Abstract

Objectives

Government officials use criminal records as proxies for past conduct to decide who and how to investigate, arrest, charge, and punish. But those records may be racially biased measures of individual behavior. This paper develops a theoretical definition of bias in criminal records in terms of measurement error. It then seeks to provide empirical estimates of racial bias in official arrest records for a broad swath of offenses.

Method

I use official arrest and self-reported crime data from the Pathways to Desistance study to estimate Black-to-white and Hispanic-to-white crime ratios conditional on arrest. I also develop a novel, theory-based empirical test of differential reporting across racial and ethnic groups.

Results

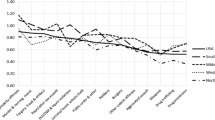

Compared to white subjects with the same number of arrests, I estimate that Black subjects committed 53, 30, 23, and 56% fewer property, violent, drug, and DUI offenses, respectively, and that Hispanic subjects committed 19 and 46% fewer drug and DUI offenses. The analysis finds relatively little evidence of differential reporting that would bias my estimates upwards, with the possible exception of drug trafficking offenses.

Conclusion

The results provide evidence that Pathways subjects’ arrest records are racially biased measures of their past criminal behavior, which could bias decisions of criminal justice officials and risk assessment algorithms that are based on arrest records.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

I use the term “Hispanic” because it is used by the Pathways data.

For a more thorough discussion of the challenges of linking distinct criminal justice records associated with the same person, see Tahamont et al. (2021).

I am grateful to an anonymous reviewer for this point.

As Appendix Fig. 9 shows, the only exception is DUI, in which Black subjects have fewer arrests than white subjects with a similar number of offenses. The estimates for DUI, however, are highly imprecise and statistically insignificant and, as shown in Appendix Tables 2 and 3, these offenses represent a tiny fraction of all arrests.

The NCVS, for example, may undercount white perpetrators if, due to false stereotypes about race and ethnicity, victims are systematically biased towards perceiving a perpetrator is Black or Hispanic. In contrast, police databases that populate the UCR may significantly overcount white (and undercount Hispanic) arrestees, just as administrative correctional records overcount white prisoners (Carson 2018: 7).

Several other papers (e.g., Weaver et al. 2019; Blumstein et al. 2010) study the relationship between self-reported offenses and self-reported arrests (or a combination of self-reported and official arrests), but, for a variety of reasons, measures of self-reported arrests differ substantially from official records (Junger-Tas and Marshall 1999; Pollock et al. 2015) and are thus less suited for a study of measurement error in official arrest records. Another set of papers, not relevant to the current study, examine the relationship between official and self-reported arrests (e.g., Piquero, Schubert and Brame 2014; Krohn et al. 2013).

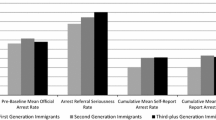

One study measures the proportion of all subjects who reported committing at least one crime who also were arrested at least once, but due to very small sample sizes the estimates are heavily underpowered (Huizinga and Elliot, 1987). A second study, by Piquero and Brame (2008: 12), uses the baseline survey wave of the Pathways study to assess a different question: “whether the racial and ethnic groups in [the] sample … exhibit important differences in prior self-reported delinquency or prior arrests.” The paper primarily tests for differences in the mean and median number of self-reported offenses across racial and ethnic groups, as well as differences in the mean and median number of arrests. One table does, however, report a regression of arrests on race, ethnicity and total number of self-reported offenses. The race and ethnicity coefficients are statistically insignificant, but, in part because the dependent variable is the number of arrests rather than the number of crimes, it’s difficult to translate these results into crime ratios conditional on arrest. Furthermore, the estimates are statistically imprecise because they rely on just one wave of data, the only one available at the time. The current paper addresses this imprecision by using ten additional waves of survey data that have more recently become available.

The unconditional estimator, which is biased, examines the proportion of all subjects of a given racial group who both fail to disclose their drug use and test positive on a urinalysis test. The conditional estimator, which is unbiased, measures the proportion of subjects who do not disclose their drug use among the subset that tested positive.

All datasets used in the study are available through ICPSR at https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/web/NAHDAP/series/260.

Due to small sample sizes, I cannot disaggregate Hispanic subjects into more specific ethnic categories.

Subjects who reported using a specific drug were asked to choose one of the following options to describe the frequency: 1–2 times, 3–5 times, 6–11 times, once per month, two to three times per month, four to five times per month, and everyday. To estimate the number of uses in a given wave, I assume the subject used the minimum value for each category and, when appropriate, multiplied that value by the length of the relevant recall period. To compute an aggregate estimate of drug-use frequency at the person-wave level, I summed the frequency of use for seven drugs: cocaine, opiates, ecstasy, amphetamines, hallucinogens, marijuana, and amyl nitrates.

It is possible the data is missing some arrests due to record sealing but the number is probably very low. Arizona did not seal criminal records during the study period. While Pennsylvania allowed individuals to petition the court to seal, uptake was likely rare (Prescott and Starr 2020) and petitioners typically had to wait a significant period to become eligible. In contrast, Pathways appears to have obtained arrest information quickly. The study website notes: “Agreements with both the juvenile and adult court systems in Phoenix permit data transfer on a daily (juvenile court) or monthly (adult court) basis. In addition, we obtain FBI records…on a yearly basis.” https://www.pathwaysstudy.pitt.edu/codebook/official-record-information.html.

The unclassified arrests are highly heterogeneous, but some of the most common charges are failure to appear, non-DUI driving violations, and illegal weapon carrying.

Almost 75% of the ambiguous violent arrests are for low-level simple assaults, kidnap**, false imprisonment, or broadly defined sexual offenses. Roughly 65% of the ambiguous property arrests are for forgery, trespass and fraud.

As an alternative approach, Appendix Table 5 reports the results of an OLS regression where the dependent variable is the number of self-reported offenses and the independent variables are race and ethnicity interacted with number of arrests. The estimates are similar to Fig. 1; though, they are sometimes statistically imprecise due to small sample sizes and the need to estimate two parameters for each racial or ethnic group—both slope and level parameters. The regressions are also not easily interpretable because racial bias in criminal records could be reflected either in a negative coefficient on the level parameter for Black or Hispanic subjects or in a negative coefficient on the slope parameter for those groups. Moreover, interpreting the magnitude of racial bias depends on a combination of these two coefficients together.

The results are unchanged if I include the binned category.

The sampling distribution is asymmetric because if the number of crimes reported by Black (or Hispanic) subjects is higher than the number reported by white subjects, the crime ratio can go from 1 to infinity, while if the number of crimes reported by white subjects is higher, the estimate can only go from 0 to 1. My results are virtually identical if I use the percentile confidence interval. The confidence intervals are much larger if I use the normal or basic confidence interval because they incorrectly assume a symmetric sampling distribution.

I do not use the fifth month before survey collection in the first six waves or the eleventh month before survey collection in the last four waves because the reporting period for a substantial fraction of the corresponding person-waves contain only five or eleven months, respectively and the first month in every wave is reserved as the post-period for the previous wave.

When a survey was conducted in the second half of a month, the recall period included the month in which the survey took place. For example, if the survey was conducted on July 20th, the subject was asked to report crimes from January through July. The upshot is that self-reported offense data for subjects interviewed in the second half of the month may be incomplete for that month.

I dropped rows corresponding to months falling outside the 7-year study period for each subject and rows associated with missed waves. I also dropped rows to ensure each event has a full pre- and post-period. First, I dropped the first month in each subject’s first wave because these months represent a post-period without any corresponding pre-period. Second, I dropped all but the first month in each of the subjects’ final wave because they represent a pre-period without any corresponding post-period. Third, I drop all pre- and post-period months associated with a small number of events in which—due to a gap in data collection—more than one month elapsed between the last month of the previous wave and the first month of the next wave. Fourth, in the first six waves of the study, I dropped all rows corresponding with pre-period months that were more than four months away from the event and in waves 7 to 9, I dropped all rows corresponding with pre-period months that were more than ten months away from the event. Finally, I dropped the entire pre- and post-period for every event missing at least one month during the pre- or post-period.

The results are similar from a Poisson regression (see Appendix Table 7); though, I omit fixed effects for calendar month-year because the regressions appear unable to estimate standard errors for them in this context.

The results are substantively similar from a Poisson regression (see Appendix Table 9); though, I omit fixed effects for calendar month-year because the regressions appear unable to estimate standard errors for them in this context.

References

Agan A, Starr S (2018) Ban the box, criminal records and racial discrimination. Quart J Econ 133(1):191–235

Atiba Goff P, Barsamian Kahn K (2012) Racial bias in policing. Soc Issues Policy Rev 6(1):177–210

Beck A, Blumstein A (2018) Racial disproportionality in U.S. state prisons. J Quant Criminol 34:853–883

Beck A (2021) Race and ethnicity of violent crime offenders and arrestees, 2018, NCJ 255969

Beckett K, Nyrop K, Pfingst L, Bowen M (2005) Drug use, drug possession arrests, and the question of race: lessons FROM seattle. Soc Probl 52(3):419–441

Berk R, Elzarka A (2020) Almost politically acceptable criminal justice risk assessment. Criminol Public Policy 19(4):1–27

Berk R, Heidari H, Jabbari S, Kearns M, Roth A (2021) Fairness in criminal justice risk assessments: the state of the art. Sociol Methods Res 50(1):3–44

Blumstein A, Nakamura K (2009) Redemption in the presence of widespread criminal background checks. Criminology 47(2):327–359

Blumstein A, Cohen J, Piquero A, Visher C (2010) Linking the crime and arrest processes to measure variations in individual arrest risk per crime (Q). J Quant Criminol 26:533–548

Brame R, Piquero A (2003) Selective attrition and the age-crime relationship. J Quant Criminol 19(2):107–127

Brame R, Fagan J, Piquero A, Schubert C, Steinberg L (2004) Criminal careers of serious delinquents in two cities. Youth Violence Juv Justice 2(3):256–272

Brame R, Turner M, Paternoster R, Bushway S (2012) Cumulative prevalence of arrest from ages 8 to 23 in a national sample. Pediatrics 129(1):21–27

Bureau of Justice Statistics (2010) Criminal victimization in the United States, 2007 statistical tables, NCJ 227669

Carson A (2018) Prisoners in 2016, Revised, NCJ 251149

Caspi A et al (1996) Life history calendar: a research and clinical assessment method for collecting retrospective event-history data. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 6:101–114

D’Alessio S, Stolzenberg L (2003) Race and the probability of arrest. Soc Forces 81(4):1381–1397

Desmarais S, Zottola SA (2020) Violence risk assessment. Marquette Law Rev 103:793–817

Doleac J, Hansen B (2020) The unintended consequences of ‘ban the box’: statistical discrimination and employment outcomes when criminal histories are hidden. J Law Econ 38(2):321–374

Eaglin J (2017) Constructing recidivism risk. Emory Law J 67:59–122

Eckhouse L, Lum K, Conti-Cook C, Ciccolini J (2019) Layers of bias: a unified approach for understanding problems with risk assessment. Crim Justice Behav 46(2):185–209

Efron B, Hastie T (2016) Computer age statistical inference. Cambridge University Press

Elliot D (1995) Lies, damn lies and arrest statistics, Sutherland award presentation.

Engel R, Smith M, Cullen F (2012) Race, place, and drug enforcement. Criminol Public Policy 11(4):603–635

Fagan J, Geller A (2018) Police, race, and the production of capital homicides. Berkeley J Crim Law 23(2):261–313

Falck R et al (1992) The validity of injection drug users self-reported use of opiates and cocaine. J Drug Issues 22:823–832

Farrington D (1986) Age and crime. Crime Justice 7:189–250

Farrington D et al (1996) Self-reported delinquency and a combined delinquency seriousness scale based on boys, mothers, and teachers. Criminology 34(4):493–517

Federal bureau of investigations (2007) Crime in the United States, table 39, https://www2.fbi.gov/ucr/cius2007/data/table_39.html

Federal Bureau of Investigations (2018) “in the United States, table 30, https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2018/crime-in-the-u.s.-2018/tables/table-30

Fendrich M, Yanchun Xu (1994) The validity of drug use reports from juvenile arrestees. Int J Addict 29:971–985

Fendrich M, Mackesy-Amiti ME, Johnson T (2008) Validity of self-reported substance use in men who have sex with men: comparisons with a general population sample. Ann Epidemiol 18(10):752–759

Ferguson A (2017) The rise of big data policing. NYU Press, New York

Fryer R, Levitt S (2004) The causes and consequences of distinctively black names. J Quart Econ 119(3):767–805

Gase LN et al (2016) Understanding racial and ethnic disparities in arrest: the role of individual, home, school, and community characteristics. Race Soc Probl 8:296–312

Geerken M (1994) Rap sheets in criminological research. J Quant Criminol 10:3–21

Gelman A, Fagan J, Kiss A (2007) An analysis of the New york city police department’s ‘stop-and-frisk’ policy in the context of claims of racial bias. J Am Stat Assoc 102(479):813–823

Goel S, Rao J, Shroff R (2016) Precinct or prejudice? Understanding racial disparities in New York city’s stop-and-frisk policy. Ann Appl Stat 10(1):365–394

Goldberger A (1984) Reverse regression and salary discrimination. J Human Resour 19(3):293–318

Golub A, Johnson B, Taylor A, Liberty H (2002) The validity of arrestees’ self-reports: variations across questions and persons. Justice Q 19(3):477–502

Gray TA, Wish ED (1999) Correlates of underreporting recent drug use by female arrestees. J Drug Issues 29(1):91–106

Hardt RH, Peterson-Hardt S (1977) On determining the quality of the delinquency self-report method. J Res Crime Delinq 14:247–261

Hellman D (2019) Measuring algorithmic fairness. Va Law Rev 106(4):811–866

Hindelang M (1978) Race and involvement in common law crimes. Am Sociol Rev 43(1):93–109

Hindelang M, Hirschi T, Weis J (1981) Measuring delinquency. Sage Publications

Hirschi T (1969) The causes of delinquency. University of California Press

Hollinger R (1984) Race, occupational status, and pro-active police arrest for drinking and driving. J Crim Just 12:173–183

Hosser D, Windzip M, Greve W (2008) Guilt and shame as predictors of recidivism: a longitudinal study with young prisoners. Crim Justice Behav 35(1):138–152

Hser Y-I (1997) Self reported drug use: results of selected empirical investigations of validity. In: Harrison L, Hughes A (eds) The validity of self reported drug use; improving the accuracy of survey estimates. National Institute on Drug Abuse, Maryland, pp 320–343

Hser Y-I, Maglione M, Boyle K (1999) Validity of self-report of drug use among STD patients, ER patients, and arrestees. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 25(1):81–91

Huizinga D, Elliot D (1986) Reassessing the reliability and validity of self-report delinquency measures. J Quant Criminol 2(4):293–327

Huizinga D, Elliott DS (1987) Juvenile offenders: prevalence, offender characteristics, and arrest rates by race. Crime Delinq 33(2):206–223

Huq A (2019) Racial equity in algorithmic criminal justice. Duke Law J 68(6):1043–1134

Jacobs J (2015) The eternal criminal record. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Jain E (2015) Arrest as regulation. Stanf Law Rev 67(4):809–867

Johnson W, Petersen R, Wells E (1977) Arrest probabilities for marijuana users as indicators of selective law enforcement. Am J Sociol 83(3):681–699

Jolliffe D, Farrington D, Hawkins D, Catalano R, Hill K, Kosterman R (2003) Predictive, concurrent, prospective and retrospective validity of self-reported delinquency. Crim Behav Mental Health 13:179–197

Junger-Tas J, Marshall IH (1999) The self report methodology in crime research. Crime Justice 25:291–367

Katz C, Webb V, Gartin P, Marshall C (1997) The validity of self-reported marijuana and cocaine use. J Crim Just 25:31–41

Kim JY, Soo MF, Wislar J (2000) The validity of juvenile arrestees’ drug use reporting: a gender comparison. J Res Crime Delinq 37(4):419–432

Kochel TR, Wilson D, Mastrofski S (2011) The effect of suspect race on officers’ arrest decisions. Criminology 49(2):473–512

Krohn M, Waldo G, Chiricos T (1974) Self-reported delinquency: a comparison of structured interviews and self-administered checklists. J Crim Law Criminol 65(4):545–553

Krohn M, Thornberry T, Gibson C, Baldwin J (2010) The development and impact of self-report measures of crime and delinquency. J Quant Criminol 26(4):509–525

Krohn MD, Lizotte A, Phillips M, Thornberry T, Bell K (2013) Explaining systematic bias in self-reported measures: factors that affect the under- and over-reporting of self-reported arrests. Justice Q 30(3):501–528

Lageson S, Denver M, Pickett J (2019) Privatizing criminal stigma: experience, intergroup contact, and public views about publicizing arrest records. Punishment Soc 21(3):315–341

Langan P (1985) Racism on trial: new evidence to explain the racial composition of prisons in the United States. J Crim Law Criminol 76(3):666–683

Lantz B, Wenger M (2020) The co-offender counterfactual. J Exp Criminol 16(2):183–206

Lauritsen J (1998) The age-crime debate: assessing the limits of longitudinal self-report data. Soc Forces 76:1–29

Lauritsen J (2005) Racial and ethnic differences in juvenile offending. In: Darnell H, Kimberly K-L (eds) Our children, their children. University of Chicago Press

Lieberson S, Mikelson K (1995) Distinctive African-American names: an experimental, historical, and linguistic analysis of innovation. Am Sociol Rev 60:928–946

Loeffler C, Hyatt J, Ridgeway G (2019) Measuring self-reported wrongful convictions among prisoners. J Quant Criminol 35:259–286

Lu N, Taylor B, Riley J (2001) The validity of adult arrestee self-reports of crack cocaine use. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 27(3):399–419

Lynch J, Lynn A (2010) Identifying and addressing response errors in self-report surveys. In Piquero A, David W (eds) Handbook of Quantitative Criminology, pp 251–272

Magura S, Goldsmith D, Casriel C, Goldstein P, Lipton D (1987) The validity of methadone clients’ and self-reported drug use. Int J Addict 22:727–749

Maxfield M, Weiler B, Widom C (2000) Comparing self-reports and official records of arrests. J Quant Criminol 16:87–110

Mayson S (2019) Bias in, bias out. Yale Law J 128(8):2218–2300

McElrath K, Dunham R, Cromwell P (1995) Validity of self-reported cocaine and opiate use among arrestees in five cities. J Crim Just 23:531–540

McNagny S, Parker R (1992) High prevalence of recent cocaine use and the unreliability of patient self-report in an inner-city walk-in clinic. J Am Med Assoc 267(8):1106–1108

Meyn I (2021) Race-based remedies in criminal law. William Mary Law Rev 63(1):219–286

Mitchell O, Caudy M (2017) Race differences in drug offending and drug distribution arrests. Crime Delinq 63(2):91–112

Mooney A, Skog A, Lerman A (2022) Racial equity in eligibility for a clean state under automatic criminal record relief laws. Law Soc Rev 56:398–417

Morenoff J (2005) Racial and ethnic disparities in crime and delinquency in the United States. In: Rutter M, Tienda M (eds) Ethnicity and causal mechanisms. Cambridge University Press

Moy L (2021) A taxonomy of police technology’s racial inequity problems. Univ Ill Law Rev 2021(1):139–193

Mukamal D, Samuels P (2003) Statutory limitations on civil rights of people with criminal records. Fordham Urban Law J 30(5):1501–1518

Mulvey E, Carol AS, Alex P (2014) Pathways to desistance—final technical report

National Academy of Sciences (2014) Estimating the incidence of rape and sexual assault. The National Academies Press, Washington

OJJDP (2021) Statistical briefing book. https://www.ojjdp.gov/ojstatbb/crime/ucr.asp?table_in=2&selYrs=2007&rdoGroups=1&rdoData=c

Okidegbe N (2021) Discredited data. Cornell Law Review, forthcoming.

Pathways to desistance (2012) Out of community placements codebook, https://www.pathwaysstudy.pitt.edu/codebook/out_of_community_placements_public_version.pdf

Peters R, Kremlin J, Hunt E (2014) Accuracy of self reported drug use among offenders. Crim Justice Behav 42(6):623–643

Pierson E et al (2020) A large-scale analysis of racial disparities in police stops across the United States. Nat Human Behav 4:736–745

Piquero A, Brame R (2008) Reassessing the race-crime and ethnicity-crime relationship in a sample of serious adolescent delinquents. Crime Delinq 54(3):1–33

Piquero A, Schubert C, Brame R (2014) Comparing official and self-report records of offending across gender and race/ethnicity in a longitudinal study of serious youthful offenders. J Res Crime Delinq 51(4):526–556

Pollock W et al (2015) It’s official: predictors of self-reported vs. official recorded arrests. J Crim Just 43(1):69–79

Porterfield A (1943) Delinquency and outcome in court and college. Am J Sociol 49:199–208

Prescott JJ, Starr SB (2020) Expungement of criminal convictions: an empirical study. Harv Law Rev 133:2460–2555

Rendon A et al (2017) What’s the agreement between self-reported and biochemical verification of drug use? A look at permanent supportive housing residents. Addict Behav 70:90–96

Richardson R, Schultz J, Crawford K (2019) Dirty data, bad predictions. N Y Univ Law Rev Online 94:192–233

Roberts J, Julie H (2010) The life event calendar method in criminological research. In: Piquero A, David W (eds) Handbook of quantitative criminology, pp 289–312

Rojek D (1983) Social status and delinquency: do self-reports and official reports match. In: Waldo GP (ed) Measurement issues in criminal justice. Sage, Beverly Hills

Rosay A, Najaka SS, Herz D (2007) Differences in the validity of self-reported drug use across five factors: gender, race, age, type of drug, and offense seriousness. J Quant Criminol 23:41–58

Schubert C et al (2004) Operational lessons from the pathways to desistance project. Youth Violence Juv Justice 2(3):237–255

Short J, Nye I (1957) Reported behavior as a criterion of deviant behavior. Soc Probl 5(3):207–213

Skeem J, Lowenkamp C (2016) Risk, race, and recidivism: predictive bias and disparate impact. Criminology 54(4):680–712

Smith D, Visher C, Davidson L (1984) Equity and discretionary justice: the influence of race on police arrest decisions. J Crim Law Criminol 75(1):234–249

Snyder H (2011) Arrest in the United States 1980–2009, NCJ 234319

Sohoni T, Ousey G, Bower E, Mehdi A (2021) Understanding the gap in self-reported offending by race: a meta-analysis. Am J Crim Justice 46:770

Stevenson M (2018) Assessing risk assessment in action. Minnesota Law Rev 103:303–384

Stolzenberg L, D’Alessio S, Flexon J (2021) The usual suspects: prior criminal record and the probability of arrest. Police Q 24(1):31–54

Tahamont S, Jelveh Z, Chalfin A, Yan S, Hansen B (2021) Dude, where’s my treatment effect? Errors in administrative data linking and the destruction of statistical power in randomized experiments. J Quant Criminol 37:715–749

Thacher D (2011) The distribution of police protection. J Quant Criminol 27:275–298

Thornberry T, Marvin K (2003) Comparison of self-report and official data for measuring crime. In: Measurement problems in criminal justice research, National Academies Press, Washington

Thornberry T (1989) panel effects and the use of self-reported measures of delinquency in longitudinal studie. In Klein MW (eds) Cross-national research in self-reported crime and delinquency, pp 347–369

Tonry M (1995) Malign neglect. Oxford University Press, New York

United States Department of Justice (2011) Criminal victimization in the United States, 2008 statistical tables, NJC 231173

Weaver V, Papachristos A, Zanger-Tishler M (2019) The great decoupling: the disconnection between criminal offending and experience of arrest across two cohorts. RSF J Soc Sci 5(1):89–123

Webb V, Katz C, Decker S (2006) Assessing the validity of self-reports by gang members: results from the arrestee drug abuse monitoring program. Crime Delinq 52(3):232–252

Yang C, Dobbie W (2021) Equal protection under algorithms: a new statistical legal framework. Mich Law Rev 119(2):291–396

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author has no relevant financial or non-financial interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

I would like to thank Brandon Garrett, Lisa Griffin, Aziz Huq, Sandra Mayson, John Rappaport, Megan Stevenson, and three anonymous reviewers for helpful comments and feedback.

Appendix

Appendix

See Figs. 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11, and Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Grunwald, B. Racial Bias in Criminal Records. J Quant Criminol (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-023-09575-y

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-023-09575-y