Abstract

Climate change, overfishing, and other anthropogenic drivers are forcing marine resource users and decision makers to adapt—often rapidly. In this article we introduce the concept of pathways to rapid adaptation to crisis events to bring attention to the double-edged role that institutions play in simultaneously enabling and constraining swift responses to emerging crises. To develop this concept, we draw on empirical evidence from a case study of the iconic Maine lobster (Homarus americanus) industry. In the Gulf of Maine, the availability of Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus) stock, a key source of bait in the Maine lobster industry, declined sharply. We investigate the patterns of bait use in the fishery over an 18-year period (2002–2019) and how the lobster industry was able to abruptly adapt to the decline of locally-sourced herring in 2019 that came to be called the bait crisis. We found that adaptation strategies to the crisis were diverse, largely uncoordinated, and imperfectly aligned, but ultimately led to a system-level shift towards a more diverse and globalized bait supply. This shift was enabled by existing institutions and hastened an evolution in the bait system that was already underway, as opposed to leading to system transformation. We suggest that further attention to raceways may be useful in understanding how and, in particular, why marine resource users and coastal communities adapt in particular ways in the face of shocks and crises.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adaptation, agency, and institutions

Coastal communities around the world are experiencing major environmental and socioeconomic changes that are affecting the productivity of marine ecosystems and the ability for marine resource users to sustain their livelihoods. These changes are being driven by a wide range of factors including sea level rise and climate change (Barnett and Adger 2003; Nye et al. 2009; Raitsos et al. 2010), declining fish stocks (Worm et al. 2006), shifting coastal demographics (Colburn and Jepson 2012), competition for ocean space (Bennett et al. 2015), and investments in the blue economy (Silver et al. 2015; Campbell et al. 2021). Changes are particularly pronounced in places like the Gulf of Maine, where ocean conditions are changing at unprecedented rates and affecting commercially important species like the American lobster (Homarus americanus) (Pershing et al. 2015).

The pace and magnitude of socioeconomic and environmental change raises important questions about how and to what extent marine resource users will be able to adapt to future shocks and crises (IPCC 2018). These questions are particularly salient to discussions about the resilience of ocean-dependent communities—and the people within them—since the frequency of shocks in fisheries and food systems is rising with increased global connectivity (Cottrell et al. 2019; Kummu et al. 2020).

The extent to which marine resource users are able to withstand shocks is generally seen as a function of the magnitude of the impact on the system and the extent to which adaptation occurs (Walker et al. 2004; Smit and Wandel 2006; Marshall et al. 2013). While adaptation can be a passive process (Smit et al. 2000), scholars generally recognize the active role that people and entities play in bringing about change (Adger 2005; Folke et al. 2010; McLaughlin 2011). The capacity to influence change is referred to as agency (Giddens 1979; McLaughlin and Dietz 2008) and comes from a range of factors, including being able to articulate compelling visions of the future and having the ability to mobilize the social, cultural, economic, political, and ecological resources and relationships necessary to garner change (Lawrence and Phillips 2004; Maguire et al. 2004; Garud et al. 2007; Lounsbury and Crumley 2007; Welter and Smallbone, 2011; Stoll 2017).

For decades, neo-institutional scholars have vigorously debated the relationship between agency and the institutions within which people are situated (DiMaggio 1998). At the root of this debate is a question about the role that institutions, defined broadly as the established norms, rules, and practices as well as sociocultural and environmental contexts, play in constraining individual and collective behavior (Ostrom 1990; North 1990; Prell et al. 2010). Part of the challenge is that institutions are “sticky” and interfere with rational choice behavior (McCay 2002), thereby creating barriers to adaptation and change (Alexander 2001).

Work by Holm et al. (2020) on the co-production of knowledge in the Norwegian cod fishery is illustrative of the constraining nature of institutions. Of particular salience here is their description of how their effort to transform the fisheries science process in Norway failed because scientists and fishers alike could not escape their conventional roles in the science-making process. As a result, the collaborators ultimately replicated the scientist-industry dynamic that they had sought to change. The history of the licensing system for commercial fisheries and aquaculture in Maine, USA similarly points to the stickiness of institutions and the challenge they pose in bringing about transformative shifts. For the last several decades, policymakers have routinely changed the licensing system to address specific problems in specific fisheries (Stoll et al. 2016). These efforts were meant to support the fishing sector; however, an unintended consequence of these legislative changes was that they contributed to the overall decline in the number of fisheries that fishers were participating in. While this loss of livelihood diversification has been identified as a source of vulnerability, fishers, shoreside businesses, and even fishery managers and scientists simultaneously became invested in the emergent licensing system, thereby making them resistant to legislative proposals associated with comprehensive licensing reform.

The influence that institutions have on individual and collective agency creates what Torfing (2001, p. 290) describes as a “‘logical impossibility’ of a total dislocation.” In other words, there is a path dependency between current and future systems such that emergent strategies and approaches are often shaped by those that preceded them (North 1990; Mosse 1997; Pierson 2000; Kay 2005; Cote and Nightingale 2012). Path dependency does not mean that system change is entirely deterministic, but it brings forward the idea that institutions—like ruts in a road—often guide behavior even if that behavior is not the most suitable course of action (Torfing 2001).

The tension between actors’ agency and the inertia created by institutions as well as the related idea that institutions create path dependencies are both germane to crisis adaptation. Indeed, crises often necessitate rapid and large-scale responses, while at the same time institutions can be expected to limit the range of practicable solutions that can be acted upon. We can therefore hypothesize that in periods of real or perceived crisis—when there is acute pressure to act—paths with the least institutional inertia will become the focus of adaptation activities. In these instances, crises have the potential to propel systems along pathways they are already moving, rather than putting them on new and transformative trajectories altogether. In this paper, we refer to the pathways that emerge in response to Rapid Adaptation to Crisis Events as “raceways” in reference to the path dependencies created by existing institutions and the double-edged role these institutions play in simultaneously facilitating and constraining rapid adaptation (Fig. 1).

Conceptual framework the pathway to rapid adaptation to crisis events (“raceway”) concept following a system shock, where T0 is time before a shock, Ts is time at the point of shock, and TR is time at some point of recovery. From left to right: A system is progressing along a particular path that is supported by formal and informal institutions, until it is disrupted by a shock. The shock necessitates rapid system change (SC). Inertia (I) created by existing institutions constrains the system from moving in a new direction (transformation), but facilitates rapid change in a direction the system is already moving (acceleration)

Our aim in develo** the concept of “raceways” is to contribute to the adaptation literature by focusing on how resource-dependent systems adapt in the face of crisis with a particular emphasis on the role existing institutions play in the process. We develop the concept of raceways by focusing specifically on the iconic lobster industry in the Gulf of Maine in the Northwest Atlantic and how the industry adapted to a major reduction in the availability of locally sourced Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus), which was historically the predominant source of bait. We begin by situating the bait crisis within the broader context of the lobster industry, which has become increasingly dependent on global trade to market lobster. We then show how bait use has changed over the last 16 years and describe the adaptation strategies that the lobster industry deployed during a recent bait crisis.

Rapid adaptation to the bait crisis in the lobster industry

American lobster is the most valuable commercial fishery in the United States (NOAA 2018). Approximately 80% of lobster landings occur in the state of Maine (ASMFC 2019). Over the past 50 years, annual lobster landings in Maine have increased significantly, growing from 7500 to over 45 000 mt. Since 2011, the ex-vessel value has been between $335 and $540 million ($USD) (ME DMR 2019). As the lobster fishery has grown, so too has the geographic reach of the lobster market. In 2019, lobster landed in the United States was traded to more than 80 countries worldwide at an estimated value of $605 million (United Nations 2021). By comparison, the United States traded $254 million worth ($367 million adjusted for inflation) of lobster to just over 50 countries in 2001 (United Nations 2021). In recent years, markets in Asian have become particularly important, surpassing Europe as the second most important trade region outside North AmericaFootnote 1 (Stoll et al. 2018). These markets have been established through private and public investment in marketing, infrastructure, and technology, including state sponsored trade missions and grant funding to support domestic processing and storage facilities.

Despite the storied success of the fishery, the lobster industry faces multiple socioeconomic and environmental challenges. For example, as international trade of lobster has increased, the fishery has become susceptible to trade-related shocks caused by geopolitical disputes, recessions, and disruptions to processing and transportation (Stoll et al. 2018). In recent years, the fishery has also faced the decline of Atlantic herring, a small, pelagic species of fish that has been an important bait used in the lobster fishery.

For much of the last two decades, approximately 100 000 mt of herring was harvested from the Gulf of Maine per year (ASMFC 2019). As recently as the early 2000s, an estimated 70 to 75% of this catch was used in the lobster industry as bait, equal to 70 to 90% of the total bait needed to support the fishery (Saila et al., 2002; Grabowski et al. 2010) (also see Driscoll et al. 2015). Most of this catch is delivered to lobster fishers via local networks of bait dealers in New England (Stoll et al. 2015). Fishers place this bait inside a compartment in their traps called the “kitchen” to attract lobsters. Baited traps are then left to fish for several days before being checked and re-baited. Fishers are required to purchase a trap tag each year for every lobster trap they will deploy that year. With some exceptions, fishers who are entering into the fishery are allowed to purchase 150 trap tags in their first year and then can purchase an additional 100 trap tags each subsequent year until they reach a total of 800 trap tags. In 2018, fishers purchased a total of 2.8 million trap tags. While the exact number of traps in the water at any time is not known, fishers in Maine use considerably more traps than in other lobster fisheries around world, including in Canada’s Lobster Fishing Area 34, which accounts for the highest proportion of landings in Nova Scotia (Myers and Moore 2020).Footnote 2 We return to this point in our discussion.

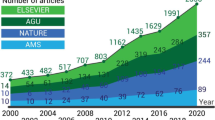

Although herring has long been an important source of bait in the lobster fishery, herring quotas in the Gulf of Maine have been reduced over the past 20 years due to the decline of the herring population (Fig. 2). The decline of herring is believed to be linked to multiple factors, including a shift in the abundance and distribution of its primary food source, the copepod Calanus finmarchicus, caused by changing environmental conditions (Runge and Jones 2012; Record et al. 2019),Footnote 3 and overfishing (ASMFC 2019). While the herring stock has been declining for some time, the federal government sharply reduced catch limits for herring from 104 800 mt in 2018 season to 15 065 mt in 2019 (NOAA 2018), representing an 85% decrease. The reduction in herring quota exacerbated what was already viewed as a growing bait deficit in the lobster industry (Overton 2016) and drove the price of herring to a 20-year high, which was 56% higher than that in the previous year and 180% higher than in 2010 (Appendix S1).

source: Northeast Fisheries Science Center (2019)

Annual Atlantic herring landings by management zone in the Gulf of Maine. Red dashed lines denote the upper and lower estimates of herring used in the lobster fishery per year (based on Grabowski et al. 2010). The blue bars represent herring landings across all management zones in the Gulf of Maine (1A–3). The orange bar represents the Allowable Catch Limit for herring in the 2019 fishing season across all zones. Data

Leading into the 2019 fishing season, there was widespread concern within the lobster fishery about the impending decline in herring availability, which was described by many as the bait crisis (MLA 2018). In general, the lobster industry faced three general pathways forward: (1) reduce fishing effort, gear, and bait use; (2) find new sources of local bait to fill the herring deficit; and/or (3) source alternative baits from outside the region. In this paper, we bring together both quantitative and qualitative data to investigate changes in bait use in the lobster fishery over an 18-year period and illustrate how, despite the seeming inevitability of the bait crisis, the lobster industry was able to navigate the situation without experiencing a major disruption. Our results draw attention to the alignment of actors' adaptive strategies across different sectors of the fishing industry and how existing institutions facilitated rapid adaptation. By studying this system, we seek to better understand the roles that institutions and agency play in sha** rapid responses to shocks.

Materials and methods

We used a mixed-methods approach and qualitative and quantitative data to investigate how bait use in the lobster industry changed over the course of nearly two decades, culminating in the industry's adaptation to a period of acute herring scarcity in 2019 that came to be called the bait “crisis”. Our methods included a longitudinal analysis of bait use in the lobster industry as well as in-depth interviews with stakeholders, participant observation, and media and policy analyses. One novel element of our approach was that our interviews and participant observation occurred in real-time during the 2019 fishing season, rather than retrospectively as is often the case with adaptation research. Understanding how different stakeholder groups respond to abrupt socioeconomic and environmental changes and how these adaptive strategies intersect is important because natural-resource systems are experiencing shocks with increasing regularity and this pattern will likely continue into the future as social-ecological processes become more interconnected (Cottrell et al. 2019; Kummu et al. 2020).

Characterizing changes in bait use

We characterized bait use in the Maine lobster industry using data from the Maine Lobster Sea Sampling Survey (LSSS) over an 18-year period from 2002 to 2019. The LSSS is a fisheries-dependent sampling program for lobster that has been conducted by the Maine Department of Marine Resources in partnership with Maine fishers since 1985.Footnote 4 The survey is conducted from May to November on commercial fishing vessels and is used to help assess the status of the lobster stock in the Gulf of Maine. The number of fishing trips has ranged from 152 to 256 per year. Data collected includes information about the location of fishing activities, environmental conditions, lobster catch, and number of traps hauled and set. In 2001, new data fields were added to the LSSS to include information about the types, quantity, and product form (e.g., fresh, frozen) of bait being used by fishers. In this study, all bait quantities were standardized to pounds, since bait units reported on the LSSS were by container type (e.g., barrels, totes, buckets, etc.). Conversions were based on information provided by the Maine Department of Marine Resources and verified by key informants involved in the lobster industry (Appendix S2). The origin of bait (i.e., where it was sourced from) was estimated using the Maine Department of Marine Resource’s Approved Marine and Freshwater Bait Lists, which specify which species are allowed to be used as bait in the lobster fishery and where they can be sourced. In cases where a particular bait type could have been sourced from either a local or non-local area (e.g. herring), we assumed that the fresh product form was locally sourced and the frozen product form was harvested outside the Gulf of Maine region. One acknowledged limitation of using LSSS data to estimate bait use is that fishers’ participation in the LSSS survey is voluntary. However, previous work by Scheirer et al. (2004) has investigated the potential bias introduced by the non-random sampling methodology. They found no statistical difference in annual catch per unit effort at the state level between the LSSS data and that from a port sampling program that used a random sampling design. The port sampling program is no longer operational and therefore was not used in this study.

Understanding adaptation strategies

In addition to analyzing the LSSS data, we conducted 60 semi-structured interviews with 52 people involved in the lobster industry between January and September 2019 to understand how the lobster industry was adapting in real-time to the herring crisis triggered by the 2019 herring quota reduction. We defined “involvement” in the lobster industry broadly to include those who fish for lobster as well as actors that work to support the fishing fleet (Table 1). By taking an expanded view of the Maine lobster industry, we acknowledge that fishery systems extend beyond those who target and catch marine resources and include those within the supply chain as well as decision-makers, researchers, and advocacy groups (Charles 2001; Stoll et al. 2015). Fourteen interviewees held more than one role in the industry (e.g., as a fisher and lobster dealer). Eight individuals were interviewed twice during the study period to understand how their perspectives on bait availability had changed during the season or to clarify previous statements. Interviewees ranged in age from their mid-20s to late-70s, and 39 were male and 13 were female. Interviews were geographically distributed across the state from the western most country to the eastern most county in order to minimize the potential for regional biases. Four interviews were conducted with individuals who were based outside the state of Maine, but who were involved in bait trade. Interviews were conducted in-person at a place of the interviewees’ preference or via phone if meeting in-person was not practical (Appendix S3). Participants were recruited through targeted intercepts at fishing ports, industry meetings, and through snowball sampling methods (Bernard 2013). Interviews were open-ended and conversational, using a blended approach of interview techniques, including structured interview questions and passive interviewing that allows the respondent space and time to tell their story (Steckler et al. 1992). Interviews focused on understanding the range of perspectives associated with the herring deficit, diverse strategies used to deal with decreasing availability of herring, and interactive effects of simultaneous innovations and actions by stakeholder groups within the bait supply chain (Appendix S4). Interviews ranged from approximately 30 min to over 2 h. All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. In this study, we relied on a concept known as “saturation” or the point at which new ideas or concepts are not generated by including additional interviews, to guide our sampling strategy. While researchers are not able to predetermine the number of interviews that are necessary for reaching saturation, work by Guest et al. (2006) suggests that the number of new concepts diminishes sharply after as few as 12 interviews and nears zero after 30 interviews. In our case, since we were studying a dynamic process in real-time, we conducted well over the 30-interview threshold (n = 60).

Interviews were analyzed in NVivo (v. 12.3.0) and coded, using grounded theory to identify emergent themes and triangulate relationships between adaptation strategies used by different sectors in the supply chain (Corbin and Strauss 2008). To ensure reliability and replicability of our data analysis, two members of our research team co-developed a coding tree based on an emergent process where we reviewed a subset of the interview data to create a set of nested topics. After establishing the coding tree, we then independently coded multiple interviews. Once this was completed, we compared our codes to evaluate consistency by calculating a Cohen’s kappa co-efficient, which is a widely used to evaluate inter-rater reliability. Kappa scores are on a scale from 0 to 1 with 0 indicating no overlap in coding (very bad) and 1 indicating perfect overlap in coding. Researchers typically aim for a 0.75 Kappa score. In our case, we conducted two rounds of joint coding for comparison. After the first round, we reviewed the differences we observed and clarified several of the categories we had created. We note that our Kappa score during the second of review was below 0.75, but NVivo calculates scores based on an exact text match, which leads to artificially low scores. We have added additional details to the methods section to clarify our process. In addition to these interviews, our research team attended numerous industry meetings, regularly interacted with members of the lobster industry, followed relevant social media channels and news outlets, and tracked changes in policy and management. These latter activities helped to contextualize the interviews and our analysis of LSSS data.

Results

The raceway concept (Fig. 1) provides an analytical framework for studying adaptation to crisis. We apply it here to examine the bait crisis in the lobster fishery. We begin by focusing on bait use from 2002 to 2018 to establish the system trajectory prior to the 2019 crisis (T0–TS). Next, we analyze the adaptations deployed by fishers, bait dealers, and policymakers during the crisis to understand how the system changed in response to the crisis (TS–TR).

System trajectory (T 0–T S): Moving away from herring, but not bait

Bait use in the Maine lobster fishery changed considerably between 2002 and 2018. Two predominant trends are visible in the LSSS data prior to the bait crisis in 2019. First, the lobster industry reduced its overall reliance on herring. LSSS data shows that the total proportion of herring (by weight) decreased from 85% in 2002 to 36% in 2018, with a period-high recorded in 2004 (89%) (Fig. 3). Herring was predominantly replaced by other types of marine fishes. In 2002, non-herring marine fishes represented only 12% of the overall bait portfolio in the lobster fishery, whereas by 2018 it had increased to 58%. According to interviewees, the shift to alternative baits was largely driven by the rising cost of locally sourced herring. By 2019, the average price of herring had increased to $0.42 per pound, equal to a 133% inflation-adjusted increase over a 10-year period (Appendix S1).

The fishing industry’s exposure to alternative baits prior to the 2019 bait crisis meant that fishers had experience using different types of baits and had gained confidence that it could be used to catch lobsters. As one bait dealer explained, “People have tried different stuff [bait] and I think they finally realized that you don't need a herring to catch a lobster. That always seemed to be the theory… And that's certainly not the case.”

In addition to using less herring, fishers also used progressively more types of bait per fishing trip. LSSS data shows that the mean number of baits used per trip increased steadily between 2002 and 2018, reaching a mean of 1.7 baits per trip in 2018 (Fig. 4A). The use of multiple baits reflects both the increasing availability of alternative baits as well as a shift in the role that bait plays as a fishing strategy. As one interviewee noted: “everyone has their own idea of what is the perfect combination of bait to catch lobster.” When there are dozens of types of bait for fishers to choose from, the species type, amount, preparation, and ratio of different baits can give fishers a competitive edge over their peers. As a result, bait use has become “a very personal decision,” explained one interviewee.

While there were changes in herring use (less herring) and bait diversification (more types of bait per trip), the amount of bait used per trap was relatively stable during the 17-year period leading up to the 2019 crisis. LSS data shows that bait use per trap ranged from 0.7 to 0.5 kg (Fig. 4B). In only 2 years (2005, 2013) was bait use more than 0.1 kg above or below the mean bait use (0.6 kg) for the study period and while there was a slight decrease in bait use per trap from 2016 to 2018, bait use in 2018 was below the mean by only 0.03 kg.

System raceway (T s–T R): Adaptation during the bait crisis

Fishery managers notified the public that herring quota in the Gulf of Maine would be reduced by 85% in early 2019, telegraphing the looming bait deficit that the lobster industry would face during the fishing season. Our interviews reveal that members of the lobster industry deployed a wide range of adaptation strategies in response to the perceived crisis. Broadly, these strategies can be subdivided into three categories related to efforts to: (1) reduce fishing effort, gear, and bait use; (2) find alternative local baits; and (3) source new baits from outside the region (Table 2). These adaptation strategies were imperfectly aligned and in some cases in conflict, yet our interviews and LSSS data suggest that the lobster industry as a whole successfully shifted to sourcing alternative baits from the Gulf of Maine and beyond. In the following subsections we report on the efforts of fishers, bait dealers, and decision-makers.

Fishers: Using less bait

Herring constituted 36% of the total bait used in the lobster fishery in 2018. Leading into the 2019 fishing season there was concern, as reported by multiple people we interviewed, that fishers would be slow, unwilling, or unable to switch to alternative baits because they were accustomed to using herring and viewed it as essential to catching lobsters or because enough alternative bait simply would not be available. However, fishers proved to be highly adaptive. Overall, fishers’ predominant adaptive strategies were consistent with the trajectory that the lobster industry was on leading up to 2019. First, LSSS data shows that the proportion of herring used as bait in the fishery dropped by 16% in 2019 (equal to 20% of the total bait portfolio). The change in herring use observed in 2019 was the largest single year shift in the 18-year dataset (Fig. 3).

To make up for the lack of herring in 2019, fishers pivoted to alternative baits (Fig. 4A). A particularly key alternative was Atlantic menhaden (Brevoortia spp.), which are locally referred to as “pogies” (Fig. 5). Pogies migrate sporadically into Maine waters in the summer months and form large aggregations close to shore that can be caught with gillnets. In 2019, pogies were abundant in the nearshore waters of the Gulf of Maine and through a special provision in the menhaden management, lobster fishers were able to obtain a fishing license that allowed them to land up to 2.7 mt of pogies per day.Footnote 5 Use of pogies was widely discussed among interviewees. One bait dealer, highlighting the alacrity with which lobster fishers started catching pogies, noted: “everybody now thinks that they are pogy fishermen” (i.e., because fishers were more focused on catching bait than lobsters). Interviewees also widely reported the use of other fish as alternative baits and indicated that some options worked better than herring at certain times of year and in certain locations. This diversification is reflected in the increase in number of types of baits used per fishing trip, which rose from 1.7 in 2018 to 2.0 in 2019 (note that this represents the largest single-year change in the dataset) (Fig. 4B).

Importantly, although some fishers reported using less bait and deploying bait saving gear, LSSS data indicates that these strategies did not lead to reduced bait use in the fishery. Mean bait use per trap for the 2019 season was 0.6 kg, slightly higher than the previous year.

Supply chain: Sourcing new baits

During the 2019 bait crisis, actors in the supply chain focused on sourcing alternative baits. Use of alternative baits in the lobster fishery has become increasingly commonplace over the last two decades. “It used to be simple,” explained one bait dealer we interviewed, “There was a lot of herring. You salted it, you stuck it in your traps, and everything was done. But now, everybody’s sourcing whatever they can possibly find.” This change is reflected in the diverse range of baits that became available to fishers. These included species such as Atlantic menhaden from the Gulf of Mexico, mid-Atlantic, Gulf of Maine, and maritime Canada; Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua)Footnote 6 from the Gulf of Maine and maritime Canada; and more exotic species from all around the world there were approved for use by regulators (Figs. 6, 7) (Appendix S5).

Harvest location of species approved for use as bait in the lobster fishery during the 2019 fishing season. Bait types color coded by IUCN Red List Status. See Appendix S5 for additional details

Freshwater, synthetic, and terrestrial baits also became available, including freshwater suckers, cowhide, and pig hide. These latter baits constituted a relatively small proportion (3 to 6%) of the total share of bait used by fishers between 2002 and 2018. However, the popularity of pig hide use increased in 2019 as fishers started to use it more regularly.Footnote 7 These reports are supported by the LSSS data for 2019 which included 61% of all of the documented cases of use of pig hide during the 18-year period. Much of this product is sourced from the Midwestern United States or abroad and is a byproduct in the pork industry.

In addition to pig hide, by 2019, the list of bait sources approved for use in Maine waters included more than 50 species from five continents (Fig. 7) (Appendix S5). Most of these baits fall into one of three categories: those that are directly targeted as bait; those that are caught as bycatch in other fisheries as sold as bait; and those that are targeted and sold as food fish whose waste from processing is used as bait. Based on species type and product form (i.e. fresh vs. frozen), an estimated 18% of all bait used in 2019 was sourced from outside the region (Fig. 5).

In discussing the diversification of baits and the geographic expansion of the supply system with those involved in bait sourcing, dealers reported that a primary motivation was a deep sense of responsibility towards fishers and the coastal communities where they live. As one dealer explained, “We may not be able to deal with herring, but we're going to be able to deal with other baits. We're going to survive this. We've fought so hard to have a sustainable industry, to protect our way of life that we've got this too. In the big picture, this is a speed bump and it's going to hurt, but we’re going to handle this fine.” Similar sentiments were also reflected by other dealers who shared comments like: “we do everything we can to help our guys,” “everyone’s trying to do what they can to help,” and “we’re here to support [lobster fishers].”

The bait crisis has helped to elevate bait sourcing from a mostly invisible practice that happens in the shadows of the lobster industry to one that is increasingly emblematic of the lobster industry’s dogged persistence and orientation towards solutions. The crisis has also changed people’s perceptions of bait and, in particular, expanded views on what constitutes “bait” as actors in the system work to source an ever more diverse and distal variety of baits. As one dealer explained, “all the fish in the world” has the potential to be bait.

Managers and policymakers: Legitimizing new sources of bait

Like fishers and supply chain actors, managers and policymakers also played a key role in navigating the bait crisis. Their efforts largely focused on hel** the lobster industry access alternative sources of bait. For example, state managers used their influence at the regional level to lobby to change the herring fishing season so that landings by herring fishers, particularly in the coastal zone off of Maine, would correspond with peak demand for bait in the lobster fishery. In doing so, they were able to successfully delay the start of the herring season by two months from the previous year from June to August. State managers also advocated for more herring and menhaden quota from the federal government, which helped to offset the anticipated deficit facing the industry during the 2019 fishing season.

Actions taken by managers and policymakers during the crisis were largely consistent with bait-related decisions that had been taken previously. In particular, managers and policymakers had previously created a vetting process to review and approve baits for use in the lobster industry. This process was established in 2015 to address increasing concern that bait sourced from outside the Gulf of Maine could pose a health risk to the marine environment by introducing diseases or pathogens. The vetting process is coordinated by the state and involves a volunteer advisory group made up of governmental, university, and private industry aquatic animal health professionals. The advisory group is responsible for reviewing prospective products that are put forward by actors who want to use or sell these products as bait.

A common view among those who we interviewed was that the vetting process serves an important function by hel** to buffer against environmental threats posed by new bait. However, some interviewees also expressed concerns about its inefficiency and felt that the slowness was a hindrance to their response to the bait crisis at a time when they needed to be nimble. Despite this critique, during the 2019 crisis, managers and policymakers mobilized to support the industry in diverse and often behind-the-scenes ways that were not always recognized or understood. For example, state managers actively pursued an arrangement with a state in the Midwestern United States that would have let bait dealers source the invasive species, Asian carp (Cyprinus carpio). The basic idea was that certain Midwest states were trying to get rid of Asian carp and needed a market for it, while fishers in Maine needed bait, so it was seen as a potential win–win situation. Ultimately, the effort was not implemented due to concerns about introducing Asian carp into other waterbodies, but it represented a significant investment of time and effort on the part of state managers and demonstrated their concern and attentiveness to the issue of bait supply. Furthermore, the very existence of the bait review process also represents a key contribution by managers and policymakers. This process, though imperfect and slow by the standards of the private sector, helped to legitimize their pursuit of alternative baits from around the world. In doing so, new bait types benefitted from the formal endorsement of the state. In this way, this regulatory process enabled the pursuit of alternative baits from around the world and acted to formalize the globalization of the bait system.

Discussion and conclusion

Adaptability is a topic of increasing focus as marine resource users around the world grapple with the impacts of rapid environmental and socioeconomic change. In the Gulf of Maine, one of the observed changes has been a decline in the abundance of Atlantic herring driven by changing climatic conditions and historical overfishing. In this article, we draw on institutional theory to develop the concept of “raceways” and define them as pathways of adaptation that simultaneously facilitate and constrain rapid responses to crises. We apply the concept as an analytical lens to understand how and why the Maine lobster industry was able to adapt to the sharp decline (85%) in the availability of locally-sourced herring.

One key factor that helped the lobster industry navigate the crisis was the timing of the summer lobster molt, which is when lobsters are most active and fishers typically target their fishing effort for the year. The molt occurred later in the year than normal due cool spring temperatures in the region, leading to slow start to the 2019 fishing season. This delay was not without consequences because it meant fishers were not on the water fishing, but it also meant that fishers did not need as much bait early in the seasons. Nevertheless, the late start to the season did not fully ameliorate the bait deficit and members of the industry were still forced to pursue a diverse range of adaptation strategies (Table 2). While these strategies were not uncoordinated, the industry ultimately turned their focus towards sourcing alternative baits—as opposed to using less bait. Pogies proved to be a particularly important substitute because they were abundantFootnote 8 in the inshore waters of the Gulf of Maine in 2019 and fisheries managers in Maine were able to successfully advocate to federal regulators to increase the state’s quota for them. To fill the remaining gap, an estimated 18% of the bait used during the 2019 fishing season was imported from outside the region.

Each segment of the lobster industry played a role in transiting away from herring: (1) fishers readily tried new types of bait; (2) bait dealers built capacity and infrastructure to source and store bait; and (3) managers and policymakers acted to legitimize and support bait trade. The alignment of these efforts was imperfect, and we observed some tension between actors in different parts of the lobster industry. Efforts by fishers, for example, to catch their own bait were, to some extent, at odds with dealers who were simultaneously building and stockpiling bait in their cold storage facilities. However, taken as a whole, the industry’s responses to the crisis were largely synergistic. Fishers’ openness to use alternative baits, for instance, positively reinforced bait dealers who invested in the infrastructure and business relationships necessary to source and store new types of non-local baits. These efforts were further reinforced by policymakers and managers, who legitimized these efforts with supportive processes, rules, and regulations. Had any one of these segments of the lobster industry responded differently, the pivot to alternative baits would likely been more difficult or outright infeasible, leading to a situation where the bait crisis might have forced fishers to stop fishing. For example, had fishers been less open to using new baits, as some interviewees predicted early in 2019, bait dealers would have been less willing to source new types of bait. Similarly, had state fishery managers not invested in and bolstered the process for reviewing and approving new types of bait and instead taken a precautionary perspective that no imported baits could be used, efforts to source bait from outside the region could have been prohibited.

In reviewing this case, it is worth asking the simple question: why did the lobster industry converge around efforts to expand the bait market instead of focusing on, for example, using less bait? This question is especially important to consider given that there are well-known risks associated with the globalization of markets. For example, global markets can drive resource overexploitation and extirpating of local stocks (Berkes et al. 2006), disincentivize local governance (Basurto et al. 2013), create dependencies on expensive fishing and ship** technologies (Perry et al. 2011), disrupt local markets (Robards and Greenberg 2007), mask local ecological decline (Deutsch et al. 2007), and make coastal communities vulnerable to shocks in other places (Liu et al. 2013; Stoll et al. 2018). This latter point was driven home in the lobster fishery the following year. By early 2020, the price for lobster had declined sharply due to decreased demand for lobster in Asia as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic (Love et al. 2020). This led to a $21 million decline in lobster landings between March and June of 2020 compared to the previous year (NOAA 2018).

One possible explanation is that sourcing new bait was the only viable option to sustain the lobster industry. Yet this is not an entirely satisfactory conclusion. Indeed, there are other lobster fisheries around the world that use less bait and have less gear in the water. Just to the north of Maine, for example, fishers in Nova Scotia’s Lobster Fishing Area 34 use eight times less gear and have higher catch rates (Myer and Moore 2020). It is therefore not beyond the realm of possibility to imagine that the Maine lobster industry could have adapted to the bait crisis by reducing bait use instead of sourcing alternative bait. On the other hand, scholars like DiMaggio (1998) and McCay (2002) remind us that institutional contexts matter and that they create path dependencies that constrain options and opportunities. In the case of the lobster industry, this insight appears to be helpful in explaining how the industry was able to adapt so rapidly and why it took a potentially risky path.

In this paper, we propose the concept of pathways of rapid adaptation to crisis events or “raceways”. These raceways are useful because they enable rapid adaption following shocks, but that they are inherently bound by institutional contexts. While these raceways facilitate rapid and large-scale change, they also drive systems along trajectories they are already on, rather than new pathways that are transformative. In the case of the lobster fishery, the industry has been shifting away from its dependence of herring prior to 2019 and starting to use alternative baits when the bait crisis emerged. Rather than pivoting to a new way of doing business (i.e., using less bait), the lobster industry adapted towards the familiar by focusing on sourcing alternative baits (Fig. 8). In doing so, the crisis acted to accelerate the lobster industry’s movement away from herring and towards a broader and more global bait market.

Illustration of the “raceway” concept applied to the lobster industry’s rapid adaptation to the bait crisis. A Bait use per trip was stable prior to the bait crisis and did not change during the crisis; B Diversity of bait was increasing prior to the crisis and increased sharply during the crisis; C Use of herring was decreasing prior to the crisis and decreased sharply during the crisis; D Use of non-local baits was increasing prior to the crisis and increased sharply during the crisis. Note that in all cases the observed adaptation acted to accelerate the trajectory of the system, rather putting it on a path to transformation

In many ways, the lobster industry’s pivot very much follows the broader trend in the seafood economy, which has become increasingly globalized (Gephart and Pace 2015). Lobster from Maine is traded worldwide and represents one of the most important export commodities for the state—hundreds of millions of dollars of lobster are traded to Canada, China, and Europe alone (Stoll et al. 2018). This trajectory is intimately familiar to fishers, dealers, managers, and policymakers in Maine, as many have directly participated in and shaped these markets. Thus, while the geographic expansion of the bait market is a relatively new phenomenon, the lobster industry is quite accustomed to and dependent on working at a global scale. In other words, the outcome of the bait crisis is reflective of continued movement down a pathway as opposed to a new way of operating altogether.

As the bait distribution system continues to globalize, it will be important to be attentive to the potential hidden costs of expanding bait sourcing efforts. One such cost relates to new exposure to risk that will be introduced as new baits are adopted. As previously noted, fisheries managers established a committee of governmental, university, and private industry aquatic animal health professionals to conduct risk assessments and provide recommendations on the ecological risks associated with using different species of bait in the lobster fishery. These assessments help to ensure that the baits that are imported into Maine do not pose a threat to the Gulf of Maine ecosystem. However, introducing new baits into the lobster fishery has potential implications for the health of lobsters themselves, which is not currently being considered in these assessments. Research in the Gulf of Maine have shown that bait represents an important component of lobsters’ diet and has a measurable impact of growth (Grabowski et al. 2010). This means that as fishers shift away from herring, a key food source for lobster will change, potentially having spillover effects on lobster growth and reproduction long-term. There are also potential implications that extend beyond the environment. For example, expanding markets creates new socioeconomic linkages between places that did not exist previously (Liu et al. 2013). As these new linkages become solidified, multiple socioeconomic questions and issues arise. For example, the current list of approved baits includes multiple species that the International Union for Conservation of Nature lists as threatened, endangered, or critically endangered (Fig. 7. Appendix S5). Even if these species are being used in a limited fashion, the fact that they are approved for use as bait raises critical questions about how they could impact consumers' perceptions of the sustainability of the fishery—which has long been one of its defining features—or how they will impact the fishery’s Marine Stewardship Council certification.Footnote 9 Questions like these underscore the need for being attentive to the long-term implications of adaptation strategies and the role that institutions play in creating raceways that facilitate and constrain marine resource users’ responses to crises. We suggest that further attention to raceways may be useful in understanding how and, in particular, why marine resource users and coastal communities adapt in particular ways in the face of shocks and crises.

Notes

A large share of the US lobster supply is traded to Canada, where it is processed and re-exported around the world.

According to Myers and Moore (2020), Maine lobster fishers used 7.55 times more traps than their counterparts in LFA 34. We note that this estimate is based on the number of trap tags sold in Maine as opposed to the number of traps fished.

Lipid rich C. finmarchicus are a key food source for many marine organisms and constitute 75% of adult herring’s diet in the nearshore coastal zone in the Gulf of Maine (Runge and Jones 2012). Changing ocean conditions have negatively impacted C. finmarchicus and its abundance has declined by 30% in parts of the Gulf of Maine (Record et al. 2019).

The survey was started in 1985, but the current iteration of coastwide sampling started in 1998.

For a description of the licensing system in Maine, see (Stoll et al. 2016).

In some cases, fish carcasses called “racks” are used.

One bait producer estimated that upwards of 4500 mt of pig hide would be used during the 2019 fishing season alone.

Pogies are migratory and enter the inshore waters of Gulf of Maine during summer months. There abundance changes from year-to-year and they happened to be particularly abundant in 2019 due to episodic trends in the fishery.

We note that during the process of writing this paper, the Marine Stewardship Council suspended its certification for lobster.

References

Adger, W.N. 2005. Social-ecological resilience to coastal disasters. Science 309: 1036–1039. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1112122.

Alexander, G. 2001. Institutions, path dependence, and democratic consolidation. Journal of Theoretical Politics 13: 249–270.

ASMFC. 2019. Addendum II to Amendment 3 to the Atlantic Herring Interstate Fishery Management Plan. http://www.asmfc.org/uploads/file/5cddb296Atl.HerringDraftAddendumIIFinalApprovedRevised.pdf.

Barnett, J., and N. Adger. 2003. Climate dangers and atoll countries. Climatic Change 61: 321–337.

Basurto, X., S. Gelcich, and E. Ostrom. 2013. The social–ecological system framework as a knowledge classificatory system for benthic small-scale fisheries. Global Environmental Change 23: 1366–1380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.08.001.

Bennett, N.J., H. Govan, and T. Satterfield. 2015. Ocean grabbing. Marine Policy 57: 61–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2015.03.026.

Berkes, F., T. Hughes, R.S. Steneck, J.A. Wilson, D.R. Bellwood, B. Crona, C. Folke, L. Gunderson, et al. 2006. Globalization, roving bandits, and marine resources. Science 311: 1557–1558. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1122804.

Bernard, H.R. 2013. Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches, 2nd ed. Los Angeles: Sage Publishing Inc.

Campbell, L.M., L. Fairbanks, G. Murray, J.S. Stoll, L. D’Anna, and J. Bingham. 2021. From Blue Economy to Blue Communities: reorienting aquaculture expansion for community wellbeing. Marine Policy 124: 104361.

Charles, A.T. 2001. Sustainable fishery systems. Oxford: Blackwell Science.

Colburn, L.L., and M. Jepson. 2012. Social indicators of gentrification pressure in fishing communities: A context for social impact assessment. Coastal Management 40: 289–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/08920753.2012.677635.

Corbin, J., and A. Strauss. 2008. Basics of qualitative research, 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publishing Inc.

Cote, M., and A.J. Nightingale. 2012. Resilience thinking meets social theory: Situating social change in socio-ecological systems (SES) research. Progress in Human Geography 36: 475–489. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132511425708.

Cottrell, R.S., K.L. Nash, B.S. Halpern, T.A. Remenyi, S.P. Corney, A. Fleming, E.A. Fulton, S. Hornborg, et al. 2019. Food production shocks across land and sea. Nature Sustainability 2: 130–137. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-018-0210-1.

Deutsch, L., S. Gräslund, C. Folke, M. Troell, M. Huitric, N. Kautsky, and L. Lebel. 2007. Feeding aquaculture growth through globalization: exploitation of marine ecosystems for fishmeal. Global Environmental Change 17: 238–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.08.004.

DiMaggio, P. 1998. The new institutionalisms: Avenues of collaboration. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics 154: 696–705.

Driscoll, J., C. Boyd, and P. Tyedmers. 2015. Life cycle assessment of the Maine and southwest Nova Scotia lobster industries. Fisheries Research 172: 385–400.

Folke, C., S.R. Carpenter, B.H. Walker, M. Scheffer, T. Chapin, and J. Rockstrom. 2010. Resilience thinking: Integrating resilience, adaptability and transformability. Ecology and Society 15: 20–29.

Gephart, J.A., and M.L. Pace. 2015. Structure and evolution of the global seafood trade network. Environmental Research Letters 10: 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/10/12/125014.

Giddens, A. 1979. Central problems in social theory: Action, structure, and contradiction in social analysis. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Garud, R., C. Hardy, and S. Maguire. 2007. Institutional entrepreneurship as embedded agency: An introduction to the special issue. Organization Studies. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840607078958.

Grabowski, J.H., E.J. Clesceri, A.J. Baukus, J. Gaudette, M. Weber, and P.O. Yund. 2010. Use of herring bait to farm lobsters in the Gulf of Maine. PLoS ONE 5: e10188–e10211. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0010188.

IPCC. 2018. Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty, ed. Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J.B.R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M.I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, and T. Waterfield.

Kay, A. 2005. A critique of the use of path dependency in policy studies. Public Administration 83: 553–571.

Kummu, M., P. Kinnunen, E. Lehikoinen, M. Porkka, C. Queiroz, E. Röös, M. Troell, and C. Weil. 2020. Interplay of trade and food system resilience: Gains on supply diversity over time at the cost of trade independency. Global Food Security 24: 100360.

Lawrence, T.B., and N. Phillips. 2004. From Moby Dick to Free Willy: Macro-cultural discourse and institutional entrepreneurship in emerging institutional fields. Organization 11: 689–711.

Lounsbury, M., and E.T. Crumley. 2007. New practice creation: An institutional perspective on innovation. Organization Studies 28: 993–1012.

Love, D., E. Allison, F. Asche, B. Belton, R. Cottrell, H. Froehlich, J. Gephart, C. Hicks, D. Little, L. Nussbaumer, P. Pinto da Silva, F. Poulain, A. Rubio, J. Stoll, M. Tlusty, A. Thorne-Lymann, M. Troell, and W. Zhang. 2020. Emerging COVID-19 impacts, responses, and lessons for building resilience in the seafood system. Global Food Security 28: 100494.

Maguire, S., C. Hardy, and T.B. Lawrence. 2004. Institutional entrepreneurship in emerging fields: HIV/AIDS treatment advocacy in Canada. Academy of Management Journal 47: 657–679.

Marshall, N.A., R.C. Tobin, P.A. Marshall, M. Gooch, and A.J. Hobday. 2013. Social vulnerability of marine resource users to extreme weather events. Ecosystems 16: 797–809. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-013-9651-6.

McCay, B.J. 2002. Emergence of institutions for the commons: Contexts, situations, and events. In The drama of the commons, 361–402.

McLaughlin, P. 2011. Climate change, adaptation, and vulnerability. Organization & Environment 24: 269–291. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026611419862.

McLaughlin, P., and T. Dietz. 2008. Structure, agency and environment: Toward an integrated perspective on vulnerability. Global Environmental Change 18: 99–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2007.05.003.

ME DMR. 2019. Historical Maine Lobster Landings. Maine Department of Marine Resources.

MLA Staff. 2018. Are you ready for the 2019 bait crisis? Maine Lobstermen’s Community Alliance.

Mosse, D. 1997. The symbolic making of a common property resource: History, ecology and locality in a tank-irrigated landscape in South India. Development and Change 28: 467–504.

Myers, H.J., and M.J. Moore. 2020. Reducing effort in the US American lobster (Homarus americanus) fishery to prevent North Atlantic right whale (Eubalaena glacialis) entanglements may support higher profits and long-term sustainability. Marine Policy 118: 104017.

NEFSC. 2019. Atlantic Herring Quota Data 2010-2019. Northeast Fisheries Science Center.

NOAA. 2018. Fisheries of the United States, 2017, 1–169. Washington, DC: US Department of Commerce.

North, D. 1990. Transaction costs, institutions, and economic performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nye, J.A., J.S. Link, J.A. Hare, J.A. Hare, and W. Overholtz. 2009. Changing spatial distribution of fish stocks in relation to climate and population size on the Northeast United States continental shelf. Marine Ecology Progress Series 393: 111–129. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps08220.

Ostrom, E. 1990. Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Perry, R.I., R.E. Ommer, M. Barange, S. Jentoft, B. Neis, and U.R. Sumaila. 2011. Marine social-ecological responses to environmental change and the impacts of globalization. Fish and Fisheries 12: 427–450. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-2979.2010.00402.x.

Pershing, A., M. Alexander, C. Hernandez, L. Kerr, A. Le Bris, K. Mills, J. Nye, N. Record, et al. 2015. Slow adaptation in the face of rapid warming leads to collapse of the Gulf of Maine cod fishery. Science 350: 805–809. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac5660.

Pierson, P. 2000. Increasing returns, path dependence, and the study of politics. American Political Science Review 94: 251–267.

Prell, C., M. Reed, L. Racin, and K. Hubacek. 2010. Competing structure, competing views: The role of formal and informal social structures in sha** stakeholder perceptions. Ecology and Society 15: 1–18.

Raitsos, D.E., G. Beaugrand, D. Georgopoulos, A. Zenetos, A.M. Pancucci-Papadopoulou, A. Theocharis, and E. Papathanassiou. 2010. Global climate change amplifies the entry of tropical species into the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Limnology and Oceanography 55: 1478–1484. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2010.55.4.1478.

Record, N., J. Runge, D. Pendleton, W. Balch, K. Davies, A. Pershing, C. Johnson, K. Stamieszkin, et al. 2019. Rapid climate-driven circulation changes threaten conservation of endangered North Atlantic Right Whales. Oceanography 32: 1–8. https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2019.201.

Robards, M.D., and J.A. Greenberg. 2007. Global constraints on rural fishing communities: Whose resilience is it anyway? Fish and Fisheries. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-2979.2007.00231.x.

Runge, J. A., and Jones, R. J. 2012. Results of a collaborative project to observe coastal zooplankton and ichthyoplankton abundance and diversity in the western Gulf of Maine: 2003–2008. In American Fisheries Society, Symposium, vol. 79. Chicago.

Saila, S.B., S.W. Nixon, and C.A. Oviatt. 2002. Does lobster trap bait influence the Maine inshore trap fishery? North American Journal of Fisheries Management 22: 602–605. https://doi.org/10.1577/1548-8675.2002.02.022.

Scheirer, K., Y. Chen, and C. Wilson. 2004. A comparative study of American lobster fishery sea and port sampling programs in Maine: 1998–2000. Fisheries Research 68: 343–350.

Silver, J.J., N.L. Gray, L.M. Campbell, L.W. Fairbanks, and R.L. Gruby. 2015. Blue economy and competing discourses in international oceans governance. The Journal of Environment & Development 24: 135–160.

Smit, B., and J. Wandel. 2006. Adaptation, adaptive capacity and vulnerability. Global Environmental Change 16: 282–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.03.008.

Smit, B., I. Burton, R. Klein, and J. Wandel. 2000. An anatomy of adaptation to climate change and variability. Climatic Change 45: 223–251.

Steckler, A., K. McLeroy, R. Goodman, S. Bird, and L. McCormick. 1992. Toward integrating qualitative and quantitative. Health Education Quarterly 19: 1–8.

Stoll, J.S. 2017. Fishing for leadership: The role diversification plays in facilitating change agents. Journal of Environmental Management 199: 74–82.

Stoll, J.S., B.I. Crona, M. Fabinyi, and E.R. Farr. 2018. Seafood trade routes for lobster obscure teleconnected vulnerabilities. Frontiers in Marine Science 5: 587–588. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2018.00239.

Stoll, J.S., C.M. Beitl, and J.A. Wilson. 2016. How access to Maine’s fisheries has changed over a quarter century: The cumulative effects of licensing on resilience. Global Environmental Change 37: 79–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.01.005.

Stoll, J.S., P. Pinto da Silva, J. Olson, and S. Benjamin. 2015. Expanding the “geography” of resilience in fisheries by bringing focus to seafood distribution systems. Ocean and Coastal Management 116: 185–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2015.07.019.

Torfing, J. 2001. Path-dependent Danish welfare reforms: The contribution of the new institutionalisms to understanding evolutionary change. Scandinavian Political Studies 24: 277–309.

United Nations. (2021). UN Comtrade Database. Available online https://comtrade.un.org/.

Walker, B.H., C.S. Holling, S.R. Carpenter, and A. Kingzig. 2004. Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social-ecological systems. Ecology and Society 9: 1–14.

Welter, F., and D. Smallbone. 2011. Institutional perspectives on entrepreneurial behavior in challenging environments. Journal of Small Business Management 49: 107–125.

Worm, B., E.B. Barbier, N. Beaumont, J.E. Duffy, C. Folke, B.S. Halpern, J. Jackson, H.K. Lotze, et al. 2006. Impacts of biodiversity loss on ocean ecosystem services. Science 314: 787–790. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1132294.

Acknowledgements

We extend our appreciation to the many people in the lobster industry who took the time to share their insights, perspectives, and experiences with us during the extent of this project. Special thanks to Kathryn Connelly for hel** navigate and access the NMFS herring landings and dealer data. We also thank three anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback, which greatly improved the manuscript. JSS and PPS was supported by grant funding from the Office of Science and Technology at the National Marine Fisheries Service [Project Number: 37055812]. DCL is supported by funds from the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JSS, PDS, DCL, and TW contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by JSS, TW, KR, and EJO. The first draft of the manuscript was written by JSS, and EJO and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stoll, J.S., Oldach, E.J., Witkin, T. et al. Rapid adaptation to crisis events: Insights from the bait crisis in the Maine lobster fishery. Ambio 51, 926–942 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-021-01617-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-021-01617-8