Abstract

Purpose

This study examines the relationship between mental illness diagnoses and four intergenerational patterns of child protection services involvement: cycle breakers, cycle maintainers, cycle initiators, and a comparison group (no maltreatment). Existing research is limited and inconsistent, and rarely incorporates multiple categories of mental illness or considers variation between mental illnesses.

Methods

Data were drawn from an administrative population-based data repository in Queensland, Australia and includes 32,494 individuals identified as biological parents. Child protection data were obtained from the Department of Children, Youth Justice and Multicultural Affairs and mental illness diagnoses were obtained from Queensland Health hospital admissions. Any mental illness diagnosis, age at onset (adolescence or adulthood), and diagnosis types (common, severe, personality disorders, childhood-onset, adolescent- and adult-onset, and substance use) were examined. Multinomial and logistic regressions were conducted to investigate whether the mental illness diagnosis variables distinguished the four intergenerational patterns of child protection service involvement.

Results

Overall, 10.4% of individuals had at least one hospital admission involving a mental illness diagnosis. The prevalence of mental illness diagnoses significantly differed across the intergenerational patterns. Cycle maintainers and cycle initiators received the highest rates of diagnoses (50% and 38.8%, respectively), compared to cycle breakers (21.1%) and the comparison group (7.7%).

Conclusions

Our findings underline the need for early access to mental health supports for families involved with the child protection system, which could help prevent the cycle of maltreatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Half of depression and anxiety cases worldwide may be attributable to child maltreatment victimization (Li et al., 2016). Furthermore, 22% to 80% of parents involved in the child protection system (CPS) are estimated to have experienced mental illness (Higgins et al., 2021). Despite this, minimal research has examined mental illness in the context of intergenerational child maltreatment. Specifically, little research has examined the four distinct pathways of (dis)continuity: cycle breakers (individuals with a maltreatment victimization history who are not subsequently responsible for maltreatment to a child), cycle maintainers (individuals with a maltreatment victimization history who are subsequently responsible for maltreatment to a child), cycle initiators (individuals with no maltreatment victimization history who are responsible for maltreatment to a child), and a comparison group (no maltreatment). Moreover, we know little about whether the relationship between mental illness and child maltreatment varies based on age at onset or type of mental illness, which is largely due to methodological limitations, such as small sample sizes that preclude disaggregation. Thus, our aim is to examine mental illness diagnoses (including onset age and types) and intergenerational patterns of child protection services involvement using longitudinal population-based linked administrative data from Queensland (QLD), Australia.

The link between mental illness and child maltreatment is well established (Kaplan et al., 2019; Li et al., 2016). Some theorists posit that experiencing trauma, such as child maltreatment victimization, may disrupt neurobiological and psychological development (Doom & Cicchetti, 2020). These disruptions can result in heightened stress responses and impeded co** abilities, reduced cognitive functioning, dysregulated emotions, and attachment and relationship difficulties, which subsequently increase the risk of long-term psychopathology (Doom & Cicchetti, 2020). Some explanations for the increased risk of maltreatment occurring in families with parental mental illness suggest that experiencing mental illness may result in less responsive parenting practices, disrupted attachment and interaction between the parent and child/ren, failure to appropriately meet a child’s needs, maladaptive responses to stressful circumstances, and reduced safety awareness/behaviors (Whitten et al., 2021). Moreover, mental illness is linked with several other environmental risk factors related to child maltreatment. For example, families experiencing mental illness are also likely to experience socio-economic disadvantage, domestic and family violence (DFV), and have fewer social supports (Roscoe et al., 2021). Importantly, there is heterogeneity in these associations; many individuals with a victimization history will not develop a mental illness (Doom & Cicchetti, 2020), and many individuals with a mental illness will not be responsible for maltreatment to a child (McEwan & Friedman, 2016). Similarly, we know that many individuals with a victimization history will not continue the cycle of maltreatment (McKenzie et al., 2021). What remains unclear is the association between mental illness and the distinct intergenerational patterns of CPS involvement.

The small body of research examining mental illness and intergenerational patterns of child maltreatment yields inconsistent findings. Arguably, the use of different data sources and definitions of child maltreatment and/or mental illness contribute to some variance across studies. How these variables are measured (i.e., self-report or official data; period of time (one week or lifetime); maltreatment subtypes or mental illness types included) will influence who is identified as experiencing either child maltreatment or mental illness. Some studies suggest that depression (Choi et al., 2019) or any mental illness (Dixon et al., 2005) are associated with increased risk of maltreatment continuity. For example, among mothers who experienced out-of-home care, a history of any documented mental illness characterized those most at risk for CPS contact as a person responsible for maltreatment to a child (Eastman & Putnam-Hornstein, 2019). In contrast, a study involving 499 pregnant women found that self-reported depression or anxiety in the past year were significantly associated with a self-reported history of maltreatment victimization, however, these illnesses were not associated with subsequent maltreatment perpetration (Berlin et al., 2011). Some findings suggest an inverse relationship. To illustrate, Pears and Capaldi (2001) reported that higher depression and post-traumatic stress disorder scores (based on self-report measures) were associated with less risk of maltreatment continuity for physical abuse. Inconsistent findings have also emerged regarding substance use. Some research links self-reported substance use with the maltreatment continuity (Jaffee et al., 2013), while others report no relationship between self-reported substance use and maltreatment continuity for physical abuse (Capaldi et al., 2019).

Findings also vary for the studies that have examined all four intergenerational patterns of maltreatment (i.e., cycle breakers, cycle maintainers, cycle initiators, and a comparison group). Dixon et al. (2009) identified that a self-reported history of treatment for mental illness and/or substance use were higher among parents categorized as cycle maintainers, breakers, and initiators, compared to a control group. However, no differences were found between any combinations of the three maltreatment groups (Dixon et al., 2009). Similarly, in their sample of 193 mother-child dyads, St-Laurent et al. (2019) found that self-reported level of psychological distress did not significantly distinguish cycle maintainers and breakers. Psychological distress also did not distinguish cycle breakers or initiators from the control group (St-Laurent et al., 2019). A third study, focusing on sexual abuse among 196 mother-child dyads, examined self-reported substance use and trauma symptomatology, which consisted of six subscales, including anxiety and depression (Leifer et al., 2004). Cycle maintainers and initiators significantly differed from the control group for substance use, anxiety, and depression, however, cycle breakers did not (Leifer et al., 2004). Moreover, there were no significant differences between cycle maintainers and initiators (Leifer et al., 2004), indicating similar risk profiles. In sum, the variance across findings means we lack clarity regarding the association between mental illness and maltreatment (dis)continuity.

Consistent with the wider child maltreatment literature, most intergenerational maltreatment research on mental illness has focused on any mental illness (i.e., aggregating all types of mental illness together) or has been limited to depression and/or substance use. Given that depression is one of the most prevalent mental illnesses in the general community (Li et al., 2016), it is unsurprising that this illness has received considerable attention. However, a recent study utilizing a representative community sample of 364 parents and their adult children (n = 573) found that borderline personality disorder (assessed across time via clinician, self, and informant reports) was associated with self-reported maltreatment across two generations (Paul et al., 2019). Therefore, it may be important to also consider lower prevalence mental illnesses in relation to intergenerational patterns of maltreatment. Similarly, child maltreatment victimization has been associated with an increased risk of personality disorders, schizophrenia and childhood-onset disorders (e.g., Maclean et al., 2019), which have also been associated with an increased risk of CPS involvement as a person responsible for maltreatment to a child (e.g., O'Donnell et al., 2015).

A recent meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies highlighted the importance of age at onset of mental illness, rather than just absence or presence (Solmi et al., 2022). No known studies examining the four distinct intergenerational patterns of child maltreatment have considered onset of mental illness. Although some research has examined broader concepts of timing. For example, a study on child maltreatment perpetration identified that adolescent-onset mental illness (<18 years) was not significantly associated with the perpetration of maltreatment in multivariate analyses, however, mental illness during adulthood remained significant (Ben-David et al., 2015). Further exploration of the overlaps between mental illness diagnoses and intergenerational patterns of maltreatment variations, with consideration of timing of mental illness (i.e., age at onset), is warranted.

Overall, existing research is characterized by inconsistent operationalization and measurement of mental illness, meaning we lack clarity regarding associations between mental illness and intergenerational patterns of child maltreatment. For example, studies have differed in the time periods used to identify the absence/presence of a mental illness, including the past week (e.g., St-Laurent et al., 2019), past year (e.g., Capaldi et al., 2019), and lifetime (e.g., Jaffee et al., 2013). Studies also generally utilize relatively small samples, retrospective methodologies, and short follow-up periods (e.g., Leifer et al., 2004; St-Laurent et al., 2019). Our study complements existing research by using prospective longitudinal data from two birth cohorts that included 32,494 individuals. Using administrative data, we explore mental illness diagnoses resulting from hospital admissions across the intergenerational patterns of CPS involvement; cycle breakers, cycle maintainers, cycle initiators, and a comparison group (no maltreatment). Moreover, we examine age at onset and types of mental illness diagnoses to elucidate nuances in these associations.

Method

Data Source

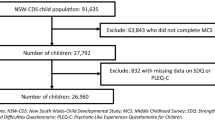

Data for this study were drawn from the QLD Cross-Sector Research Collaboration (QCRC) data repository (see McKenzie et al., 2021; Stewart et al., 2020). QLD is the third most populous state in Australia, with 5.2 million residents (20% of the Australian population) (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2022). Four percent of the QLD population identify as Australia’s First Nations people (hereafter referred to as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples) (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2022). The data repository includes state-wide de-identified linked records on all individuals born in 1983 and 1984 who had any contact with multiple QLD government agencies, spanning child maltreatment, justice, and health. Data extractions were conducted between 2013 and 2015 when individuals were aged 29/30/31/32 years. For this study, we utilized demographic data from the QLD Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, child maltreatment data from the QLD Department of Children, Youth Justice and Multicultural Affairs (QLD CPS), and hospital admissions data from QLD Health. Our sample included all individuals who were born in QLD, were registered as a biological parent via birth records, and had not died ≤30 years old. We cut the observation period at 30 years so that intergenerational child maltreatment was examined for equivalent periods across the 83/84 cohorts.

Record linkage was completed using probabilistic linkage methods. QLD Health undertook the linkage of the health datasets and the QLD Government Statistician’s Office linked all other agency datasets. The QLD Government Statistician’s Office subsequently linked the pre-linked QLD Health data with the pre-linked social/justice data to provide the final linked dataset. This study has ethical approval from the University’s Human Research Ethics Committee (2020/058) and approval was granted by the government data custodians.

Sample

There were 32,494 parents in our sample (44.5% males, 9.9% Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples). On average, cohort individuals were 24.3 years old at the birth of their first child (SD = 3.8, IQR: 21, 27). According to Thornberry et al. (2012), strong methodological studies require a minimum five-year observation period in the second generation. In our sample, 56.5% of first-born children were aged five years and older (M = 5.7, SD = 3.8, Md = 5.0, IQR: 3, 9).

Measurements

Child Maltreatment

Maltreatment experiences of cohort individuals as a victim and/or person responsible for harm to a child were obtained from the QLD CPS integrated client management system. These data incorporate all contacts between 1983 and 2015.

Child Maltreatment (Victim)

First generation maltreatment was measured as a CPS record of harm and/or risk of harm where the cohort individual was identified as the subject child (0–17 years). Both unsubstantiated and substantiated notifications of harm were included. First generation maltreatment was computed as a binary variable (yes; no).

Child Maltreatment (Person Responsible)

Second generation maltreatment was measured as a CPS record where the cohort individual was identified as the person responsible for harm and/or risk of harm to a child. Second generation maltreatment included substantiated events since that is the only data available in the QCRC repository. QLD CPS data records the person who is identified as responsible for acts of commission, omission, or failure to protect. If an event involved more than one cohort individual, each individual identified as responsible for harm/risk of harm would be recorded. Any contacts as a person responsible for harm when aged ≤30 years old were included. Second generation maltreatment was computed as a binary variable (yes; no).

Intergenerational Maltreatment Group

Consistent with existing literature (e.g., Jaffee et al., 2013), the life-course (0–30 years) experiences of cohort individuals were assigned to one of four intergenerational maltreatment groups: cycle breakers (contact with CPS as a child victim only), cycle maintainers (contact with CPS as a child victim and person responsible for harm to a child), cycle initiators (contact with CPS as a person responsible for harm to a child only), and a no maltreatment group (no contact with CPS).

Mental Illness

Data regarding mental illness diagnoses of cohort individuals were obtained from the Queensland Hospital Admitted Patient Data Collection (QHAPDC). These data include individuals who received a mental illness diagnosis (as a principal or secondary diagnosis) during a hospital admission that was subsequently coded according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10; World Health Organization, 2004). Individuals could experience multiple hospital admissions and receive multiple diagnoses across the observation period. The current QHAPDC records were not available prior to July 1995; consequently, data are left-censored from birth to age 11/12 and 10/11 years for the 1983 and 1984 cohorts, respectively. QHAPDC separations to June 2014 are available in the QCRC data repository, when individuals were aged 29/30/31 years. Any hospital admissions involving a mental illness diagnosis when the individual was aged ≤30 years were included in this study. Due to the extraction date, data are right-censored at age 29 for some individuals born in 1984. Thus, data reflects life-course prevalence of mental illness based on hospital admissions for individuals from 10/11/12 years to 29/30 years.

Any Mental Illness

Any mental illness was computed as a binary variable according to whether an individual ever received a mental illness diagnosis based on the following criteria: ICD-10 mental and behavioural disorders (codes F00 to F99), suicidal ideation (code R45.8), and self-harm (codes X60 through X84) (present; absent).

Mental Illness Types

Six categories of mental illnesses were created: (1) common mental disorders; (2) severe mental disorders; (3) personality disorders; (4) adolescent and adult-onset disorders; (5) childhood-onset disorders; and (6) substance use disorders (SUDs), excluding substance-induced psychoses that are categorized as severe mental disorders (see Supplementary Table 1 for details of diagnoses and ICD-10 codes). While these categories contain mutually exclusive disorders, it is possible for an individual to be assigned to multiple categories if an individual ever received more than one diagnosis under different categories. All categories were computed as binary variables (present; absent).

Age at Onset of Mental Illness

Age at onset of mental illness was computed using the individual’s birth date and the date of the first hospital admission that involved a mental illness diagnosis. A categorical variable was created for each cohort individual for age at onset of mental illness: (1) no diagnosis; (2) adolescence (10/11/12 to 17 years) and (3) adulthood (18 to 29/30 years).

Confounders

The following variables were included as confounders due to their associations with child maltreatment. Age at first child’s birth was computed using the cohort individual’s birth date and their first child’s birth date. Number of biological children was computed as a categorical variable (1–2 children; ≥3 children). These categories were based on existing child maltreatment literature that indicates increased risk for maltreatment occurring in families with three or more children (e.g., McKenzie et al., 2021). Sex was computed as a binary variable (male; female). Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander status was computed as a binary variable (yes; no). In Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have an almost seven-fold increased risk of contact with the CPS compared to non-Indigenous people (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2020). In line with best practice guidelines when using linked administrative data in Australia (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2012), if a cohort individual was ever recorded as an Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander person across any QCRC dataset, they were classified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander, but if information on Indigenous status was not available, the individual was classified as non-Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander.

Analytical Strategy

Data analyses were performed using SPSS version 28.0, except for the cumulative prevalence analysis, which was performed using R version 4.2.0. Descriptive statistics, cumulative prevalence, bivariate, and multivariable analyses were conducted to explore the associations between mental illness variables and intergenerational (dis)continuity of CPS involvement. Cumulative prevalence of mental illness diagnoses were measured as the proportion of individuals within each maltreatment group experiencing their first mental illness diagnosis from a hospital admission up to age 30 years and was modelled using the survival package for R (version 3.3–1; Therneau, 2022). Differences in cumulative prevalence rates among groups were examined using Gray (1988) test. Intercorrelations between all mental illness and demographic variables were examined prior to multivariable analyses (see Table 1). The majority of intercorrelations were small (r = .01–.30), however, there were medium to strong correlations among any mental illness, age at onset of mental illness, and the mental illness types. Therefore, three separate multinomial regressions were conducted (any mental illness diagnosis, age at onset, and the six mental illness types) with the full sample (n = 32,494) to assess whether these mental illness variables distinguished the four maltreatment groups, with the no maltreatment group as the reference group. Logistic regressions were then performed limited to the maltreatment groups (i.e., excluding the no maltreatment group) for any mental illness diagnosis and for age at onset to compare: (1) cycle breakers and cycle maintainers (n = 2916); (2) cycle breakers and cycle initiators (n = 3112); and (3) cycle initiators and cycle maintainers (n = 1556). A total of six logistic regressions were performed (three for any mental illness diagnosis and three for age at onset). Due to the reduced sample size, logistic regressions limited to the maltreatment groups including all six mental illness types could not be conducted as they were unstable. However, logistic regressions were conducted for the two most prevalent mental illness types.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Sample descriptives for the total sample stratified by intergenerational maltreatment group are provided in Table 2. Overall, 10.4% (n = 3367) of cohort individuals had at least one hospital admission involving a mental illness diagnosis by 30 years of age. When separated by intergenerational maltreatment group, our findings indicated an increasing trend for the prevalence of mental illness diagnoses across the groups as follows: no maltreatment < cycle breakers < cycle initiators < cycle maintainers [χ 2 = (3, n = 32,494) = 2407.88, p < .001, φ = .27]. To highlight, by the age of 30 years 50.0% of individuals identified as cycle maintainers received at least one mental illness diagnosis compared to 7.7% of individuals in the no maltreatment group. The majority of diagnosis types followed the same increasing trend across the maltreatment groups, with substance use disorders being the most prevalent type for all groups. The prevalence of adolescent-onset mental illness was relatively similar for cycle breakers and cycle initiators and the prevalence of adult-onset mental illness was similar for cycle initiators and cycle maintainers.

The likelihood of being an Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander person, and having three or more children, increased across maltreatment groups mirroring the same pattern observed for mental illness diagnoses above of no maltreatment < cycle breakers < cycle initiators < cycle maintainers. In contrast, the mean age of an individual at time of first child’s birth decreased across maltreatment groups as follows: no maltreatment > cycle breakers > cycle initiators > cycle maintainers. Generally, similar patterns were observed for descriptive statistics when examined for males and females separately (see Supplementary Tables 2 and 3).

Figure 1 displays the cumulative prevalence in years of first mental illness diagnosis from a hospital admission stratified by intergenerational maltreatment group. Significant differences in cumulative prevalence rates across the maltreatment groups were observed: (χ 2 (3, 32,494) = 2475.38, p < .001). Cycle maintainers had the highest cumulative prevalence rates across age compared with all other maltreatment groups, and the no maltreatment group consistently had the lowest. Cycle breakers and initiators had similar prevalence rates of being diagnosed with a mental illness until late adolescence/early adulthood, after which cycle initiators had an increasing prevalence of being diagnosed with a mental illness until age 30 years compared to cycle breakers.

Mental Illness Diagnoses Across Intergenerational Maltreatment Groups

Three separate multinomial regression models were conducted to examine whether the mental illness variables (i.e., any, age at onset, and type) differentiate the three maltreatment groups from the no maltreatment group after controlling for sex, Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander status, number of biological children, and age at first child (see Table 3). All models were statistically significant. Model 1 (any mental illness diagnosis) results indicated that cycle breakers, cycle initiators, and cycle maintainers all had higher odds of any mental illness diagnosis compared to the no maltreatment group. A clear pattern emerged across the maltreatment groups. The magnitude of the associations increased in the pattern no maltreatment < cycle breakers < cycle initiators < cycle maintainers.

When we separated any mental illness diagnosis by age at onset (Model 2), the same pattern from Model 1 emerged for adult-onset: no maltreatment < cycle breakers < cycle initiators < cycle maintainers. However, while all three maltreatment groups had higher odds of adolescent-onset, compared to the no maltreatment group, cycle breakers and cycle initiators had similar magnitude of ORs. Model 3 (mental illness types) indicated that most of the diagnosis types remained important in differentiating each maltreatment group from the no maltreatment group, when accounting for all other diagnoses and the confounders. However, different patterns emerged across the maltreatment groups. Cycle breakers had four times higher odds of a childhood-onset disorder compared to the no maltreatment group. In contrast, severe and personality disorders were not significant when accounting for other types of mental illness and the confounders. Cycle maintainers had over seven times higher odds of a childhood-onset disorder compared to the no maltreatment group, while a severe disorder was not significant when accounting for other types of mental illness and the confounders. All types of mental illness diagnoses were significant for differentiating cycle initiators from the no maltreatment group. Cycle initiators and cycle maintainers both had large ORs for substance use compared to the no maltreatment group.

Mental Illness Limited to the Three Maltreatment Groups

Six logistic regressions were conducted (three for any mental illness diagnosis and three for age at onset) limited to the maltreatment groups to compare patterns of mental illness between: (1) cycle breakers and cycle maintainers; (2) cycle breakers and cycle initiators; and (3) cycle initiators and cycle maintainers (see Table 4). All logistic regressions controlled for sex, Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander status, number of biological children, and age at first child. The findings for any mental illness diagnosis followed the same pattern observed in the previous analyses. Cycle maintainers had over three times higher odds of any mental illness diagnosis compared to breakers. Cycle maintainers also had 1.5 times higher odds of any mental illness diagnosis compared to initiators. Cycle initiators had over two times higher odds of any mental illness diagnosis compared to breakers.

When any mental illness was separated further by age at onset, findings followed the same pattern observed in the previous analyses. Cycle maintainers had higher odds of experiencing adolescent- and adult-onset mental illness compared to breakers. Cycle maintainers also had higher odds of experiencing adolescent- and adult-onset mental illness compared to initiators. Cycle initiators had higher odds of experiencing adult-onset mental illness compared to breakers, however, adolescent-onset mental illness was not significant.

Separate logistic regressions were also conducted for the two most prevalent mental illness diagnosis types (i.e., common disorders and substance use disorders) and full results are provided in Supplementary Table 4. The patterns and magnitudes of association for these two types of mental illness diagnoses are in line with the results for the logistic regressions on any mental illness diagnosis. Cycle maintainers had the largest odds ratios for both types of mental illness diagnoses compared to the other two groups. For example, cycle maintainers had over three times higher odds of being diagnosed with a common disorder or a substance use disorder compared to breakers. Cycle initiators also had higher odds ratios compared to breakers; specifically, they had two times higher odds of being diagnosed with a common disorder and almost 2.5 times higher odds of being diagnosed with a substance use disorder compared to breakers.

Discussion

Our study both confirms existing findings and provides new knowledge and nuanced understanding of the links between intergenerational (dis)continuity of CPS involvement and mental illness diagnoses. Our results support existing literature indicating that mental illness is generally more prevalent among individuals who have had contact with CPS. We extend existing literature by highlighting differences in terms of risk for any mental illness diagnosis, and nuances in the age at onset and types of diagnoses for cycle breakers, cycle maintainers, and cycle initiators.

In our sample, almost 40% of cycle initiators, and 50% of cycle maintainers, experienced a mental illness diagnosis, indicating significant vulnerability among individuals who have contact with the CPS as a person responsible for maltreatment, irrespective of a maltreatment victimization history. In contrast, 21% of cycle breakers and just 7% of individuals with no CPS contact experienced a mental illness diagnosis. The finding for cycle maintainers is unsurprising, given the extent of research that has focused on these individuals in the intergenerational literature. However, the finding for cycle initiators warrants further discussion given these individuals are relatively under-studied. Some prior findings for mental illness suggest that cycle maintainers and cycle initiators do not significantly differ from each other (e.g., Dixon et al., 2009). Other research has indicated that cycle initiators are often characterized by the same cumulative adversities as cycle maintainers, such as young parenting, a large family, social isolation, financial hardship, and DFV (e.g., McKenzie et al., 2021; St-Laurent et al., 2019), thereby creating similar risk profiles. In our sample, cycle maintainers had an elevated risk of receiving a mental illness diagnosis compared to cycle initiators; a finding that remained after controlling for other risk factors. However, the high prevalence and higher odds of receiving a mental illness diagnosis among cycle initiators, compared to cycle breakers and the comparison group, is an important finding. It is possible that contact with CPS as a person responsible (i.e., cycle maintainers or initiators) was attributable to receiving a mental illness diagnosis during a hospital admission. That is, individuals may have been subsequently reported to CPS due to serious mental illness and/or other concerns. Future research should consider the timing of service contacts to understand the extent of CPS involvement as a result of health services contact. Nonetheless, these findings also reiterate the importance of examining risk factors beyond victimization history in attempting to develop and target maltreatment prevention and intervention policies and practice.

It is important to highlight that there was a substantial degree of discontinuity evident in our study. Over 75% of individuals who experienced a maltreatment victimization history were not subsequently held responsible for maltreatment to a child. However, individuals categorized as cycle breakers did still have a higher prevalence of receiving a mental illness diagnosis compared to the no maltreatment group. Conversely, the lower prevalence of receiving a mental illness diagnosis among cycle breakers, compared to those individuals identified as responsible for maltreatment (i.e., cycle initiators and cycle maintainers), suggests the presence of other factors (i.e., resilience/protective factors). Future research should explore this further to identify factors that may aid in reducing both child maltreatment and mental illness.

Our findings on age at onset suggest that the same general patterns exist across maltreatment groups, regardless of timing. However, some nuances emerged. Cycle maintainers had significantly higher odds of receiving their first mental illness diagnosis during adolescence, compared to cycle initiators. It is possible that cycle maintainers are at higher risk of a diagnosis during adolescence as a direct result of their maltreatment victimization experiences. Psychopathology is a well-documented outcome of trauma (Doom & Cicchetti, 2020). On a similar note, given these individuals are already engaged with a service (i.e., CPS), there is a heightened chance that any indication of mental illness will be observed and these individuals referred to hospital.

Our comparison of cycle breakers and cycle initiators suggests that there are factors contributing to an increase in risk for cycle initiators specifically during adulthood that do not appear to be present for cycle breakers. However, the prevalence of receiving their first mental illness diagnosis during adolescence was the same for cycle breakers and cycle initiators, and higher than the no maltreatment group, which does still indicate a heightened level of risk for adolescent mental illness among individuals who become involved with the CPS as a person responsible for maltreatment, in the absence of a victimization history. Future research should explore other childhood/adolescent experiences that may contribute to the development of mental illnesses among this population.

Our findings for mental illness type, overall, revealed that most types retained importance when accounting for all other types and the confounders, across the three maltreatment groups. These findings may be explained by the notion that there are shared psychopathological features underpinning mental illnesses, making it less about the type of mental illness as opposed to the general level of psychopathology (Chang et al., 2015; DeLisi et al., 2022). Interestingly, while personality disorders did retain significance for cycle maintainers when accounting for all other mental illness types and the confounders, personality disorders did not retain significance for cycle breakers. This was unexpected, given prior research has typically indicated a strong association between traumatic experiences, such as maltreatment victimization (all subtypes), and develo** personality disorders (Maclean et al., 2019). In our study, personality disorders were more prevalent among cycle maintainers compared to cycle breakers (10% versus 2.2%, respectively). These results indicate that there may be other factors reducing the risk of cycle breakers experiencing personality disorders, despite their victimization history; a finding that needs to be explored in future research.

Substance use was prominent among all three maltreatment groups, with cycle maintainers and cycle initiators at particularly high risk. In both of these groups, approximately 70% of individuals who received a mental illness diagnosis were diagnosed with a substance use disorder. Our results support prior research identifying higher substance use among cycle maintainers and cycle initiators, compared to the no maltreatment group (Dixon et al., 2009; Leifer et al., 2004). Moreover, substance use has been well-documented as a risk factor for disproportionate child protection involvement as a person responsible for maltreatment (Freisthler et al., 2017). Alternatively, substances are often used to self-medicate as a way of co** with trauma or stress (Mills et al., 2006), meaning substance use may be indicative of more pervasive issues that are independently contributing to risk. Given the prevalence of substance use among the families in our study, evidence-based treatment resources for individuals involved with CPS are needed.

It is important to acknowledge that the increasing prevalence of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander individuals across maltreatment groups (no maltreatment < cycle breakers < cycle initiators < cycle maintainers) is consistent with ongoing disproportionate representation in the CPS. Existing research has documented the marked vulnerability of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with regard to increased risk of CPS involvement (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2020) and mental illness (Ogilvie et al., 2021). Likewise, the mechanisms underlying these increased risks are increasingly being acknowledged, including a history of colonization, trauma and discrimination, social and economic disadvantage, systemic racism and concerns regarding inappropriate service provision (Newton, 2019; Watego et al., 2021). While not a focus of this study, it is acknowledged that research focusing on the experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, using culturally appropriate research methods, is needed.

Study Strengths and Limitations

A notable strength of this study is the use of a large, representative, population-based sample of over 32,000 individuals, which provided an opportunity to examine life-course experiences (0–30 years) among two at-risk populations in our community. Families such as these are often difficult to engage in research studies (Chikwava et al., 2021). Moreover, we could identify those individuals who have service usage across multiple government departments, which provides opportunities for informing intervention targets. The size of our sample provided sufficient statistical power to examine rare outcomes, such as less prevalent types of mental illnesses.

The use of official data provides a conservative estimate of child maltreatment and mental illness in the population. In addition to many instances of child maltreatment not being reported, our reliance on substantiated events for second generation maltreatment means there are likely additional CPS contacts (i.e., unsubstantiated events as a person responsible) that are not captured in our study. Likewise, given that mental illness diagnoses were derived from hospital admissions, they will be biased toward more severe/acute presentations. The use of hospital records means data are left censored at age 10/11/12 years and right censored at age 29/30 years. Therefore, we cannot account for initial contacts for mental health diagnoses occurring after this time. Future research should explore mental illness and intergenerational patterns of child maltreatment further into the life course.

In our CPS data, the person identified as responsible for harm to a child is typically the parent/caregiver, meaning it is unclear whether the individual perpetrated the maltreatment or “failed to protect” the child from someone else. Our measurement of cycle initiators and cycle maintainers reflects whether the individual had CPS contact due to being held responsible for an omission, commission or failure to protect. Our data cannot account for migration out of QLD; an issue pertinent to child maltreatment research as housing instability and transience may be linked to child protection involvement (Marcal, 2018). The age of the second-generation children (children born to the cohort individuals) varies; thus, we cannot observe equal periods of their life-course for maltreatment victimization. Since our sample was limited to individuals registered as biological parents via birth records, we cannot determine if the parent resides with the child/ren, the amount of time spent together, or if the individual is a caregiver to any non-biological children.

We could not explore other factors impacting mental illness diagnosis that likely differ across the maltreatment groups (e.g., accessibility and utilization of healthcare services, mental health literacy, and help seeking behaviours). Children and families already involved with CPS are likely to be more visible or already connected to health services, which may influence their likelihood of receiving a mental illness diagnosis. Moreover, we recognize that multiple factors across the child, family, and environment interact to increase risk for both child maltreatment and mental illness (e.g., socioeconomic status and DFV).

Conclusions

Our findings highlight an important overlap between involvement in the child protection and mental health systems. In short, there was an increasing trend for the prevalence of diagnosed mental illness across the maltreatment groups as follows: no maltreatment < cycle breakers < cycle initiators < cycle maintainers. It is imperative that parents and children involved with the CPS have access to appropriate mental health services. Although improving in recent years, mental health interventions have typically not been parent/family-focused (Higgins et al., 2021). It is important that services provide supports (or appropriate referrals) that address the needs of individuals as parents, and the wider needs of their families. Likewise, mental health screenings during initial CPS contact as a person responsible for maltreatment are critical to provide CPS workers with a stronger understanding of how mental health needs may be impacting parenting capacity/child wellbeing, thus providing opportunities for outreach support. Given the high prevalence of diagnosed substance use disorders among individuals in our study, early intervention efforts to reduce substance use disorders in the community may also minimize the risk of child maltreatment occurring among some families. Diagnosed mental illness was substantially lower among individuals who break the cycle compared to those who maintain the cycle; perhaps some individuals are benefiting from CPS or additional therapeutic interventions or otherwise experiencing other protective/resilience factors. Future research should investigate whether interventions linked to mental health services are contributing to this outcome as well as elucidate other sources of protection/resilience.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2022). National, state and territory population. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 26/05/2022 from https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/national-state-and-territory-population/latest-release

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2012). National best practice guidelines for data linkage activities relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island people. Australian Government. Retrieved 24/05/2022 from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/indigenous-australians/national-best-practice-guidelines-for-data-linkage/contents/table-of-contents

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2020). Child protection Australia 2018–19: children in the child protection system (Child welfare series, Issue 75). Australian Government. Retrieved 17/06/2022 from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/child-protection/child-protection-australia-children-in-the-child-protection-system/contents/introduction

Ben-David, V., Jonson-Reid, M., Drake, B., & Kohl, P. L. (2015). The association between childhood maltreatment experiences and the onset of maltreatment perpetration in young adulthood controlling for proximal and distal risk factors. Child Abuse & Neglect, 46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.01.013.

Berlin, L. J., Appleyard, K., & Dodge, K. A. (2011). Intergenerational continuity in child maltreatment: Mediating mechanisms and implications for prevention. Child Development, 82(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01547.x

Capaldi, D. M., Tiberio, S. S., Pears, K. C., & Kerr, D. C. R. (2019). Intergenerational associations in physical maltreatment: Examination of mediation by delinquency and substance use, and moderated mediation by anger. Development and Psychopathology, 31. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579418001529

Chang, Z., Larsson, H., Lichtenstein, P., & Fazel, S. (2015). Psychiatric disorders and violent reoffending: a national cohort study of convicted prisoners in Sweden. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2(10). https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(15)00234-5

Chikwava, F., Cordier, R., Ferrante, A., O'Donnell, M., Speyer, R., & Parsons, L. (2021). Research using population-based administration data integrated with longitudinal data in child protection settings: A systematic review. PLoS One, 16(3). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249088

Choi, K. W., Houts, R., Arseneault, L., Pariante, C., Sikkema, K. J., & Moffitt, T. E. (2019). Maternal depression in the intergenerational transmission of childhood maltreatment and its sequelae: Testing postpartum effects in a longitudinal birth cohort. Development & Psychopathology, 31(1). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579418000032

DeLisi, M., Drury, A. J., & Elbert, M. J. (2022). The p factor, crime, and criminal justice: A criminological study of Caspi et al.’s general psychopathology general theory. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2021.101773

Dixon, L., Browne, K., & Hamilton-Giachritsis, C. (2005). Risk factors of parents abused as children: A mediational analysis of the intergenerational continuity of child maltreatment (part I). Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00339.x

Dixon, L., Browne, K., & Hamilton-Giachritsis, C. (2009). Patterns of risk and protective factors in the intergenerational cycle of maltreatment. Journal of Family Violence, 24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-008-9215-2

Doom, J. R., & Cicchetti, D. (2020). The developmental psychopathology of stress exposure in childhood. In K. L. Harkness & E. P. Hayden (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of stress and mental health (pp. 264–286). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190681777.013.12

Eastman, A. L., & Putnam-Hornstein, E. (2019). An examination of child protective service involvement among children born to mothers in foster care. Child Abuse & Neglect, 88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.11.002

Freisthler, B., Kepple, N. J., Wolf, J. P., Curry, S. R., & Gregoire, T. (2017). Substance use behaviors by parents and the decision to substantiate child physical abuse and neglect by caseworkers. Children and Youth Services Review, 79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.07.014

Gray, R. J. (1988). A class of K-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. The Annals of Statistics, 16(3). http://www.jstor.org/stable/2241622

Higgins, D., McDougall, J., Trew, S., & Suomi, A. (2021). Experiences of people with mental ill-health involved in family court or child protection processes: A rapid evidence review. Institute of Child Protection Studies, Australian Catholic University. Retrieved 15/03/2022 from https://mentalhealthcommission.gov.au/getmedia/43611e81-74a9-4e38-91e5-3c576d4f9e08/Evidence-review-Family-Law-and-Child-Protection-Stigma-and-discrimination-FINAL

Jaffee, S. R., Bowes, L., Ouellet-Morin, I., Fisher, H. L., Moffitt, T. E., Merrick, M. T., & Arseneault, L. (2013). Safe, stable, nurturing relationships break the intergenerational cycle of abuse: A prospective nationally representative cohort of children in the United Kingdom. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(4). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.04.007

Kaplan, K., Brusilovskiy, E., O'Shea, A. M., & Salzer, M. S. (2019). Child protective service disparities and serious mental illnesses: Results from a national survey. Psychiatric Services, 70(3). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201800277

Leifer, M., Kilbane, T., & Kallick, S. (2004). Vulnerability or resilience to intergenerational sexual abuse: The role of maternal factors. Child Maltreatment, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559503261181

Li, M., D'Arcy, C., & Meng, X. (2016). Maltreatment in childhood substantially increases the risk of adult depression and anxiety in prospective cohort studies: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and proportional attributable fractions. Psychological Medicine, 46(4). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715002743

Maclean, M. J., Sims, S. A., & O'Donnell, M. (2019). Role of pre-existing adversity and child maltreatment on mental health outcomes for children involved in child protection: Population-based data linkage study. BMJ Open, 9(7). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029675

Marcal, K. E. (2018). The impact of housing instability on child maltreatment: A causal investigation. Journal of Family Social Work, 21(4–5), 331–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/10522158.2018.1469563

McEwan, M., & Friedman, S. H. (2016). Violence by parents against their children: Reporting of maltreatment suspicions, child protection, and risk in mental illness. Psychiatr Clin North Am, 39(4). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2016.07.001

McKenzie, E. F., Thompson, C. M., Hurren, E., Tzoumakis, S., & Stewart, A. (2021). Who maltreats? Distinct pathways of intergenerational (dis)continuity of child maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105105

Mills, K. L., Teesson, M., Ross, J., & Peters, L. (2006). Trauma, PTSD, and substance use disorders: Findings from the Australian national survey of mental health and wellbeing. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(4). doi:https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.652

Newton, B. J. (2019). Understanding child neglect in aboriginal families and communities in the context of trauma. Child & Family Social Work, 24(2). https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12606

O'Donnell, M., Maclean, M. J., Sims, S., Morgan, V. A., Leonard, H., & Stanley, F. J. (2015). Maternal mental health and risk of child protection involvement: Mental health diagnoses associated with increased risk. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 69(12). https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2014-205240

Ogilvie, J. M., Tzoumakis, S., Allard, T., Thompson, C., Kisely, S., & Stewart, A. (2021). Prevalence of psychiatric disorders for indigenous Australians: A population-based birth cohort study. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 30. https://doi.org/10.1017/S204579602100010X

Paul, S. E., Boudreaux, M. J., Bondy, E., Tackett, J. L., Oltmanns, T. F., & Bogdan, R. (2019). The intergenerational transmission of childhood maltreatment: Nonspecificity of maltreatment type and associations with borderline personality pathology. Development and Psychopathology, 31(3). https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457941900066X

Pears, K. C., & Capaldi, D. M. (2001). Intergenerational transmission of abuse: A two-generational prospective study of an at-risk sample. Child Abuse & Neglect, 25(11). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(01)00286-1

Roscoe, J. N., Lery, B., & Thompson, D. (2021). Child safety decisions and parental mental health problems: A new analysis of mediating factors. Child Abuse & Neglect, 120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105202

Solmi, M., Radua, J., Olivola, M., Croce, E., Soardo, L., Salazar de Pablo, G., Il Shin, J., Kirkbride, J. B., Jones, P., Kim, J. H., Kim, J. Y., Carvalho, A. F., Seeman, M. V., Correll, C. U., & Fusar-Poli, P. (2022). Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: Large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Molecular Psychiatry, 27(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01161-7

Stewart, A., Ogilvie, J. M., Thompson, C., Dennison, S., Allard, T., Kisely, S., & Broidy, L. (2020). Lifetime prevalence of mental illness and incarceration: An analysis by gender and indigenous status. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 56(2). https://doi.org/10.1002/ajs4.146

St-Laurent, D., Dubois-Comtois, K., Milot, T., & Cantinotti, M. (2019). Intergenerational continuity/discontinuity of child maltreatament among low-income mother-child dyads: The roles of childhood maltreatment characteristics, maternal psychological functioning, and family ecology. Development and Psychopathology, 31. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457941800161X.

Therneau, T. (2022). A package for survival analysis in R. R package version 3.3–1. Retrieved 22/08/2022 from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survival

Thornberry, T. P., Knight, K. E., & Lovegrove, P. J. (2012). Does maltreatment beget maltreatment? A systematic review of the intergenerational literature. Trauma Violence Abuse, 13(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838012447697

Watego, C., Singh, D., & Macoun, A. (2021). Partnership for justice in health: Sco** paper on race, racism and the Australian health system. The Lowitja Institute. Retrieved 25/09/2022 from https://www.lowitja.org.au/content/Image/Lowitja_PJH_170521_D10.pdf

Whitten, T., Dean, K., Li, R., Laurens, K. R., Harris, F., Carr, V. J., & Green, M. J. (2021). Earlier contact with child protection services among children of parents with criminal convictions and mental disorders. Child Maltreatment, 26(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559520935204

World Health Organization. (2004). ICD-10: International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems: Tenth revision. World Health Organization.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the Queensland Government Statistician’s Office; Department of Children, Youth Justice and Multicultural Affairs; Queensland Registry of Births, Deaths, and Marriages; and Queensland Health. We sincerely thank the representatives from these departments for the considerable support that they provided for this project. The views expressed are not necessarily those of the departments or agencies, and any errors of omission or commission are the responsibility of the authors. The authors also gratefully acknowledge use of the services and facilities of the Griffith Criminology Institute’s Social Analytics Lab at Griffith University.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions This research was conducted with financial support from an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship awarded to EM, an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DE210100113) awarded to ST and a Griffith University Postdoctoral Research Fellowship awarded to JO. The research leading to the creation of the QCRC linked database received funding from the Australian Research Council (grant no. LP100200469).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The remaining authors declare they have no relevant financial or nonfinancial interests.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 35 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

McKenzie, E.F., Thompson, C.M., Tzoumakis, S. et al. The Overlaps between Intergenerational (Dis)Continuity of Child Protection Services Involvement and Mental Illness Diagnoses from Hospital Admissions. J Fam Viol (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-023-00610-x

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-023-00610-x