Abstract

As a result of the expansion of higher education exports, the number of international students in China increased from 44,711 in 1999 to 492,185 in 2018, with an average yearly growth rate of 14%. This paper investigates whether the export of higher education improves households’ well-being in China. Specifically, we study if there is a causal relationship between higher education exports and household consumption. Using a shift-share instrumental variable approach, we find that a one percent increase in educational exports (measured as the number of international students) increased household consumption by around 0.06%. The results indicate that growth in income/wealth is an important channel that promotes household consumption. Furthermore, we find that education exports mainly affect household developmental consumption, especially housing and education consumption. We also find that the promotion effect of education export on household consumption is not driven by tuition fees alone. Finally, a vital conclusion of our work is that education exports not only can bring more trade benefits but also can relieve the negative consequences of the low household consumption rate in China.

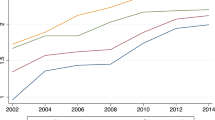

Source: IIE/Project Atlas

Source: Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China

Source: Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Yes.

Notes

Here “externality” and “exogeneity” refer to “the instrument is not caused by variables in the outcome equation” and “validity of the IV exclusion restriction” respectively.

Saiz (2007) proposed an alternative IV approach which can relax the second assumption and consist in estimating annual immigration inflows by country and year. However, due to the lack of the source country information of international student, we are not able to build this kind of instrument in this study, even so we still believe that this assumption is somewhat close to reality.

The CFPS is sponsored by the Chinese government through Peking University. CFPS implemented its baseline survey in 2010 and four waves of full sample follow-up surveys in 2012, 2014, 2016, and 2018, we do not use the 2018 wave since some variables in the 2018 database have changed, and we have the international students data until 2017.

The CFPS baseline survey interviewed a total of 14,960 households and 42,590 individuals, which covers 25 provinces/municipalities/autonomous regions, representing 95% of the Chinese population.

According to the definition of the National Bureau of Statistics, consumer expenditure includes eight major items including food, clothing, household equipment and services, medical care, transportation and communications, entertainment, education and cultural services, housing, miscellaneous goods and services.

Here food refers to expenditures on food, dress refers to expenditures on clothing, house refers to expenditures on housing, daily refers to expenditures on family equipment and daily necessities, medical refers to expenditures on medical and fitness, education refers to expenditures on education and entertainment, transportation refers to expenditures on communication and transportation, and other refers to other expenditure on consumption.

The annual statistical data of international students in China consists of three parts: students who graduated that year, new students who come to China that year, and students who continue to study.

We choose the variable of net family income which is compared with the year 2010 in every database.

The nominal interest rate refers to the official 1-year savings deposit interest rate (Wan et al., 2001).

According to Engel’s Law, as family income increases, the percentage spent on food decreases, that spend on clothing, heat, and light remains may be the same, while that spent on education and recreation increases. From the results of Table 3, we can see that with income growth, the household consumption on food, dress, medical, and daily didn’t change, while the consumption on housing, education, and transportation significantly increased. Therefore, we think these results follow Engel’s Law.

The Chinese government established the Chinese government scholarship policy in the 1950s to subsidize students and scholars from all over the world to study and research in Chinese universities. The Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China entrusts the Management Committee of China Scholarship Council to be responsible for enrollment and management of Chinese government scholarship programs. Chinese government scholarships are divided into undergraduate scholarships, postgraduate scholarships, doctoral scholarships, scholarships for Chinese language learners, scholarships for generally advanced learners, and scholarships for advanced learners. Chinese government scholarships are divided into full scholarships and partial scholarships. Full scholarships include tuition reduction and exemption, accommodation fee exemption, fixed monthly living allowance, and public medical services equivalent to Chinese students, etc., and partial scholarships cover one of the full scholarships Or a few items. https://www.chinesescholarshipcouncil.com/.

Advanced scholars refer to international students who have a master’s degree or above and come to China for further studies on a particular topic. General scholars refer to international students who have a sophomore degree or above in China for advanced studies. Language advanced students refer to the international students whose purpose is studying and improving the Chinese language proficiency. Short-term students refer to those who study in China for less than one semester.

We also directly apply income data from CFPS to retest our mechanism. Specifically, we apply total family income and family salary income two variables, total family income can measure household income, and family salary income is a subcomponent of the household income. We report the results in Table A1.

Here housing price refers to average selling price of commercial housing, the unit is yuan/square meter. Data source: National Bureau of Statistics of China.

References

Adão, R., Kolesár, M., & Morales, E. (2019). Shift-share designs: Theory and inference. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 134(4), 1949–2010.

Australian Council for Private Education and Training. (2009). The Australian education sector and the economic contribution of international students

Barrett, B. (2015). International trade and higher education services: The TTIP, the EHEA, and beyond. In European consortium for political research

Bartik, T. J. (1991). Who benefits from state and local economic development policies? In W.E. UPJOHN INSTITUTE for employment research

Bashir, S. (2007). Trends in international trade in higher education: implications and options for develo** countries. In Education working paper series

Bhagwati, J., & Srinivasan, T. N. (2002). Trade and poverty in the poor countries. The American Economic Review, 92(2), 180–183.

Bonsu, C. O., & Muzindutsi, P. (2017). Macroeconomic determinants of household consumption expenditure in ghana: A multivariate cointegration approach. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 7(4), 737–745.

Bourke, A. (2000). A model of the determinants of international trade in higher education. Service Industries Journal, 20(1), 110–138.

Browning, M. (1992). Children and household economic behavior. Journal of Economic Literature, 30(3), 1434–1475.

Card, D. (2001). Immigrant inflows, native outflows, and the local labor market impacts of higher immigration. Journal of Labor Economics, 19(1), 22–64.

Card, D. (2009). Immigration and inequality. American Economic Review, 99(2), 1–21.

Chen, T., Liu, L. X., **ong, W., & Zhou, L.-A. (2017). Real estate boom and misallocation of capital in China. In Working paper

Clemens, M. A. (2009). Skill flow: a fundamental reconsideration of skilled-worker mobility and development. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1477129

Deaton, A. (1991). Saving and liquidity constraints. Econometrica, 59(5), 1221–1248.

Deaton, A. (2010). Instruments, randomization, and learning about development. Journal of Economic Literature, 48(2), 424–455.

Docquier, F., & Lodigiani, E. (2010). Skilled migration and business networks. Open Economies Review, 21(4), 565–588.

Erten, B., & Leight, J. (2019). Exporting out of agriculture: The impact of WTO accession on structural transformation in China. The Review of Economics and Statistics, pp. 1–46

Facchini, G., Liu, M. Y., Mayda, A. M., & Zhou, M. (2019). China’s “great migration”: The impact of the reduction in trade policy uncertainty. Journal of International Economics, 120, 126–144.

Frankel, J. A., & Romer, D. (1999). Does trade cause growth? American Economic Review, 89(3), 379–399.

Goldsmith-Pinkham, P., Sorkin, I., & Swift, H. (2020). Bartik instruments: what, when, why, and how. American Economic Review, 110(8), 2586–2624.

Gorbachev, O. (2011). Did household consumption become more volatile? American Economic Review, 101(5), 2248–2270.

Gu, Y., & Qiu, B. (2017). Foreign student education in china and china outward direct investment—empirical evidence from the countries along “one belt one road.” Journal of International Trade, 4, 83–94.

Guisan, M. C. (2004). A comparison of causality tests applied to the bilateral relationship between consumption and GDP in the USA and Mexico. International Journal of Applied Econometrics and Quantitative Studies, 1(1), 115–130.

Guiso, L., & Jappelli, T. (2002). Household portfolios in Italy. Household portfolios. MIT Press.

Hang, B. (2009). Rural household’s buffer-stock saving with habit formation. Economic Research Journal, 1, 96–105.

He, Z., & Song, X. (2020). How does digital finance promote household consumption? Finance & Trade Economics, 8, 65–79.

Hoekman, B., & Mattoo, A. (2012). Services trade and growth. International Journal of Services Technology and Management, 17, 232–250.

Jaeger, D., Ruist, J., & Stuhler, J. (2018). Shift-Share Instruments and the Impact of Immigration. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series.

**, T., & Tao, X. (2016). How government spending and opening up affect chinese residents’ consumption? On the basic of the exploration of chinese transformational growth mode affecting consumption. China Economic Quarterly, 16(1), 121–146.

José Luengo-Prado, M. (2006). Durables, nondurables, down payments and consumption excesses. Journal of Monetary Economics, 53(7), 1509–1539.

Kali, R., Méndez, F., & Reyes, J. (2007). Trade structure and economic growth. Journal of International Trade and Economic Development, 16(2), 245–269.

Khanna, G., Shih, K., Weinberger, A., Xu, M., & Yu, M. (2020). Trade liberalization and chinese students in US higher education. In The Center for Global Development Working Papers Series (No. 536)

Kim, D. H. (2011). Trade, growth and income. Journal of International Trade and Economic Development, 20(5), 677–709.

Komljenovic, J., & Lee Robertson, S. (2017). Making global education markets and trade. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 15(3), 289–295.

Kovak, B. B. K. (2016). American economic association regional effects of trade reform: What is the correct measure of liberalization ? The American Economic Review, 103(5), 1960–1976.

Krugman, P. (1980). Scale economies, product differentiation, and the pattern of trade. The American Economic Review, 70(5), 950–959.

Larsen, K., Martin, J. P., & Morris, R. (2002). Trade in educational services: trends and emerging issues. World Economy, 25(6), 849–868.

Li, L., Liu, B., & **e, L. (2011). The impacts of trade openness on urban residents’ income and its distribution. China Economic Quarterly, 11(1), 309–326.

Li, S. (2000). The impact of opening up on China’s economic growth. Journal of Financial Research, 246(12), 25–32.

Li, T., & Chen, B. (2014). Real assets, wealth effects and household consumption: Analysis based on china household survey data. Economic Research Journal, 3, 62–75.

Linder, S. B. (1961). An essay on trade and transformation. Wiley & Sons.

Liu, C., & **ong, W. (2018). China’s real estate market. In National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series

Lu, J., Ling, H., & Pan, X. (2019). Internationalization of China’s higher education service under the fully opening: An empirical analysis of the export of higher education service and the factors of international students studying to China. China Higher Education Research, 1, 22–27.

Mao, Q., & Sheng, B. (2011). Economic opening, regional market integration and total factor productivity. China Economic Quarterly, 11(1), 181–210.

Matsuyama, K. (1992). Agricultural productivity, comparative advantage, and economic growth. Journal of Economic Theory, 58(2), 317–334.

Modigliani, F., & Brumberg, R. (1954). Utility analysis and the consumption function: An interpretation of cross-section data. In Post Keynesian Economics

Modigliani, F., & Cao, S. L. (2004). The Chinese saving puzzle and the life-cycle hypothesis. Journal of Economic Literature, 42(1), 145–170.

Noguer, M., & Siscart, M. (2005). Trade raises income: A precise and robust result. Journal of International Economics, 65(2), 447–460.

OECD. (2012). Education at a glance 2012. OECD Publishing.

Parrotta, P., Pozzoli, D., & Pytlikova, M. (2014). Labor diversity and firm productivity. European Economic Review, 66, 144–179.

Pholphirul, P., & Rukumnuaykit, P. (2017). Does immigration always promote innovation? Evidence from thai manufacturers. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 18(1), 291–318.

Saiz, A. (2007). Immigration and housing rents in American cities. Journal of Urban Economics, 61(2), 345–371.

Siddiq, F., Nethercote, W., Lye, J., & Baroni, J. (2012). The economic impact of international students in atlantic Canada. International Advances in Economic Research, 18(2), 239–240.

Souleles, B. N. S. (1999). The response of household consumption to income tax refunds. The American Economic Review, 89(4), 947–958.

The World Bank Open Data. (2019). https://data.worldbank.org/

Thomas, M. P. (2019). Impact of services trade on economic growth and current account balance: Evidence from India. Journal of International Trade and Economic Development, 28(3), 331–347.

Tombe, T., & Zhu, X. (2019). Trade, migration, and productivity: A quantitative analysis of China. American Economic Review, 109(5), 1843–1872.

VanderWeele, T. J. (2016). Mediation analysis: A practitioner’s guide. Annual Review of Public Health, 37, 17–32.

Wan, G., Yin, Z., & Niu, J. (2001). Liquidity constraints, uncertainty and household consumption in China. Economic Research Journal, 11, 35–44.

Wang, X., Fan, G., & Liu, P. (2009). Transformation of growth pattern and growth sustainability in China. Economic Research Journal, 1, 4–16.

Waugh, M. E. (2010). International trade and income differences. The American Economic Review, 100(5), 2093–2124.

Yang, R., & Chen, B. (2009). Higher education reform, precautionary saving and consumer behavior. Economic Research Journal, 8, 113–124.

Zhou, M. (2003). On the new trends of international education service trade and China’s countermeasures. Educational Research, 276(1), 38–43.

Funding

This study was funded by Jiangsu Province Social Science Fund, 23JYB011, Yuanyuan Gu, the General Project of Philosophy and Social Science Research in Colleges and Universities in Jiangsu Province, 2022SJYB0167, Yuanyuan Gu, Startup Foundation for Introducing Talent of Nan**g University of Information Science and Technology, 2022r066, Yuanyuan Gu.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have not disclosed any competing interests.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Informed consent

Yes.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Gu, Y., García, J.A. Higher education exports and household consumption: evidence from China. Asia Pacific Educ. Rev. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-024-09932-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-024-09932-x