arise from a blend of embodied lived experiences and rational thinking. Both Spinoza and Vygotsky shared a similar perspective on this, with Vygotsky noting that “consciousness is the experience of experiences (soznanie est’ perezhivanie perezhivanii)”, which aligns closely with Spinoza’s definition of consciousness as “the idea of the idea…” (Sévérac, 2017, p. 80).

Desire and becoming

In this research, the decision-making about career choices as part of the immigrant English teachers’ becoming is conceptualised as a form of ‘desired becoming’—that is, as the ‘will to power’ which is sublimated into their desires to influence and benefit others, and into a creative activity of ‘self-overcoming’ or ‘self-mastery’ (Nietzsche, 2002, 2008). In social life, power is associated with education and knowledge (Foucault, 1980), and desiring power thus can be linked with the desire to be educated (i.e., power to) and to educate others (i.e., power over). Thus, we shift the focus from pre-formed desires and the workings of reason to explore the socio-material and political becoming and the flows of desire that precede (and result from) the formation of subjects and objects. In this way, becoming an English language teacher can be traced historically to the flows of desire in and across socio-material assemblages.

According to Deleuze and Guattari (1983), an assemblage is a constellation of bodies and things that are coded by taking a particular form and occupying a particular territory. An assemblage connects material bodies and things on a horizontal axis, forming socio-material relations that become represented and meaningful as a social order(ing) of bodies, actions and reactions. One’s becoming implies a vertical axis of movement across assemblages, involving a ‘flight’ of desire across their territorial boundaries. A translation from the French agencement, assemblages are productive comings-together which channel affect, or the ‘capacity to affect or be affected’ (Fox & Alldred, 2015, p. 401). Content comprises the machinic assemblage of bodies and actions, ‘an intermingling of bodies reacting to one another’ (Deleuze & Guattari, 1988, p. 88), whereas expression is the collection assemblage of enunciation—’of acts and statements, of incorporeal transformations attributed to bodies’ (p. 88). Expression within assemblages become semiotic systems or regimes of signs, whereas content becomes pragmatic systems of actions and passions (Deleuze & Guattari, 1988, p. 504).

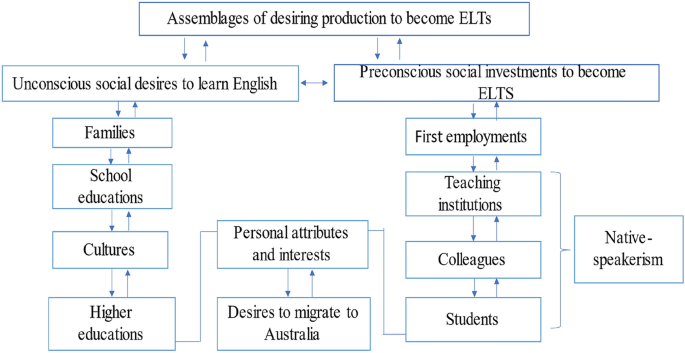

De-centring desire from the subject, while exploring decisions to become a teacher, means attending to how desire as a life force is immanently networked with other forces that are together constitutive of the social production of that desire. According to Deleuze and Guattari (1983), socio-material assemblages have ‘machinic’ rather than organic relations between the constitutive elements and, hence, there is no desire without ‘desiring-machines’ and their connective desiring production. Deleuze and Guattari (1983) differentiate in this regard between unconscious desire and preconscious social investment. While unconscious desire has to do with pre-personal creative desire, preconscious social investment is concerned with values, beliefs, and intentions.

The analysis of how socio-material assemblages may produce the desire to become an ELT responds to the differentiation between ‘the unconscious libidinal investment of group or desire, and the preconscious investment of class or interest’ (Deleuze & Guattari, 1983, p. 343). In this study, unconscious desire allows us to comprehend a free-floating desire to learn English, while preconscious social investment captures the influence of beliefs about teaching English and teaching as a career choice. The analytic also includes the affective vectors of molar and molecular lines (Deleuze & Guattari, 1988) that map the entanglement of participants’ desires in debilitating and enabling ways. Molar lines relate to the subject’s embodiment of the rigid segmentations of socio-cultural apparatuses (Deleuze & Guattari, 1988; Foucault, 2013), such as ‘native-speakerism’. Molecular lines refer to ‘a precise state of intermingling of bodies in a society, including all the attractions and repulsions, sympathies and antipathies, alterations, amalgamations, penetrations, and expansions that affect bodies of all kinds in their relations to one another’ (Deleuze & Guattari, 1988, p. 90), such as relational experiences. The functions of molecular lines can be viewed as thrusting unfolding of possibilities to ‘become’ and ‘becoming’ against the ‘pre-existing, molar, arboreal’ (Rogers et al., 2014, p. 22) structure that inhibits the process of becoming.

Context

Undertaken as part of a larger project, the study was informed by hermeneutic phenomenology and the innovated hermeneutic phenomenological narrative enquiry. In hermeneutic phenomenology, the researcher and participants engage with the research process intimately and deeply, but the researcher still seeks to interpretively understand the multi-layered meanings of the experienced phenomena in terms of their commonality of occurrence among participants (van Manen, 1990). In this study, recursive interpretations and the uses of narrative techniques were the core means to gather and interpret the complex patterns of the lived phenomena (Nigar, 2019).

Sixteen participants (see Table 1), all of whom lived in metropolitan centres in Australia at the time of data collection, participated in the study. Amongst them, four participants—Ling Ling, Becca, Quang and Raphael—had started their formal English teaching career in Australia. The others began in their countries of origin but some taught in other countries of residence too, such as United Arab Emirates (Janaki) and Uganda (Mahati). Two of them taught English to international students in their countries of origin, namely, Frida and Mandy. The interviews were conducted by the first author of this manuscript. Her emic (insider) view lay in her familiarity with some of the historical and current global contexts of research into English language learning and teaching, and almost 10 years’ of English language teaching experience. Considering her as ‘one of them’, the participants felt comfortable in telling her their stories (see Guba & Lincoln, 1994). From the etic (outsider) perspective (Olive, 2014), however, the researcher was conscious of her beliefs and assumptions, and how they might influence the interpretation of research data.

Fifteen participants flexibly wrote narratives online over a period and then took part in one-on-one interviews (one participant was only interviewed). The narratives focused on their experiences of English learning and choosing their career. The interview prompts elicited information about their family, linguistic, cultural, educational and geographic backgrounds; their English language learning experiences; their motivations to become ELTs; how they obtained their first English teaching positions; and how they remained in the profession. In addition to the online narratives and interviews, relevant data were also collated from responses to other prompts used in the main project, such as emails. The research (project ID 19107) was approved regarding ethical measures by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee. Prior to signing the consent forms, all participants were informed of the voluntary nature of the research participation and their full anonymity.

A hermeneutic phenomenological narrative method (van Manen, 1990) was adopted to sequence and analyse the data through recursive analyses and uncover the themes. The analysis aimed to reconstruct socio-material assemblages within which participants had interacted, based on the participants’ narration of their life events (Bruner, 1990). In the following sections, we present the various assemblages of desiring production which were constructed from the data; however the figure does not represent the complex and non-linear process of interactions and influence of the assemblages (Fig. 1).

Assemblages of desiring production

The participants had often ‘unconsciously’ internalised the desire to become proficient in English under the influence of more knowledgeable others (Fleer, 2021; Vygotsky, 1978). As they initially encountered the language and then began their formal education, their embodied emotional experiences and their echo in their reflections (perezhivanie) of English and English language learning worked as affective-volitional forces for them to become proficient users of the language (Vygotsky, 1999). The participants’ embodied and desired selves, shaped through these experiences, impacted their later career decisions. In what follows, we address different kinds of assemblages within which the participants operated—families, school education, culture, and higher education—and through which their desires for English were activated and mediated. They interacted with these assemblages at different times. Furthermore, the size and duration of the assemblages, and the ways in which they (re)formed participants’ desires, were quite variable.

Family assemblages

In their pre-school years, the participants’ desires for English were kindled by affective intersubjective relations and cultural objects and artefacts (Anning et al., 2008; Fleer et al., 2017). The roles of significant others (Fleer, 2021), including parents and family members, contributed to their internalisation of a passion and imagination for the language and teaching. They were exposed to English through a wide variety of popular cultures, educational materials, and practices in family settings. These included electronic media, books, and games, replete with sensory-motor impacts. Participation in activities mediated by English and associated forms of cultural artefacts, which were perceived as affective experiences (Michell, 2016)—engaging and experienced as enjoyable—drove them further to desire English proficiency.

Although formal language learning started for the participants in school, most were exposed to English in their early childhood. Twelve participants said that in their early childhood or primary school years they were also exposed to popular culture in English: literature, music, film, and television. Oksana recalled that her parents ‘listened to the Beatles songs, and since the time I was born, I was exposed to that music, and I fell in love with the language’. Similarly, Becca wrote, ‘I’ve been exposed to English as long as I can remember, and I’ve always liked it. I liked the way it sounded, I liked its “coolness” (it was the language of movies and songs)’. As a child, Frida played English board games at home; she recalled, ‘I would usually play against my grandmother and my aunts, who all had a higher level of English than my 10-year-old self, so I learned to pick up new words from them’.

As Fleer (2016) pointed out, affective environments were produced by family members and practices—ordinary emotional experiences and ways of ‘being with’ or ‘becoming with’—that led the participants to pay attention to and desire English. However, while most participants’ immediate family members explicitly and actively encouraged their education in the language, some did not (e.g., Frida has an estranged father). Janaki’s learning was interrupted by a forced marriage when she was in high school, and Mahati was also subjected to attempts to be forcibly married by family members during her higher education. Janaki reflected, ‘[i]t was after my marriage that I completed bachelor’s degree in education and a Masters in English … through Distance Education’.

In family settings, popular media and early learning activities emotionally affected the participants, activating a passion to learn English and dialogically imagine their multilingual and multicultural self (Kostogriz, 2005). Their socio-culturally internalised sensory-motor experiences of cultural elements during early childhood (Fleer et al., 2017; Vygotsky, 1987) were later rationalised as their affective and passionate attachments to English.

School education as assemblage

Participants’ early desires for English were reinforced institutionally, resulting in strong interest and sometimes ‘love’ for the subject of English. At school, participants’ interest was mediated and intensified through interactions with curricula, pedagogies, teachers, teaching styles, and language policy, regardless of the medium of instruction. In school, they discovered new meanings associated with their develo** English skills. They were inspired to invest in learning English as they sought ‘to make a meaningful connection between [their] desire and commitment to learn [the] language, and their changing identity’ (Norton, 2010). Their desire for English constantly shifted across institutional practices and beyond, together with their emotional responses to these, as in a socially mediated process children learn interacting with others (van der Veer, 2012).

Participants held mixed feelings about learning English at school, particularly in relation to how the language was taught. Learning English was not always enjoyable. Jasha, who reflected that she only enjoyed it when speaking activities were included in the lessons, commented:

…it was quite boring: boring texts to read, boring lessons on grammar, no listening, and no speaking. And boring teaching! … the antiquated Prussian system …learning …supposed to be a hard job, not fun.

However, some participants enjoyed communicative and translanguaging elements of learning with their peers and teachers (see also Aoyama, 2020; Cenoz & Gorter, 2020). Negative feelings, such as of ‘rote learning’ shifted into positives when participants experienced democratic ways (Soong, 2018) of language learning, such as through play, music and singing, and their sense of achievement in English learning grew.

Participants recalled feelings of pride and positive emotions (e.g., Ross & Stracke, 2016) in their language learning progress and the social recognition which accompanied their develo** skills. As Jigna remembered, ‘my interest in English was reflected in my academic achievements which further encouraged me to embrace English in my educational choices’. Feelings of self-consciousness led high-achiever Carlos to feel embarrassed about achieving consistently strong marks in all assessment, to the extent that he began to deliberately make errors. However, this feeling of embarrassment had positive connotations for Carlos, and it drove him to feel empowered about his English skills. The sense of pride emanated from the energies of positive emotions through meaningful connection with pursuing language learning (Ross & Stracke, 2016).

Positive or negative relational experiences with teachers and the curricula also contributed substantially to the participants’ learning and future professional selves. Through lived experiences with different teachers, Jasha learnt how not to be unethical and partial in her teaching as well as how to develop an identity of English language and culture through her full immersion in her interaction with the teacher and the language. Jasha nostalgically reminisced,

When I was in Year 7, I think, I volunteered to accompany a teacher to a bookshop … The Picture of Dorian Gray. I asked her whether she could get an extra book for me, and she did. I consider this the beginning of MY English. This was the first time I realised that English could be alive and beautiful, that it can express feelings and send subtle messages. To this day I don’t dare to re-read The Picture of Dorian Gray in fear that the magic will disappear. The experience is too precious to lose, even today.

An ecstatic experience for child-Jasha, going to the bookshop with her teacher was an affective moment which was beyond her rationalisation. Many years later, the joy of reading and sensing English in the book was still precious for her.

Teachers and tutors were powerful sources of inspiration and reflection of English language teaching and learning experiences for most other participants too. Institutional practices created affective environments in which participants’ already embodied desires for English were reinforced through collectively produced affects. These embodied language learning experiences also reveal how participants’ everyday and scientific concepts acted dialectically (Vygotsky, 1987b)—for example, they could relate their everyday understandings of English (acquired through books and pop-culture) to the linguistic concepts taught in schools. The embodiment of desire and knowledge draws attention to educational institutions as assemblages that are situated in broader assemblages constituting the cultural-historical life of society. Now, we turn to cultural forces as assemblages.

Local and global forces as assemblages

All participants storied how their desires for English language and associated cultural forces were equally fostered by the influences of cultural-historical discourses and artefacts (Anning et al., 2008; Rogers et al., 2014; Somerville, 2011). Their desires were produced as collective affections at local and global levels. Multiple cultural-historical discourses (Turner & Lin, 2020), such as colonial history, English as a global language, and the prestige status and utility of the language generated affective intensity. For example, Jigna, who lived in post-colonial and multilingual India, narrated her relationship with English as complex and deeply rooted in her consciousness:

English comes naturally to me … It is and was the stamp of quality education … I was made aware of the archetypes of cultural-dom while trying to imbibe everything in English.

Mandy also believed that colonial histories had shaped the contemporary status of English in the Philippines. In the region, English is associated with job opportunities and income since their English-speaking workforces are employed by Business Process Outsourcings (BPOs), such as call centres. Global and neoliberal market forces are entangled with English (Pennycook, 2002, 2007) and encounter numerous other educational, ideological and linguistic forces. For example, in Vietnam, Quang reflected on the ideology of native-speakerism and the notion of authenticity in language use, to which he was not only exposed, but also in which he was also complicit:

At first, my professional self was formed by the collective view that Vietnamese teachers are inferior due to our lack of exposure to authentic English language materials and communities. I accepted that as fact and even played a role in downplaying our own values and elevating that of ‘native speakers’. While believing that the ‘native speakers’ could do a better job, I propagated the idea to my peers without questioning the validity of such claim.

Living in war zones, with trans-generational violence, may have strongly influenced Jasha and Raphael to divert their desires beyond their local contexts. Raphael, while undertaking compulsory military training and service, was eager to interact with English-speaking tourists. The profound emotions generated by these interactions brought feelings of rest and diversion. Their affect around learning English included ‘a terrain ranging from emotion, to feelings, desire, love, hate, anger, boredom, excitement, frustration, violence’ (Albrecht-Crane, 2002, p. 7).

The embodied socio-historical values of English drove the participants to embrace English learning further within complex flows of spatial–temporal and embodied relations. They conceptualised associated cultural tools (or skills in using English) as mediational and imaginative artefacts to mobilise across spaces (Marginson & Dang, 2017).

Higher education as assemblages

As adults, most participants became conscious of how their intellectual capacities could mediate their emotionally driven desires and that they could agentively drive their own actions and behaviours (Deleuze & Guattari, 1983; Spinoza, 1994, Vygotsky, 1930, 1982a as cited in Van der Veer, 1984). Perhaps their desires for English then coincided with those related to their emerging professional selves in the broader uses and practices of English and professional education. They most consciously opted to study English and related disciplines in universities. For example, similar to the influence over time of choosing the career in the study by Plunkett and Dyson (2011), Quang rationalised that he had chosen to study teaching English as a foreign language (TEFL) because he was aware of his abilities and skills in English. However, he acknowledged that his embodied desires, influenced by a significant other, were still a strong contributing factor in his career choice:

My choice was also influenced by an English teacher I had, who was caring and knowledgeable; she most certainly fit into our Vietnamese vision of a teacher: wise, strict but caring, dedicated, who gives but asks for little in return. I of course aspired to be such a teacher.

Akin to the teacher in the study by Gomez et al. (2007), Frida’s rationalisation of choosing teaching as a career through passing a “Licensure Exam for Teachers” emerged from her deep-seated experiences of English learning as a child in the extended family, community libraries, a neighbour’s library and the church in “Quezon City”. Her other emotional attachments to decide to be an ELT were her higher education through the medium of English and working as an international ship crew. In fact, she fortuitously discovered her decision to be a teacher when she enjoyed teaching English to a crew member on the cruise, a ‘60-year-old Colombian musician’:

… it felt good to help out this person. This was my first conscious effort at hel** someone learn survival English. When I returned to the Philippines after a few contracts abroad, I decided to get a job teaching English.

Within higher education, English became the medium through which to gain knowledge, be exposed to the world, become qualified for the teaching profession, and potentially migrate to English-speaking countries. Participants expanded their networks and opportunities, develo** their English proficiency further and eventually becoming English language teachers formally. Some participated in cultural activities in English in and out of educational institutions; for example, Natalie entered university debate competitions, Raphael communicated with English-speaking tourists, and Carlos immersed himself in ‘Cultural Inglesa’ (emphasis added).

As they became further exposed to different manifestations of the language, and their awareness of ideas around the language grew, some participants began to consider their English skills not yet advanced—or authentic—enough. In response, Becca and Jasha strove assiduously to learn what they called ‘real English’. In the pursuit of ‘real English’, Becca travelled across English speaking countries:

… my first contact with real communication in English occurred near Birmingham ... After that I spent another summer in New Jersey, USA when I was twenty-one … I think that the real break in my English studies came when I came to Australia.

Similarly, Jasha worked hard to bring her ‘English alive … and so I did work hard, mostly on the appropriateness of expressions, and intonation’. She believed ‘there was a real English somewhere out there, and it was my job to find it’. It is however not uncommon for non-native English speakers to have an ambivalent relationship with their so called ‘accented English’, as they might ‘want a NS English identity as expressed in a native-like accent’ (Jenkins, 2005, p. 541). This may be due to the historical and global impact of the discourse of native-speakerism, its adjacent discourses and its associated ideological values and meanings (Holliday, 2018; Nigar et al., 2023).

Desires through traits, values, attributes, and investments

Personal traits (Parsons, 1909) and values (Kassabgy et al., 2001) are argued to be major contributing factors in career decision-making across professional fields (Judge, 1994; Jugović et al., 2012). These work as the ‘cycle of influence’ (Manuel, 2003) as the study by Manuel and Hughes (2006) reports: ‘personal aspirations to work with young people to make a difference in their lives; to maintain a meaningful engagement with the subject area they were drawn to; and to attain personal fulfilment and meaning’ (p. 5). Across assemblages of desiring production, participants’ perceived attributes and interests played an important role. Frida told of her ‘innate and genuine sense of wanting to help others’. Frida added that she ‘would like to pass on what knowledge’ she had gained ‘through work/life experience’ by teaching English ‘to those who wanted to learn it as a second language’. Becca related her own painstaking language learning and international student experiences to what her students were going through. Carlos emphasised the importance of making a difference to his students on the basis that English education could be a form of individual empowerment. Similarly, Raphael recollected,

I enjoyed hel** people improve on their language … because I saw myself, still see myself as one of them, one of the migrants that have come here and found it hard. And if I made it, then I could help other people make it. So that was one of the motivations of becoming a teacher and hel** people.

The participants wanted to make a difference (Lovett, 2007) in others’ lives by making use of their skills and knowledge. Their knowledge of English, personal attributes, and professional values, in congruence with professional cultures, contributed to their career choices (Judge, 1994). They imagined empowerment through the process of empowering others.

Becoming and staying a teacher

Through various networking opportunities, 13 of the participants who started teaching in their countries of origin and some who taught in non-native English-speaking contexts found their first employment serendipitously, without difficulty. Amongst them are Thi through her friend ‘Phuong’, Mahati through her ‘father’s friend’, Oksana through her ‘teachers’, and the rest through formal application processes. Indeed, compared to the Australian context (e.g., Nigar et al., 2023), participants remembered their first employment experiences in their countries of origin as accomplishments. Studies in settings in the United States (Mahboob & Golden, 2013) and the United Kingdom (Clark & Paran, 2007) also suggest that non-native English teachers’ employment is challenged by the so-called native-speaker selection criterion.

They recalled these first positions as accomplishments and described their teaching experiences as developmental, rewarding and fulfilling. Mahati was ‘very well respected [as a teacher] in India and in Africa’. Similarly, Oksana reflected that ‘Everyone respected me for being an English teacher at the age of 21, so I stay in the profession’. Thi said that her first few days working as a teacher ‘changed my life forever as I felt energised working with young children and a mix of local and expatriate teachers every week’. Becca summarised:

I finally got to do something that I actually enjoy and I’m very grateful for it. Every day when I step into the classroom, I think to myself how fortunate I am to be doing something that most of the time feels more like a hobby than a job.

All participants eventually migrated to Australia and obtained ELT positions there. Different lines of ‘desired becoming’ were at play: through migration, participants desired to improve their English, undertake further studies, or teach English to others. The accumulation of the ‘affectives’, in both unconscious desires and preconscious social investments, energised them to act and become mobile.

Finding employment as an ELT was not without its challenges. For example, Quang had completed a relevant undergraduate degree in Vietnam and two post-graduate degrees in Australia, but still it took him until the second year of his second post-graduate degree to get a paid teaching job. Becca, while an international student for seven years in Sydney, had ‘been kind of dreaming of, for the previous three or four years, doing a master of TESOL’. Ling Ling came to Adelaide as a high school student and moved to Melbourne to complete ‘a secondary education and arts degree, majoring in Japanese, Chinese and English translation’. However, despite the challenging landscape of securing employment, they were still positive about develo** their English and ardently pursued their careers.

Participants’ decisions to remain in teaching also involved negotiations with challenges within their educational institutions. The commodification of English and prevalent native-speakerism appeared in a few teachers’ stories. Thi commented that, in the Vietnamese English teaching context, ‘the preference of native speakerism is still vastly dominant, which has a profound negative impact on the non-native teacher’s self-confidence and self-esteem’. Mandy was upset when ‘native English speakers (without any legitimate qualifications)’ were paid three times more than she was at her institution in the Philippines. While completing an MA TESOL in Sydney, Becca said,

…from the very first class of my master’s degree course, I was terrified of having to teach English to an actual group of real humans … It was all about me and my own grasp of English. Is my English good enough to teach it to others? Am I qualified enough to teach it to others? What if the students see right through my feelings of inadequacy? What if they catch me off guard and I won’t be able to answer their questions?

The findings above reveal that decisions to become ELTs for the 16 participants did not occur in teleological order or determinate ways. They transpired in ceaseless ideas of spatiotemporal assemblages of becoming users and teachers of English. Participants’ bodies were affectively invested as the intricate interactions of minutely assembled (Braidotti, 1993) socio-cultural and symbolic drives across the lines of becoming.

Discussion

The participants’ decisions to become English language teachers were the products of ongoing interplays of socio-material desires related to learning English and becoming ELTs since early childhood. Their unconscious desires and preconscious social investments over time led them to rationalise their lines of becoming. Although the English language ‘desiring machine’ (Deleuze & Guattari, 1983) functions somewhat differently in and across non-English speaking countries, the flows of desire it produced for the participants were connected to the ‘social machine’ of English language education. We argue that, in part, this connection can be understood as an intersection of a desire to gain power through learning English and a desire to empower others.

Since early childhood, the participants’ desires were produced repeatedly across molar lines of disjunctions and segments. In family assemblages of produced desires, they were exposed to English popular culture and English learning activities, and they discovered they were desiring the desires held by others. Their fascination with books, music, television programmes and movies implicate the symbolic simulated significations (simulacra) of the consumer cultures of capitalist society (Baudrillard, 1994, 2016). The strategy of a captivating educational relationship (Sæverot, 2011) was evident when, at the age of four, Frida was given children’s books and nursery rhymes with pictures, was home-tutored in English by her grandmother and aunt, and was rewarded with her favourite treat when she wrote or counted in English. Frida’s desire was purposefully ignited ‘in the world of signs expressed in a pictorial language—an impact perception of a child prior to the language acquisition’ (Semetsky, 1999, pp. 67–68).

Despite the seductive mechanisms of molar lines, most of the participants sensed molecular lines of desire operational in affective ‘self-mastery’. Molecular lines take their own directions, which may or may not culminate in change. Participants started to connect to the pleasures and serendipities of learning English, exploring the novelty of the culture they associated with it. As Jasha put it: ‘then I discovered the joy of Agatha Christie, followed by G.K. Chesterton—so many opportunities to see different layers and different contexts of English! And different registers!’. The power of desire, a productive force, affected Jasha in the perpetuation of an active flow of elation in encounters with those books. Others were affected and enthused in engagements with books, movies, comics, serials, and games.

Participants’ desires were coded in the school system too, a molar line of coding and encoding production, reproduction, and simulation. According to Deleuze and Guattari (1988, pp. 75–76), ‘the compulsory education machine […] imposes upon the child semiotic coordinates … Language is made not to be believed but to be obeyed, and to compel obedience’. Most participants’ desires were stratified and segmented within capillaries of the education system (Savat & Thompson, 2015): ‘techniques and practices, as an expression of control society, constitute the new sorts of machines that frame and inhabit our educational institutions’ (p. 273). Notwithstanding the major molarisation of the institution, miniscule pleasures associated with learning English were experienced as they engaged intimately with special language programmes, resources, teachers, and achievements. For example, Jasha and Janaki’s teachers had sparked a love of reading which would carry into the future. Sensations of care and secret bliss were evident when Jasha’s teacher purchased her a much-loved book. According to Sellar (2015, p. 426), this may be described as ‘discovering the desiring-machines operating outside of representation and reaching the investment of unconscious desire in the social field’.

Participants felt empowered, taking pride in their develo** English language and cultural skills by engaging with the resources and other opportunities they could avail. Hien, Natalie and Jigna were proud of their English skills and academic achievements from childhood since they stood amongst others. The flows became materialised in the cases of inmost locus of self-management, private self-talk (Flanagan & Symonds, 2022) and enjoyable interactions with others and objects external to them. The encounters of ‘“affect” address those resonances in their bodies and their relations to each other that conjured non-representational kinds of effects—intensities, sounds, sensations, odours, touches, remembrances’ (Albrecht-Crane, 2002, p. 7).

Some participants were subjectified in the intricate and discrete ‘white walls’ of post-colonial and neoliberal ‘faciality’ of English. Globally, English is used in association with economic, ideological, socio-political and cultural forces (Shin, 2006). As discussed, native-speakerism and the notion of authentic language persist. Becca and Jigna pushed themselves to seek the real English at home and abroad. However, native-speakerism is divisive, and ‘the “native speaker” ideal plays a wide-spread and complex iconic role outside as well as inside the English-speaking West’ (Holliday, 2006, p. 385). However, along molecular lines, participants ‘not only have to deal with erosions of frontiers but with the explosions within shanty towns or ghettos’ (Deleuze, 1992, p. 5). They de-territorialised and kept seeking individual and intersubjective effectuations of molecular desire lines in multiplicities. For Jigna in India, ‘English became the language’ of her ‘thoughts and logic’; she viewed the multicultural and multilingual context in which she found herself through the lens of translanguaging in productive tension and desire (Turner & Lin, 2020).

Growing up, teacher participants broadened the imagined communities of English language and culture (Pavlenko & Norton, 2007), which influenced their choice of English teaching as a career. For Mahati and Janaki, commitment to English language learning was a means of emancipation from patriarchal norms (Kobayashi, 2002; McMahill, 1997), so they persisted in infiltrating the imagined communities of their ‘desired becomings’ (Norton, 2000). Through cyclicities of molecularities, driven by the axiomatic values of the participants as ‘“i-for-myself”, “i-for-the-other”, and “the-other-for-me”‘ (Pape, 2016, p. 279), the teachers imagined their selves in students’ selves, and in modulation, students’ selves in themselves. They desired their students to engage, experiment and connect (Mercieca, 2012).

Desire is always progressive since it is invested in social actions (Smith, 2011). Becca, Ling Ling, Quang and Raphael—as international students and immigrants—suffered as vulnerable workers (Colic-Peisker, 2011; Nyland et al., 2009); however, in ‘movements and rests’, they passionately pursued higher education and further training, and took pride in their academic achievements. They experienced culture shock and nostalgia, and they suffered emotionally. However, instead of collapsing into the ‘black hole’ (Deleuze & Guattari, 1983), they developed adaptability in affective multiplicities. They developed and transformed educationally, professionally, interpersonally and interculturally. For example, Becca dedicated every opportunity to develop her English to ‘the next level and be fluent’. After commencing teaching, she built kindred relationships with students, engaged with creative pedagogies, and was even learning Spanish as she felt it would benefit her many students who were proficient in the language.

Conclusion

Deleuze and Parnet (2007) define a profession as a ‘rigid segment, but also what happens beneath it, the connections, the attractions and repulsions which do not coincide with the segments, the forms of madness which are secret, but which nevertheless relate to the public authorities’ (p. 125). The participants of this study were situated in striated educational policies and regulations, teaching standards and curricula, professionalism and hierarchies. They also described their desires at the site of affective interactions, at the cut lines, which were stirring, multiple, connective, incidental, approving and revitalising over time.

Their career choices to teach English language were rationalised neither as ‘one stop’ events nor in linear processes of motivations; rather, these decisions were impacted by complex circuitous interchanges between personal and socio-cultural elements. Their narratives suggest that their processes of becoming English teachers were driven by the force of desire that materialised in interactions of the sensuous and the rational, in their thoughts of themselves and others, as they pondered, enquired, engaged, and connected to find their own-other-selves in others. Empowered and transfigured by affects (Spinoza, 1994), individuals’ lives pass on; as the operations of other bodies are inextricably conjoined with their own, so bodies realise themselves in relation to their own parts (Leibniz, 1898).

Itermingled in the spatiotemporal processes of becoming teachers were relational intimacies and multiplicities—esprit de corps and their rotations (Deleuze, 2001), and their effectual impacts to be empowered and empower others.

A world already envelops an infinite system of singularities selected through convergence … however, individuals are constituted which select and envelop a finite number of the singularities that their own body incarnates. They spread them out over their own ordinary lines, and are even capable of forming them again on the membranes which bring the inside and the outside in contact with each other. (Deleuze, 2004, p. 109)

We conclude that the concept of English teachers’ ‘desired becoming’ provides an aperture into the formation of their professional identities as an interplay of the affective and the rational. We invite all to embrace and appreciate that the combined role of the affective and the rational in teachers’ becoming is important to consider in future research in this area as well as for teacher recruitment and retention, hence potentially addressing critical teacher shortages. Exploring ‘affect and desire’ can illuminate not only the process of teacher recruitment and retention but also the decision to leave the profession, as well as overall job satisfaction. Including affective components in teacher education may have ‘an expansive power of ontological freedom’ and meaningful professional contribution (Kostogriz, 2012, p. 397), that may also address professional interests and resilience. This implies that choosing teaching as a career should be conceived with recognition of the primacy of affective experiences, counteracting solely rationalised discourses of professional regulation and accountability: ‘rationalization and control that produce a number of social pathologies, such as alienated teaching and learning and reified social relations between teachers and students’ (Kostogriz, 2012, p. 397). Future studies of desired becoming across different subject areas and settings of teaching might highlight the importance of affect in the work of teachers.

Data availability

Raw data were generated at the Faculty of Education, Monash University, Australia. Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author Nashid Nigar on request.

References

Albrecht-Crane, C. (2002). Affect matters: Agency and desire in pedagogy (3019156) [Doctoral Dissertation, Michigan Technological University]. Proquest.

Anning, A., Cullen, J., & Fleer, M. (2008). Early childhood education: Society and culture. Sage.

Aoyama, R. (2020). Exploring Japanese high school students’ L1 use in translanguaging in the communicative EFL classroom. Tesl-Ej, 23(4), n4.

Baudrillard, J. (1994). Simulacra and simulation. University of Michigan press.

Baudrillard, J. (2016). The consumer society: Myths and structures. Sage.

Braidotti, R. (1993). Discontinuous becomings: Deleuze on the becoming-woman of philosophy. Journal of the British Society for Phenomenology, 24(1), 44–55.

Bruinsma, M., & Jansen, E. P. (2010). Is the motivation to become a teacher related to pre-service teachers’ intentions to remain in the profession? European Journal of Teacher Education, 33(2), 185–200.

Bruner, J. S. (1990). Acts of meaning. Harvard University Press.

Caires, S., Almeida, L., & Vieira, D. (2012). Becoming a teacher: Student teachers’ experiences and perceptions about teaching practice. European Journal of Teacher Education, 35(2), 163–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2011.643395

Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2020). Teaching English through pedagogical translanguaging. World Englishes, 39(2), 300–311.

Chong, S., & Low, E.-L. (2009). Why I want to teach and how I feel about teaching—formation of teacher identity from pre-service to the beginning teacher phase. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 8(1), 51–72.

Clark, E., & Paran, A. (2007). The employability of non-native-speaker teachers of EFL: A UK survey. System, 35(4), 407–430.

Colic-Peisker, V. (2011). ‘Ethnics’ and ‘Anglos’ in the labour force: Advancing Australia fair? Journal of Intercultural Studies, 32(6), 637–654.

Cross, M., & Ndofirepi, E. (2015). On becoming and remaining a teacher: Rethinking strategies for develo** teacher professional identity in South Africa. Research Papers in Education, 30(1), 95–113.

Deleuze, G. (1992). Postscript on the societies of control. October, 59, 3–7.

Deleuze, G. (1994). Difference and repetition. Columbia University Press.

Deleuze, G. (2001). Pure immanence: Essays on a life. Zone Books.

Deleuze, G. (2004). Logic of sense. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1983). Anti-oedipus: Schizophrenia and capitalism. University of Minnesota.

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1988). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. Continuum.

Deleuze, G., & Parnet, C. (2007). Dialogues II. Columbia University Press.

Du Toit, C. W. (2014). Emotion and the affective turn: Towards an integration of cognition and affect in real life experience. HTS Theological Studies, 70(1), 01–09.

Flanagan, R. M., & Symonds, J. E. (2022). Children’s self-talk in naturalistic classroom settings in middle childhood: A systematic literature review. Educational Research Review, 35, 100432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2022.100432

Fleer, M. (2016). An everyday and theoretical reading of “Perezhivanie” for informing research in early childhood education. International Research in Early Childhood Education, 7(1), 34–49.

Fleer, M. (2021). Conceptual playworlds: The role of imagination in play and learning. Early Years, 41(4), 353–364.

Fleer, M., González Rey, F., & Veresov, N. (2017). Perezhivanie, emotions and subjectivity. Springer.

Foucault, M. (1980). Power/knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings, 1972–1977. Harvester Press.

Foucault, M. (2013). Archaeology of knowledge. Routledge.

Fox, N. J., & Alldred, P. (2015). New materialist social inquiry: Designs, methods and the research-assemblage. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 18(4), 399–414.

Gomez, M. L., Black, R. W., & Allen, A.-R. (2007). “Becoming” a teacher. Teachers College Recor, 109(9), 2107–2135. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146810710900901

Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1994). Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 105–117). Sage.

Hargreaves, A. (2005). The emotions of teaching and educational change. In A. Hargreaves (Ed.), Extending educational change (pp. 278–290). Springer.

Heinz, M. (2011). The next generation of teachers: Selection, backgrounds and motivations of second-level student teachers in the Republic of Ireland [Doctoral dissertation, National University of Ireland]. Publisher.

Heinz, M. (2013). Why choose teaching in the republic of Ireland?–student teachers’ motivations and perceptions of teaching as a career and their evaluations of Irish second-level education’. European Journal of Educational Studies, 5(1), 1–17.

Heinz, M. (2015). Why choose teaching? An international review of empirical studies exploring student teachers’ career motivations and levels of commitment to teaching. Educational Research and Evaluation, 21(3), 258–297.

Holliday, A. (2006). Native-speakerism. ELT Journal, 60(4), 385–387.

Holliday, A. (2018). Native Speakersim. In J. I. Liontas (Ed.), The TESOL encyclopedia of English language teaching (pp. 1–7). Wiley-Blackwel. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118784235.eelt0027

Jenkins, J. (2005). Implementing an international approach to English pronunciation: The role of teacher attitudes and identity. TESOL Quarterly, 39(3), 535–543.

Judge, T. A. (1994). Person–organization fit and the theory of work adjustment: Implications for satisfaction, tenure, and career success. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 44(1), 32–54.

Jugović, I., Marušić, I., Pavin Ivanec, T., & Vizek Vidović, V. (2012). Motivation and personality of preservice teachers in Croatia. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 40(3), 271–287.

Jungert, T., Alm, F., & Thornberg, R. (2014). Motives for becoming a teacher and their relations to academic engagement and dropout among student teachers. Journal of Education for Teaching, 40(2), 173–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2013.869971

Kassabgy, O., Boraie, D., & Schmidt, R. (2001). Values, rewards, and job satisfaction in ESL/EFL. Motivation and Second Language Acquisition, 4(2), 213–237.

Kelchtermans, G., & Deketelaere, A. (2016). The emotional dimension in becoming a teacher. In J. Loughran & M. Hamilton (Eds.), International handbook of teacher education (pp. 429–461). Springe.

Klassen, R. M., Al-Dhafri, S., Hannok, W., & Betts, S. M. (2011). Investigating pre-service teacher motivation across cultures using the Teachers’ ten statements test. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(3), 579–588.

Kobayashi, Y. (2002). The role of gender in foreign language learning attitudes: Japanese female students’ attitudes towards English learning. Gender and Education, 14(2), 181–197.

Kostogriz, A. (2005). Dialogical imagination of (inter) cultural spaces: Rethinking the semiotic ecology of second language and literacy learning. In J. K. Hall, G. Vitanova, & L. Marchenkova (Eds.), Dialogue with Bakhtin on second and foreign language learning: New perspectives (pp. 189–210). Publisher.

Kostogriz, A. (2012). Accountability and the affective labour of teachers: A Marxist-Vygotskian perspective. The Australian Educational Researcher, 39(4), 397–412.

Kövecses, Z. (2004). Emotion, metaphor and narrative. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8(4), 154–156.

Lai, K.-C., Chan, K.-W., Ko, K.-W., & So, K.-S. (2005). Teaching as a career: A perspective from Hong Kong senior secondary students. Journal of Education for Teaching, 31(3), 153–168.

Lam, B. H. (2012). Why do they want to become teachers? A study on prospective teachers’ motivation to teach in Hong Kong. Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 21(2), 307–314.

Leibniz, G. W. (1898). Monadology and other philosophical essays. In R. Latta (Ed.), Philosophical papers and letters (pp. 643–653). Oxford University Press.

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (1994). Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 45(1), 79–122.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2004). What should we do about motivation theory? Six recommendations for the twenty-first century. Academy of Management Review, 29(3), 388–403.

Lovett, S. (2007). “Teachers of promise”: Is teaching their first career choice? New Zealand Annual Review of Education., 16, 29–53.

Mahboob, A., & Golden, R. (2013). Looking for native speakers of English: Discrimination in English language teaching job advertisements. Voices in Asia Journal, 1(1), 72–81.

Manuel, J. (2003). ‘Such are the ambitions of youth’: Exploring issues of retention and attrition of early career teachers in New South Wales. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 31(2), 139–151.

Manuel, J., & Hughes, J. (2006). ‘It has always been my dream’: Exploring pre-service teachers’ motivations for choosing to teach. Teacher Development, 10(1), 5–24.

Marginson, S., & Dang, T. K. A. (2017). Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory in the context of globalization. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 37(1), 116–129.

McMahill, C. (1997). Communities of resistance: A case study of two feminist English classes in Japan. TESOL Quarterly, 31(3), 612–622.

Mercieca, D. (2012). Becoming-teachers: Desiring students. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 44(sup1), 43–56.

Michell, M. (2016). Finding the" Prism": Understanding Vygotsky’s" Perezhivanie" as an Ontogenetic Unit of Child Consciousness. International Research in Early Childhood Education, 7(1), 5–33.

Nguyen, M. H., & Ngo, X. M. (2023). An activity theory perspective on Vietnamese preservice English teachers’ identity construction in relation to tensions, emotion and agency. Language Teaching Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688221151046

Nietzsche, F. (2002). Nietzsche: Beyond good and evil: Prelude to a philosophy of the future. Cambridge University Press.

Nietzsche, F. (2008). Thus spoke Zarathustra: A book for everyone and nobody. Oxford University Press.

Nigar, N. (2019). Hermeneutic phenomenological narrative enquiry: A qualitative study design. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 10(1), 10–18.

Nigar, N., Kostogriz, A., Gruney, L., & Janfada, M. (2023). “No one would give me that job in Australia”: When professional identities intersect with how teachers look, speak and where they come from. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 44(5), 1–18.

Norton, B. (2000). Identity and language learning: Gender, ethnicity and educational change. Longman.

Norton, B. (2010). Language and identity. In N. H. Honrberger & S. L. McKay (Eds.), Sociolinguistics and language education (pp. 349–369). Multilingual Matters.

Nyland, C., Forbes-Mewett, H., Marginson, S., Ramia, G., Sawir, E., & Smith, S. (2009). International student-workers in Australia: A new vulnerable workforce. Journal of Education and Work, 22(1), 1–14.

Olive, J. L. (2014). Reflecting on the tensions between emic and etic perspectives in life history research: Lessons learned. Forum: Qualitative Social Research. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-15.2.2072

Oplatka, I. (2009). Emotion management and display in teaching: Some ethical and moral considerations in the era of marketization and commercialization. In P. Schutz & M. Zembylas (Eds.), Advances in teacher emotion research (pp. 55–71). Springer.

Pape, C. (2016). Husserl, Bakhtin, and the other I. or: Mikhail M. Bakhtin–a Husserlian? Horizon. Фeнoмeнoлoгичecкиe иccлeдoвaния, 5(2), 271–289. https://doi.org/10.18199/2226-5260-2016-5-2-271-289

Parsons, F. (1909). Choosing a vocation. Houghton Mifflin.

Pavlenko, A., & Norton, B. (2007). Imagined communities, identity, and English language learning. In J. Cummins & C. Davison (Eds.), International handbook of English language teaching (pp. 669–680). Springer.

Pennycook, A. (2002). English and the discourses of colonialism. Routledge.

Pennycook, A. (2007). ELT and colonialism. In J. Cummins & C. Davison (Eds.), International handbook of English language teaching (pp. 13–24). Springer.

Plunkett, M., & Dyson, M. (2011). Becoming a teacher and staying one: Examining the complex ecologies associated with educating and retaining new teachers in rural Australia. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 36(1), 32–47.

Richardson, P., & Watt, H. (2006). Who chooses teaching and why? Profiling characteristics and motivations across three Australian universities. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 34(1), 27–56.

Rieber, R., & Aaron, C. (1987). Thought and word. In R. R. A. Carton (Ed.), The collected works of L. S. Vygotsky. Plenum Publishers.

Rogers, M., Rowan, L., & Walker, R. (2014). Becoming Ryan: Lines of flight from majoritarian understandings of masculinity through a high school reading and mentoring program. A story of possibility. The Australian Educational Researcher, 41, 541–563.

Ross, A. S., & Stracke, E. (2016). Learner perceptions and experiences of pride in second language education. Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, 39(3), 272–291.

Sæverot, H. (2011). Kierkegaard, seduction, and existential education. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 30(6), 557–572.

Savat, D., & Thompson, G. (2015). Education and the relation to the outside: A little real reality. Deleuze Studies, 9(3), 273–300.

Sellar, S. (2015). A strange craving to be motivated: Schizoanalysis, human capital and education. Deleuze Studies, 9(3), 424–436.

Semetsky, I. (1999). The adventures of a postmodern fool, or the semiotics of learning. In S. Simpkins, C. W. Spinks, & J. Deely (Eds.), Semiotics 1999 (pp. 477–495). Peter Lang Publishing.

Sévérac, P. (2017). Consciousness and affectivity: Spinoza and Vygotsky. Stasis. https://doi.org/10.33280/2310-3817-2017-5-2-80-109

Shin, H. (2006). Rethinking TESOL from a SOL’s perspective: Indigenous epistemology and decolonizing praxis in TESOL. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 3(2–3), 147–167.

Simonsz, H., Leeman, Y., & Veugelers, W. (2023). Beginning student teachers’ motivations for becoming teachers and their educational ideals. Journal of Education for Teaching: JET, 49(2), 207–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2022.2061841

Smith, D. W. (2011). Deleuze and the question of desire: Towards an immanent theory of ethics. In N. June (Ed.), Deleuze and ethics (pp. 123–141). Edinburgh University Press.

Somerville, M. A. (2011). Becoming-frog: Learning place in primary school. In M. A. Somerville, B. Davies, K. Power, S. Gannon, & P. de Carteret (Eds.), Place pedagogy change (pp. 65–80). Sense Publishers.

Song, J. (2016). Emotions and language teacher identity: Conflicts, vulnerability, and transformation. TESOL Quarterly, 50(3), 631–654.

Soong, H. (2018). Transnational teachers in Australian schools: Implications for democratic education. Global Studies of Childhood, 8(4), 404–414.

Spinoza, B. (1994). A Spinoza reader: The Ethics and other works. Princeton University Press.

Struyven, K., Jacobs, K., & Dochy, F. (2013). Why do they want to teach? The multiple reasons of different groups of students for undertaking teacher education. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 28(3), 1007–1022.

Thornberg, R., Wänström, L., Lindqvist, H., Weurlander, M., & Wernerson, A. (2023). Motives for becoming a teacher, co** strategies and teacher efficacy among Swedish student teachers. European Journal of Teacher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2023.2175665

Trent, J. (2012). Becoming a teacher: The identity construction experiences of beginning English language teachers in Hong Kong. The Australian Educational Researcher, 39, 363–383.

Turner, M., & Lin, A. M. (2020). Translanguaging and named languages: Productive tension and desire. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 23(4), 423–433.

van der Veer, R. (1984). Early periods in the work of LS Vygotsky: The influence of Spinoza. Learning and teaching on a scientific basis: Methodological and epistemological aspects of the activity theory of learning and teaching. Psykologisk Institut.

van der Veer, R. (2012). Cultural-historical psychology: Contributions of Lev Vygotsky. In J. Valsiner (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of culture and psychology (pp. 58–68). Oxford University Press.

van Manen, M. (1990). Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. The Althouse Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Interaction between learning and development. Readings on the Development of Children, 23(3), 34–41.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1987). Thinking and speech. In R. W. Rieber & A. S. Carton (Eds.), The collected works of LS Vygotsky, Problems of general psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 39–285). Plenum Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1999). The teaching about emotions: Historical psychological studies/on the problem of the psychology of the actor’s creative work. In R. W. Rieber & A. S. Carton (Eds.), The collected works of Vygotsky (pp. 71–235). Plenum.

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Expectancy–value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 68–81.

Wolf, A. G., Auerswald, S., Seinsche, A., Saul, I., & Klocke, H. (2021). German student teachers’ decision process of becoming a teacher: The relationship among career exploration and decision-making self-efficacy, teacher motivation and early field experience. Teaching and Teacher Education, 105, 103350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103350

Yüce, K., Şahin, E. Y., Koçer, Ö., & Kana, F. (2013). Motivations for choosing teaching as a career: A perspective of pre-service teachers from a Turkish context. Asia Pacific Education Review, 14(3), 295–306.

Zembylas, M. (2006). Teaching with emotion: A postmodern enactment. Information Age Publishiing.

Zembylas, M. (2015). Emotion and traumatic conflict: Reclaiming healing in education. Oxford University Press.

Zembylas, M. (2021). Affect and the rise of right-wing populism: Pedagogies for the renewal of democratic education. Cambridge University Press.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. This article is a part of a thesis at the Faculty of Education, Monash University, Australia. No external funding was received for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Nashid Nigar: 65 percent. AK: 20 percent. LG: 15 percent.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

There is no competing interest of a financial or personal nature involved in this research.

Ethical Approval

The research (project ID 19107) was approved regarding ethical measures by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee. Prior to signing the consent forms, all participants were informed of the voluntary nature of the research participation and their full anonymity.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nigar, N., Kostogriz, A. & Gurney, L. Becoming an English language teacher over lines of desire: Stories of lived experiences. Aust. Educ. Res. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-023-00662-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-023-00662-4