Abstract

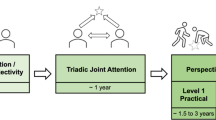

The aim of this paper is to motivate the need for and then present the outline of an alternative explanation of what Dan Zahavi has dubbed “open intersubjectivity,” which captures the basic interpersonal character of perceptual experience as such. This is a notion whose roots lay in Husserl’s phenomenology. Accordingly, the paper begins by situating the notion of open intersubjectivity – as well as the broader idea of constituting intersubjectivity to which it belongs – within Husserl’s phenomenology as an approach distinct from his more well-known account of empathy (Einfühlung) in the Fifth Cartesian Meditation. I then recapitulate and criticize Zahavi’s phenomenological explanation of open intersubjectivity, arguing that his account hinges on a flawed phenomenology of perceptual experience. In the wake of that criticism, I supply an alternative phenomenological framework for explaining open intersubjectivity, appealing to the methodological principles of Husserl’s genetic phenomenology and his theory of developmentally primitive affect. Those principles are put to work using the resources of recent studies of cognitive developmental and social cognition. From that literature, I discuss how infants learn about the world from others in secondary intersubjectivity through natural pedagogy. Lastly, the paper closes by showing how the discussion of infant development explains the phenomenon of open intersubjectivity and by highlighting the relatively moderate nature of this account compared to Zahavi’s.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

It is worth noting that constituting intersubjectivity itself refers to various phenomena, not all of which occur below the level of empathy as it is conceived in the discussion of empathy of the Fifth Cartesian Meditation. We will only concern ourselves here with the low-level variety of constituting intersubjectivity lying beneath empathy.

This is very close to the distinction Gallagher (2009) draws between the problem of social cognition and that of participatory sense-making. The former roughly corresponds to what we will call constituted intersubjectivity, and the later closely resembles the notion of constituting intersubjectivity. In that vein, Gallagher writes, “The question that PSM [participatory sense-making] addresses is: How do we, together, in a social process, constitute the meaning of the world? In contrast, the problem of social cognition is centered on the following question: How do we understand another person?” (Gallagher 2009, 297)

It has to be admitted that, in trying to work out a consistent and detailed account of constituting intersubjectivity in this way, we are going beyond Husserl’s own position, which was quite ambiguous, as Lee (2002, 172–178, 181; see also Zahavi 2001, 56–58) shows. Husserl never conclusively endorsed and defended the view that constituting intersubjectivity has priority – statically, of course, but also genetically – over constituted intersubjectivity. A forthright construal of what I am up to, then, is to say that I am mining Husserl’s works to show what a Husserlian account would look like if it took one direction rather than another on this point, namely, the direction favoring the genetic primacy of constituting intersubjectivity.

The relative narrowness of my target must be kept in mind. This discussion only directly bears on Zahavi’s reading of Husserl. Hence, it may not have the same critical relevance to Zahavi’s separate, more Heideggerian and Sartrean styled description of a very similar phenomenon highlighting the public character of the world. See Zahavi 2005, 163–168, 174–177. This discussion, further, does not directly address another similar phenomenon from Husserl’s (in this instance, Kant-indebted) phenomenology, namely, the normatively “objective” character of our experience of the world, which refers one to other subjects who likewise experience the world. This is, as Russell says, a “strong notion of objectivity […] [that] implies existence in itself and therefore that the [experienced] object is the same for all rational subjects” (Russell 2006, 163).

I will occasionally prefer language connoting the visual sensory modality in particular, because I find that instance more than others facilitates understanding of the phenomena under consideration. But the claims about perceptual presence and open intersubjectivity hold good, presumably, for any sensory modality.

This is not exactly how Zahavi (2001, 45–46) presents his argument, although it is in essence the same. He lumps memory and expectation together, where it seems better to me to separate them. Memory (i.e., Wiedererinnerung) is the ability to return to discrete episodes of past experience (ideally) in all their richness, whereas expectation is, even when informed by past experience, inherently vague, and, when made intuitively present in an overt intentional act, only targets certain general features of the expected experience with any determinacy, leaving the details to be arbitrarily filled in. In the latter respect, then, overtly presentifying expectation is shown also to have a very close resemblance to imagination. There are deep affinities between all three phenomena. So it seems to me the two – memory and expectation – are sufficiently different to separate from one another. This is, however, is minor, terminological point and not a criticism of Zahavi’s argument.

I use the terms “sensitive” and “responsive” (and their cognates) as equivalents. The idea is that even in the simplest sensory experience, one is not the passive recipient of stimuli disconnected from some possible subsequent response. Our sensitivity or responsivity – the way we pick up information in our environment – is an active process, something we simultaneously do and undergo. See Barrett (2011, 96–97) and Noë (2004).

I should note that James Gibson’s ecological psychology is a minority view in the philosophy of perception. Gibson’s (1979) view was criticized by Jerry Fodor and Zenon Pylyshyn (1981), and that critique successfully persuaded most philosophers of mind and cognitive science. Advocates of ecological psychology do, of course, have a response (e.g., Turvey, Shaw, Reed, and Mace (1981)) to Fodor and Pylyshyn (1981). For a summary of the research spawned since that debate and a theoretical clarification, see Chemero (2009). For a prospectus of ongoing and future research from the ecological psychology perspective, see Wilson and Golonka (2013). For an alternative theoretical rendering of ecological psychology (i.e., viz. Chemero 2009), see Rowlands (2010).

See the discussion of this research in Sheets-Johnstone (2000), 346.

Certainly, this argument does not show that CPA is incoherent, contradictory, or psychologically/phenomenologically impossible. All it does is weaken the claim that perception necessarily tracks co-present aspects. Perception can get along, i.e., in it the perceiver can pick out solid, medium sized masses, without the added labor of worrying about what is out of sight. So it’s still entirely possible that some instances of perception involve tracking co-present aspects. But it’s not necessarily so. Fortunately, that is all the present argument requires.

I am modeling my notion of “arousal” after Husserl’s notion of affective allure (Reiz). See, e.g., Husserl 1973d and Husserl 2001. They differ in an important respect, however, because in Husserl’s view, arousal functions in perception alongside other intentional components tracking co-present aspects. The latter is exactly what I want to deny. I think arousal replaces rather than complements the intentional components (referred to as “perceptual sense” in Husserl 1983) that track co-present aspects.

This implies that any pertinent founding relations are included in the static analysis. On Husserl’s view, to grasp the phenomenon with evidence means gras** its essence, and this essence will include such relations. For instance, a perceiver does not have an evident perceptual grasp of a pen as a functional item unless the perceiver also grasps it as a simple material object. To evidently see the pen in its essence thus involves a grasp of the object under all the descriptions required for its presence, e.g., including the object under its description as a simple material object. It is of no use, that is, if it cannot enter into causal relations with my material body and other material objects. Hence, its use value is “founded” in its character as a material object (cf. Husserl 1989).

I mean “constitutive” here in the ontological sense, where a constitutive feature is a necessary part or moment of some whole, rather than in the phenomenological sense, where “constitutive” refers to the properties of a conscious experience by virtue of which that conscious experience “gives,” presents, or manifests something for the conscious subject.

I am borrowing this terminology from De Jaegher, Di Paulo and Gallagher (2010).

I will leave out of consideration the problem of the place of genetic phenomenology in the Fifth Cartesian Meditation. That text is a curious amalgam of static and genetic methods. See Lee (2002) for a discussion.

There I explain the relation of instinct and affection in Husserl’s later work, arguing that the account of instinct is a refined and more complex account of affect that includes the kind of phenomena Husserl’s earlier account of affect sought to describe. For reasons given in that article, I will take it for granted that “affect” and “instinct” refer to the same kind of mental phenomena, although not too much hinges on this terminology here. It works just as well if we assume, the other way around, that instinct is a member in the broader class of affective phenomena.

This way of putting it may seem to run counter to how Husserl sometimes speaks of affection as the pull of the object. That way of speaking is, however, entirely metaphorical, and should not be taken literally (as, e.g., Steinbock 2004 does). Affect does correlate, sometimes in very precise ways (e.g., as in the case of association (Husserl 2001)), with certain contents, but the contents do not instigate the affect. It is just the other way around. Affect is the condition and motivation for anything to be constituted. See Husserl 2001, §§32-35, Mensch 2010, 219–219, and Biceaga 2010, 38–41. Divorcing the function of specifying objects’ properties from affect does not make it “subjective,” it should be noted. Affect is still essentially tied to intentionality, inasmuch as its motivation ineluctably compels and modulates the subject’s intentional directedness to her surroundings. The details provided in what follows should support that claim.

Husserl makes it exceedingly clear (Husserl 1973b, 335) that this is his position by contrasting it with the “vulgar nativism” of Scheler’s postulation of “innate representations [Vorstellungen,]” which he rejects as “the contrary of a genuine phenomenological theory.” At issue is how to account for the intentional constitution of this basement level of conscious life in its earliest moments. As Husserl sees it, his own view of the instincts tries to account for this constitution, whereas Scheler takes the existence of innate representations as a given and only subsequently introduces intentionality into the picture.

One might worry here that this would be too alien of an addition to the Husserlian framework. The latter is supposed to operate under the aegis of the phenomenological reduction (Husserl 1983), that is, from the transcendental standpoint. But now we are turning to empirical research, which no one pretends to take up from a transcendental standpoint. This is an important methodological problem. I do not mean to suggest that the studies referred to are themselves phenomenological in nature. I am optimistic, however, that they are amenable to phenomenological interpretation (or, perhaps, re-interpretation). This should not be problematic, and it is the path one must take given the inability of infants and very young children to do phenomenology themselves. If someone is to grasp the genetic phenomena that unfold in the life of such subjects, one will have to proceed by making careful “empirical” observations, as part of a “phenomenological psychology.” Husserl endorses such a practice, which he calls an approach “from without,” in certain later manuscripts (e.g., Husserl 2006, text 46 and Husserl 2008, text 43, Lee 1993, 156). One can also find Husserl himself implementing this practice (e.g., Husserl 1973c).

For a more graduated, fine-grained account emphasizing the graduality and continuity of the transition, see Reddy (2008), 113–119.

Hence, the Husserlian account of “pairing” from the Fifth Cartesian Meditation (Husserl 1999, §51) is bypassed. That’s not to say pairing never happens or does not figure somewhere in cognitive ontogeny, but only that it is not here that Husserl’s analyses would find their factual counterpart. This passing polemical point, though, does not concern SOI.

This point may be somewhat misleading. To deny mindreading here need not – and this should hopefully be apparent from what follows – rule out that nevertheless some form of social understanding may take place.

I think one could sensibly maintain that this is not really the same idea Zahavi (2001) finds in Husserl. There is room for disagreement. Given the problems afflicting that position, as discussed above, and the phenomenological kinship of the two approaches, in that they are both interested in a pervasive, low-level perceptual experience of a shared, public world, I believe what I am presenting is well construed as a replacement of Zahavi’s (2001) presentation of open intersubjectivity.

Driving this point home a little further, it is not at all clear how other subject’s constitute anything on SOI. As Zahavi himself admits, constitution typically refers to an actually occurring event, whereas the other subjects called upon in his account are merely possible subjects (Zahavi 2001, 50–52). A merely possible subject does not constitute anything, in the strict sense. So others are only “constitutively” involved in open intersubjectivity in a highly equivocal sense. Further, it is unclear how the implicit reference to other subjects might be fulfilled, or that the perceiving subject according to SOI would be capable of engaging another subject in joint constitution by following that reference without any additional resources. So, this view not only fails to show how subjects actually constitute experience together, it also fails to show how such a joint achievement could come about. MOI avoids both of these problems. It explains how one can participate with other subjects in constituting endeavors that institute novel and lasting possibilities for interacting in the world. Hence, this process not only brings new information to light for the infant, but, as a possibility originally presented in the form of a collaborative and altercentrically guided interaction with the environment, it also leaves the door open for further interactions with other subjects.

This would be the consequence of views like Gallagher’s (2005), where he speaks of a translation of other’s embodied emotions in infant imitation. This translation suggests that the difference rather than the similarity between the imitator and its target is central to the transaction. Alter-centric views like those of Stern (1985) and Bråten (2008) and second-person views like those of Reddy (2008) and Fuchs (2012) also argue for the non-derived (e.g., on the basis of a primary ego-centric perspective) character of the infant’s understanding of other subjects.

This should not be taken as “rock bottom” for conscious life. The sensitivity within secondary subjectivity is a transformation of sensitivities that were present already in primary intersubjectivity, as indicated above. Yet, at some point we must reach rock bottom, and it seems to me that what will be found there is the same sort of primitive affect as described in Section 4. Even here, though, we have really only reached relatively rock bottom, because the question of phylogenetic development remains open. These considerations point to a rich field of research for developmental studies and phenomenology.

References

Barrett, L. (2011). Beyond the brain: How body and environment shape animal and human minds. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Biceaga, V. (2010). The concept of passivity in Husserl’s phenomenology. Dordrecht: Springer.

Bråten, S. (2007). Altercentric infants and adults: On the origins and manifestations of participant perception of others’ acts and utterances. In S. Bråten (Ed.), On being moved: From mirror neurons to empathy (pp. 111–136). Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Bråten, S. (2008). Intersubjective enactment by virtue of altercentric participation supported by a mirror neuron system in infant and adult. In F. Morganti, A. Carassa, & G. Riva (Eds.), Enacting intersubjectivity: A cognitive and social perspective on the study of interactions (pp. 133–148). Amsterdam: IOS Press.

Butterworth, G. (2004). Joint Visual Attention in Infancy. In G. Bremner & A. Slater (Eds.), Theories of Infant Development (pp. 317-354) Malden. MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Chemero, A. (2009). Radical embodied cognitive science. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Costall, A. (1995). Socializing affordances. Theory & Psychology, 5(4), 467–481.

Costello, P. (2012). Layers in Husserl’s phenomenology. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Csibara, G., & Gergely, G. (2009). Natural pedagogy. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(4), 148.153.

De Jaegher, H., & Di Paolo, E. (2007). Participatory sense-making. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 6(4), 485–507.

De Jaegher, H. E., Paolo, D., & Gallagher, S. (2010). Can social interaction constitute social cognition? Trends in Cognitive Science, 14(10), 441–447.

De Warren, N. (2009). Husserl and the promise of time. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Donohoe, J. (2004). Husserl on ethics and intersubjectivity: From static to genetic phenomenology. Amherst: Humanity Books.

Ellis, R. (2005). Curious emotions: Roots of consciousness and personality in motivated action. Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Fodor, J., & Pylyshyn, Z. (1981). How direct is visual perception? Some reflections on Gibson’s ‘ecological approach. Cognition, 9(2), 139–196.

Fuchs, T. (2012). “The phenomenology and development of social perspectives”. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, published online.

Gallagher, S. (2005). How the body shapes the mind. New York: Oxford U P.

Gallagher, S. (2008). Direct perception in the intersubjective context. Consciousness and Cognition, 17, 535–543.

Gallagher, S. (2009). Two problems of intersubjectivity. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 16(6–7), 289–308.

Gergely, G., Egyed, K., & Király, I. (2007). On pedagogy. Developmental Science, 10(1), 139–146.

Gibson, J. (1979). The ecological approach to visual perception. New York: Psychology Press.

Gibson, E., & Pick, A. (2000). An ecological approach to perceptual learning and development. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hobson, P. (2002). The cradle of thought. New York: Oxford University Press.

Husserl, E. (1973a). In I. Kern (Ed.), Zur Phänomenologie der Intersubjektivität: Texte aus dem Nachlass, Erster Teil (1905–1920). The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

Husserl, E. (1973b). In I. Kern (Ed.), Zur Phänomenologie der Intersubjektivität: Texte aus dem Nachlass, Zweiter Teil (1921–1928). The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

Husserl, E. (1973c). In I. Kern (Ed.), Zur Phänomanologie der Intersubjektivität: Texte aus dem Nachlass, Dritter Teil (1929–1935). The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

Husserl E. (1973d). Experience and Judgment, L. Landgrebe (Ed.) (trans: Churchill, J. and Ameriks, K.). London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Husserl, E. (1983). Ideas Pertaining to a Pure Phenomenology and to a Phenomenological Philosophy, First Book (trans: Kersten, F.). Dordrecht: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

Husserl, E. (1989). Ideas Pertaining to a Pure Phenomenology and a Pure Phenomenological Philosophy, Second Book (trans: Rojcewicz, R. and Schuwer, A.). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Husserl, E. (1999). Cartesian Meditations: An Introduction to Phenomenology (trans: Cairns, D.). Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Husserl, E. (2001). Analyses Concerning Passive and Active Synthesis: Lectures on Transcendental Logic (trans: Steinbock, A.). Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Husserl, E. (2004). In V. Thomas & G. Regula (Eds.), Wahrnehmung und Aufmerksamkeit: Texte aus dem Nachlass (1893–1912). Dordrecht: Springer.

Husserl, E. (2006). In D. Lohmar (Ed.), Späte Texte über Zeitkonstitution (1929–1934): Die C-Manuskripte. Dordrecht: Springer.

Husserl, E. (2008). In R. Sowa (Ed.), Die Lebenswelt: Auslegungen der vorgegebenen Welt und ihrer Konstitution, Texte aus dem Nachlass (1916–1937). Dordrecht: Springer.

Hutto, D. (2008). Folk psychological narratives. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Iribarne, J. (1994). Husserls Theorie der Intersubjektivität. Munich: Karl Alber Publishing.

Krueger, J. (2013). Ontogenesis of the socially extended mind. Cognitive Systems Research, 25–26, 40–46.

Kühn, R. (1998). Husserls Begriff der Passivität. Munich: Karl Alber Publishing.

Lee, N. (1993). Edmund Husserls Phänomenologie der Instinkte. Dordrecht: Springer.

Lee, N. (2002). “Static-phenomenological and genetic phenomenological concept of primordiality in Husserl’s fifth cartesian meditation. Husserl Studies, 18, 165–183.

Mensch, J. (1988). Intersubjectivity and transcendental idealism. Albany: SUNY Press.

Mensch, J. (2010). Husserl’s Account of Our consciousness of time. Milwaukee: Marquette University Press.

Noë, A. (2004). Action in perception. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Panksepp, J. (1998). Affective neuroscience. New York: Oxford University Press.

Reddy, V. (2008). How infants know minds. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Rochat, P. (2004). Emerging Co-awareness. In G. Bremner & A. Slater (Eds.), Theories of infant development (pp. 258–283). Malden: Blackwell.

Rodemeyer, L. (2006). Intersubjective temporality: It’s About time. Dordrecht: Springer.

Rodríguez, C., & Moro, C. (2008). Coming to agreement: Object use by infants and adults. In J. Zlatev, T. Racine, C. Sinha, & E. Itkonen (Eds.), The shared mind: Perspectives on intersubjectivity (pp. 89–114). Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Rowlands, M. (2010). The New science of the mind: From extended mind to embodied phenomenology. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Russell, M. (2006). Husserl: A guide for the perplexed. New York: Continuum Publishing.

Sheets-Johnstone, M. (2000). “Kinetic tactile-kinesthetic bodies: Ontogenetic foundations of apprenticeship learning.”. Human Studies, 23, 343–370.

Sinha, C., & Rodríguez, C. (2008). Language and the signifying object: From convention to imagination. In J. Zlatev, T. Racine, C. Sinha, & E. Itkonen (Eds.), The Shared Mind: Perspectives on Intersubjectivity (pp. 357-378). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Smith, A. D. (2003). Routledge philosophy guidebook to Husserl and the cartesian meditations. New York: Routledge.

Steinbock, A. (2004). Affection and attention: On the phenomenology of becoming aware. Continental Philosophy Review, 37, 21–43.

Stern, D. (1985). The interpersonal world of the infant. New York: Basic Books.

Taguchi, S. (2006). Das problem des ‘Ur-Ich’ bei Edmund Husserl. Dordrecht: Springer.

Thompson, E. (2001). Empathy and consciousness. In E. Thompson (Ed.), Between ourselves: Second person issues in the study of consciousness (pp. 1–32). Charlottesville: Imprint Academic.

Tomasello, M. (2009). Cultural transmissions: A view from chimpanzees and human infants. In U. Schönpflug (Ed.), Cultural transmission: Psychological, developmental, social, and methodological aspects (pp. 33–47). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Trevarthen, C. (1998). The concept and foundations of infant intersubjectivity. In S. Bråten (Ed.), Intersubjective communication and emotion in early ontogeny. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Turveym, M. T., Shaw, R. E., Reed, E. S., & Mace, W. M. (1981). Ecological laws of perceiving and acting: In reply to Fodor and Pylyshyn (1981). Cognition, 9(3), 237–304.

Williams, E., & Kendell-Scott, L. (2006). “Autism and object use: The mutuality of the social and material in children’s develo** understanding and use of everyday objects.”. In A. Costall & O. Dreier (Eds.), Doing things with things (pp. 51–66). Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing.

Wilson, A., & Golonka, S. (2013). Embodied cognition is not what you think it is. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 1–13.

Yamaguchi, I. (1982). Passive Synthesis und Intersubjektivität bei Edmund Husserl. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

Zahavi, D. (1996). Husserl und die tranzendentale Intersubjektivität. Dordrecht: Springer.

Zahavi, D. (1997). Horizontal intentionality and transcendental intersubjectivity. Tijdschrift voor Filosofie, 59(2), 304–321.

Zahavi, D. (2001). Husserl and Transcendental Intersubjectivity: A Response to the Linguistic-Pragmatic Critique (trans: Elizabeth A. Behnke). Ohio: Ohio University Press.

Zahavi, D. (2003). Husserl’s Phenomenology. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Zahavi, D. (2005). Subjectivity and selfhood: Investigating the first-person perspective. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Zawidzki, T. (2013). Mindsha**: A New framework for understanding human social cognition. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Dan Zahavi and Shaun Gallagher for their comments and suggestions on an earlier draft of this paper. I am also grateful to László Tengelyi and Maren Wehrle for their constructive criticism of ideas contained in this paper as I presented them at the “Soziale Erfahrung” conference of the Deutsche Gesellshaft für phänomenologische Forschung in Cologne, September 2013. In addition, I thank the two anonymous referees whose reports importantly helped me clarify the arguments and ideas of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bower, M. Develo** open intersubjectivity: On the interpersonal sha** of experience. Phenom Cogn Sci 14, 455–474 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-014-9346-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-014-9346-2