Abstract

Stroke, a significant neurological condition, often results in stroke survivors who are older adults relying on family caregivers, including children and spouses, leading to increased challenges for caregivers. This study investigates the experiences of family caregivers caring for stroke survivors who are older adults, focusing on the context of stroke management. Participants were purposively sampled, and three focus group discussions involving family caregivers (n = 18) of older adults who had experienced strokes were conducted. Conversations were recorded, translated, transcribed, and subjected to thematic analysis utilizing NVivo (version 12 pro) software. Thematic analysis yielded five distinct themes. The first theme illuminated family caregivers’ insights regarding the management of stroke in their members or significant others. The second theme emphasized the support and information received at the medical facility. The third theme showcased the perceived value of the information provided. The fourth theme highlighted unmet needs for both information and training in social support. The final theme illuminated the participants’ preferences for how they would like to receive information and training. This study highlights family caregivers’ experiences, encompassing a range of burdens, stresses, and challenges while caring for stroke survivors who are older adults. Findings emphasize the necessity for formal caregivers to provide adequate information, support, and training to family caregivers, thereby alleviating their burdens and enhancing stroke management in a home environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Family members have long been involved in caregiving (Schulz et al., 2020). Population ageing, longer lifespans of older adults with significant morbidities, and poorly coordinated health systems have all increased the caregiving burden on family members (Schulz et al., 2020). Caregivers’ expanded role has also resulted from the growing trend of early discharge and treatment (Quinn et al., 2014 ). Stroke caregivers often face difficulties that arise from caregiving for their loved ones who are stroke survivors, and these include stress, burden, and a lower standard of living (Greenwood et al., 2009).

Stroke represents a significant public health concern, standing as a leading contributor to global morbidity and mortality (Lopez & Mathers, 2006). Reports indicate that 70% of all stroke deaths and 87% of disability are attributed to low-income and middle-income countries (Kim et al., 2020; Owolabi et al., 2015). Notably, African nations, including Nigeria, have observed a rising prevalence of stroke (Adeloye, 2014). Nigeria has a crude incidence of 27.4 per 100,000 in a year and a 30-day case fatality rate as high as 40% (Adigwe et al., 2022). This is expected to increase as the population ages. Stroke often places survivors in a position of dependency on family caregivers (Vincent-Onabajo et al., 2018). In the absence of adequate post-discharge management, the responsibility of caring for stroke survivors frequently falls on family members and close associates (Bragstad et al., 2014). Reintegration into home life after a stroke presents a formidable challenge for patients, who must adapt to altered life circumstances marked by physical limitations, stress, depression, cognitive decline, and diminished quality of life (Cerniauskaite et al., 2012).

There is a growing understanding of the value of family involvement in patient outcomes and the significance of holistic care for patients undergoing stroke recovery (Loupis & Faux, 2013). Gaining a profound comprehension of individuals’ encounters with stroke can offer insight into the unmet needs and challenges faced by caregivers (Bulley et al., 2010). Despite prior experience in caring for those with chronic illnesses, the demands and vigilance required of family caregivers to ensure adequate home-based care can prove overwhelming and draining (Lutz et al., 2011). Due to weighty responsibilities, uncertainties, anxieties, and curtailed social lives, informal caregiving has been identified as a burden culminating in physical and psychological strain, along with decreased quality of life for caregivers ( Gillespie & Campbell, 2011; Greenwood et al., 2009).

Several scholars in Nigeria have directed their attention towards quantitatively assessing the quality of life and burden experienced by caregivers of stroke patients (Abdullahi et al., 2022; Akosile et al., 2011, 2016) and there are documented high levels of caregiver strain, negative caregiver experience, and very low social support (Akosile et al., 2018; Okoye et al., 2019; Vincent-Onabajo et al., 2018) with little or no information on the lived experiences of family caregivers of stroke survivors who are older adults. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study employing a qualitative approach to gain in-depth insight from the target population in Nigeria. This we believe will bring about a comprehensive understanding of family caregivers’ lived experiences throughout the stroke care continuum and ultimately guide future interventions and policy formulation on a holistic approach to stroke care of the older adults. The central objective of this study was to explore the lived experience of family caregivers in the management of stroke in older adults in Nigeria.

Methodology

A cross-sectional qualitative design was employed to address the objective of this study.

Study setting and participants

Family caregivers of stroke survivors who are older adults were recruited through outpatient case notes from the geriatric centre and neurology clinic in University College Hospital, a tertiary facility in Southwestern Nigeria, following ethical approval and permission from authorities. Inclusion criteria required participants to be in-dwelling caregivers actively involved in home-based care of the stroke survivors who are older adults, stroke patients in this context should be at least 60 years old and should have been previously diagnosed with acute, focal neurological deficit as a result of vascular injury to the central nervous system with a neuroimaging evidence of infarct or hemorrhage (Murphy SJx & Werring DJ., 2020), caregivers must be aged 18 years and above, and willing to participate. Exclusion criteria involved the denial of potential participants to provide informed consent. Purposive sampling was used and a total of eighteen family caregivers participated in the focus group discussion.

Data collection procedure

Focus group discussion was used to facilitate conversation with participants as it can elicit extensive information on the subject matter (O. Nyumba T, Wilson K, Derrick CJ & Mukherjee N., 2018). Three focus group discussions were conducted, with two groups consisting of female family caregivers and the third group consisting of only male caregivers, each group comprising six participants. The interviews were conducted in a lounge with a comfortable seating arrangement at Adebutu Kesington Geriatric Rehabilitation Centre, University College Hospital, Ibadan. Informed consent and sociodemographic information were obtained before the discussion, covering age, gender, educational qualification, religion, ethnicity, marital status, relationship with patients, duration of care, and patient age. A semi-structured interview guide (supplementary file 1) containing open-ended questions was used to elicit enough information from the participants. The questions asked were informed by a literature review. The interview guide contained the main questions and probes. Participants were informed about audio recording and ground rules. Interviews lasted approximately 60 min and were conducted in February 2023.

Data analysis

Audiotapes were translated and transcribed, with researchers ensuring data quality and accuracy. Transcriptions were anonymized and underwent further validation, correcting errors and combining fragmented issues. The researcher and a team of three experienced qualitative researchers conducted the analysis. NVivo 12 software facilitated coding, sub-coding, categorization, and theme identification, employing an inductive-dominant approach. The methods used for data analysis included creating resources, using nodes to code, and running queries to provide findings that allowed theories to be verified and developed. Codes and specimens generated were checked carefully for review and critique by the researcher and the team. Disagreements were resolved among them by reaching a consensus on any conflict before proceeding to the next phase. Common and peculiar trends, as well as similar and divergent opinions, were noted. Findings were summarized, and relevant verbatim quotes were provided.

Ethical consideration.

Ethical approval was obtained from the College of Nursing, Midwifery, and Health research ethics panel (No.1325) at the University of West London and the University of Ibadan/ University College Hospital Ethics Committee (No. UI/EC/22/0410). Verbal and written informed consent were obtained, with participants informed of their right to withdraw. Anonymity was ensured through assigned identity numbers, and strict confidentiality and privacy were maintained throughout the study.

Results

Eighteen participants with a mean age of 42.94 ± 12.04 years were included in the study. The majority (66.7%) were females, aged between 35 and 59 years, 77.8% were married, and 88.9% were of Yoruba ethnicity (Table 1).

Emergent themes across all participant groups.

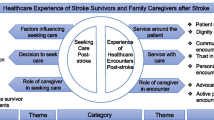

Analysis of interview data revealed five distinct themes representing the experiences of family caregivers of stroke survivors who are older adults.

Experiences in managing stroke-afflicted family members/significant others:

-

Challenges Faced by Female Participants:

Many female participants in the focus group discussion highlighted the difficulties they encountered while assisting hospitalized family members with daily tasks like eating, bathing, and using the restroom. Financial strain emerged. Is a recurrent issue due to the need for various medications and frequent tests. Participants expressed distress over the constant financial burden associated with procuring medicines and undergoing tests. A participant emphasized the challenges: "The experience I have involves issues with money and relentless pursuit of acquiring medications. We often lack enough money to buy certain medications. Another aspect involves the rotation of different doctors attending to the patients during the hospital stay. Different doctors prescribe medications, demanding further tests, making it challenging to manage expenses.”

-

Challenges Faced by Male Participants:

Male participants echoed similar financial challenges and stressors related to the hospitalization of family members due to stroke. They also noted behavioural shifts and mood swings in the affected individuals, including increased irritability and reduced ability to perform tasks. A participant expressed the challenges faced: “My experience is undoubtedly challenging, especially the considerable stress within the hospital setting. The lack of basic amenities such as water makes it hard for me. I had to descend to the ground floor to fetch water for cleaning at the hospital.”

-

Home Treatment and Positive Aspects:

A smaller subset mentioned that their stroke-affected family members received treatment at home under a doctor’s care and utilized massage equipment. Some participants highlighted positive aspects, including the importance of balanced dietary intake, regular exercise, and adherence to prescribed medications.

Information and support received at the facility:

Insight from female focus group discussion participants shed light on the information and support received at the healthcare facility. Most articulated receiving guidance on dietary preferences for stroke patients, emphasizing the avoidance of sugary and processed foods. Additionally, recommendations for supervised walking sessions to promote mobility were highlighted. However, some participants expressed that the information during visits focused primarily on tests and adhering to prescribed medications. One participant recounted her experience, revealing challenges and financial strains associated with medical procedures and medication procurement. In contrast, two participants mentioned not receiving any information. One anticipated guidance related to the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS), while another received assistance through reduced admission fees, complimentary medications, and massage therapy. The proactive approach of seeking information questioning was emphasized.

Male participants conveyed receiving various forms of information at the healthcare facility, including adherence to prescribed medications, dietary choices, stress reduction, and patient exercises. The transformative effect of this guidance was highlighted, leading to a shift in perceptions and stroke.

-

Usefulness of the information:

Participants overwhelmingly expressed the usefulness of the information received. Many credited following the guidelines for tangible improvements in the patient’s condition. Positive changes were noted in family members’ health, with a shift in perception about stroke leading to the adoption of beneficial practices. A participant highlighted the transformative effect of this guidance:

"The information helped us because we initially thought it was a spiritual problem and we were contemplating traditional remedies until the medical expert clarified that it was a stroke and could be addressed through exercises. This revelation prompted us to embrace exercises earnestly.”

-

Unmet information and Social Support Needs:

Several female participants voiced unmet needs for information and training, particularly regarding post-stroke complications. Dissatisfaction with the physiotherapy services and the desire for comprehensive drug usage guidance were highlighted among male participants. They expressed a need for awareness of potential side effects and the expected duration of recovery. One of the participants elucidated her expectations:

"What I hoped to gain here is the insight into the eye treatment we initially sought. My father had glaucoma, and we were directed to the general outpatient department for his health evaluation. Following consultation with the doctor, we were referred to the geriatric unit, where several tests were prescribed and conducted. However, my anticipation was for the doctor to expound on the test results, elucidate my father’s condition, and provide a comprehensive understanding. Instead, the doctor merely collected the test results, prescribed medications, and assigned the next appointment.”

One participant emphasized the disparity between medical practitioners’ efforts and the insights captured in medical literature. Beyond the hospital environment, participants sought guidance on machines and practices to aid recovery. The uncertainty surrounding medication continuity prompted attendance at the session to seek clarity. One participant elucidated this perspective:

"Notably, the medical practitioners are indeed making efforts, but their delivery falls short of the insight captured in the medical literature. Those outside with the experience of the illness know what the patient will use for them to recover. Like in the hospital now, there are physiotherapy resources; however, certain critical details are occasionally left unaddressed. Beyond the hospital environment, those with experience will tell us the kind of machines and things we should buy, and it is hel** the patient. Another thing is doctors prescribe drugs for us; I don't understand how the patient will be using it for life or if it has a stopover for some time, and maybe some drugs will be added or removed. The uncertainty prompts me to attend this session today, seeking clarity on the continuity of the medication”.

The preferred manner of receiving information and training:

The majority of female participants expressed a strong willingness to receive comprehensive training and information related to stroke and its management. One participant explicitly stated her openness to learning from stroke experts, expressing a desire for more insights into the disease, particularly given her mother’s absence of high blood pressure:

"I am wholeheartedly open to receiving such training. Stroke experts can lecture us to learn more about the disease. What baffled me is that my mother does not have high blood pressure. After all, I've heard that someone with high blood pressure can easily develop a stroke. Her recent blood pressure readings were 100 and 110. She has never nursed high blood pressure or diabetes.”

Both male and female participants expressed enthusiasm for participating in training programs aimed at aiding their family member’s recovery. One participant emphasized the need to comprehend the ailment and methods to prevent potential recurrences. A few male participants suggested that prior notice, ideally three to four days before training, would facilitate their participation. However, some participants shared that if essential information is provided when needed, formal training might not be essential. One participant advocated for more accessible consultations by augmenting the number of available doctors:

"Having more doctors accessible for consultations would be advantageous. This way, ample time could be allocated to addressing queries and concerns."

Discussion

Our study revealed a preponderance of female family caregivers in 12 out of 18 of the participants This finding is similar to several studies which reported a higher percentage of female family caregivers (Hesamzadeh et al., 2017; Menon et al., 2017; Saban & Hogan, 2012; Tseng et al., 2015). This may be a result of a belief system that places the burden of caregiving of family members on the female gender (Akpınar et al., 2011; del-Pino-Casado et al., 2012). Female caregivers are likely to combine stroke caregiving with domestic activities and job demands which could result in increased stress and burden (Menon et al., 2017; Vincent-Onabajo et al., 2018). These hurt their financial strength and purchasing power which may result in financial dependence and low self-esteem. Therefore, a formulation of policy that provides favourable socioeconomic inclusion of female caregivers, educational empowerment, and paid time for service provided are important to improve caregiver and stroke survivors’ quality of life.

The identification of five key themes, covering stroke management, information, and support reception, utilization of provided information, unmet information, and training delivery, provides valuable insights into the multifaceted challenges within the caregiving domain.

The narratives from our study participants underscore the substantial role played by family caregivers in assisting stroke-affected individuals with their daily living activities which often lead to significant burdens. This is similar to existing literature that highlights the demands and stress placed upon informal family caregivers in stroke scenarios as a considerable proportion (25 -75%) require assistance for daily activities from family caregivers (Bhattacharjee et al., 2012; Costa et al., 2015; Danzl et al., 2013). This emphasizes the pivotal role these caregivers play (Kalra et al., 2004). Our study resonates with prior research, exemplified by Jika et al., (Jika et al., 2021), which illuminated the physical, financial, and psychological strains endured by family caregivers in a similar context. Several studies carried out in different geographical regions in Nigeria highlighted high levels of caregiver strain as a result of a lack of social support and strain on family income (Akosile et al., 2018; Vincent-Onabajo et al., 2018). Additionally, studies conducted in different countries including Denmark and Italy gave an exposition on the caregivers’ emotional tolls emanating from difficult communication and memory deficits with stroke survivors (Bakas et al., 2006; Kitzmüller et al., 2012; Pallesen, 2014; Simeone et al., 2015). Similarly, a study conducted in Brazil revealed detrimental changes in different domains such as overall quality of life, physical, emotional, social, and environmental of family caregivers of stroke survivors (Caro et al., 2018). This indicates that family caregivers of stroke survivors across various parts of the world undergo similar burdens and experiences. Hence personalized interventions focusing on improved overall quality of life are needed to reduce the associated stress of caring for stroke survivors who are older adults.

Financial concerns emerge as a salient issue, with participants expressing varying perspectives, ranging from support such as subsidised admission fees and free medication, to unmet expectations, such as the absence of the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) provision. Out-of-pocket payment is a major challenge in Nigeria as health insurance is limited to only 5% of which the majority are government employees. This has made individuals and families incur catastrophic expenses further impoverishing them because of their health challenges (Aregbeshola, 2016). This aligns with findings by Gott et al., (Gott et al., 2015) underscoring the financial strain endured by family caregivers due to the direct and indirect costs of care, significantly impacting both the quality of care received by patients and the well-being of caregivers. Providing a comprehensive support system, including financial assistance and health counselling, becomes imperative for mitigating these challenges (Denham et al., 2019). The healthcare system in Nigeria is still largely underdeveloped with poor facilities and inadequate staffing of skilled personnel especially in the rural area (Musa, 2021). Our study was carried out in the urban centre of Ibadan, Oyo State in one of the leading teaching Hospitals in Nigeria, University College Hospital. The care received by the patients and their family caregivers while on admission and after admission is suboptimal as expressed by our participants. However, the scope of our study is limited to the experiences of stroke survivors and their respective family caregivers. It is imperative to explore the institutional or health system capacity in stroke management.

The need for general information support was highlighted by our study participants as it reveals gaps in knowledge of stroke and its management. A noteworthy finding is the perception of stroke as a spiritual affliction by one of our study participants which could hurt the care of stroke survivors who are older adults. Recognizing the importance of providing accurate information and support for effective stroke management is paramount (Cecil et al., 2013). Hence collaboration between formal carers and family caregivers is a crucial support system, offering valuable insights and knowledge that positively impacts stroke management. A study by Mackenzie et al. (Mackenzie et al., 2007) reveals caregiver strain during the active phase of stroke prompting active seeking of essential information. This underscores the pivotal role of coordinated efforts between formal and family caregivers in enhancing the understanding and implementation of appropriate care practices (Cameron et al., 2013; Creasy et al., 2013).

While the study shed light on the information and support landscape, it also underscores existing gaps. A prevailing unmet need for specific information and social support training is evident, encompassing areas such as stroke awareness, seizure management, physiotherapy approaches, and the interpretation of diagnostic test results. The importance of appropriate information and support has been identified especially during the early stages of stroke incidence (Cecil et al., 2013).

This underscores the significance of bridging these knowledge gaps, as an informed caregiver is better equipped to provide optimal care and address survivors’ needs (Creasy et al., 2013; Mackenzie et al., 2007; Wagachchige Muthucumarana et al.,2018). Caregivers’ enthusiasm for knowledge acquisition does not always align with the successful fulfilment (Creasy et al., 2013), emphasizing the need for effective communication and tailored educational interventions.

Overall, our study underpinned the complex interplay between caregiving challenges, information dissemination, and support dynamics. This study not only offers valuable insights into the existing landscape but also highlights the critical need for targeted interventions that encompass comprehensive support, knowledge enhancement, and effective coordination between formal and family caregivers. By addressing these dimensions, the study has the potential to significantly enhance stroke management outcomes and alleviate the burdens borne by both caregivers and patients in Nigeria.

Conclusion

Beyond formal caregivers, family caregivers emerge as pivotal stakeholders significantly contributing to stroke management and its associated complexities. This study provides a profound understanding of family caregivers’ encounters in the realm of stroke management in Nigeria. Their journey is marked by a continuum of burdens, anxieties, and challenges arising from tending to stroke-affected older adults during their recovery. Importantly, the study reveals an eagerness among informal caregivers to acquire enhanced knowledge concerning stroke prevention and effective management of its repercussions. Considering these findings, it becomes imperative for formal caregivers to extend substantial support and comprehensive training to family caregivers. Such interventions should ideally commence during the acute care phase at the hospital and persist into the post-discharge period. This proactive approach holds the potential to alleviate caregiver strain, enhance the quality of home-based stroke management, and subsequently contribute to more favourable patient outcomes.

Strengths and Limitations of Study

The strength of this study is rooted in its thorough exploration of the experiences encountered by family caregivers attending to stroke-affected older adults in Nigeria. Our sample size was considerably adequate for the methodology employed. However, this study, conducted within the southwestern region of Nigeria, may have limitations concerning its generalizability to other geographical areas within the country. Additionally, it is acknowledged that recall bias might be inevitable, considering the reliance on participants’ subjective recollections as the basis for the study’s findings and translation of local languages to English. Purposive sampling employed could introduce selection bias thereby eliminating potential participants. The preponderance of female participants could have limited gaining extensive insight into male experience in stroke caregiving to older adults.

References

Abdullahi, A., Aliyu, K., Hassan, A. B., Sokunbi, G. O., Bello, B., Saeys, W., et al. (2022). Prevalence of chronic non-specific low back pain among caregivers of stroke survivors in Kano, Nigeria and factors associated with it: A cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Neurology, 5(13), 900308.

Adeloye, D. (2014). An estimate of the incidence and prevalence of stroke in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One, 9(6), e100724.

Adigwe, G. A., Tribe, R., Alloh, F., & Smith, P. (2022). The Impact of Stroke on the Quality of Life (QOL) of Stroke Survivors in the Southeast (SE) Communities of Nigeria: A Qualitative Study. Disabilities., 2(3), 501–515.

Akosile, C. O., Okoye, E. C., Nwankwo, M. J., Akosile, C. O., & Mbada, C. E. (2011). Quality of life and its correlates in caregivers of stroke survivors from a Nigerian population. Quality of Life Research, 20(9), 1379–1384.

Akosile, C. O., Okoye, E. C., Adegoke, B. O. A., Mbada, C. E., Maruf, F. A. & Okeke, I. A. (2016). Burden, health and quality of life of Nigerian stroke caregivers. Health Care Current Reviews, 1(1), 105.

Akosile, C. O., Banjo, T. O., Okoye, E. C., Ibikunle, P. O., & Odole, A. C. (2018). Informal caregiving burden and perceived social support in an acute stroke care facility. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 16(1), 57.

Akpınar, B., Küçükgüçlü, Ö., & Yener, G. (2011). Effects of gender on burden among caregivers of Alzheimer’s patients. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 43(3), 248–254.

Aregbeshola, B. S. (2016). Out-of-pocket payments in Nigeria. The Lancet, 387(10037), 2506.

Bakas, T., Kroenke, K., Plue, L. D., Perkins, S. M., & Williams, L. S. (2006). Outcomes Among Family Caregivers of Aphasic Versus Nonaphasic Stroke Survivors. Rehabilitation Nursing., 31(1), 33–42.

Bhattacharjee, M., Vairale, J., Gawali, K., & Dalal, P. (2012). Factors affecting burden on caregivers of stroke survivors: Population-based study in Mumbai (India). Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology, 15(2), 113.

Bragstad, L. K., Kirkevold, M., & Foss, C. (2014). The indispensable intermediaries: A qualitative study of informal caregivers’ struggle to achieve influence at and after hospital discharge. BMC Health Services Research, 14(1), 331.

Bulley, C., Shiels, J., Wilkie, K., & Salisbury, L. (2010). Carer experiences of life after stroke – a qualitative analysis. Disability and Rehabilitation., 32(17), 1406–1413.

Cameron, J. I., Naglie, G., Silver, F. L., & Gignac, M. A. M. (2013). Stroke family caregivers’ support needs change across the care continuum: A qualitative study using the timing it right framework. Disability and Rehabilitation., 35(4), 315–324.

Caro, C. C., Costa, J. D., & Da Cruz, D. M. C. (2018). Burden and Quality of Life of Family Caregivers of Stroke Patients. Occupational Therapy in Health Care., 32(2), 154–171.

Cecil, R., Thompson, K., Parahoo, K., & McCaughan, E. (2013). Towards an understanding of the lives of families affected by stroke: A qualitative study of home carers. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 69(8), 1761–1770.

Cerniauskaite, M., Quintas, R., Koutsogeorgou, E., Meucci, P., Sattin, D., Leonardi, M., et al. (2012). Quality-of-Life and Disability in Patients with Stroke. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation., 91(13), S39-47.

Costa TFD, Costa KNDFM, Martins KP, Fernandes MDGDM, Brito SDS. Burden over family caregivers of elderly people with stroke. Escola Anna Nery - Revista de Enfermagem [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2023 Aug 30];19(2). Available from: https://doi.org/10.5935/1414-8145.20150048

Creasy, K. R., Lutz, B. J., Young, M. E., Ford, A., & Martz, C. (2013). The Impact of Interactions with Providers on Stroke Caregivers’ Needs. Rehabilitation Nursing., 38(2), 88–98.

Danzl, M. M., Hunter, E. G., Campbell, S., Sylvia, V., Kuperstein, J., Maddy, K., et al. (2013). “Living With a Ball and Chain”: The Experience of Stroke for Individuals and Their Caregivers in Rural Appalachian Kentucky: Stroke in Rural Appalachian Kentucky. The Journal of Rural Health., 29(4), 368–382.

del‐Pino‐Casado R, Frías‐Osuna A, Palomino‐Moral PA, Ramón Martínez‐Riera J. Gender Differences Regarding Informal Caregivers of Older People. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2012 44(4):349–57

Denham AMJ, Wynne O, Baker AL, Spratt NJ, Turner A, Magin P, et al. (2019) “This is our life now. Our new normal”: A qualitative study of the unmet needs of carers of stroke survivors. Weiland T, editor. PLoS ONE. 2019 ;14(5):e0216682.

Gillespie, D., & Campbell, F. (2011). Effect of stroke on family carers and family relationships. Nursing Standard., 26(2), 39–46.

Gott, M., Allen, R., Moeke-Maxwell, T., Gardiner, C., & Robinson, J. (2015). ‘No matter what the cost’: A qualitative study of the financial costs faced by family and whānau caregivers within a palliative care context. Palliative Medicine, 29(6), 518–528.

Greenwood, N., Mackenzie, A., Cloud, G. C., & Wilson, N. (2009). Informal primary carers of stroke survivors living at home–challenges, satisfactions and co**: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Disability and Rehabilitation., 31(5), 337–351.

Hesamzadeh, A., Dalvandi, A., BagherMaddah, S., FallahiKhoshknab, M., Ahmadi, F., & Mosavi, A. N. (2017). Family caregivers’ experience of activities of daily living handling in older adult with stroke: A qualitative research in the Iranian context. Scandinavian Caring Sciences., 31(3), 515–526.

Jika, B. M., Khan, H. T. A., & Lawal, M. (2021). Exploring experiences of family caregivers for older adults with chronic illness: A sco** review. Geriatric Nursing., 42(6), 1525–1532.

Kalra, L., Evans, A., Perez, I., Melbourn, A., Patel, A., Knapp, M., et al. (2004). Training carers of stroke patients: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ, 328(7448), 1099.

Kim, J., Thayabaranathan, T., Donnan, G. A., Howard, G., Howard, V. J., Rothwell, P. M., et al. (2020). Global Stroke Statistics 2019. International Journal of Stroke., 15(8), 819–838.

Kitzmüller, G., Asplund, K., & Häggström, T. (2012). The Long-Term Experience of Family Life After Stroke. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing., 44(1), E1-13.

Lopez, A. D., & Mathers, C. D. (2006). Measuring the global burden of disease and epidemiological transitions: 2002–2030. Annals of Tropical Medicine & Parasitology., 100(5–6), 481–499.

Loupis, Y. M., & Faux, S. G. (2013). Family Conferences in Stroke Rehabilitation: A Literature Review. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases., 22(6), 883–893.

Lutz, B. J., Ellen Young, M., Cox, K. J., Martz, C., & Rae, C. K. (2011). The Crisis of Stroke: Experiences of Patients and Their Family Caregivers. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation., 18(6), 786–797.

Mackenzie, A., Perry, L., Lockhart, E., Cottee, M., Cloud, G., & Mann, H. (2007). Family carers of stroke survivors: Needs, knowledge, satisfaction and competence in caring. Disability and Rehabilitation., 29(2), 111–121.

Menon, B., Salini, P., Habeeba, K., Conjeevaram, J., & Munisusmitha, K. (2017). Female caregivers and stroke severity determines caregiver stress in stroke patients. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology, 20(4), 418.

Murphy SJx, Werring DJ. Stroke: causes and clinical features. Medicine. 2020;48(9):561–6.

Musa, M. J. (2021). An assessment of healthcare facilities in some selected slum areas of Minna, Niger State (Doctoral dissertation).

O.Nyumba T, Wilson K, Derrick CJ, Mukherjee N. (2018).The use of focus group discussion methodology: Insights from two decades of application in conservation. Geneletti D, editor. Methods in Ecology and Evolution. 9(1):20–32.

Okoye, E. C., Okoro, S. C., Akosile, C. O., Onwuakagba, I. U., Ihegihu, E. Y., & Ihegihu, C. C. (2019). Informal caregivers’ well-being and care recipients’ quality of life and community reintegration – findings from a stroke survivor sample. Scandinavian Caring Sciences., 33(3), 641–650.

Owolabi, M., Akarolo-Anthony, S., Akinyemi, R., Arnett, D., Gebregziabher, M., Jenkins, C., et al. (2015). The burden of stroke in Africa: A glance at the present and a glimpse into the future: Review article. CVJA., 26(2), S27-38.

Pallesen H. Body, co** and self-identity. (2014). A qualitative 5-year follow-up study of stroke. Disability and Rehabilitation. 36(3):232–41.

Quinn, K., Murray, C., & Malone, C. (2014). Spousal experiences of co** with and adapting to caregiving for a partner who has a stroke: A meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Disability and Rehabilitation., 36(3), 185–198.

Saban, K. L., & Hogan, N. S. (2012). Female Caregivers of Stroke Survivors: Co** and Adapting to a Life That Once Was. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing., 44(1), 2–14.

Schulz, R., Beach, S. R., Czaja, S. J., Martire, L. M., & Monin, J. K. (2020). Family Caregiving for Older Adults. Annual Review of Psychology, 71(1), 635–659.

Simeone, S., Savini, S., Cohen, M. Z., Alvaro, R., & Vellone, E. (2015). The experience of stroke survivors three months after being discharged home: A phenomenological investigation. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 14(2), 162–169.

Tseng CN, Huang GS, Yu PJ, Lou MF. (2015).A Qualitative Study of Family Caregiver Experiences of Managing Incontinence in Stroke Survivors. Dalal K, editor. PLoS ONE. 10(6):e0129540.

Vincent-Onabajo, G., PutoGayus, P., Masta, M. A., Ali, M. U., Gujba, F. K., Modu, A., et al. (2018). Caregiving Appraisal by Family Caregivers of Stroke Survivors in Nigeria. Journal of Caring Sciences, 7(4), 183–188.

WagachchigeMuthucumarana, M., Samarasinghe, K., & Elgán, C. (2018). Caring for stroke survivors: Experiences of family caregivers in Sri Lanka – a qualitative study. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation., 20, 1–6.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the family caregivers who willingly participated in the study and gave insight into their lived experiences. We would like to thank Ms. Olajoke Akinyemi for her support in ensuring quality data collection and for healthcare providers who assisted in participant recruitment.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors declared no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Farombi, T.H., Khan, H.T.A. & Lawal, M. Exploring the Experiences of Family Caregivers in the Management of Stroke Among the Older Adults in Nigeria: A Qualitative Study. Population Ageing (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12062-024-09454-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12062-024-09454-9