Abstract

This study examined the association between literacy and quality of life among rural seniors in the Republic of Korea. A sample of rural seniors (N = 1,000) was surveyed by the Korea Rural Economic Institute in 2018, which assessed their literacy levels, their lifelong literacy education status and their quality of life. The authors’ analyses of the data collected in this survey reveal that higher literacy levels are positively associated with a greater likelihood of social inclusion and better mental health status among rural seniors. Furthermore, seniors with functional literacy demonstrated a higher probability of being included in the rural community compared to those with only basic literacy. Lastly, lifelong literacy education was found to play a crucial role in enhancing the literacy levels of rural seniors. As a policy recommendation, the authors suggest that local governments expand literacy education programmes to more rural areas of South Korea.

Résumé

L’importance de l’alphabétisation pour les seniors dans les zones rurales en Corée du Sud : une enquête concernant ses effets sur l’inclusion sociale et la santé mentale – Cette étude se penche sur le lien entre alphabétisation et qualité de vie pour les seniors dans les zones rurales en Corée du Sud. Une enquête a été menée en 2018 par l’Institut d’économie rurale de Corée sur un échantillon de seniors (N = 1 000) pour évaluer leur degré d’alphabétisation, leur situation en matière d’éducation tout au long de la vie et leur qualité de vie. Les analyses réalisées par les auteurs au sujet des données collectées dans ce cadre révèlent que les seniors des zones rurales avec un degré d’alphabétisation plus élevé ont plus de chances d’être inclus socialement et de jouir d’une meilleure santé mentale. En outre, elles montrent que, par rapport aux seniors avec un niveau de base, il est plus probable que ceux disposant d’un degré d’alphabétisation fonctionnel, soient inclus dans les communautés rurales. Enfin, l’étude indique que l’éducation tout au long de la vie joue un rôle décisif pour améliorer le degré d’alphabétisation des seniors dans les zones rurales. Les auteurs recommandent sur le plan politique que les collectivités locales étendent les programmes d’alphabétisation à davantage de zones rurales en Corée du Sud.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Globally, adult literacy levels have been gradually improving. The UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) estimated a global adult literacy rate of 86% in 2016 (UIS 2017). The fact sheet (ibid.) also shows that almost all regions, including East and South-East Asia, South Asia, North Africa and Western Asia made great progress in improving adult literacy in the period from 1990 to 2016. The Republic of Korea has a high adult literacy rate, estimated at 98.3% in 2008, ranking 17th out of 177 countries (Kim et al. 2014). Considerable progress has been made in the fight against illiteracyFootnote 1 in South Korea, given that the rate was only 50% as recently as the 1950s (Kim 2009).

There are many actual or potentially illiterate seniors in rural South Korea, although the average literacy rate is high (NILE 2018). By potentially illiterate, we mean a person who can read and write basically but has difficulty understanding and writing his or her thoughts. According to the Korean National Institute for Lifelong Education (NILE), the proportion of illiterate people is about 7.2% among those aged 65 and above, considerably higher than the 1.7% illiteracy rate in the overall population. The disparity is even more acute in rural areas. The illiteracy rate for rural seniors stands at 16.2%, compared to 5.7% and 7.2% among seniors in major metropolitan areas and small-to-medium-sized cities, respectively. Potential illiteracy is also common in rural areas. Among female farmers aged 70 or older, 42.9% have never attended school and 92.9% have not progressed beyond elementary school (ibid.).

Adult literacy is closely associated with quality of life in older adults, because literacy is a key skill needed to conduct daily activities. Low rates of literacy make it difficult to implement policies and deliver social services in rural areas. For example, the effective delivery of public education, health, welfare and culture programmes to rural seniors is compromised when many are illiterate and thus cannot understand the purposes and procedures of those programmes. This lack of general understanding means that the benefits of those policies are not evenly distributed among all members of the community.

Although literacy plays an important role in enabling people in rural areas to access various benefits, there is a shortage of adequate research on this topic. Illiteracy is far more prevalent among rural seniors than among other groups, and the illiteracy of rural female seniors is a particular cause for concern. Up until now, few studies have been conducted on the conditions of illiteracy in rural South Korea. Furthermore, there has been no empirical analysis of whether literacy levels significantly affect the quality of life of rural seniors, or of the effectiveness of lifelong literacy education on literacy levels. In South Korea, lifelong literacy education is provided by national institutions and encompasses formal and non-formal literacy teaching and learning for people of all ages.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the benefits of literacy for seniors and to consider the most effective ways of promoting it. We examined the link between literacy and social inclusion and the mental health of rural seniors, as well as the role of literacy education in increasing literacy levels. We conclude our article by identifying the political implications of our empirical analysis.

Literature review

Concepts of literacy

The definition of literacy has long been a topic of debate among researchers and educators. The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines “literate” as “educated, cultured”, or “able to read and write” (Merriam-Webster n.d., online). However, a more nuanced definition of literacy is needed. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO 2005) conceptualises literacy based on a fourfold understanding of literacy. The first element of this concept is “literacy as skills” (ibid., p. 149): a set of tangible skills of reading, writing and numeracy that confer the ability to process, interpret and communicate information. The second element of literacy is “literacy as applied, practised and situated” (ibid., p. 151): the application of skills for socio-economic development varying according to the social or cultural context. The third element of literacy is “literacy as a learning process”. This means that “as individuals learn, they become literate” (ibid., p. 151), regardless of educational interventions for literacy. The fourth element of literacy is “literacy as text” (ibid., p. 152). Based on this fourfold concept, literacy can be acquired by understanding the socio-political and communicative practices within a text. Thus, literacy involves the functional ability to use fundamental skills such as reading, writing and arithmetic in everyday life to manage and solve social tasks and problems (Rassool 1999).

Starting in the 1960s, the concept of literacy was expanded to include “functional literacy”, which refers to the capacity to apply literacy skills effectively in real-life situations (UNESCO 2005, p. 153). Researchers and institutions have defined functional literacy in different ways. William Scott Gray (1969 [1956]) argued that a person is functionally literate when he or she has acquired the knowledge and skills in reading and writing that enable him or her to engage effectively in all activities in which literacy is normally assumed in his or her culture or group. Similarly, UNESCO defined a functionally literate person as

one who can engage in all those activities in which literacy is required for the effective functioning of his or her group and community and also for enabling him or her to continue to use reading, writing and calculation for his or her own and the community’s development (UNESCO 2004, p. 12).

Kenneth Levine (1982) defined functional literacy as the level of practical capability which enables an individual to use knowledge and information obtained from a text in a way suitable for daily life, while Uta Papen (2005) described functional literacy as a skill required for a broad range of activities associated with an individual’s participation in society. Functional literacy is distinguished from basic literacy by emphasising work- and society-related skills rather than individual needs.

In recent decades, the concept of literacy has been expanded further to include critical literacy, which encompasses skills necessary for daily life and citizenship. Critical literacy has been defined by Paulo Freire and Donaldo Macedo as “reading the word” and “reading the world” (Freire and Macedo (2016 [1987]). The goal of critical literacy is to enable learners to comprehend their surroundings and differentiate between justice and injustice, power and oppression. Ira Shor (1999) argued that the distinction between functional and critical literacy lies in the purpose of acquiring literacy. The primary goal of critical literacy is to critique mainstream culture and existing power relationships between social groups, rather than solely to enable a few more literate individuals to attain a higher social status.

Despite the growing focus on critical literacy, it is hard to reliably evaluate its level and impact among adults. Researchers and professionals agree that standardised survey questionnaires are inadequate for this purpose. Some measures of critical literacy have been suggested, such as those by Edward Lehner et al. (2017) and Sultan Sultan et al. (2017), but they have not been officially adopted by national and international organisations which evaluate adult basic and functional literacy.

Literacy, education and social practice

The significance of literacy for social activities cannot be overstated. It plays a crucial role in hel** individuals discover their identity within society and build social capital by participating in various networks. Lyn Tett and Kathy Maclachlan (2007) conducted a two-phase study of 600 literacy and numeracy learners in Scotland and found that literacy led to an increase in social activity, networking and local engagement. Moreover, improvements in literacy skills caused changes in learners’ behaviours and activities which enhanced their self-confidence and identity, resulting in the development of social capital. As such, literacy is not simply a skill, but an activity that individuals undertake with others in society (Barton and Hamilton 2000).

Initially, research on literacy focused on the impact of literacy education on the development of basic literacy and numeracy. However, the current approach emphasises the importance of enhancing literacy skills to improve the quality of individual life and social relationships. Stephen Reder (2008) has underscored the significance of literacy education in hel** adults improve their literacy, citing the economic and social consequences of literacy improvement. Nelly Stromquist (2006) has pointed out that literacy education should be connected to basic education rather than literacy itself, since literacy skills are integrated into an individual’s daily life. Consequently, literacy programmes should be thoughtfully designed, with content selected based on the learner’s own literacy practice.

Moving beyond this, health literacy plays a crucial role in health among older adults. There is general agreement on the significant impact of health literacy on quality of life, including mental and physical health in later life (Chesser et al. 2016; Zheng et al. 2018; Panagioti et al. 2018). Although the relationship between health literacy and older adults’ quality of life has been well documented, the impact of adult literacy on mental health in later life has received relatively little attention. Since literacy is a skill required to conduct daily activities, adult literacy, which encompasses health literacy, is closely associated with quality of life among older adults.

Measuring literacy

There are various ways of classifying literacy levels based on the understandings of literacy discussed above. Initially, literacy was classified in terms of a binary (literacy vs illiteracy). After the concept of functional literacy was widely adopted, researchers classified literacy in terms of three to five levels. Five levels were used in the International Adult Literacy Survey (IALS) conducted by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and in UNESCO’s Literacy Assessment and Monitoring Programme (LAMP) (2005). Table 1 shows how each literacy level was defined by the OECD and UNESCO.

In South Korea, NILE has defined four levels of literacy. The NILE classification includes both basic and functional literacy concepts. Level 1 represents illiteracy; levels 2 to 3 basic literacy, and level 4 functional literacy (NILE 2018). Table 2 shows the definitions and learning levels (school grade equivalents) of each literacy level as formulated by the National Institute for Lifelong Education.

Based on NILE’s definition of literacy, we defined level 1 as “illiteracy” for our study, level 2 as “semi-literacy”, level 3 as “basic literacy” and level 4 as “functional literacy”. Each level was evaluated based on seven question cards, as shown in Figure 1. Each card contained three questions testing basic literacy and four questions testing functional literacy. No correct answer to the basic literacy questions indicated “illiteracy”, while one to two correct answers indicated “semi-literacy”. If a respondent answered the basic literacy questions correctly, but not the functional literacy questions, s/he scored for basic literacy. Respondents who answered all questions correctly scored for functional literacy.

Table 3 shows the definition of literacy applied to this study according to the number of correct answers given.

For this study, we defined “rural seniors” as adults aged 65 or older who resided in towns or townshipsFootnote 2 which were sparsely populated and geographically dispersed. The age limit for rural seniors was applied in accordance with the literacy rate for older persons defined by the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS n.d.).

The concept of “social inclusion” describes full participation in social life, including economic, political and civic activities. The European Union (EU) defines social inclusion as

a process which ensures that those at risk of poverty and social exclusion gain the opportunities and resources necessary to participate fully in economic, social and cultural life and to enjoy a standard of living and well-being that is considered normal in the society in which they live (EU 2010, p. 1).

The United Nations defines it as

the process of improving the terms of participation in society, particularly for people who are disadvantaged, through enhancing opportunities, access to resources, voice and respect for rights (UN 2016, p. 17).

Considering these definitions, we can describe social inclusion as the process of providing socially excluded, disadvantaged, vulnerable individuals and groups with the opportunities and resources to fully participate in society without limitations. The ultimate goal of social inclusion is to enhance people’s abilities to participate in society and play a significant social role.

Measuring social inclusion is challenging due to multidimensional characteristics covering social, economic, political and even spatial domains. Moreover, there is no objective judgement that every researcher agrees with. The United Nations suggests that the indicators of social inclusion/exclusion are access to opportunities for education, employment and participation in society (UN 2016). To evaluate the effects of social inclusion/exclusion in terms of research outcomes, researchers assess the differences in outcomes before and after those who were excluded obtain the relevant opportunities.

Data collection and methodology

Although the National Center for Adult Literacy Education, commissioned by the Korean government, had conducted a national literacy survey in 2017 (NILE 2018), the survey questionnaire for literacy evaluation consisted of 43 questions, which proved to be too lengthy for many elderly respondents to complete. Consequently, the national survey failed to provide an accurate assessment of the literacy levels of elderly citizens in rural areas.

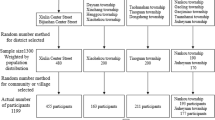

To better evaluate the literacy levels of the rural elderly population in South Korea, the Korea Rural Economic Institute (KREI) therefore modified the survey in 2018 by shortening the length and number of questions with the aim of increasing the response rate among older adults in rural areas. The goal of the survey was to collect primary data on the literacy levels and educational status of citizens aged 65 and over residing in rural areas in order to inform policy development. For the survey, 1,000 older adults aged 65 and above living in rural communities were selected, based on demographic characteristics such as region and gender. Cluster sampling was employed to gather data, with a maximum allowable sampling error of 3.5% points at the 95% confidence level. The survey was conducted in two stages. In the first stage, 30 cities and counties were selected using stratified cluster sampling based on metropolitan areas. In the second stage, square root proportional allocation was employed based on city, gender and age, with age groups divided into three categories: 65–69, 70–75 and 80 or older. The KREI survey was conducted over a period of approximately 5 weeks, from 18 July to 24 August 2018, and collected data on participants’ literacy levels, social and political activities, health status and socio-demographic characteristics.

In the current study, we conducted two empirical analyses of the data collected by KREI. The first evaluated the association between literacy and social inclusion and the mental health status of rural seniors. In this analysis, social inclusion represented (1) the use of public services; (2) community participation; and (3) exclusion from public projects. Another dependent variable represented mental health status, such as feelings of anxiety and depression.

The second analysis investigated the relationship between literacy education and the literacy levels of rural seniors. In this analysis, the dependent variable represented measures of literacy, such as literacy test scores or literacy levels. The key independent variable was the experience of lifelong literacy education provided by the local government for illiterate rural seniors.

The use of public services was measured by the use of post offices and banks. Respondents were asked, “How often do you use post offices and banks?” We coded this variable as 0 if they responded “never”, and as 1 if they responded, “every day”, “every week”, “every month” or “several times a year”. Community participation was evaluated by the question, “How often do you take part in community gatherings?” We coded this variable as 0 if they responded “never”, and as 1 if they responded, “every day”, “every week”, “every month” or “several times a year”. To address exclusion from public projects, we used a variable representing whether or not respondents were excluded from the application of state funds for farmers due to illiteracy. We coded this variable as 0 if they were not excluded, and as 1 if they were excluded.

The mental health status of respondents was also measured by the PHQ-4 scale suggested by Kurt Kroenke et al. (2009). The PHQ-4 scale consists of Generalized Anxiety Disorder 2-item (GAD-2) for feelings of anxiety, suggested by Kroenke et al. (2007), and Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) for feelings of depression, suggested by Kroenke et al. (2003).

Respondents were asked to answer the four questions of the PHQ-4 scale (shown in Table 4), choosing one of four possible responses: “not at all”, “several days”, “more than half the days” or “nearly every day”. To evaluate the degree of depression, we coded this variable as 0 if they answered “not at all” to all questions, and as 1 if otherwise.

Literacy levels were measured by the questions shown in Figure 1. We classified respondents into four literacy levels based on their scores on a literacy test based on the criteria presented in Table 3. Respondents were deemed to have “functional literacy” if they obtained a perfect score in response to both the basic and functional literacy questions. Respondents were deemed to have “basic literacy” if they obtained a perfect score in the basic literacy questions but obtained scores of 0 to 3 in the four functional literacy questions. Respondents were deemed to have “semi-literacy” if they obtained scores of 1 to 2 in the basic literacy questions, regardless of their functional literacy scores. Respondents were deemed to have “illiteracy” if they obtained a zero score in the basic literacy questions.

We took into consideration participation in lifelong education programmes to estimate the correlation between education and literacy level. This variable emerged from a response to the question, “Have you ever had literacy education?”. We coded this variable as 1 if they responded “yes” as well as “taking literacy education now”, and as 0 if they responded “no”. Further, we considered demographic factors, including self-identified gender (male or female), age group (65–69 years, 70–79 years, or 80+ years), and where they lived (town or township).

For our first analysis, we used the full sample, which included 1,000 respondents. For our second analysis, we used a subsample to evaluate the effects of adult literacy education. We estimated the effects of lifelong education programme participation among respondents who had become illiterate since leaving school. The KREI survey asked: “Since when have you been able to read and write?”. Possible answers were “since my school days”, “since over 10 years ago”, “since 10 to 5 years ago”, “since 5 years ago or less”, “currently taking literacy education” or “illiterate”. We removed those respondents who had chosen “since my school days”, which gave us a subsample of 193.

For the first analysis, we used logistic regression with robust standard errors, and reported the odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. For the second analysis, we used binomial regression with a logit link function and then ordered logistic regression, reporting the marginal effects and standard errors. Since the estimates of coefficients do not indicate the marginal effects of the relevant covariates for the second analysis, we evaluated the marginal effects and interpreted them. Each marginal effect we estimated showed the probability of changing from the current to a higher level, as the 1-unit of a covariate increases.

Results

Our results show that a significant proportion of rural elderly individuals in South Korea possess inadequate levels of literacy (Table 5). Specifically, 4.9% of the respondents were found to be illiterate, 16.6% exhibited semi-literacy, 36.1% demonstrated basic literacy, and 35.7% were assessed to be functionally literate. Of the respondents in rural areas, 21.5% required basic literacy education at elementary school level, while 57.6% required intermediate literacy education at the middle school level. Because the literacy level of women aged 75 or older and residing in townships was considerably lower than that of males under the age 75 living in towns, a higher percentage of female seniors (27.8%) was deemed in need of basic literacy education compared to males (13.5%). Furthermore, a far greater percentage of elderly individuals over the age of 75 (33.5%) required basic literacy education compared to those under the age of 75 (8.7%).

Table 6 shows the results of our first empirical analysis, reporting the estimated association between literacy levels and social inclusion and mental health status of rural seniors. The estimation results included the odds ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals for the logistic regressions. The following discussion refers to the odds ratios and considers their effects statistically significant if the reported confidence interval includes 1, unless otherwise noted.

We found a significant relationship between literacy levels and the use of public services. Rural seniors wo were more literate were more likely to use banks and post offices than those who had low or no literacy. The likelihood of visiting banks and post offices was predicted to be about 3.17 times greater among those who had basic literacy than among illiterate rural seniors. If rural seniors became functionally literate, the likelihood increased by 5.25, holding all other variables constant.

Rural seniors with high literacy levels were more likely to attend community organisations or gatherings and to socialise with neighbours. The likelihood of participating in rural communities was predicted to be about 2.05 times greater among those who were functionally literate than among illiterate seniors.

If rural seniors were literate enough to understand information about government support, they were less likely to be excluded from public subsidy projects for farmers. The likelihood of being excluded from these projects was predicted to be 0.46 times lower among those who had basic literacy than among rural seniors who were illiterate. For seniors who were functionally literate, the likelihood decreased by 0.32, holding all other variables constant.

The KREI survey also included questions evaluating mental health status based on the PHQ-4 scale. Functional literacy was positively associated with higher mental health status among rural seniors. If seniors were functionally literate, they were less likely to suffer from the mental health conditions of anxiety and depression. The likelihood of experiencing a mental health condition was predicted to be 0.48 times lower among those who were functionally literate than among illiterate seniors.

Table 7 shows the results of our second empirical analysis, reporting the estimated relationship between lifelong literacy education and literacy levels. The estimated results included the marginal effects and corresponding standard errors for the binomial regression with the logit link and the ordered probit regression. The following discussion refers to the marginal effects and considers the effects statistically significant if the p-value was less than 0.05, unless otherwise noted.

As we expected, lifelong literacy education for rural seniors was significantly and positively associated with literacy levels. Participation in lifelong literacy education increased the probability of obtaining higher scores from the literacy questions. On average, there was an 89.7% greater chance that a respondent who had participated in lifelong literacy education attained higher scores on the basic literacy questions than one who had not. Lifelong literacy education was the only statistically significant variable among the other covariates we considered. The probability of answering the functional literacy questions correctly also increased by 32.8% if a respondent had participated in lifelong literacy education.

The probability of illiteracy decreased by 19.5% if a respondent had participated in lifelong literacy education. As respondents’ literacy levels improved, the chances of having basic and functional literacy increased by 14.8% and 7.5%, respectively, if they participated in lifelong literacy education. If rural seniors who were illiterate took part in lifelong literacy education, the chances were greater that s/he became literate, even functionally literate.

Discussion

To validate our results, we compared them with those of the national survey conducted in 2017 by the National Center for Adult Literacy Education, a government-funded research institute (NILE 2018). Our findings indicated a high degree of consistency and a lack of significant differences between the two surveys. In the national survey, levels 1 and 2 were classified as illiteracy and semi-literacy, while levels 3 and 4 were classified as basic and functional literacy, respectively. The proportion of illiteracy and semi-literacy we found in our own survey was 21.5%, while the proportion of levels 1 and 2 in the national survey was 16.2% in rural areas. The proportion of basic and functional literacy in our survey was 78.5%, and that of levels 3 and 4 in the national survey was 76% in rural areas. Notwithstanding the brevity and simplicity of the questions in our survey, they proved to be reliable indicators of the full spectrum of literacy domains.

Literacy among elderly individuals in rural areas is associated with opportunities to participate in various social groups and activities. The literature suggests that improved literacy increases the likelihood of interacting with other members of society, building social networks, and experiencing a sense of belonging. Thus, the relationship between literacy and social activities is particularly significant in rural areas. Illiterate rural seniors are more hesitant about using public services and participating in the community. They also experience exclusion from public subsidies and government projects for farmers. After becoming literate, they make efforts to be included in decision-making processes in their rural communities. In rural South Korea, there is a tradition of community cooperation due to the fact that farming requires collective labour. When illiterate seniors are excluded from participation in the rural community, they experience isolation and their quality of life deteriorates. Thus, literacy is a significant means of increasing the quality of life of rural seniors.

For rural seniors, literacy has been shown to be a significant factor in reducing feelings of depression and anxiety. Although a causal relationship between literacy and mental health status is not clearly demonstrated by our estimation results, our findings do indicate two factors that contribute significantly to mental health: (1) an increase in social involvement; and (2) improved health literacy.

First, when illiterate rural seniors become literate, they are more likely to visit public places and attend social gatherings. As they get more and more involved in society, the loneliness and depression they experienced reduces or disappears. Conversely, when older adults experience a reduction in their networks and social contacts, they are more likely to become isolated and suffer from mental health problems (Forsman et al. 2013; Forte 2009). Literacy can play a significant role in increasing their participation in the community and in reducing the isolation that causes depression or anxiety.

Second, health literacy can play a significant role in improving mental health (Serper et al. 2014; Wolf et al. 2005). The test of functional literacy in our study included a question designed to evaluate whether or not respondents could read and understand medication instructions. Thus, functional literacy can act as a partial proxy for health literacy.

Furthermore, functional literacy is more significant than basic literacy in increasing social inclusion and improving the mental health of rural older adults, since functional literacy enables individuals to communicate effectively with others in their communities, which is essential in daily life. According to the literature, basic literacy involves the ability to read texts and perform simple calculations, whereas functional literacy encompasses the ability to interact and engage with others, which might serve as a foundation for achieving critical literacy. Without functional literacy, a person may struggle to solve complex problems and fully understand the context of various types of information. Basic literacy is merely the starting point for rural seniors to achieve a better quality of life. Achieving functional literacy, or even critical literacy, is essential for realising the goal of literacy in daily life.

In rural areas, learners face personal, institutional and environmental restrictions which limit their participation in education. The national survey mentioned earlier shows that the average rate of functional literacy was about 77.6% in 2017 (NILE 2018). However, in our survey we found the functional literacy rate among rural seniors to be only about 42.4%, which is 35.2 percentage points lower than the national level. This indicates that many seniors in rural areas can read and write, but they would still face difficulties caused by functional illiteracy in their daily lives. The reason for this seems to be the lack of access to qualified education resources due to geographical inconveniences and a shortage of trained educators. According to Sam-Geun Kwak and Suk-Won Lee (2003) and Sang** Ma (2014), negative factors that hinder rural elderly participation in literacy education include personal factors, such as psychological and physical problems, and social factors, such as limited access to education information and a lack of educational infrastructure and educators in rural areas. Additionally, although the quantity of literacy education services has increased considerably in rural South Korea over the past decades, challenges of quality remain. The national-level literacy education programme has been running for 10 years and has educated 70,000 rural seniors so far. However, since literacy education is designed as a short-term programme, it focuses on very basic reading skills. Moreover, most literacy educators are volunteers, making it difficult to ensure professional expertise (Shin 2006; Choi and Lim 2015).

Lifelong education for literacy is one of the most effective policies for increasing literacy in rural areas. In the framework for our study, lifelong literacy education is the only policy that increases literacy levels. We found that illiteracy among rural seniors stemmed from a lack of educational opportunities, which tended to be significantly worse in women, reflected in the fact that women account for 81.6% of illiterate rural seniors. Young-sook Heo and Young-hwa Kee (2008) point out that elderly women were traditionally deprived of educational opportunities due to patriarchal social norms and historical conditions. Elderly women suffered from severe poverty in their childhood and adolescence during Japanese colonial rule and the Korean War. They were not offered the chance to study due to the gender discrimination prevalent in South Korea in the first half of the 20th century. Thus, if appropriate educational opportunities are given to illiterate seniors, they can finally improve their literacy levels as well as their quality of life.

The results of our study emphasise the link between demand for literacy education and lifelong learning. They show a significant positive impact of full functional literacy on quality of life for rural seniors. However, the current literacy education programme for rural areas only provides education for basic literacy, not for functional literacy.

A similar trend is observed internationally. The 5th Global Report on Adult Learning and Education (GRALE 5) showed significant increases (49%) in participation in literacy and basic skills programmes, as well as continuing training and professional development programmes, since 2018 (UIL 2022, p. 83). The same period also saw an increase of 40% in participation in citizenship skills education (ibid.), including liberal, popular and community education. While active citizenship training in continuing education has been steadily increasing, it has been slow to develop compared to basic or occupational competencies. In the previous report (GRALE 4), 27% of respondents (representing responsible government ministries) answered “don’t know” in relation to in the active citizenship competency (UIL 2019, p. 38), which may indicate disinterest in citizenship education.

Conclusion and policy implications

This study has shown that literacy is vitally important for rural seniors. Illiterate seniors in rural areas were more likely to be excluded from their communities and to suffer mental health problems. Many rural seniors were excluded in the past from the right to be educated and to pursue happiness, yet our society still does not pay sufficient attention to them. The central and local governments should implement policies to increase their literacy and embrace rural seniors as full community members.

Although lifelong literacy education has turned out to be effective in increasing literacy levels, only a small number of rural seniors currently benefit from literacy education. If illiterate seniors enrol in the lifelong literacy education programmes provided by local governments, they can learn to read bus timetables, novels and poems, and write letters, all of which they were unable to do previously. However, local governments cannot meet these educational needs due to budget shortages. Thus, budgets for lifelong literacy education need to be expanded.

Literacy education should go beyond the framework of simple education in which only the abilities to read and write are developed. Social inclusion will not be guaranteed unless the literacy levels of rural seniors reach functional literacy. The next step for literacy education is to let rural seniors achieve functional literacy over basic literacy. For this purpose, literacy education should be linked with other lifelong education programmes to enhance functional literacy and the sustainability of education. The government needs to realise the importance of literacy education and pay more attention to the literacy learning process by investing more in the overall lifelong learning system.

Literacy education should be linked to post-secondary lifelong learning to support functional literacy in a variety of fields. Current literacy education focuses on basic literacy – reading, writing, and interpreting characters – but goes no further. We observed that respondents who had participated in lifelong literacy education experienced improvements in their abilities to answer correctly the first three questions in Figure 1. However, the effect falls to half when respondents answered the last four answers correctly. Lifelong literacy education should be used to promote functional literacy beyond basic literacy through literacy education programmes tailored to the needs and abilities of seniors and to provide more basic education opportunities for illiterate rural seniors.

The South Korean government has focused its policies and budgets on building a lifelong education system for members of the public with high school completion certificates or above, based on the (mis)perception that illiteracy has all but disappeared in South Korea. However, they have failed to notice the illiteracy of marginalised seniors, in particular elderly women in rural areas. Thus, the government needs to pay special attention to older rural adults. First, a national survey system should further investigate literacy among seniors and the association between illiteracy and people’s daily activities in rural areas. Also, special education and literacy education programmes for rural seniors should be provided.

Local governments need to fund and support on-site literacy education programmes in rural areas. In South Korea, there are many locations, such as elementary schools and community centres, which are no longer used due to the declining rural population. However, there are administrative limitations on using such places for literacy education. If the administration and education departments of local governments could cooperate to support on-site education, literacy learning spaces for rural marginalised seniors could be provided at low cost.

Local governments should guarantee sustainable lifelong literacy education regardless of the political or administrative environment. Current lifelong literacy education programmes in South Korea depend on the enthusiasm of local government officials and the interest of mayors, but not on a lifelong educational system or municipal ordinance. If the officials change or a mayor loses an election, educational opportunities could disappear. Establishing a literacy education system should be the first priority for continuing to maintain lifelong education for rural seniors regardless of the political environment.

Furthermore, the infrastructure for literacy education in rural areas is less developed than in urban areas. Learners are dispersed across a vast area, making it challenging to implement literacy education with the same system used in urban areas. Moreover, the slow learning speed of elderly learners in rural areas should be considered when designing literacy education programmes. It is essential to design literacy education programmes tailored to the needs and challenges of rural elderly learners and provide them with adequate support.

Further studies should investigate the effectiveness of lifelong literacy education in improving social inclusion and mental health. As the rural population has declined and the percentage of people over age 65 has soared (Shim et al. 2018), many elderly farmers find themselves living in remote places with limited opportunity to socialise. Illiterate seniors suffer from loneliness more than ever before. Lifelong literacy education improves social inclusion and mental health by strengthening social networks in rural communities and increasing literacy levels.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Notes

While being aware that the literate–illiterate dichotomy is rejected by some scholars in favour of a continuum from low to high literacy (see for example Hanemann and Robinson 2022), our use of the term “illiteracy” throughout this article refers to no and very low literacy.

In rural South Korea, each county (gun 군/郡) has regional administrative towns (eup 읍/邑) and a number of townships (myeon 면/面), which are subdivided into villages (ri 리/里).

References

Barton, D., & Hamilton, M. (2000). Literacy practices. In D. Barton, M. Hamilton, & R. Ivanič (Eds.), Situated literacies: Theorising reading and writing in context (pp. 7–15). London: Routledge.

Chesser, A. K., Keene Woods, N., Smothers, K., & Rogers, N. (2016). Health literacy and older adults: A systematic review. Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine, 2, Article no. 11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333721416630492

Choi, Y., & Lim, C. (2015). 비문해 농촌 여성노인의 문해교육 경험과 삶의 변화[The literacy education experience and changes in life of the illiterate rural female seniors]. 한국가족관계학회지 제 [Korean Journal of Family Relations], 20(1), 165–193.

EU (European Union) (2010). The European social fund and social inclusion: Summary fiche. Brussels: European Commission. Retrieved 12 January 2024 from https://ec.europa.eu/employment_social/esf/docs/sf_social_inclusion_en.pdf

Forsman, A., Herberts, C., Nyqvist, F., Wahlbeck, K., & Schierenbeck, I. (2013). Understanding the role of social capital for mental wellbeing among older adults. Ageing and Society, 33(5), 804–825. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X12000256

Forte, D. (2009). Relationships. In M. Cattan (Ed.), Mental health and well-being in later life (pp. 84–111). Maidenhead: Open University Press/McGraw-Hill.

Freire, P., & Macedo, D. (2016 [1987]). Literacy: Reading the word and the world. London: Routledge.

Gray, W. S. (1969 [1956]). The teaching of reading and writing: An international survey. Monographs on Fundamental Education, No. 10. Enlarged edn. Paris: UNESCO. Retrieved 12 January 2024 from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000002929

Hanemann, U., & Robinson, C. (2022). Rethinking literacy from a lifelong learning perspective in the context of the Sustainable Development Goals and the International Conference on Adult Education. International Review of Education, 68(2), 233–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-022-09949-7

Heo, Y., & Kee, Y. (2008). 노인여성학습자의 문해교육 참여에 관한 연구 [A study of participation of the aged women on literacy education]. 평 생 교 육 ․ HRD 연 구 [Korean Journal of Lifelong Education and HRD], 4(1), 29–57. https://doi.org/10.35637/klehrd.2008.4.1.002

Kim, S. I. (2009). 2008 국민의 기초 문해력 조사 개요 [Overview of the 2008 National Basic Literacy Survey]. 새국어생활 [New Korean Language Life], 19(2), 17–32.

Kim, J., Cho, W., Moon, M., Park, H., Cho, J. M., Park, J. H., & Song, J. (2014). Education for All 2015 national review report: Republic of Korea. **cheon-gun: Korean Educational Development Institute et al. Retrieved 12 January 2024 from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000229721

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2003). The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: Validity of a two-item depression screener. Medical Care, 41(11), 1284–1292. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000093487.78664.3c

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B., Monahan, P. O., & Löwe, B. (2007). Anxiety disorders in primary care: Prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Annals of Internal Medicine, 146(5), 317–325. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B., & Löwe, B. (2009). An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: The PHQ–4. Psychosomatics, 50(6), 613–621. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613

Kwak, S., & Lee, S. (2003). 평생교육 참여결정이론에 관한 연구 [A study of participation theory in lifelong education]. 교육과학연구 [Journal of Education Studies], 34(3), 87–133.

Lehner, E., Thomas, K., Shaddai, J., & Hernen, T. (2017). Measuring the effectiveness of critical literacy as an instructional method. Journal of College Literacy and Learning, 43(1), 36–53. Retrieved 12 January 2024 from https://academicworks.cuny.edu/bx_pubs/22

Levine, K. (1982). Functional literacy: Fond illusions and false economies. Harvard Educational Review, 52(3), 249–266. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.52.3.77p7168115610811

Ma, S. (2014). 농업인의 교육참여 실태와 관련변인-2006년 정부의 농업 교육 투자 확대 이후 변화 탐색 [Farmers’ education participation and its related variables: Exploring the changes since 2006 Agricultural Education Reform]. 농업교육과 인적자원개발 [Journal of Agricultural Education and Human Resource Development], 46(2), 83–106.

Merriam-Webster (n.d.). Literate. In Merriam-Webster dictionary [online resource]. Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 6 February 2024 from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/literate

NILE (National Institute for Lifelong Education) (2018). 2017성인문해능력조사[2017 Adult Literacy Survey]. Seoul: National Center for Adult Literacy Education. Retrieved 12 January 2024 from https://www.nile.or.kr/usr/wap/detail.do?app=11526&seq=724&lang=ko#

Panagioti, M., Skevington, S. M., Hann, M., Howells, K., Blakemore, A., Reeves, D., & Bower, P. (2018). Effect of health literacy on the quality of life of older patients with long-term conditions: a large cohort study in UK general practice. Quality of Life Research, 27(5), 1257–1268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1775-2

Papen, U. (2005). Adult literacy as social practice: More than skills. London/New York: Routledge.

Rassool, N. (1999). Literacy for sustainable development in the age of information. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781800418035

Reder, S. (2008). Scaling up and moving in: Connecting social practices views to policies and programs in adult education. Literacy and Numeracy Studies, 16(2), 35–50.

Serper, M., Patzer, R. E., Curtis, L. M., Smith, S. G., O’Conor, R., Baker, D. W., & Wolf, M. S. (2014). Health literacy, cognitive ability, and functional health status among older adults. Health Services Research, 49(4), 1249–1267. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12154

Shim, J., Sung, J., & Seo, H. (2018). 제5장 사람이 돌아오는 농촌만들기 [Chapter 5 Creating a rural community where people return]. Naju-si: Korea Rural Economic Institute. Retrieved 12 January 2024 from https://aglook.krei.re.kr/main/uEventData/1/download/683/5756/pdf

Shin, M. (2006). 한국 여성노인의 문해교육 현황과 정책 [Literacy education for the female elderly in Korea]. 한국동북아논총 Journal of Northeast Asian Studies, 12(45), 261–284.

Shor, I. (1999). What is critical literacy? Journal of Pedagogy, Pluralism, and Practice, 1(4), Article no. 2. Retrieved 12 January 2024 from https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/jppp/vol1/iss4/2

Stromquist, N. (2006). The political benefits of adult literacy. Background paper prepared for the EFA Global Monitoring Report, 2006. Paris: UNESCO. Retrieved 12 January 2024 from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000146187

Sultan, S., Rofiuddin, A., Nurhadi, N., & Priyatni, E. T. (2017). The effect of the critical literacy approach on pre-service language teachers’ critical reading skills. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 71, 159–174. https://doi.org/10.14689/ejer.2017.71.9

Tett, L., & Maclachlan, K. (2007). Adult literacy and numeracy, social capital, learner identities and self-confidence. Studies in the Education of Adults, 39(2), 150–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/02660830.2007.11661546

UIL (UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning) (2019). 4th Global Report on Adult Learning and Education. Leave no one behind: Participation, equity and inclusion. Hamburg: UIL. Retrieved 12 January 2024 from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000372274

UIL (2022). 5th Global Report on Adult Learning and Education. Citizenship education: Empowering adults for change. Hamburg: UIL. Retrieved 16 February 2024 from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000381666

UIS (UNESCO Institute for Statistics) (n.d.) Elderly literacy rate [online glossary]. Montreal: UIS. Retrieved 16 February 2024 from https://uis.unesco.org/en/glossary-term/elderly-literacy-rate

UIS (2017). Literacy rates continue to rise from one generation to the next. Fact Sheet No. 45 FS/2017/LIT/45. Montreal: UIS. Retrieved 12 January 2024 from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000258942

UN (United Nations) (2016). Leaving no one behind: The Imperative of inclusive development. Report on the world social situation 2016. ST/ESA/362. New York: United Nations. Retrieved 12 January 2024 from https://www.refworld.org/docid/5840368e4.html

UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) (2004). The plurality of literacy and its implications for policies and programmes. Paris: UNESCO. Retrieved 12 January 2024 from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000136246

UNESCO (2005). EFA global monitoring report 2006: Literacy for life. Paris: UNESCO. Retrieved 12 January 2024 from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000141639

Wolf, M. S., Gazmararian, J. A., & Baker, D. W. (2005). Health literacy and functional health status among older adults. Archives of Internal Medicine, 165(17), 1946–1952. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.165.17.1946

Zheng, M., **, H., Shi, N., Duan, C., Wang, D., Yu, X., & Li, X. (2018). The relationship between health literacy and quality of life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 16(1), 201–201. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-018-1031-7

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, S., Kim, N. & An, S. The importance of literacy for rural seniors in the Republic of Korea: An investigation of its effect on social inclusion and mental health. Int Rev Educ 70, 143–162 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-023-10042-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-023-10042-w