Abstract

This paper shows that the family continues to be an important source of support for the rural elderly, particularly the rural elderly over 70 years of age. Decline in likelihood of co-residence with, or in close proximity to, adult children raises the possibility that China’s rural elderly will receive less support in the forms of both income and in-kind instrumental care. While descriptive evidence on net-financial transfers suggests that elderly with migrant children will receive similar levels of financial transfers as those without migrant children, the predicted variance associated with these transfers implies a higher risk that elderly who have migrant children could fall into poverty. Reducing the risk of low incomes among the elderly is one important motive for new rural pension initiatives supported by China’s government, which are scheduled to be expanded to cover all rural counties by the end of the 12th Five Year Plan in 2016.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For reasons that we will describe in detail in the paper, this should not be interpreted as a causal effect of migration per se, but as a purely descriptive outcome after all welfare maximizing joint migration and transfer decisions have been made.

The vast majority of rural migrants have risky income themselves: they often lack employment contracts, may have seasonal employment of short duration, and lack the workplace protections of formal sector workers.

Using other methods, Cameron and Cobb-Clark (2008) do not find evidence that transfers to parents respond to low parent income in Indonesia.

The dibao is a minimum living standards guarantee program that provides subsidies to households living below a locally determined minimum income threshold. Households are identified for support through community-based targeting.

Selden (1993) concludes that a transition to the nuclear family imposes a heavy price on the rural elderly. Living arrangements are thought to be important for elderly support across East Asia, including Cambodia (Zimmer and Kim, 2002), Thailand (Knodel and Chayovan. 1997), and Vietnam (Anh et al. 1997).

Note that co-residence in rural areas of the four RCRE provinces was also somewhat higher than what we observe for rural areas of the CHNS panel.

Of course, two very different conclusions are consistent with evidence of greater incidence of co-residence with age in a simple cross-section: the oldest, who are more likely to be infirm, tend to move in with adult children; alternatively, if co-residence does have an impact on the quality of care provided, then perhaps only the elderly living with adult children reach old age.

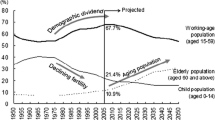

Cai et al. (2009) develop a demographic model that projects the future age structure of rural and urban elderly under alternative fertility and migration rates. Projections in these population pyramids reflect the most-likely of alternatives considered in their paper.

Barro (1974), Becker (1974) and Cox (1987) made important theoretical distinctions highlighting different motives for transfers. Much of the empirical research in the US has suggested that inter-generational inter-vivos transfers are driven by an exchange motives (e.g., Cox and Rank 1992; McGarry 1999) rather than based on altruistic motives. It is important to remember, however, that in the US, the social security safety net provides substantial insurance against poverty in old age, and thus it is not as surprising to find an emphasis on the flow of resources from older to younger generations.

Specifically, we use a bandwidth of 0.25 with observations weighted using a tri-cube weighting function as calculated by the lowess command in Stata. The lowess estimator was developed by Cleveland (1979), and has a benefit over some Kernel estimators in that it does not suffer from bias near the end points.

The Supplemental Rural Household Social Network, Labor Allocation and Land Use Survey was carried out in collaboration with Michigan State University in 2004. Details on the supplemental survey protocol and survey instruments can be found at www.msu.edu/~gilesj/.

A detailed discussion of a larger nine-province sample from the RCRE panel dataset, including discussions of survey protocol, sampling, attrition, and comparisons with other data sources from rural China, can be found in the data appendix of Benjamin et al. (2005). This paper makes use of village and household data from the four provinces where the authors conducted follow-up household and village surveys, which are Shanxi, Jiangsu, Anhui and Henan.

Of course, poverty lines may be somewhat arbitrary, and thus poverty researchers go to considerable lengths to use objective basis on which to develop a poverty line. Summarizing the general approach to estimating a nutrition-based poverty lines, the analyst must first estimate the cost of the underlying food requirements for the basket of foods that might be available for someone near poverty are first estimated. To this cost, costs of other durables and housing for someone near poverty are then added to the nutrition cost, and this value is used to determine the poverty line. Researchers working in the poverty field have thought very carefully about the objective calculation of poverty lines and a useful introduction may be found in Ravallion (1996). We use the nutrition-based poverty line calculated for rural China over the period of the study by Ravallion and Chen (2007), who have long experience working with China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) to develop objective, nutrition-based poverty lines for rural and urban China.

The World Bank Poverty Assessment (Chaudhui and Datt 2009) showed that 65% of rural migrants had lived in the current city where they were working for more than 3 years, and this duration was significantly longer than reported in a similar survey conducted in 2001.

Again, in interpreting these figures, it is important to remember our caveats against interpreting these results in any way as the causal effect of migration. What they provide is descriptive evidence on transfer-responsiveness and transfers to elderly with and without migrant children net of any responses to parent needs for instrumental care or unobservable characteristics related to both parent or child ability, and ability to migrate.

Raising the poverty threshold would imply shifting this line to the northeast, and as evident in Fig. 5, and this would lead to increased risk of falling into poverty. Reducing the threshold would entail shifting this line to the southwest.

In some provinces, the minimum basic pension is as high as 80 RMB per month, or 960 RMB per year.

References

Anh, T. S., Cuong, B. T., Goodkind, D., & Knodel, J. (1997). Living arrangements, patrilinearity and sources of support among elderly Vietnamese. Asia-Pacific Population Journal, 12(4), 69–88.

Barro, R. J. (1974). Are government bonds net wealth? Journal of Political Economy, 82(6), 1095–1117.

Becker, G. (1974). A theory of social interactions. Journal of Political Economy, 82(6), 1063–1093.

Benjamin, D., Brandt, L., & Rozelle, S. (2000). Aging, well-being and social security in Rural North China. Population and Development Review, 26, 89–116.

Benjamin, D., Brandt, L., & Giles, J. (2005). The evolution of income inequality in Rural China. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 53(4), 769–824.

Benjamin, D., Brandt, L., Giles, J., & Wang, S. (2008). Income inequality during China’s economic transition. In L. Brandt and T. Rawski, (Eds.), China’s great economic transformation (Chapter 18). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cai, F., Giles, J., & Meng, X. (2006). How well do children insure parents against low retirement income? An analysis using survey data from Urban China. Journal of Public Economics, 90(12), 2229–2255.

Cai, F., Park, A., & Zhao, Y. (2008). The Chinese labor market. In L. Brandt & T. Rawski (Eds.), China’s great transformation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cai, F., Giles, J., & Wang, D. (2009). The well-being of China’s rural elderly, background paper for East Asia social protection unit, The World Bank (Bei**g).

Cameron, L., & Cobb-Clark, D. (2008). Do Coresidency and financial transfers from the children reduce the need for elderly parents to works in develo** countries? Journal of Population Economics, 21(4), 1007–1033.

Chaudhuri, S., & Datt, G. (2009). From poor areas to poor people: China's evolving poverty agenda, an assessment of poverty and inequality in China, The World Bank.

Cleveland, W. S. (1979). Robust locally weighted regression and smoothing scatterplots. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 74, 829–836.

Cox, D. (1987). Motives for private income transfers. Journal of Political Economy, 95(3), 509–546.

Cox, D., & Rank, M. R. (1992). Inter-vivos transfers and intergenerational exchange. Review of Economics and Statistics, 74(2), 305–314.

Cox, D., Hansen, B. E., & Jimenez, E. (2004). How responsive to private transfers to income? Evidence from a laissez-faire economy. Journal of Public Economics 88.

de Brauw, A., & Giles, J. (2008). Migrant labor markets and the welfare of rural households in the develo** world: evidence from China. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 4585, June 2008.

Duclos, J.-Y., Araar, A., & Giles, J. (2010). Chronic and transient poverty: measurement and estimation, with evidence from China. Journal of Development Economics, 91(2), 266–277.

Du, Y., Park, A., & Wang, S. (2005). Migration and rural poverty in China. Journal of Comparative Economics, 33(4), 688–709.

Flaherty, J. H. (2007). China: the aging giant. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 55(8), 1295–1300.

Flaherty, J. H. (2009). Nursing homes in China? Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 10(7), 453–455.

Giles, J. (2006). Is life more risky in the open? Household risk-co** and the opening of china’s labor markets. Journal of Development Economics, 81(1), 25–60.

Giles, J., & Mu, R. (2007). Elderly parent health and the migration decision of adult children: evidence from rural China. Demography, 44(2), 265–288.

Giles, J., & Yoo, K. (2007). Precautionary behavior, migrant networks and household consumption decisions: an empirical analysis using household panel data from rural China. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 89(3), 534–551.

Green, S. (2010). The rural life and times of China’s aging population, part III: institutional problems. Asia Healthcare Blog (January 27, 2010). (http://www.asiahealthcareblog.com/2010/01/27/the-rural-life-and-times-of-chinas-aging-population-part-iii-institutional-problems/)

Jalan, J., & Ravallion, M. (1999). China’s lagging poor areas. American Economic Review, 89(2), 301–305.

Jalan, J., & Ravallion, M. (2002). Geographic poverty traps? A micro model of consumption growth in Rural China. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 17(4), 329–346.

Jensen, R. T. (2003). Do private transfers ‘displace’ the benefits of public transfers? Evidence from South Africa. Journal of Public Economics, 2003, 89–112.

Jiang, C., & Zhao, X. (2009). A study on the opportunity cost of China’s elderly care. Management World [Guanli Shijie], 10, 80–87.

Kanbur, R., & Zhang, X. (1999). Which regional inequality? The evolution of rural-urban and inland-coastal inequality in China from 1983 to 1995. Journal of Comparative Economics, 27(4), 686–701.

Kanbur, R., & Zhang, X. (2005). Fifty Years of regional inequality in China: a journey through central planning, reform, and openness. Review of Development Economics, 9(1), 87–106.

Knodel, J., & Chayovan, N. (1997). Family support and living arrangements of Thai elderly. Asia-Pacific Population Journal, 12(4), 51–68.

Lee, Y.-J., & **ao, Z. (1998). Children’s support for elderly parents in urban and Rural China: results from a national survey. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 13, 39–62.

Liang, Z., & Ma, Z. (2004). China’s floating population: new evidence from the 2000 census. Population and Development Review, 30(3), 467–488.

Li, S., Song, Lu, & Feldman, M. W. (2009). Intergenerational support and subjective health of older people in rural china: a gender-based longitudinal study. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 28(2), 81–86.

Marriage Law. (2001). The marriage law of the people’s republic of China, Section 3, Article 21. Available online at http://www.nyconsulate.prchina.org/eng/lsqz/laws/t42222.htm.

McGarry, K. (1999). Inter-vivos transfers and intended bequests. Journal of Public Economics, 73(3), 321–325.

Ravallion, M. (1996). Issues in measuring and modeling poverty. The Economic Journal, 106(438), 1328–1343.

Ravallion, M., & Chen, S. (2007). China's (Uneven) progress against poverty. Journal of Development Economics, 82(1), 1–42.

Selden, M. (1993). Family strategies and structures in rural North China. In D. Davis & S. Harrell (Eds.), Chinese families in the post-mao era (pp. 139–164). Berkeley: University of California Press.

State Council. (2009). Guiding suggestions of the state council on develo** a new rural pension scheme pilot. State Council of the People’s Republic of China, Document Number 32 (September 2009).

Wu, B., Mao, Zong-Fu, & Zhong, R. (2009). Long-term care arrangements in Rural China: review of recent developments. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 10(7), 472–477.

Yatchew, A. (1998). Non-parametric regression techniques in economics. Journal of Economic Literature, 36, 669–721.

Yatchew, A. (2003). Semi-parametric regression for the applied econometrician. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Yao, Y. (2006). Issues of old age support for the ‘empty nest’ rural elderly in developed region, a case of Rural Zhejiang Province. Population Research [Renkou Yanjiu], 30(6), 38–46.

Zhao, Y. (2002). Causes and consequences of return migration: recent evidence from China. Journal of Comparative Economics, 30(2), 376–394.

Zimmer, Z., & Kim, S. K. (2002). Living arrangements and socio-demographic conditions of older adults in Cambodia. Population Council Working Paper No. 157. Population Council, New York.

Zimmer, Z., & Kwong, J. (2003). Family size and support of older adults in urban and Rural China: current effects and future implications. Demography, 40, 23–44.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This paper has benefitted from the helpful suggestions of Emmanuel Jimenez, Phillip O’Keefe, Robert Palacios, Maria Porter, Adam Wagstaff and **aoqing Yu and from comments on an early presentation of this work from participants at the Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management (APPAM) meetings held in Los Angeles, November 6–8, 2008. We are also grateful for financial support for supplemental data collection which from the National Science Foundation (SES-0214702), the Michigan State University Intramural Research Grants Program, the Ford Foundation (Bei**g), the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs (Academy Scholars Program) at Harvard University and the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Giles, J., Wang, D. & Zhao, C. Can China’s Rural Elderly Count on Support from Adult Children? Implications of Rural-to-Urban Migration. Population Ageing 3, 183–204 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12062-011-9036-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12062-011-9036-6