Abstract

Introduction

Patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) often have psychiatric comorbidities that may confound diagnosis and affect treatment outcomes and costs. The current study described treatment patterns and healthcare costs among patients with ADHD and comorbid anxiety and/or depression in the United States (USA).

Methods

Patients with ADHD initiating pharmacological treatments were identified from IBM MarketScan Data (2014–2018). The index date was the first observed ADHD treatment. Comorbidity profiles (anxiety and/or depression) were assessed during the 6-month baseline period. Treatment changes (discontinuation, switch, add-on, drop) were examined during the 12-month study period. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) of experiencing a treatment change were estimated. Adjusted annual healthcare costs were compared between patients with and without treatment changes.

Results

Among 172,010 patients with ADHD (children [aged 6–12] N = 49,756; adolescents [aged 13–17] N = 29,093; adults [aged 18 +] N = 93,161), the proportion of patients with anxiety and depression increased from childhood to adulthood (anxiety 11.0%, 17.7%, 23.0%; depression 3.4%, 15.7%, 19.0%; anxiety and/or depression 12.9%, 25.4%, 32.2%). Compared with patients without the comorbidity profile, those with the comorbidity profile experienced a significantly higher odds of a treatment change (ORs [children, adolescents, adults] 1.37, 1.19, 1.19 for those with anxiety; 1.37, 1.30, 1.29 for those with depression; and 1.39, 1.25, 1.21 for those with anxiety and/or depression). Excess costs associated with a treatment change were generally higher with more treatment changes. Among patients with three or more treatment changes, annual excess costs per child, adolescent, and adult were $2234, $6557, and $3891 for those with anxiety; $4595, $3966, and $4997 for those with depression; and $2733, $5082, and $3483 for those with anxiety and/or depression.

Conclusions

Over 12 months, patients with ADHD and comorbid anxiety and/or depression were significantly more likely to experience a treatment change than those without these psychiatric comorbidities and incurred higher excess costs with additional treatment changes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is commonly associated with psychiatric comorbidities such as anxiety and depression that may confound diagnosis and management. |

Patients with ADHD and comorbid anxiety and/or depression may experience more frequent treatment changes and higher healthcare costs than those without these comorbidities. |

What was learned from the study? |

The proportion of patients with comorbid anxiety and depression increased with age from childhood to adulthood; these patients were 20–40% more likely to experience a change in ADHD pharmacological treatment than those without the comorbidity profile and also incurred higher direct healthcare costs with additional treatment changes. |

Comorbid anxiety and/or depression in ADHD was common and added to treatment and cost burden; these comorbidities must be taken into account when formulating treatment strategies in ADHD management. |

Introduction

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurobiological disorder that typically begins in childhood with symptoms commonly persisting into adulthood [1]. In the USA, the estimated prevalence of ADHD is 10.0% in children, 6.5% in adolescents, and 4.4% in adults [2,3,4]. Patients with ADHD exhibit symptoms of hyperactivity, impulsivity, and/or inattention that impair academic, occupational, and social functioning [5], which translate into a substantial clinical and economic burden. The incremental direct healthcare costs incurred by children, adolescents, and adults with ADHD in the USA have been estimated at approximately $23 billion [6, 7].

ADHD is commonly comorbid with psychiatric conditions such as anxiety and depression that may confound the diagnosis and management of ADHD [3, 8,9,10,11,12]. Differential diagnosis can be difficult as many comorbidities share overlap** symptoms with ADHD [9, 13, 14]. The presence of comorbidities may also increase the severity of ADHD symptoms [15,16,17]; for instance, patients with ADHD and comorbid anxiety have been shown to display more symptoms of attention deficit and more social problems than those with ADHD or anxiety only [15]. Further adding to the management challenges is the variable response of comorbid symptoms to ADHD treatment [18]. While some comorbid symptoms may improve when ADHD is controlled, others may require additional treatments [9, 12, 13, 18]. Notably, additional treatments may elevate the risk of complications and increase treatment costs [13, 19, 20].

As such, patients with ADHD and comorbidities represent a challenging population to manage and warrant specific attention to help identify potential avenues of improvement in patient care. Previous treatment pattern studies using commercial claims databases in the USA have found frequent treatment changes in the overall population of patients with ADHD, and that those treatment changes are associated with increased healthcare costs [19, 20]. As patients with ADHD and a comorbid condition such as anxiety or depression may be more complex to diagnose and manage, it is speculated that these patients may have more frequent treatment changes and higher healthcare costs than those without a comorbid condition. Therefore, this study aimed to describe the ADHD pharmacological treatment patterns, odds of experiencing a treatment change, and direct healthcare costs among commercially insured patients who had ADHD with or without comorbid anxiety and/or depression in the USA.

Methods

Data Source

Claims data from the IBM MarketScan Commercial Database (Q1/2014–Q4/2018) were used. The database consists of medical and drug data of over 200 million individuals covered by employer-sponsored private health insurance and includes records of inpatient services, inpatient admissions, outpatient services, and prescription drug claims. Data are de-identified and comply with the patient requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Therefore, no institutional review board exemption nor informed consent was required.

Study Design

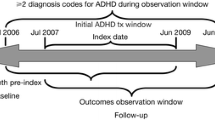

A retrospective claims-based analysis was conducted to assess treatment patterns of patients with ADHD newly initiating a Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved ADHD pharmacological treatment as previously described [19, 20]. The index date was defined as the first observed ADHD prescription fill date that was preceded by at least a 6-month treatment gap (i.e., washout period to capture newly initiated treatment episode). The baseline period was the 6 months before the index date. The study period was the 12 months after index date. The follow-up period was the 6 months following the study period; the additional 6 months allowed for sufficient time to determine treatment changes within the entirety of the 12-month study period.

Patient Populations

Details on patient selection criteria have been described previously [19, 20]. Briefly, patients were included if they had two or more diagnoses of ADHD on distinct dates (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth/Tenth revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM codes 314.0x; ICD-10-CM codes F90.x]), had one or more prescription fill for an FDA-approved ADHD treatment (i.e., stimulants and non-stimulants) on or after the first observed ADHD diagnosis, and received no ADHD treatment 6 months prior to the index date. All patients included in this study were required to have 18 months of continuous health plan enrollment following the index date (i.e., 12-month study period and 6-month follow-up period).

Patients were stratified by comorbidity profiles of interest (i.e., anxiety, depression, and anxiety and/or depression), which were assessed during the 6-month baseline period using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) ICD-9/10-CM coding recommendations (see Supplementary Table 1 for the list of codes) [5]. Patients with ADHD who had no comorbid anxiety or depression observed during the baseline period were considered to have no comorbidity profile of interest (i.e., the without comorbidity cohort).

For the cost analysis, patients with a comorbidity profile who had at least one treatment change following the ADHD diagnosis observed during the 12-month study period were further stratified into three mutually exclusive cohorts based on the number of treatment changes observed (i.e., 1, 2, or ≥ 3).

Study Measures and Outcomes

Study measures and outcomes included baseline patient characteristics (e.g., age, gender, comorbidities), treatment characteristics (e.g., types of index pharmacological treatment at the class and agent levels, use of treatment combinations [i.e., two or more ADHD-related agents] and/or psychotherapy, and treatment duration of the first regimen observed), treatment changes, and total annual direct healthcare costs associated with treatment changes.

Definitions for a treatment regimen and treatment changes were as previously published [19, 20]. Briefly, treatment discontinuation was defined as no ADHD-related agents for at least 180 consecutive days after the last day of supply of the treatment regimen; treatment switch was defined as initiation of a new ADHD-related agent with no prescription fills from the previous treatment regimen within the 30 days following initiation; treatment add-on was defined as initiation of a new ADHD-related agent with one or more other prescription fill from the previous treatment regimen within the 30 days following initiation; and treatment drop was defined as discontinuation of an ADHD-related agent while other agent(s) were not discontinued. The frequency and odds of experiencing a treatment change were examined during the 12-month study period.

Total annual direct healthcare costs included medical (i.e., inpatient, outpatient, and emergency department visits) and pharmacy costs and were measured from the index date until the end of the 12-month study period. Costs were assessed from the payers’ perspective and reported in 2019 US dollars.

All measures and outcomes were reported separately by age group (i.e., children [aged 6–12 years], adolescents [aged 13–17 years], and adults [aged 18+ years]) and by comorbidity profile (i.e., anxiety, depression, and anxiety and/or depression).

Statistical Analysis

Baseline patient and treatment characteristics as well as frequency of treatment changes were described using means, standard deviations, and medians for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables.

Odds ratios (ORs) of experiencing a treatment change were estimated between patients with and without a comorbidity profile of interest using logistic regressions. Total annual direct healthcare costs were compared between patients with and without treatment changes using ordinary least-squares regression models.

ORs and cost differences were adjusted for the following a priori selected demographic and clinical characteristics that had a standardized difference of at least 0.1 between cohorts: age, gender, region, health plan, type of ADHD diagnosis, year of index date, and number of patients who had at least one psychotherapy visit (children only). Adjusted effect size was reported along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), using robust standard errors, and p values.

Results

Baseline Patient Characteristics

A total of 172,010 patients with ADHD met the study criteria, including 49,756 children, 29,093 adolescents, and 93,161 adults. The proportion of patients with anxiety and depression increased with age from childhood to adulthood. Among child, adolescent, and adult patients with ADHD, 11.0% (N = 5473), 17.7% (N = 5161), 23.0% (N = 21,416) had comorbid anxiety, respectively; 3.4% (N = 1712), 15.7% (N = 4562), 19.0% (N = 17,672) had comorbid depression, respectively; and 12.9% (N = 6424), 25.4% (N = 7390), 32.2% (N = 30,021) had comorbid anxiety and/or depression, respectively (Table 1). Patients’ mean age and gender ratio were similar within age groups irrespective of comorbidity profiles, while the proportion of individuals with ADHD and comorbid anxiety and/or depression who were female appeared to increase with age. Antidepressants and antianxiety medications were commonly used by patients with ADHD during the baseline period. The proportion of patients who used these medications were similar within age groups and increased from childhood to adulthood (Table 1).

Treatment Characteristics

The characteristics of the first ADHD treatment regimen observed for children, adolescents, and adults by comorbidity profile are presented in Table 2. Stimulants were the most prevalent first treatment observed in all age groups; the proportion of patients initiated on a stimulant across comorbidity profiles was approximately 83% among children, 88% among adolescents, and 93% among adults. Non-stimulants were initiated by approximately 20% of children, 14% of adolescents, and 8% of adults with ADHD across comorbidity profiles. While most child, adolescent, and adult patients initiated an ADHD-related agent in monotherapy, approximately 10–12% of patients were initiated on a combination therapy of two or more ADHD-related agents.

The mean treatment duration was approximately 6 months for children, 6 months for adolescents, and 7 months for adults with ADHD across comorbidity profiles. Throughout the duration of the first treatment regimen observed, the proportion of patients with ADHD across comorbidity profiles who also received psychotherapy was 60.5–71.3% among children, 68.8–74.2% among adolescents, and 52.8–58.7% among adults (Table 2).

Frequency and Odds of Experiencing a Treatment Change

Among patients with ADHD and a comorbidity profile, 66.1–66.9% of children, 71.4–73.1% of adolescents, and 61.4–63.0% of adults had experienced a change in ADHD pharmacological treatment within the 12-month study period; the proportion of patients without a comorbidity profile who had experienced a change in ADHD pharmacological treatment was 58.0% among children, 66.4% among adolescents, and 57.3% among adults (Fig. 1).

Compared with patients without a comorbidity profile, those with a comorbidity profile experienced a significantly higher odds of a change in ADHD pharmacological treatment (Fig. 2). The respective adjusted ORs for experiencing a treatment change in children, adolescents, and adults with ADHD were 1.37, 1.19, and 1.19 (all p < 0.05) for those with anxiety; 1.37, 1.30, and 1.29 (all p < 0.05) for those with depression; and 1.39, 1.25, and 1.21 (all p < 0.05) for those with anxiety and/or depression.

Adjusted odds ratios of experiencing a change in ADHD pharmacological treatment during the 12-month study period. Odds of experiencing a treatment change were estimated between patients with and without a comorbidity profile of interest using logistic regressions adjusted for the following demographic and baseline characteristics: age, gender, region, health plan, type of ADHD diagnosis, and year of index date. An OR > 1 indicates a higher odds of having the outcome. OR odds ratio. *Significant at the 5% level

Excess Direct Healthcare Costs Associated with Treatment Changes

Overall, a general positive relationship between the number of changes in ADHD pharmacological treatment and adjusted total excess direct healthcare costs was observed across age groups and comorbidity profiles (Fig. 3). The adjusted total annual healthcare cost differences incurred by children, adolescents, and adults with ADHD who had three or more treatment changes relative to those without a treatment change were $2234, $6557, and $3891 (all p < 0.05) for those with anxiety; $4595, $3966, and $4997 (all p < 0.05) for those with depression; and $2733, $5082, and $3483 (all p < 0.05) for those with anxiety and/or depression.

Adjusted annual direct healthcare cost differences between patients with a treatment change and those without a treatment change. Total annual direct healthcare cost differences were calculated during the 12-month study period based on the differences between patients who experienced 1, 2, or ≥ 3 treatment changes and those with the same comorbidity profile but did not experience a treatment change. Cost differences were estimated using ordinary least-squares regression models with robust standard errors and adjusted for the following demographic and baseline characteristics in which the standardized difference between those with and without a treatment change was ≥ 0.1: age, gender, region, health plan, type of ADHD diagnosis, year of index date, and number of patients with ≥ 1 psychotherapy visit (children only). USD US dollars. *Significant at the 5% level. Shaded bars indicate non-significance

Discussion

The current large-scale claims-based analysis among patients with ADHD in the USA demonstrated the added treatment and cost burden associated with comorbid anxiety and/or depression, which were commonly observed across ADHD populations of different ages. The prevalence of comorbid anxiety and depression in ADHD increased from childhood to adulthood, an observation that aligned with previous research [3, 16, 21, 22]. It was also noted that the proportion of individuals with ADHD and comorbid anxiety and/or depression that were female appeared to increase with age, which is consistent with the notion that despite ADHD predominantly affecting male individuals at younger ages, the gender ratio tends to be more similar among adults, which may be due to treatment-seeking behaviors and/or gender-specific effects over the ADHD course [23, 24]. One study has also found that the prevalence of certain ADHD psychiatric comorbidities, including anxiety and depression, was significantly higher among adult women than men [25], which may also help to explain the results seen in the current study. The presence of the comorbidity profile was associated with frequent changes in ADHD pharmacological treatment, with over 60% of patients having a treatment change within 12 months of initiating their ADHD medications, and their likelihood of experiencing a treatment change was 20–40% higher than those without the comorbidity profile. Additionally, a greater number of treatment changes generally translated to higher total direct healthcare costs. Together, these findings suggest that under the current ADHD treatment landscape, patients with ADHD and comorbid anxiety and/or depression tend to be more challenging to manage and could bear a higher burden than those with ADHD alone; thus, strategies to optimize management for this patient population are warranted.

Treatment pattern studies among the overall population of child, adolescent, and adult patients with ADHD using the same database have been previously conducted [19, 20]. Several observations have emerged when comparing the current findings with those in the overall ADHD population. Regarding the first ADHD pharmacological treatment observed, it is noted that although stimulants were the most prevalent initial treatment across populations, patients in the current study who had anxiety and/or depression were more likely to receive a non-stimulant and less likely to receive a stimulant as their first treatment regimen compared to the overall population. Importantly, compared with the overall population of patients with ADHD, those who had ADHD and comorbid anxiety and/or depression appeared to experience more frequent changes in ADHD pharmacological treatment and generally incur higher excess costs by treatment change. For instance, the proportions of patients with ADHD who had a treatment change within 12 months were approximately 5–25% higher among those with anxiety and/or depression than the overall ADHD population across age groups. Relative to patients without a treatment change, the excess adjusted annual direct healthcare costs incurred by patients with three treatment changes were approximately 40–220% higher among those with anxiety and/or depression than the overall population across age groups. The current study thus extended previous findings by demonstrating that the subgroup of patients with ADHD and comorbid anxiety and/or depression incurred a more substantial clinical and economic burden than the overall ADHD population.

The added burden among patients with ADHD and a comorbidity profile may link to their more complex diagnosis and management [9, 12]. Accurate differential diagnosis can be challenging owing to the overlap** clinical features between ADHD and common psychiatric comorbidities such as anxiety and depression [9, 13, 14]. It may also be difficult to determine if ADHD is driving the anxiety/depressive symptoms or if ADHD coexists with a distinct anxiety/depressive disorder, which may require different treatments and management approaches [16, 23, 26]. Therefore, without a confirmed etiology of the symptoms, trial and error in medications may be required. While additional medications may be used to control the comorbidities, they may increase the risk of new complications and add to the costs. Furthermore, patients with ADHD and comorbidities may exhibit more severe ADHD symptoms and have a higher likelihood of develo** additional psychiatric comorbidities than those with ADHD alone [15,16,17]; notably, suboptimal symptom management has been reported to be a leading reason for treatment changes in ADHD [19, 20]. Hence, comorbidities may complicate multiple aspects of ADHD care, adding excess burden to patients and clinicians.

The current results showed that the pharmacological treatment patterns of ADHD with or without comorbid anxiety and/or depression differed, suggesting that these comorbidities must be taken into account when formulating treatment strategies. Current consensus in guidelines and the literature for treating patients presenting with ADHD and comorbidities is to first treat the most severe and functionally impairing symptoms, followed by the residual ADHD or comorbid symptoms in a stepwise manner after the patient has responded to treatment [12, 26, 27]. Potential avenues to mitigate the burden associated with ADHD and comorbidities may include the use of more efficacious therapies that may target both core ADHD and comorbid symptoms [23] as well as psychosocial interventions to improve current and long-term patient functioning (e.g., behavioral and social functioning) [12, 27].

The findings of this study should be interpreted in light of certain limitations. The study included a commercially insured population with ADHD in the USA, and thus the results may not be representative of the general ADHD population or patients outside of the US healthcare system. As a result of the requirement of 18 months of continuous health plan enrollment, the findings may not be representative of patients with less stable insurance. The results may also be subject to underreporting of comorbidities and general billing inaccuracies and missing data in claims. Furthermore, as patients were captured along different trajectories of their treatment journey, it was not possible to confirm whether the first observed treatment was the first treatment received after the diagnosis of ADHD; thus, a mixed population of patients with different treatment history could have been included.

Conclusions

In this large-scale retrospective analysis, comorbid anxiety and/or depression was found to be common among patients with ADHD with prevalence increasing with age. Patients with ADHD and comorbid anxiety and/or depression were significantly more likely to experience a change in ADHD pharmacological treatment than those without these psychiatric comorbidities. Furthermore, the number of treatment changes displayed a positive relationship with total excess annual direct healthcare costs. Efforts to mitigate the burden associated with ADHD and comorbidities are warranted.

References

Sibley MH, Arnold LE, Swanson JM, et al. Variable patterns of remission from ADHD in the multimodal treatment study of ADHD. Am J Psychiatry. 2022;179(2):142–51.

Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. 2018 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) data query. Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health supported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB). www.childhealthdata.org. Accessed 26 Feb 2020.

Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):716–23.

Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ, et al. Prevalence, persistence, and sociodemographic correlates of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(4):372–80.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2013.

Schein J, Adler LA, Childress A, et al. Economic burden of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among children and adolescents in the United States: a societal perspective. J Med Econ. 2022;25(1):193–205.

Schein J, Adler LA, Childress A, et al. Economic burden of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among adults in the United States: a societal perspective. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2022;28(2):168–79.

Jensen PS, Hinshaw SP, Kraemer HC, et al. ADHD comorbidity findings from the MTA study: comparing comorbid subgroups. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(2):147–58.

Katzman MA, Bilkey TS, Chokka PR, Fallu A, Klassen LJ. Adult ADHD and comorbid disorders: clinical implications of a dimensional approach. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):302.

Mak ADP, Lee S, Sampson NA, et al. ADHD comorbidity structure and impairment: results of the WHO World Mental Health Surveys International College Student Project (WMH-ICS). J Atten Disord. 2022;26(8):1078–96.

Gnanavel S, Sharma P, Kaushal P, Hussain S. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and comorbidity: a review of literature. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7(17):2420–6.

Barbaresi WJ, Campbell L, Diekroger EA, et al. Society for Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics clinical practice guideline for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with complex attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2020;41(Suppl 2S):S35–57.

Newcorn JH, Weiss M, Stein MA. The complexity of ADHD: diagnosis and treatment of the adult patient with comorbidities. CNS Spectr. 2007;12(8 Suppl 12):1–16.

Burgic-Radmanovic M, Burgic S. Comorbidity in children and adolescents with ADHD. 2020. In: Kumperscak HG, editor. ADHD—from etiology to comorbidity. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.94527 .

Bowen R, Chavira DA, Bailey K, Stein MT, Stein MB. Nature of anxiety comorbid with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children from a pediatric primary care setting. Psychiatry Res. 2008;157(1–3):201–9.

D’Agati E, Curatolo P, Mazzone L. Comorbidity between ADHD and anxiety disorders across the lifespan. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2019;23(4):238–44.

McIntyre RS, Kennedy SH, Soczynska JK, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults with bipolar disorder or major depressive disorder: results from the international mood disorders collaborative project. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(3):PCC.09m00861.

Wolraich ML, Hagan JF Jr, Allan C, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2019;144(4):e20192528.

Schein J, Childress A, Adams J, et al. Treatment patterns among adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the United States: a retrospective claims study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(11):2007–14.

Schein J, Childress A, Adams J, et al. Treatment patterns among children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the United States - a retrospective claims analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22(1):555.

Kessler RC, Adler LA, Barkley R, et al. Patterns and predictors of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder persistence into adulthood: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57(11):1442–51.

Larson K, Russ SA, Kahn RS, Halfon N. Patterns of comorbidity, functioning, and service use for US children with ADHD, 2007. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):462–70.

Faraone SV. The pharmacology of amphetamine and methylphenidate: relevance to the neurobiology of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and other psychiatric comorbidities. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018;87:255–70.

Matte B, Anselmi L, Salum GA, et al. ADHD in DSM-5: a field trial in a large, representative sample of 18- to 19-year-old adults. Psychol Med. 2015;45(2):361–73.

Solberg BS, Halmoy A, Engeland A, Igland J, Haavik J, Klungsoyr K. Gender differences in psychiatric comorbidity: a population-based study of 40 000 adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;137(3):176–86.

Canadian ADHD Resource Alliance (CADDRA). Canadian ADHD Practice Guidelines. 4th ed. Toronto: CADDRA; 2018.

McIntosh D, Kutcher S, Binder C, Levitt A, Fallu A, Rosenbluth M. Adult ADHD and comorbid depression: a consensus-derived diagnostic algorithm for ADHD. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2009;5:137–50.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study was supported by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. The sponsor also funded the journal’s rapid service fee.

Medical Writing and/or Editorial Assistance

Medical writing assistance was provided by Flora Chik, PhD, MWC an employee of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc.

Author Contributions

Patrick Gagnon-Sanschagrin, Jessica Maitland, Jerome Bedard, Martin Cloutier, and Annie Guérin contributed to study conception and design, collection and assembly of data, and data analysis and interpretation. Jeff Schein and Ann Childress contributed to study conception and design, data analysis and interpretation. All authors reviewed and approved the final content of this manuscript.

Prior Presentation

Part of the material in this manuscript was presented at Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMCP) Nexus 2022, October 11–14, 2022, in National Harbor, MD, as a poster presentation.

Disclosures

Jeff Schein is an employee of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. Ann Childress received research support from Allergan, Takeda/Shire, Emalex, Akili, Ironshore, Arbor, Aevi Genomic Medicine, Neos Therapeutics, Otsuka, Pfizer, Purdue, Rhodes, Sunovion, Tris, KemPharm, Supernus, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration; was on the advisory board of Takeda/Shire, Akili, Arbor, Cingulate, Ironshore, Neos Therapeutics, Otsuka, Pfizer, Purdue, Adlon, Rhodes, Sunovion, Tris, Supernus, and Corium; received consulting fees from Arbor, Ironshore, Neos Therapeutics, Purdue, Rhodes, Sunovion, Tris, KemPharm, Supernus, Corium, Jazz, Tulex Pharma, and Lumos Pharma; received speaker fees from Takeda/Shire, Arbor, Ironshore, Neos Therapeutics, Pfizer, Tris, and Supernus; and received writing support from Takeda/Shire, Arbor, Ironshore, Neos Therapeutics, Pfizer, Purdue, Rhodes, Sunovion, and Tris. Patrick Gagnon-Sanschagrin, Jessica Maitland, Jerome Bedard, Martin Cloutier, and Annie Guérin are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Data are de-identified and comply with the patient requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Therefore, no institutional review board exemption nor informed consent was required.

Data Availability

The data sets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because they were used pursuant to a data use agreement. Requests for data should be made directly to IBM.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schein, J., Childress, A., Gagnon-Sanschagrin, P. et al. Treatment Patterns Among Patients with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Comorbid Anxiety and/or Depression in the United States: A Retrospective Claims Analysis. Adv Ther 40, 2265–2281 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-023-02458-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-023-02458-5